Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.14 no.1 Faro mar. 2018

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2018.14101

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Tourism, cultural activities and sustainability in the Spanish Mediterranean regions: a probit approach

Turismo, actividades culturales y sostenibilidad en las regiones del Mediterráneo español: un análisis mediante modelos probit

Andres Artal-Tur*, Antonio Juan Briones-Peñalver**, Marina Villena-Navarro***

*Technical University of Cartagena, Faculty of Business, Dept. of Economics, C\ Real 3, 30201, Cartagena, Spain, Andres.artal@upct.es

**Technical University of Cartagena, Faculty of Business, Dept. of Economics, Spain, aj.briones@upct.es

***Technical University of Cartagena, Faculty of Business, Dept. of Economics, Spain, m.villena@upct.es

ABSTRACT

Culture is the preferred activity of sun & sand tourists visiting the Spanish Mediterranean regions. Improving our knowledge on the factors surrounding this type of demand appears to be pivotal for the continuous renewal of those mature destinations. With this objective we apply probit models to a data set of more than 200,000 questionnaires accounting for the socio-economic characteristics of the tourists, their trip behaviour, and destination and time fixed effects. Results allow us to identify interesting characteristics of tourism and of cultural activities, making this product a good candidate to contribute to the sustainability of destinations.

Keywords: Tourism, cultural activities, sustainability, probit models, tourism policy.

RESUMEN

La cultura es la actividad preferida de los turistas de sol y playa que visitan las regiones del Mediterráneo español. Aumentar el conocimiento de los factores asociados a este tipo de demanda resulta clave para la renovación de estos destinos maduros. Con este objetivo aplicamos modelos probit a una muestra de datos de más de 200,000 cuestionarios, que recogen información sobre las características socio-económicas del turista, su patrón de viaje, y los propios efectos regionales y temporales del análisis. Los resultados de la investigación nos ayudan a identificar características propias del turismo de actividades culturales que lo convierten en un buen candidato para contribuir a mejorar la sostenibilidad de los destinos.

Palabras clave: Turismo, actividades culturales, sostenibilidad, modelos probit, política turística.

1. Introduction

Cultural tourism is becoming a relevant field of study since researchers and policy makers started to recognise the number of connections existing between culture and tourism. Those activities account for 40 per cent of international tourism arrivals, although people travelling for specific cultural motives probably represent just 5-10 per cent of them as pointed by the World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO, 2015). According to Europa Nostra more than 50% of tourist activity in Europe is driven by cultural heritage, and cultural tourism is expected to be one of the most dynamic activities of the tourism sector in the following years (Europa Nostra, 2016). In the case of Spain, tourists travelling for specific cultural motives were in 2014 about 24 million people, 13.7 million of them domestic travellers (14% of domestic leisure travellers), plus 10.3 million of foreign tourists (17% of international leisure arrivals). Both groups of specific cultural travellers reported a revenue of 7,289 and 9,744 million, respectively. Further on, international tourists engaged in cultural activities represented more than 55% of the 65 million of international visitors arriving to the country in 2014 (AEC, 2015).

Culture is in itself a difficult concept to define, in this way the World Tourism Organisation defines cultural tourism as that including “all movements of persons satisfying the human need for diversity, tending to raise the cultural level of the individual and giving rise to new knowledge, experience and encounters”. However, the complexity of the topic is also highlighted by the other definition adopted by this same institution, that states that “cultural tourism includes movements of persons for essentially cultural motivations such as study tours, performing arts and other cultural tours, travel to festivals and other cultural events, visit to sites and monuments, travel to study nature, folklore, art or pilgrimages” (UNWTO, 1985, p.131). As shown, both definitions tend to capture the qualitative and quantitative sides of cultural tourism. May (1996) for example identified motivations of seeking for authenticity among cultural tourists. Learning appears as other important motivation for cultural tourists as well (Richards, 2001). Moreover, cultural tourism has grown and developed into a mass market, comprising a number of traditional and emerging cultural products, as the heritage tourism (Timothy & Boyd, 2003), the gastronomic tourism (Hjalager & Richards, 2002), or events tourism (Richards & Palmer, 2010; Getz, 2008), or even the rising product of dark tourism building on the remembrance of historical events (Stone, 2006).

Museums and monuments have traditionally constituted the core of European cultural tourism. In the past twenty years the need to attract more tourists has led urban centres to develop new cultural attractions, in the fashion of what Ritzer (1999) termed the development of the “new cathedrals of consumption”. Richards (1996) suggested that early approaches to the relationship between tourism and culture tended to be based on the “sites and monuments” approach, where the cultural attractions of a country or region were basically seen as the physical cultural sites that were important for tourism. Gradually, a broader view of culture in tourism emerged, which included the performing arts, crafts, cultural events, architecture and design, and more recently, creative activities and intangible heritage (OECD, 2014). This has also stimulated a move away from product-based to process-based or “way of life” definitions of culture. Tourists increasingly visit destinations to experience the lifestyles, everyday culture and customs of the resident people, with interactions with local culture representing an important trend among the new types of tourism arising nowadays (OECD, 2009).

In this setting, cultural tourism is showing a number of characteristics that makes it a very attractive area of research. It is still an area in development, with cultural tourism capturing the attention of outstanding researchers (McKercher & du Cross, 2002; Richards & Wilson, 2006; Richards, 2011). Culture widely understood is becoming the pivotal asset for the renovation and updating of mature destinations, as well as for the launching of new ones. A good example of this is the salient role that “city tourism” is acquiring in the world tourism market, attracting a big share of new visitors in the EU territory (ETC, 2005). This explains that the European Commission and The Council of Europe have declared “cultural tourism” to be one of the current priorities for tourism sustainability. In their own words, “the competitiveness of the European tourism industry is closely linked to its sustainability, as the quality of tourist destinations is strongly influenced by their natural and cultural environment and their integration into the local community. Europe must offer sustainable and high-quality tourism, playing on its comparative advantages, in particular the diversity of its countryside and extraordinary cultural wealth” (European Commission, 2007).

In this context, the present paper pursues improving the understanding of the context surrounding cultural tourism. In doing so, we focus on the case of the Spanish Mediterranean coast, the main destination at the country level and one of the most visited in Southern Europe. Building on a wide data set we seek for identifying the factors that increase the probability of becoming a visitor pursuing cultural activities, and the main differences between this type of tourists and the general tourists visiting this area. After this introduction, the rest of the paper is organised as follows. In section 2 we present a descriptive analysis of tourists of cultural activities.

Section 3 estimates and discusses the results of probit models explaining the factors surrounding several types of cultural tourists, namely tourists doing cultural visits, those attending to cultural events, and the ones coming in search of other type of cultural activities. Section 4 concludes and provides some guidelines on destination management emerging from the investigation.

2. Cultural tourism in the Spanish Mediterranean region

2.1 The profile of the tourists

We start by reviewing the profile of general tourists in the region, further focusing on the main characteristics of tourists of cultural activities. Our data sample comes from the Tourism Expenditure Survey (EGATUR) of the Spanish Institute of Tourism Studies (IET). After depuration, the sample comprises around 290,000 questionnaires characterising foreign tourists visiting the Spanish Mediterranean coast (including regions (NUTS 2) of Catalonia, Valencia, Murcia, Andalusia and Balearic Islands) during the period 2004-2009. This geographical area is the most important destination in Spain, and one of the leading places in Europe, accounting for more than 65% of international arrivals to the country, what represents around 40 million of tourists per year. The questionnaire developed by IET provides information on socio-demographic profile of visitors (gender, age, studies, income level, etc.), features of the trip (length of stay, accommodation, activities developed during the stay), and the behaviour of tourists regarding some key variables (overall trip satisfaction, expenditure patterns, and stay duration). It also includes a question on the purpose of the visit, either for leisure, business, or studies.

A first look at data in table 1 shows that leisure tourists account for the bulk of the sample, with 80% of the total share, followed by business tourists, 16%, and student ones, 3%. Catalonia is the most visited region in our sample, 36% of visitors, followed by Balearic Islands, 23%, Andalusia, 20%, and Valencia, 16%. Gastronomic activities are followed by 11% of the sample, health by 3%, and gambling by 2%. Along this investigation we will employ a general definition of a cultural tourist as “a visitor that pursues any type of cultural activities on their holiday time”. The survey data we employ provides three main questions regarding the cultural activities developed by visitors. The first one refers to visitors being engaged in cultural visits to museums, exhibitions, etc., the second one includes visitors going to cultural events, while the third one covers other cultural activities developed by visitors. The number of tourists that declare to have participated in cultural visits account for 56% of the sample, cultural events for 11%, and other cultural activities for 9% (table 1). Number of tourists that declare to have made all three cultural activities along their trip account for 4% of the sample, and those pursuing cultural activities plus cultural events represent 10%.

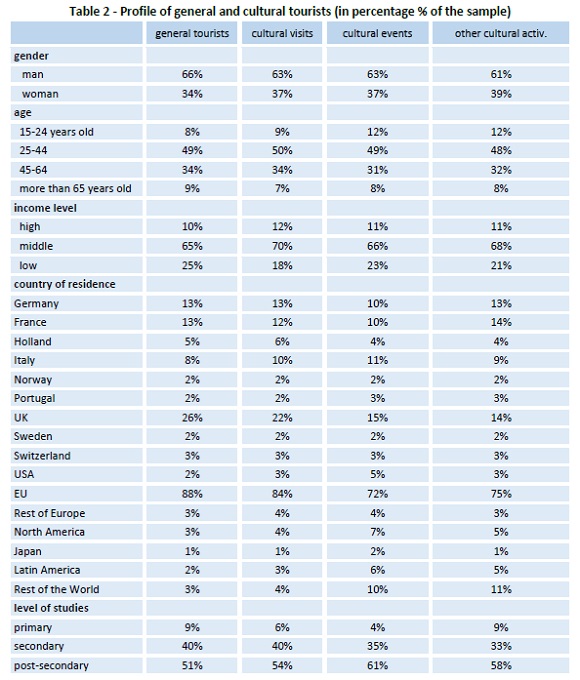

Table 2 shows that the general tourist visiting Spain is majorly a man, aged 25-44 years old, and showing middle-income level (between 25,000-80,000 per year). General tourists come mainly from the EU area, leading the ranking those coming from the UK, France, Germany and Italy. The level of studies is in general post-secondary enrolment, followed by secondary studies. Equally, table 2 shows that tourists engaged in cultural visits (museums, exhibitions) show a very similar profile to the general, full sample, tourists, just with slight differences in number of post-secondary level of studies, non-EU residents, women, and middle-income visitors. For those pursuing cultural events, and other cultural activities additional differences arise for presence of women, younger aged (15-24 years old), lower- income level, coming from the UK, the Americas, and from the Rest of the World, and regarding those tourists with post- secondary education.

Table 3 includes the trip characteristics of tourists in our sample, showing that first visitors are more present in cultural tourism, while general tourists show longer tradition in coming to these destinations, although both collectives use to revisit them for several times. The frequency of the visit ranges between one per quarter and less than one per year. Both groups of tourists mainly employ hotel accommodation, as well as houses of family and relatives (VFR), while second-home accommodation is usually employed by 10% of visitors in all groups. The mean of transport employed to arrive to the destination is mainly the airplane, given that they are international tourists, although some of them employ their own car. The group size is majorly of one or two people, while most visited region in the Spanish seaside is Catalonia for cultural visits, followed by Andalusia for all three cultural reasons, and Valencia for the two later ones. The length of stay for cultural reasons is greater than for general tourist’s trips, mainly for cultural events and other cultural activities.

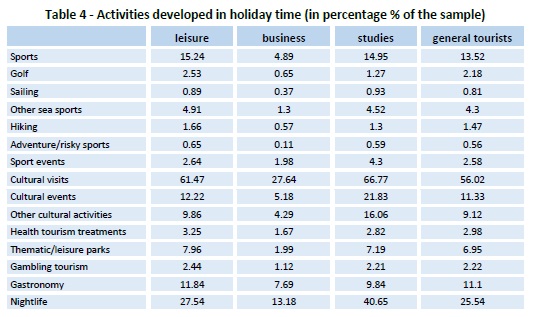

In what refers to the activities developed during the holiday by purpose of the visit, table 4 shows that leisure tourists use to enjoy cultural visits, cultural events, nightlife activities, gastronomy, and sports. Business tourists mainly engage with cultural visits, gastronomy, and nightlife, while studies´ travellers focus on cultural facilities and events, nightlife,gastronomy, and sports. In general, all tourists majorly enjoy from the cultural supply, gastronomy, and nightlife while visiting the Spanish Mediterranean, all these being manifestations of the cultural richness offered by those destinations.

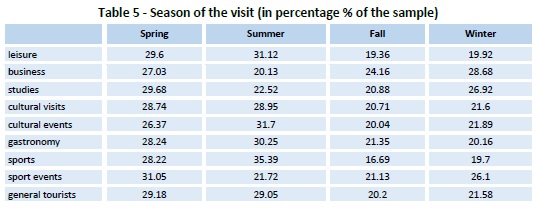

The preferred season of the visit is the summertime for leisure purposes, but in spring and wintertime for business and studies´ trips. Cultural visits and events mainly take place in spring and summertime, as well as gastronomic and sport activities, mostly in line with the general tourists (Table 5).

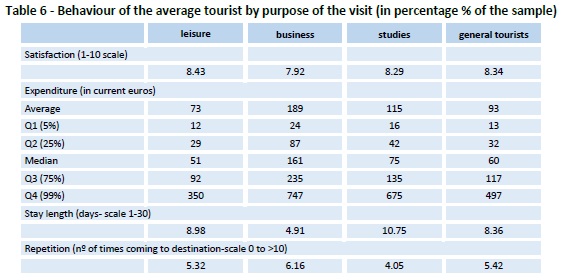

Regarding the behaviour of the average tourists in table 6, overall trip satisfaction is shown to be higher for leisure tourists, although both groups of students and business visitors show high values in the overall satisfaction scale of around 8 out of 10. The distribution of expenditure shows higher average levels of spending for business tourists, followed by students, and leisure ones. For the average tourist, the ratio is of 2.6 between the business and the leisure´s daily spending, and of 1.6 between the studies and leisure´s tourists one. For the median tourist these ratios account for 3.13 and 1.47, respectively, while in the upper tail (Q4 case) they account for 2.13 and 1.92, respectively. Daily expenditure is shown to be up to 747 for business visitors, 675 for students while in vacation, and 350 for leisure trips. Duration of stay is remarkably lower for business trips, with 4.91 days on average, nearly double, around 9 days, for leisure tourists, and 10.75 days in average for students. Business visitors are the highest repeaters in the sample, followed by leisure and studies´ travellers, respectively.

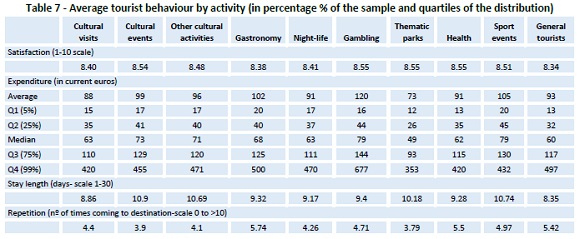

The behaviour of the tourist by holiday activity in table 7 shows that the level of trip satisfaction is higher for those engaged with cultural events, gambling, thematic parks, and health activities, although the rest of activities show higher satisfaction level of tourists in general, all above 8 in a 10-point scale. In any case all selected activities overcome the full sample level of declared satisfaction that stays at 8.34 points. The distribution of spending of tourists shows higher levels in the case of gastronomy, gambling, and sport events, followed by cultural events, and other cultural activities. In the Q4 (fourth quartile) case, gambling, gastronomy, and cultural activities show levels of daily spending that range between 677 and 420 euros. Duration of stay I shown to be the highest in the case of cultural events and activities, sport events, and thematic parks, and the lowest for cultural visits. However, all these stays range between 8.8 and 10.9 days. The highest repeaters can be found on tourists engaged with gastronomy and health activities, while the lowest are among those coming to visit a thematic park and cultural events.

3. Methodology

3.1 Measuring the probability of being a tourists pursuing cultural activities

In this section we define the methodology employed to analyse the variables influencing the probability of a visitor to become a cultural tourist, defined as a tourist doing cultural visits, participating in spectacles and events, as well as being engaged in other cultural activities. In the analysis, we employ a probit model, where the probability of a given event is explained according to a set of explanatory factors. The bivariate probit model is a very well-known one, so we will just mention that in our case the model is defined for capturing the probability that an event (e.g. to be a tourist doing cultural visits) is different from zero, that is, obtains a positive response (Wooldridge, 2010). In particular:

The set of explanatory variables include characteristics of the profile of the tourist, some on the trip itself, plus time and destination sets of dummy variables for the regions and period of analysis. Particularly, covariates of the model include the following ones:

Profile of the tourist: Dummy variables for the country of residence of the visitor (EU countries, Canada, Japan, USA, Rest of Europe, Rest of the World). We also include dummy variables for level of studies (primary, secondary, tertiary), age (15-24 years old, 25-44 years, 45-64 years, more than 64 years), income level (high, middle, low), and gender of the tourist.

Trip characteristics: Dummy variables for first visitors, length of stay (1-3 days of stay, 4-10 days, more than 10 days), type of accommodation (rent house, camping, family house, hotel, second-home, other accommodation), purpose of the visit (leisure, business, studies), season of the trip (four seasons), and for those visitors coming in their own car to the destination, as a way of approaching tourists coming from closer places (greater familiarity with the destination). We also include variables capturing some activities developed on the trip that usually act as a complement of cultural activities (health, gastronomy, gambling), as well as the use of internet for tourists when planning their holidays (for general info, or for booking purposes of accommodation and trip activities).

Destination dummies: One for each of the five regions of the Spanish Mediterranean (Andalusia, Balearic Islands, Catalonia, Murcia, Valencia), in order to control for all their specificities (image, attributes, concept of place).

Overall trip satisfaction declared by the tourist: We include this variable in order to see how it influences the probability of being a cultural tourist. It is defined for a 1-10 points Likert scale, from least (1-7) to most (8-10) satisfied tourists.

4. Results

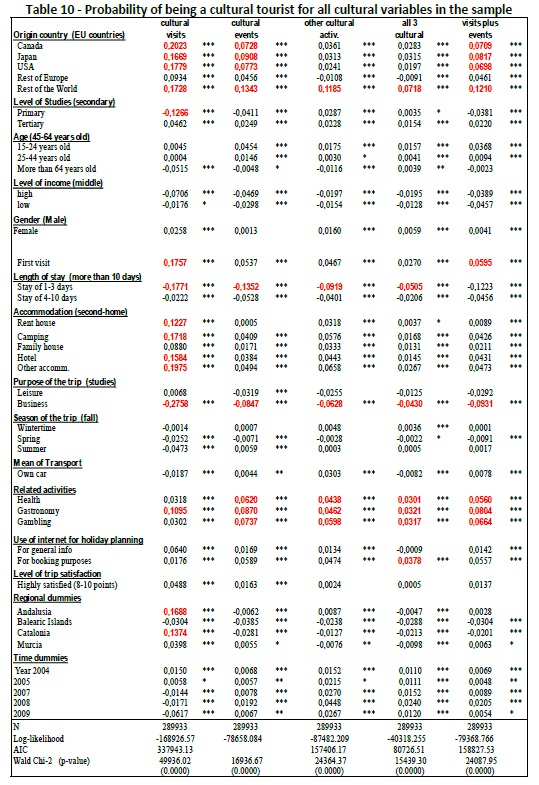

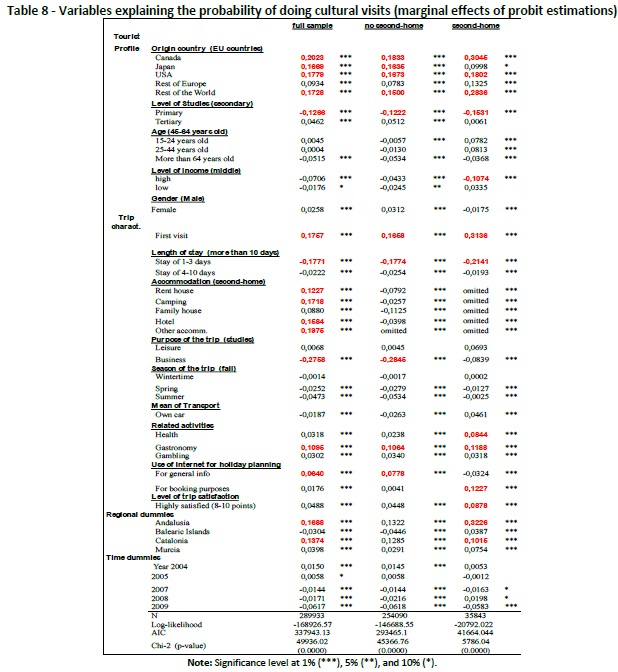

Explanatory factors in the model include variables concerning the profile of the visitor, characteristics of the trip, and destination and time dummies as control variables. Given that the tourists making cultural visits represent the bulk of the sample we will start with this case, then extending the results for the other two cultural cases. Results of the estimation are presented in table 8 in terms of marginal effects for the individual variables, and their corresponding level of significance. The category of reference of the model, to avoid perfect multicolinearity, is defined as a tourists coming from the EU countries, with secondary education, 45-64 years old, middle level of income, male, not coming for the first time to this destination, staying for more than 10 days, employing his/her second-home as accommodation, coming for the studies purpose, in autumn season, visiting the Region of Valencia, and arriving in the year 2006. In general, the base model behaves quite well, showing some variables to be more relevant than others in explaining the probability of being a cultural tourist. Significance of the whole specification of the model is of 100% according to the Chi-2 test, estimation method includes errors robust to heteroscedasticity, and almost all individual variables appear to be significant at the 99% level. For the general, full sample, case, the probability of being a tourist doing cultural visits is shown to increase, in this order, for non-EU tourists, first-time comers, non-second-home accommodated ones, and those non-coming for business purposes. These results seem conferring a relevant role to cultural visits in attracting new, and distant, visitors to this place of Spain, either for leisure or studies purposes. Probability of being a cultural tourist also improves when the duration of stay is not a very short one (1-3 days), when the visitor chooses to do gastronomy consumption too, and when the regions of visit are prominently those of Andalusia and Catalonia. Finally, the probability of a cultural sensibility increases with the level of education, also being promoted when the tourist employs the Internet for obtaining general info in holiday planning.

(clique para ampliar ! click to enlarge)

As some studies point to significant differences in the behaviour of tourists having or not second-homes at destination, we study this case in table 8 too. The following two columns of table 8 present the results on the probability model of doing cultural tourism for these two groups of tourists. Results for visitors without a second-home show just slight differences versus the general case, as they include 87% of the full sample visitors. Being a tourist of the youngest age (15-24 years old) now reduces the interest for cultural visits, while Andalusia and Catalonia also show slight reductions in their fixed effects. In the case of second-home owners, being Canadian or a citizen from the Rest of the World remarkably increases the probability of being a cultural tourist, highlighting in this way the huge role played by culture as an attractor for visitors of these distant areas. For these second-home tourists a lower level of education reduces attraction for cultural visits, as well as having a higher level of income, or staying for the shortest period of time. In contrast, the model shows an increase in the probability of being a cultural tourist particularly for first-time visitors, those doing health activities, employing Internet for booking purposes when planning holidays, visitors with a higher level of trip satisfaction, or visiting the region of Andalusia.

Following with the probit model for cultural activities, now we compare the general full sample case with those split up by purpose of the visit (leisure, business, studies) in table 9, as they use to be very dissimilar type of tourists as pointed out by the literature. Results in the table show that in this case leisure tourists are those more similar to the full sample case, as they account for 81% of the full sample data, while business and student visitors account for 16% and 3%, respectively. Variables determining the probability of doing cultural visits for leisure tourists, versus the general case, are more markedly those of coming from non-EU countries, and going to Andalusia and Catalonia. Coming for a shorter stay (1-3 days) has a lower negative effect than in the general case model. For business tourists, intrinsic variables increasing the probability of doing cultural activities are those of being an older visitor (more than 64 years), and female, while those reducing the probability include having a low level of income, staying for the shortest period of time (1-3 days), and coming with your own car. In the case of students, intrinsic variables increasing that probability are those of renting a house, coming with your own car, and employing Internet for booking purposes, while those decreasing include having primary level of studies, being of an older age (more than 64 years), with high level of income, short stayer (less than 11 days), or doing health activities.

Further, we present the results of the probit model for the other two items on cultural issues, that is, “assisting to cultural spectacles and events”, and doing “other cultural activities”. Results in table10 show that in comparison with doing cultural visits, the probability of assisting to cultural spectacles and events differs in the role of some variables. Basically the most important variables are those of length of stay, purpose of the trip, country of origin, and activities developed. However, some variables loose explanatory power regarding the cultural visits´ case, i.e. those of coming from a non-EU country, the level of income, coming for the first time, being for a shorter stay, the accommodation type, purpose of the trip, and regional dummies. In the case of tourists pursuing other cultural activities” the most relevant variables appear to be those of coming from the rest of the world, duration of stay, and activities developed.

The last two columns of table 10 present results for tourists pursuing all three cultural activities, as well as for those pursuing cultural visits plus events. The former group accounts for 4.1% of the sample, while the latter does it for 10% of it. In the case of tourists doing all three cultural activities, main explanatory variables are those of coming from the rest of the world, doing other activities or using the Internet. For visitors pursuing cultural visits and events, main variables are those of coming from non-EU countries, arriving for the first time to the destination, and not coming for business purposes.

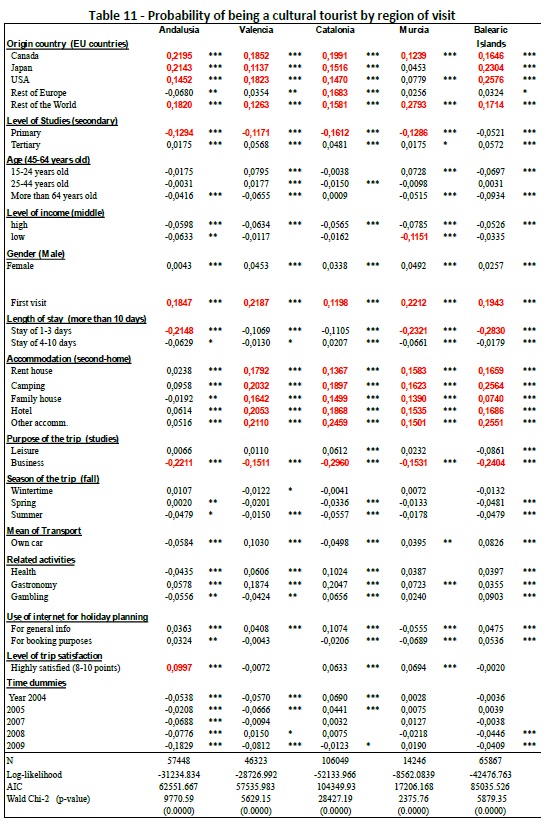

Table 11 allows us to compare the main differences and similarities arising between the five destinations analysed in this study. Results show that first visitors are more prone to be cultural visitors in the case of Valencia and Murcia, shorter stays reduce the probability of doing cultural activities mainly for Balearic Islands, Murcia and Andalusia, type of accommodation is not important in the case of Valencia, business travellers are less prone to culture in the case of Valencia, Balearic Islands and Catalonia, while satisfaction is more important for cultural tourists in the case of Valencia.

As a general result, the investigation has been showing how culture has become an important attractor for non-EU visitors in the Mediterranean region. Indeed, the cultural supplies and local heritage are one of the most relevant competitive advantages of the Euro-Mediterranean tourism sector. Cultural tourists are more prominently first-time visitors, stay for a longer number of days, become engaged in other activities such as gastronomy, and arrive for leisure purposes. Main destinations for cultural tourists are those of Andalusia and Catalonia, with cultural visits, events, and other activities becoming central variables for ensuring the sustainability of the tourism sector in the Spanish Mediterranean region.

5. Conclusions

Cultural tourism in a wider sense has been acting as a powerful engine of the tourism and hospitality industry in the last two decades at the European level. This type of tourism not only provides increasing levels of income to European destinations, but also allows promoting a growing quality and sustainability in the development of tourist activities, enriching the quality of life of local residents. This paper has focused on identifying some of the factors that promote the presence of cultural tourists at five Spanish well-established seaside destinations. Explanatory factors have included a set of variables containing information on the profile of visitors, trip characteristics and activities pursued during the holiday period, plus some control variables including the region and year of the visit. As seaside destinations show a level of maturity in their tourism life cycles, cultural activities could be good candidates for renewing their tourism offer, and the profile of visitors they attract.

In order to enrich our knowledge on the issue we have applied probit models to our data set, running the analysis for a number of segments of the sample, including those of the purpose of the visit (leisure, business, studies), the property or not of a second-home at the destination, the type of cultural consumption carried out (cultural visits, events, or other type of cultural activities), and the region of the visit. General results have shown the leading role that these types of cultural activities play in attracting extra-EU visitors, as well as new (first-comers) to this area. Cultural tourists also show higher probability of staying for a longer time at destination, being mainly engaged into leisure and studies trips. Gastronomy activities, defined by some authors as another type of culture- related activity, clearly appear as a natural complement of cultural activities. The use of Internet when planning the trip is also an important resource of visitors pursuing cultural activities. Andalusia and Catalonia appear as the most visited cultural destinations of the Spanish Mediterranean area, given the big supply of heritage, local culture, and urban-related assets that these regions offer. Other relevant results include the positive relationship arising between the level of education of visitors and their engagement with cultural trips, and the lower presence in cultural tourism of visitors having a second- home at destination.

For specific segments of the sample we have also obtained interesting results. On one side we have seen the role played both by the Internet and trip satisfaction for second-home owners when engaged in cultural activities. On the other side results have shown the particular role of the level of income, being female, or coming with your car to the destination, for those cultural visitors in trips for business and studies. Differences between the five regions under study regarding the factors influencing the surge of cultural visitors have been also stressed by the investigation.

Building on results from the paper, a number of policy issues can be identified. In the case of the sustainability of tourist

destinations we have seen that visitors coming for cultural activities spend more in average than general visitors, stay for longer time, and show higher levels of overall trip satisfaction. They also attract a higher relative number of new visitors from extra-EU countries, of first-time visitors, and of those with higher sensitivity linked to higher levels of studies, in comparison with the general tourists visiting this area. All these features identified in the culturally engaged international visitors would be willing to provide a richer environment for indigenous residents, reducing in this way the typical damaging impact of mass tourism on local population. Results also suggest that promoting and developing cultural tourism is a desirable policy, resulting in a growing number of visitors, and a corresponding positive impact at destinations, either economic, social or cultural. The importance of the promotion of cultural tourism at the level of destination has become clear along the investigation. Catalonia is undoubtedly one destination highly investing in the promotion and development of cultural tourism in the last two decades. Andalusia has also allocated important resources in these types of activities, valuating the cultural heritage and investing in the promotion of their intangible cultural traditions as i.e. enjoying the street life. The success of these policies has been shown by data, with these two regions appearing as the preferred destinations of cultural visitors in the Spanish Mediterranean area. The growing role of the Internet for promotion policies for cultural visitors has also been pointed out by results in the paper. Other opportunities of attracting new arrivals seems to arise for business visitors and shorter-stayers as interesting targets for the future. Gastronomy also appears as an important factor of attraction for new visitors with an important level of complementarity with cultural supplies in the development of the tourism sector.

In general, as shown by the investigation, culture appears as a pivotal asset of the tourism industry for the near future. Increasing cultural tourism allows maintaining and improving the heritage and cultural supplies of destinations, making local residents more prone to support such an economic activity. Moreover, culture reduces the important seasonality patterns linked to seaside destinations, and helps to renew the tourism offer of such mature locations, increasing in this way the sustainability of the Mediterranean regions of Spain, but also of many other places alike along the world tourism market.

REFERENCES

AEC (2015). Anuario de Estadísticas Culturales (2015). Madrid: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte de España. [ Links ]

ETC (2005). City Tourism and Culture. Brussels : European Travel Commission. [ Links ]

Europa Nostra (2016). Retrieved 16 June 2016 from http://www.europanostra.org/attracting-new-tourists-flows-ensuring-protection-cultural-heritage/

European Commission (2007). Agenda for a sustainable and competitive European tourism. COM Document (2007), 621 final, Brussels: Commision of the European Communities. [ Links ]

Getz, D. (2008). Events tourism: Definition, evolution and research. Tourism Management 29, 403–428. [ Links ]

Hjalager, A-M., & Richards, G. (2002) (eds.). Tourism and Gastronomy. London: Routledge.

May, J. (1996). In search of authenticity off and on the beaten track. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 14(6), 709–736. [ Links ]

McKercher, B., & du Cros H (2002). Cultural Tourism: The Partnership between Tourism and Cultural Heritage Management. New York: The Haworth Hospitality Press. [ Links ]

OECD (2009). The Impact of Culture on Tourism. Paris: OECD. [ Links ] OECD (2014). Tourism and the Creative Economy. Paris: OECD. [ Links ]

Richards, G. (1996). Cultural Tourism in Europe. Wallingford: CABI. [ Links ]

Richards, G. (2001). Cultural Attractions and European Tourism. Wallingford: CABI. [ Links ]

Richards, G. (2011). Creativity and tourism: The state of the art. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(4), 1225–1253. [ Links ]

Richards, G., & Palmer, R. (2010). Eventful Cities: Cultural Management and Urban Revitalisation. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Richards, G., & Wilson, J. (2006). Developing creativity in tourist experiences: A solution to the serial reproduction of culture? Tourism Management, 27(6), 1408–1413. [ Links ]

Ritzer, G. (1999) Enchanting a Disenchanted World: Revolutionizing the Means of Consumption. London: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Stone, P. R. (2006). A dark tourism spectrum: Towards a typology of death and macabre related tourist sites, attractions and exhibitions. TOURISM: An Interdisciplinary International Journal, 52(2), 145-160. [ Links ]

Timothy, D. J., & Boyd, S. W. (2003). Heritage Tourism. London: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

UNWTO (1985). The Role of Recreation Management in the Development of Active Holidays and special Interest Tourism and the Consequent Enrichment of the Holiday Experience. Madrid: United Nations World Tourism Organization. [ Links ]

UNWTO (2014). World Tourism Organization Annual Report 2013. Madrid: United Nations World Tourism Organization. [ Links ]

Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. Cambridge (Mass): The MIT Press. [ Links ]

Received: 11 January 2017

Revisions required: 12 June 2017

Accepted: 23 September 2017

Acknowledgements:

Prof. Andres Artal-Tur wishes to thank financial support from Group of Excellence Program of Fundación Seneca, Science and Technology Agency of the Region of Murcia, project 19884/GERM/15.