Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies vol.10 no.1 Faro jan. 2014

TOURISM - SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Influence of cultural distance on the internationalisation of Spanish hotel companies

Influencia de la distancia cultural en la internacionalización de la industria hotelera española

Germán GémarI

IUniversity of Málaga, Department of Economics and Business Administration, Campus El Ejido s/n. 29013, Málaga, Spain, ggemar@uma.es

ABSTRACT

This paper analyses a study of the influence of cultural distance on the internationalisation of Spanish hotel companies. To define cultural distance we rely on Gestelands model which allows measurement of this for each destination. Interpretation of the behaviour of people in a given country involves certain especially relevant variables. We refer to the variables deal-focus or relationship-focus cultures, formal or informal cultures, rigid-time or fluid-time cultures and expressive or reserved cultures.

As a goal, we propose to discover if these have a measurable influence, how cultural distance affects choice of a destination at which to internationalise a chain, and if countries chosen by Spanish hoteliers are more culturally compatible with Spain. The results of this study support the conclusion that cultural distance should be taken into account in studies of internationalisation of hotels.

Keywords: Cultural distance, strategic management, internationalisation, Gestelands model, country risk, hotel Industry.

RESUMEN

Plasmamos en este trabajo un estudio sobre la influencia de la distancia cultural en la internacionalización de la empresa hotelera española. Paradefinir la distancia cultural nos basamos en el modelo de Gesteland que se presenta como idóneo para medirla en cada destino. La interpretación de las conductas de las personas de un determinado país hace que determinadas variables cobren especial relevancia. Nos referimos a variables como culturas orientadas al negocio o a la relación, formales o informales, flexibles o rígidas con el tiempo y culturas expresivas o reservadas. Como objetivo, planteamos descubrir si influye y hasta qué punto lo hace la distancia cultural en la elección de un destino para internacionalizar una cadena hotelera y si los países que están eligiendo los hoteleros españoles son los más compatibles culturalmente. Los resultados de este estudio permiten, poder concluir que la distancia cultural se debe tener en cuenta en los estudios de internacionalización hotelera.

Palabras Clave: Distancia cultural, dirección estratégica, internacionalización, modelo de Gesteland, riesgo país, industria hotelera.

1. Introduction

The current economic environment experienced by companies is turbulent, dynamic and complex. Authors such as Duncam (1972), Dess and Beard (1984) and Mintzberg (1984) use different variables to explain this global market turmoil. Globalisation has clear implications for the activities of companies. An international strategy is sometimes the key to success in the market today (Pla & Leon, 2008). Jarillo (1990) emphasises that an internationalisation strategy must be taken into account when companies think about development or growth strategies.

Multinational companies perform some of their activities in different countries due to legislation differences and lower costs of production. Taking into account cultural differences between countries will make the investment decision abroad more successful (Pla & Leon, 2008).

Entering the market in other countries is conditioned by a number of variables that must be kept in mind when selecting the target country, although an adequate return on equity (ROE) is also essential to making this decision (Gémar & Jimenez, 2013).

We define cultural distance as the degree to which cultural norms in a subsidiary are different from those of its parent company (Kogut & Singh, 1988). There are some empirical studies about decisions to expand internationally using cultural distance as a variable. Drogendijk and Slangen (2006), using Holland as a reference country, analyse entry mode, creating a new company or acquiring local companies. Kim and Gray (2009), using Korea as a reference, study the way companies begin in a new country. Similar analysis has been done by Morschett, Schramm-Klein and Swoboda (2008) and López-Duarte and Vidal–Suárez (2010), with Germany and Spain as reference countries, respectively.

Through the calculation of "country risk", we can identify the risks of international businesses and investments. We have to evaluate political risks in the short, medium and long term as well as business risks in each country. This variable usually appears highly correlated with cultural distance (Harzing, 2003). Country Risk is defined through the study of the political and main economic indicators in each country.

At the same time "political diversity" and "geographical distance" usually appear to be strongly related with "cultural distance" (Dow & Karunaratna, 2006). The analysis of cultural differences between countries has been studied in business economics, so this is the key to succeed in business abroad (Pla & Leon, 2004). To calculate cultural distance, the authors focus their study on different dimensions.

Hofstede (1980) studies cultural distance in six dimensions: power distance, uncertainty avoidance, masculinity versus femininity, individualism vs. collectivism, long-term vs. short-term orientation and indulgence versus restraint. Kogut and Singh (1988) supported the work of Hofstede (1980), developing indicators to calculate cultural distance between countries. On the other hand, Schwartz (1994) distinguishes only three cultural dimensions: commitment versus autonomy, hierarchy versus equality and mastery versus harmony.

Another model is the cultural differences of Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner (1997). They identify seven dimensions: universalism versus particularism, specificity versus holism, individualism versus collectivism, interior versus exterior orientation, sequential time versus synchronous, acquired versus inherited status and equality versus hierarchy.

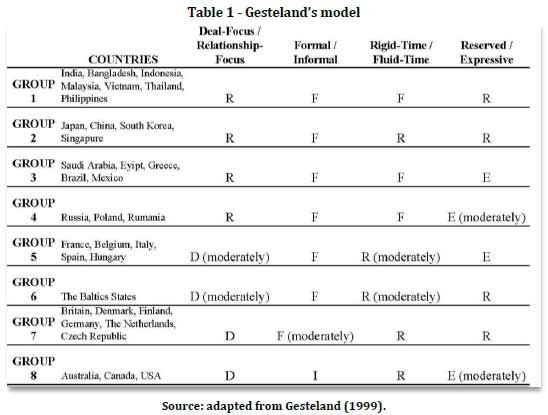

Gestelands (1999) model introduces four dimensions: deal-focus versus relationship-focus, formal versus informal cultures, rigid-time versus fluid-time cultures and expressive versus reserved cultures. Most papers use different reference countries and focus on studying the choice of entry mode (Kim & Gray, 2009; Morschett et al., 2008; López-Duarte & Vidal-Suarez, 2010).

It is important to note that there are very few studies on the intensity of the input related to cultural distance. Ng, Lee and Soltar (2007) use Australia as a reference. At the same time, there are few studies about hotels, and studies always look at entry mode using the Hofstede model to calculate cultural distance (Pla & Leon, 2001; Ramón, 2001; Furió & Alonso, 2007; Berbel-Pineda, Criado García-Legaz & Puig-Blanco, 2007). However, we seldom find studies using cultural distance as an independent variable to explain entry mode intensity. In addition, there are no empirical studies where cultural distance is measured with Gestelands model.

2. Gestelands model

Richard Gesteland (1999) is an expatriate with about 30 years of experience in understanding the behaviour of people according to the different cultures of each country. He argues that a thorough knowledge of the customs of each culture helps build success in international business.

Gesteland (1999) distinguishes two rules of international business:

The first rule is that in international business, the seller is expected to adapt to the buyer. In an international transaction, for the buyer cultural differences are less important. The buyer wants to negotiate the best deal.

If it is not a buy-sale transaction, and someone is visiting a foreign country to negotiate a joint venture or strategic alliance, rule number two comes into play. The second rule is that in international business, visitors are expected to observe local customs. This is not to merely mimic local behaviour but instead refers to being aware of local sensitivities and, in general, honouring local customs, habits and traditions.

With the information he obtained in different countries, Gesteland (1999) prepared a guide on how to understand other cultures and minimise conflicts between parties. Gesteland (1999) developed four dimensions to characterise the culture of each country:

1. Deal-Focus vs. Relationship-Focus.

2. Formal vs. Informal Cultures.

3. Rigid-Time (Monochronic) vs. Fluid-Time (Polychronic) Cultures.

4. Expressive vs. Reserved Cultures.

1. Deal-Focus vs. Relationship-Focus.

This is the main dimension according to Gesteland (1999), used to catalogue different cultures in business. Deal-focused cultures are task-oriented. For them, it is not difficult to establish contact with strangers. It is essential to express themselves clearly. Many problems are solved by phone or e- mail. Disagreements are resolved in writing. Nordic and Germanic countries, North America, Australia and New Zealand belong to this group.

On the other hand relationship-focused cultures, centre on the people with whom they are negotiating. Prior contact is preferable to do business since it is difficult to close a deal with a stranger. The language used is indirect. The Arab World, most of Africa, Latin America and Asia are examples of this group.

2. Formal vs. Informal Cultures:

For formal cultures formality in communication is a way of showing respect. Differences in position and status for people are valued. Academic degrees or doctorates are taken into account. Most of Europe and Asia, the Mediterranean Region and the Arab World and Latin America countries are examples.

In informal cultures, informal behaviour is not considered disrespectful. The United States, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Denmark, Norway and Iceland are informal cultures according Gesteland (1999).

3. Rigid-Time (monochromic business) vs. Fluid-Time (polychromic business) Cultures:

For rigid-time cultures, time schedules and punctuality are very important. Deadlines are rigid and meetings are usually not interrupted. Clear examples are Nordic and Germanic Europe, North America and Japan.

But for fluid-time cultures, people and relationships are more important than timeliness or required programming. The Arab World, most of Africa, Latin America, South and Southeast Asia belong to this group.

4. Expressive vs. Reserved Cultures:

For expressive cultures, talking loudly is normal. They often feel uncomfortable with silence. In conversation, there is little interpersonal distance and there often tends to be physical contact. People look straight in each others eyes and this is indicative of sincerity. Hands move a lot while talking. This is characteristic of the Mediterranean Region, Latin Europe and Latin America.

However, in reserved cultures people talk quietly. Some interpersonal distance should be expected. Generally continuous visual contact is avoided. Hand and arm gestures are few. East and Southeast Asia, Nordic and Germanic Europe are examples.

We summarise Gestelands model in table 1:

3. Methods

A study was performed of Spanish hotel chains with some property abroad in 2011. The data were obtained from Hosteltur (2011, 2012) and Gémar and Jiménez (2013). In 2011, there were 61 Spanish hotel chains abroad with at least one hotel. Specifically, 915 hotels and 231,738 rooms.

Those hotels located in countries not specifically mentioned in Gestelands study were removed from the sample. The sample was reduced to 49 Spanish hotel chains with hotels abroad in 2011. A total of 881 hotels with 113,056 rooms.

The objective was to analyse the intensity of the international presence of Spanish hotels and its dependence on cultural differences. A descriptive analysis of the data and some contrasts between groups was performed. Analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 15.0 (SPSS 15.0) for Windows.

The above descriptive analysis shows that 63% of hotels are implemented in countries with few cultural differences: Groups 3, 4, 5 and 6. However, Spanish hotel chains more often choose Group 3 (47% of them), especially Mexico and Brazil, as compared to Group 5 (15% of hotels), although the latter group has a zero cultural distance from Spain. Group 6 has not been chosen despite the absence of a significant cultural difference. It is important to note that while there are no significant cultural differences with Group 4, and it was expected that chains would be in place there, the reality is that only 1% of rooms are in these countries.

Note that there is great cultural distance with Group 7; however, 27% of the rooms of the hotel chains outside Spain are located in these countries, especially because of NH and Melia implementations in Germany and the United Kingdom.

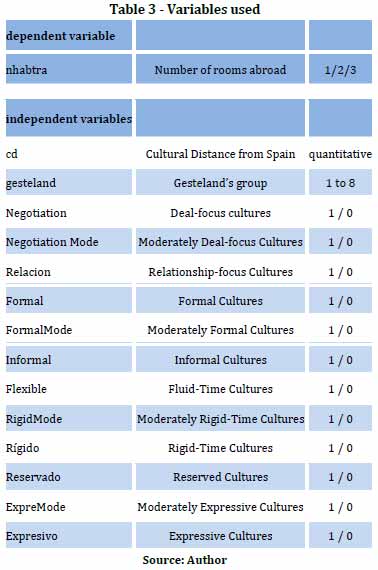

In the present study, the dependent variable (see Table 3) is the "number of rooms in Spanish hotel chains abroad in 2011" in the countries studied by Gesteland (1999). Sections of up to 100 rooms corresponds to low intensity. Between 101 and 1,500 rooms is moderate intensity and more than 1,500 rooms is considered high intensity abroad. Therefore, the nhabtra variable takes the values of 1, 2 and 3 respectively.

Each of the dimensions of Gesteland's model were considered independent variables in the first analysis. For the second analysis, the "cultural distance" variable was constructed from an evaluation of the four dimensions proposed by Gesteland (1999).

For the econometric analysis, the ordinal regression model was used to predict the value of the dependent variable and coefficients of the independent variables which best predict the value of the dependent variable were estimated. We used two ordinal regressions.

The first analysis (Model 1) was done with variables Gesteland (1999) identified as determinants of cultural distance. This ordinal regression found all coefficients of the estimated variables with high significance, which leads to the conclusion that the variables are influencing the current deployment abroad by Spanish hotel.

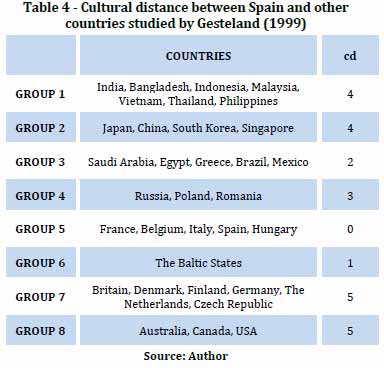

The second analysis (Model 2), was done with the variable "cultural distance" constructed according to our interpretation of Gesteland's model and the weight of each of its dimensions. This was used as a calculation method of the same weight for each dimension, except for the first (deal-focus vs. relationship-focus) because analysis of Gestelands (1999) model shows that the first dimension is the most important. The first dimension was weighted by the remaining double.

Table 4 was obtained with the cultural differences of each of the eight groups with Group 5, which is Spains group. For the countries of Spains group (Group 5), zero cultural distance was determined.

Results are shown in Table 5 for Model 1. The estimated coefficients should be interpreted as of high significance for all variables.

Adjustment of Model 2 which relates the variables cultural distance and intensity in the hotel internationalisation is presented in Table 6. Positive relationships were found for the variables deal-focus cultures, moderately deal-focus cultures, fluid-time cultures and reserved cultures.

It is noted that the most important dimensions are deal-focus and moderately deal-focus cultures. Group 5 is a moderately deal-focus culture and there is, therefore, a positive relationship. The remaining variables are significant and not necessarily indicative of a relationship with Group 5, which includes Spain.

A significant cultural distance variable appears. However, the model yields a positive relationship with a confidence interval with an opposite sign for its upper and lower limits. The results are not reliable in Model 2.

4. Conclusions

The dimensions that make up cultural distance in Gesteland's model are explanatory of hotel internationalisation. However, the existence of cultural distance does not mean that chains will not internationalise in a particular country. Cultural distance influences hotel internationalisation especially in the choice of entry mode, which was shown as significant in many studies such as Pla and León (2001), Ramón (2001), Furió and Alonso (2007), Berbel-Pineda et al. (2007), among others.

Hotel chains choose an entry mode that meets the cultural requirements of the destination country. Cultural distance should be taken into account, especially to find the best way to reach an agreement in negotiations.

The main contribution of this paper is to work with Gestelands model to measure cultural distance and not Hofstedes model, as several studies have done. It has also contributed in showing no relationship to how companies specifically seek to choose their entry mode, which has been demonstrated in many works. What was of particular interest this time was the intensity of entry.

In the internationalisation of hotel companies, it is important to note some of the dimensions of Gesteland (especially the first dimension of deal-focus) to help achieve successful negotiations. However, cultural distance is significant in the choice of entry mode but not necessarily while choosing in which country to invest.

References

Berbel-Pineda, J. M., Criado García-Legaz, F. & Puig-Blanco, F. (2007). Factores a considerar en la elección del modo de entrada para la internacionalización de la industria hotelera andaluza. Revista de Estudios Empresariales. Segunda Época, (1), 5-37. [ Links ]

Dess, G. & Beard, D.W. (1984). Dimensions of organizational task enviroments. Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 29, 52-73. [ Links ]

Dow, D. & Karunaratna, A. (2006). Developing a multidimensional instrument to measure psychic distance stimuli. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(5), 578-602. [ Links ]

Drogendijk, R. & Slangen, A. (2006). Hofstede, Schwartz, or managerial perceptions? The effects of different cultural distance measures on establishment mode choices by multinational enterprises. International Business Review, 15(4), 361-380. [ Links ]

Duncam, R. B. (1972). Characteristics of organizational environment and perceived enviromental uncertainty. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17(3), 313-327. [ Links ]

Mintzberg, H. (1984). La estructuración de las organizaciones. Barcelona: Ariel. [ Links ]

Furió Blasco, E. & Alonso Pérez, M. (2007). Las variables país e implantación exterior de la industria hotelera. Boletín económico de ICE, Información Comercial Española, (2908), 31-46. [ Links ]

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture's consequences: international differences in work-related values. Tousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (1984). Culture's consequences: International differences in work-related values (Vol. 5). Beverly Hills: sage.

Gesteland, R. R. (1999). Cross-cultural business behaviour: Marketing, negotiating and managing across cultures. Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School Press. [ Links ]

Gesteland, R. R. (2002). Cross-cultural business behavior: Marketing, negotiating, sourcing and managing across cultures. Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School Press. [ Links ]

Gesteland, R. R. (2005). Cross-cultural business behavior: negotiating, selling, sourcing and managing across cultures (pp. 320-324). Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School Press. [ Links ]

Gémar, G. & Jiménez, J. A. (2013). Retos estratégicos de la industria hotelera española del siglo xxi: horizonte 2020 en países emergentes. Tourism & Management Studies, 9(2), 13-20. [ Links ]

Harzing, A. W. (2003). The role of culture in entry-mode studies: from neglect to myopia?. Advances in international management, Vol. 15, 75-127. [ Links ]

Hosteltur (2011). Retrieved June 5, 2012 from http://www.hosteltur.com. [ Links ]

Hosteltur (2012). Retrieved June 5, 2012 from http://www.hosteltur.com. [ Links ]

Jarillo, J. C. (1990). Estrategia internacional. Madrid: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Kim, Y. & Gray, S. J. (2009). An assessment of alternative empirical measures of cultural distance: Evidence from the Republic of Korea. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 26(1), 55-74. [ Links ]

Kogut, B. & Singh, H. (1988). The effect of national culture on the choice of entry mode. Journal of international business studies, 19(3), 411-432. [ Links ]

López-Duarte, C. & Vidal-Suárez, M. M. (2010). External uncertainty and entry mode choice: Cultural distance, political risk and language diversity. International Business Review, 19(6), 575-588. [ Links ]

Morschett, D., Schramm-Klein, H. & Swoboda, B. (2008). Entry modes for manufacturers international after-sales service: analysis of transaction-specific, firm-specific and country-specific determinants. Management International Review, 48(5), 525-550. [ Links ]

Ng, S. I., Lee, J. A. & Soltar, G. N. (2007). Are Hofstedes and Scwartzs Frameworks Congruent? International Marketing Review, 24(2), 164-180. [ Links ]

Pineda, J. M. B., García-Legaz, F. C. & Blanco, F. P. (2007). Factores a considerar en la elección del modo de entrada para la internacionalización de la industria hotelera andaluza. Revista de Estudios Empresariales. Nr. 1 (2007) Segunda Época. [ Links ]

Pla Barber, J. & León Darder, F. (2002). Modos de entrada en la internacionalización de la industria hotelera española. Una aproximación empírica. Anais do XII Congreso Nacional de ACEDE, Palma de Mallorca, Espanha, 22-24.

Pla Barber, J & León Darder, F. (2004). Direccion de Empresas Internacionales. Madrid: Editorial Pearson Educacion S. A. [ Links ]

Ramón, A. (2001). Determinantes de la forma de expansión internacional. El caso de la industria hotelera española. [ Links ] IV Encuentro de Economía Aplicada, Reus (Tarragona).

Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Beyond individualism/collectivism: New cultural dimensions of values. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Trompenaars, F. & Hampden-Turner, C. (1997). Riding the waves of culture: Understanding Diversity in Global Business. Londres: N. Breadley. [ Links ]

Article history:

Submitted: 30 June 2013

Accepted: 8 November 2013