Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.13 no.4 Faro dez. 2017

MANAGEMENT: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Knowledge transfer exchange and dynamic Guanxi in Chinese universities

Transferencia de conocimiento y Guanxi dinámico en universidades Chinas

Antonio Padilla-Meléndez*, Zhenxing Li**

*Facultad de Estudios Sociales y del Trabajo, University of Malaga, Av Francisco Trujillo Villanueva, s/n, 29071 Malaga, Spain, apm@uma.es

**Facultad de Estudios Sociales y del Trabajo, University of Malaga, Av Francisco Trujillo Villanueva, s/n, 29071 Malaga, Spain, zhenxing.li@uma.es

ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the relevance of guanxi (关系) as a cultural factor in knowledge transfer exchange (KTE), on an individual level, in the Chinese university-industry context. Adopting a qualitative case-study approach, with data from 50 interviews, this work brings a fresh view to the role of social networks as a cultural value in university researchers' participation in KTE activities. In addition, this paper breaks the traditional linear view toward guanxi. Instead, it adopts a dynamic, dialectical, and holistic perspective towards the role of guanxi in KTE processes in the context of Chinese universities. It has been found that during the KTE process, guanxi networks should be balanced with the appropriate infrastructure, qualified staff, and financial investment to obtain successful outcomes. This study enriches the existing literature on the determinants that affect KTE researcher participation by highlighting the role of guanxi as a cultural factor.

Keywords: Guanxi, knowledge transfer exchange, universities, China.

RESUMEN

Este trabajo investiga la relevancia del guanxi (关系) como un factor cultural en la transferencia de conocimiento (KTE), a nivel individual, en el contexto chino de las relaciones universidad-empresa. Adoptando un enfoque cualitativo de estudio de casos, con datos de 50 entrevistas, este trabajo aporta una nueva visión del papel de las redes sociales como valor cultural en la participación de los investigadores universitarios en las actividades de transferencia de conocimiento. Además, este artículo rompe con la tradicional visión lineal hacia el guanxi. En cambio, adopta una perspectiva dinámica, dialéctica y holística hacia el papel del guanxi en los procesos de transferencia de conocimiento en el contexto de las universidades chinas. Se ha encontrado que durante el proceso de transferencia de conocimiento, las redes guanxi deben ser balanceadas con la infraestructura apropiada, personal cualificado e inversión financiera para obtener resultados exitosos. Este estudio enriquece la literatura existente sobre los determinantes que afectan a la participación de los investigadores en proceso de transferencia de conocimiento, destacando el papel del guanxi como un factor cultural.

Palabras clave: Guanxi, transferencia de conocimiento, universidades, China

1. Introduction

Knowledge transfer exchange (KTE) between university and industry is considered an inevitable choice for business success in a rapidly changing environment (Audretsch, Lehmann, & Wright, 2014; Buckley, Clegg, & Tan, 2006). Firms can improve and innovate by obtaining competitive advantages in the market through their participation in KTE (Bruneel, D'Este, & Salter, 2010; Chen, 1994; Huang, Davison, & Gu, 2011). Given its “third mission” that encompasses all universities' activities related to the generation, use, application, and exploitation of knowledge and other capabilities with the non-academic environments (Molas-Gallart & Sinclair, 1999; Piirainen, Andersen, & Andersen, 2016), the universities have undertaken a significant role in knowledge output in the modern economy (Wang, Huang, Chen, Pan, & Chen, 2013). However, university-industry collaboration has been qualified as not being effective enough (Yuan, 2009), and there is an increasing interest in investigating the determinants of university-industry KTE in many countries (Liu & Jiang, 2001; Ramasamy, Goh, & Yeung, 2006; Wang et al., 2013). Thus, university-industry collaboration is an important mechanism for generating knowledge spillovers (Acs, Braunerhjelm, Audretsch, & Carlsson, 2009). Some scholars have investigated the determinants of effective university-industry KTE from different perspectives at an individual level. For example, Link, Siegel, and Bozeman (2007) investigated the determinants of informal KTE, finding that tenured and research-grant active faculty members were more likely to participate in the informal KTE activities. Additionally, Padilla-Meléndez and Garrido-Moreno (2012) studied the motivation of researchers' participation in KTE from an academic perspective. They found personal and professional profiles, institutional factors, social networks, and recognition as factors affecting researcher participation in KTE activities. Furthermore, Tung (1994) commented that cultural values have a direct impact on KTE process. In fact, many studies have demonstrated the benefits of handling cultural factors in inter-organisational relationships (e.g., Davies, Leung, Luk, & Wong, 1995; Luo & Chen, 1997; Yeung & Tung, 1996). However, the importance of cultural factors has not been fully examined (Buckley et al., 2006), and amongst the factors that have been investigated, researchers highly recognised one important cultural value in KTE activities, such as social networks (e.g., Hong, Heikkinen, & Blomqvist, 2010; Padilla-Meléndez & Garrido-Moreno, 2012). Networks provide the opportunity to create social capital and have a positive impact on university-industry links (Link et al., 2007).

Although these studies have shown that social networks have a significant role in university-KTE, the factors studied by Western scholars may not be sufficiently appropriate in the context of China (Ramasamy et al., 2006). Guanxi, a Chinese term, refers to interpersonal connections, permeating every corner of Chinese society (Park & Luo, 2001; Zhang & Zhang, 2006). The guanxi literature has been widely developed in the past three decades and considerable research has demonstrated that guanxi has strong implications for interpersonal and inter-organisational dynamics (e.g., Buckley et al., 2006; Chen & Peng, 2008; Leung, Chan, Lai, & Ngai, 2011; Luo, Huang, & Wang, 2012). Some scholars have studied the role of guanxi in KTE (e.g., Buckley et al., 2006; Hong et al., 2010; Ramasamy et al., 2006) in the context of multinational companies. However, guanxi as a significant cultural value and the importance of social capital have not yet been discussed in the context of researchers' participation in university-industry KTE. The impact of guanxi in the KTE process cannot be ignored (Ramasamy et al., 2006).

The purpose of this paper is to explore the relevance of guanxi as an inseparable Chinese cultural factor (Gao, Ballantyne, & Knight, 2010) affecting researcher participation in KTE in the Chinese university context. Thus, it addresses the individual level of university-industry KTE. This study contributes to the literature in the following aspects. First, unlike the traditional linear perspective towards the role of guanxi in a business context, this study proposes a dynamic, dialectical, and holistic perspective toward the role of guanxi in knowledge transfer. Second, this study makes a contribution to theory in terms of the antecedents of the researchers' attention to sharing knowledge in Chinese universities. Guanxi and trust are identified as potential sources of influence on researchers' intention to participate in KTE, adding to previous research (Huang, Davison, & Gu, 2008).

Next, a brief summary of the theoretical framework of the factors affecting the researchers' motivations to participate in university-industry KTE collaboration, from an individual perspective, their relations with guanxi, and some propositions are included. The research method, results, and discussion follow. The conclusion closes the paper.

2. Theoretical Framework and Propositions

2.1 Motivation of Researchers' Participation in KTE

KTE has been defined as an interactive process that involves the interchange of knowledge between knowledge users and knowledge producers (Mitton, Adair, McKenzie, Patten, & Perry, 2007), requiring interaction among researchers, decision makers, and other stakeholders. KTE occurs through interactions between knowledge inventors and knowledge users, while the process connects people and makes them link together, aiming to obtain bilateral benefits for both parties (Decter, Bennett, & Leseure, 2007). Close connections cultivate personal connections and improve mutual personal trust. There are different forms of KTE between university research centres and companies, including financing research projects, spin-offs, and publications (Liu & Jiang, 2001).

Previous studies have investigated how to generate a successful university industry KTE (e.g., Landry, Amara, & Ouimet, 2007; Zhou & Zhu, 2008). Regarding the previous literature on this topic, the main factors could be grouped together into four main categories, defined as the nature of knowledge, personal and professional profile, recognition, and social networks.

Knowledge can be classified as explicit knowledge or tacit knowledge (De Long & Fahey, 2000; Nonaka, 1994). Explicit knowledge can be codified and embedded in formal rules, tools, and processes, which can be easily documented and shared through electronic or other media. Tacit knowledge is knowledge residing in humans, which cannot be easily explained such as beliefs, intuition, and values (Ramasamy et al., 2006). Knowledge of a tacit nature is more important in making the KTE work efficiently (Buckley et al., 2006), but it cannot be easily articulated or formalised, as it is difficult to specify into texts, drawings, or other symbolic forms.

Regarding the personal and professional profile, researchers in certain research fields are more active in KTE than others (Landry et al., 2007), and institutes of engineering, natural sciences, economics, and management are strongly represented among university-industry KTE research (Arvanitis, Kubli, & Woerter, 2008; Landry et al., 2007). In addition, the mission of higher education institutions also has an influence on KTE. In this vein, Arvanitis et al. (2008) stated that scientific institutes with a stronger orientation to applied research lower the teaching obligations, which supports researchers to have a stronger inclination towards their involvement in the overall KTE activities.

Concerning recognition and non-financial rewards, individual characteristics have a stronger impact on university-industry KTE activities than the characteristics of their departments or universities (D'Este & Patel, 2007). The monetary rewards are not always the best way to motivate researchers. Instead, researchers appreciate many intangible factors including community cooperation, learning new ideas, entertainment, and a better reputation. In the context of China, researchers perceive recognition and non-financial rewards as a significant factor. A recognised researcher would normally get intangible benefits such as a promotion and more opportunities for grants and further research funding (Liu & Jiang, 2001).

Finally, social networks are considered to be one of the most important elements of researchers' participation in KTE activities (Link et al., 2007; Padilla-Meléndez, Del Aguila-Obra, & Lockett, 2013; Padilla-Meléndez & Garrido-Moreno, 2012). KTE benefits both sides; academics increase their research output and business managers advance their technology and innovation capabilities. At times, KTE can be a high-risk investment since there is no guarantee that a technology development project will result in a successful product launch or that the investment will generate a sufficient return (Liu & Jiang, 2001). Social contacts catalyse the occurrence of KTE between inventors and contacts in the business community (Harmon et al., 1997). Informal contacts are often found to be a common form of interaction between universities and industry (Bekkers & Bodas Freitas, 2008), which causes an informal information exchange to be utilised as one of the most efficient ways of exchanging knowledge. Frequent interactions eliminate information asymmetry and facilitate the utilisation of the opportunities provided by research (Landry et al., 2007). Mutual informal reciprocity and exchange, which have dominated university-industry exchanges in the post-war era, were considered an important part of supporting and building university-industry collaboration. In fact, the prior experience of collaborative research lowers related barriers, and the greater levels of trust reduce barriers to university-industry KTE activities (Bruneel et al., 2010).

2.2 Guanxi and its Components

Guanxi first appeared in popular business writing in the 1980s as one significant cultural value affecting doing business in China (e.g., Chen, Chen, & Huang, 2013; Chen & Peng, 2008; Fan, 2002; Leung et al., 2011; Luo et al., 2012). The two Chinese characters,guan (关) xi (系) separately mean “a gate, hurdle or a tie” and “to connect.” Guanxi means to pass the gate to get connections (Lee & Dawes, 2005). The concept of guanxi originated from traditional Chinese philosophy that stresses the importance of an individual's place in the hierarchy of social relationships (Dunning & Kim, 2007; Hwang, 1987; Yeung & Tung, 1996). There is a Chinese saying, “Fei Shui Bu Liu Wai Ren Tian (肥水不流外人田),” which literally means that rich water should be kept in one's own field, reflecting the importance of guanxi in Chinese daily life (Davies et al., 1995; Wong, 2007). Thus, Chinese people used to utilise a different standard to treat people depending on the hierarchy of guanxi (Huang et al., 2011; Lu, 2012).

Two important components of guanxi are renqing and mianzi. Guanxi requires a reciprocal relationship with the implication of an exchange of favours (Pye, 1992). This is related to renqing, which is the mere exchange of favours, sympathy, and help (Khan, Zolkiewski, & Murphy, 2016; Luo & Chen, 1997; Yi & Ellis, 2000). Renqing is an unpaid favour that obligates the other party to pay back the renqing sender in order to maintain harmony in the guanxi balance. Chinese people usually utilise ganqing (感, emotional attachment) to define the quality of a guanxi relationship between two parties. Ganqing is generated from the social interactions of exchanges that lead to a trustworthy relation and co-operation (Berger & Herstein, 2015). Good ganqing improves the positive role of guanxi in social communication. Besides, mianzi is translated, literally, as “face” in English. It is an important cultural value in Chinese culture, defined as the recognition by others of an individual's social standing and position through personal quality, non-personal wealth, authority, and guanxi networks (Ho, 1976; Hwang, 1987, Lockett, 1988). Mianzi is a key component in the dynamics of guanxi (Luk et al., 1999). It is crucial for a Chinese person to have mianzi and do “face work” in front of others within the guanxi circles.

In Chinese societies, the willingness to participate in KTE is perhaps more important than the ability to do so (Ramasamy et al., 2006). The relationship between knowledge sender and knowledge receiver serves as a conduit for knowledge (Jiang, 2005). Kogut and Zander (1992) commented that knowledge transfer is predominantly a social process. Formal institutional support is generally not comprehensive and perfect in an emerging economy like China (Jiang, 2005). Therefore, informal contacts are often found to be a common form of interaction between universities and industries (Bekkers & Bodas Freitas, 2008). Chinese people are used to dealing with their “old” friends who are in their guanxi circle in order to feel safe in situations, which eases the communication. Nonaka (1994) argued that successful knowledge exchange depends to some degree on the ease of communication and on the intimacy of the overall relationships between knowledge sender and knowledge receiver. Furthermore, frequent interactions eliminate information asymmetry and facilitate the utilisation of opportunities provided by research (Landry et al., 2007). Thus, this can be proposed:

Proposition one: Guanxi positively encourages an easy communicational atmosphere for knowledge sender and knowledge receiver during the KTE process.

A substantial body of direct empirical evidence related to the guanxi-KTE link is absent, and mainly concentrates on the inter-firm context. Relationships become crucial in cultivating business relationships (Ramasamy et al., 2006). Jiang (2005) explored the effects of Chinese entrepreneurs' social capital on the success of knowledge transfer by the mediating roles of guanxi development and absorptive capacity. This research confirmed the importance of entrepreneurs' guanxi networks in assessing the needed intellectual capital and gathering information on government policy, and suggested an increase in knowledge transfer by utilising the external relationships. Subsequently, Buckley, Clegg, and Tan (2006) examined the role of guanxi and “face” in knowledge transfer amongst multinational enterprises that had been operating in China for a period of time. They suggested that foreign investors in China must cultivate good connections with local partners and government. During the process, trust amongst employees, local partners, and government officials is built, which lies at the heart of interactions. Furthermore, Huang, Davison, and Gu (2011) investigated the impact of trust, guanxi orientation, and “face”, on the intention of Chinese employees and managers participating in knowledge transfer. They introduced guanxi orientation and “face” as two important factors in knowledge-sharing for maintaining a harmonious working environment, which makes employees feel comfortable to communicate with each other freely, and thereby encourages them to share their knowledge. Finally, Ramasamy, Goh, and Yeung (2006) considered guanxi as enabling transactions, and operationalised it as trust, a relationship commitment, and communication. Their results show that trust and communication are the two main channels of knowledge transfer. However, the two elements both have a negative moderating effect on the opposite channel of knowledge transfer. Thus, these propositions can be proposed:

Proposition two: Guanxi positively improves interpersonal trust-building in the knowledge transfer and exchange.

Proposition three: Guanxi could positively stimulate knowledge transfer or negatively prevent knowledge transfer in a particular context at a particular time.

Trust has a significant role in Chinese society and, as mentioned, is one of the key foundations for building guanxi (Ko & Liu, 2016). It is the core of all relationships (Miesing, Kriger, & Slough, 2007; Morgan & Hunt, 1994) and is associated with security, discretion, and the absence of danger and risk (Marková & Gillespie, 2008). Chinese people prefer dealing with their “old” friends where there is already trust to prevent losses because the trust level of individuals outside their guanxi circle is unknown and uncertain (Leung et al., 2011). A Chinese term that approximates the meaning of trust is xinyong (信用) (Leung et al., 2011; Wang & Hu, 2010). Trust aslo can be translated as xinren (信任) in Chinese. As one popular Chinese saying puts it, “Ren Wu Xin Bu Li (人无信不立),” literally meaning that without credibility, no one can get himself established. The embedded meaning of xinyong is that one's own verbal promise must be honoured when they interact with others to earn personal social credit (Leung et al., 2011). In this vein, Roberts (2000) stated that the exchange of knowledge, particularly tacit knowledge, is not amenable to enforcement by contract but trust. A number of researchers (e.g., Buckley et al., 2006; Liu & Jiang, 2001) confirmed the role of trust in stimulating knowledge-sharing such as leading to knowledge exchange, increasing the willingness to share tacit knowledge, and facilitating knowledge sharing between two persons. Thus:

Proposition four: Personal trust is positively related to knowledge transfer and exchange in the Chinese university context.

3. Research Methodology

We adopt a qualitative case-study approach, with research questions concentrated on “how” and “why” of Chinese university-researcher participation in KTE. This approach is considered as appropriate to generate new theoretical concepts in under-explored areas (Ackroyd & Hughes, 1981). Based on the previous literature on determinants of knowledge transfer, open-ended interview questions were proposed, comprising different aspects related to their motives for the establishment of KTE, and the role of guanxi and its components (trust, communication) in knowledge transfer. The original version of the questionnaire was in English. Considering the language barrier, the English version of the questionnaire was carefully translated into Chinese. We also asked a local professor in a language department to review the Chinese version to ensure validity in a cross-cultural setting (Park & Luo, 2001). After that, in order to improve the accuracy of our questionnaire, we sent the Chinese version to one of the English professors, asking her to translate the Chinese into English. Then, we made a comparison between the one we translated and the one translated by the English professor. Following this process, we finalised the questionnaire.

Regarding context, compared with big cities in China, small and medium sized cities present more emphasis on KTE activities for their local economic development. This research selected one of these small and medium cities, Xingtai, as the research target city. Xingtai University, situated in downtown Xingtai, is a poly-subject local university founded in 1910. This university has 1243 employees, being 916 faculty members, including 360 professors. At present, there are 18 centres, covering literature, science, engineering, history, law, management, history, education, and art. There are 17,000 students on campus. Until 2016, based on the characteristics of study areas, Xingtai University established 26 research centres in order to meet the social needs.

Data was collected through face-to-face interviews. Initially, a mail survey was considered, but as Siu and Kirby (1995) commented, the mail response rate has been proven to be very low in China. We chose personal interviews as our research data channel in order to get more valuable data. We first sent our semi-structured questionnaire with a letter explaining the aim of our research to our intermediary in order to arrange the interviews. Before the face-to-face interview, the questionnaire was first sent to each centre. Fifteen research managers out of the 26 contacted were willing to participate in the study. These 15 managers were in charge of different research centres including engineering, natural sciences, economics, and management. During the interview with the research centre managers, they introduced us to the researchers who are participating in knowledge transfer in their centres. Finally, 50 interviews were established, including 15 with KTE managers and 35 with researchers who participate in KTE activities. The age of interviewees ranges from 35 to 50 years old.

4. Results

Xingtai University has devoted considerable effort to constructing suitable circumstances to promote researchers participating in KTE. Twenty-six knowledge centres have been established in the last 10 years related to all disciplines of the university. As one interviewee (researcher) stated:

The relationship between our classroom and the daily life has become closer than before. Currently, university staffs have designed several new practical courses aimed to connect the traditional classroom to the real society's problem. There is a sound effect. By integrating with the society, the classroom becomes more active. We need more programmes like this.

All university researchers showed great interest in realising their personal value in the academic world by doing successful KTE research. Devoting their entire life to academic teaching, our interviewees were highly fulfilled in academics. High recognition brings additional funding mechanisms to further their research agenda or personal life.

4.1 Guanxi and KTE

Guanxi networks appear to be a major source of knowledge that researchers utilise to participate in KTE activities. As mentioned, all of the universities rely on their guanxi networks for potential future KTE partners. One researcher commented on her experience on doing KTE with a Beijing-based company. At the very beginning, our interviewee attempted to seek one company to establish one of her experiments for quite a long time. Because of the special characteristics of the chemical experiment (new technology to extract one chemical substance from other chemical substance), it was quite difficult to find a business partner. Finally, by going to a social event, our interviewee became acquainted with one company's manager. After long-term interaction, they developed good guanxi between them. This company's manager told the story of her company. Our interviewee realised that what the company manager was looking for was exactly what the researcher needed. Consequently, the long-term interaction promoted the generation of good guanxi. This is an example of good guanxi as a bridge to connect both parties for further cooperation. She stated that “without guanxi, sometimes things cannot be developed, and the sentence Yi Fan Feng Shun (一帆风顺) applies.” In the Chinese language, Yi Fan Feng Shun is used to describe how to have a favourable situation to make everything goes smoothly.

One researcher did not develop her guanxi networks at the very beginning. Chinese people usually “Zou Yi Quan” (走一圈 walk around) at the Chinese new year. Zou Yi Quan literally means, “to do gift giving amongst all acquaintances in the guanxi circle.” In this way, people try to maintain or get a good guanxi relationship with their current or future partners. However, she did not do so at that time. When she needed help from her guanxi circle, she was not in a favourable situation. She was trying to apply to obtain a certificate. Normally, people in the guanxi circle can obtain it within 15 days. In her case, she had spent more than nine months and was still waiting when we interviewed her.

All interviewees commented that guanxi networking took place in many different ways, ranging from formal guanxi networking events to meeting people informally. For example, one researcher stated: “Classmate parties or social parties work very well in developing guanxi and obtaining effective knowledge.” The majority of interviewees (90%) stated that they already had KTE activities with those with whom they had guanxi networks. These networks had been formed over a period of years through previously working in industry, attending academic/government/province meetings, even someone's wedding, and maintaining a link with former classmates from high school, primary school, university, or some training courses. One researcher commented:

I worked in one public company for many years. This company belongs to China Central Television. My job was to provide services or solutions to other companies. Because of the nature of my job, I knew lots of business friends and got quite good guanxi with them. Nowadays, many parties are held to renew our friendships. Through these parties, I have more chance to get more knowledge and more opportunity to develop KTE activities.

Nearly all interviewees (84%) though that guanxi could facilitate mutual communication. Some interviewees thought that guanxi sometimes prevented deep communication. These researchers evaluated more the technical ability of their guanxi partners in KTE. They prefer to use a strategic communication method to protect their guanxi partners' “face”. Ineffective communication leads to a knowledge asymmetry between knowledge provider and knowledge receiver. As one interviewee stated “knowledge provider liaised frequently with knowledge receiver because of the good guanxi during the KTE activities to reduce the knowledge asymmetry and to increase the ability of absorbing knowledge.” Good guanxi could be deemed as a broker between knowledge provider and knowledge receiver. It improves “deep” communication between both sides. One interviewee commented:

Classmate meeting was extremely cordial. We bring up directly a matter. We had already known each very well. We have no fear to talk. Doing KTE between friends, we have easy and right manner to communicate with each other. The communication is deep and effective even sometimes maybe we can argue with each other. Because of the long-term relation, we trust each other. Sometimes when we do KTE research with unknown people, the communication is not quite direct and effective.

The majority of interviewees (72%) thought that previous relationships, guanxi, positively cultivate trust-building during the KTE activities. Trust is deemed as fundamental for doing KTE research. “Doing some KTE activities are quite risky and costly, it is like burning your money. Without mutual trust, KTE activities cannot be established.” “Although some researchers are in some research program, they are not concentrating on the research investigation. Instead, they are focusing on things which are not related to their research.” In some sense, guanxi networks, as positive for trust, encourages the cooperation between knowledge provider and knowledge receiver. One interviewee stated:

If you do not have trust, the KTE activities cannot go far. For me doing business (KTE research) with an unknown person is near impossible. Developing KTE with these acquaintances makes me feel comfortable. Previous interactions give me more trust on the guy whom is going to cooperate with.

Although the majority of interviewees (72%) confirmed the important role of guanxi in building trust, some researchers (28%) showed anxiety about guanxi in building trust. These researchers argued that guanxi networks sometimes could be manipulated by their guanxi partner as an instrument for maximising their personal benefit. In the guanxi circle, both sides have more understanding of each other. The long-term guanxi logically produces personal trust. Normally, acquaintances can obtain better their objectives, as they have more mutual personal trust, and this enhances their collaboration. The social activities mainly occurred in a guanxi circle. However, with the development of a market economy, the economic rationality erodes the concept of guanxi between acquaintances. Some people take advantage of their acquaintances fraudulently for their personal interest.

5. Discussion

The role of the Chinese university has been changing since the Opening and Reform Policy that was initiated in 1978, aiming to reform China from a planned economic system to a market-oriented economic system. Since then, Chinese universities have begun to shift from training human resources and conducting research, towards emphasising the outcome of research, which provides more direct technological support for industrial technological progress (e.g. Liu & Jiang, 2001; Wang et al., 2013). Universities have been placed at the core for the development of technological capabilities.

With the need for continuous technological development to gain competitive advantage in today's international market, firms are looking for external favours to help them speed up the innovation process. One of the most attractive resources is the university (Lee & Win, 2004). Despite considerable research on KTE, little research has been conducted on the cultural factors affecting the participation of researchers in KTE actions (Padilla-Meléndez & Garrido-Moreno, 2012). We conducted this research in order to study the motivation of researchers in participating in KTE activities by emphasising the relevance of guanxi and its components in university-industry KTE in China from the perspective of university researchers (individual level), and we analysed several cases in one Chinese university context, gaining insight into our theoretically-grounded propositions.

Regarding proposition 1, generating guanxi comes from the social activities in terms of gift-giving (Zhou & Guang, 2007). For example, interviewee 6 commented how she forgot to “walk round” (giving gifts). On the renqing balance, there is no liability to be paid, thus, owing to the characteristic of reciprocity, there is no obligation to pay back a renqing to other agents from her counterpart. Guanxi is not created by this researcher and her counterparts because of a lack of a sense of obligation and indebtedness among partners (Luo & Chen, 1997; Shi et al., 2011). Hence, there was a short-cut stimulated by guanxi, and our interviewee 6 suffered a serious loss in terms of time. Shaalan et al. (2013) commented that the mutual social networks improve the mutual effective communication. Owing to the guanxi relations, the interviewees feel comfortable and free to talk about the knowledge about future/current knowledge transfer research in their guanxi circle. Access to information is considered more as a privilege than a necessity. “Who you know” has more weight than “what you know.” Researchers obtain more opportunities to do KTE research through their guanxi circle.

Concerning proposition 2 and 3, guanxi sometimes is treated as a shield for building trust. Some interviewees refused to cooperate with those with whom they do not have guanxi. One who is in the guanxi circle is deemed as having a high trust level (Leung et al., 2011). The results reflect what Liu and Jiang (2001) explained—that KTE per se is a high-risk process. There is no guarantee that a technology or knowledge development will result in a successful product launch or that an investment will generate a sufficient return. People are afraid of cooperation with the unknown. Trust as the core of all relationship changes (Morgan & Hunt, 1994) gives people the sense of security, discretion, and the absence of danger and risk (Marková & Gillespie, 2008). Thus, researchers prefer to do transactions with their “old” friends. People help those who are in the guanxi circle, and sometimes not only have a desire for sufficient return, but also want to be recognised by others for his/her individual social standing and position. That is what we call mianzi (face) in Chinese. It is crucial for a Chinese person to do “face” work in front of others within the guanxi networks (Luk et al., 1999) to obtain more access to valuable resources. “Face” work has to go hand-in-hand with nurturing guanxi. It provides leverage during interpersonal exchanges of favours; for example, mealtimes increase the level of trust. The increased level of trust in turn enhances the quality of guanxi and protects their counterpart's “face”. In this sense, 28% of researchers use the strategic communication method with their counterpart to prevent their counterpart's “face” within their guanxi networks.

However, not all the researchers confirmed the role of trust derived from a previous guanxi relationship. Chinese culture has been undergoing many changes in several aspects (Faure & Fang, 2008). As some researchers stated, “Nowadays, with the high development of market economy, the economic rationality erodes the meaning of guanxi.” High rapid economic development drives people to be more selfish and more individualistic. A new phrase arises to describe this phenomenon: Sha Shu (杀熟). Sha Shu means people only take advantage of their guanxi circle by making money fraudulently. The object of deception is the one who has already built trust. Some researchers worry about the trust that is built by guanxi. They show more interest in doing KTE activities with whom they have strong financial and infrastructural support. Undoubtedly, researchers confirmed the significance of guanxi in imitating the conversation between interviewees and their counterparts at a particular time, context, and situation. Guanxi networks help to build trust, protect “face,” and thus facilitate the KTE process. However, the influence of guanxi in KTE research is not linear. Depending on the situation, time, and context, it could be positive, negative, or neutral. People in the guanxi circle, in order to save their counterpart's “face” and to avoid making the counterparts lose “face” in their guanxi circle, and because of the insufficient ability or insufficient benefit in doing knowledge transfer, adopt a tactful communication method to escape the possibility of doing knowledge transfer. Moreover, interviewees considered that good guanxi sometimes could be manipulated by their counterparts in the guanxi circle, which gives rise to losses in their KTE activities.

6. Conclusion

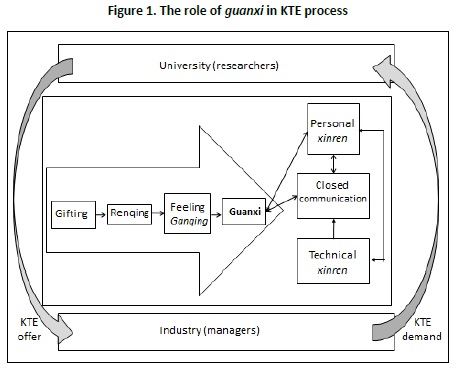

This paper explores the relevance of guanxi in affecting researchers' participation in KTE in the Chinese university context. The contribution of this work is to provide a dialectical, dynamic, and holistic perspective toward guanxi in KTE. The role of guanxi could be positive or negative depending on the context, situation, and time (dialectic perspective). Good guanxi can positively encourage the mutual parties involved in the KTE research and also negatively prevents deeper communication because of “face” work. Depending on the different contexts, situations, and time, the role of guanxi on KTE shifts from one to another (dynamic perspective). The role of guanxi should be seen also from a holistic perspective that considers the situation, time, and context. Long-term gift-exchanging encourages renqing, and furthermore builds mutual emotional sentiment (ganqing) between both sides (see Figure 1). With reciprocal favour exchange, mutual sides construct good guanxi. In particular, guanxi is positive in activating effective communication, encouraging mutual personal trust (xinyong), and establishing a short-cut for researchers and knowledge receivers. Furthermore, if both parts have not done the “face” work previously, KTE is not the mutual willingness, and this affects negatively reaching the agreement on KTE activities. However, evidence does not provide strong support for stating that mutual guanxi networks can guarantee the establishment of KTE activities because of the changing Chinese cultural values.

In other words, the mixed results of guanxi on business performance seem to be far from reality. The changing role of guanxi in dynamic circumstances invokes a heated debate. Unlike the previous linear perspective towards guanxi, this study argues that the role of guanxi varies depending on the context, time, and situation. In a certain situation, context, and time, guanxi is valid to explain researcher participation in KTE activities, proving their significance in deep communication, personal trust, and priority of access to knowledge. However, good guanxi could result in bad performance of the KTE. Guanxi and personal trust are all identified as potential sources of influence on researchers' intentions to participate in KTE. However, guanxi is not the panacea to start a KTE. In order to establish an effective transfer of knowledge, a harmonious environment is needed where the role of guanxi and personal trust should be balanced with technical ability, including an appropriate research infrastructure, qualified staff, and financial investment.

As recommendations for institutions, given the significance of social networks, universities should encourage their KTE staff to participate in more academic training courses, academic exchange programmes, informal opportunities for meeting and networking with knowledge providers or knowledge users, and to establish wider guanxi networks. Additionally, universities should improve their ability to stimulate KTE activities from not only the researchers' perspective, but also provide the basic infrastructure for research.

As limitations, firstly, this is an exploratory study with limited results; it is a first attempt to provide a research framework from the current literature to present some empirical evidence for further development. Secondly, although the questionnaire has been translated carefully into the Chinese language, owing to the language itself, special characteristics of some terms could not be translated.

In this study, we investigated the paradoxical and contradictory effects of guanxi in knowledge transfer. Future research could adopt this dynamic perspective and investigate how to balance the role of guanxi and personal trust with technical trust. The role of guanxi is like a double-edged sword that could bring both positive and negative outcomes to knowledge transfer research. Future research should provide evidence about which conditions decide the changeable effect from positive to negative or from negative to positive. Moreover, this study is established from the university researchers' perspective, a knowledge-sender perspective, and future study could investigate the role of guanxi from a knowledge-receiver perspective or from both the knowledge-sender and knowledge-receiver perspective.

REFERENCES

Ackroyd, S., & Hughes, J. A. (1981). Data collection in context. New York: Longman. [ Links ]

Acs, Z. J., Braunerhjelm, P., Audretsch, D. B., & Carlsson, B. (2009). The Knowledge Spillover Theory of Entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 32(1), 15-30. [ Links ]

Arvanitis, S., Kubli, U., & Woerter, M. (2008). University-industry knowledge and technology transfer in Switzerland: What university scientists think about co-operation with private enterprises. Research Policy, 37(10), 1865–1883. [ Links ]

Audretsch, D. B., Lehmann, E. E., & Wright, M. (2014). Technology transfer in a global economy. Journal of Technology Transfer, 39(3), 301–312. [ Links ]

Bekkers, R., & Bodas Freitas, I. M. (2008). Analysing knowledge transfer channels between universities and industry: To what degree do sectors also matter? Research Policy, 37(10), 1837–1853. [ Links ]

Berger, R., & Herstein, R. (2015). Strategies for marketing diamonds in China from the perspective of international diamond SMEs compared to the west. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 22(3), 549–562. [ Links ]

Bruneel, J., D'Este, P., & Salter, A. (2010). Investigating the factors that diminish the barriers to university-industry collaboration. Research Policy, 39(7), 858–868. [ Links ]

Buckley, P. J., Clegg, J., & Tan, H. (2006). Cultural awareness in knowledge transfer to China-The role of guanxi and mianzi. Journal of World Business, 41(3), 275–288. [ Links ]

Chen, C. C., Chen, X.-P., & Huang, S. (2013). Chinese Guanxi : An Integrative Review and New Directions for Future Research. 中国人的关系: 综合文献回顾及未来研究方向. Management and Organization Review, 9(1), 167–207. [ Links ]

Chen, E. Y. (1994). The evolution of university-industry technology transfer in Hong Kong. Technovation, 14(7), 449–459. [ Links ]

Chen, X. P., & Peng, S. (2008). Guanxi dynamics: Shifts in the closeness of ties between Chinese coworkers. Management and Organization Review, 4(1), 63–80. [ Links ]

D'Este, P., & Patel, P. (2007). University-industry linkages in the UK: What are the factors underlying the variety of interactions with industry? Research Policy, 36(9), 1295–1313. [ Links ]

Davies, H., Leung, T. K. ., Luk, S. T. ., & Wong, Y. (1995). The benefits of “Guanxi”: The value of relationships in developing the Chinese market. Industrial Marketing Management, 24(3), 207–214. [ Links ]

De Long, D. W., & Fahey, L. (2000). Diagnosing cultural barriers to knowledge management. Academy of Management Perspectives, 14(4), 113–127. [ Links ]

Decter, M., Bennett, D., & Leseure, M. (2007). University to business technology transfer-UK and USA comparisons. Technovation, 27(3), 145–155. [ Links ]

Dunning, J. H., & Kim, C. (2007). The Cultural Roots of Guanxi: An Exploratory Study. World Economy, 30(2), 329–341. [ Links ]

Fan, Y. (2002). Questioning guanxi: Definition, classification and implications. International Business Review, 11(5), 543–561. [ Links ]

Faure, G. O., & Fang, T. (2008). Changing Chinese values: Keeping up with paradoxes. International Business Review, 17(2), 194–207. [ Links ]

Gao, H., Ballantyne, D., & Knight, J. G. (2010). Paradoxes and guanxi dilemmas in emerging Chinese-Western intercultural relationships. Industrial Marketing Management, 39(2), 264–272. [ Links ]

Harmon, B., Ardishvili, A., Cardozo, R. N., Elder, T., Leuthold, J., Parshall, J., … Smith, D. (1997). Mapping the university technology transfer process. Journal of Business Venturing, 12(6), 423–434. [ Links ]

Ho, D. Y. (1976). On the Concept of Face. American Journal of Sociology, 81(4), 867–884. [ Links ]

Hong, J., Heikkinen, J., & Blomqvist, K. (2010). Culture and knowledge co-creation in R&D collaboration between MNCs and Chinese Universities. Knowlege and Process Management, 17(2), 62–73. [ Links ]

Huang, Q., Davison, R. M., & Gu, J. (2008). Impact of personal and cultural factors on knowledge sharing in China. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 25(3), 451–471. [ Links ]

Huang, Q., Davison, R. M., & Gu, J. (2011). The impact of trust, guanxi orientation and face on the intention of Chinese employees and managers to engage in peer-to-peer tacit and explicit knowledge sharing. Information Systems Journal, 21(6), 557–577. [ Links ]

Hwang, K. (1987). Face and Favor: The Chinese Power Game. American Journal of Sociology, 92(4), 944–974. [ Links ]

Jiang, C. (2005). The impact of entrepreneur's social capital on knowledge transfer in Chinese high-tech firms: the mediating effects of absorptive capacity and guanxi development. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 5(3/4), 269–283. [ Links ]

Khan, A., Zolkiewski, J., & Murphy, J. (2016). Favour and opportunity: renqing in Chinese business relationships. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 31(2), 183–192. [ Links ]

Ko, W. W., & Liu, G. (2016). A typology of guanxi-based governance mechanisms for knowledge transfer in business networks of Chinese small and medium-sized enterprises. Group & Organization Management, 42(4), 548–590. [ Links ]

Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the Firm, Combinative Capabilities, and the Replication of Technology Author (s): Bruce Kogut and Udo Zander Source: Organization Science, Vol . 3, No . 3, Focused Issue: Management of Technology. Organization Science, 3(3), 383–397.

Landry, R., Amara, N., & Ouimet, M. (2007). Determinants of knowledge transfer: Evidence from Canadian university researchers in natural sciences and engineering. Journal of Technology Transfer, 32(6), 561–592. [ Links ]

Lee, D. Y., & Dawes, P. L. (2005). Guanxi, trust, and long-term orientation in Chinese business markets. Journal of International Marketing, 13(2), 28–56. [ Links ]

Lee, J., & Win, H. N. (2004). Technology transfer between university research centers and industry in Singapore. Technovation, 24(5), 433–442. [ Links ]

Leung, T. K. P., Chan, R. Y. K., Lai, K. H., & Ngai, E. W. T. (2011). An examination of the influence of guanxi and xinyong (utilization of personal trust) on negotiation outcome in China: An old friend approach. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(7), 1193–1205. [ Links ]

Link, A. N., Siegel, D. S., & Bozeman, B. (2007). An empirical analysis of the propensity of academics to engage in informal university technology transfer. Industrial and Corporate Change, 16(4), 641–655. [ Links ]

Liu, H., & Jiang, Y. (2001). Technology transfer from higher education institutions to industry in China: Nature and implications. Technovation, 21(3), 175–188. [ Links ]

Lockett, M. (1988). Culture and the Problems of Chinese Management. Organization Studies, 9(4), 475–496. [ Links ]

Lu, L. (2012). Guanxi and renqing: the roles of two cultural norms in Chinese business. International Journal of Management, 29(2), 466–476. [ Links ]

Luk, S. T. K., Fullgrabe, L., & Li, S. C. Y. (1999). Managing Direct Selling Activities in China. Journal of Business Research, 45(3), 257–266. [ Links ]

Luo, Y., & Chen, M. (1997). Does guanxi influence firm performance? Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 14, 1–16. [ Links ]

Luo, Y., Huang, Y., & Wang, S. L. (2012). Guanxi and organizational performance: A meta-analysis. Management and Organization Review, 8(1), 139–172. [ Links ]

Marková, I., & Gillespie, A. (2008). Trust and distrust: Sociocultural perspectives. USA: Information Age Publishing Inc. [ Links ]

Miesing, P., Kriger, M. P., & Slough, N. (2007). Towards a model of effective knowledge transfer within transnationals: The case of Chinese foreign invested enterprises. Journal of Technology Transfer, 32(1–2), 109–122. [ Links ]

Mitton, C., Adair, C. E., McKenzie, E., Patten, S. B., & Perry, B. W. (2007). Knowledge transfer and exchange: Review and synthesis of the literature. The Milbank Quarterly, 85(4), 729–768. [ Links ]

Molas-Gallart, J., & Sinclair, T. (1999). From technology generation to technology transfer: the concept and reality of the “Dual-Use Technology Centres.” Technovation, 19(11), 661–671. [ Links ]

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relations. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38. [ Links ]

Nonaka, I. (1994). A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation. Organization Science, 5(1), 14–37. [ Links ]

Padilla-Meléndez, A., Del Aguila-Obra, A. R., & Lockett, N. (2013). Shifting sands: Regional perspectives on the role of social capital in supporting open innovation through knowledge transfer and exchange with small and medium-sized enterprises. International Small Business Journal, 31(3), 296–318. [ Links ]

Padilla-Meléndez, A., & Garrido-Moreno, A. (2012). Open innovation in universities: What motivates researchers to engage in knowledge transfer exchange? International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 18(4), 417–439. [ Links ]

Park, S. H., & Luo, Y. (2001). Guanxi and organizational dynamics: Organizational networking in Chinese firms. Strategic Management Journal, 22, 455–477. [ Links ]

Piirainen, K. A., Andersen, A. D., & Andersen, P. D. (2016). Foresight and the third mission of universities: the case for innovation system foresight. Foresight, 18(1), 24–40. [ Links ]

Pye, L. W. (1992). Chinese negotiating style. Commercial Approaches and Cultural Principles. Westport: Quorum Books. [ Links ]

Ramasamy, B., Goh, K. W., & Yeung, M. C. H. (2006). Is Guanxi (relationship) a bridge to knowledge transfer? Journal of Business Research, 59(1), 130–139. [ Links ]

Roberts, J. (2000). From Know-how to Show-how? Questioning the Role of Information and Communication Technologies in Knowledge Transfer. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 12(4), 429–443. [ Links ]

Shaalan, A. S., Reast, J., Johnson, D., & Tourky, M. E. (2013). East meets West: Toward a theoretical model linking guanxi and relationship marketing. Journal of Business Research, 66(12), 2515–2521. [ Links ]

Shi, G., Shi, Y., Chan, A. K. K., Liu, M. T., & Fam, K. S. (2011). The role of renqing in mediating customer relationship investment and relationship commitment in China. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(4), 496–502. [ Links ]

Siu, W.-S., & Kirby, D. A. (1995). Marketing in Chinese small business: Tentative theory. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 3(3), 309–342. [ Links ]

Wang, G., & Hu, B. (2010). The study of the influence of personal relationship on the knowledge transfer: The role of xinyong. Research on Financial and Economic Issues, (3), 103–108. [ Links ]

Wang, Y., Huang, J., Chen, Y., Pan, X., & Chen, J. (2013). Have Chinese universities embraced their third mission ? New insight from a business perspective. Scientometrics, 97(2), 207–222. [ Links ]

Wong, M. (2007). Guanxi and its role in business. Chinese Management Studies, 1(4), 257–276. [ Links ]

Yeung, I. Y. M., & Tung, R. L. (1996). Achieving business success in Confucian societies: The importance of guanxi (connections). Organizational Dynamics, 25(2), 54–65. [ Links ]

Yi, L. M., & Ellis, P. (2000). Insider-outsider perspectives of Guanxi. Business Horizons, 43, 25–30. [ Links ]

Yuan, Y. (2009). Review on knowledge transfer research of university in China. Journal of Modern Information, 11, 221–224. [ Links ]

Zhang, Y., & Zhang, Z. (2006). Guanxi and organizational dynamics in China: A link between individual and organizational levels. Journal of Business Ethics, 67(4), 375–392. [ Links ]

Zhou, F., & Zhu, X. (2008). University technology transfer in China: Do the resources matter? Journal of American Academy of Business, 13(1), 185–190. [ Links ]

Zhuo, C., & Guang, H. (2007). Gift giving culture in China and its cultural values. Intercultural Communication Studies, 16(2), 81–93. [ Links ]

Received: 15 November 2016

Revisions required: 18 May 2017

Accepted: 12 July 2017