Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies vol.12 no.1 Faro mar. 2016

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2016.12121

MANAGEMENT: SCIENTIFICPAPERS

Influence of entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacities in export performance

Influência da orientação empreendedora e das capacidades abortivas no desempenho das exportações

Alexandra Silva França1, Orlando Lima Rua2

1University of Minho, School of Economics and Management (EEC), Campus de Gualtar 4710-057 Braga, Portugal. E-mail: franca.alexandra@gmail.com

2Polytechnic Institute of Porto (IPP), School of Accounting and Administration of Porto (ISCAP); Applied Management Research Unit (UNIAG); Center for Studies in Business and Legal Sciences (CECEJ), 4200-465 Porto, Portugal. E-mail: orua@iscap.ipp.pt

ABSTRACT

The main purpose of this study is to analyze the influence that entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity have on export performance of small and medium-sized footwear companies. Therefore, this research adopted a quantitative methodological approach, conducting a descriptive, exploratory and transversal empirical study, having applied a questionnaire to a sample of Portuguese companies exporting footwear. From this study it was possible to conclude that entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity enhance export performance of Portuguese footwear companies in foreign markets. It also underline the contribution of this study to the theory of strategic management, since it is known that it encompasses deliberate and emerging initiatives, including the use of resources and capabilities to improve business performance. This study presents entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity as strategic determinants which contribute positively to the export performance.

Keywords: Entrepreneurial orientation, absorptive capacity, export performance, SMEs.

RESUMO

O objetivo fundamental deste estudo é analisar a influência que a orientação empreendedora e as capacidades absortivas têm no desempenho das exportações das pequenas e médias empresas de calçado. Para tal, adotamos nesta investigação uma abordagem metodológica quantitativa, realizando um estudo empírico descritivo, exploratório e transversal, tendo aplicado um questionário a uma amostra de empresas portuguesas exportadoras de calçado. Foi-nos possível concluir deste estudo que a orientação empreendedora e as capacidades absortivas melhoraram o desempenho das exportações das empresas portuguesas de calçado em mercados estrangeiros. Destacamos ainda a sua contribuição para a teoria da gestão estratégica, a qual abrange iniciativas deliberadas e emergentes, incluindo a utilização de recursos e capacidades para melhorar o desempenho do negócio. Este estudo apresenta a orientação empreendedora e as capacidades absortivas como determinantes estratégicos que contribuem positivamente para o desempenho das exportações.

Palavras-chave: Orientação empreendedora, capacidades absortivas, desempenho das exportações, PME.

1. Introduction

This study proposes to analyze the influence of entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity in export performance in Portuguese small and medium enterprises (SMEs) of footwear, where few studies have been made in order to understand how to enhance exports, vital for the recovery of economic and financial crisis. This choice was due to the importance that this industry assumes in the countrys development, since it has been the one that has positively contributed to the stability of Portuguese trade balance.

Entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity are thus strategic determinants which contribute to strategic formulation of economic policies and business management, designed to increase business performance in foreign markets, adding value to current context of change.

Currently, Portuguese companies are in a complex, dynamic and globalized context therefore is essential to recognize the strategic variables that influence and enhance growth in foreign markets, and contribute to improve medium and long term performance. Particularly capacities, for its dynamic character, that determines superior performance in a constant change market, with increasingly bolder competitors and demanding consumers.

Thereby, analysing strategic variables together with the knowledge of microeconomic reality, contributes to a more aware and efficient measures taken by economic agents that meets the challenges and constant change. However, in practice, there are many companies that still do not acknowledge the real importance of entrepreneurial orientation, as strategic posture, and absorptive capacity to maximize their internal and external efficiency, conditioning their development, expansion and survival. So, it is essential to carry out tests with intent to identify and analyze key strategic variables and, eventually, establish a relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity with business performance.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. Entrepreneurial orientation

For Miller (1983) entrepreneurial orientation emerged from entrepreneurship definition which suggests that a companys entrepreneurial degree can be measured by how it take risks, innovate and act proactively. Entrepreneurship is connected to new business and entrepreneurial orientation relates to the process of undertaking, namely, methods, practices and decision-making styles used to act entrepreneurially. Thus, the focus is not on the person but in the process to undertake (Wiklund, 2006).

Companies can be regarded as entrepreneurial entities and entrepreneurial behaviour can be part of its activities (Covin & Slevin, 1991). Entrepreneurial orientation emerges from a deliberate strategic choice, where new business opportunities can be successfully undertaken (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996). Thus, there is an entrepreneurial attitude mediating the vision and operations of an organization (Covin & Miles, 1999).

Several empirical studies indicate a positive correlation between entrepreneurial orientation and organizational growth (e.g. Miller, 1983; Covin & Slevin, 1991; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Wiklund, 2006; Davis, Bell, Payne & Kreiser, 2010; Frank, Kessler & Fink, 2010). Similarly, other studies also confirm that entrepreneurial orientation has a positive correlation with exports performance, enhancing business growth (e.g. Zahra & Garvis, 2000; Okpara, 2009).

The underlying theory of entrepreneurial orientation scale is based on the assumption that the entrepreneurial companies are different from the remaining (Kreiser, Marino & Weaver, 2002), since such are likely to take more risks, act more proactive in seeking new businesses and opportunities (Khandwalla, 1977; Mintzberg, 1973).

Entrepreneurial orientation has been characterized by certain dimensions that represent organization's behaviour. Starting from the Miller (1983) definition, three dimensions were identified: innovation, proactiveness and risk-taking, which collectively increase companies capacity to recognize and exploit market opportunities well ahead of competitors (Zahra & Garvis, 2000). However, Lumpkin and Dess (1996) propose two more dimensions to characterize and distinguish entrepreneurial process: competitive aggressiveness and autonomy. In this study only innovation, risk-taking and proactiveness will be considered, as they are the most consensual and used dimensions to measure entrepreneurial orientation (e.g. Covin & Miller, 2014; Covin & Slevin, 1989, 1991; Davis et al., 2010; Frank et al., 2010; Kreiser et al., 2002; Lisboa, Skarmeas & Lages, 2011; Miller, 1983; Okpara, 2009; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2005; Zahra & Covin, 1995; Zahra & Garvis, 2000).

2.2Absorptive capacity

In order to survive certain pressures, companies need to recognize, assimilate and apply new external knowledge for commercial purposes (Jansen, Van Den Bosch & Volberda, 2005). This ability, known as absorptive capacity (ACAP) (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990), emerges as an underlying theme in the organizational strategy research (Jansen et al., 2005).

Cohen and Levinthal (1990)presented a definition of ACAP most widely quoted by academic research, as the companies ability to identify, assimilate and exploit new knowledge. Thus, this ability access and use new external knowledge, regarded as an intangible asset, is critical to success and depends mainly on prior knowledge level, since it is this knowledge that will facilitate the identification and processing of new one. This prior knowledge not only includes the basic capabilities, such as shared language, but also recent technological and scientific data or learning skills. By analyzing this definition we found that absorptive capacity of knowledge has only three dimensions: the ability to acquire external knowledge; the ability to assimilate it inside; and the ability to apply it.

According to Zahra and George (2002) ACAP can be divided in Potential Absorptive Capacity (PACAP), including knowledge acquisition and assimilation, and Realized Absorptive Capacity (RACAP) that focuses on transformation and exploitation of that knowledge. PACAP reflects the companies ability to acquire and assimilate knowledge that is vital for their activities. Knowledge acquisition the identification and acquisition and assimilation is related to routines and processes that permit to analyze, process, interpret and understand the external information. RACAP includes knowledge transformation and exploitation, where transformation is the ability to develop and perfect routines that facilitate the integration of newly acquired knowledge in existing one, exploitation are routines which enhance existing skills or create new ones by incorporating acquired and transformed knowledge internally.

Jansen et al. (2005) defend that, although companys exposure to new knowledge, is not sufficient condition to successfully incorporate it, as it needs to develop organizational mechanisms which enable to synthesize and apply newly acquired knowledge in order to cope and enhance each ACAP dimension. Thus, there are coordination mechanisms that increase the exchange of knowledge between sectors and hierarchies, like multitasking teams, participation in decision-making and job rotation. These mechanisms bring together different sources of expertise and increase lateral interaction between functional areas. The system mechanisms are behaviour programs that reduce established deviations, such as routines and formalization. Socialization mechanisms create a broad and tacit understanding of appropriate rules of action, contributing to a common code of communication.

2.3Export performance

The development of exports is of great importance, both at macro and micro levels, contributing to economic and social development of nations, helping the industry to improve and increase productivity and create jobs. At company level, through market diversification, exports provide an opportunity for them to become less dependent on the domestic market, gaining new customers, exploiting economies of scale and achieving lower production costs while producing more efficiently (Okpara, 2009).

In this sense, exports is a more attractive way to enter international markets, especially for SMEs, in comparison with other alternatives, either joint ventures or setting up subsidiaries, which involve spending a large number of resources (e.g. Dhanaraj &Beamish, 2003; Piercy, Kaleka & Katsikeas, 1998), does not create high risk and commitment and allows greater flexibility in adjusting the volume of goods to different export markets (Lu & Beamish, 2002).

On one hand, a companys export activity starts to fulfil certain goals, which may be economic (such as increasing profits and sales) and / or strategic (such as diversification of markets, gaining market share and increasing brand reputation) (Cavusgil & Zou, 1994).

On the other hand, the export motivation may result from proactive or reactive actions. The proactive actions are advantage of profit, introduction of a single product, technological advantage, and exclusive information, commitment of management, tax benefits and economies of scale. The reactive motivations are identifying competitive pressures, excess production capacity, sales decrease in domestic market, saturation of domestic market and proximity of customers and landing ports (Wood & Robertson, 1997).

2.4 Relations between constructs

The literature suggests that each dimension of entrepreneurial orientation has a positive influence on business performance (Wiklund & Shepherd, 2005), since it increases the engagement with innovation, which contributes, for example, to create new products and services, seek new opportunities and new markets (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Miller, 1983). In this sense, innovative companies have an extraordinary performance and can even be seen as a countrys engine of economic growth (Schumpeter, 1934). Proactive companies can benefit from the advantages of being first-movers, achieving greater market share, charging higher prices and reaching the market before the competition (Zahra & Covin, 1995). Thus, these companies can control the market by mastering distribution channels and building brand recognition. With respect to risk-taking the connection to performance is less obvious, since there are projects that fail while others have long-term success (Wiklund & Shepherd, 2005). Hence, its intended to confirm the existence of this relationship and test the following working hypotheses:

• H1: Entrepreneurial orientation influence positive and significantly export performance.

• H1a. Innovation influences positive and significantly export performance.

• H1b. Proactiveness influences positive and significantly export performance.

• H1c. Risk-taking influences positive and significantly export performance.

Dynamic capability enable companies to create, develop and protect resources to achieve superior performance in the long run, are built (not acquired), experience dependent and are embedded in organizational processes (Ambrosini & Bowman, 2009), not directly affecting outputs, but contributing through the impact they have on operational capabilities (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997). Maintaining these capabilities requires a management that is able to recognize adversity and trends, configure and reconfigure resources, adapt processes and organizational structures in order to create and seize opportunities, while remaining aligned with customer preferences (Teece, 2007). In the same sense dynamic capabilities allow businesses to achieve superior long-term performance (Teece, 2007). Ultimately, the following hypotheses are tested:

• H2. Absorptive capacity influence export performance.

• H2a. The capacity of knowledge acquisition influence export performance.

• H2b. The capacity of knowledge assimilation influence export performance.

• H2c. The capacity of knowledge transformation influence export performance.

• H2d. The capacity of knowledge exploitation influence export performance.

3. Methodology

3.1Sample

To test the hypothesis a sample of Portuguese footwear companies was used, that meet the following criteria: companies in which at least 50% of income comes from exports of goods, or companies in which at least 10% of income comes from exports of goods and the export value is higher than 150,000 Euros (INE, 2011).

For information regarding companies the Associação Portuguesa dos Industriais de Calçado, Componentes, Artigos em Pele e seus Sucedâneos (APICCAPS) was contacted. We were provided with a database of 231 companies (company name, telephone contact, email, CAE, export markets, export intensity and capital origin). Only 167 companies fulfilled the parameters, and were contacted by email by APICCAPS to respond to the questionnaire. Subsequently, all companies were contacted by the authors via e-mail and telephone, to ensure a higher rate of valid responses. The questionnaires began on April 22, 2014 and ended on July 22, 2014. After finishing the data collection period, 42 valid questionnaires were received, representing a 25% response rate. According to Menon, Bharadwaj and Adidam Edison (1999) the mean response rate of top management is between 15% and 20%, so the rate of this study is quite satisfactory.

In this investigation we chose a non-probabilistic and convenient sample since its respondents were chosen for being members of APICCAPS.

3.2 Measure instrument and data collection process

From Millers (1983) definition 3 dimensions were indentified for entrepreneurial orientation: innovation, proactiveness and risk-taking. Although the literature considers more dimensions, this literature review confirmed that these three dimensions are the most widely used in empirical research. The scale used is from Covin & Slevin (1989) and consist in nine items: three for innovation, three for proactiveness and three for risk-taking, having been used a five point Likert scale, where 1 means strongly disagree and 5 strongly agree.

To measure absorptive capacity construct, and based in Jansen et al. (2005), it was operationalized the company's ability to acquire new knowledge through six questions, assimilate it through three questions, transform it through three questions and the ability to explore new external knowledge into their current operations, through six questions (e.g. Jansen et al., 2005; Zahra & George, 2002). A five point Likert scale was used to measure each item, where 1 means strongly disagree and 5 strongly agree.

Okparas scale (2009) was used to assess export performance, comprising profitability indicators of sales growth, profit, activities, operations and performance in general. A five point Likert scale was used to measure each item, where 1 means strongly disagree and 5 strongly agree.

Data collection was implemented through electronic questionnaire, associating a link to the survey that was online. To prepare it we used limesurvey, version 1.91. To reduce misunderstandings, the questionnaire was validated by the research department of APICCAPS. The analysis unit used in this research was export venture.

4. Results and analysis

4.1 Reliability Analysis

In order to verify the reliability of overall variables we estimated the stability and internal consistency through Cronbach's alpha (a). In general, an instrument or test is classified with appropriate reliability when a is higher or equal to 0.70 (Nunnally, 1978). However, in some research scenarios in social sciences an a of 0.60 is considered acceptable, as long as the results are interpreted with caution and the context is taken into account (DeVellis, 2012). For the present study we used the scale proposed by Pestana & Gageiro (2008).

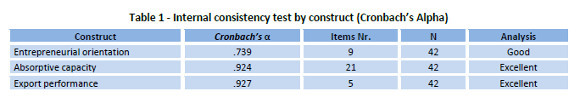

The result of 0.932 achieved for all of variables is considered excellent, confirming the samples internal consistency. It was also conducted an internal consistency test for all variables in each construct to assess their reliability (Table 1).

We found that absorptive capacity and export performance have excellent consistency, except entrepreneurial orientation that presents good reliability.

4.2 Exploratory factor analysis

4.2.1Entrepreneurial orientation

We performed a factor analysis, with Varimax rotation, of the entrepreneurial orientation construct items that comprise the scale, with the purpose of finding a solution that was more easily interpretable. Three factors were extracted and there was no need to delete items.

Thus, we obtained a scale composed of 9 items, distributed over three factors that explain 77.09% of total variance, with 35.52% of variance explained by the first factor (called Proactiveness, which gather three items whose saturations range between 0.887 and 0.786), 27.48% for the second factor (named Innovation and is divided into three items and their saturations range between 0.856 and 0.840) and 14.09% by the third factor (called Risk-taking, composed of three items, whose saturations range between 0.918 and 0.770). Analyzing the internal consistency of the three factors, we found that Cronbach's Alphas are a=0.852, a=0.825 e a=0.816, respectively, values that signify the three sub-dimensions have a very good internal consistency. KMO test indicates that there is a reasonable correlation between the variables (0.695). Bartletts sphericity test registered a value of c2(36, N = 42) =171.176, p<0.05, therefore is confirmed that χ2>χ0.952, so the null hypothesis is rejected, i.e. the variables are correlated.

4.2.2Absorptive capacity

In the factor analysis, with Varimax rotation, of these construct we got a scale with 21 items, distributed by 5 factors, that explained 73.89% of total variance: 44.35% by the first factor (Knowledge Exploitation, with 7 items, whose saturations range between 0.838 and 0.328), 10.92% by second factor (Knowledge Assimilation, with 4 items, whose saturations range between 0.807 and 0.670), 8.28% by third factor (General Knowledge Acquisition, with 3 items, whose saturations range between 0.768 and 0.670), 5.46% by fourth

factor (Knowledge Acquisition in the Industry, with 3 items, whose saturations range between 0.816 and 0.404) and 4,88% by the fifth factor (KnowledgeTransformation, with 2 items, whose saturations range between 0.696 and 0.580).

The internal consistency of the five factors are a=0.931, a=0.860, a=0.710, a=0.650 e a=0.796, respectively, for the 1st 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th factors. These values indicate that these dimensions presented a reasonable and excellent internal consistency. KMO test confirm a medium correlation between the variables (0.796). Bartlett's sphericity test registered a value of c2(210, N=42) =630.742, p<0.05, therefore is confirmed that c2>c0.952, so the null hypothesis is rejected and the variables are correlated.

3.2.3Export performance

Lastly, in the factor analysis, with Varimax rotation, of these construct we got a scale with one factor and there was no need to delete items. A scale with 5 items was obtained, which explained 77.9% of total variance, whose saturations range between 0.918 and 0.850.

The internal consistency is excellent (a=0.927). KMO test point to a good correlation between the variables (0,814). Bartletts sphericity test registered a value of ρ2(10, N=42) =171.982, ρ<0.05, therefore is confirmed that c2>c0.952, so the null hypothesis is rejected and the variables are correlated.

4.3 Multiple linear regression

In linear regression the coefficient of determination R2 measures the proportion of total variability that can be explained by regression (0=R=1), measuring the effect of independent variables on the dependent variable (Marôco, 2011).

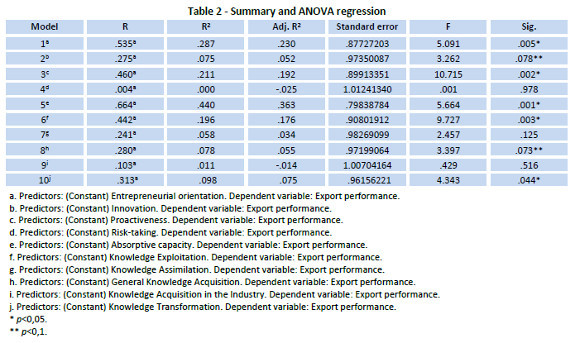

We carried out a multiple linear regression analysis linking the variables of the studied constructs. The coefficient of determination R2 measures the proportion of total variability that can be explained by regression, while the ANOVA regression provide information about levels of variability within a regression model, form a basis for tests of significance and allows to test the hypotheses: H0: ρ2=0 vs. H1: ρ2≠ 0 (Table 2).

The previous table presents for model 1 a value of F=5.091, with ρ-value=0.005 (Sig.), so H0 is rejected in favour of H1. For model 3 we have obtained a value of F=10.715, with ρ-value=0.002 (Sig.), so H0 is rejected in favour of H1b. Model 5 present a value of F=5.664, with ρ-value=0.001 (Sig.), so H0 is rejected in favour of H2. For model 6 is observed a value of F=9.727, with ρ-value=0.003 (Sig.), so H0 is rejected in favour of H2a. Model 10 present a value of F=4.343, with ρ-value=0.044 (Sig.), so H0 is rejected in favour of H2e. These hypotheses are thus backed, considering a significance level p<0.05. However, for model 2 there is a value of F=3.262, with ρ-value=0.078 (Sig.), so H0 is rejected in favour of H1a, while model 8 presents a value of F=3.397, with ρ-value=0.073 (Sig.), so H0 is rejected in favour of H2c. These hypotheses are also supported, considering a significance level ρ<0.1, being the remainder ones unsupported.

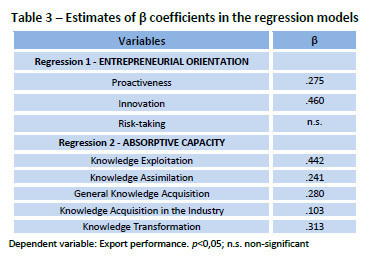

A mere comparison of the regression coefficients is not valid to evaluate the importance of each independent variable models, since these variables have different magnitudes. Thus, it is essential to use standard variables, known as Beta (ß) coefficients, in the models adjustment so that the independent variables can be compared. By analyzing the standardized Beta coefficients (Table 3) it is confirmed which variables have higher contribution to exports performance.

On one hand, from the entrepreneurial orientation perspective Innovation (ß=0.460) and Proactiveness (ß=0.275) and, on the other hand, from the absorptive capacity perspective, a Knowledge Exploitation(ß=0.442), a Knowledge Transformation(ß=0.313) and a General Knowledge Acquisition (ß=0.280) are the ones that have higher relative contributions to explain exports performance.

5. Conclusions

Overall, the results of this study support the view that entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity contributes to exports performance.

Is important to note that companies evaluated constructs with reference to their main competitors and export markets, so the results should be interpreted based on these two aspects.

The Portuguese footwear industry faces considerable challenges, not only concerning the international markets crisis, but also regarding consumption patterns. The reduction of shoe design lifecycles has consequences on the offer. On one hand, the products have to be adapted to different segments specific needs and tastes (custom design, new models in small series, etc.), on the other hand, manufacture processes must be increasingly flexible, adopt just-in-time production, invest in the brand, qualified personnel, technology and innovation.

In recent decades this industry has been subject to enormous pressure from large international brands. However, although few in number some companies risked launching their own brand into the market. Entrepreneurial orientation and dynamic capabilities were crucial in this process, by allowing companies to permanently evolve, follow the needs and market trends, in order to achieve superior exports performance in foreign markets.

According to the results, entrepreneurial orientation contributes to exports performance, with particular emphasis on innovation and proactiveness. This study also demonstrated that the company's absorptive capacity has a positive and significant influence on their performance, especially knowledge exploitation, knowledge transformation and general knowledge acquisition. The analyzed companies are able to acquire, transform and exploit knowledge through informal knowledge gather, clear definition of tasks, analysis and discussion of market trends and new product development, among others.

Therefore, in conclusion, this industry has yet a long and hard way to go. The industrial structure has a high number of family businesses, weak competitiveness mainly due to management skills deficit and is overly concentrated in Europe as an exports market destination. These are some of the points to be overcome by this industry.

5.1 Theoretical and practical implications

From this study emerge important contributions to theory and practice, the results are relevant to researchers, business managers, public and government entities, since it explores the complementarity between the theory of entrepreneurship andDynamic Capabilities View (DCV), by incorporating them into strategic determinants analysis. The findings are a contribution to clarify its influence on the companys exports performance. Additionally, it contributes to develop concepts as well as to define scales. The operationalization of the constructs entrepreneurial orientation, absorptive capacity and export performance allowed measurement through common and identifiable characteristics between organizations.

This study also enabled a detailed analysis of a highly important industry for national exports, such as of footwear industry, allowing understanding that entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity, as an industry strategic determinant, enhance exports performance.

Innovation can occur throughout a new product line process, advertisement or technological advances (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996). There are several ways to identify a companys innovation degree, such as financial resources volume invested in innovation, human resources allocated to innovation activities, number of new products or services launched on the market or change frequency in product lines or services (Covin & Slevin, 1989). Proactiveness can be critical to entrepreneurial orientation, as it emerges from a long-term perspective, which is accompanied by innovation activities or new businesses (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996). This study confirms that these two dimensions are preponderant for exports performance.

Jansen et al. (2005) defend that companies need to develop organizational mechanisms to combine and apply newly acquired knowledge in order to deal and enhance each absorptive capacity dimension. In this study is notorious the importance of knowledge absorptive capacity to business performance. It is essential that business owners are able to interpret, integrate and apply external knowledge in order to systematically analyze change in the target market and to incorporate this knowledge in their processes to enhance performance.

Lastly, this study makes an important contribution to the theory of strategic management. It is known that strategy includes deliberate and emergent initiatives adopted by management, comprising resource and capabilities use to improve business performance (Nag, Hambrick & Chen, 2007). To stay competitive, companies must make an internal assessment in order to find what resources and capabilities give them advantage over competitors. Thus, the challenge of strategy consists in selecting or creating an environmental context where capabilities and resources can provide competitive advantages (Porter & Montgomery, 1998). Hence, this study presents entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity as strategic determinants that contribute to the clarification of export performance.

5.2 Research limitations

As in any research, methodology, procedures adopted, analysis and empirical study results interpretation always present alternatives and limitations.

The main limitation of this study relate to the sample size, since it was difficult to find companies with willingness to collaborate in this type of research.

A five points Likert scale was used to measure the constructs. Most responses were based on subjective judgment of respondents. Although the literature identifies the advantages of subjective measures to evaluate exports performance, it is recognized that some answers may not represent the reality of business performance in foreign markets.

The fact that the research does not consider the effect of control variables such as size, age, location and target market of the respondents can be seen as a limitation.

5.3 Future lines of research

Wherever scientific research is developed, which adopts specific type of approach leaves open field so that the same topic can be addressed by other perspectives, using different techniques or adding new knowledge.

This study incorporated a set of constructs for which there was need to define measures and scales. To study the validity and reliability, statistical analyzes was used that allowed to evaluate the scales associated with the constructs model. In future work, we suggest that the model is used in a sample with a higher number of observations to confirm these results.

Finally, we suggest pursuing with the investigation of strategic management in Portugal, focusing in other sectors of national economy, so that in the future one can make a comparison with similar studies, allowing to realize and find new factors that enhance exports performance.

References

Ambrosini, V. & Bowman, C. (2009). What are dynamic capabilities and are they a useful construct in strategic management? International Journal of Management Reviews, 11(1), 29–49. [ Links ]

Cavusgil, T. & Zou, S. (1994). Marketing strategy-performance relationship: an investigation of the empirical link in export market ventures. Journal of Marketing, 58(1), 1–21. [ Links ]

Cohen, W. M. & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128. [ Links ]

Covin, J. & Miles, M. (1999). Corporate entrepreneurship and the pursuit of competitive advantage. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 23(3), 47–63. [ Links ]

Covin, J. & Miller, D. (2014). International entrepreneurial orientation: Conceptual considerations, research themes, measurement issues, and future research directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(1), 11–44. [ Links ]

Covin, J. & Slevin, D. (1989). Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strategic Management Journal, 10(1), 75–87. [ Links ]

Covin, J. & Slevin, D. (1991). A conceptual model of entrepreneurship as firm behavior. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 16, 7–25. [ Links ]

Davis, J. L., Bell, R. G., Payne, G. T. & Kreiser, P. M. (2010). Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: The moderating role of managerial power. American Journal of Business, 25(2), 41–54. [ Links ]

DeVellis, R. F. (2012). Scale development - theory and applications (3er ed.). Chapel Hill: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Dhanaraj, C. & Beamish, P. W. (2003). A Resource-based approach to the study of export performance. Journal of Small Business Management, 41(3), 242–261. [ Links ]

Frank, H., Kessler, A. & Fink, M. (2010). Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance-a replication study. Schmalenbach Business Review, (April), 175–199. [ Links ]

Jansen, J. J. P., Van Den Bosch, F. A. J. & Volberda, H. W. (2005). Managing potential and realized absorptive capacity: How do organizational antecedents matter? Academy of Management Journal, 48(6), 999–1015. [ Links ]

Khandwalla, P. N. (1977). Some top management styles, their context and performance. Organization & Administrative Sciences, 7(4), 21–51. [ Links ]

Kreiser, P., Marino, L. & Weaver, K. (2002). Assessing the psychometric properties of the entrepreneurial orientation scale: A multi-country analysis. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26(4), 71–94. [ Links ]

Lisboa, A., Skarmeas, D. & Lages, C. (2011). Entrepreneurial orientation, exploitative and explorative capabilities, and performance outcomes in export markets: A resource-based approach. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(8), 1274–1284. [ Links ]

Lu, J. W. & Beamish, P. W. (2002). The Internationalization and Growth of SMEs. ASAC 2002, 86–96. [ Links ]

Lumpkin, G. & Dess, G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 135–172. [ Links ]

Marôco, J. (2011). Análise estatística com o SPSS Statistics. (5a ed.). Pêro Pinheiro: ReportNumber. [ Links ]

Menon, A., Bharadwaj, S. G., Adidam, P. T. & Edison, S. W. (1999). Antecedents and consequences of marketing strategy making: A model and a test. Journal of Marketing, 63(2), 18-40. [ Links ]

Miller, D. (1983). The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Management Science, 29(7), 770–791. [ Links ]

Mintzberg, H. (1973). Strategy-making in three modes. California Management Review, 16(2), 44–53. [ Links ]

Nag, R., Hambrick, D. & Chen, M. (2007). What is strategic management, really? Inductive derivation of a consensus definition of the field. Strategic Management Journal, 28(9), 935–955. [ Links ]

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Okpara, J. (2009). Entrepreneurial orientation and export performance: evidence from an emerging economy. International Review of Business Research Papers, 5(6), 195–211. [ Links ]

Pestana, M. H. & Gageiro, J. N. (2008). Análise de Dados para Ciências Sociais - A complementaridade do SPSS. (5a ed.). Lisboa: Edições Silabo. [ Links ]

Piercy, N., Kaleka, A. & Katsikeas, C. (1998). Sources of competitive advantage in high performing exporting companies. Journal of World Business, 33(4), 378–393. [ Links ]

Porter, M. & Montgomery, C. A. (1998). Estratégia: a busca da vantagem competitiva. Rio de Janeiro: Campus. [ Links ]

Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The theory of economic development. New Brunswick (USA) and London (UK): Transaction Publishers. [ Links ]

Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities?: the nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(3), 1319-1350. [ Links ]

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G. & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533. [ Links ]

Wiklund, J. (2006). The sustainability of the entrepreneurial orientation–performance relationship. In P. Davidsson, F. Delmar & J. Wiklund, J. (eds.), Entrepreneurship and the Growth of Firms, (pp. 141–155). Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Wiklund, J. & Shepherd, D. (2005). Entrepreneurial orientation and small business performance: a configurational approach. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(1), 71–91. [ Links ]

Wood, V. R. & Robertson, K. R. (1997). Strategic orientation and export success: an empirical study. International Marketing Review, 4(6), 424–444. [ Links ]

Zahra, S. & Covin, J. G. (1995). Contextual influences on the corporate entrepreneurship-performance relationship: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 10(1), 43–58. [ Links ]

Zahra, S., & Garvis, D. (2000). International corporate entrepreneurship and firm performance: The moderating effect of international environmental hostility. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5/6), 469–492. [ Links ]

Zahra, S., & George, G. (2002). Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. Academy of Management Review, 27(2), 185–20. [ Links ]

Article history:

Submitted: 12.10.2015

Received in revised form: 13.01.2016

Accepted: 16.01.2016