Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.13 no.2 Faro jun. 2017

MANAGEMENT: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Knowledge internalization as a measure of results for organizational knowledge transfer: proposition of a theoretical framework

Internalização do conhecimento como medida de resultados da transferência de conhecimento organizacional: a proposição de um framework teórico

*Helen Aquino, ** José Márcio de Castro

*Fundação Ezequiel Dias Rua Conde Pereira Carneiro, nº 80, Bairro Gameleira, Cep: 30510-010, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil. helen.aquino@funed.mg.gov.br

**Pontifical Catholic University of Minas Gerais, Departament of Business Administration, Av. Itaú, nº 525, Bairro Dom Cabral, Cep: 30535-012, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil, josemarcio@pucminas.br

ABSTRACT

As this is result of the transfer of knowledge, most studies on this subject have considered the implementation of organizational knowledge as a positive result and as the end of the transfer process; internalization as active adoption of knowledge has seldom been investigated. This is assuming that it is only when knowledge is internalized by the recipient company that the transfer process really becomes effective and incorporated into organizational routine. The aim of this paper is propose a theoretical framework using internalization as the variable to analyze the effectiveness of the knowledge transfer process. For this, a comprehensive literature review was conducted that resulted in the identification of important variables that moderate the internalization: the disseminative capacity and the absorptive capacity. Moreover, this article proposes an analysis of internalization from a multidimensional perspective, considering the appropriation of knowledge and time taken to internalize as extension factors of knowledge internalization.

Keywords: Knowledge transfer, knowledge internalization, absorptive capacity, disseminative capacity.

RESUMO

Tratando-se de resultado da transferência de conhecimento, grande parte dos estudos sobre o tema tem considerado a implementação do conhecimento organizacional como um resultado positivo e como o final do processo de transferência, sendo que a internalização enquanto adoção ativa do conhecimento tem sido pouco investigada. Partindo da premissa de que, somente quando o conhecimento é internalizado pela empresa receptora, o processo de transferência torna-se realmente efetivo e incorporado na rotina organizacional. O objetivo desse artigo é propor um framework teórico utilizando a internalização como variável para analisar a efetividade do processo de transferência de conhecimento. Para tal, foi realizada uma ampla revisão da literatura que resultou na identificação de importantes variáveis que moderam a internalização: a capacidade disseminativa e a capacidade absortiva. Além disso, esse artigo propõe uma análise da internalização sob uma perspectiva multidimensional, considerando a apropriação do conhecimento e o tempo de internalização como fatores de extensão da internalização do conhecimento.

Palavras-chave: Transferência de conhecimento, internalização do conhecimento, capacidade absortiva, capacidade disseminativa.

1. Introduction

Several studies indicate that organizations can gain competitive advantage and maximize their innovative capacity by learning from one another´s experience through knowledge transfer (e.g., Easterby-Smith, Lyles, & Tsang, 2008; Pérez-Nordtvedt, Kedia, Datta, & Rsheed, 2008; Szulanski, 1996; Szulanski, 2000; Szulanksi, Ringov, & Jensen, 2016). In this context, knowledge transfer has become relevant to the success of organizations (Lane, Salk & Lyles, 2001; Pérez-Nordtvedt et al., 2008; Van Wijk, Jansen, & Lyles, 2008), and has become an important research area within organizational learning and knowledge management (Easterby-Smith et al., 2008). The knowledge transfer process can be understood broadly as the merger of shares and recreation of new knowledge in the receiver´s company environment (Szulanski, 1996). Although the existence of a range of studies using the lens of knowledge transfer can be observed (Becerra, Lunnan, & Huemer, 2008; Easterby-Smith et al., 2008; Pérez-Nordtvedt et al., 2008; Van Wijk et al., 2008), far fewer studies are devoted to the results of the transfer (Van Wijk et al., 2008). Most research is dedicated only to the analysis of the implementation of the transfer. In other words, it is still very early in the research into the active adoption of transferred knowledge, that is, studies that take internalization as a measure of the effective result of a knowledge transfer process (Kostova, 1999; Kostova & Roth, 2002; Penna & Castro, 2015).

Knowledge internalization as an indicator of results in knowledge transfer assumes that the receiving company combines existing internal knowledge with the external knowledge acquired through the transfer, and starts to use it in its daily activities (Kostova & Roth, 2002). The literature (Kostova & Roth, 2002) defines internalization as the "state in which the employees at the recipient unit view the practice as valuable for the unit and become committed to the practice” (p. 217). For Kostova (1999), the effective result of knowledge transfer is possible when knowledge is internalized. It is from knowledge internalization that the recipient develops an ability to apply the knowledge transferred to real situations (Tsai & Lee, 2006), better responding to internal and market needs. To Kostova and Roth (2002), internalization "facilitates not only the initial adoption of the practice, but also its persistence and stability over time" (p. 217).

In this aspect, if knowledge internalization is used as a measure of results in the complex and difficult knowledge transfer process, some important factors that can interfere with the effectiveness of this process must be taken into consideration. Among these variables, some emerge with more emphasis in the literature: disseminative capacity (Becerra et al., 2008; Cabrera & Cabrera, 2005; Minbaeva & Michailova, 2004; Pérez-Nordtvedt et al., 2008; Szulanski & Cappetta, 2003; Tang, Mu, & MacLachlan, 2010), and absorptive capacity (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Jansen, Van Den Bosch, & Volberda, 2005; Van Den Bosch, Van Wijk, & Volberda, 2003; Vega-Jurado, Gutièrrez-Gracia, & Fernándes-de-Lucio, 2008; Zahra & George, 2000).

Starting from the premise that an effective knowledge transfer process only occurs when the knowledge transferred by the sender is internalized by the receiver company, and with the view that studies that consider internalization as an effective outcome of the complex process of knowledge transfer are still incipient, a comprehensive review of the literature on the subject must take place. The aim of this paper is to propose a theoretical framework aimed at reflecting on the knowledge internalization transfer of organizational knowledge, and to identify variables relevant to the study of knowledge transfer, and the extent that may affect the outcome of the transfer process.

In addition, the literature on knowledge internalization has emphasized a one-dimensional perspective in the analysis of the factors influencing the process of internalization. Thus, several authors consider the internalization of knowledge as a variable that reflects the effectiveness of the knowledge transfer process without, however, further investigating the extent of internalization (see, for example, Penna & Castro, 2015; Cummings, 2003; Kostova, 1999). In this sense, this proposal extends and advances the discussions on the issue, proposing a new perspective on the extension of the process of internalization of knowledge as function of the appropriation of knowledge and the time taken for knowledge internalization by the recipient.

2. Literature Review

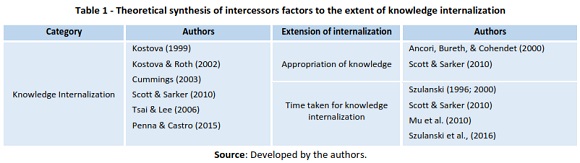

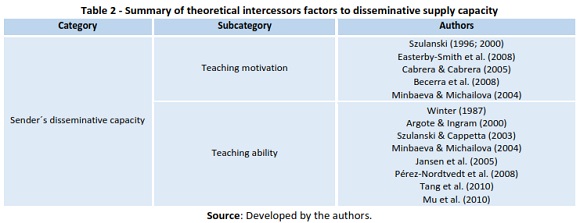

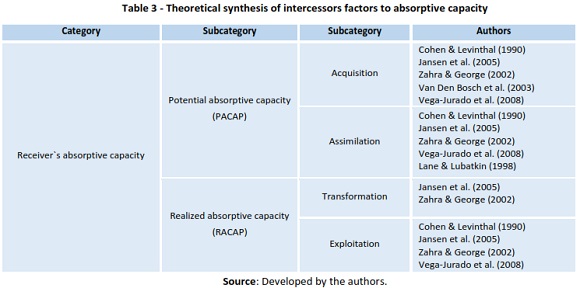

In this section, we present a review of the literature on knowledge internalization, and provide the appropriation of knowledge and the time taken for knowledge internalization as extension factors of knowledge internalization. Then we discuss how disseminative capacity and absorptive capacity can moderate knowledge internalization.

2.1 Knowledge internalization as an outcome measure of the knowledge transfer process

In a turbulent business environment, the acquisition of knowledge has been part of the strategy of many organizations that need to acquire external knowledge to improve their performance and survive (Argote & Ingram, 2000; Pérez-Nordtvedt et al., 2008; Van Wijk et al., 2008). The transfer of knowledge is understood as an "(...) event through which one organization learns from the experience of another" (Easterby-Smith et al., 2008, p. 677). However, knowledge transfer is not a simple process, and the result cannot be taken for granted (Szulanski, 1996), since several factors can interfere with the effectiveness of the final result.

One of the critical points in the knowledge transfer process refers to the difficulty of evidencing if learning has occurred, that is, the successful transfer can be defined as the degree to which knowledge is recreated at the receiver end (Cummings, 2003). However, several authors point out that it is a challenge to measure this result (Easterby-Smith et al., 2008; Pérez-Nordtvedt et al., 2008; Sammarra & Biggiero, 2008; Van Wijk et al., 2008). Thus, in relation to the results of knowledge transfer, there are several studies in the literature that, in general, relegate the possession or the implementation of knowledge transfer as a measure of this process (Cummings, 2003; Pérez-Nordtvedt et al., 2008; Scott & Sarker, 2010). However, knowledge implemented is not always synonymous with internalized knowledge: "only the possession of knowledge does not guarantee a competitive advantage" (Mu et al., 2010, p. 31).

The work of Kostova and Roth (2002) which measures internalization as the active adoption of knowledge, when transferred practice becomes incorporated in the receiver as valued, not simply adopted formally. In these terms, Kostova and Roth (2002) point out that the implementation and internalization of knowledge are different adoptions of depth dimensions in practiced knowledge by the receiver. For Kostova and Roth (2002) implementation occurs even when the receiving company adopts the practice but does not see it as valuable and does not assign meaning to it. This adoption can occur because of strong regulatory institutional pressure. Yih-Tong Sun and Scott (2005) emphasize that organizations often experience significant pressure to adopt, modify or abandon some of their practices and these pressures may come from a variety of sources. In this aspect, when the receiver takes a practice with which it is not identified and to which value is not assigned, this is ceremonial adoption, where a high level of implementation is accompanied by a low level of internalization and thus an incomplete transfer process (Kostova & Roth, 2002).

On the other hand, when the receiver attaches practical sense, it becomes engaged with it and internalizes it, changing its original behavior. That is, the external knowledge is absorbed into internal knowledge bases and is now applied in the organizational routine, effectively becoming incorporated into the receiving behavior (Chappin, Cambre, Vermeulen, & Lozano, 2015; Kostova & Roth, 2002).

To Kostova and Roth (2002), knowledge transfer becomes a complete process when the receiving company not only implements, but also internalizes practical knowledge or transfer, characterized thus as active adoption. Thus, Kostova (1999) argues that implementation is a necessary condition for internalization, but "(...) implementation does not automatically result in the internalization" (p. 311).

2.1.1 The appropriation of knowledge and the time taken for knowledge transfer as extension factors for knowledge internalization

To understand the internalization as a result of knowledge transfer it is important to assess not only knowledge implementation, but also to analyze the extent of the appropriation of this knowledge by the receiver. Knowledge internalization is first related to the ability to see value in the transferred knowledge, that is, to understand the knowledge as something efficient and useful for organizational routine; to see the knowledge as valuable is the premise for motivation to learn and then appropriate knowledge. Otherwise, what we see is a ceremonial or formal adoption (Kostova & Roth, 2002), as previously.

Since the knowledge is seen as valuable, appropriate and relevant to the interests, needs and the reality of the receiving company, the highest level is ownership of the transferred knowledge, that is, a greater identification with the new knowledge. Thus, the external knowledge becomes own knowledge. Several authors (e.g., Araújo, Duarte, & Castro, 2015; Szulanski, 1996) highlight the difficulty and reluctance of some receivers to accept external knowledge they do not consider as their own and do not identify with: the ‘not invented here' syndrome. The identification between sender and receiver can reduce the effects of this syndrome and the feeling of the ‘strangeness' of transferred practices (Araújo et al., 2015), which will contribute to the extent of the internalization of practices (Kostova & Roth, 2002).

Once the transferred knowledge is appropriated by the receiving company, the organization achieves better, more lasting and more authentic results. From this perspective, the internalization maximizes the benefits of knowledge transfer (Mu et al., 2010). In this sense, Ancori, Bueth, and Cohendet (2000) define the ownership of knowledge as the result of the reengineering process of knowledge, that is, the combination of existing knowledge with new knowledge, not just the result of the transmission from the source of knowledge to the recipient. Thus, we must consider that this process of reengineering - ownership - of knowledge, rather than a mere act of transmission and reception, takes time to be incorporated and internalized in the receiver's organizational routine.

Therefore, another important aspect to be considered about knowledge internalization relates to the time taken for internalization. Although some studies deal with knowledge transfer as an automatic snapshot process, what is observed is that the transfer is often complex, laborious, difficult, and time-consuming (see, for example, Easterby-Smith et al., 2008; Pérez-Nordtvedt et al., 2008; Szulanski, 2000), requiring time to be successful. In this sense, the overall process of knowledge transfer consists of multiple phases that incur effort, costs, and uncertainties and mainly takes time (Szulanski et al., 2016).

The argument is that the knowledge transfer process cannot be reduced to the mere implementation of the practice by the receiver, but the internalization of this knowledge (Kostova & Roth, 2002), which certainly takes time. When a receiver initiates the use of transferred knowledge, unexpected problems begin to emerge caused by the combination of new knowledge with the existing routine. For Szulanski (2000), it takes time for employees to be sufficiently trained and prepared to perform the new roles, since the internalization of new practices involves significant changes in the system of language and interpretation of the new policies, which happens over time.

Thus, people must first unlearn to do what has been done to then replace the old knowledge with the new (Hamel, 1991). This process of unlearning takes time. Such efforts to ‘forget' prior knowledge can only be successful after the new knowledge is put to use and tends to decrease as the receiver gets, over time, satisfactory results with the use of the new knowledge (Szulanski, 2000). In specific situations, the transferred knowledge becomes adopted and generates satisfactory results, which further contributes to the internalization of knowledge. Time, in this case, seems to be the ‘master of reason' so that the new knowledge is incorporated and transformed into pre-existing routines and starts to generate positive results, which contributes to the internalization process.

However, internalization can be more or less extensive, and take more or less time and these variations are related to factors that could adversely or positively affect the process. Among these factors, we highlight disseminative capacity (Cabrera & Cabrera, 2005; Pérez-Nordtvedt et al., 2008; Tang et al., 2010) and absorptive capacity (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Lane, Koka, & Pathak, 2006; Zahra & George, 2002).

Zahra and George (2002) consider absorptive capacity as a multidimensional construct consisting of a set of routines and organizational processes. The degree of absorptive capacity of the receiver depends on multiple factors, including past experience of the company, complementary knowledge and diverse sources of knowledge, and is also related to basic knowledge and business skills (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). In this sense, companies that have a higher absorptive capacity have a greater stock of knowledge (Knoppen, Sáenz, & Johnston, 2011), and probably need less time for internalization (Szulanski, 1996; Szulanski et al., 2016), as the accumulation of knowledge allows the most efficient use of the transferred knowledge (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990).

On the other hand, disseminative capacity can also influence the time needed for knowledge internalization by the receiver. The ability to transfer reflects the ability of the source to teach in a clear and didactic manner the knowledge to be transferred (Minbaeva & Michailova, 2004; Winter, 1987). Thus, when the source has a high disseminative capacity, knowledge is more easily understood and articulated by the receiver, which contributes to the internalization process. When the source of knowledge does not have adequate capacity to transfer knowledge, the process will be marked by different interpretations of the same idea, needing many beginnings and many interruptions (Mu et al., 2010) demanding thus more time for internalization. Table 1 shows the theoretical summary of this session.

2.2 Disseminative capacity and knowledge internalization

The literature (see, for example, Argote & Ingram, 2000; Easterby-Smith et al., 2008; Szulanski, 1996; Szulanski 2000; Minbaeva & Michailova, 2004) presents disseminative capacity, which includes teaching motivation (Easterby-Smith et al., 2008; Minbaeva & Michailova, 2004), and the ability to transfer knowledge (Argote & Ingram, 2000; Yih-Tong Sun & Scott, 2005), as one of the most important factors for successful internalization. The receiver's absorptive capacity is not enough for a positive result of the internalization of knowledge if the source does not have the characteristics necessary for clear and efficient knowledge transfer (Easterby-Smith et al., 2008).

However, disseminative capacity can either facilitate or become an obstacle to the knowledge transfer process, and thus impair internalization. It is an essential variable in order that it is the sender that starts the knowledge transfer process. The disseminative capacity can be defined as "the ability of knowledge holders to transfer knowledge efficiently, effectively and convincingly so that other people can accurately understand and put their learning into practice" (Tang et al., 2010, p. 1587).

First of all, it is necessary for the sender to be willing to transfer knowledge (Becerra et al., 2008; Easterby-Smith et al., 2008; Minbaeva & Michailova, 2004; Szulanski, 1996; Szulanski 2000). The sender´s motivation to transfer knowledge is essential to start the process, as a company that is not willing to share their knowledge makes the relationship difficult and generates no enthusiasm in the receiver (Becerra et al., 2008; Cabrera & Cabrera, 2005; Easterby-Smith et al., 2008).

For there to be no sender fear and for the process to run smoothly, generating satisfactory results, there must be a trusting relationship between the sender and the receiver (Becerra et al., 2008; Easterby-Smith et al., 2008). Assuming that knowledge is one of the most important and strategic resources of an organization (Becerra et al., 2008), the trust relationship between the sender and the receiver is closely related to the target that will be given to the transferred knowledge (Easterby -Smith et al., 2008). Being concerned of what will be done with the transferred knowledge is one of the biggest concerns of enterprises who are senders of knowledge. As a knowledge transfer may be used for purposes not intended or are incorrect (Easterby-Smith et al., 2008), that which was previously a situation of strategic alliance and cooperation between enterprises can become a market competition. These situations may occur in the cases of strategic alliances or networks where companies are structured through joint ventures, R & D coalitions, franchising, etc., and are ‘forced' to share their knowledge (Becerra et al., 2008; Kostova & Roth, 2002). Thus, there is an external pressure for the transfer to be made (Araújo et al., 2015). If trust is not consolidated between the donor and the recipient, the tension between companies can jeopardize whole success of knowledge internalization.

Organizations may even be well-meaning and willing to transfer their knowledge, however, they cannot succeed if they do not know how to act. It is necessary that the knowledge sender has the ability to transfer (Argote & Ingram, 2000; Jansen et al., 2005; Minbaeva & Michailova, 2004; Pérez-Nordtvedt et al., 2008; Szulanski & Cappetta, 2003; Winter, 1987). This requires that the sender has characteristics necessary to know how to teach (Minbaeva & Michailova, 2004; Noblet & Simon, 2012; Tang et al., 2010), or how to transmit their knowledge clearly and efficiently.

The ability to transfer knowledge is related to the presence of adequate resources to facilitate the process. These resources include both the presence of qualified people to teach, as appropriate technological resources, and appropriate transfer mechanisms (Yih-Tong Sun & Scott, 2005; Szulanski et al., 2016). Disseminative capacity implies education (Winter, 1987), deep technical knowledge and social skills to communicate, articulate and translate knowledge into the language and reality of the receiver, and this can mitigate misunderstandings and deficiencies in interpretation and accelerate the internalization of transferred knowledge, making the process faster and successful (Mu et al., 2010).

When the sender lacks competence in teaching, the knowledge receiver may have different interpretations of the same idea and the transferred knowledge can be distorted. In addition, the transfer may be marked by several interruptions in the process, gaps and false starts (Mu et al., 2010). This can occur because the ability of senders to interpret and communicate the knowledge transferred has a significant impact on the learning processes of knowledge receivers. Mu et al. (2010) illustrate this capability contrast; for example, the teacher who can teach in a way that even lay people can understand, and the teacher who can confuse even the most advanced students.

Minbaeva and Michailova (2004) argue that, generally, knowledge valuable enough to be transferred is in the form of tacit knowledge, difficult to codify, and needs more work to be internalized. In this case, the source needs to have a well-developed ability to translate and decode knowledge so that this is understood, absorbed and used by the receiver. This ability to transfer knowledge can be developed through training or experience by employees of the sending company, participating in trips to work with receiving employees, working through on site the difficulties that arise in the transfer process and helping them to solve problems that arise in practice. Participating in these various experiments, the sender enhances its disseminative capacity and becomes a great teacher (Minbaeva & Michailova, 2004). Thus, a high knowledge disseminating capacity can contribute to the success of the process, that is, the internalization of knowledge transferred from the receiver. Table 2 shows the theoretical summary of this session.

2.3 Absorptive capacity and knowledge internalization

Absorptive capacity (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Zahra & George, 2002), is presented as one of the most influential factors in knowledge transfer, often being associated with the success of knowledge transfer (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Scott & Sarker, 2010; Szulanski, 2000). Absorptive capacity is understood as the ability to recognize the value of external knowledge, and to assimilate, explore and use new knowledge (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Zahra & George, 2002).

Cohen and Levinthal (1990) propose the premise that previous knowledge facilitates the learning of new knowledge. In this sense, absorptive capacity is influenced by the experiences of the receiver, the organizational culture and the ability to retain newly acquired knowledge (Lane & Lubatkin, 1998). Therefore, it is possible to suggest that a larger capacity to receive knowledge positively influences the result of the knowledge transfer process.

Zahra and George (2002) conducted a review, reconceptualization and extension of the Cohen and Levinthal (1990) model and proposed that absorptive capacity should be defined as a dynamic capability, that is, a set of routines and organizational processes that enables companies to acquire, assimilate, transform, and exploit knowledge. The authors divide these dimensions into potential absorptive capacity (PACAP) and realized absorptive capacity (RACAP). The potential capacity provides the basis for the receiver to acquire and absorb external knowledge (Lane & Lubatkin, 1998). However, only having PACAP does not guarantee the use of this knowledge. For knowledge transfer to be complete, it is necessary that the organization also has RACAP, which covers the processes of transformation and exploitation and reflects the ability of companies to leverage the knowledge that has been absorbed (Jansen et al., 2005).

What the literature shows is that both the ability of employees (the knowledge base) and their motivation (intensity of effort) are factors of essential importance to internalization. In this sense, Minbaeva, Pedersen, Bjöjkman, Fey, and Park (2003) relate a high degree of skill of the employees from the company to PACAP, while RACAP is related to a high degree of employee motivation. For these authors, the interaction between the ability and motivation of employees increases the internalization level of transferred knowledge.

To understand how absorptive capacity can influence internalization, it is important to understand the four dimensions of absorptive capacity (Zahra & George, 2002). The first dimension of absorptive capacity refers to the organization's ability to take advantage of received valuable knowledge. For this, besides the ability to see value in knowledge, it is essential that the recipient knows how to act in transfer opportunities to acquire new knowledge. This dimension is enhanced when the receiver has a high level of qualifications in its work force and significant volumes of spending on R & D (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Jansen et al., 2005; Penna & Castro, 2015; Van Den Bosch et al., 2003; Vega-Jurado et al., 2008).

The dimension of assimilation proposed by Zahra and George (2002) also relates to PACAP, referring to the capacity of the receiver to analyze, process, interpret, and understand knowledge gained from external sources. When the receiver has the ability to convert and translate the external knowledge to the inner reality of the organization, it facilitates learning (Zahra & George, 2002) and thus contributes to the knowledge internalization.

However, as presented by Zahra and George (2002), only having PACAP does not necessarily imply a better performance by the company. Just as companies cannot exploit the knowledge before they acquire it, they need to be able to apply the new knowledge to generate innovation, which requires the receiving company to have RACAP (Zahra & George, 2002).

The first movement of RACAP refers to the transformation effort of knowledge. Put another way, it is the recipient's ability to develop and refine the routines that facilitate the combination of existing knowledge with new knowledge acquired and assimilated (Jansen et al., 2005). For Szulanski (1996), the absorptive capacity of the receiving company contributes to the ‘old practices' being discarded and new ones built.

Finally, the application refers to the receiving company's ability to use the transferred knowledge, that is, the ability of receiver to incorporate the knowledge acquired, assimilated and transformed into its operations and organizational routines for application and use (Jansen et al., 2005, Vega-Jurado et al., 2008). A successful knowledge transfer requires not only that the receiver has absorbed new knowledge, but also that the company is able to apply it effectively (Scott & Sarker, 2010). Therefore, if the company is successful in absorbing external knowledge, it should also be well equipped to spread knowledge within its organizational boundaries (Easterby-Smith et al., 2008) and thereby achieve knowledge internalization.

Together, the four dimensions of absorptive capacity (Table 3) enable companies to explore new discoveries and knowledge and act as a crucial intangible ability to increase the internalization of transferred knowledge (Zahra & George, 2002).

3. Proposition Framework

3.1 Dependent variable

Assuming that the result of knowledge transfer is effective when transferred practices are internalized by the receiving company (Cummings, 2003; Kostova, 1999; Kostova & Roth, 2002; Penna & Castro, 2015), in other words, when the receiver changes its original behavior, and use of new knowledge becomes part of the organizational routine, knowledge internalization is the dependent variable of the theoretical framework presented below.

In this sense, the present study suggests that knowledge internalization should be considered as a multidimensional variable, where other aspects should be taken into account in assessing the extent of the results of the organizational practices transfer process. Thus, this study suggests that knowledge internalization is evaluated based on the extent of the appropriation of knowledge by the receiver and the time taken for knowledge internalization. From the literature review, we believe that these two dimensions are key aspects for a complete understanding of knowledge internalization as an effective result of the knowledge transfer process.

3.2 Independent variables

Disseminative capacity is one of the factors that interferes with the results of knowledge internalization. At the same time, the sender company needs to be motivated to offer something of value, and have the ability to transfer knowledge efficiently (Easterby-Smith et al., 2008). In the absence of motivation and ability to transfer, the success of internalization can be compromised.

Similarly, if the sender is very willing to share tacit and explicit knowledge, with the assurance that the receiver will use this knowledge as agreed (Easterby-Smith et al., 2008) and it has a great ability to teach what it knows, the time for knowledge internalization by the receiver will be reduced. From this discussion, we formulate the following proposition.

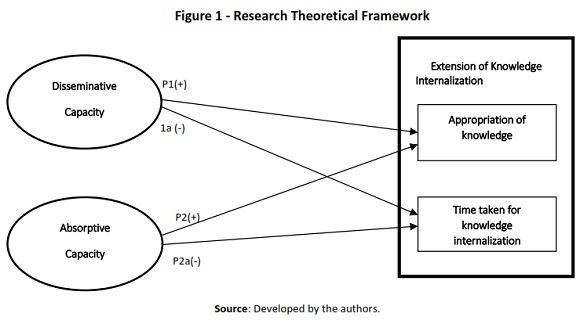

P1: A greater disseminative capacity contributes to greater knowledge appropriation by the receiver.

P1a: A greater disseminative capacity reduces the time taken for knowledge internalization by the receiver.

However, a high disseminative capacity is not sufficient to ensure the internalization of the transferred knowledge. The receiver´s absorptive capacity is another essential factor for successful internalization. To this end, it is necessary that the receiver is able to acquire, assimilate, transform, and use the new knowledge (Zahra & George, 2002).

Furthermore, it is proposed that knowledge internalization is not automatic, it is a complex process that requires time to reach maturity. In this sense, the greater the absorptive capacity of the receiver, the better the recognition capability, level of acceptance, and the ability to make the necessary connections between old and new knowledge. Thus, the absorptive capacity influences the time taken for organizational practice internalization. From this discussion, we formulate the following proposition:

P2: A greater absorptive capacity contributes to a greater knowledge appropriation by the receiver.

P2a: A greater absorptive capacity reduces the time taken for knowledge internalization by the receiver.

The theoretical model below (Figure 1) shows the relations proposed:

4. Discussion

In this paper we explore the concept that knowledge internalization can represent an effective result of organizational knowledge transfer. Taking into consideration that knowledge internalization is not an event but a complex process, where a number of factors can affect the effectiveness of internalization, two main variables in this process emerge with greater emphasis in the literature: disseminative capacity (Easterby-Smith et al., 2008; Minbaeva & Michailova, 2004; Szulanski, 1996) and absorptive capacity (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Zahra & George, 2002; Jansen et al., 2005). Often studied separately in the literature, disseminative capacity and absorptive capacity should be analyzed together whenever possible, in order that internalization is a dual loop process (Mu et al., 2010), in which both may compromise the effectiveness of the transfer. For managers and organizations that participate in knowledge transfer processes, this implies the importance of assessing the ability of the two knowledge routes - source and recipient - to promote effective results.

In presenting a theoretical framework that outlines the moderating effect of disseminative capacity and absorptive capacity on knowledge internalization, as a result of an effective knowledge transfer process, this paper proposes an extension of internalization, taking into consideration the dimensions of the appropriation of knowledge and the time taken for knowledge internalization. This perspective in turn suggests that knowledge internalization is a multidimensional variable, which should be evaluated by other aspects that may help in understanding other factors (appropriation and time) that must be taken into account in the analysis of the knowledge transfer process.

In this sense, this study has implications and contributions for reflection and understanding of the heterogeneity of the knowledge internalization variable. The model provides propositions empirically proven, which can help organizations achieve faster and more lasting results. As proposed in the framework, organizations with high disseminative capacity and absorptive capacity can contribute to a faster knowledge transfer process, reducing effort and time (Szulanski, 1996; Szulanski et al., 2016). Moreover, high disseminative and absorptive capacities will also assist in the appropriation of internalized knowledge, bringing satisfactory, effective and lasting results (Kostova & Roth, 2002).

That said, it is believed that the proposal of a theoretical framework represents a more complete analysis in relation to the variables that can inhibit or encourage knowledge internalization, extending the understanding of the extent of internalization.

5. Conclusions

The aim of this paper was to propose a theoretical framework using knowledge internalization as dependent variable to analyze the effectiveness of the knowledge transfer process, taking into account the variables that can jeopardize the outcome of the process. In sum, after extensive review of the literature on knowledge transfer, this study was concerned to emphasize the variables (disseminative capacity and absorptive capacity) that can interfere with the effectiveness of internalization process, which positive results may improve the competitive performance of organizations. The paper also includes an assessment of the moderating effect of these variables considering the appropriation of external knowledge by the receiver, and the process of timing of maturation as an extension of knowledge internalization in the organizational routine.

Considering the literature reviewed in this paper and based on proposals presented in the theoretical framework, we believe that this study may contribute in relation to: (i) serving as a theoretical basis for researchers' knowledge internalization themes, taking into account the literature systematization of disseminative capacity and absorptive capacity, often worked on separately by researchers in this area; (ii) progressing the area of research by proposing an extension of knowledge internalization, analyzing the dimensions of the appropriation of knowledge and the time factor as the result of the internalization composition, and (iii) presenting a broad and extensive theoretical model that could be adopted for empirical research.

A limitation of the theoretical model developed and presented in this study that future research can address, is the fact that we didn´t consider another moderating variables of the knowledge transfer process, such as motivation to learn (Hamel, 1991) or social integration (Van Wijk et al., 2008). Therefore, we suggest that future research should include moderating variables not considered in that model, but which can influence the results of the internalization process.

Moreover, we believe that the theoretical model developed and presented is useful for future empirical research in order to verify the actual results of the knowledge transfer process. In this sense, studies on this topic can offer great contributions to companies that gradually acquire knowledge as major competitive weapons to survive and thrive in a business environment which is increasingly dynamic and unstable.

REFERENCES

Ancori, B., Bureth, A., & Cohendet, P. (2000). The economics of knowledge: the debate about codification and tacit knowledge. Industrial and Corporate Change, 9(2), 255-287. [ Links ]

Araújo, M. S. B., Duarte, R. G., & Castro, J. M. (2015). Transferência de práticas produtivas entre subsidiárias de Empresas Multinacionais (EMNs) e fornecedores locais: o caso da Sigma. Gest. Prod. [online], 22(3), 649-661. [ Links ]

Argote, L., & Ingram, P. (2000). Knowledge transfer: A basis for competitive advantage of firms. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 82, 150-169. [ Links ]

Becerra, M., Lunnan, R., & Huemer, L. (2008). Trustworthiness, risk, and the transfer of tacit and explicit knowledge between alliance partners. Journal of Management Studies, 45(4), 691-713. [ Links ]

Cabrera, E. F., & Cabrera, A. (2005). Fostering knowledge sharing through people management practices. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16(5), 720-735. [ Links ]

Chappin, M. M., Cambre, B., Vermeulen, P. A., & Lozano, R. (2015). Internalizing sustainable practices: a configurational approach on sustainable forest management of the Dutch wood trade and timber industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 107, 760-774. [ Links ]

Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: a new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128-152. http:// dx.doi.org/10.2307/2393553 [ Links ]

Cummings, J. (2003). Knowledge sharing: A review of the literature. Operations Evaluation Department Working Paper, World Bank. [ Links ]

Easterby-Smith, M., Lyles, M. A., & Tsang, E. W. K. (2008). Inter-organizational knowledge transfer: current themes and future prospects. Journal of Management Studies, 45(4), 677-690. [ Links ] doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2008.00773.

Hamel, G. (1991). Competition for competence and inter-partner learning within international strategic alliances. Strategic Management Journal, Summer Special Issue, 12, 83-103.

Jansen, J. J. P., Van Den Bosch, F. A. J., & Volberda, H. W. (2005). Managing potential and realized absorptive capacity: How do organizational antecedents matter? Academy of Management Journal, 48, 999-1015. [ Links ]

Knoppen, D., Sáenz, M. J., & Johnston, D. A. (2011). Innovations in a relational context: Mechanisms to connect learning processes of absorptive capacity. Management Learning, 42(4), 419-438. [ Links ]

Kostova, T. (1999). Transnational transfer of strategic organizational practices: a contextual perspective. Acad. Manage. Rev., 24(2), 308-324. [ Links ]

Kostova, T., & Roth K. (2002). Adoption of an organizational practice by subsidiaries of multinational corporations: institutional and relational effects. Acad. Manage Rev. J., 45(1), 215-233. [ Links ]

Lane, P. J., Koka, B. R., & Pathak, S. (2006). The reification of absorptive capacity: A critical review and rejuvenation of the construct. Academy of Management Review, 31(4), 833-863. [ Links ]

Lane, P. J., & Lubatkin, M. (1998). Relative absorptive capacity and interorganizational learning. Strategic Management Journal, 19(5), 461-477. [ Links ]

Lane, P. J., Salk, J. E. & Lyles, M. A. (2001). Absorptive capacity, learning, and performance in international joint ventures. Strategic Management Journal, 22, 1139-61. [ Links ]

Minbaeva D., Pedersen T., Bjöjkman I., Fey C., & Park H. J. (2003). MNC knowledge transfer, subsidiary absorptive capacity and HRM. J. Int. Bus. Stud., 34(6), 586-599. [ Links ]

Minbaeva, D., & Michailova, S. (2004). Knowledge transfer and expatriation practices in MNCs: The role of disseminative capacity. Employee Relations, 26(6), 663-679. [ Links ]

Mu, J., Tang, F., & MacLachlan, D. (2010). Absorptive and disseminative capacity: knowledge transfer in intra-organization networks. IEEE Engineering Management Review, 3(40), 44-57. [ Links ]

Noblet, J. P., & Simon, E. (2012). The role of disseminative capacity in knowledge sharing: Which model can be applied to SMEs. Probl. Perspect. Manag, 10, 57-66. [ Links ]

Penna, L., & Castro, J. M. (2015). A internalização do conhecimento como medida efetiva de resultados de transferência de conhecimento interfirmas: a proposta de um framework teórico. 12th International Conference on Information Systems & Technology Management - Contecsi. 12,1-30.

Pérez-Nordtvedt, L., Kedia, B. L., Datta, D. K., & Rsheed, A. A. (2008). Effectiveness and efficiency of cross-border knowledge transfer: An empirical examination. Journal of Management Studies, 45(4), 699-729. [ Links ]

Sammara, A. and Biggiero, L. (2008). Heterogeneity and specificity of inter-firm knowledge flows in innovation networks. Journal of Management Studies, 45, 785-814.

Scott, C. L., & Sarker, S. (2010). Examining the Role of the Communication Channel Interface and Recipient Characteristics on Knowledge Internalization: A Pragmatist View. Forthcoming at IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication. [ Links ]

Szulanski, G. (1996). Exploring internal stickiness: impediments to the transfer of best practice within the firm. Strat. Manage. J. Special, 17, 27-44. [ Links ]

Szulanski, G. (2000). The process of knowledge transfer: a diachronic analysis of stickiness. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 82(1), 9-27. [ Links ]

Szulanski, G., & Cappetta, R. (2003). Stickiness: Conceptualizing, measuring, and predicting difficulties in the transfer of knowledge within organizations. The Blackwell handbook of organizational learning and knowledge management, 513-534. [ Links ]

Szulanski, G., Ringov, D., & Jensen, R. J. (2016). Overcoming stickiness: How the timing of knowledge transfer methods affects transfer difficulty. Organization Science, 27(2), 304-322. [ Links ]

Tang, F., Mu, J., & MacLachlan, D. L. (2010). Disseminative capacity, organizational structure and knowledge transfer. Expert Systems with Applications, 37, 1586-1593. [ Links ]

Tsai, M. T., & Lee, K. W. (2006). A study of knowledge internalization: from the perspective of learning cycle theory. Journal of Knowledge Management, 10(3), 57-71. [ Links ]

Van den Bosch, F. A. J., Van Wijk, R. V., & Volberda, H. W. (2003). Absorptive capacity: Antecedents, models and outcomes. In M. Easterby-Smith and M. Lyles (Eds.) The Blackwell handbook of organizational learning and knowledge management (pp. 278-302). Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Van Wijk, R., Jansen, J. J., & Lyles, M. A. (2008). Inter‐and intra‐organizational knowledge transfer: a meta‐analytic review and assessment of its antecedents and consequences. Journal of Management Studies, 45(4), 830-853. [ Links ]

Veja-Jurado, J., Gutièrrez-Gracia, A., & Fernándes-de-Lucio, I. (2008). Analyzing the determinants of firm´s absorptive capacity: beyond R&D. R&D Management, 38(4), 392-405. [ Links ]

Winter, S. (1987). Knowledge and competence as strategic assets. In Tee & Karney & D. Karneyce (eds.), The Competitive Challenge: Strategies for Industrial Innovation and Renewal (pp. 159-184). Cambridge, MA: Ballinger.

Yih-Tong Sun, P., & Scott, J. L. (2005). An investigation of barriers to knowledge transfer. Journal of Knowledge Management, 9(2), 75-90. [ Links ]

Zahra S., & George G. (2002). Absorptive capacity: a review, reconceptualization, and extension. Acad. Manage. Rev., 27(2), 185-203. [ Links ]

Acknowledgement

We appreciate the support of Fundação Ezequiel Dias (FUNED) and the financial support of Fundação de Amparo á Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG) for this research.

Received: 02.06.2016

Revisions required: 02.07.2016

Accepted: 10.10.2016