Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.13 no.1 Faro mar. 2017

MANAGEMENT - SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Investigating the influencers of materialism in adolescence

Investigando os Influenciadores do Materialismo na Adolescência

Marcelo de Rezende Pinto*, Alisson Oliveira Mota**, Ramon Silva Leite***, Ricardo César Alves****

*Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais, Av. Itaú, 525, Bairro Dom Cabral - CEP, 30535-012 Belo Horizonte - MG, Brazil, marcrez@hotmail.com

**Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais, Av. Itaú, 525, Bairro Dom Cabral - CEP, 30535-012 Belo Horizonte - MG, Brazil, alisson.mota@gmail.com

***Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais, Av. Itaú, 525, Bairro Dom Cabral - CEP, 30535-012 Belo Horizonte - MG, Brazil, ramonsl@pucminas.br

****Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais, Av. Itaú, 525 Bairro Dom Cabral - CEP, 30535-012 Belo Horizonte - MG, Brazil, rcesar.alves@uol.com.br

ABSTRACT

This work presents results of a research whose objective was to identify the influencers attributes in degree of materialism among Brazilian adolescents. The literature review has contemplated discussions about the materialism among adolescents that culminated in the proposition of a theoretical model to be tested empirically. The model was composed of three influencer variables materialism (age, economic class, gender) and by seven influencer constructs (communication with friends, communication with parents, effect of peers, media exposure, attitudes to the adverts, attraction of celebrities and self-esteem). The field research involved 1.353 adolescents aged 11 to 18 years of primary and secondary education, from private and public schools. For the data analysis modeling of structural equations was used. Among the results, we can highlight the significant influence of constructs of communication with friends and effect of peers in the degree of materialism among adolescents.

Keywords: Consumption, materialism, effect of peers, attraction of celebrities, adolescents.

RESUMO

Este artigo apresenta resultados de uma pesquisa cujo objetivo foi identificar os atributos influenciadores no nível de materialismo entre adolescentes no Brasil. A revisão da literatura contemplou discussões acerca do materialismo entre adolescentes que culminaram na proposição de um modelo teórico a ser testado empiricamente. O modelo foi composto por três variáveis influenciadoras do materialismo (idade, classe econômica e gênero) e sete construtos influenciadores (comunicação com os amigos, comunicação com os pais, efeito de pares, exposição à mídia, atitudes frente à publicidade, atração de celebridades e auto-estima). O trabalho de campo envolveu 1.353 adolescentes com idade entre 11 a 18 anos de escolas públicas e privadas em nível de educação fundamental e médio. Para a análise dos dados a modelagem de equações estruturais foi utilizada. Entre os resultados, pode-se enfatizar que os maiores influenciadores do nível de materialismo entre adolescentes são os construtos comunicação com os amigos e efeitos de pares.

Palavras-chave: Consumo, materialismo, efeito de pares, atração de celebridade, adolescentes.

1. Introduction

Currently, it seems to be gaining the importance that the consumption and the relation between persons and goods have been acquiring to explain various phenomena in a context called "consumer society", "post-industrial society" and "post-modern society" (McCracken, 2003; Barbosa, 2006). This whole discussion seems to bring to light a concept that has been gaining prominence in recent decades, that is the materialism. Larsen, Sirgy and Wright (1999) attempt to throw light on the theme to propose that, in common use, the word materialism refers to the belief that material objects are important and valuable to our daily life. Thus, a materialistic subject would be one that values the material objects. These authors, when supporting in the defense that the concept has positive and negative dimensions, they try to define it in theory as the level at which individuals or groups value the material possessions.

In Brazil, it is possible to find studies involving the theme, although all of them were published from the mid 2000: Scaraboto, Zilles and Rodriguez (2005), Moura (2005), Moura, Aranha, Zambaldi and Ponchio (2006), Fernandes and Santos (2006), Ponchio, Aranha and Todd (2006), Ponchio and Aranha (2007), Grohmann, Batistella, Beuron, Riss, Carpes and Lutz (2011), Santos and Souza (2012).

When redeeming these studies, it is possible to find some gaps related to the theme of materialism which still have not been adequately investigated in the Brazilian context. One of these gaps refers to the issue of subcultures of age, mainly when it comes to adolescents. This public seems to compose a significant portion of the Brazilian population, because it is estimated that the population of individuals in this year’s stratum is around 30,7 million, according to Renato Meirelles, President of the Institute Data Popular (IDP, 2013). On the whole, these young consumed, only in the year 2013, a value close to R$ 239.8 billion.

Facing this context, questions that "drained" began to arise on interest in conducting a survey with the following objective: to identify the possible influencer attributes in degree of materialism among adolescents in the Brazilian context.

The search appears to have characteristics that make it relevant and timely. From the theoretical point of view, the study aims to fill a gap regarding the influencers of materialism in the adolescent population in Brazil. The themes involved in work throw light in issues that are expensive to the field of macro marketing, besides bordering discussions related to the effects of marketing activities on individuals, in the case of work, the adolescent audience. Finally, it is worth mentioning that, from a practical point of view, the work comes to add up to others in order to contribute to the knowledge of a public which is observed an expressive consumption.

The next section attempts to make a brief review of the literature involving the thematics, submit the conceptual model and outline the research hypotheses.

2. Review of the literature, research hypotheses and conceptual model

2.1 Materialism in adolescence

In the field of consumer behavior, it is difficult not to mention two studies that were relevant to the operationalization of the construct materialism, developed in the 1980s. The first was developed by Belk (1985) and reports the materialism as a personality trait associated to possession, the lack of generosity and envy. In this work, the author comments that with this construct, you can measure the characteristics of consumers, based on importance that consumers attach to their possessions. In addition, it is possible to consider a scale widely adopted in the context of consumer behavior, proposed by Richins and Dawson (1992). The scale of material values considers the materialism a value composed by centrality, happiness and success. This second construct of measurement of materialism, appeared only in the following decade (1990), with the aim of understanding and assessing the levels of materialism of consumers his measures materialism from scale of values and attitudes, which is based on three dimensions: Centrality, happiness and success.

The correlation of the theme materialism and adolescents is mentioned by Churchill and Moschis (1979). They have created a structural model concerning the consumer adolescent. These authors have explored the effects of both the structural social variables ( social variables, such as social class, gender and birth order, which can have an effect on the socialization, influencing the learning processes) and socialization agents (family, television and their peers) on variables of economic criterion for consumption (cognitive orientation about the importance of the functional characteristics and of the economic aspects of products), social motivation for consumption (cognitive orientation, emphasizing conspicuously consumption and its importance for their own expression), and materialistic values.

Based on the revised literature, several explanations about the materialistic behavior of adolescents and their possible influencers are proposed, although empirical studies on the subject are up to the moment, fragmented. Following are the discussions that gave support to the hypotheses.

2.2 Gender

The correlation between materialism and gender of the adolescents was studied by Achenreiner (1997), Churchill and Moschis (1978, 1979), Moore and Moschis (1981) who indicated positive relationship. The authors suggest that the male gender contains higher materialistic scores than women. According to Miller (1998), girls compared with boys have demonstrated to be more careful and to take a greater interest in the purchase activity. Women have a greater tendency to consider the activity of purchase as pleasurable (Dholakia,1999; Buttle, 1992). On the other hand, men see the activity of purchase as a necessity and as purely motivated by buying in itself (Campbell, 1997). So, as hypothesis:

H1: Boys show a greater degree of materialism than girls.

2.3 Age

Regarding age, the research results involving materialism of adolescents do not match. Studies conducted by the authors as Belk (1985), Richins and Dawson (1992), Micken (1995) and Watson (1998, 2003) found out a relation between materialism and the age of the respondents. Now Churchill and Moschis (1979), Moore and Moschis (1981) reported a decrease in the materialistic thinking with the increase of age. And still, the results of Achenreiner (1997), who researched children and adolescents between 8 and 16 years, found no relationship between these variables, indicating indifference between the attitudes of consumption and the age range of the respondents. In this case, it was opted for the proposition of the following hypothesis:

H2: The greater the age, the higher the degree of materialism of the adolescents.

2.4 Economical class

It is possible to find studies that considered the relation of materialism with the variable income of adolescents. Riesman, Glaser and Denny (1950) found that in families of superior income, children acquire some knowledge of the purchase process at an early age. Previous researches supported this reasoning line: adolescents of high income family are more aware in their purchasing decisions (Ward, 1974; Churchill & Moschis, 1978; Moore & Moschis, 1978). Applied studies with young people by Richins and Dawson (1992) and Watson (2003) found no relationship between materialism and the income of the interviewees, since individuals considered materialistic were allocated in all economic classes. Now investigations conducted by Churchill & Moschis (1979) and Moore & Moschis (1981) indicated that children with high incomes are more aware of their purchases, differently from low income.

In the case of the research, in view of the difficulty that could be generated for the adolescent inform the income of their family, it was to be more appropriate to take into account the economic class. Thus, it has come to the following research hypothesis:

H3: The adolescents from a better social economical class present a lower materialism degree than the ones from an inferior social class.

2.5 Self-esteem

According to Coopersmith (1967), the self-esteem is the judgment that the individual makes, and that routinely feeds, in relation to himself. In the literature regarding the consumption, it is possible to find some studies that seek to investigate the relationship between materialism and self-esteem (Blascovich & Tomako, 1991; Jindal-Snape & Miller, 2008; Cramer, 2003; Banister & Hogg, 2004). Specifically, with adolescents, a study conducted by Darley (1999) examined the effects of self-esteem, discovering that the intrinsic motivation (enjoyment of purchases) is a significant predictor of the research effort and perception product knowledge. From these considerations, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H4: Adolescents with low self-esteem have a higher degree of materialism.

2.6 Exposure to media

Some studies have attempted to correlate the time of exposure to the media and the degree of materialism: Ward and Wackman (1971), Atkin (1975), Churchill and Moschis (1978), Churchill and Moschis (1979) e Moschis and Moore (1982). Moschis and Moore (1982) showed a significant relationship between the consumption of publicity and awareness of the role of the consumer. The effects of the media may be mediated and partially neutralised by other socialization agents (Moschis & Moore, 1982; Moschis, Moore & Stanley, 1984), in particular by parents, whose moderator role, for example, the media exposure has deserved and continues to receive special attention of researchers and society (Carlson, Lacziniak & Wertley, 2011). This way, a hypothesis arises:

H5: There is a positive relationship between time of exposure to the media and degree of materialism among adolescents.

2.7 Celebrities attraction

A survey conducted by Boon and Lomore (2001) indicated thaadolescents had a connection with their favorite celebrities and that were more prone to induce their choice. Furthermore, the adolescents admitted that, in addition to the physical and appearance, their idols also had some influence on their values of personal attitudes, such as ethical and moral values. Another empirical research carried out by Martin and Bush (2000) showed that adolescents are influenced by media celebrities in the choice of a brand. Lafferty and Goldsmith (1999) affirmed that adolescent consumers are more prone to use products that are disseminated by media attractive celebrities. Kahle and Homer (1985) have tried to explain the attraction of celebrities and its materialism level. In view of these considerations, we proposed the hypothesis that:

H6: Adolescents who reported high level of attraction by celebrities will be more materialistic.

2.8 Attitudes to the television adverts

Churchill and Moschis (1978, 1979) detected a statistically significant association between the strength of favorable attitudes to materialism and the propensity to accept the content of television commercials. In his studies, Chan (2013) also lists positively the propaganda to materialism. In the United States, studies conducted by Bybee, Robinson and Turow (1985) stated that young spectators devoted themselves to TV and their ads, are more vulnerable to materialistic values. Similar results were found in samples from South Korea (Kwak, Zinkhan & Dominik.,2002), among the adolescents in China (Chan, 2013; Gu & Hung, 2009) and other emerging economies (Smith & Roy, 2008), all of them associating the power of the manipulation of advertising and its influence in the materialistic values. Like this, it can be proposed the following hypothesis:

H7: Adolescents with positive attitudes to the television adverts will have a higher level of materialism.

2.9 Social comparation: communication with parents and peers effect.

For Moschis (1987), children and adolescents "learn" models of consumption through multiple agents of socialization such as parents, friends, colleagues, school, shops, media, among other products. It would be appropriate to emphasize that the two main sources of social influences would be parents and peers.

Regarding the communication with the parents, Churchill and Moschis (1978) conducted studies investigating the relationship of consumption between parents and children and arrived two dimensions in family communication. The first, called "socio-oriented", is the type of communication planned to produce respect and nourish harmonic and pleasant social relations at home. The second called “concept oriented", focuses on positive restrictions and tries to help young people to develop their own points of view in relation to the world. Churchill and Moschis (1978) still point that another important contribution of the family to the socialization of consumption of adolescents is the teaching of "rational" aspects of consumption.

Now regarding to peers, they seem to be one of the sources of interpersonal influence that affect children since they are small, and whose effect is accentuated in adolescence (Berger, 2003; Brechwald & Prinstein, 2011; John, 1999). The effect of peers has already been previously studied by Bearden and Etzel (1982), Childers and Rao (1992) and Bachmann, Deborah and Akshay (1993), Lachance, Beaudion and Dobitaille (2003) and Yoh (2005), comparing purchasing decisions in several product lines. The influence of the peers determines the behavior of the consumer before, during and after the purchasing act (Mangleburg, Doney and Bristol, 2004). The peers help assess products, brands and shops in order to increase feelings of belonging to the group (Mangleburg et al., 2004) and be in accordance with the standards of the group which are exemplified by the possession of products (Moschis & Mitchell, 1986) Thus, the interaction with the peers has recognized importance in the process of development of the role of consumers in children and adolescents (John, 1999). Communication with peers between adolescents significantly influences their attitudes and behavior of the consumer (Churchill & Moschis, 1978; Moschis, 1985). Thus, it was deemed appropriate to consider the following hypothesis:

H8: Adolescents who perceive a high level of social influence including parents and peers will be more materialistic.

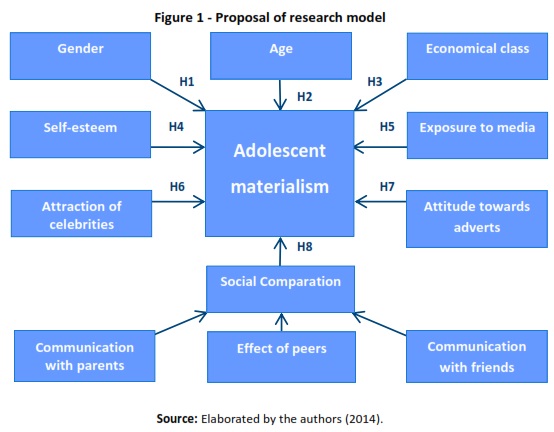

2.10 Conceptual model

From the discussion conducted previously, a conceptual model of the research could be drawn up (Figure 1).

Proposed the research hypothesis and the presentation of a conceptual model, the next section will present the methodological procedures of empirical research.

3. Method

A survey was conducted among adolescents 11 to 18 years enrolled in nine public and private schools of fundamental and secondary school in the city of Belo Horizonte. These adolescents were interviewed in the classroom. 1.353 questionnaires were obtained. However, 216 questionnaires were excluded due to having missing value, which resulted in a sample of 1137 valid questionnaires that were, in fact, used in the analysis. The data collection occurred between the months of September and October 2014.

Regarding the scales, presented below, it is worth mentioning that they were duly adapted and validated to be used in Brazil through the technique of parallel translation (Malhotra, 2006). It is worth stressing that the instrument has gone through a pre-test process to detect possible problems of understanding of the issues. The participants responded to the items using a Likert scale that varied from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (Fully agree). Only the scale of exposure to media presented a different form with open questions corresponding to the time in which the interviewee uses the media.

§ Profile questions: 5 questions related to the profile of the interviewee school, sex, age, school background of the head of the family and income;

§ Questions referring to the Brazilian Economic Classification Criteria;

§ Media exposure scale (5 open questions): pertaining to the time that the interviewee uses the TV, internet, social networks, newspapers and magazines. Adapted from previous studies developed by Chan and Prendergast (2008);

§ Scale Materialism among adolescents (10 questions): adapted from previous studies developed by Goldberg, Gorn, Peracchio and Bamossy (2003);

§ Scale communication with parents (3 questions): adapted from previous studies developed by Chan (2013);

§ Scale communication with friends (3 questions): adapted from previous studies developed by Chan (2013);

§ Scale Influence of peers (10 questions): adapted by Goldberg et al. (2003) in the work of Opree, Buijzen and Reijmersdal (2013);

§ Self-esteem scale (4 questions): adapted Rosenberg (1965) at work of Blascovich and Tomaka (1991);

§ Scale attraction of celebrities (7 questions): adapted from previous studies developed by Kwan (2013);

§ Scale attitudes front to the adverts (10 questions): adapted from previous studies developed by Kwan (2013);

In the phase of data analysis, initially, a global measurement for each of the constructs was calculated from the simple arithmetic average of the answers given to questions that worked as their respective indicators. It was used the modeling of structural equations (MEE) which is a "multivariate technique that combines aspects of factorial analysis and multiple regression that allows the researcher to examine simultaneously a series of dependence relations inter-related between the variables measured and latent constructs (latent variables), as well as several various latent constructs” (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson and Tathan, 2009, p. 542). It is worth highlighting that the analysis was divided into two steps. The first has estimated the parameters of each. The second sought to establish the model of structural equations that allowed to verify the set of relations between these constructs and intensity in which they occur. In both steps the software SPSS v. 20 and Amos v. 18 were used.

4. Results

4.1 Descriptive analysis

The descriptive analysis of the data showed that 51.3% of the sample was composed by male adolescents and 48.7% females. Regarding age, it was observed that the highest stratum (20.8%) of the adolescents indicated to be 13 years old, followed by the group of adolescents from 17 years old which corresponded to 16.9% of the sample. Now in terms of economic class, most of the respondents (74.3%) fitted in classes C1, B1 and B2.

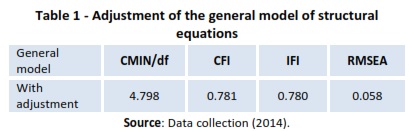

4.2 Model

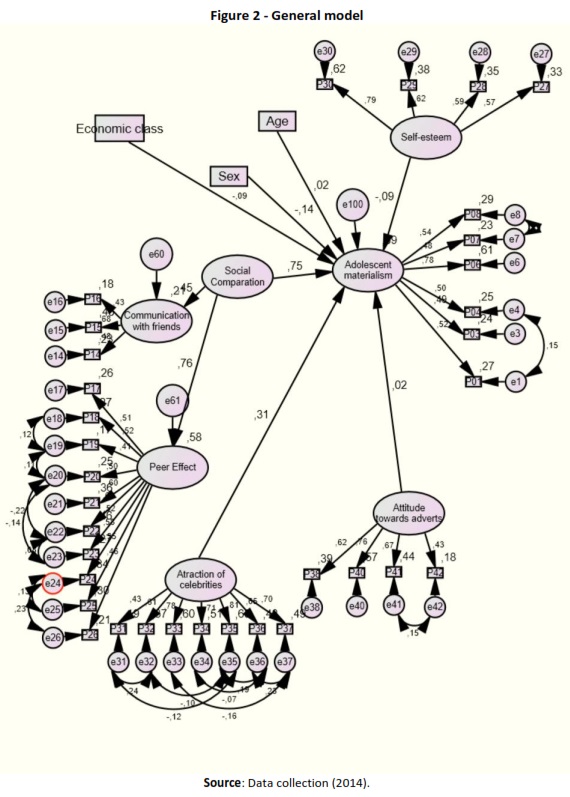

It is worth considering that, initially, it was verified the reliability of constructs considered in the model through the Cronbach Alpha (Malhotra, 2006). With the exception of the construct communication with parents (that presented an alpha of 0.53) and media exposure construct (that presented an alpha of 0.45), all the constructs had satisfactory reliability. Thus, the constructs communication with parents and media exposure were eliminated from the analysis. In sequence, it was necessary to estimate the parameters of all the constructs that make up the model. Some items of the scales were removed in order to achieve more satisfactory adjustment measures. With these adjustments, it was achieved the indices presented in Table 1, that can be considered satisfactory.

The analysis of the general structural model (Figure 2) leads us to observe that the construct Social comparison has a strong impact on the degree of the adolescent (materialism β=0,75). Another construct that presented significant influence on materialism adolescent is the attraction of celebrities with β=0,31. Weakly, but significant, it can be emphasized the relation between gender and materialism (β=0.14) as well as the influence of the construct inverted self-esteem (β=-0.09), the inverted influence of the socioeconomic class (also with β=-0.09) and the influence of age with β=0,02. We cannot fail to mention the relationship between attitudes to the adverts and materialism adolescent with β=0,02.

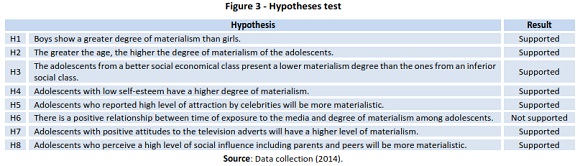

4.3 Hypotheses test

Figure 3 explains the hypotheses test. It should be emphasized that the eight assumptions made for the job, seven of them were supported by the proposed model. This suggests that the constructs proposed as antecedents of materialism adolescents are, in fact, influencers in behavior of this public as regards the relationship with their goods.

5. Discussion

From what was presented at the general structural model obtained, it is important to emphasize the following points. Firstly, it is worth pointing out that several constructs and variables were statistically significant to explain the materialistic behavior of the studied adolescents.

Regarding the variables researched, even with low intensity, the gender (β=-0,14) proved to be significant. That is, from, by the results, it is suggested that, in the sample surveyed, boys tend to be a little more materialistic than girls. In a previous study done by Micken (1995), the result obtained also had a negative correlation and a very low correlation in relation to gender. In the same perspective, another study done by Lins (2013) compared the materialism among Brazilian and Portuguese adolescents. The study pointed out that young boys attributed more importance to the materialistic values while young girls to religious values. Studies conducted by Achenreiner (1997), Churchill and Moschis (1979), Moore and Moschis (1981) with children and adolescents, also pointed out the male gender with higher materialistic score than women.

Regarding the age (β= 0,02), the data seem to say that, weakly, the greater the age, the higher the degree of materialism of the adolescent. This result is not coinciding with reports of some international studies cited by Churchill and Moschis (1979), Moore and Moschis (1981), Belk (1985), Richins and Dawson (1992), Dittmar and nd Denton (1994); Micken (1995) and Goldberg et al. (2003). In all these studies, the correlation found is a negative sense. Cameron (1977) still affirms that, as people get older, their materialistic thoughts tend to decrease. However, the Brazilian studies focused on children and adolescents conducted by Garcia (2009) performed in Brasilia and Santos and Souza (2013) implemented in Curitiba, revealed an index of materialism higher among children and young people in relation to adults.

The ‘economic class’ (β= -0,09), also showed statistically significant to influence the degree of materialism of the studied adolescents. This seems to lead to the observation that the adolescents of affluent classes tend to be more materialistic than the adolescents of less favored economic classes. Studies conducted by Rindfleisch et al. (1997) showed that individuals who come from families with higher income, have a tendency to be more materialistic, when compared to families with shorter material resources. Studies applied in young people by Richins and Dawson (1992) and Watson (2003) found no relationship between materialism and the economic class of the interviewees.

Another construct also tested in the model was the referring to ‘attitude to the adverts’ with a (β= 0,02) showed to be weakly significant materialistic to explain the behavior of adolescents.

In a moderate way with (β= 0.31), the construct 'attraction of celebrity’ seems to influence the degree of materialism of the studied adolescents. These results indicate that the higher the attraction of adolescents by celebrities, the greater it tends to be the degree of materialism of the respondents. In addition to awaken and maintain the attention of the public, celebrities also help with the increase of the rate remembrance of a propaganda, especially in a highly competitive market (Croft, Diane and Philip, 1996). In a study done by Lafferty and Goldsmith (1999), adolescents consumer has said that they are more likely to use products that are presented by celebrities. The use of celebrities in propaganda is justified exactly for their influence on the fan, stimulating the purchase of products, services and brands that they endorse (Tripp, Jensen & Carlson, 1994). Thus, individuals who worship celebrities tend to evaluate more positively products and brands endorsed by their idols (Rockwell & Giles, 2010.

The construct ‘self-esteem’ was inversely correlated with the adolescent materialism (β= -0,09). That is, adolescents with low self-esteem tend to have a higher degree of materialism, confirming the result with several other studies (Burroughs & Rindfleisch, 2002; Chaplin & John 2007; Kasser & Kasser, 2001; Munro Saunders, & Bore, 1998; Yurchisin & Johnson, 2004). The negative relationship between variables 'adolescent Materialism ' and 'Self-esteem' is justified by the fact that individuals with low self-esteem are in search of what can help them improve their image or how they feel (Chaplin & John, 2007).

The highlight of the model generated is the strong influence of the construct ‘social Comparison’ (β= 0,75) in the degree of materialism of the studied adolescents. In other words, the results suggest that both the ‘Communication with friends’ as the ‘Effect of peers’ has great influence on the degree of materialism of the adolescent. The social comparison is reinforced by the research made both in America (Richins, 2004), as in the east (Karabati & Cemalcilar, 2010) or in Europe (Shukla, 2008).

6. Conclusions

The contribution of work to the advancement of knowledge of the area is due to address a matter still little studied in the country - the materialism among adolescents - in an attempt to reduce the existing gaps in the literature on the subject. In addition, the survey results can encourage other researchers to develop complementary studies that can compose a body of knowledge capable of "mapping" this audience that, among other characteristics, offers a special complexity for being highly heterogeneous and mutant. Moreover, the theme materialism has adhesion to the various fields of marketing, including, in addition to the consumer behavior, areas such as marketing and society, culture and consumption among others.

It would not be reckless to affirm that the presented results seem to refer to the observation that the adolescent is a construction of meanings differentiated fruit of a lived experience built daily with the members of the family, with friends, colleagues, neighbors, media communications and other actors, articulated in a great circle of social interaction. Adherent to that was completed by Churchill and Moschis (1978), even in other cultural and social context, there is an influence of peers in the degree of materialism among adolescents, since that classmates, colleagues, friends and neighbors are important agents of socialization that contribute to a psychosocial development of the child and the adolescent.

In regard to the implications of the managerial study, it would be interesting to emphasize that companies generally tend to consider the adolescents either as children, or as adults in construction. It seems to be lacking on the part of the managers of marketing a greater concern in understanding this public from the perception as members of a social group which, as such, has distinct characteristics and contextually "tailored" on a day to day basis. The work adds to others that can provide if not tips for better attend this public at least the notion that is a category of consumers which can be better exploited.

Despite of the theoretical and methodological care, it must be recognized that this work presents some limitations. The first of them is related to the applied questionnaire that seems not to be capable of revealing complex and emotionally loaded information as the relationship of the adolescents with their goods. A second limitation arises from the fact of data collection to have been done by convenience. Another important issue which constitutes a work limitation has to do with the so-called social desirability bias. This concept can be understood as the result of answers assigned by the respondent that are not based on what he or she really believes or practice, but in which he or she perceives as being socially appropriate to reply.

This search does not end with these findings. With the objective to understand better the constructs studied, it is suggested as future research, with applications in individuals with inferior or superior age than the applied by this work. In addition, various other opportunities are relevant to scientific knowledge of consumer.

REFERENCES

Achenreiner, G. B. (1997). Materialistic values e susceptibility to influence in children. Provo: Association for Consumer Research. [ Links ]

Atkin, C. K. (1975). Survey of children’s and mothers’ responses to television commercials. The effects of television advertising on children. East Lansing: Eric Document Reproduction Service. [ Links ]

Bachmann, G., Deborah R. J., & Akshay R. (1993). Children’s Susceptibility to Peer Group Purchase Influence: an Exploratory Investigation. Provo: Association for Consumer Research. [ Links ]

Barbosa, L. & Campbell, C. (2006). Cultura, consumo e identidade. Rio de Janeiro: Editora FGV. [ Links ]

Banister E. N., & Hogg M. K. (2004). Negative symbolic consumption e consumers' drive for selfesteem: The case of the fashion industry. European Journal of Marketing, 38, 850-868. [ Links ]

Bearden W. O., & Etzel M. J. (1982). Reference Group Influence on Product and Brand Purchase Decisions. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(2), 183-194. [ Links ]

Belk, R. W. (1985). Materialism: Trait aspects of living in the material world. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(4), 265-280. [ Links ]

Berger, K. S. (2003). O desenvolvimento da pessoa: do nascimento a terceira idade.5 ed. Rio de Janeiro: Livros Técnicos Científicos. [ Links ]

Brechwald, W. A., & Prinstein, M. J. (2011). Beyond homophily: A decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 166-179. [ Links ]

Blascovich J., & Tomako J. (1991). Measures of self-esteem. In: J.P. Robinson, P.R. Shaver & L.S. Wrightsman, (Eds). Measures of personality e social psychological attitudes. (Vol 1, pp. 115-60). Academic Press. [ Links ]

Boon, S. D., & Lomore, C. D. (2001). Admirer celebrity relationships among young adults: Explaining perceptions of celebrity influence on identity. Human Communication Research, 27(3), 432-465. [ Links ]

Burroughs J. E., & Rindfleisch A. (2002). Materialism e well-being: A conflicting values perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 29(3), 348-370. [ Links ]

Buttle, F. (1992). Shop construct perspective. The Service Industries Journal, 12(3), 349-368. [ Links ]

Bybee, C., Robinson, J. D., & Turow, J. (1985). The effects of television on children: What the experts believe. Communication Research Reports, 2(1), 149-155. [ Links ]

Cameron, P. (1977). The life Cycle: Pespective and a Commentary. Oceanside: Dabor Science Publications. [ Links ]

Campbell, C. (1997). The shopping experience. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Carlson, L., Lacziniak, R. N., & Wertley, C. (2011). Parental Style: The implications of What We Know (and Think We Know). Journal of Advertising Research, 51(2), 427-435. [ Links ]

Chan K. (2005, September), Consumption of prestigious brands and source of influence among young people in Hong Kong. Media Digest, September, 14-15 (In Chinese). [ Links ]

Chan, K. (2013, January). Development of materialism values among children and adolescents. Young Consumers, 14(3), 244-257.

Chaplin, L. N., & John, D. R. (2007). Growing up in a material world: age differences in materialism in children e adolescents. Journal of Consume Research, 34(4), 480-493. [ Links ]

Childers T. L., & Rao A. R. (1992). A Influência da Família e dos pares com base na influência grupo de referência sobre as decisões do consumidor. Journal of Consume Research, 19(1), 198-211. [ Links ]

Churchill Jr. G. A., & Moschis, G. P. (1978). Consumer socialization: a theoretical e empirical analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 15(4), 599-609. [ Links ]

Churchill Jr. G. A., & Moschis, G. P. (1979). Television e interpersonal influences on adolescent consumer learning. Journal of Consumer Research, 6(1), 23-35. [ Links ]

Coopersmith, S. (1967). The antecedents of self-esteem. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman & Co. [ Links ]

Cramer D. (2003). Acceptance e need for approval as moderators of self-esteem e satisfaction with a romantic relationship or closest friendship. Journal of Psychology, 137(5), 495-505. [ Links ]

Croft R., Diane D., & Philip J.K. (1996). Word-of-Mouth Communication: Breath of Life or Kiss of Death? The Proceedings of the Martketing Education Group Conference. Glasgow: The Department of Marketing University of Strathclyde. [ Links ]

Darley, W. K. (1999). The relationship of antecedents of search e self-esteem to adolescent search effort and perceived product knowledge. Psychology & Marketing, 16(5), 409-27. [ Links ]

Dholakia, R. R. (1999). Going shopping: key determinants of shopping behaviors e motivations. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 27(4), 154-172. [ Links ]

Dittmar, H., Pepper, L. (1994). To have is to be: Materialism and person perception in working-class British adolescents. Journal of Economic Psychology, 15, 233-251. [ Links ]

Fernandes, D., & Santos, C. (2006). A Socialização de Consumo e a Formação do Materialismo entre os Adolescentes. Anais do Encontro Anual da Associação Nacional de Pós-graduação em Administração, Salvador, BA, Brasil.

Garcia, P. A. O. (2009). Escala Brasileira de Valores Materiais - EBVM. (Dissertação de Mestrado). Faculdade em Psicologia Social, do Trabalho e das Organizações, Universidade Federal de Goiás. Goiás, Brasil.

Goldberg, M. E., Gorn, G. J., Peracchio, L. A., & Bamossy, G. (2003). Understanding materialism among youth. Journal of Consumer Research, 13(3), 278-288. [ Links ]

Grohmann, M. Z, Battistella, L. F., Beuron, T. A., Riss, L. A., Carpes, A. M., & Lutz, C. (2011). Relação entre materialismo e estilo de consumo: homens e mulheres com comportamento díspare? Revista Contaduría y Administración, 57(1), 185-214. [ Links ]

Gu, F. F., & Hung, K. (2009). Materialism among adolescents in China: a historical generation perspective. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 3(2), 56-64. [ Links ]

Hair F. J., Black W. C., Babin, B. Anderson, R. E., & Tathan, R. L. (2009). Análise multivariada de dados, Ed. 6. Porto Alegre: Bookman.

IDP (2013). Instituto Data Popular. Acesso em 10 de Junho, 2014, de http://www.datapopular.com.br/na-imprensa/ [ Links ]

Jindal-Snape, D., & Miller, D. (2008). A challenge of living? Understanding the psycho-social processes of the child during primary-secondary transition through resilience e self-esteem theories. Educational Psychology Review, 20(3), 217-36. [ Links ]

John, D. R. (1999). Consumer Socialization of Children: A Retrospective Look at Twenty-Five Years of Research. Journal of Consumer Research, 26(1), 183-213. [ Links ]

Kahle, L. R., & Homer, P. M. (1985). Physical Attractiveness of the Celebrity Endorser: A Social Adaptation Perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 11(4), 954-961. [ Links ]

Karabati, S., & Cemalcilar, Z. (2010). Values, materialism, and well-being. A study with Turkish university students. Journal of Economic Psychology, 31(4), 624-633. [ Links ]

Kasser, T., & Kasser, V. G. (2001). The dreams of people high and low in materialism. Journal of Economic Psychology, 22(6), 693-719. [ Links ]

Kwak, H., Zinkhan, G. M., & Dominik J. R. (2002). The moderating role of gender e compulsive-buying tendencies in the cultivation effects of TV show e TV advertising: A cross cultural study between the United States e South Korea. Media Psychology, 4(1), 77-101. [ Links ]

Kwan C. W. (2013). The Relationship between Advertising and the level of Materialism among Adolescents in Hong Kong. SS Student E-Journal, 2(1), 68-69. [ Links ]

Lachance M. J., Beaudion P., & Robitaille J. (2003). Adolescents Brand Sensitivity in Apparel: Influence of Social Agents. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 27, 47-57. [ Links ]

Lafferty, B. A., & Goldsmith, R. E (1999). Corporate Creditability´s role in consumers’ attitudes and purchase intentions when a high versus a low creditability endorser is used in the ad. Journal of Business Research, 4(2), 109-116. [ Links ]

Larsen, M., Joseph Sirgy, & Newell D. Wright (1999). Materialism: The Construct, Measures, Antecedents, and Consequences. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 3(2), 75 - 107.

Lins, S. L. B. (2013). Consumo, contexto socioeconômico e compra por impulso em adolescentes brasileiros e portugueses. (Tese de Doutorado). Faculdade de Psicologia e Ciências da Educação, Universidade do Porto. Portugal.

Malhotra, N. (2006). Pesquisa de marketing: uma orientação aplicada. 4º Edição. Porto Alegre: Bookman. [ Links ]

Mangleburg, T., Doney, P., & Bristol, T. (2004). Shopping with friends and teens’ susceptibility to peer influence. Journal of Retailing, 80(2), 101-116. [ Links ]

Martin, C. A., & Bush, A. J. (2000). Do role models influence teenagers purchase intentions e behavour? Journal of Consumer Marketing, 17(5), 441-454. [ Links ]

McCracken, G. (2003). Cultura e consumo. Rio de Janeiro: Mauad. [ Links ]

Micken, K. S. (1995). A New Appraisal of the BELK Materialism Scale. Advances in Consumer Research, 22(1), 398-405. [ Links ]

Miller, D. A. (1998). Theory of Shopping. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. [ Links ]

Moschis, G .P. & Mitchell, R. L. (1986). Television advertising and interpersonal influence on teenager's participation in family consumer decisions. Advances In Consumer Research, 13(1), 181-186. [ Links ]

Moore, R. L., & Moschis, G. P. (1978). Teenagers’ reactions to advertising. Journal of Advertising, 7(4), 24-30. [ Links ]

Moore, R. L., & Moschis, G.P. (1981). The role of family communication in consumer learning. Journal of Communication, 31(4), 42-51. [ Links ]

Moschis, G. P. & Moore, R. L. (1982). A longitudinal study of television advertising effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 9, 279-286. [ Links ]

Moschis, G. P. (1985). The role of family communication in consumer learning. Journal of Communication, 11(4), 898-913. [ Links ]

Moschis, G. P. (1987). Consumer socialization: a life cycle perspective. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, Inc.

Moschis, G. P., Moore, R. L., & Stanley, T. J. (1984). An exploratory study of brand loyalty development. Advances in Consumer Research, 11(1). [ Links ]

Moura, A. G. (2005). Impacto dos Diferentes Níveis de Materialismo na Atitude ao Endividamento e no Nível de Dívida para Financiamento do Consumo nas Famílias de Baixa Renda do Município de São Paulo. (Dissertação de Mestrado). Faculdade em Administração de Empresas, Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo da Fundação Getulio Vargas. São Paulo: Brasil.

Moura, A. G., Aranha, F., Zambaldi, F., & Ponchio, M. C. (2006). As Relações entre Materialismo, Atitude ao Endividamento, Vulnerabilidade Social e Contratação de Dívida para Consumo: um estudo empírico envolvendo famílias de baixa renda no município de São Paulo. In: Anais. Rio de Janeiro: EMA. [ Links ]

Opree, S. J., Buijzen, M., & Van Reijmersdal, E. A. (2013). Measuring children’s advertising exposure: A comparison of methods and measurements. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association. London, UK. [ Links ]

Ponchio, M. C., Aranha, F., & Todd, S. (2006). Estudo exploratório do construto de materialismo no contexto de consumidores de baixa renda do Município de São Paulo. In: Anais da ANPAD (pp. 1-16). Rio de Janeiro: ANPAD. [ Links ]

Ponchio, M., & Aranha, F. (2007). Necessidades, vontades e desejos: a influência do materialismo sobre a dívida de consumo dos paulistanos de baixa renda. In: Anais da ANPAD. Rio de Janeiro: ANPAD. [ Links ]

Richins, M. L., & Dawson, S. (1992). A Consumer values orientation for materialism e its measurement: scale development e validation. Journal of Consumer Research, Chicago, 19(3), 303-316. [ Links ]

Richins, M. L. (2004). The material values scale: measurement properties e development of a short form. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(1), 209-219. [ Links ]

Riesman, D., Glazer, N., & Denny, R. (1950). The lonely crowd. New Haven. (Ed. 1). Yale: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Rindfleisch, A, Burroughs, E. J. and Frank Denton (1997), Family structure, materialism and compulsive consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 23(4), 312-325.

Rockwell, D., & Giles, D. C. (2010). Being a celebrity: a phenomenology of fame. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 40(2), 178-210. [ Links ]

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society e the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Santos, T., & Souza, M. J. B. (2012). Materialismo entre crianças e adolescentes: o comportamento do consumidor infantil de Santa Catarina. In: Anais EMA, 5. Curitiba-PR: EMA.

Saunders, S., Munro, D., & Bore, M. (1998). Maslow´s hierarchy of needs and its relationship with psychological health and materialism. South Pacific Journal of Psychology, 10(2), 15-25. [ Links ]

Scaraboto, D., Zilles, F. P., & Rodriguez, J. (2005). Relacionando conceitos sob perspectiva cultural: comparar consumo de luxo e materialismo? In: Anais, 29, Brasília. [ Links ]

Shukla, P. (2008). Conspicuous consumption among middle age consumers: psychological and brand antecedents. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 17(1), 25-36. [ Links ]

Smith, S. K., & Roy, A. (2008). The interrelationship between television viewing, values e perceived well-being: a global perspective. Journal of International Business Studies 39(1), 1197-1219. [ Links ]

Tripp, C., Jensen, C., & Carlson, L. (1994). The effects of multiple product endorsements by celebrities on consumers’ attitudes and intentions. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(4), 535-547. [ Links ]

Ward, S., & Wackman, D. (1971). Family e media influences on adolescent consumer learning. American Behavioral Scientist, 14(1), 415-427. [ Links ]

Ward, S. (1974). Consumer socialization. Journal of Consumer Research, 1(1), 1-14. [ Links ]

Watson, J. J. (1998). Materialism e debt: a study of current attitudes e behaviors. Advances in Consumer Research, 25(1), 203-207. [ Links ]

Watson, J. J. (2003). The relationship of materialism to spending tendencies, saving, and debt. Journal of Economic Psychology, 24(6), 723-739. [ Links ]

Yoh T. (2005). Parent, Peer and TV Influences on Teen Athletic Shoe Purchasing.Recuperado de www.academicjournals.org/journal/AJBM/article-full-text-pdf/2A772BA21009. [ Links ]

Yurchisin, J., & Johnson K. K. P. (2004). Compulsive buying behavior and its relationship to perceived social status associated with buying, materialism, self-esteem, and apparel-product involvement. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 32(3), 291-314. [ Links ]

Received: 55 May 2016

Accepted: 4 October 2016