Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.13 no.3 Faro set. 2017

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Film-induced tourism: a systematic literature review

Turismo cinematográfico: revisão sistemática da literatura

*Lucília Cardoso, ** Cristina Estevão, *** Cristina Fernandes, **** Helena Alves

*Universidade Lusófona do Porto, R. de Augusto Rosa 24, 4000-098 Porto, Portugal, e CEPESE (Centro de Estudos da População, Economia e Sociedade), Grupo de Investigação de Património, Cultura e Turismo, lucyalves.lucilia@gmail.com

**Instituto Politécnico de Castelo Branco – Escola Superior de Gestão e NECE – Núcleo de Estudos em Ciências Empresariais, Portugal, cristina.estevao@ipcb.pt

***Instituto Politécnico de Castelo Branco – Escola Superior de Gestão e NECE – Núcleo de Estudos em Ciências Empresariais, Portugal, cristina.fernandes@ipcb.pt

****Universidade da Beira Interior e NECE – Núcleo de Estudos em Ciências Empresariais, Portugal, halves@ubi.pt

ABSTRACT

The “film-induced tourism” concept serves for the study of tourism visits made to a destination or attraction resulting from its featuring in cinema films, television series or promotional videos. This phenomenon falls within the field of “film-induced versus destination branding image” research, a fairly recently established field, and with this article correspondingly seeking to carry out analysis of the contents and systematisation of this area based on the contents of the Web of Science database. Thus, this article consists of the application of a systematic survey involving the summary and evaluation based upon the interpretation of the results returned. The sample contains only those articles published in English language journals and explicitly excluding conference proceedings or commentaries. We thus sought to grasp the perspectives adopted by both empirical and theoretical studies, the themes studied and the main conclusions of those studies analysed here. The results convey the diversity of both the quantitative and qualitative studies and the various future lines of research defined in accordance with the gaps detected in the results returned.

Keywords: Destination branding image, language of tourism, film tourism, promotional film, film-induced tourism.

RESUMO

O conceito de “film-induced tourism” é aplicado ao estudo das visitas turísticas a um destino ou atracão turística pelo resultado da exposição a filmes de cinema, series televisivas, ou vídeos promocionais. Este fenómeno enquadra-se no campo de investigação de “film-induced versus destination branding image”, sendo consideravelmente recente e nesse sentido o presente trabalho tem por objetivo realizar uma análise de conteúdo e sistematização dos artigos sobre esse campo, tendo como base de dados a web of science. O propósito do trabalho consistiu na aplicação de uma revisão sistemática envolvendo a síntese e a avaliação com base na interpretação. Foram mantidos na base apenas os artigos que tivessem sido publicados em periódicos no idioma inglês e não fossem proceedings ou comentários. Procurou-se perceber em que perspetiva os estudos empíricos foram analisados, quais as temáticas estudadas e as principais conclusões dos estudos analisados. Os resultados apresentam uma diversidade de estudos quantitativos e qualitativos e várias futuras linhas de investigação foram delineadas em função dos gaps detetados nos resultados encontrados.

Palavras-chave: Branding da imagem de destinos, linguagem do turismo, filme turístico, filme promocional, turismo cinematográfico.

1. Introduction

Given a global framework characterised by the multiple tensions, crises and instability in many countries, tourism increasingly gets referenced as the leverage for economic recovery in keeping with its capacity to generate employment and wealth. Tourism, as a system, includes tourists, places, territories, tourism networks, markets, practices, laws, values and the interactions between social institutions, among others. Hence, taking into account this perspective on tourism as a system and the current economic conjuncture, tourism related phenomena play an essential role in this globalising world. Going global, establishing a positive position and attracting new clients is just as important to countries and companies as it is to tourist destinations (Cerviño, 2007). From the outset, inherent to its nature as a system, we understand the tourism sector to be undergoing constant change and transformation and hence with equally ongoing competition between the respective tourism products and destinations.

Increasingly, tourism destinations get perceived subjectively in accordance with various and diverse psychological and sociological conditions alongside the cultural and motivational circumstances of the consumers themselves. The technological component and the revolution in information and communication technologies has meant each tourist becomes ever better informed and correspondingly more demanding. Not only are markets becoming increasingly heterogeneous but there is also a progressive rise in both the sophistication of tourists and the numbers seeking out authentic experiences with tourists now, instead of looking for a destination, seeking experiences and dreams made true. From the outset, these alterations in the habits and expectations of tourists mean that tourist destinations should design their own brands that then need managing in accordance with a strategic point of view (Blanco, 2015).

Destinations primarily compete based upon their perceived images in relation to those held of their competitors in the marketplace (Baloglu and Mangaloglu, 2001). Thus, destination managers necessarily have to undertake a whole series of marketing based actions to ensure their best positioning in a competitive marketplace for tourism attractions. Therefore, the branding of a tourism destination becomes necessary as the images held of destinations inherently shape the choices made by consumers. Hence, with the quantity of tourism destinations available, the importance of appropriately managing the destination branding image has never been so great and within this framework, the induction of image plays a crucial role. Within this perspective, destination branding is subject to various promotional means that serve as inductive agents or stimulators of the destination image and correspondingly structuring the working of the images induced (Cardoso and Marques, 2016)). There is an enormous variety in the inductive means for tourism destination images (pamphlets, posters, outdoors, etc.), nevertheless, the ongoing technological revolution, powered by swift access to information, provided by the Internet in conjunction with virtual social network related phenomena, is rewriting the dynamics underlying tourism (sharing of images, uploading films, etc.). Here, we focus our attention on tourism promotional films. Hao & Ryan (2013) state that interpreting film language is key to fostering the image of a destination and hence represents an excellence tool for transforming a particular place.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no existing study of the generic themes approached here and hence this article represents a contribution of relevance to this field of study. Hence, we correspondingly seek to contribute to deepening and systematising the impact of tourism promotional films through a survey of the research lines standing most to the fore as well as those still requiring further research. Furthermore, the aims include the systematisation of the conclusions of the various studies on this theme that have also contributed to the knowledge the tourism destinations themselves need to advance with strengthening and deepening their deployment of strategic branding.

2. Destination branding image and film-induced tourism

The brand of a tourism destination encapsulates its abilities to attract visitors and consists of the ways in which persons recall the images of this destination (Man and Aruas-Bolzmann, 2007). Destination branding contains three different components: destination identity, personality and image (Hosany et al., 2007). The branding identity conveys the contents that destination managers want tourists to perceive around the destination branding (which clearly cannot always correspond to reality), meanwhile, the personality of the brand is the factor of distinction in the marketplace and the brand benefits (emotional, status, image) convey the needs and desires of the consumer. Image is the crucial factor within this branding process as this consists of the sum of the beliefs, ideas and impressions that tourists hold in their minds about the tourist destination. The studies by Gallarza et al. (2002) and Prenbensen (2007) adopt the abbreviation TDI (Tourism Destination Image), and generally deemed an attitudinal construct consisting of an individual mental representation of knowledge (beliefs), feelings and the overall impression about the tourism destination (Baloglu & McCleary, 1999).

TDI contains three hierarchically distinct but interrelated components: cognitive, affective and global. The cognitive component encapsulates the sum of the beliefs and attitudes about the tourism destination based on the images internally accepted about its attributes (Baloglu & McCleary, 1999) that is, images of the attractions that the destination contains and susceptible to attracting tourists (Gartner, 1994). The affective component, in turn, is perceived as the set of motives that lead each tourist to select a specific tourist destination or, furthermore, that which the tourist seeks to obtain from the destination taking into account the affective evaluation of this place. And still furthermore, these affective evaluations correspond to the affective and emotional responses when faced by the destination as an objective reality. As regards the global image of the tourism destination, the literature is unanimous in considering that such derives from the perceptual/cognitive and affective evaluations of this place with these two evaluative dimensions coming together to form the overall image of the tourism destination (Cardoso, 2010).

Within the TDI formation process, there are two levels of image: the organic images and the induced images. The organic images stem from exposure to the media (newspapers, magazines, television programs) and other sources of information (the cultural component, knowledge in general, information from friends, among others), where there is no direct connection with the commercial component of the tourism destination. That induced, as the name suggests, emerges from the actions of inducing/instigating and those under the influence of the information issued by tourism organisations (Gartner, 1994; Cardoso & Marques, 2015). Therefore, destination managers may use the diverse tools established with the goal of inducing images and including that of the tourism promotional film.

Film associated promotion proves an excellence tool for fostering awareness in the minds of tourists as they present the characteristics of the tourism product and build up the destination image. Their specific advantages as regards the alternative means of communication is that they appeal to the emotions and the visual images prior to the tourists arriving at the destination (Mathisen and Prebensen, 2013). The potential effect of films themselves generates a new and special form of tourism whether called “film tourism” or “film-induced tourism” or “movie-induced tourism” (Connell, 2012; Hao and Ryan, 2013). The term "film-induced tourism" was first introduced by Beeton in 2005 in his book bearing the same title in which the author proposed this concept in place of “movie-induced tourism” in order to expand the category to include television films and mini-series (Pennacchia, 2015). The concept, associated with new forms of tourism, spans the visits made to the sites and sets of such films, whether full length feature films or television programs and series and correspondingly including theme parks and cultural heritage sites, visits to famous film studies, tourism destination promotional films with celebrities, thus, anything and everything involving the audio-visual domain and tourism visits. The concept also appears in French entitled “cinétourisme” and also inherently associated with cinema. In this case, the locations are interconnected with late celebrities such as Marilyn Monroe, James Dean, George Reeves, Farrah Fawcett, among others (Lee & Scott & Kim, 2008). More specifically, film-induced tourism takes place whenever tourists decide to visit a place after having been attracted by projected audiovisual images.

3. Method

3.1 Planning the review

With the objective of securing replicability for future researchers, we followed a systematic review process. Generally, this conveys an overall sense of confidence and trust in the scientific research existing on a field or topic (Petticrew and Roberts, 2006). Its goal involves identifying, evaluating and summarising all of the relevant studies made in a replicable and transparent process (Tranfield et al., 2003). As the “Film-induced Tourism” research field proves simultaneously considerably recent and diverse, our intention is to apply a variation of the systematic review that involves the summary and evaluation based upon the interpretation of the results returned by the following keywords: "Cinema, Creative Industries and Tourism”, "Film-induced Tourism and Tourism Film”, "Film Advertising Tourism and Language of Tourism" and "Promotion Film".

3.2 Conducting the review and analysis

In our survey, we removed any books, book chapters, reports, conference proceedings due to variability in the peer review processes and availability restrictions. In contrast, journal articles were deemed valid for our research purposes (Podsakoff et al., 2005). Instead of restricting our research to those journals with the greatest impact in their fields, we included every article from journals indexed in the Web of Science, with this the focus of our research and hence all those articles containing “Film-induced Tourism”. We placed no time boundaries on the period of article publication and the initial survey returned a total of 104 articles. Subsequently, we carried out analysis to ascertain whether the respective articles were appropriate to the purposes of this research. We maintained in our database only those articles published in English language journals and were neither proceedings nor commentaries. Following this analysis, 65 articles were excluded and 39 retained.

The following stage in the preparation of this study consisted of the individualised analysis of these articles in an independent fashion by two researchers and to this end applying a pre-defined evaluation grid that was then subject to comparison and refinement. We then applied content analysis with its systematisation carried out through recourse to NVivo (version 11.0) software, which resulted in summarised information covering the research targets in terms of the type of study, the type of analysis, conclusions, range and similarities.

4. Results

The first analytical phase consisted of attempting to systematise the concept of “Film-induced Tourism” based upon the definitions contained in the articles. We therefore verified how this “film-induced tourism” concept was for the first time introduced by Beeton in 2005 (Hudson & Ritchie, 2006) and also interconnects with others such as: film tourism, movietourism, movie-induced tourism, cinetourism and film-reinduced tourism. We may thus state that the concept has attained consolidation in the academic community given the quantity of authors deploying the term and the meaning of this new tourism typology.

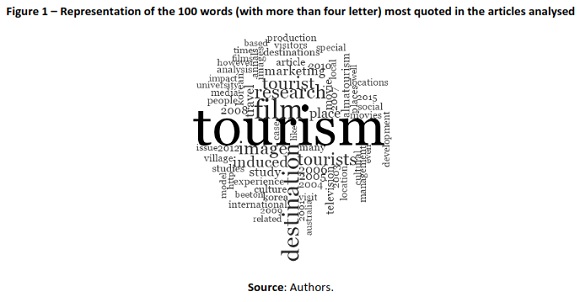

Proceeding with our exploratory analysis of the contents of the various studies under analysis, figure 1 displays the results of the representation of the 100 words with more than four letters mentioned in the articles.

As figure 1 displays, the words that most stand out are Film, Tourism, Destination, in keeping with the target of the study, but these emerge interrelated with other secondary level words that highlight the words tourist, research, image, induced, movies, marketing and destinations and therefore pre-empting to a certain extent the content of these articles that we shall return to below. Analysis of the dates of the articles, we find that their dates range between 2008 and 2015 with this final year proving that with the most studies published, in turn, reflecting the growing importance of this area of study.

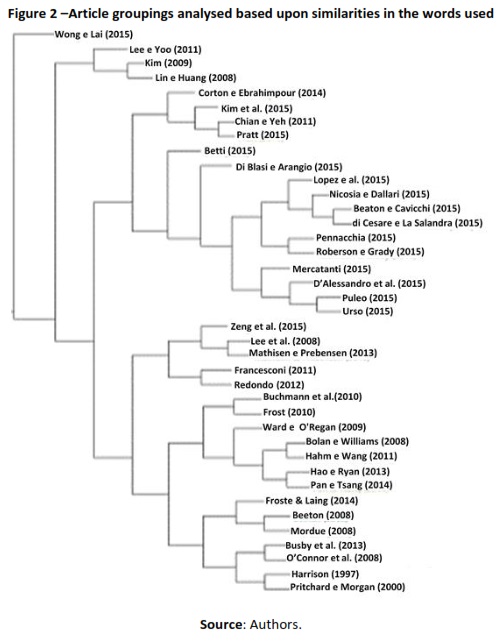

Figure 2 sets out the results of the cluster analysis that enables the grouping of articles in accordance with the similarities among their words based upon Pearson's correlation coefficient. As seen, this cluster analysis identified various groups of articles and displaying greater similarities when reading the figure from the right to the left. The analysis enabled the verification of two major groups of mutually similar articles. One group features articles by Zeng et al. (2015), Lee et al. (2008), Mathisen and Prebensen (2013), Francesconi (2011), Redondo (2012), Buchmann et al. (2010), Frost (2010), Ward e O'Regan (2009), Bolan and Williams (2008), Hahm and Wang (2011), Hao and Ryan (2013), Pan and Tsang (2014), Frost and Laing (2014), Beeton (2008), Mordue (2008), Busby et al. (2013), O'Connoret et al. (2008), Harrison (1997) and Pritchard and Morgan (2000) that above all approach the image and the marketing of tourism destinations and how films may boost the potential of both domains. A second group of articles constitutes a more homogenous subgroup distinguished by articles from authors such as Lopez et al. (2015), Nicosia and Dallari (2015), Beaton and Cavicchi (2015), di Cesare and La Salandra (2015), Pennacchia (2015), Roberson and Grady (2015), Roberson and Grady (2015), Mercatanti (2015), D'Alessandro et al. (2015), Puleo (2015) and Urso (2015), that focus their studies on the ways that film induces tourism. This group of articles also contains other articles that appear in the upper left corner of the figure as is the case, for example, of Wong and Lai (2015), and that differ in content from the remainder.

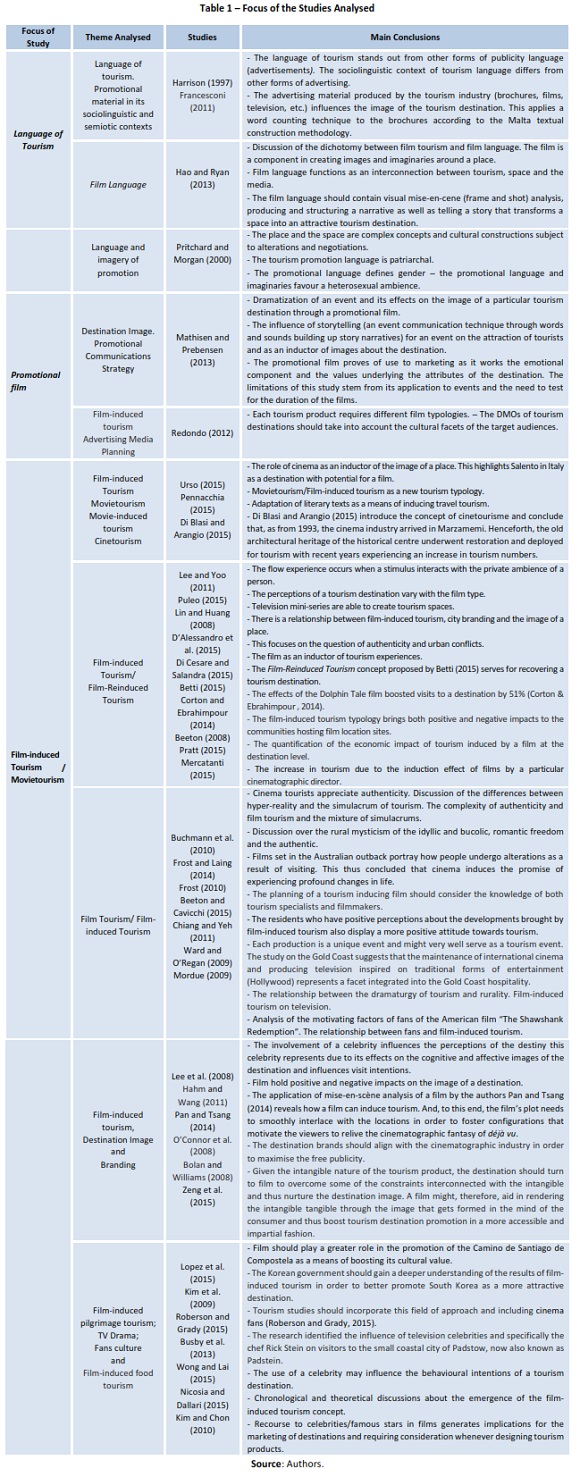

This project also sought to grasp the focus of study, the theme studied, who conducted the studies and the main conclusions of the empirical studies examined (Table 1). Examples of the focus of study are: language of tourism, promotional film and film-induced tourism/movietourism.

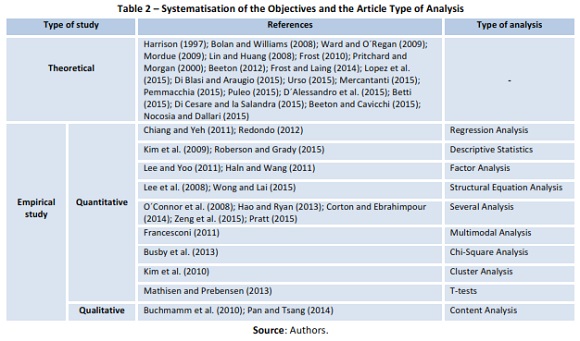

Finally, we carried out analysis of the study typologies and thus the type of analysis undertaken. In accordance with table 2, we may correspondingly state that the majority of studies are theoretical (20) while the remainder apply qualitative (2) and quantitative (17) empirical studies. The qualitative studies only feature content analysis whilst their quantitative counterparts adopted a broad variety of statistical techniques and quantitative econometric methods.

5. Conclusions

Our findings clearly point to the theme approached by this research being only very recent and at a very incipient level of development. Furthermore, within this framework, we believe this study may contribute towards the creation of value around this theme as well as defining promising future paths for research. Nevertheless, in the meanwhile, we require more robust statistical techniques in order to boost the reliability of the results.

We may also verify how the articles analysed reflect how perceptions of tourism destinations vary in accordance with the type of film and that there is a relationship between film-induced tourism, city branding and the image of a place. Furthermore, we ascertain how a film may serve as an inducer of tourism experiences, which then contributes towards the recovering of a tourism destination through boosting visitor numbers and generating a positive economic impact on the respective destination.

However, we also verify that there are authors who defend how the “film-induced tourism” typology, despite its positive impacts, may also result in negative impacts for the communities hosting the film site locations.

We therefore conclude that film constitutes a factor in the creation of the images and imaginaries of a place and that film language functions as an interconnection between tourism, the space and the media and that this should also tell a story able to transform the space into an attractive tourism destination. In addition, we may state that promotional films are fundamental to marketing as they work the emotional component and the values of the destination's attributes. Still furthermore, recourse to celebrities /famous persons in films hold implications for the marketing of destinations and therefore requires consideration in the design of any tourism product. However, each tourism product will nevertheless need different film typologies to best serve its respective promotion.

We would also highlight the fact that those residents holding positive perceptions about the developments brought by film-induced tourism also display more positive attitudes towards tourism.

This study also recognises movietourism/Film-induced tourism as a new typology of tourism.

As the main limitation of this study, we would point to how this only considers the Web of Science database and also only includes journal articles.

In future lines of research, we perceive benefits in expanding this systematic scientific article review process to study the language of tourism promotional films as regards the cinematographic techniques applied to tourism destinations and products, specifically in the analysis of the frames deployed in promotional films and correspondingly ascertaining which verbal and visual languages and shot typologies are most commonly applied in tourism communication filmed content. Research of this type may enable the construction of a tool for evaluating the quality of tourism promotional/advertising films.

REFERENCES

Beeton, S. (2008). Location, location, location: film corporations' social responsibilities. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 24(2-3), 107–114. [ Links ]

Beeton, S., & Cavicchi, A. (2015). Not quite under the Tuscan sun ... the potential of film tourism in Marche Region. Almatourism - Journal of Tourism Culture and Territorial Development, 6(4, SI), 146–160. [ Links ]

Betti, S. (2015). Film-reinduced tourism. The Hatfield-McCoy Feud case. Almatourism - Journal of Tourism Culture and Territorial Development, 6(4, SI), 117–145. [ Links ]

Blanco, J. (2015). Libro blanco de los destinos turísticos inteligentes. Madrid: LID Editorial Empresarial. [ Links ]

Bolan, P. & Williams, L. (2008). The role of image in service promotion: focusing on the influence of film on consumer choice within tourism. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 32(4), 382–390. [ Links ]

Buchmann, A., Moore, K. & Fisher, D. (2010). Experiencing film tourism authenticity & fellowship. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(1), 229–248. [ Links ]

Busby, G., Huang, R. & Jarman, R. (2013). The Stein effect: an alternative film-induced tourism perspective. International Journal of Tourism Research, 15(6), 570–582. [ Links ]

Cardoso, L. & Marques, M. (2016). Análise exploratória à “language of tourism” dos filmes do Festival ART&TUR 2014. In: Dias, F., Marques, I., Pereira, A., & Cardoso, L. (Ed.) Cinema, destination image & place branding. APTUR - Associação Portuguesa de Turismologia, 103-126. [ Links ]

Connell, J. (2012). Film tourism – evolution, progress and prospects. Tourism Management, 33(5), 1007–1029. [ Links ]

Chiang, Y. & Yeh, S. (2011). The examination of factors influencing residents' perceptions and attitudes toward film-induced tourism. African Journal of Business Management, 5(13), 5371–5377. [ Links ]

Corton, M. L., & Ebrahimpour, M. (2014). Research note: forecasting film-induced tourism - the Dolphin Tale case. Tourism Economics, 20(6), 1349–1356. [ Links ]

D'Alessandro, L., Sommella, R., & Viganoni, L. (2015). Film-induced tourism, city-branding and place-based image: the cityscape of Naples between authenticity and conflicts. Almatourism - Journal of Tourism Culture and Territorial Development, 6(4, SI), 180–194. [ Links ]

Di Blasi, E., & Arangio, A. (2015). Marzamemi, an interesting case study of film-induced tourism. Almatourism - Journal of Tourism Culture and Territorial Development, 6(4, SI), 213–228. [ Links ]

Di Cesare, F. & La Salandra, A. (2015). Film-induced, steps for a real exploitation in Europe. Almatourism - Journal of Tourism Culture and Territorial Development, 6(4, SI), 1–17. [ Links ]

Francesconi, S. (2011). Images and writing in tourist brochures. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 9(4), 341–356. [ Links ]

Frost, W. (2010). Life changing experiences film and tourists in the Australian outback. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(3), 707–726. [ Links ]

Frost, W. & Laing, J. (2014). Fictional media and imagining escape to rural villages. Tourism Geographies, 16(2, SI), 207–220. [ Links ]

Hahm, J. (Jeannie) & Wang, Y. (2011). Film-induced tourism as a vehicle for destination marketing: is it worth the efforts? Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 28(2), 165–179.

Hao, X. & Ryan, C. (2013). Interpretation, film language and tourist destinations: a case study of Hibiscus Town, China. Annals of Tourism Research, 42, 334–358. [ Links ]

Harrison, D. (1997). Barbados or Luton ? Which way to paradise? Tourism Management, 18(6), 393–398. [ Links ]

Kim, H. J., Chen, M.-H. & Su, H.-J. (2009). Research note: the impact of Korean TV dramas on Taiwanese tourism demand for Korea. Tourism Economics, 15(4), 867–873. [ Links ]

Kim, S., Lee, H. & Chon, K. (2010). Segmentation of different types of Hallyu tourists using a multinomial model and its marketing implications. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 34(3), 341–363. [ Links ]

Lee, S., Scott, D., & Kim, H. (2008). Celebrity fan involvement and destination perceptions. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(3), 809–832. [ Links ]

Lee, T. & Yoo, J. (2011). A study on flow experience structures: enhancement or death, prospects for the Korean wave. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 28(4), 423–431. [ Links ]

Lin, Y. & Huang, J. (2008). Analyzing the use of tv miniseries for Korea tourism marketing. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 24(2-3), 223–227. [ Links ]

Lopez, L., Mosquera, D., & Lois Gonzalez, R. (2015). Film-induced tourism in the Way of Saint James. Almatourism - Journal of Tourism Culture and Territorial Development, 6(4, SI), 18–34. [ Links ]

Mathisen, L., & Prebensen, N. K. (2013). Dramatizing an event through a promotional film: testing image effects. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30(7), 672–689. [ Links ]

Mercatanti, L. (2015). The seal on the seventh art: Bergman and the Faro Island. Almatourism - Journal of Tourism Culture and Territorial Development, 6(4, SI), 93–101. [ Links ]

Mordue, T. (2009). Television, tourism, and rural life. Journal of Travel Research, 47(3), 332–345. [ Links ]

Nicosia, E. & Dallari, F. (2015). Special issue film-induced tourism. Almatourism - Journal of Tourism Culture and Territorial Development, 6(4, SI), I–III. [ Links ]

O'Connor, N., Flanagan, S. & Gilbert, D. (2008). The integration of film-induced tourism and destination branding in Yorkshire, Uk. International Journal of Tourism Research, 10(5), 423–437. [ Links ]

Pan, S., & Tsang, N. (2014). Inducible or not-a telltale from two movies. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 31(3), 397–416. [ Links ]

Pennacchia, M. (2015). Adaptation-induced tourism for consumers of literature on screen: the experience of Jane Austen fans. Almatourism - Journal of Tourism Culture and Territorial Development, 6(4, SI), 261–268. [ Links ]

Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: a practical guide. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Pratt, S. (2015). The Borat effect: film-induced tourism gone wrong. Tourism Economics, 21(5), 977–993. [ Links ]

Pritchard, A., & Morgan, N. J. (2000). Privileging the male gaze - gendered tourism landscapes. Annals of Tourism Research, 27(4), 884–905. [ Links ]

Puleo, T. J. (2015). American perceptions of Sicily as a tourist destination as experienced through film. Almatourism - Journal of Tourism Culture and Territorial Development, 6(4, SI), 195–212. [ Links ]

Redondo, I. (2012). Assessing the appropriateness of movies as vehicles for promoting tourist destinations. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 29(7), 714–729. [ Links ]

Roberson, R., & Grady, M. (2015). The “Shawshank Trail”: a cross disciplinary study in film-induced tourism and fan culture. Almatourism - Journal of Tourism Culture and Territorial Development, 6(4, SI), 47–66. [ Links ]

Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., & Smart, P. (2003). Towards a methodology for developing evidence informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management, 14 (3), 207–222. [ Links ]

Urso, G. (2015). Salento atmosphere and the role of movies. Almatourism - Journal of Tourism Culture and Territorial Development, 6(4, SI), 229–240. [ Links ]

Ward, S., & O'Regan, T. (2009). The film producer as the long-stay business tourist: rethinking film and tourism from a Gold Coast perspective. Tourism Geographies, 11(2), 214–232. [ Links ]

Wong, J.-Y., & Lai, T.-C. (2015). Celebrity attachment and behavioral intentions: the mediating role of place attachment. International Journal of Tourism Research, 17(2), 161–170. [ Links ]

Zeng, S., Chiu, W., Lee, C. W., Kang, H.-W. & Park, C. (2015). South Korea's destination image: comparing perceptions of film and non-film Chinese tourists. Social Behavior and Personality, 43(9), 1453–1462. [ Links ]

Received: 05 March 2017

Revisions required: 05 April 2017

Accepted: 02 May 2017