Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.13 no.4 Faro dez. 2017

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Changes in the Guimarães visitors` profile and the city attributes perceptions in the post hosting of the 2012 European Capital of Culture

Alterações no perfil dos visitantes de Guimarães e na perceção dos atributos da cidade após o acolhimento da Capital Europeia da Cultura 2012

Paula Cristina Remoaldo*, Laurentina Vareiro**, José Cadima Ribeiro**

*Lab2pt and Department of Geography, University of Minho, Guimarães, Portugal, premoaldo@geografia.uminho.pt

**UNIAG and School of Management, Polytechnic Institute of Cávado and Ave, Barcelos, Portugal, lvareiro@ipca.pt

***NIPE and School of Economics and Management, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal, jcadima@eeg.uminho.pt

ABSTRACT

The European Capitals of Culture (ECOC) are the most ambitious European cultural partnership project implemented in Europe, if one looks at its scale. In 2012, for the first time in Portugal, a medium sized city was its host. Guimarães (in the northwest of Portugal) was the city chosen. Three years after hosting the ECOC, it is time to assess what has changed as a consequence of hosting the event in terms of visitors' profile and the perception of the city´s attributes. Primary data sources were used, gathered via conducting surveys on tourists in the ex-ante (2010/11) and post-event periods (2015) to Guimarães. Analytically, statistical methods were used putting in evidence the similarities and /or differences found regarding the visitors' profiles and perceptions towards the destination´s attributes, when looking at the two time periods being analyzed. In relation to the results achieved, it was concluded that a change in the visitors' profile to Guimarães took place (there was a more balance between men and women; a decrease in the amount of tourists aged from 0 to 25 and an increase in those aged from 46 to 65; as well as an increase in tourists with lower schooling levels), aside from a notorious evolution in what regards the perceived city attributes. One believes that the empirical results attained are a valuable source of information for tour operators and, mainly, for city planning and for the managing authorities.

Key-words: visitors' profile; destination attributes perceptions; 2012 European Capital of Culture; Guimarães.

RESUMO

As Capitais Europeias da Cultura (CEC) são o projeto colaborativo de âmbito cultural mais ambicioso concretizado na Europa, se se considerar a respetiva escala. Em 2012, pela primeira vez em Portugal, uma cidade de dimensão média acolheu uma CEC. Guimarães, situada no noroeste do país, foi a cidade escolhida. Três anos depois, entendemos que era tempo de avaliar o que mudou como consequência do acolhimento do evento em termos de perfil do visitante e perceção dos atributos da cidade. Foram usados dados primários recolhidos através de um inquérito aplicado aos turistas de Guimarães nos períodos ex-ante (2010/2011) e ex-post (2015). Na análise, recorreu-se a métodos estatísticos que permitissem pôr em evidência as similaridades e/ou diferenças nos perfis dos visitantes e nas perceções destes referentes aos atributos do destino, considerando os dois momentos de análise. Em função dos resultados alcançados, concluiu-se que ocorreu uma mudança no perfil do visitante de Guimarães (no período posterior face ao período inicial, constatou-se um maior balanceamento entre homens e mulheres, um decréscimo na quantidade de turistas entre os 0 e os 25 anos de idade, e um incremento dos entre 45 e os 65 anos, assim como dos detentores de mais baixos níveis de escolaridade), aparte uma notória evolução no que respeita à perceção dos atributos da cidade. Acredita-se que os resultados empíricos obtidos podem ser uma fonte de informação relevante para os operadores turísticos e, sobretudo, para as entidades responsáveis pelo planeamento e gestão da cidade.

Palavras-chave: perfil do visitante; perceção dos atributos do destino; Capital Europeia da Cultura de 2012; Guimarães.

1. Introduction

To the present date, the European Capital of Culture (ECOC) has been hosted three times by Portugal (1994, 2001 and 2012), although very little was written about its legacy. Keeping in mind the aims of the mega-event, it was important to know the kind of impacts the hosting of those ECOC had in the cities where it occurred, as well as and in the surrounding region. Namely, one may question if, as a consequence of hosting the events, were any change in the visitors' profile and motivations towards visiting those places. Amidst finding answers to these questions, these issues shall be addressed in this research, focusing on the 2012 Guimarães ECOC as a case study.

Since the turn of the century, studies regarding the ECOC have been performed on an international level, studies on the impacts of these mega-events. This is, mainly due to the result of the decision made by the European Commission requiring the host cities to deliver and hand in such studies, which became mandatory as of mid-2000 (Decision no. 1622/2006/EC). However, many of these studies mainly convey a political nature, focusing only the economic aspects (also due to these being easier to quantify than the socio-cultural ones – Langen and Garcia, 2009; Remoaldo, Duque & Cadima Ribeiro, 2015) and in the short term, usually during the lasting of the event. In fact, prior to 2012, the year in which Guimarães hosted the ECOC, looking at the 45 European Capitals of Culture (ECOC) that had previously organized, coverage of the before and after periods is quite rare. The periods investigated most are the ones during and after the hosting (Remoaldo et al., 2016).

Bearing in mind the interest of contributing to a better understanding of the purpose of organizing an event of this nature, a team of Portuguese researchers, along with a technician from the Municipality of Guimarães, decided to perform the assessment of the evolution of the profile of its visitors and their perceptions towards the attributes of Guimarães as a tourist destination. This investigation seeks to identify the changes that have occurred in the two aforementioned dimensions between 2010/2011 (before the mega-event) and 2015 (after the mega-event). For that, the first hypothesis tested being that there were no changes in the motivations and in the profile of visitors between 2010/2011 (before ECOC) and 2015 (three years after ECOC), i.e., the hosting of the ECOC lead to no significant change in the visitors' profile. The second hypothesis, assumed that the mega event led to attracting new segments of visitors.

This investigation, still in progress until the end of 2016, aims to contribute to better identifying the current position of Guimarães as a tourist destination, from the visitors' perspective. It also aims to help technicians, municipal and regional public authorities to design a more sustainable strategy for attracting more visitors and create customer loyalty towards the destination. As can easily be understand, customer loyalty is closely related to the satisfaction one gets from the experience of visiting a place and, therefore, from the destination´s features.

For the defined purpose, primary sources were used, namely, visitors were surveys in 2010/11 and 2015. The surveys were held in the Guimarães tourist offices and the respondents could take advantage of the availability of the technicians from the Municipality of Guimarães, that were working in the tourist offices to help fill in the questionnaires.

This article is structured in three sections, besides this Introduction, the Conclusions and the Recommendations. The first section deals with the motivations of cultural visitors and the characteristics of an ECOC and its expected legacies. The second section focuses on the analytical instruments used to capture the profile of visitors and their perceptions of the attributes of Guimarães as a tourist destination before and after the 2012 ECOC (in 2010/2011 and 2015). In the third section, the main results of the two surveys conducted are presented and analyzed. Finally, as mentioned, the main conclusions along with some policy recommendations.

2. Tourists` perceptions of the attributes of a destination, their profiles and the European Capitals of Culture

2.1. Visitors´ profile and motivations and the perceptions of the destination attributes

The perfect understanding of the processes which influence the motivation to travel is a critical factor for the successful development of tourism given it implies the perception of the consumer's needs and desires (Crompton, 1979; Beerli & Martin, 2004; Remoaldo et al., 2014a; Nikjoo & Ketabi, 2015; Adie & Hall, 2016). In the social sciences, the term "motivation" is associated to a situation that places the individual in a position where he is willing to spend a certain effort or money to achieve a certain goal (Dubois, 1990).

Since the 1960s, the literature has been concerned with tourist motivations as being fundamental for understanding tourist behaviors (Li, Zhang, Xiao & Chen, 2015). Withal, only since the 1970s have they been evaluated using factors associated with the individual, its context and with the supply provided by the destinations. These two dimensions behind the decision to taking a sightseeing tour, choosing a destination and providing internal and external forces (Uysal & Jurowski, 1994), were called push and pull factors. The model suggests that people are pushed to the decision to travel by internal forces and pulled by external forces that have to do with the attributes of a destination (Uysal & Jurowski, 1994).

In the late seventies Dann (1977), the first person to use these kind of factors, spoke about the push and pull factors focusing on the push ones, such as those stemming from “anomie” and “ego-enhancement” in the tourist themself. Crompton (1979) identified seven push and two pull factors. The push factors were: to escape to an environment perceived as routine; to explore new environments and self-assessment; to relax; prestige; return to the origins; the strengthening of family ties; and the facilitation of social interaction. The pull factors were the novelty and training/learning.

Following what has previously been said, this model assumes a distinction of the different factors that determine in each individual the need to leave their usual environment and performing a tourist journey and to fulfill the desire of his satisfaction need (push - Uysal & Hagan, 1993), and the factors identified in the destinations, which act as an attraction force to encourage one to travel (pull).

Uysal and Jurowski (1994) and Dias (2009) argue that this model results from the breakdown of travel decisions in two motivational forces: the first (push), is the one that makes the tourist decide to travel, and is related to the personal and/or social status of individuals; the second (pull) is an external force that is embodied in the attributes of a particular destination, which exert an attraction (more or less intense) on the visitor. This second force include both tangible resources (e.g., beaches, recreation facilities, cultural attractions) and the tourists' perceptions and expectations, (…) such as novelty, benefit expectation, and marketing image (Uysal & Jurowski, 1994, p. 844). This force is decisive in their choice, and acts through the perception held by the potential visitor to the destination. The “push and pull” model has generally been accepted in literature on tourist motivation since the late seventies (e.g., Uysal & Hagen, 1993; Uysal & Jurowski, 1994; Oku & Fukamachi, 2006; Mohamed & Othman, 2012). It is interesting to notice that this model continues, in our days, to be accepted (e.g., Mohamed & Othman, 2012; Li et al., 2015).

A possible interpretation of the role of these two motivational forces could be: firstly, due to the demand, the potential tourist makes the decision to travel; once the decision is made, based on the perceived attributes of the destinations, that is, those which are assumed to be able to satisfy the individual´s requirements, the potential tourist will then choose a particular destination (Crompton, 1979; Nikjoo & Ketabi, 2015).

From the empirical research conducted, there is also clear evidence that there tends to be a large difference between the motivation of traveling to a cultural destination or to one where the recreational motive is the main impelling force. For visitors who choose cultural destinations, the main motivation comes from education and from gaining knowledge (Kozak, 2002; Prayag & Ryan, 2011; Nikjoo & Ketabi, 2015).

As referred by Beerli and Martin (2004) and Vareiro (2008), demographic variables also influence the traveling motivations, where age, gender and the education level tend to be the most decisive ones. In turn, the pull factors are mainly related to the perception of the supply the visitor has and the destination´s ability to satisfy the consumer´s need. Obviously, being decisively influenced by the internal characteristics (attributes) of each person (Beerli & Martin, 2004). Baloglu and McCleary (1999) clarified this type of internal characteristic by highlighting the importance of the perceptual/cognitive evaluations and referring to the psychological (values, motivations and personality) and social factors (e.g., age, education, marital status). These factors are complemented by the stimulus factors such as, information sources (amount and type) and also previous experiences.

Despite the valuable contribution that empirical literature has provided for a better understanding of the phenomenon, the motivations of tourists are complex and many internal (i.e., of socio-psychological nature) and external factors influence people´s decision when the moment comes to choose a place to visit (Wall & Mathieson, 2006). All this reinforces the complexity of the competitive positioning of a destination, and, of course, of its planning and promotion also.

In the present paper and whilst analyzing of the destination aspect, the pull factor´s will be highlighted the most, i.e., those related to choosing the city of Guimarães. It is important to attain a good sound assessment of the attributes that prefigure Guimarães tourist image, along with how it´s perceived by its visitors, and the respective evolution between the two periods chosen for the present analysis. In this respect, the main aim is to confirm or to dismantle the maintenance of its image as a consequence of having hosting the 2012 ECOC, as one of its legacies.

As noted, the motivation to visit a destination stems from an individual decision, and the decision spreads from multiple factors, including the effort or financial resources that people are willing to spend on traveling, the needs felt and the consumer´s tastes and/ or preferences. However, as already noted at the beginning of this paper, there has been little research on the specific profile of visitors to places classified by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites, in particular regarding their socio-demographic characteristics (Adie & Hall, 2016). This occurs despite the relevance of this information for the definition of appropriate marketing campaigns, that is, being capable of simultaneously addressing the relevant segments of tourists and differentiating destinations in relation to their competitors.

This lack of attention given to tourists motivated by visiting historical and patrimonial sites contrasts with the perception held by many authors (e.g., Poria, Butler & Airey, 2004; Poria, Reichel & Biran, 2006; Chen & Chen, 2010; Yankholmes & Akyeampong, 2010) in which the main motivation for visiting these places is related to their characteristics as perceived by tourists and taking into account their own cultural heritage. Meaning that the decision of making the visit, arises more from the motivations and perceptions of the tourists rather than from the particular attributes of the destinations.

In the matter of choosing a cultural destination, and particularly those which exhibit the distinction of being officially recognized as World Heritage Sites, there is no surprise that the empirical literature available on the topic has identified a profile with a higher level of education than the average tourist, a more "mature" age and also an above average income (Light & Prentice, 1994; Silberberg, 1995; Kerstetter et al., 2001; Huh et al., 2006; Kima, Chengb & O'Leary, 2007; Pérez, 2009). However, there are, studies that raise the question of the validity of generalizing some of these attributes to the common World Heritage Site (Adie & Hall, 2016).

According to authors like Kima et al. (2007), Perez (2009), King and Prideaux (2010), and Remoaldo et al. (2014a), this type of visitor also tends to spend relatively more time at the destination, with women giving more preference to it than men.

This eventual gender segmentation relates to the importance that men and women give to the attributes of a certain destination, being reasonable to admit that “He” and “She” may value the same attributes differently (Meng & Uysal, 2008; Remoaldo, Vareiro, Cadima Ribeiro & Freitas Santos, 2014a).

Meanwhile, the predominance of women was only confirmed in one of the three World Heritage Sites, recently studied by Adie and Hall (2016). Being the case of the Archaeological Site of Bolubilis, in Morocco. In the other two analyzed, there was a predominance of men (the Independence Hall in the United States, and the Studenica Monastery Serbia).

Concerning the average age of the visitor, attention should be drawn to the fact that lately, the group of cultural tourists, have diversified, attracting an increasing amount of younger visitors (Richards, 2004; Richards, 2007 cited by Adie and Hall, 2016; Nguyen & Cheung, 2014; Remoaldo et al., 2014a), in comparison to what tended to be found in more remote empirical literature. In this regard, one may add that, in the empirical study of Adie and Hall (2016), the dominance of the "mature" age group was not confirmed in the three places analyzed, giving rise to one believing it could be due to the nature of the legacy, i.e., with its specific symbolism, alongside with the local culture and the socio-political aspects.

Another feature also focused on by some studies, refers to the nationality of the tourist, which generates the idea that, in the case of visiting World Heritage Sites, international tourists tend to prevail (Nguyen & Cheung, 2014). This result has also been questioned by the empirical research of Adie and Hall (2016), as they both found, the predominance of national or foreign visitors to the sites studied.

2.2. The ECOC and its legacies

Events can be assumed as key elements either to the country of origin (motivating tourism) or to the territory of destination, because they contribute to the development and promotion of marketing strategies of most destinations (Getz & Page, 2016). This new approach has meant that some of the traditional features, such as being ephemeral and occasional, of mega-events has been lost. Instead, they became a regular urban practices (Steffani, 2011). Since the 1990's, a clear and systematic competition to the hosting of mega-events, which is thought contributes to the development of cities has emerged. (Steffani, 2011). Thus, mega-events have become an important experience of being modern and many council decision-makers have chosen urban tourism, mediated by the organization of certain types of mega-events, as a key tool to start urban regeneration. ECOC are one of the examples that can used to transmit and demonstrate this view point.

In terms of scale and budget, the European Capitals of Culture (ECOC) are the most relevant and risky European Union project that takes place in Europe every year (European Commission, 2009a). If a list of events is looked at, it is the third most important mega-event taking place in the European Continent, only after the Olympic Games and the World and the European Football Championships (Van Heck, 2011). Despite some controversy on the term “mega-event” and its use to classify the European Capitals of Culture, throughout this this investigation, the option to use the term has been chosen due to several characteristics, namely: firstly, for it being a large scale and sporadic event, lasting up to a year; also, being of international nature in terms of its media coverage, meaning a higher number of expected participants; requiring the involvement of a significant amount of human, financial, communication and cultural resources and its scheduling being prepared in advance; and, finally, if delivered efficiently, it may change the hosting city´s image (Gursoy, Chi, Ai, & Chen, 2011; Agha & Taks, 2015).

Nowadays, it is looked at by the European Commission as being an international event endowed of prestige and going through a mature phase, which takes place during a year and has achieved a comfortable consolidated position in the general cultural calendar (European Commission, 2015). As also assumed by the European Commission (European Commission, 2015), in the thirty-one years of its existence, it has given a surmounting contribution to the European cultural wealth, having been hosted by more than 50 cities.

This event is held based on the essential role cities take in what regards cultural issues, which was officially created by a European Resolution dated from 1985 (Resolution of the Ministers Responsible for Cultural Affairs Concerning the Annual Event “European City of Culture” - Doc. 7081/84). In that Resolution the concept of “Cultural European City”) was used for the first time in official documents. It was then that it was established that such an event would last for around one year. The city hosting the event in a certain year should promote a program of events envisaging to underline its contribution to the common cultural heritage and welcome visitors and artists from the other European member states (European Commission, 2009b). The first European Capital of Culture (ECOC) took place in that very same year (1985), in Athens.

Since then, many cities found the hosting of an ECOC an opportunity mostly for, the renewal of its urban tissue and acquiring national and international visibility, therefore contributing to its promotion as a tourist destination. The opportunity to develop and to offer a more diversified and sustained cultural supply in the post event period has also been underlined.

The year 1990 is to be remembered as one of change, in what concerns the hosting of the ECOC by Glasgow, turning a once, non traditional cultural destination into one. The urban rehabilitation that took place and the enhancement of the city´s image as a cultural destination were elements included in the submitted application.

The economic impacts of hosting the ECOC by Glasgow were assessed as extremely positives, having the city benefited from the increase in the amount of visitors, and, of course, from the expenses incurred by them (Freitas Santos, Remoaldo, Cadima Ribeiro & Vareiro, 2011). Including also, as an ECOC legacy, an increase in the supply of various cultural activities (Myerscough, 1991, cited by Richards, 2000).

The concept of “legacy”, that is, the long term impacts verified within the urban and regional tissues (Hiller, 2003; Müller, 2015) which justify (or should justify) the high level of expenses incurred in hosting of mega-events, will be assumed as such in this paper. As a result of this, the word “legacy” regards the post event period, as claimed by Hiller (2003). Generally speaking, this concept is linked to positive changes experienced by the hosting city and, usually, tends to be expressed as something tangible.

In order to be elected to host the European Capital of Culture event, a city needs to be willing to modify its ordinary management routines and redefine the goals of its planning. Namely, it should envisage to implement policies that will enhance its qualification as a cultural center and, as such, help it to be successful in the application submitted. In the assessment of the success gained from hosting a mega-event (an ECOC or other king of event), cities emphasis more and more what will happen in the post event period, that is, the expected long term impacts, that is, the legacies (Hiller, 2003).

In the assessment of the impacts of mega-events, studies performed do not often include, both, the effects felt before and after their hosting (Remoaldo et al., 2016). The impacts incurred during and after the event have attracted researchers more.

In the case of the 2012 ECOC, hosted by Guimarães, several commissioned reports were produced by an integrated team of researchers from the University of Minho, with their results published in 2012 and 2013 (Universidade do Minho, 2012a, 2012b, 2013a, 2013b). Using both quantitative and qualitative methods, the economic impacts were assessed as well as the visibility the event received in media coverage and in social networks.

The results attained were qualified as positive, worth mentioning the increase in more than 50% in foreign visitors when comparing with previous years. In turn, there was an increase of around 300% in Portuguese visitors (Universidade do Minho, 2013b).

However, the previously mentioned studies were centered on the ongoing period of the mega-event, with even several stakeholders being considered (such as, tourists, youth residents, local cultural actors and local retail). Going beyond those results and looking at the medium to long term ECOC legacy regarding attracting tourists, is one of the main aims of the research presently being carried out.

3. Methodology

The methodology used in this research is of a quantitative nature and envisaged, as was claimed, on the one hand, to assess the evolution of the visitors` perceptions of the characteristics of Guimarães as a tourist destination and, on the other hand, to verify the preservation or the changing of their profile. By doing this, indirectly, we have tried to capturing the impacts felt by hosting the 2012 European Capital of Culture by the city in the before mentioned dimensions is attempted.

It must be underlined that only some years after hosting an event of such nature and magnitude will one be able to access all of its impacts, that is, just then can one really provide a complete inventory of the effects and measure the costs and benefits brought on by it (Remoaldo et al., 2016). This has to do with the need to wait for the conclusion of the equipment planned for the event and which, in some cases, is only concluded shortly after its closure. Additionally, only a few years later, can the economic sustainability of the equipment built be verified.

These reasons are what led to conducting the survey only 3 years after the Guimarães ECOC taking place.

As mentioned above, to attain the aims, primary sources were used based on the implementation of two surveys: the first in 2010/2011 and the second in 2015.

The questionnaire used suffered a few changes between 2010/2011 and 2015, namely: the 2015 version contained 22 questions instead of 10, as in the 2010/2011. This envisaged to capture the changes which had occurred in the destination´s supply. In this paper, only the questions considered comparable and directly regard the issue under analysis were taken into account.

The survey conducted had both Portuguese and English versions and before being applied, in both periods (2010 and in 2015), pre-tests were conducted. The pre-tests allowed for the assurance of the internal and external consistence of the included questions and to assess the time needed to fill them in. Based on the pre-tests, minor changes in their design were made, namely to guarantee an easier interpretation of a number of questions raised.

The survey, self-administered, was applied in the tourism offices of the city (two in 2010 and one in 2015), and included three sections. The first section was related to the features of the visit made to the north of Portugal. The second section (which included three questions in 2010/2011 and fourteen in 2015) regarded the attributes of Guimarães and the eventual recommendation to visit the destination. The last section was devoted to the socio-demographic features of the respondents, which included five questions in the 2010/2011 version and seven in the 2015 one (e.g., gender, age, education level, civil status, place of residence).

In some of the questions, a five level Likert scale was used, ranging from expressing complete disagreement (level 1) to complete agreement (level 5). In the analysis of the data collected, SPSS statistical software, version 23th, was used, and an approach following 4 steps was chosen: first, the socio-demographic features of the visitors in both periods (before the ECOC and after it) were compared in order to assess their profile; in a second phase, the main destinations in the north of Portugal chosen were identified, as well as the visitors´main motivations behind their choice in visiting Guimarães; thirdly, the attributes of Guimarães perceived by the visitors in each specific period were ranked; lastly, chi-square (X2) and t tests were performed to evaluate the existence of statistical differences between the attributes perceived by the visitors in 2010/2011 and in 2015.

Guimarães is a middle size city located in the northern part of Portugal. With its distinctive 10th-century castle, it is considered to be the cradle of the Portuguese nation. The city is full of many traditional buildings dating from the 15th to the 19th centuries.

The city and the region in which it is included in (the Minho) have a long manufacturing based tradition, mainly in, activities such as textiles, clothing and footwear. The tourism industry has developed over the last two decades and has been playing an increasing complementary role in employment and as an income generator.

The city is located 50 km from Oporto and less than that from the Oporto international airport. The hosting of the 2012 European Capital of Culture and its certification by UNESCO, in 2001, as a World Heritage Site has promoted its external visibility and has been shaping the city image.

Despite the increasing number of visitors, their average stay is quite short (less than 2.0 nights). With regards to the proportion of foreign guests, Guimarães falls below the national average, with the visitors coming from, besides Portugal, mostly, from the European Union countries, more specifically Spain and France (Universidade do Minho, 2013b; Remoaldo et al., 2014b).

4. Visitors profile and the perceptions of Guimarães´ tourist attributes before and after the 2012 ECOC

4.1. Brief description of the samples

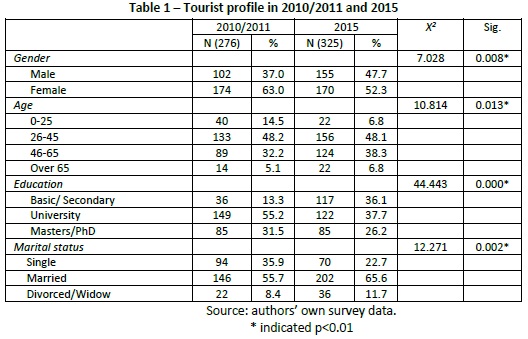

Taking into account the main socio-demographic variables, Table 1 summarizes the profiles of the survey respondents by visit date (2010/2011 and 2015).

The differences in the characteristics of the respondents were analyzed using chi-square tests. These tests showed statistically significant differences in all variables considered. Thus, meaning a greater balance between men and women who visited the city was verified in 2015 compared to what had occurred in 2010/2011, where we found a high predominance of females. Even after this development, more women than men still visit the destination, remaining consistent with the empirical results presented by Kima et al. (2007), Pérez (2009), King and Prideaux (2010), and Remoaldo et al. (2014a). These results contrast, however, with the ones found by Adie and Hall (2016) in two of the Humanity Cultural Heritage sites they studied.

A decrease in the amount of tourists aged from 0 to 25 years old and an increase in those aged from 46 to 65 was also identified. This result, together with the data cited above about to the reduction in the number of female visitors, indicates that a change in the visitor profile was verified along the period analyzed.

This trend may suggest that older visitor segments show a more favourable perception of the destination. Normally integrated in the mentioned segments are people characterized with greater financial availability and who are more demanding with regards to the quality of the destination, which is in line with what can be found in empirical literature. Given a destination classified as Cultural Heritage by UNESCO is being referred to, this result meets the expectations hoped for (Light & Prentice, 1994; Silberberg, 1995; Kerstetter, Confer & Graefe, 2001; Kima et al., 2007, Pérez, 2009; Remoaldo et al., 2014a).

Contradictorily, in 2015, there was an increase in the number of visitors endowed with lower schooling levels, although higher levels of education visitors still showing more dominance, as generally observed in the empirical literature available (see Table 1). This increase may be linked to a greater awareness of the destination, allowing for it to penetrate a broader range of visitors. Also adding that, from one period to the next, there was an increase of married visitors and a decline in single ones, which, to some extent, can be related to the reduction in the relative weight of the younger visitors´ group.

4.2. Visited destinations and visitors´motivations

In order to obtain more information on major destinations included in the trip taken, respondents were asked which destinations they had visited or planned to visit in the context of the trip they were taking.

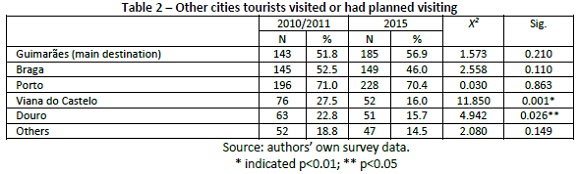

Oporto (53 km from Guimarães and the main city in the Northern Region of Portugal) emerged as the main destination (indicated by 71% of the respondents in 2010/2011 and 70.4% in 2015). The main circuit made included Oporto-Guimarães-Braga (this last city is 25 km from Guimarães and 45 km from Oporto). This fits into one of the tourist segment characteristics of the Northern Region – the cultural touring. However, there has been an increase in the amount of visitors who choose Guimarães as the main destination and a decline in visitors that also included Viana do Castelo and the Douro in their trip itinerary (see Table 2). This reinforcement of Guimarães as the main destination may also be seen as a result of the higher reputation acquired by a Guimarães destination in the regional context along the period.

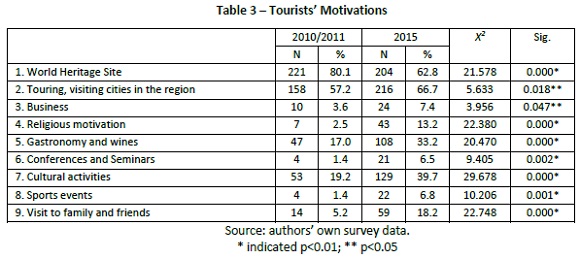

The second question raised aimed to identify the motivations behind choosing Guimarães. The historic center of Guimarães, which, as mentioned, is classified by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, emerged in the responses collected in 2010/2011 as the main motivation for visiting the city (mentioned by 80.1% of the respondents), followed by Touring (visiting a certain amount of neighboring cities in the region), which was reported by 57.2% of respondents in 2010/2011. These two reasons remained the major travel motivations in 2015, but their relative position reversed, and the gap previously observed in terms of preference among them blurred.

To better understand this result, one must relay that in recent years, Portugal as a whole and the north of Portugal in particular, witnessed significant increases in the number of visitors. The increased demand has led to more tour packages available in the region, with Touring as a clear highlight.

Table 3 also shows the increase in the percentage of motivations associated with Cultural Activities, which rose from 19.2% in 2010/11 to 39.7% in 2015, and Gastronomy, which registered a significant increase from 17.0% in 2010/11 to 33.2% in 2015.

Consequently, it can be concluded that there was an evident strengthening of the perception of the cultural dynamics of the destination, which somehow may result from having hosted the 2012 ECOC and from the gained visibility this event has gave to this dimension of the tourism supply in the city. Results like these strengthen the guiding idea of European institutions establishing and continuing to backup this event, being consistent with the findings in other studies, as outlined by Richards (2000) and Freitas Santos et al. (2011). As we got p<α for the tourists' motivations, on a whole (Table 3), the hypothesis that the reason for choosing Guimarães is the same for both the 2010/2011 visitors and for the 2015 ones can not be accepted (i.e., the choice of any of the reasons claimed cannot be disassociated from the period under analysis). For example, the percentage of respondents who chose Guimarães for it being a World Heritage Site was significantly higher in 2010/2011 than in 2015 (80.1% versus 62.8%). In the case of the Touring, Gastronomy and wines and Cultural Activities, the percentage of respondents was significantly higher in 2015.

Similar to what has already been noted regarding the profile of visitors in both periods under analysis, results show that tourists' motivations appear to be somewhat contradictory. In fact, visitors' motivation linked to UNESCO´s classification of the historic center of the city as a world cultural heritage decreased in favor of something that falls in the banal context of recreation and leisure tourism (touring). It is equally true that the city´s tourism offer seems to be perceived as being broader and more complex than initially perceived.

4.3. The perceived attributes of Guimarães

The third question raised corresponds to the main question of the survey (Please indicate to what extent you agree/disagree with the attributes that, in your opinion, best describe the city of Guimarães), comprising of 14 attributes (common to both questionnaires) based on a five-point Likert scale (1 = total disagreement, 2 = disagreement, 3 = neutral, 4 = agreement; 5 = full agreement).

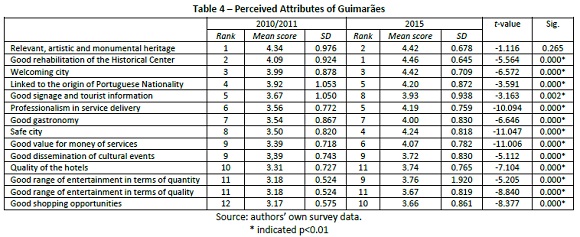

Table 4 shows the ranking of the 14 perceived characteristics/attributes according to visit date. Generally speaking, a larger difference in the way both groups ranked the perceived attributes of the destination was not identified. Both, the respondents of 2010/2011 and the ones of 2015 declared that the city's most important attributes were its “Relevant artistic and monumental heritage", "Good rehabilitation of the historical center,” and it being "Welcoming city." Here again and in line with the visitor profile identified its historical and cultural heritage emerges as a “reference”, as previously commented.

In relation to this issue, it may be considered worth recapping something that was emphasized in the review of the literature, namely that the main reason for visiting places like the one analyzed in the present research (Guimarães) relates largely to the features perceived by tourists and that stem from their own cultural heritage (Poria, Butler & Airey, 2004; Poria, Reichel & Biran, 2006; Chen & Chen, 2010; Yankholmes and Akyeampong, 2010). The current study does not provide any further detail on the nationality of the visitors however, following official data available, one can always state that, apart from the Portuguese, the main demanding markets have been Spain (in Spain, Galicia, a neighboring territory), France, and Brazil.

The attributes identified as the least important were those related to the “Good range of entertainment in terms of quality”, the “Quality of the hotels”, and the “Good range of entertainment in terms of quantity”.

After ranking the perceived attributes of Guimarães, the means attained in each visitor groups surveyed in 2010/2011 and 2015, following the visitors' answers, were compared (see Table 4). The results of t tests indicated that the 2015 visitors showed higher values in all items, when confronted with the ones from 2010/2011, showing significant statistical differences in all but one, namely “Relevant artistic and monumental heritage”.

Considering all the t tests performed, as an overall result, it was concluded that the 2015 visitors seemed more satisfied with the attributes of the city. Therefore, one can reason that there is leeway for improvement in respect to the city´s image, as perceived by its visitors. In this facet, worth mentioning is the emphasis made in the perception of the destination being a safe city, especially at a moment where safety plays an important and increasing role in the decision making process when electing a destination. It is also important to stress the significant increase experienced by the attributes “Good value for services”, “Professionalism in service delivery”, and "Good range of entertainment in terms of quality". However, despite this improvement and considering the average values identified, place for further improvement can and should be aimed at. In summary, the findings obtained from the empirical research left no doubt that the city of Guimarães faces an ongoing change regarding its visitor`s profile, and there is a notorious evolution of the city´s perceived attributes, that is, in the perceived pull factors associated to its visit. In this context, it is important to underlining that the reputation the destination has achieved, expressed by a significant increase in the amount of visitors (in which, definitely, the hosting of the 2012 European Capital of Culture 2012 has added a major contribution), when assessed in terms of level of schooling, has resulted in a downgrade of tourists. That is, the path towards mass tourism seems to be made at the expense of losing its identity as a typical cultural destination. This interpretation is supported on the idea that these new segments of visitors are, hypothetically, less culturally motivated than the ones that set up the visitor profile of the destination, in the first decade of the twenty-first century. This is consistent with the second hypothesis raised, being that, the mega event gave way to the capturing of new visitor segments.

The less critical dimension of this path results in the increase of the share of older visitors, which are commonly linked to groups with higher incomes and are more stringent with regards to the destination´s quality (cultural qualities and/ or attributes) of the destination. Also worth being highlighted is the increased perception of the city being enriched with a wider portfolio of products than compared to the first phase of its launching as a tourist destination. To the already strong and solid image of Guimarães shaped by the label of having a historical center classified as a World Heritage Site, other less tangible attributes, such as gastronomy, entertainment, and cultural events, have been joined.

5. Conclusions and recommendations

As already mentioned, this paper envisions to assess the evolution of Guimarães vistor´s profile between 2010/11 and 2015, as well as their perceptions of the destination´s tourist attributes. Admitting, at least partially, that a few changes could have verified in, both, the tourists profile and their perception of the attributes of the city due to the hosting of the 2012 ECOC. The comparative analysis held between the 2010/11 data (before hosting the mega-event) and the 2015 data (post hosting) served as a starting point.

Thus, contributing to understand a clearer position of the destination at the present time, according to the visitor's approach, and to help the tourism actors in the design of a more sustainable and consistent strategy in order to attract visitors and to commit them to the destination is what is intended. Visitors' satisfaction will always be the result of experiencing a good trip and, in turn, closely relates to the destination´s perceived characteristics.

With reference to the visitor profile that elects Guimarães for their holiday or short break stay, it can be concluded that the demand has attained a more balanced situation regarding the presence of men and women, although women continue to be the majority amongst visitors. At the same time, the destination experienced a decrease in visitors aged between the 0 and 25 and an increase in those aged between 46 and 65 years of age.

Another feature of the evolution identified relates to the increase of tourists endowed with lower schooling levels, when comparing the data between 2010/20011 and 2015. In any case, the predominant cohort still being the visitors with higher schooling levels. Additionally, the data has shown an increase in married visitors.

Within this profile some of the characteristics which are normally associated with cultural/heritage destinations along with others that point out, that the destination is attracting segments of tourists that are less committed to educational and cultural tourist experiences, can be depicted.

Speaking of the destination´s attributes, and following the results of the surveys conducted, either in 2010/2011 or in 2015, of the most valued were: “Relevant artistic and architectural patrimony”; “Good rehabilitation of the historical center; and “Welcoming city”. Keeping in mind the results of the t tests performed, one can conclude that the 2015 visitors to Guimarães showed they were more pleased with its attributes than those in 2010/11, prior to the hosting of the ECOC.

If this result is looked at as being an output of the mega-event, then it can be seen as a positive legacy. Worth mentioning also is the emphasis made in the perception of the destination being a safe city, especially at a moment where safety plays an important and increasing role in the decision making process when electing a destination.

Remarking on the issue of the motivations behind the choosing of a particular destination, something closely related with the image perceived and, thus, with the attributes that contribute to it, important to keep in mind that being a World Cultural Heritage (meaning the historical center of the city) showed in 2010/2011 to be the main motivation for the visit (receiving 80.1% of the survey respondents), followed by Touring, receiving 57.2% of mentions. With Touring coming in first place in the motivation ranking in 2015, showing a change from the previous rank.

From the empirical data obtained regarding tourists` motivations, one should also underline, the noted increase in the mentions relating to the Local Gastronomy, which shifted from 17.0% in 2010/11 to 33.2% in 2015, and the motivations connected with Cultural Activities, which registered a significant increase, going from 19.2% in 2010/2011 to 39.2% in 2015. Perhaps the notorious increase in the notoriety achieved by the Green Wines (table wines characteristically of the Minho region) may have added in some way to this result. The cultural and multifunctional equipment's built during the year of the ECOC (2012) like the “Plataforma das Artes e da Criatividade” (Platform of Arts and Creativity), which was an important investment and which has permanent and periodical expositions, could also have contributed to the higher significance of its cultural activities. This equipment could complement and strengthen the cultural activities that existed prior to 2012 like the “Centro Cultural Vila Flor” (Vila Flor Cultural Centre) inaugurated in 2005 and still the main cultural facility, however focused more on musical events. The inauguration in the first semester of 2016 of the “Casa da Memória” (House of Memory), which is a legacy of Guimarães 2012 ECOC, is an anchor of Guimarães´History and Culture in its, historical, social, cultural, economic and experiential perspectives, also reinforcing and to strengthening the city´s cultural activities. It is known as a place of meeting, sharing and reflection of Guimarães´ roots, traditions and memories.

From everything that has been exposed throughout the present research, it is possible to sum up that the hosting of the ECOC and the visibility conferred to the specific dimension (culture) of the tourist supply has contributed to the perception of it being endowed as a culturally dynamic destination. In fact, when one mentions the gastronomy, this also demonstrates the cultural dimension of a territory and, thus, of a community that is invoked whilst assuming a different feature in terms of arts or architecture. All of them opening doors for new experiences.

All together, we are confronted with a change in the destination´s visitor profile and a notorious evolution of the perceived attributes of the city. One of the less positive features that can be extracted from the notoriety achieved, is expressed in the increase in the number of visitors, although attracting a segment of tourists said to be less qualified in average terms, if we look at their level of schooling. Surely, the hosting of the 2012 European Capital of Culture has strongly contributed to that enhanced visibility.

Hence, one can convey that the direction towards mass tourism which the destination is developing seems to endanger its identity as a typical cultural destination, based on the new segment of visitors who are less culturally motivated. The less critical dimension of that direction mentioned results from the increase in the segment of older tourists and even more important and quite significant the maintenance of the more highly qualified ones. This tourists' cohort usually is endowed of greater cultural motivation.

Keeping in mind these results, the public authorities in charge of the planning and managing of the tourist destination face the dilemma of working towards continuing to enhance the amount of visitors or to preserving the city´s profile, remarkable for its historical, cultural and symbolic legacy. The first option means admitting to having a tourist offer that is less centered on its cultural and dynamic attributes. In other words, the option for choosing a destination is assuming a less singular profile and is more addressed to mass consumption, or risking, mostly, on the notoriety of the city´s tourism based on its patrimonial legacy and its general cultural dynamics.

If the option chosen is this last one, there is the continuous need to insist on increasing its cultural supply and provide visitors with in depth cultural experiences, keeping in mind the attempt of gaining a segment of demand which is strongly committed towards cultural experiences but, surely, more demanding in what concerns the quality of the service provided regards. If this be the strategy to adopt, it is important that, the image to be promoted is coherent with thought, in order to prevent attracting tourists unsatisfied with the experience available.

This present research suffers several limitations, the first one resulting from the dimension of the sample used in the survey applied in 2010/11: although covering all the tourist seasons and is representative of the visitors' universe, as identified in previous inventories conducted by the Municipality of Guimarães, it could have benefited more if the numbers had been greater.

Another limitation, regarding the 2015 data comes from the option made of only inquiring the visitors in the city´s existing tourism office (only one, contrary to the situation in previous years, where there two). This fact may have benefited foreigners' visitors as they seem to use the tourism office in larger shares than national visitors do. Therefore, one can conclude that the probability of inquiring foreigner visitors is larger than the probability of inquiring Portuguese ones. This interpretation of data is supported by the results attained, where more than two thirds of the survey respondents are foreigners. Thus, the empirical results will better portray the perceptions held by this group of visitors of the city´s attributes, along with their socio-demographic profile. Nevertheless, this was a better solution than the one chosen by the same team in previous years, i.e., in the more symbolic sites of the city, which revealed that tourists had more time to answer the survey in the tourism office.

REFERENCES

Adie, B. A., & Hall, C. M. (2016). Who visits world heritage? A comparative analysis of three cultural sites”. Journal of Heritage Tourism, DOI: 10.1080/1743873X.2016.1151429. [ Links ]

Agha, N., & Taks, M. (2015). A theoretical comparison of the economic impact of large and small events. International Journal of Sport Finance, 10(3), 103-121. [ Links ]

Baloglu, S., & McCleary, K. (1999). A model of destination image formation. Annals of Tourism Research, 26 (4), 868-897. [ Links ]

Beerli, A., & Martin, J. M. (2004). Tourists' characteristics and the perceived image of tourist destinations: a quantitative analysis – a case study of Lanzarote, Spain. Tourism Management, 25(5), 623-636. [ Links ]

Chen, C., & Chen, F. (2010). Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tourism Management, 31(1), 29-35. [ Links ]

Crompton, J. L. (1979). Motivations for pleasure vacations. Annals of Tourism Research, 6 (4), 408-424. [ Links ]

Dann, G. (1977). Anomie, Ego-enhancement and Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 4(4), 184-194. [ Links ]

Dias, F. (2009). Visão de síntese sobre a problemática da motivação turística. Revista científica do ISCET, No. 1, 2ª série, 117-143. [ Links ]

Dubois, B. (1990). Compreender o consumidor. Lisboa: Dom Quixote, [ Links ]

European Commission (2009a). European Capitals of Culture: the road to success. From 1985 to 2010. Luxembourg: European Commission.

European Commission (2009b). Ex Post evaluation of the European Capital of Culture event 2007 (Luxembourg and Sibiu) and 2008 (Liverpool and Stavanger). Report from the Council, the European Parliament and the Committee of the Regions, 689, Brussels.

European Commission (2015). European Capitals of Culture: 30 years. Luxembourg: European Commission. [ Links ]

Freitas Santos, J., Remoaldo, P. C., Cadima Ribeiro, J., & Vareiro, L. (2011). Potenciais impactos para Guimarães do acolhimento da Capital Europeia da Cultura 2012: uma análise baseada em experiências anteriores. Revista Electrônica de Turismo Cultural, 5(1), 56-72. [ Links ]

Getz, D., & Page, S. J. (2016). Progress and prospects for event tourism research. Tourism Management, 52, 593-631. [ Links ]

Gursoy, D., Chi, C. G., Ai, J., & Chen, B. T. (2011). Temporal Change in Resident Perceptions of a Mega-event: The Beijing 2008 Olympic Games. Tourism Geographies, 13(2), 299-324. [ Links ]

Hiller, H. H. (2003). Toward a Science of Olympic Outcomes: The Urban Legacy. In Moragas, M., Kennett, C., & Puig, N. (Eds.). The Legacy of the Olympic Games 1984-2000 (pp 102-109). Lausanne: International Olympic Committee. [ Links ]

Huh, J., Uysal, M., & McCleary, K. (2006). Cultural/heritage destinations: Tourist satisfaction and market segmentation. Journal of Hospitality & Leisure Marketing, 14(3), 81-99. [ Links ]

Kerstetter, D. L., Confer, J. J., & Graefe, A. R. (2001). An exploration of the specialization concept within the context of heritage tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 39 (3), 267–274. [ Links ]

Kima, H., Chengb, C.-K., & O'Leary, J. (2007). Understanding participation patterns and trends in tourism cultural attractions. Tourism Management, 28(5), 1366-1371. [ Links ]

King, L. M., & Prideaux, B. (2010). Special interest tourists collecting places and destinations: A case study of Australian World Heritage Sites. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 16(3), 235–247. [ Links ]

Kozac, M. (2002). Comparative analysis of tourist motivations by nationality and destinations. Tourism Management, 23(3), 221-232. [ Links ]

Langen, F., & Garcia, B. (2009). Measuring the Impacts of Large Scale Cultural Events: A Literature Review. Liverpool: Impacts 08. [ Links ]

Li, M., Zhang, H., Xiao, H., & Chen, Y. (2015). A grid-group analysis of tourism motivation. International Journal of Tourism Research, 17(1), pp. 35-44.

Light, D., & Prentice, R.C. (1994). Who consumes the heritage product? Implications for European heritage tourism. In Ashworth, G. J., & Larkham, P. J. (Eds.). Building a new heritage: Tourism, culture and identity in the New Europe (pp. 90-116). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Meng, F., & Uysal, M. (2008). Effects of gender differences on perceptions of destination attributes, motivations, and travel values: an examination of a nature-based resort destination. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16(4), 445-466. [ Links ]

Mohamed, N., & Othman, N. (2012). Push and Pull Factor: Determining the Visitors Satisfactions at Urban Recreational Area. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 49, 175-182. [ Links ]

Müller, M. (2015). What makes an event a mega-event? Definitions and sizes”, Leisure Studies, 34(6), 627-642. [ Links ]

Nguyen, T. H. H., & Cheung, C. (2014). The classification of heritage tourists: A case of Hue city, Vietnam. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 9 (1), 35–50. [ Links ]

Nikjoo, A. H., & Ketabi, M. (2015). The role of push and pull factors in the way tourists choose their destination. Anatolia, 26(4), 558-559. [ Links ]

Oku, H., & Fukamachi, K. (2006). The differences in scenic perception of forest visitors through their attributes and recreational activity. Landscape and Urban Planning, 75, 34-42. [ Links ]

Pérez, X. (2009). Turismo Cultural. Uma visão antropológica. Tenerife: Colección PASOS. [ Links ]

Poria, Y., Butler, R., & Airey, D. (2004). Links between tourists, heritage, and reasons for visiting heritage sites. Journal of Travel Research, 43(1), 19-28. [ Links ]

Poria, Y., Reichel, A., & Biran, A. (2006). Heritage site management: motivations and expectations. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(1), 162-178. [ Links ]

Prayag, G., & Ryan, C. (2011). The relationship between the push & pull attributes of a tourist destination: the role of nationality. An analytical qualitative research approach. Current Issues in Tourism, 14(2), 121-143. [ Links ]

Remoaldo, P. C., Vareiro, L., Cadima Ribeiro, J., & Freitas Santos, J. (2014a). Does gender affect visiting a World Heritage Site?. Visitor Studies, 17(1), 89-106.

Remoaldo, P. C., Cadima Ribeiro, J., Vareiro, L., & Freitas Santos, J. (2014b). Tourists' perceptions of world heritage destinations: The case of Guimarães (Portugal). Tourism and Hospitality Research, 14(4), 206-218.

Remoaldo, P. C., Duque, E., & Cadima Ribeiro, J. (2015). The environmental impacts perceived by the local community from hosting the ‘2012 Guimarães European Capital of Culture'”. Ambiente y Desarrollo, 19(36), 29-42. [ Links ]

Remoaldo, P. C., Vareiro, L., Cadima Ribeiro, J., & Freitas Santos, J. (2016). Residents' perceptions on impacts of hosting the Guimarães 2012 European Capital of Culture: comparison of the pre and post periods. In Matias, A., Nijkamp, P., & Romão, J. (Eds.).Advances in Tourism Economics, Impact Assessment in Tourism Economics (pp. 229-246). Berlin: Springer International Publishing AG. [ Links ]

Richards, G. (2000). The European cultural capital event: strategic weapon in the cultural arms race?. Cultural Policy, 6 (2), 159-181. [ Links ]

Richards, G. (2004). The festivalisation of society or the socialisation of festivals: the case of Catalunya. In Richards, G. (Ed.). Cultural Tourism: globalising the local – localising the global (pp. 187-201). Tilburg: ATLAS. [ Links ]

Silberberg, T. (1995). Cultural tourism and business opportunities for museums and heritage sites. Tourism Management, 16 (5), 361-365. [ Links ]

Steffani, A. (2011). A la carte urban policies. Mega-events: from exceptionality to construction of ordinary planning practices. A look at Italy: case study of the 2006 Winter Olympic Games in Turin. Science – Future of Lithuania, 3(3), 23-29. [ Links ]

Universidade do Minho (2012a). Guimarães 2012: Capital Europeia da Cultura. Impactos Económicos e Sociais. Relatório Intercalar, maio de 2012. Guimarães: Fundação Cidade de Guimarães.

Universidade do Minho (2012b). Guimarães 2012: Capital Europeia da Cultura. Impactos Económicos e Sociais. Relatório Intercalar, outubro de 2012. Guimarães: Fundação Cidade de Guimarães.

Universidade do Minho (2013a). Guimarães 2012: Capital Europeia da Cultura. Impactos Económicos e Sociais. Relatório Intercalar, fevereiro de 2013. Guimarães: Fundação Cidade de Guimarães.

Universidade do Minho (2013b). Guimarães 2012: Capital Europeia da Cultura. Impactos Económicos e Sociais. Relatório Executivo. Guimarães: Fundação Cidade de Guimarães.

Uysal, M., & Hagan, L. A. R. (1993). Motivations of Pleasure Travel and Tourism. VNR'S Encyclopedia of Hospitality and Tourism. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. [ Links ]

Uysal, M., & Jurowski, C. (1994). Testing the push and pull factors. Annals of Tourism Research, 21(4), 844-846. [ Links ]

Van Heck, I. (2011). The European Capital of Culture: aims, expectations, outcomes and cooperations in relation to this high profile mega event, Nijmegen. Radboud University Nijmegen – Nijmegen School of Management, Master Thesis – Economic Geography.

Vareiro, L. (2008). O Turismo como Estratégia Integradora dos Recursos Locais: caso da NUT III Minho-Lima. Tese de Doutoramento em Ciências Económicas, Universidade do Minho, Braga. [ Links ]

Wall, G., & Mathieson, A. (2006). Tourism: change, impacts and opportunities. London: Pearson-Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Yankholmes, A., & Akyeampong, O. (2010). Tourists' Perceptions of Heritage Tourism Development in Danish-Osu, Ghana. International Journal of Tourism Research, 12(5), 603-616. [ Links ]

Received: 10 January 2017

Revisions required: 12 March 2017

Accepted: 12 July 2017