Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies vol.12 no.1 Faro mar. 2016

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2016.12103

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Hotel websites characterisation framework for consumers information needs

Referencial para a caracterização de websites de hotéis de acordo com as necessidades dos consumidores

Célia M.Q. Ramos1 , Marisol B. Correia2 , João M.F. Rodrigues3 Carlos M.R. Sousa4 ,Pedro M. Cascada5

1University of the Algarve - ESGHT and CEFAGE (University of Évora); Campus da Penha, 8005-139 Faro, Portugal. E-mail: cmramos@ualg.pt

2University of the Algarve – ESGHT and CEG-IST (Universidade de Lisboa); Campus da Penha, 8005-139 Faro, Portugal. E-mail: mcorreia@ualg.pt

3University of the Algarve - ISE, LARSyS and CIAC; Campus da Penha, 8005-139 Faro, Portugal. E-mail: jrodrig@ualg.pt

4University of the Algarve – ESGHT, Campus da Penha, 8005-139 Faro, Portugal. E-mail: cmsousa@ualg.pt

5University of the Algarve – ESGHT, Campus da Penha, 8005-139 Faro, Portugal. E-mail: pcascada@ualg.pt

ABSTRACT

Online presence is essential for tourism organisations, and the quality of websites can influence customers. In the case of hotels, there are many studies to evaluate website performance based on functionality, usability and other factors, much less on the amount of different information available to the consumer. In the near future by using Big Data it is expected that hotel websites will be dynamic, they will adapt themselves on-the-fly, showing personalized information to each consumer. Different consumers will have different websites (information available) from the same hotel. This paper presents a framework for the characterisation of hotel websites, focusing on the amount of information available to the consumer in each website, which was applied in a case study during the last months of 2013 to the websites of five-star hotels that operate in the tourist region of the Algarve, Portugal. The framework allowed to identify a set of exhaustive indicators for hotel website characterisation, which were then grouped into ten fundamental information dimensions. These dimensions further fell into four dimension groups. Finally, it is presented and discussed quantitative and qualitative evaluations, that illustrates which indicators and dimensions are more often considered on hotel websites to satisfy the consumers information needs.

Keywords: Website characterisation, tourism, hospitality, content analysis, website quality.

RESUMO

A presença online é essencial para as organizações de turismo, e a qualidade dos seus websites pode influenciar os consumidores. No caso dos hotéis, existem muitos estudos para avaliar o desempenho do website com base, entre outros fatores, nas suas funcionalidades e na usabilidade, no entanto, existem poucos sobre a quantidade de diferentes informações disponíveis para o consumidor. Num futuro próximo, através da utilização de Big Data, espera-se que os websites dos hotéis sejam dinâmicos, que se adaptem em tempo real e que apresentem informações personalizadas para cada consumidor. Este artigo apresenta um referencial para a caracterização dos websites de hotéis, com foco na quantidade de informações disponíveis para o consumidor, o qual foi aplicado num estudo de caso, durante os últimos meses de 2013, nos websites dos hotéis de cinco estrelas da região do Algarve, Portugal. A aplicação do referencial, permitiu identificar um conjunto exaustivo de indicadores para a caracterização dos websites, os quais foram agrupados em dez dimensões de informação, que por sua vez, foram agrupadas em quatro grupos. Por fim, são apresentadas e discutidas as avaliações quantitativas e qualitativas obtidas, que ilustram quais os indicadores e as dimensões mais contemplados em websites de hotéis para satisfazer as necessidades de informação do consumidor.

Palavras-chave: Caracterização do website, turismo, hotelaria, análise de conteúdos, qualidade do website.

1. Introduction

The rapid development of information and communication technologies (ICTs) over the last decades has changed the tourism and hospitality industries. ICTs have become powerful tools to help in the dissemination of tourist activities and have potentiated and increased the development of the competitiveness of all participants in these activities, from transport to accommodation, as well as catering and entertainment. An online presence is necessary for the survival and competitiveness of tourism organisations, with a more obvious impact on organisations that sell components of tourists trips, as in the case of hospitality. Among other advantages, an online presence allows the disclosure, booking and sale of accommodations through direct channels, according to customers preferences.

In this context, it is widely accepted that the Internet can serve as an effective marketing tool in tourism (Buhalis & Law, 2008). The planning and development of hotel and resort websites is increasingly pertinent, including their evaluation, to ensure that the interface with customers is as appealing and informative as possible and to transform visitors into buyers (Ramos & Perna, 2009). While developing these websites, in order to ensure that the product attains the desired quality, designers must consider usability: the website must take into consideration consumer profiles and their satisfaction when using the website (Nysveen & Lexhagen, 2001). However, these are not the only factors to take into account. One of the pioneer studies of the importance of websites to the tourism and hospitality industries was Lu and Yeungs (1998), which proposed a framework for evaluating website performance based on functionality and usability. Others, such as Chiou, Lin, and Perng (2010) recommended other dimensions, including interactivity, navigation, website marketing, place, product, price, promotion, customer relations, accessibility and speed. In 2010, Law, Qi, and Buhalis (2010) observed that the evaluation of websites is an emerging research area that has no globally accepted definition and that there is no universally accepted technique or standard for website evaluation. According to Ip, Law, and Lee (2011), studies on website evaluation fall into two categories – quantitative and qualitative – where quantitative researches usually generate performance indices to represent overall website quality, while qualitative studies assess websites quality without the use of numerical scores. More recently, new models and strategies have become available. For example, Escobar-Rodríguez and Carvajal-Trujillo (2013) presented a study identifying the strategies used by Spanish hotel websites and analysing the relationship between the size of hotels and their website strategy. Akincilar and Dagdeviren (2014) presented a multi-criteria decision-making model for evaluating hotel websites, using as case study websites of five-star hotels in Ankara, Turkey. For a complete review of the literature, see section 2 Literature Review.

Nowadays, it is already usual when any person uses e.g., Google to search something, it will appear information (publicity, etc.) related to previous searches or websites that he/she visited. By the increasing diffusion of the Big Data it is expected that hotel websites will also become dynamic, i.e., they will adapt themselves to the consumer web profile/footprint on-the-fly, showing personalized information to each consumer. Each consumer will have in the near future his or her own hotel personalized (information) website.

Based on a review of the literature (see the next section), it is possible to corroborate that there are a huge amount of studies dedicated to the evaluation of websites, but less (almost none) showing (enumerating) which is the information that could (or should) be available to the consumers. This is a very import factor, once different consumers are looking for different information or even the same information showed in a different form. As shown in the literature, and also in the present authors opinions, no consensus can be found, e.g., no agreement about the features and/or characteristics that hotel websites must have and how they should be presented, and this makes complete sense, once different consumers have different needs The only solution to this problem is to have an hotel website that adapts (semi-) automatically to each consumer.

The main contribution of the present framework to the practitioners, hoteliers, tourists and marketers managers is to sensitize these professionals to the hotel website characteristics that may be considered relevant to the needs of the five stars hotels clients. Including, what should professionals contemplate in order to meet tourists fulfilment, taking in consideration the effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction of the different information consumers (different tourists have different needs for information and different traveller goals, so the website should meet their expectations and their travellers needs).

In view of the above ideas, this paper develops a framework for the characterisation of hotel and resort websites, which was applied in a case study to the websites of five-star hotels and resorts that operate in the tourism region of the Algarve, Portugal. The framework identified a set of features permitting the characterisation and future evaluation of hotel and resort websites, in terms of the consumer search for information. The reason for using the 5-star hotels was due to be a small number of hotels, all with different characteristics, some dedicated to the general public, some to a very small niche. This will be a proof of the concept to be developed, which can later on be extended to other hotel segments.

The major contributions of this paper are: (i) the proposal, of a set of exhaustive indicators and dimensions for the characterisation of hotel websites, that meet the consumers information needs; (ii) the application of these dimensions to a specific region to obtain a regional overview; (iii) the application of the indicators to an actual tourism region (the Algarve, Portugal) and a specific set of hotels (five-star); (iv) the presentation of quantitative results and website available information quality performance and (v) the correlation of these results with guest reviews, locations and hotel size (number of rooms).

The outline of this paper is as follows. Section 2 presents the state of the art in website evaluation: indicators and dimensions that have been commonly used. The methodology used to define the framework is explained in section 3, while section 4 presents and discusses the results of the case study. Finally, in section 5, conclusions and some guidelines for future research are presented.

2.Literature review

The tourism industry has been one of the worlds largest industries to adopt the Internet as the medium for an e-business revolution (Chiou, Lin, & Perng, 2011) and provide a trustworthiness image perceived by Internet-based information (Bronner & Hoog, 2016; Gretzel, 2011;Gursoy & McCleary, 2004; Munar & Jacobsen, 2013; Pan & Li, 2011). Consequently, the relevance of websites has increased, which has encouraged the research and development of mechanisms for evaluating the performance of websites (Pan & Fesenmaier, 2006). In addition, all the content and new functionalities that have emerged on the Internet have meant that this channel is considered an excellent marketing tool for the tourism industry (Law et al., 2010). According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS, 2006), website evaluation can be defined as the act of determining a correct and comprehensive set of user requirements, ensuring that websites provide useful content that meets users expectations and setting usability goals (Law et al., 2010). This conceptualisation is, in reality, not new. The World Tourism Organisation (WTO) (WTO, 2001) has developed a set of practices for the development of websites in tourism organisations, taking into account the role they intend these websites to play within their marketing strategies, in order to increase demand, sales and revenue; reduce costs and response time and improve communications and customer relationships.

This section does not seek to survey all the studies and models about the analysis, evaluation, performance, usability and importance of websites for hotels. It focuses only on the twenty most relevant researches that have contributed directly to the present study. Chung and Law (2003) developed a conceptual framework to measure the performance of hotel websites, which consisted of five major hotel website dimensions, whose levels of importance were evaluated by hotel managers. Their findings showed significant differences in performance scores for all dimensions among luxurious, mid-priced and low-budget Hong Kong hotel websites. Morrison, Taylor, and Douglas (2004) proposed a modified balanced scorecard method for tourism and hospitality website evaluation and predicted that a benchmarking approach, which combines user perceptions with website performance, would become an important approach in research in this area. Later, Baloglu and Peckan (2006) classified website design characteristics into four categories, applying these to four- and five-star hotels in Turkey. Their results showed that, the hotels were not using the Internet to its full potential and had not effectively applied e-marketing in their hotels.

In addition, Zafiropoulos and Vrana (2006) proposed an evaluation framework for hotel websites that categorises web information services into six dimensions by applying hierarchical cluster analysis. They used this to compare the performance of the top 25 hotel websites in Greece. In 2008, Maswera, Dawson, and Edwards (2008) carried out two surveys. The first consisted of an analysis of the nature and extent of e-commerce adoption by tourism organisations in four countries of sub-Saharan Africa. In the second, in the U.S. and Western Europe. These authors presented an exhaustive list of characteristics of e-commerce websites, as well as a descriptive analysis of the data collected. Later, in 2009 (Maswera, Dawson, & Edwards, 2009), explained how tourism organisations from the sub-Saharan African countries studied could develop their websites into marketing tools and how they could overcome impediments to e-commerce adoption and usage.

Using structural equation modelling, Schmidt, Cantallops, and Santos (2008) investigated the characteristics of hotel websites and their implications for website effectiveness. The authors suggested that there is a circular effect between website characteristics and consumer demand, as it appears that hotel websites respond inefficiently to consumer demand for commercial transactions, which encourages consumers to use traditional tourist distributors. Kim and Fesenmaier (2008) analysed the key elements in information on first impressions of tourism destination websites. Their results confirmed that, at that time, the majority of state tourism websites in the U.S. met the basic needs of travel information seekers in terms of the characteristics of format and usability, but that other design characteristics, such as credibility, inspiration, involvement and reciprocity-related design elements, were not perceived as favourably. Hernandéz, Jiménez, and Martín (2009) defined accessibility, speed, navigability, content quality and a web assessment index as the features that should be studied in website quality evaluation. The authors concluded that hotels internet popularity and their position in search engines facilitate their entry into inaccessible markets.

According to Law, Leung, and Buhalis (2009), good web design goes beyond technology, design and layout. In 2010, the same authors (Law et al., 2010) analysed 75 published articles considered relevant to the hospitality and tourism industries, categorising the articles based on industry sectors, regions and evaluation approaches. The results showed that hotel, restaurant and lodging websites are the most popular focus, followed by destination and travel websites. In addition, Chiou et al. (2010) analysed 83 studies and concluded that website evaluation has been studied using three approaches. (a) The information systems (IS) approach includes over 75% of technology-oriented factors, such as usability, accessibility, navigability or information quality, while (b) the marketing factor includes over 75% of marketing related factors, such as advertising, promotion, online transaction, order confirmation or customer service. (c) The combined framework is defined as using a mixture of IS and marketing factors. The authors found a pattern showing that the majority of web evaluation studies used an IS-approach before 2001, and, since then, the combined approach has emerged as dominant. They used a 53 criteria pool for website evaluation categorised into five marketing oriented factors – product, promotion, price, place and customer relationship – 4PsC factors slightly modified from the marketspace model of Dutta and Biren (2001), to which was added the customer relationship management (CRM) factor.

Ip et al. (2011) reviewed 68 website evaluation studies and introduced a definition of ranking. The same authors suggested (Ip, Law, & Lee, 2012) that, as human judgement is often uncertain and vague, the use of a fuzzy set theory approach enables evaluators to capture decision-makers uncertainty. Their results indicated that reservation information is the most important criterion for website functionality. Line and Runyan (2012) reviewed hospitality marketing research published in four top hospitality journals from 2008 to 2010 and concluded that, at that time, more marketing researches were needed on social media and about Web 2.0 in the tourism sector. Qi, Law, and Buhalis (2013) applied a fuzzy model to assessing the performance of hotel websites, and their results indicated that functionality and usability dimensions are equally important. Pengnate and Antonenko (2013) showed that an important topic in the field of website evaluation is the analysis of the impact of emotional design levels and metacognitive awareness of website trustworthiness.

Suárez-Torrente, Martínez-Prieto, Alvarez-Gutiérrez, and Alva de Sagastegui (2013) believe that there is much literature on heuristic evaluation by experts on websites usability, but there is a lack of clear and specific guidelines to be used in the development and evaluation process. In this context, they presented Sirius, a heuristic-based usability evaluation framework for expert evaluation that takes into account different types of websites. In contrast, Escobar-Rodríguez and Carvajal-Trujillo (2013) found that the websites of many hotels are starting to incorporate new online tools, such as social media, in order to maintain closer relationships with customers and investors. Díaz and Koutra (2013) evaluated persuasive features of hotel chains websites. They separated hotel chains into categories and then proceeded to segment hotel chains into types according to the persuasiveness of their websites, using latent class segmentation. Akincilar and Dagdeviren (2014) presented a hybrid multi-criteria decision-making model for evaluating hotel websites, using as a case study websites of five-star hotels in Ankara, Turkey. Correia, Ramos, Rodrigues, and Cardoso (2014) presented a framework which allowed to identify a set of comprehensive indicators and dimensions that can be quantified and analysed in terms of quantitative and qualitative results.

More recently, Hao, Yu, Law and Fong (2015) proposed a Genetic Algorithm based learning approach to investigate the customer satisfaction associated to the evaluation of OTA websites. Salavati and Hashim (2015) used the content analysis technique and identified 48 different features of the websites of 75 Iranian hotels and concluded that the results indicate that page ranking and the hotel star rating are significantly related to website performance. Bronner and Hoog (2016) analysed the role of web-based information in tourism measure one-time interactions throught a longitudinal study.

As an initial conclusion, there are several criteria, frameworks, tools and techniques for website evaluation, but there is still no agreement about the features and/or characteristics that hotel websites must have and how these should be presented in terms of consumer satisfaction when searching for information in the website (Salavati & Hashim, 2015). The evaluation of websites is needed to facilitate continuous improvements, as well as to analyse the website performance of competitors and track the performance of their websites over time (Morrison et al., 2004), but this doesnt mean that the consumers are satisfied with the information presented. In the literature there aren´t guidelines for the development of hotel websites or for the information that a consumer expected to see in the website. This is only possible by analysing the content available (in all hotel websites), feeding only the information to each website (webpage) that each specific user web profile requires.

3. Methodology

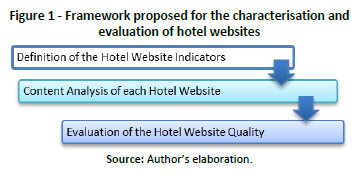

The proposed framework was structured in three phases. The first, (a) comprised the definition of the indicators and dimensions of hotel websites (Akincilar & Dagdeviren, 2014; Diaz & Koutra, 2013). The second (b) consisted of the content analysis technique to evaluate the presence of indicators on the hotels websites (Salavati & Hashim, 2015). Finally, the third (c) consisted of relevant techniques to measure, characterise, analyse and evaluate the hotel websites quality (Calero, Ruiz, & Piattini, 2005; Wang, Law, Guillet, Hung, & Fong, 2015) (see Fig. 1).

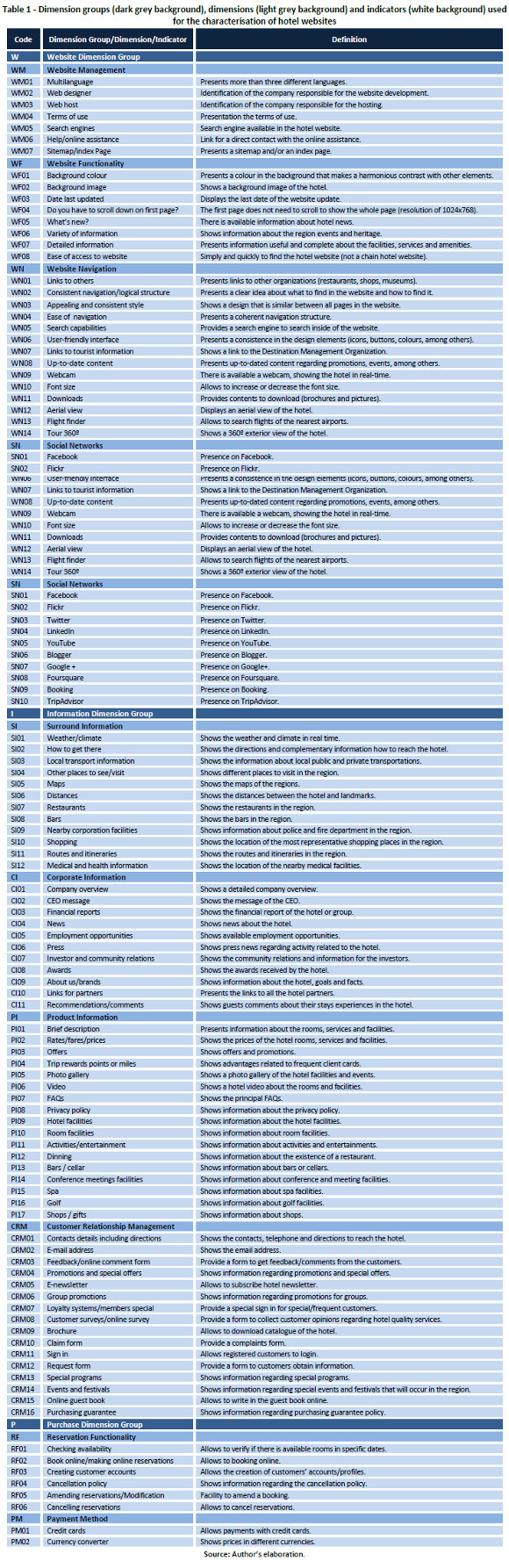

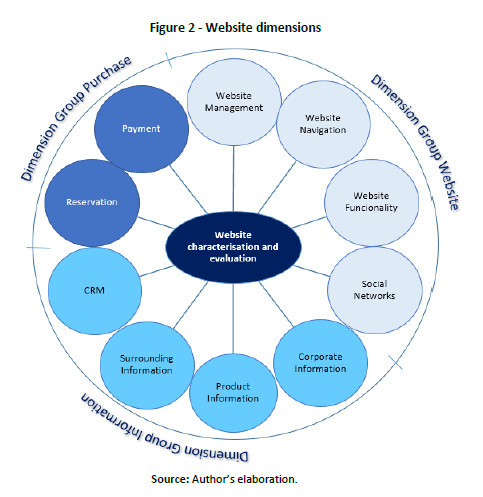

The definition of hotel website indicators and dimensions involved in identifying features and characteristics of hotel websites, designated as indicators. With these indicators defined, the next step consisted of grouping them into dimensions. Each dimension comprises a group of indicators with the same purpose/goal/function. This step also included the formation of dimension groups that integrate related dimensions.

The indicators, dimensions and dimension groups were based on the literature and complemented with an empirically derived inventory. In the case of the indicators, new ones were introduced that had emerged from the evolution of ICT and used in new ways to show activities, amenities and other aspects. The indicators were inventoried by analysing which new characteristics/features appeared on at least two websites of hotels within the five-star segment covered in this study. There were several studies from the literature (see section 2) used to define the indicators and dimensions: those eight were listed. These contributed with the most indicators; nevertheless, others indicators were extracted from other authors (Li, Wang, & Yu, 2015; Ting, Wang, Bau, & Chiang, 2013; Wang et al., 2015).

The list below only presents the dimensions proposed by the below authors (authors: dimensions), including the indicators they propose (along with others) integrated with empirical contributions and shown in Table 1. The reason to choose the (below) authors are due to be the authors/papers with a high number of citations, as well as to be the authors/papers well recognized by the peers. The detailed explanation why each of the following authors choose each indicator is out of the focus of the paper, please report to the original authors paper:

(a) Chung and Law (2003): facilities information, customer contact information, reservation information, surrounding area information and management of website;

(b) Baloglu and Peckan (2006): interactivity, navigation, functionality and website marketing features;

(c) Zafiropoulos and Vrana (2006): information facilities, guest contact information, reservation/price information, surrounding area information, management of the website and company profile;

(d) Maswera, Dawson, and Edwards (2006, 2008): corporate information, product information, non-product information, CRM, reservations and payment;

(e) Schmidt et al. (2008): promotion, price, product, multimedia, navigability, reservation system, security and customer retention and privacy;

(f) Hernandéz et al. (2009): accessibility, speed, navigability and content quality;

(g) Chiou et al. (2010): place, playfulness, product, price, promotion and customer relations.

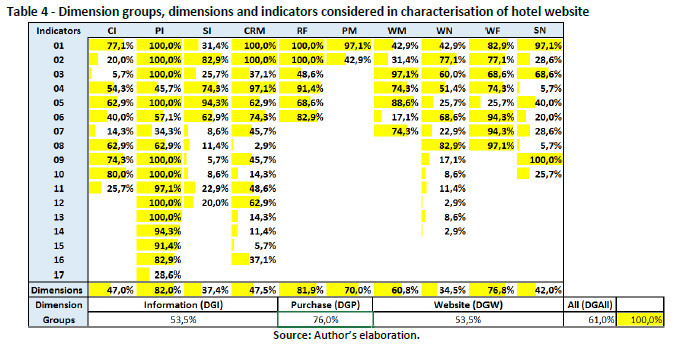

As mentioned, Table 1 enumerates all the indicators collected from the literature and from the empirical compilation. In addition, as shown on the lighter grey background, the dimensions are distilled down to ten (see also Fig. 2): (i) website management, (ii) website navigation, (iii) website functionality, (iv) social networks, (v) surrounding information, (vi) product information, (vii) corporate information, (viii) CRM, (ix) reservations and (x) payment. Table 1 also shows, on dark grey, the four dimension groups (Fig. 2, outside ring), which integrate the above dimensions that are related. (a) Dimension group website (DGW) combines dimensions i–iv. (b) Dimension group information (DGI) combines dimensions v–viii. (c) Dimension group purchase (DGP) combines dimensions ix–x, while (d) dimension group all (DGAll) combines all the dimensions (i–x).

The next step, in the framework proposed for the characterisation and evaluation of hotel websites, was the observation and collection of hotel website indicators, by the method of user judgement which is the second most used in accordance with the working of Law et al. (2010) and accordingly with Jeong and Lambert (2001) the assessment of hotel website involves perception of the user. As already mentioned, this study focuses on five-star hotels and resorts websites, using as a case study the tourism region of the Algarve, Portugal, and only on hotels with an online presence on the Booking.com website (for detailed characterisation of the region see section 4). The reason for this is that this study is only concerned with hotels that are on some level interested in being represented on the Internet and appear on this world leader in booking accommodations online. Of hotels and resorts meeting those conditions, 35 hotels were analysed, from the 38 that could be found for this region.

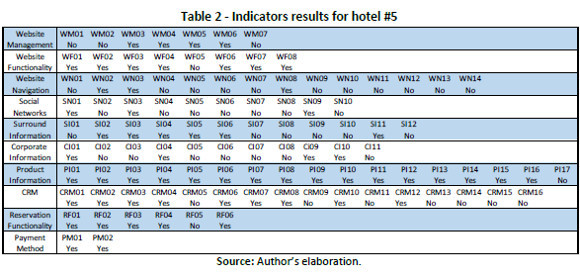

Taking as a starting point the entries for these hotels on Booking.com, the links to the respective websites were gathered, and the websites were analysed in terms of the indicators proposed in Table 1. In addition, in order to minimise subjectivity, all the indicators proposed were considered binary (i.e. corresponding to yes/no) (Diaz and Koutra, 2013; Neuendorf, 2002), which consisted of the presence or absence of a specific indicator. All the indicators were gathered by five different people, and all had to agree on the same classification (yes or no). These types of binary variables/indicators also avoid the need for Likert scales with many levels, which can insert a high level of subjectivity (Morrison et al., 2004). As an example, Table 2 shows the application of indicators to a hotel with the best scores on Booking.com and TripAdvisor.com referenced with the number 5. This hotel is located around 20 km from the centre of the region (Faro) and about the same distance from the local international airport.

In the last step, characterisation of the hotel websites, two strategies were used: (i) the characterisation of the regions hotel websites and (ii) the characterisation of specific hotels. For the first case, characterisation of the regions hotel:

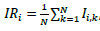

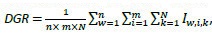

I. A frequency table of the indicators for the region IR were computed by averaging the same indicator from all the hotels within the study region. Each indicator I (with a response of yes = 1 and no = 0) was defined as Ii,k={WMi,k,WFi,k, SNi,k, SLi,k, PLi,k, CLi,k, CRMi,k, RFi,k, PMi,k }, with k = {1,

, 35} as the hotel reference number; i = {{1,

,mWM}, {1,

,mWF }, {1,

,mWN }, {1,

,mSN }, {1,

,mSI }, {1,

,mPI }, {1,

,mCI }, {1,

,mWCRM }, {1,

,mRF } and {1,

, }} as the index of each indicator and m number of indicators within each dimension, respectively: mWM = 7, mWF = 8, mWN = 14, mSN = 10, mSI= 12, mPI = 17, mCI = 11, mCRM = 16, mRF = 6 and mPM = 2. Therefore, , where N is the number of hotels in the study (see Table 4, rows 2–18, indicators 1–17).

, where N is the number of hotels in the study (see Table 4, rows 2–18, indicators 1–17).

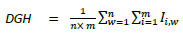

II. The dimensions within the region DR = {WM, WN, WF, SN, SI, PI, CI, CRM, RF, PM} were computed by the average of all the indicators from all hotels within the same dimension:  (see Table 4, row 19).

(see Table 4, row 19).

III. For the dimension groups DGR = {W, I, P, All}, the averages of the indicators for all hotels within the same dimension and within the group in question were computed (i.e.  , with n = 4 for the website and information DG, n = 2 for purchase DG and n = 10 for the computation of all indicators (and dimensions)) (see Table 4, last row).

, with n = 4 for the website and information DG, n = 2 for purchase DG and n = 10 for the computation of all indicators (and dimensions)) (see Table 4, last row).

In the case of the characterisation of specific hotels, our approach propose the following steps:

I. The website binary indicator = {WMi,WFi, SNi, SLi, PLi, CLi, CRMi, RFi, PMi}

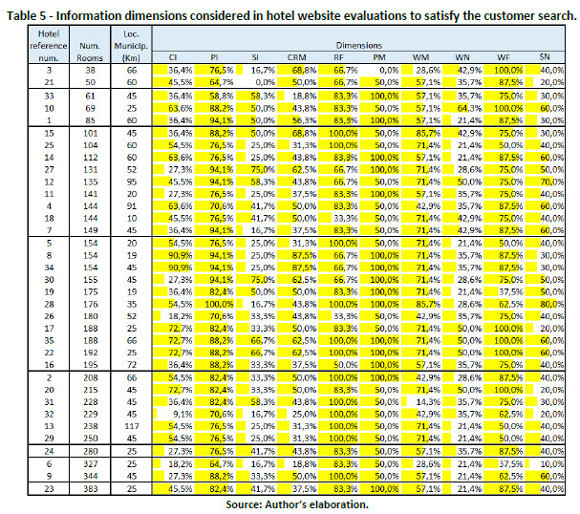

II. The dimension within the hotel DH, using the same dimensions but now  (see Table 5, columns 4–13)

(see Table 5, columns 4–13)

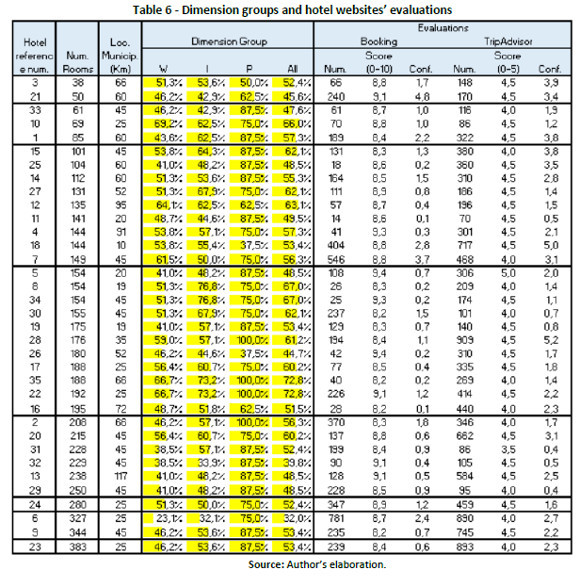

III. For the dimensions group within the hotel DGH, using the same dimension groups but now  (see Table 6, columns 4–7)

(see Table 6, columns 4–7)

IV. If at least half of the dimensions or group of dimensions showed a contribution of negative values (=50%) (see Table 5, columns 4–13 and Table 6, columns 4–7)

V. If at least half of the dimensions or group of dimensions showed a positive contribution higher than 65% (see Table 5, columns 4–13 and Table 6, columns 4–7)

The evaluation consisted, in both cases (i–ii) from steps I–III, in analyses of percentages returned from the results of each indicator, dimension and dimension group. In the case of IV and V, the output was only yes (which does occur) or nothing otherwise. In addition, qualitative words were considered to analyse the results, taking into consideration percentage intervals. These words are considered to represent the amount of information available to the consumer in each of the hotel websites, it doesnt qualify the quality of the information neither of the website, only the amount of different information available. The concern for satisfying the user for information, both in terms of technologies and in terms of information systems, has been the subject of research over the years, taking as an example the work done by Chikara and Takahashi (1997), Darmawan (2005) and Yu, Park, Kim, Lee, and Yoon (2014). Considering a percentage scale, as a result, it was easier to extract some knowledge from the results: poor [0%, 50%]; fair [50%, 65%]; good [65%, 90%] and excellent [90%, 100%].

4. Results and discussion

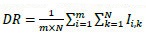

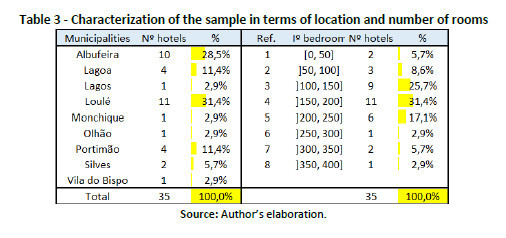

The study population was composed of five-star hotels in the Algarve, a region in the south of Portugal with 5,412 km² and around 450,000 habitants (http://www.visitalgarve.pt/). The study was conducted in the last months of 2013, so the sample corresponded to the 35 five-star hotels with an online presence on Booking.com during that period. To better characterise the population under analysis, the hotels were also studied in terms of the number of rooms and location. Table 3 presents the percentage of hotels in the study by their number of rooms. As can be seen, the majority of the hotels have between 150 and 200 rooms, and more than 74% have between 100 and 250 rooms. In term of location (see also Table 3), most of the hotels are located in Albufeira (28.5%) and Loulé (31.4%), for a total of 60.0%. These hotels are located more or less in the centre of the Algarve, at the most 40 km from the international airport of Faro, with access to the highway no more than 10 minutes away.

Table 4 shows the results for the regional hotel websites analysis, with each indicator expressed in the first column and the respective indexes in rows 2–18. It also shows the results for the 10 dimensions in the row 19 and dimension groups in the last row.

In terms of indicators and dimension analysis and evaluation, in the:

(a) Website managementdimension(WM) (60.8%):There was no predefined/standard number of languages used per website/hotel. Hotels fluctuated from 1 language (11.4%) to 10 different languages (2.9%). We defined multi-language hotels as those with at least 4 different languages available on their website, and almost half (42.9%) met that definition. It was observed that only a few websites named the web designer (31.4%), and almost all the websites showed the web host (97.1%). It needs to be noted that the majority of the websites showed terms of use (74.3%), search engines (88.6%) or sitemaps (74.3%). Only a few websites had online assistance (17.1%).

(b) Website navigationdimension (WN)(34.5%): Only a few websites presented links to others (42.9%) or the tourism information office (22.9%), but almost all the hotels presented the information as updated (82.9%). In generally, the majority (77.1%) of the websites had a consistent navigation/logical structure, 51.4% of the websites had intuitive navigation and 68.6% of the websites presented a friendly interface, from which can be concluded that there was still much work to be done in this area. In this dimension also were considered features associated with new technological applications and innovative characteristics that were present on some websites, such as to watch images from the hotel using a webcam (17.1%), change the font size (8.6%), download brochures or information about the hotel (11.4%), view pictures that show the hotel in an aerial view (2.9%), find a flight when travellers need to know something about their plane departures and arrivals (8.6%) and take a 360º tour of the hotel (2.9%).

(c) Website functionalitydimension (WF)(76.8%): Almost all the websites presented problems in this category, since a few did not have a background colour (17.1%) or a background image (22.9%) and also, in some of them, the user could not scroll down the first page when using a resolution of 1024×768 (25.7%). Only 25.7% presented the feature Whats new?, which represented an extremely low percentage. This feature can lead to an increase in the frequency of views of the websites or to further consultations of the news that the websites offer tourists.

(d) Social networksdimension (SN)(42.0%): All the hotels already had an online presence. The social network included the most was Facebook (97.1%), followed by Twitter (68.6%). However, there were social networks that were not included by many hoteliers, as in the case of LinkedIn (5.7%) and Foursquare (5.7%). Flickr (28.6%), Google+ (28.6%), Blogger (20.0%) and TripAdvisor (25.7%) despite being included on some hotel websites still had a quite low percentage of importance attributed to them by consumers when choosing the characteristics of their intended vacation destinations.

(e) Corporate informationdimension (CI)(47.0%): This includes several features about the organisation. Only 5.7% of the hotels presented financial reports, 14.3% showed investor and community relations and 20.0% had a message from the CEO. All these numbers were lower than expected. Most of the hoteliers were aware of the presentation of online information about their company (77.1%), as well as the transparency of their brand (74.3%) and connections with other partners (80.0%).

(f) Product information dimension(PI)(82.0%): There were some features considered by all (100%) hotels in the study, such as a brief description, prices, offers, a photo gallery, hotel facilities, room facilities, dining facilities and bars. On the other hand, there were features not yet considered by the majority of them, such as trip or mileage reward points (45.7%), FAQs (34.3%) and information about shops and gifts (28.6%).

(g) Surrounding informationdimension(SI)(37.4%): There were already many websites that displayed maps (94.3%) and presented information on how to get there (82.9%). However, many did not disseminate enough information about the weather (31.4%), local transportation information (25.7%), restaurants in the surrounding area (8.6%), bars (11.4%), shopping (8.6%), nearby corporate facilities (5.7%), routes and itineraries in the region (22.9%) or medical and health information (20.0%).

(h) Customer relationship managementdimension(CRM) (47.5%): This includes the features that encourage relationships to develop with customers, which can enhance and strengthen relationships with hotels in order to maximise customers loyalty – of relevance because it is more expensive to attract new customers than to keep existing ones. All hotels in the study presented an email address and contact details, including directions. These features are extremely relevant because they establish communication channels between clients and the hotels and show that the hotels are located in a particular place – no longer an abstraction but something concrete. In terms of processes and concerns about customer loyalty, there was still much to do. In this dimension, the majority of websites presented promotions and special offers (97.1%), group promotions (74.3%), newsletters (62.9%) and request forms (62.9%). On the other hand, there are special features that can be included in hotel websites, including, among others, customer online surveys (2.9%), to understand if customers are satisfied with the service; online guest books (5.7%), to enhance customers experience and feedback; events and festivals calendars (11.4%), to show the existence of events in proximity to the hotels, to encourage customers to choose one hotel over another hotel nearby; belonging to the same competitive set – complaint forms (14.3%), to get the opinion of clients and detect where service can be improved and special programmes (14.3%), to encourage website visitors to become future clients.

(i) Reservation functionalitydimension(RF)(81.9%): In this group, 48.6% offered the opportunity to create customer accounts, followed by the chance to amend and modify reservations (68.6%). There were still a small percentage of websites that lacked cancellation policies (8.6%) or the ability to cancel online (17.1%). This does not help to create an image of the safety and transparency of information about the hotels.

(j) Payment method dimension(PM)(70.0%): Only 2.9% did not refer to the possibility of using a credit card and only 42.9% showed a currency converter.

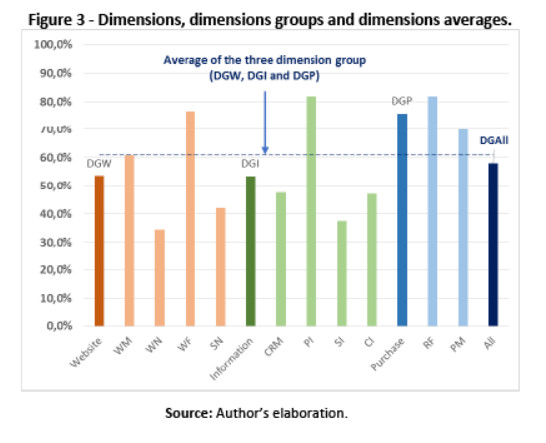

Fig. 3 presents the results of the four dimension groups (DG) with the respective associated dimensions. It can be seen that overall the four DG presented positive values. Nevertheless, DGW barely achieved a classification of fair (53.5%), in our evaluation of information available, which indicates that more work should be done in this area to improve the websites. DGI was also fair, with similar results (53.5%), which indicates the hotels need to improve their information output, to satisfy the customer information search. Finally, DGP achieved a classification of good (76%), in our evaluation rating scale. This was the aspect that presented the best results, but, overall, it was easy to discover where these hotels need to make changes to their websites, to increase customer satisfaction for information.

For a more global overview, the average of all the dimensions (DGAll), as shown in Figure 3, was calculated, returning as fair (58.0%), which was, in fact, a value lower than expected. One reason (perhaps not quite consistent) could be that these hotels are five-star, so their websites are not the most important way to market the hotels and to disseminate information about their hotel. However, most probably, the reason is that the CEOs of these hotels are not aware of all the dimensions and indicators that hotel websites should have. There are also additional interesting qualitative output, for instance, the surrounding information, where the social network indicator also presents values much lower than expected (varying between poor and fair), in the evaluation about the amount of information available in a hotel website. On the other hand, product information, website functionality and reservations presented unexpectedly good values. It is quite interesting that no dimension had excellent, although of the 103 indicators, 25 had excellent, a number above that expected.

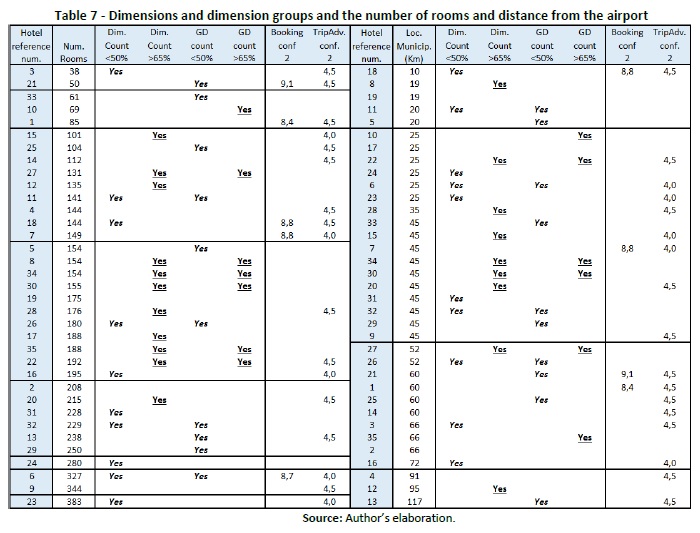

Table 5 shows the results of the dimensions and dimension groups per hotel and also the number of rooms and approximate distance (in km) from the hotels to the capital of the region (or to the international airport, which is situated extremely nearby, less than 10 km from the centre of the regions capital). The same table also shows evaluations on Booking.com and TripAdvisor.com, at the time of the study, for each hotel with the respective number of evaluations. For these evaluations, a quite simple confidence ratio was created, , with the number of evaluations and the number of rooms in each hotel.

Looking at the values in Table 5 and Table 6, it can be seen that:

(a) Only a few dimensions were more or less uniform for all the hotels (e.g. PI and WF), which shows that many of the hoteliers are not aware of all the dimensions that should be presented on websites. Looking at DG, only purchase presented some excellent results. The other two, website and information, varied from poor to fair; nevertheless, the information dimensions presented better results.

(b) In addition, it is quite interesting to note that only two hotels (#22 and #35) had values above 70%, and these were not the hotels with the best evaluations on Booking.com and TripAdvisor.com. The hotel with the best results on Booking.com and TripAdvisor.com was hotel #5, which in our study overall had a classification of poor (48.5%). Looking at these results and after having made several correlation attempts, it was obvious for the authors that the 10 dimensions and the four dimension groups analysed do not have any significant relationship with the hotels final classifications, when compared with the results of evaluations on Booking.com and TripAdvisor.com.

(c) Even more interesting is Table 7 that shows results in terms of bedrooms per hotel. The hotels that had better evaluations (yes underlined) on the websites (i.e. good) were the ones that had a number of rooms between 150 and 200, followed by the ones that had between 100 and 150 rooms. Despite being difficult to analyse, the worst results of poor (yes in italics) appear for hotels with 200 and 350 rooms per hotel.

(d) In terms of distance to the international airport or to the capital of the region, the hotels that presented better results were the ones with distances between 25 and 50 Kms from the international airport.

(e) Using again Table 7, another analysis was also done, which consisted of removing all the Booking.com and TripAdvisor.com evaluations with a confidence ratio above two. Only two hotels (#22 and #28) that had good evaluations in this study were evaluated by Booking.com and TripAdvisor.com. Once again, it appears at this level of hotels, websites are not the most important tool used to communicate with clients and to disseminate the information to satisfy the users search for information. In addition, combining Table 5, 6 and 7 and the indicators, all the hotels in this group have the most essential characteristics on their websites.

5. Conclusion

We developed a framework for the characterisation of hotel and resort websites that can be applied to different regions and different hotel classifications, taking in consideration the amount of information available to the customer. In our study, it was applied to five-star hotels websites in the Algarve region of Portugal. The framework here presented allows the identification of a set of comprehensive indicators, information dimensions and information DG that can be used by hotels decision makers to quantify and evaluate their hotel websites, in terms of satisfying the consumer needs for hotel information, with results that can be analysed in terms of quantitative and qualitative values. From our study, it is possible to conclude that the hotels studied pay more attention to dimensions such as website functionality, reservations and product information, which, in our opinion, can be explained by hoteliers needing to present, publicise and sell their rooms. To meet this need, hoteliers have to publicise information about the qualities of their rooms and services on websites characterised by adequate functionality. In addition, it is important to present a mechanism that allows consumers to conclude their purchase or make reservations. In these situations, the characteristics associated with the purchase dimension can make the difference if customers have sufficient, transparent information about how to make reservations.

There are even more dimensions that are neglected, including website navigation, social networks, corporate information and CRM. Website navigation is a quite important dimension to analyse. If customers feel too confused to achieve their goals (e.g. to understand how can make a reservation), they will abandon the hotels websites and go to others or try a different way to make reservations. The social networks dimension is quite new, and some decision makers are not aware of the need to include these features on their websites, as a way to manage their online reputation, or their focus strategies havent a relationship with the website information performance.

Overall, this study supports the conclusion that, for the websites analysed, five-star hotels, owners and CEOs are not alert to all-important indicators and, consequently, to information dimensions relevant to their hotels websites, since only two hotels cover more than 72.8% of the indicators considered in this studys framework. Once again, the reason that could explain why only two hotels achieved this maximum is that hotel websites for five-star hotels are not the most import channels to their customers.

In this study, the investigation was extremely exhaustive in the identification of indicators that can be considered while characterising hotel websites in terms of consumer satisfaction regarding hotel information, and, for this reason, the authors did not expect many hotels with a rating of excellent. Nevertheless, some were expected to achieve that ranking, which did not occur. Only five hotels achieved a good classification and ten achieved only poor. This result was much lower than expected because in our days the customer searches for huge amount of variety of information in hotel websites and it is believed that websites should reflect this trend.

The advantages of this framework and study are that researchers and web developers now have a tool that can exhaustively characterise the information that hotel websites can present, which can be used in different regions around the globe. With the website indicators framework presented in this study, websites characteristics can be quantified without subjectivity, and hoteliers can easily make conclusions about their own websites. With the clear enumeration of indicators in Table 2, it is now also possible for software engineers in charge of website development to design more dynamic (in function of the user web profiles) and informative websites, which can be considered an additional channel to increase the online reputations of hotels.

In term of comparison with other studies, the biggest contradiction in results was with Schmidt et al. (2008), who suggested that there is a circular effect between website characteristics and consumer demand, as it appears that hotel websites respond inefficiently to the consumer demand for commercial transactions, which encourages consumers to use traditional tourist distributors. They argued that hotel revenues continue to originate from tourism operators and travel agencies, reducing hoteliers interest in developing effective website reservation systems. In the present study, the results contradicted this as the websites of five-star hotels and resorts in the Algarve analysed have reservation systems – some owner-generated, others developed by third parties – that allow customers to check availability and book online.

This study still presents some limitations, once should include an interview with the hotel managers for clarifying the relationship between their strategies, website business models and website performance, and should be complemented with eye tracking technics to analyse the website usability in order to find possible design problems. Finally, it only focus in 5 star hotels on a single region.

For future research, our results suggest: (a) applying this framework to the same group of hotels in other regions to analyse differences and to see if there are differences in websites that depend on technological and social-economic realities of regions, (b) correlating the information presented on websites with the number of bookings in hotels, (c) applying the framework to different groups of hotels in the region: lower rating hotels (four- and three-star, or others) and other kind of accommodations (B&B, among others), (d) interviewing the hotel managers and the website consumers to analyse the relationship between their strategies, website business models and website information performance in order to adjust our indicators and information dimensions to their answers, (e) including eye-tracking technology to analyse websites, thereby creating another dimension and comparing results and (f) taking care with accessibility rules when developing websites, forming yet another dimension and combining all values to reach conclusions about new trends – if they change the results or have other impacts.

Currently, most travellers searching for rooms and analysing corresponding hotel websites may abandon these if they show poor information, unattractive, or not focused to their personal preferences. In these situations, customers will try to find another hotel with their pretended information. In the near future, it is expected that hotel websites adapt to the personal characteristics of each consumer by using the web profile of the consumer. This study will help to describe and characterise all (present) features and dimensions available in the hotel websites, in which the researches, hoteliers (and web developers) can support to develop dynamic websites, which adapts on-the-fly to each consumer.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by FCT project PEst-OE/EEI/LA0009/2013; FCT and FEDER/COMPETE under Grant PEst-C/EGE/UI4007/2013.

References

Akincilar, A., & Dagdeviren, M. (2014). A hybrid multi-criteria decision making model to evaluate hotel websites. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 36, 263-271. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.10.002. [ Links ]

Baloglu, S., & Peckan, Y. (2006). The web design and Internet website marketing practices of upscale and luxuary hotels in Turkey. Tourism Management, 27(1), 171-176. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2004.07.003. [ Links ]

Bronner, F., & Hoog, B. (2016). Travel websites: Changing visits, evaluations and posts. Annals of Tourism Research, 57, 94–112. Doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2015.12.012. [ Links ]

Buhalis, D., & Law, R. (2008). Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 year on and 10 years after the internet: the state of eTourism research. Tourism Management, 29(4), 609–623. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2008.01.005. [ Links ]

Calero, C., Ruiz, J., & Piattini, M. (2005). Classifying web metrics using the web quality model. Online Information Review, 29(3), 227-248. Doi: 10.1108/14684520510607560. [ Links ]

Chikara, T., & Takahashi, T. (1997). Research of measuring the customer satisfaction for information systems. Computers & industrial engineering, 33(3), 639-642. doi:10.1016/S0360-8352(97)00211-8. [ Links ]

Chiou, W., Lin, C., & Perng, C. (2010). A strategic framework for website evaluation based on a review of the literature from 1995-2006. Information & Management, 47, 282-290. doi:10.1016/j.im.2010.06.002. [ Links ]

Chiou, W., Lin, C., & Perng, C. (2011). A strategic website evaluation of online travel agencies. Tourism Management, 32, 1463-1473. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2010.12.007. [ Links ]

Chung, T., & Law, R. (2003). Developing a performance indicator for hotel websites. Hospitality Management, 22, 119-125. doi:10.1016/S0278-4319(02)00076-2. [ Links ]

Correia, M.B., Ramos, C.M.Q., Rodrigues, J. M. F., & Cardoso, P. (2014). Framework for the Characterization of Hotel Websites. In P. Isaías & B. White (Eds.), Proceedings of the 13th International Conference WWW/Internet 2014 (pp. 333-337). Porto: IADIS Press. [ Links ]

Article history:

Submitted: 20.09.2015

Received in revised form: 13.12.2015

Accepted: 15.12.2015