Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.13 no.4 Faro dez. 2017

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Tourism destination brand dimensions: an exploratory approach

Dimensões da marca de destinos turísticos: uma abordagem exploratória

José Manuel Cristóvão Veríssimo*, Maria Teresa Borges Tiago**, Flávio Gomes Tiago***, João Sérgio Jardim****

*ISEG - Lisbon School of Economics and Management, Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal, jose.verissimo@iseg.ulisboa.pt

**Business and Economics Department, University of the Azores, Ponta Delgada, Portugal, maria.tp.tiago@uac.pt

***Business and Economics Department, University of the Azores, Ponta Delgada, Portugal, flavio.gb.tiago@uac.pt

****Publicis London, London, United Kingdom, sergiojardim@portugalmail.pt

ABSTRACT

Recently, researchers have suggested using destination branding as a powerful marketing tool. Despite its apparent value, there appears to be little applied research on this subject that goes beyond the conventional destination brand image, especially regarding research that combines different brand equity dimensions. This study is designed to address this gap, using the islands of Madeira as a unit of research. For this purpose, a survey was undertaken of 321 tourists, in seven hotels at this destination. Respondents were requested to rate the factors for awareness, image, perceived quality, and loyalty, in a method consistent with the brand equity model, using descriptive analyses and a confirmatory factor analysis. The results show that these four dimensions are relevant for the composition of destination brand equity. Even though image shows the greatest impact, the outcome establishes the need to look beyond brand image.

Keywords: Brand equity, awareness, image, perceived quality, loyalty, branding destinations.

RESUMO

Estudos recentes defendem a importância da gestão da marca de destinos enquanto ferramenta de marketing. Porém, apesar do seu valor potencial, poucos trabalhos aprofundam a gestão da marca para além do conceito de imagem. Este trabalho contribui para colmatar esta lacuna, utilizando a ilha da Madeira como unidade de análise e contando com a participação de 321 turistas, alojados em sete hotéis. Solicitou-se aos inquiridos a avaliação do destino nas dimensões do modelo de valor de marca, nomeadamente, imagem, notoriedade, qualidade percecionada e fidelização. Os resultados obtidos através das análises descritiva e fatorial confirmatória atestam que o modelo de valor da marca é composto por estas quatro dimensões. Embora a imagem seja uma dimensão importante do modelo, os resultados mostram que a marca de destino depende, igualmente, da notoriedade, da qualidade percecionada e da fidelização.

Palavras-chave: Valor de marca, notoriedade, imagem, valor percecionado, fidelização, gestão de marca do destino.

1. Introduction

Regions compete globally among each other to attract investors and tourists and they also tend to sell themselves in very similar ways. Thus, leveraging a destination on image alone may not be enough to gain competitive advantage. Places, regions and countries all have distinct characteristics (Caldwell & Freire, 2004), and also have an identity, awareness, quality and loyalty. These characteristics are unique and create a destination's brand.

Brand destination management has become imperative in a highly competitive sector (Pike & Page, 2014). Tourist destinations, with their tangible and intangible attributes, integrate different players, and combine distinctive resources. A vast empirical research has focused on destination image (e.g.; Prebensen, 2007). Meanwhile, research into the branding of tourist destinations is growing, adding to a limited number of studies that explore other factors, rather than image (e.g.; Konecnik, 2006; Boo, Busser Baloglu, 2009; Pike, Bianchi, Kerr & Patti, 2010).

Despite the numerous studies conducted in this domain, only a few in the non-European context analyse destination branding on small islands. Considering that tourism on small islands encompasses a significant shift in tourism paradigms, from both demand and supply perspectives, it seems relevant to focus on destination branding. Madeira is considered a “mature” destination, whose main source of income relies heavily on tourism (Oliveira & Pereira, 2008). A limited number of studies (e.g. Machado, 2010) have investigated Madeira's value as a destination, but none have evaluated the islands from a customer-based brand equity perspective.

This research assesses the dimensions of the brand equity concept in a mature destination, exploring beyond destination image, and thus adds to the recent debate on destination DNA.

2. Theoretical background

A brand is a “distinguishing name and/or symbol intended to identify the goods or services of either one seller or a group of sellers, and to differentiate those goods from those of competitors” (Aaker, 1991, p.7). Keller, Apéria and Georgson (2008) add that a brand resides in the minds of consumers. Ultimately, a brand simplifies the decision process, promises a certain level of quality, reduces risk, and is a source of trust (Aaker, 1991). Destination branding can be defined as a way to create and communicate a unique identity which is meaningful to visitors and investors, and differentiate from those adopted by competitors (Qu, Kim & Im, 2011). Blain, Levy and Ritchie (2005) posit that destination branding is the set of marketing activities that support the creation of a name, symbol, logo, word mark, or other image that readily identifies and differentiates a destination.

Destination branding has become a popular and powerful marketing tool. The abundant body of literature found under the designation of “geo-brand”, “destination marketing”, “place marketing” and “destination branding' confirmed the growing importance of the area for both scholars and practitioners alike, but has unveiled a certain amount of confusion regarding the concept of “brand” in the tourist destination context. Recently, researchers have started looking at destination DNA and unique characteristics.

Over the past two decades, several studies have been conducted to attempt to understand destination branding. Although applied widely to products and services, only a handful of studies have examined tourism destination from a branding perspective. Apostolopoulou and Papadimitriou (2015) argue that the branding of a certain region or place as a tourist destination is a long and continual process, depending on many factors and established brand management practices.

An increasing number of studies apply branding principles to tourism destinations (e.g. Konecnik & Go, 2008; Boo et al., 2009), expanding the prevailing stream of research that has been traditionally focussed on image. Tourism destinations require adaptation of branding principles that are applied to goods and services, as they are more complex and rich on attributes (Pike et al., 2010). Besides identification, destination branding allows a place to differentiate itself from its competitors, based on its special meaning and attachment, thus creating brand equity.

Brand equity

The notion of brand equity and how to measure it have been the subject of interest by many researchers (Keller 1993; Washburn & Plank, 2002), either from a financial, or a strategic perspective. The latter has received most attention, with Aaker and Keller having the most citations in the literature. Aaker (1996:7) defines brand equity as “a set of assets (and liabilities) linked to a brand's name and symbol that adds to (or subtracts from) the value provided by a product or service to a firm and/or that firm's customers”. Aaker defends that brand equity stems from five dimensions: awareness; associations; perceived quality; loyalty, and; proprietary brand assets. Keller (1993:2) coined the customer-based brand equity concept, defining it as “the differential effect of brand knowledge on consumer response to the marketing of a brand”. This occurs when the consumer holds unique brand associations. Thus, it is relevant to consider both the cognitive and affective components of a place to build a destination's DNA. Thus DNA should reflect brands' values and unique propositions in consumers' eyes (Morgan, Pritchard & Piggott, 2003).

The existing research points to an overlap between Aaker's and Keller's brand equity dimensions (Atilgan & Aksoy, 2005). However, there is still a lack of research regarding those factors that enhance brand equity. Konecnik and Gartner's (2007) research was one of the first examples to apply a four-dimensional model of brand equity to a destination. The replicability of this model is still limited (Boo et al., 2009; Kladou & Kehagias, 2014). The brand equity model examines the contribution of awareness, image, perceived quality, and loyalty on destination brand equity.

Brand awareness

Destination marketing activities seek to raise awareness and to positively impact image (Milman & Pizam, 1995; Lee, Lockshin & Greenacre, 2015; Lai & Li, 2015). Brand awareness relates to the strength of brand presence in the consumer's mind (Aaker 1991; Keller, 1993; Kapferer & Valette-Florence, 2016), and it depends on the level of involvement with the brand, ranging from simple brand recognition, to top-of-mind awareness over alternative brands (Aaker 1996). Higher levels of awareness do not necessary lead to trial or purchase (Konecnik & Gartner, 2007), as this may result from product curiosity. However, tourists who are unaware of a given destination will probably never consider it as an option.

Previous empirical research shows that brand awareness contributes to brand value (Oh, 2000; Kwun & Oh, 2004; Ruão, Marinho, Balonas, Melo & Lopes, 2016), and to also to performance (Kim & Kim, 2005; Sˇeric, Gil-Saura & Mikulic, 2016). Awareness was an important dimension in Konecnik's (2006) and Konecnik and Gartner's (2007) brand equity models, producing a significant effect on destination brand experience (Boo et al., 2009).

Brand image

Associations encompass all those memories of the consumer's mind that relate to a brand (Keller, 1993). Aaker (1991) argues that the link between the consumer and a brand will increase with the number of favourable associations gathered, thus influencing purchase decisions and brand loyalty. Both authors posit that brand associations contribute to brand image. Many academics consider brand image and brand associations as one being of a single dimension (Hosany, Ekinci & Uysal, 2007). Brand associations, combining image and attributes, can be the essence of destination DNA.

Destination DNA relies on all the characteristics of a place that attract visitors and investors, which is critical for generating conversation, discrimination, and differentiation. In short, it is the total promise that a destination makes to tourists. Therefore, while brand image symbolises the perception of tourists, destination DNA reflects the sum of brand image and destination promises to those visiting it. The challenge is thus to enhance the notion of destination branding and capture destination DNA. Understanding the link between brand image components and the intention of choosing a destination is crucial for the tourism sector (Almeida, Miranda & Almeida, 2012).

Brand perceived quality

This is without a doubt the most challenging dimension to assess, hence quality is a combination of many attribute-based variables. Perceived quality is consumer perception about the superiority and excellence of a brand, compared to alternative brands (Aaker, 1996). Perceived quality is an intangible asset, which represents a feeling about the brand. However, it is able to generate value for its owners in many ways, including positioning and differentiation against competitors. Saleem, Rahman and Umar (2015) reinforce the idea that quality is a psychological assessment, which depends on tourists' perceptual gap between the expected perceived qualities and performance.

Brand loyalty

Loyalty reflects the degree of connection between the consumer and the brand, and reveals attachment to the brand and the likelihood to change, or not, to another one (Aaker 1991). Aaker (1996) defends that loyalty is a core dimension of brand equity, as it is able to generate a reduction in the vulnerability to competitors' actions. As is apparent in several studies, two dimensions need to be acknowledge when evaluating brand loyalty, namely: the emotional and the rational.

3. Methodology

Questionnaires were self-administered to tourists present at the Madeira Flower Festival in 2012. Madeira is a Portuguese archipelago located in the North Atlantic Ocean, and is a peripheral region of the European Union. The archipelago includes the islands of Madeira, Porto Santo, and the Desertas. It is a popular year-round resort, renowned for its Madeira wine, nature, sun, and sea, as well as for its annual New Year celebrations. Madeira is a mature destination. Tourists first visited the island back in the 1850's. Since the beginning, Madeira has been known for attracting wealthier Europeans who want to escape cold winters, or who wish to simply enjoy the mild climate and the beautiful landscape that characterise the islands. According to Madeira's Regional Tourism Board (2010), most visitors originate from the United Kingdom (23%), mainland Portugal (23%), Germany (17%), and Scandinavia (10%). Tourists are active adults, aged 50 years or more, who are looking for a mix of nature, sun, and sea.

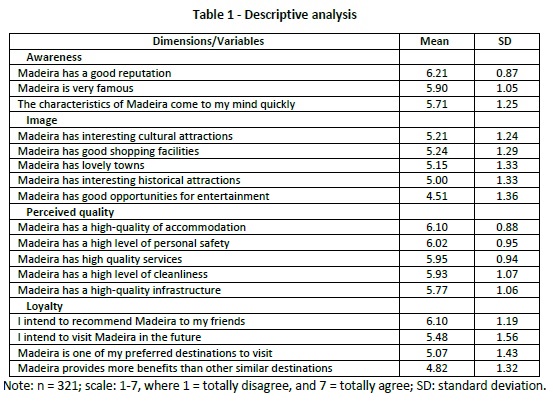

Awareness is measured by items taken from Konecnik and Gartner (2007), including “Madeira has a good reputation”, and “Madeira is very famous”, and “the characteristics of Madeira come to my mind quickly”. There is no single way to measure image. Used frequently in tourism studies, image is difficult to operationalise and to separate from other brand equity dimensions (Konecnik, 2010). Konecnik and Gartner (2007) measure image by using an attribute-based approach. On the contrary, Boo et al. (2009) measure image using a social and self-image perspective. Image is measured following Konecnik and Gartner's (2007) recommendation. Five items were used for measuring image and attributes, namely: “Madeira has interesting cultural attractions”; “Madeira has good shopping facilities”; “Madeira has lovely cities”; “Madeira has interesting historical attractions”, and; “Madeira has good opportunities for entertainment”. Perceived quality has been addressed frequently in image studies (Konecnik, 2010), and is a critical element to assess tourist experiences. Its measurement takes into account aspects such as the environment, infrastructure and amenities of the destination. In the current study, perceived quality is measured by five items taken from the work of Konecnik and Gartner (2007). The items are: “Madeira has a high quality of accommodation”; “Madeira has a high level of personal safety”; “Madeira has high quality services”; “Madeira has a high level of cleanliness”, and; “Madeira has a high quality infrastructure”. Loyalty in destination branding tends to relate it with satisfaction (Yoon & Uysal, 2005; Kim & Brown, 2012). The literature suggests that loyalty can be addressed through an attitudinal or behavioural perspective, that is to say: repetition of the visit, intention of returning, or recommendations. This study measures loyalty according to Konecnik and Gartner (2007). Loyalty is evaluated by four item, namely: “I intend to recommend Madeira to my friends”; “I intend to visit Madeira in the future”; “Madeira is one of my preferred destinations to visit”, and; “Madeira provides more benefits than other similar destinations “. All items were measured on a 7-pont Likert type scale, where 1 = “strongly disagree”, and 7 = “totally agree”. Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for the variables mentioned above.

4. Results

Demographic profile

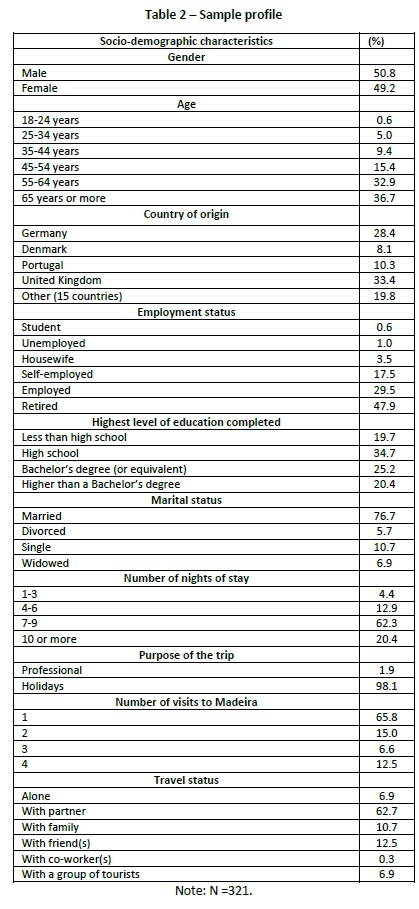

A total of 507 questionnaires were obtained, reduced to 321 after eliminating those with missing values. The final sample is considered appropriate for using structural equation modeling (Hair, Anderson, Tatham & Black, 1992). Respondents were evenly distributed between men (50.8%) and women (49.2%). The majority of the respondents were aged over 55 years (69.7%), were married (76.7%), and with at least high school completed (80.3%). Almost half of the sample is composed of retirees (47.9%). Regarding country of origin, 33.4% came from the United Kingdom, 28.4% from Germany, and the rest from 17 different nationalities, including 10.3% from mainland Portugal. Most visitors were first-timers on the island (65.8%), were on holidays (98.1%), were travelling with their partner (62.7%), and stayed in Madeira from 7 to 9 nights (62.3%). The sample characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Structural Equations Modeling

Following the literature reviewed in the previous section, we investigate the relationship among awareness, image, loyalty, and perceived quality, which are all dimensions of the brand equity model. For this purpose, we use a structural equation model with latent variables. This model includes two sub models: the measurement model and the structural equation model. The first model shows how the latent variables or factors are measured, which is suitable for the purpose of this exploratory research.

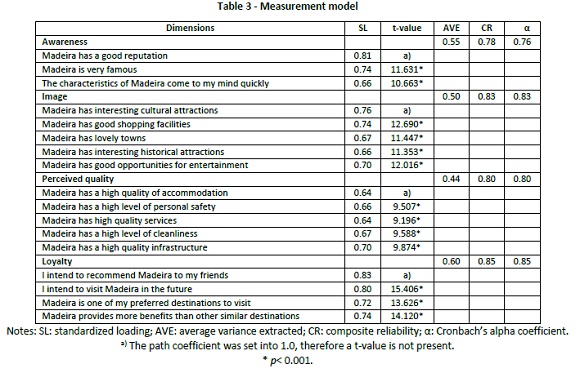

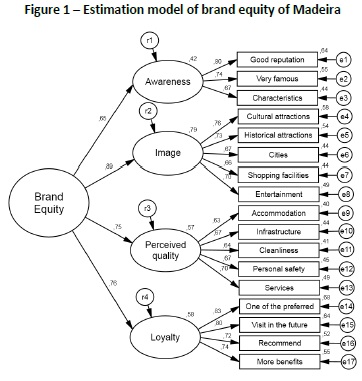

First, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) is performed for each dimension to determine their structure. The analysis is appropriate (KMO > 0.69), and the Bartlett's test of sphericity shows significant correlation (p = 0.000). The factor extraction is carried out using the principal axis factoring method, recommended when looking for a latent factor (Hair et al., 1992), and when the number of factors to be extracted is defined a priori. Variables retained follow the 0.4 minimum rule for communalities and factor loadings. Factors show appropriate reliability, as Cronbach's alpha coefficient are all above 0.76. The variance extracted ranges between 44% for perceived quality and 60% for loyalty. The convergent validity was checked through the standardised loadings of its indicators (Kline, 2010), presenting relatively high values (> 0.64). The discriminant validity was verified by comparing the average variance extracted (AVE) with the square of the correlations with the others dimensions. All dimensions are confirmed, as well as the number of indicators obtained in the EFA. The goodness fit indexes for the model are appropriate (χ2 (df = 113) = 282.23, p = 0.000; χ2/df = 2.498, GFI = 0.909, AGFI = 0.877, NFI = 0.883, CFI = 0.926, RMR = 0.071, RMSEA = 0.068, p-close = 0.001). Table 3 shows the measurement model results.

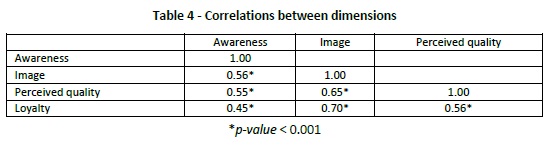

The four dimensions show a significant positive correlation (Table 4). Image correlates significantly higher with loyalty, perceived quality, and awareness.

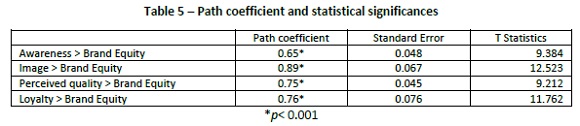

Considering the aim of scale validation for small island destination, the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) suits the purpose, as it enables the verification of the number of underlying dimensions and also indicates how the subscales should be scored (Brown, 2015). We assume that the construct of brand equity reflects not only the image, but also an awareness factor, a loyalty factor, and a factor concerned with perceived quality. Therefore, a second-order CFA is carried out to test the relationship between brand equity and the four dimensions: awareness; image; perceived quality, and; loyalty. The highest order factor that explains the covariance between the dimensions represents destination brand equity. The coefficients between the latter and each dimension indicate their importance level. The standardised coefficients between the second-order factor and the dimensions are high and statistically significant (p < 0.001). The fit indexes for the structural model are appropriate (χ2 (df = 115) = 286.23, p = 0.000; χ2/df = 2.489; GFI = 0.908; AGFI = 0.877; NFI = 0.882; CFI = 0.925; RMR = 0.071; RMSEA = 0.068, p-close = 0.002). The main fit indexes of the model are identical to those obtained in the measurement model. The path coefficients and statistical significances are presented in Table 5.

All subscales contribute to destination brand equity, but not necessarily in the same manner. Image shows the highest significant standardised coefficient (0.89), followed by loyalty (0.76), perceived quality (0.75), and awareness (0.65). The structural model is shown in Figure 1.

The results indicate that all paths are significant at p < .001 in the estimate model. By testing the relationships between the constructs of awareness, image, perceived quality, and loyalty using CFA, a comparable analytical framework can be adopted. The viability of the results of the single total score for brand equity indicates that the subscales found are suitable to measure brand equity when applied to small and mature islands destination.

5. Discussion

This research applies the concept of brand equity to a mature destination of small islands, and contributes to destination DNA management by unveiling most of the subscales within the concept. Results show that the value assigned to a destination goes beyond the image associated with that place. Instead, destination branding should be addressed in a more holistic manner, image being one of the multiple drivers, but should also include awareness, perceived quality, and loyalty (Ruão et al., 2016; Saleem et al., 2015).

The results show that awareness, image, perceived quality, and loyalty are all relevant to destination brand equity, with image emerging as the most important factor. This confirms the role of image in tourism marketing. In Konecnik and Gartner's (2007) study of Slovenia, image emerged as the core dimension for the Croatian market. Loyalty is the second most important dimension that influences destination brand equity. To some (Yoon & Uysal, 2005; Saleem et al., 2015), loyalty results from satisfaction. Perceived quality, associated with the recognition of excellence and the superiority of the brand, also has an impact on brand equity. Unsurprisingly, perceived quality is considered a crucial element when evaluating tourists' experience (Ruão et al., 2016; Saleem et al., 2015). Though important, awareness contributes to brand equity less than the other three dimensions. One possible explanation for this is the role of knowledge in the early stage of the selection process. Arguably, experience reinforces the dimensions 'maturing' during a stay.

The findings suggest that destination brand management should promote consistent and integrated strategies, taking into account that, in order to improve the brand equity of a destination, strategies should improve awareness in early stages, as well as quality and practices that create favourable image perceptions and future intentions to return. For example, destination brand managers should examine the resources that they have on offer, ascertain the requirements of the target markets, and then develop marketing strategies that create favourable associations which make the destination stand out during the selection process. Brand managers should also ensure that the customer experience matches, or exceeds expectations, whilst enhancing loyalty and promoting word of mouth recommendation.

This study has certain limitations. Firstly, the results do not factor in changes in experience over time. Secondly, the participants are all voluntary visitors, and thus self-reported measures may not be representative of the tourist population as a whole. Thirdly, image was approached by using an attribute-based perspective, which could lead to information loss. Finally, other factors influencing destination brand equity may be missing from the analysis, which is a shortcoming that can be addressed by including other factors, such as brand trust and brand personality.

REFERENCES

Aaker, D. A. (1991). Managing Brand Equity: Capitalizing on the Value of a Brand Name. New York, NY: Free Press.

Aaker, D. A. (1996). Building Strong Brands. New York, NY: Free Press.

Almeida, P., Miranda, F. J., & Almeida, A. E. (2012). Importance/value analyses applied to image components of a tourism destination. Tourism & Management Studies, 8, 65-77. [ Links ]

Apostolopoulou, A., & Papadimitriou, D. (2015). The role of destination personality in predicting tourist behaviour: implications for branding mid-sized urban destinations. Current Issues in Tourism, 18(12), 1132-1151. [ Links ]

Atilgan, E., & Aksoy, S. (2005). Determinants of the brand equity: A verification approach in the beverage industry in Turkey. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 23(3), 237-248. [ Links ]

Blain, C., Levy, S. E., & Ritchie, J. B. (2005). Destination branding: Insights and practices from destination management organizations. Journal of Travel Research, 43(4), 328-338. [ Links ]

Boo, S., Busser, J., & Baloglu, S. (2009). A model of customer-based brand equity and its application to multiple destinations. Tourism Management, 30(2), 219-231. [ Links ]

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research, 2nd edition. New York: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Caldwell, N., & Freire, J. R. (2004). The differences between branding a country, a region and a city: Applying the Brand Box Model. The Journal of Brand Management, 12(1), 50-61. [ Links ]

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R., Tatham, R., & Black, W. (1992). Multivariate data analysis with readings. 3rd edition. New York: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Hosany, S., Ekinci, Y., & Uysal, M. (2007). Destination image and destination personality. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 1(1), 62-81. [ Links ]

Kapferer, J. N., & Valette-Florence, P. (2016). Beyond rarity: the paths of luxury desire. How luxury brands grow yet remain desirable. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 25(2), 120-133. [ Links ]

Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1-22. [ Links ]

Keller, K. L., Apéria, T., & Georgson, M. (2008). Strategic Brand Management: an European perspective. Harlow: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Kim, A. K., & Brown. G. (2012). Understanding the relationships between perceived travel experiences, overall satisfaction, and destination loyalty. Anatolia: An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 23(3), 328-347. [ Links ]

Kim, H. B., & Kim, W. G. (2005). The relationship between brand equity and firms' performance in luxury hotels and chain restaurants. Tourism Management, 26(4), 549-560. [ Links ]

Kladou, S., & Kehagias, J. (2014). Assessing destination brand equity: An integrated approach. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 3(1), 2-10. [ Links ]

Kline, R. B. (2010). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3rd edition. New York: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Konecnik R. M., & Go, F. (2008). Tourism destination brand identity: The case of Slovenia. Brand Management, 15(3), 177-189. [ Links ]

Konecnik, R. M. (2006). Croatian-based brand equity for Slovenia as a tourism destination. Economic and Business Review for Central and South – Eastern Europe, 8(1), 83-108. [ Links ]

Konecnik, R. M. (2010). Clarifying the Concept of Customer-Based Brand Equity for a Tourism Destination. Annales, Series Historia et Sociologia, 2(1), 189-200. [ Links ]

Konecnik, R. M., & Gartner, W. C. (2007). Customer-based brand equity for a destination. Annals of Tourism Research, 34(2), 400-421. [ Links ]

Kwun, J. W., & Oh, H. (2004). Effects of brand, price, and risk on customers' value perceptions and behavioural intentions in the restaurant industry. Journal of Hospitality & Leisure Marketing, 11(1), 31-49. [ Links ]

Lai, K., & Li, X. (Robert). (2015). Tourism Destination Image: Conceptual Problems and Definitional Solutions. Journal of Travel Research. Doi: 10.1177/0047287515619693. [ Links ]

Lee, R., Lockshin, L., & Greenacre, L. (2015). A Memory Theory Perspective of Country Image Formation. Journal of International Marketing, 24(2), 62-79. [ Links ]

Machado, L.P. (2010). Does destination image influence the length of stay in a tourism destination? Tourism Economics, 16(2), 443-456. [ Links ]

Milman, A., & Pizam, A. (1995). The role of awareness and familiarity with a destination: The central Florida case. Journal of Travel Research, 33(3), 21-27. [ Links ]

Morgan, N. J., Pritchard, A., & Piggott, R. (2003). Destination branding and the role of the stakeholders: The case of New Zealand. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 9(3), 285-299. [ Links ]

Oh, H. (2000). The effect of brand class, brand awareness, and price on customer value and behavioural intentions. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 24(2), 136-162. [ Links ]

Oliveira, P.; Pereira, P.T. (2008). Who values what in a tourism destination? The case of Madeira Island. Tourism Economics, 14(1), 155-168. [ Links ]

Pike, S., & Page, S.J. (2014). Destination Marketing Organizations and destination marketing: A narrative analysis of the literature. Tourism Management 41, 202-227. [ Links ]

Pike, S., Bianchi, C., Kerr, G., & Patti, C. (2010). Consumer-based brand equity for Australia as a long haul tourism destination in an emerging market. International Marketing Review, 27(4), 434-449. [ Links ]

Prebensen, N. K. (2007). Exploring tourists' images of a distant destination. Tourism Management, 28(3), 747-756. [ Links ]

Qu, H., Kim, L. H., & Im, H. H. (2011). A model of destination branding: Integrating the concepts of the branding and destination image. Tourism Management, 32(3), 465-476. [ Links ]

Ruão, T., Marinho, S., Balonas, S., Melo, A. D., & Lopes, A. I. (2016). Brand Management at a Local Scale: A Case of ‘Ghost Awareness'. Corporate Reputation Review, 19(2), 179-193. [ Links ]

Seric, M., Gil-Saura, I., & Mikulic, J. (2016). Customer-based brand equity building: Empirical evidence from Croatian upscale hotels. Journal of Vacation Marketing. Doi: 10.1177/1356766716634151. [ Links ]

Saleem, S., Rahman, S. U., & Umar, R. M. (2015). Measuring Customer Based Beverage Brand Equity: Investigating the Relationship between Perceived Quality, Brand Awareness, Brand Image, and Brand Loyalty. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 7(1), 66-77. [ Links ]

Washburn, J., & Plank, R. (2002). Measuring brand equity: An evaluation of a consumer-based brand equity scale. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 1(1), 46-62. [ Links ]

Yoon, Y., & Uysal, M. (2005). An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: a structural model. Tourism Management, 26(1), 45-56. [ Links ]

Received: 19.10.2016

Revisions required: 20.02.2017

Accepted: 30.04.2017