Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.14 no.1 Faro mar. 2018

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2018.14106

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Birdwatcher profile in the Ria Formosa Natural Park

Perfil dos observadores de aves no Parque Natural da Ria Formosa

Andreia Costa*, Pedro Pintassilgo**, António Matias***, Patrícia Pinto****, Maria Helena Guimarães*****

*University of Algarve, Faculty of Economics, Campus de Gambelas, 8005-139 Faro, Portugal, a_sofia22@hotmail.com

** University of Algarve, Faculty of Economics and and Center for Advanced Studies in Management and Economics (CEFAGE), Portugal, ppintas@ualg.pt

*** University of Algarve, Faculty of Economics and Research Centre for Spatial and Organizational Dynamics, Portugal, amatias@ualg.pt

**** University of Algarve, Faculty of Economics and Research Centre for Spatial and Organizational Dynamics, Portugal, pvalle@ualg.pt

***** University of Évora, Landscape Dynamics and Social Processes Group, Instituto de Ciências Agrárias e Ambientais Mediterrânicas (ICAAM), Portugal, mhguimaraes@uevora.pt

ABSTRACT

In the Algarve the potential for birdwatching tourism is widely recognized, especially in the Ria Formosa Natural Park (RFNP). This study aims to describe birdwatchers’ profile in the RFNP. For this purpose, a survey was applied. The results show that the most frequent nationalities of birdwatchers are: British (39%), Dutch (17%) and Portuguese (17%). The majority of birdwatchers are male (55%) and married (57%). The average age is 50 years old. They are highly educated (74% have an academic degree). Concerning profession, the most frequent answer was retired (41%). Respondents are committed to the activity as the majority possess special equipment and practice birdwatching in vacations. This study also tests if nationality is related to other characteristics of the birdwatchers, by using the Kruskal-Wallis and the Chi-square tests. Overall, the results of this study highlight that regional management organizations should invest in developing birdwatching in the RFNP.

Keywords: Birdwatching, birdwatcher profile, Environmental awareness, Ria Formosa, Algarve.

RESUMEN

O potencial para o turismo de birdwatching é vastamente reconhecido, especialmente no Parque Natural da Ria Formosa (PNRF). Este estudo tem como objetivo descrever o perfil dos observadores de aves que visitam o PNRF. Para esse propósito, foi aplicado um questionário. Os resultados mostram que as nacionalidades mais frequentes dos observadores de aves são: britânica (39%), holandesa (17%) e portuguesa (17%). A maioria dos observadores de aves é do sexo masculino (55%), sendo o seu estado civil casado (57%). A idade média é de 50 anos. O seu nível educacional é elevado (74% têm um grau académico). Quanto à profissão, a resposta mais frequente foi aposentado (41%). Os inquiridos estão comprometidos com a atividade, pois a maioria possui equipamentos especiais e pratica observação de aves nas férias. Este estudo também testa se a nacionalidade está relacionada com outras características dos observadores de aves, através de testes Kruskal-Wallis e Qui-quadrado. Os resultados deste estudo indicam que as organizações de gestão regional devem investir no desenvolvimento do birdwatching no PNRF.

Palabras clave: Birdwatching, perfil do observador de aves, consciência ambiental, Ria Formosa, Algarve.

1. Introduction

Birdwatching tourism is currently a very dynamic activity. In particular, it is starting to be explored in places where it is still underdeveloped but with high biodiversity (Czajkowski, Giergiczny, Kronenberg & Tryjanowski, 2014). The rapid growth of this activity makes it more important for the stakeholders of the industry to understand in which way tourists interact with the surrounding environment (Moore, Scott & Moore, 2008).

If we analyse the figures of the birdwatching market in the world, we come across with estimations that point out the existence of around 100 million birdwatchers. In the USA, which is one of the biggest markets of birdwatching, the number of birdwatchers in 2006 was about 47.7 million adults (around 21% of the population), while the economics benefits of the activity (direct and indirect) ascended to over $85 billion (Moore et al., 2008). In Europe, the United Kingdom is the biggest market with 2.4 million birdwatchers (Ministro & Miguel, 2009). Birdwatching is also gaining importance in Mediterranean countries such as Spain, Italy and Portugal (Turismo do Algarve, 2012).

This study is about birdwatching in a particular protected area at the coast of the Algarve. Ria Formosa Natural Park was chosen because it is characterized by a wetland very rich in biodiversity and wildlife. It is already attracting tourists to do birdwatching, but still, it has not yet an integrated offer (Ministro & Miguel, 2009). Some studies about the potential of the Algarve for birdwatching resulted in the production of dissemination materials such as birdwatching guides and flyers, where RFNP was highlighted as one of the best hotspots. This demonstrates that tourism organizations recognize that RFNP is able to attract birdwatchers. However, to the best of our knowledge, not must research has been undertaken on birdwatching in the area. Most studies focusing on this location are about marine sciences and biology and very few address the economic importance of activities like tourism, that depend on the conservation of this area. Therefore, the present study aims at contributing to overcome this knowledge gap.

The objective of this study is to describe the birdwatchers profile (including tourists and excursionists) in the RFNP. In particular, it intends to identify the reasons why birdwatchers come to this specific location, their satisfaction level, birdwatching background and socio-economic characteristics. To achieve this a face-to-face survey was conducted at “Quinta de Marim” – a pedestrian trail where all the habitats present in the park are represented, which in statistical terms can be regarded as a cluster. Moreover, two hypotheses are tested to comprehend if nationality is related with other characteristics of birdwatchers’ profile. The hypotheses are:

(1) The number of days of birdwatching per year has the same distribution within the different nationalities; (2) The practice of birdwatching in other places of the Algarve is independent of nationality. Hence, the study aims to contribute to a better knowledge of the birdwatcher profile in the RFNP. The importance of such characterization reaches policy-making since by understanding what birdwatching visitors want to see and do, policies can be designed to improve the quality of the birdwatching experience (Green & Jones, 2010).

2. Literature review

Birdwatching is included in the wildlife tourism which is defined as an activity where tourists have the opportunity to observe or interact with wildlife (animals, plants and habitats) that might be endangered, threatened or rare (Ballantyne, Packer & Hughes, 2009). According to Reynolds and Braithwaite (2001), within the wildlife tourism products there are seven categories where most activities can be placed: (1) Nature-based tourism with wildlife component; (2) Locations with good wildlife opportunities; (3) Artificial attractions based on wildlife; (4) Specialist animal watching; (5) Habitat specific tours; (6) Thrill-offering tours; and (7) Hunting/fishing tours. Birdwatching is included in number (4) as it is characterized by tours for those who are interested in a species or group of species, in this particular case: birds. In the words of Roig (2008:102) birdwatching is: “A journey whose purpose is to engage in leisure activities involving ornithology, namely the detection, identification and observation of avifauna, with the objective of being in contact with nature to satisfy educational needs and/or achieve personal satisfaction”.

Birdwatchers are those who practice birdwatching activities. This group is characterized as being diverse in terms of socio- economic characteristics, motivations and preferences (Lee, Lee, Jin-Hyung, Tae-Kyun & Mjelde, 2010). Such variety translates into the existence of different birdwatchers’ typologies. Wright (1995) identified two categories: experts and occasional birdwatchers. Later, Jones & Buckley (2001) took into account the motivations and the willingness to pay of birdwatchers and distinguished four categories: general birdwatchers; specialist birdwatchers with restricted budgets; specialist birdwatchers willing to pay to see birds; and specialist birdwatchers requiring packaged birding.

To characterize birdwatchers, the simplest approach is the one purposed by Mogollón, Cerro & Durán (2011) who considers only two groups of birdwatchers attending their specialization level, motivation and logistics restrictions: “birders”, which are less specialized and “twitchers” which are more engaged in the activity. Regarding “birders” their main motivation is the contact with nature and biodiversity, and they practice birdwatching as a complementary activity (Ministro & Miguel, 2009). According to Roig (2008) the majority of birdwatchers are included in this group. On the other hand, “twitchers” have birds as their primary motivation and the observation of birds is the reason of their travelling. “Twitchers” choose the locations considering the species they can see there. They have the goal to increase their personal list of observed bird species and overcame other “twitchers” (Roig, 2008). Their bird knowledge is above average and they are competitive, sometimes having a degree of hierarchical social structure and stages of development (Connell, 2009). “Twitchers” are often demanding regarding accommodation and tourism services (Roig, 2008).

Several studies have been made worldwide to determine birdwatcher profile, with special focus on the USA market. Cole & Scott (1999) characterized the members of American Birding Association with an average age of 65 years old, high income and education levels. Scott & Thigpen (2003) have studied the Hummingbird Celebration in Rockport Texas. They concluded that birdwatchers in the area were mostly females (76%), 66% of the respondents had over 46 years old, 75% were married and a rate of 57% were university graduates. The majority belonged to middle to upper classes with a household income of 40 000$/annual or more. Moreover, about 34% were already retired. Another study conducted in Nebraska, Texas, New Jersey and California (Eubanks Jr, Stoll & Ditton, 2004) concluded that birdwatchers were homogeneous in terms of gender, age and race. A later survey conducted in North Carolina, Moore et al. (2008) had a sample composed with mostly men (59%), with an average age around 54-years-old and confirmed the high education and income levels.

In Asia and Australia Lee et al. (2010) and Green & Jones (2010) described South Korean and Australian birdwatchers as being equally males and females with higher education than other tourists. In south Queensland birdwatchers were also likely to practice complementary activities such as hiking. Roig (2008) summarized the Spanish birdwatcher profile: 25 to 45 years old; high education level; spend a maximum of 5 days in the area; combine birdwatching with other activities; and spend on average 100€ per person per day.

In Portugal there are not many studies about birdwatcher’s profile and the existing ones are very recent. About international birdwatchers in the Algarve, Machado (2011) found the European market was mainly composed by North Europeans, with high education and income levels, living in urbanized areas and with an average of 55 years old. Guimarães, Nunes, Madureira, Santos, Boski & Dentinho (2014) inquired birdwatchers at Praia da Vitória, Ilha Terceira, Azores. They were able to understand that most birdwatchers in the area stayed 3 days on the site and spent on average 42€ per day on food and accommodation. Also birdwatchers were mostly people in the group age of 39 to 48 years old and earned on average approximately 2400€ per month.

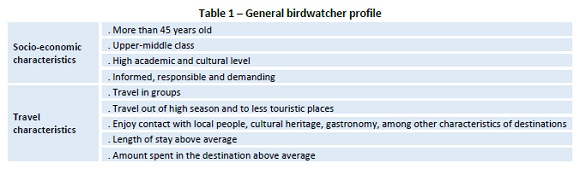

Based on the results of these nine studies, it is possible to resume some general characteristics (Table 1). Generally, birdwatchers are highly educated, have high incomes and have a high environmental consciousness (Connell, 2009). They normally stay more days in the destination and spend more than other tourists. Birdwatchers are well informed people who, besides the central point of bird observation, look to have contact with locals, discover the cultural heritage and local gastronomy (Ministro & Miguel, 2009). About gender, women are increasingly more engaged in the activity, so nowadays there is almost no difference between the number of men and women doing birdwatching (Machado, 2011).

As birdwatchers are a heterogeneous group, the supply of birdwatching tourism services is very diverse. For example, tours offered by birdwatching operators vary from intensive, hard trekking and with long wait to observe birds, to tours where stops are made to see the scenery and where birds can or cannot be spotted (Jackson, 2007).

3. Methodology

3.1 Study site

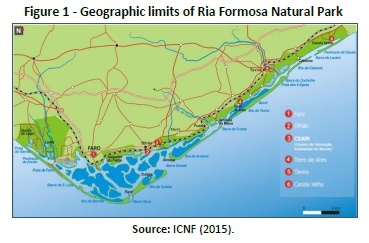

The Ria Formosa Natural Park (RFNP), located in the south-east coast of the Algarve, is one of the most important wetlands in Europe (Ceia, Patrício, Marques & Dias, 2010) (Figure 1). The importance of wetlands is recognized globally. In Europe, these constitute only 3% of the total territory. Its importance is related with the fact that it is one of the most productive ecosystems in the world, essential to several species of aquatic birds (Amaral, 2009). The climate in the RFNP is of Mediterranean type with long, hot, dry summers and mild winter (Vowles & Vowles, 1994). Temperatures are mild all year around, with a mean of 25ºC in the summer and 12ºC in the winter (Newton & Mudge, 2003). On the economic dimension, RFNP supports many activities, like, fishing, aquaculture, shipping, harvesting of bait, tourism, salt production and sediment extraction (Ribeiro et al., 2008).

The RFNP is included in the National Network of Protected Areas and its protection status was created by Decree-law nº 373/87, of 9th December, in 1987. The place was classified as a Natural Park to protect the existing natural values, to contribute to regional and national development, and to ensure the adoption of measures compatible with the objectives of the Natural Park. This protection status includes all the lagoon system, its fauna, flora and habitats, and it protects also the migratory species (Ministério do Plano e da Administração do Território, 1987). The protected area extends for 60 kilometers occupying around 18 400 ha, 7 895 ha of which are inland and 10 505 ha wetlands crossing five municipalities (Loulé, Faro, Olhão, Tavira and Vila Real de Santo António) (Amaral, 2009).

The RFNP is characterized by coastal sandy dunes that protect a lagoon forming a variety of natural habitats: barrier islands, mudflats, dunes, salt marshes, freshwater ponds and brackish water, waterways, forests and agricultural areas (Ceia et al., 2010). These environmental characteristics make RFNP a place rich in biodiversity. To protect its biodiversity, Ria Formosa received several classifications that recognize its environmental importance, such as, Special Protection Area for Birds, Rede Natura 2000, Ramsar Site and Important Bird Area (IBA) (Sociedade Polis Litoral, 2010). Some of the protection classifications are specific for birds. The RFNP has a big variety of birds and also some protected and emblematic species. It is a nesting zone and it has international importance for migration of birds (Ceia et al., 2010) along with other biological and ecological functions like offering food and shelter for many species (Sociedade Polis Litoral, 2010). Many species choose its salt marshals to breed or to rest during migration. The geological and water characteristics (like the simultaneous presence of fresh water, salt water and brackish water) make it possible the coexistence of a large variety of bird species (Amaral, 2009). These characteristics make the wetland appealing for birdwatchers (Turismo do Algarve, 2012).

3.2 The survey

A face-to-face survey was applied in order to characterize birdwatching visitors. The survey was conducted in the natural trail of “Quinta de Marim”. This is the only trail that is clearly delimitated with fences and where it is necessary to pass through a reception point. Inside the area there is a Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre with an environmental interpretative Centre. This was the place where the survey was applied when visitors stopped to see the exhibition and rest. All types of birdwatchers from experienced ones to the general visitor who did a bit of birdwatching were included in the study. The questionnaires were applied on different days of the week and different hours of the day to reduce possible biases in the sample (Tisdell & Wilson, 2004). Those who answered the questionnaire were engaged in participating in birdwatching activities and were over 18 years old.

Considering that people were in their leisure time, the questionnaire was short and could be filled in less than ten minutes. Questions were both multiple choice and open-ended. The questionnaire had 33 questions divided in three major sections: Birdwatching in the Ria Formosa Natural Park; Birdwatching Background; and Background Information. The first section aimed to understand birdwatchers’ motivations and their opinion about the park experience. Therefore, respondents were asked how many times they have been there, with whom and for how long. They were also asked about the main reason for the visit. Questions about satisfaction, intention to return and willingness to recommend the park to friends and family were also part of the first section. In the second section, respondents were questioned about habitats related with birdwatching as it is important to understand the level of commitment with the activity especially in this study that included all types of birdwatchers. Questions like the use of special equipment (e.g. bird field guide or telescope) and the number of days dedicated to this activity per year were posed. At last socio-economic data is crucial to define the sample characteristics. This section included questions about nationality, gender, age, education level and monthly household income. This section was important to understand if socio-economic characteristics influenced individual’s birdwatching behaviour (Machado, 2011).

A pre-test was applied during five days in October 2014 and a total of 12 questionnaires were answered. A random sampling was applied in “Quinta de Marim”, which is a site with similar characteristics to the rest of the park. The survey was available in four different languages: English, Portuguese, Spanish and Dutch. The questionnaire was applied during the months of November 2014 and February, March and April of 2015, to include bird migration periods. A sample of 203 birdwatchers was reached. Out of these, 18 were excluded: three because were very incomplete and fifteen because respondents were not birdwatchers. A total of 185 valid questionnaires were obtained, corresponding to 91.1% of the selected sample.

3.3 Data analysis methods

To analyze the data collected the SPSS Statistics 21 program was used. Descriptive statistics and hypotheses testing were undertaken. The descriptive statistics was used to do an initial characterization of the sample by describing the profile of the birdwatchers in the RFNP. This included frequency tables, means and cross tabulations. Then it was tested the influence of nationality in two different aspects: days per year dedicated do birdwatching (H1), and the visitation of other sites in the Algarve (H2). To test hypothesis 1, the Kruskal-Wallis H-test was chosen. The Chi-square test was performed to compare the nationalities and their relation with the practice of birdwatching in other sites in the Algarve (H2).

4. Results

4.1 Socio-economic characteristics

The profile of the birdwatcher in “Quinta de Marim” was characterized by using several socio-economic variables. The majority of the respondents are British (39.1%), followed by Dutch (17.4%) and Portuguese (16.8%). Other important nationalities are Belgian (6%), Spanish (6%) and German (4.9%). Except for four Canadians and one Australian, all respondents are European. Regarding country of residence, 36.4% of the respondents live in the United Kingdom and 22.3% in Portugal. This means that almost 60% of the birdwatchers in “Quinta de Marim” come from these two countries. It also demonstrates that there are some foreign birdwatchers living in Portugal.

Plus, the results show that the birdwatchers that live in Portugal are mainly from Faro county (63.4%).

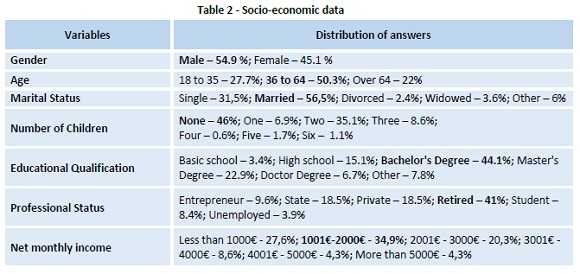

Other main socio-economic characteristics of the birdwatchers surveyed are provided in Table 2. Men are more frequent (54.9%) than women, but the difference in gender is not very accentuated. The average age is 50 years old. The majority of the sample is married (56.5%). About 46% have no children. Education level shows that respondents are highly educated, with only 26.3% not having a university degree. About 44% of the respondents have a bachelor’s degree and 22.9% a master’s degree. As for professional status, the most frequent is retired (41%). Employed by the state and employed by the private sector show an equal percentage (18.5%). Regarding individual net monthly income, the most frequent class is 1001€ to 2000€ (35%) and about 17% of birdwatchers earn more than 3000€. The median net monthly income is 1640€.

4.2 Birdwatching in the Ria Formosa Natural Park

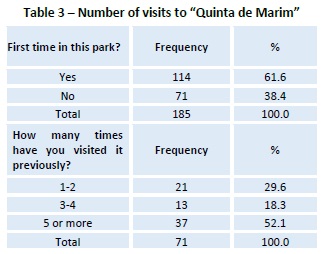

Table 3 shows the number of visits to “Quinta de Marim”. Around 62% of the respondents went there for the first time. Nevertheless, 52.1% of those who have been there before have visited the park five or more times, 18.3% from three to four times and 29.6% from one to two times.

To understand if there is a relation between the answer to “first time in this park?” and the nationality of the visitor a Cross- tabulation was performed. As expected, due to proximity, most of Portuguese have visited the park previously (70%). Regarding foreigners, only 32% of the visitors from other nationalities have been in the park before. The percentage is higher among British individuals (40%).

Regarding the reason why people go to the park, the large majority claims that the primary reason is to do birdwatching (70%). Other primary reasons to visit the place are: nature (9%), walking (4%), professional or scholar reasons (3%) and wildlife (2%). This question was open ended and several respondents left it blank.

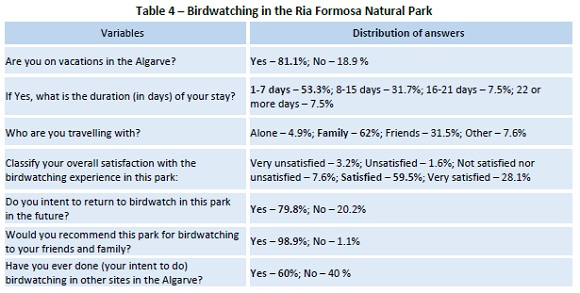

On Table 4 some aspects about the travel, birdwatching in the area and overall satisfaction are presented. Around 81% of the respondents are on vacations in the Algarve. On average, birdwatching visitors spend 14 days in the Algarve. This data was categorized into four classes, to better analyse it. This procedure showed that 53.3% of the respondents spend one week or less in this destination and only 7.5% stay more than 3 weeks. Birdwatchers travel mostly with family (62%) or friends (31.5%). The overall experience in “Quinta de Marim” is positive, as 87.6% of the respondents are satisfied or very satisfied with the birdwatching experience; 79.8% show interest to return and almost 99% would recommend the site to family and friends.

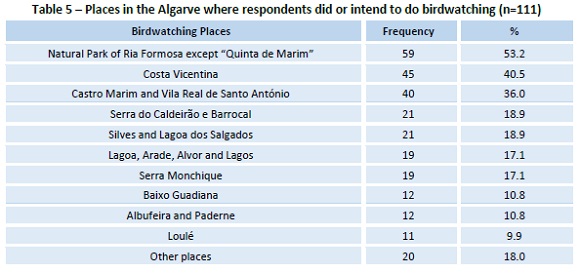

Most respondents have already done or intend to do birdwatching in other places in the Algarve (60%). This means that birdwatchers like to visit several places in the destination. Those who answered that they have already done or intend to do birdwatching in other places in the region were then asked about which other locations they had visited or intend to visit, through an open ended question. The answers were classified according to the birdwatching places in the Algarve defined by Ministro & Miguel (2009). Several respondents answered more than one place. The most referred places were other sites in the Natural Park of Ria Formosa (53.2% of the 111 respondents who have already done or intend to do birdwatching in other places in the RFNP), Costa Vicentina (40.5%) and the areas of Castro Marim and Vila Real de Santo António (36.0%) (Table 5).

4.3 Birdwatching background

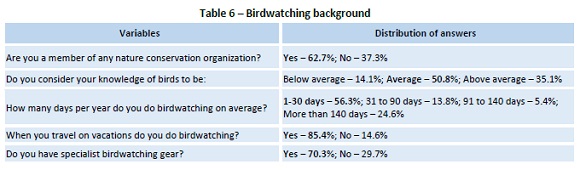

Table 6 shows several aspects of the birdwatching background, which is important to understand the commitment to birdwatching of the respondents. The majority of the respondents are members of nature conservation organizations (62.7%). Among them are Portuguese organizations, such as SPEA and ALDEIA, and organizations based abroad, such as The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) (UK), Wildfowl & Wetland Trust (UK), Vogelbescherming (NL) and Natuurmonumenten (NL). Most of the respondents consider themselves with average knowledge of birds (50.8%) and a significant percentage considers themselves as being above average (35.1%).

On average respondents do birdwatching 95 days per year. It should be noted that around 25% of the respondents do birdwatching more than 140 days per year. The mode is 10 days per year and 56.3% of the respondents do 1 to 30 days of birdwatching per year. A high percentage of the respondents do birdwatching during vacations (85.4%). Also a significant percentage affirms to have specialist birdwatching gear (70.3%). From those, around 91% have specialist binoculars, 79% have bird field guides, and 33.1% a special camera. A minor percentage also has other equipment (6.2%) like recorders.

4.4 Testing the hypotheses

This section aims to analyse if there are behavioural differences among birdwatchers of different nationalities. For that two hypotheses were formulated: (1) The number of days of birdwatching per year has the same distribution within the different nationalities; (2) The practice of birdwatching in other places of the Algarve is independent of nationality. The statistic tests used were the Kruskal-Wallis H (H1) and the Chi-Square (H2).

To test H1 the variable “Nationality” was transformed from its thirteen initial categories into four categories: the three more represented nationalities (British, Dutch and Portuguese) and one category combining all the remaining ones (Spanish, Belgian, German, Canadian, Swiss, Swedish, Danish, Irish, Australian and French). This was done as some nationalities had very few representatives and therefore statistical analysis would not be feasible. In order to understand if the distribution of the number of days dedicated to birdwatching per year changes with the nationality a Kruskal-Wallis H test was performed. This was chosen because the null-hypotheses of the

Levene test, homogeneity of variances, and of the normality test of Kolmogorov-Smirnov were rejected (p-value < 0.05). Results for the Kruskal-Wallis H test shows that there is no significant statistical difference among the distributions of the birdwatching days per year of the different nationalities (chi- square (3) = 5.064; p-value =0.167>0.05). Therefore, we can conclude that nationality does not affect the number of days per year a birdwatcher spends doing birdwatching.

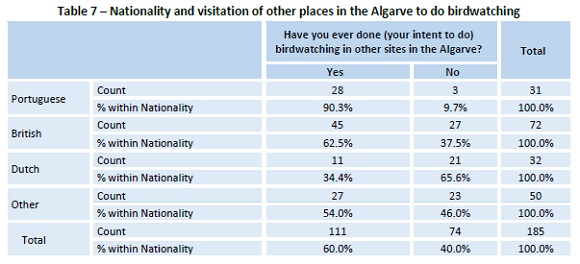

To test H2, a Chi-Square Test was performed. This test was chosen as it examines relationships between categorical variables. This test shows that there is a relationship between the practice of birdwatching in other places of the Algarve and the birdwatcher’s nationality (Chi-Square = 23.617; p-value < 0.001). In order to explore this relationship a cross tabulation was performed (Table 7). The results show that around 90% of the Portuguese birdwatchers have done or intend to do birdwatching on other sites in the Algarve. This percentage is higher than the overall proportion in the sample: 60%. In contrast, only 34% of the Dutch answered “Yes” to this question.

5. Discussion and conclusion

Birdwatching tourism is a growing activity in the Algarve. This combined with the recent acknowledgement by policy-makers that the region has potential in this tourism sector, makes it an important research field. The goal of the study was to characterize birdwatchers at RFNP: to identify the reasons why birdwatchers come to this specific location, their satisfaction level, birdwatching background and socio-economic characteristics.

The results of the survey undertaken at “Quinta de Marim” show that English, Dutch and Portuguese are the most frequent nationalities of birdwatchers, which is in line with the findings

of Machado (2011). This means that British look for more than the traditional “Sun and Beach” tourism in the Algarve. The RFNP has a Mediterranean climate with mild temperatures all over the year which is a plus to attract north European tourists, like English and Dutch. Hence, marketing efforts should be directed to these three countries.

Regarding marital status and occupation this sample meets the results of Scott and Thigpen (2003): birdwatchers are mainly married and a large proportion is retired. The gender follows the general trend of women being equally represented to men in this activity (Machado, 2011). The average age of birdwatchers is 50 years old. Retired birdwatchers have more time to practice the activity all year around. This aspect combined with the fact that birdwatching events in the Algarve are concentrated in spring and autumn (e.g. migration and breeding) makes this activity important to reduce tourism seasonality in the region. Most of the birdwatchers are highly educated (Bachelor’s degree or higher), the median monthly net income is 1640€ and 17% of birdwatchers earn more than 3000€. The literature shows that birdwatchers belong to a middle upper class (e.g. Cole & Scott, 1999; Connell, 2009).

Concerning birdwatching background, respondents are committed to the activity as they have knowledge about birds, possess special equipment and do it when in vacations. The more committed the birdwatcher is, the more demanding and the higher is the interest in certain species. So it is necessary to adapt marketing strategies and develop special materials highlighting rare and emblematic bird species.

The surveyed birdwatchers present an average length stay in the region of 14 days, which is according to the profile of nature tourists in Europe (Turismo de Portugal, 2006). Like the European nature tourists, birdwatchers in the RFNP travel mostly with family or friends. Comparing with the study of Guimarães et al. (2014) in Azores, the average length of stay of birdwatchers is higher in RFNP (14 days) than in Ilha Terceira (3 days).

The birdwatchers in the RFNP tend to return to the location, recommend it to friends and family and in general they are satisfied with the experience. Regarding the overall satisfaction with the birdwatching experience in “Quinta de Marim”, the majority of birdwatchers consider they had a satisfying or very satisfying experience (88%). Nevertheless, only 28% are very satisfied. This means some aspects can still be improved in the RFNP. Several efforts were made recently with the installation of new bird observatories but the trail still lacks bins and cleanness, places to rest in the shadow, information panels on site, complementary activities and services like the rent of binoculars.

Another important finding is that more than 32% of foreigners visiting the park have been there before. The ability to maintain customers is very important as to attract a new customer is more expensive than to keep one. Although there is a high overall satisfaction with the experience it may not be directly related with the intention to return. As Jafari (2003) points out: customer satisfaction and customer loyalty is not the same

thing. The majority of the respondents has visited or intend to visit other areas of the RFNP to practice birdwatching (53%). This shows that the RFNP is an important area for birdwatching in the Algarve. Therefore, police-makers of the region should invest in this type of tourism in order to attract more visitors.

This study did not aim to go deep in the level of birdwatcher specialization by dividing them into birders and twitchers. The objective was rather to characterize the birdwatching background to understand birdwatchers’ commitment with the activity. Most respondents consider themselves to have an average knowledge of birds (50.8%) and they have specialist birdwatching gear (70.3%). The majority dedicates between 1 and 30 days per year to birdwatching. More than 85% practice the activity when in vacations. Therefore, is possible to confirm that respondents are committed to the activity as they have knowledge about birds, possess special equipment and practice the activity when in vacations. This information can help destination managers and tourism organizations to better develop programs and promotional materials appropriate to the needs of the different levels of interest within the activity (Machado, 2011).

Furthermore, hypotheses were tested to evaluate if nationality is an important factor in differentiating birdwatchers in terms of behavioural characteristics. This can help to understand if there are specific markets where it pays to invest. Results showed that there is no relation between the days per year a birdwatcher spends doing birdwatching and nationality. This indicates that Portuguese birdwatchers practice the activity as most as foreigners and therefore they should not be underestimated.

The results also showed that the visitation of other places in the Algarve to practice the activity is related to nationality. Around 90% of the Portuguese birdwatchers have done or intend to do birdwatching on other sites in the Algarve. This high percentage of Portuguese birdwatchers going to other places in the Algarve may be explained by the proximity to the destination. Among foreigners, British are the ones who visit more other places in the region to do birdwatching. Therefore, special attention should be paid to the UK market. It may be less expensive to promote the RFNP as a birdwatching destination to the UK market, when compared to other countries, as British is already the main nationality of tourists in the Algarve.

An advantage of this study is that it covered all types of birdwatchers from casual to serious birders. It also covered migration periods. Machado (2011) only covered more specialized birdwatchers and Amaral (2009) did not cover any migration period.

This study presents some limitations which open opportunities to further research. The most pertinent is the size of the sample and the fact that the questionnaire was only applied in one cluster – “Quinta de Marim”. Considering the birdwatching market at the RFNP or even the Algarve, there is potential to apply the same method to other places/clusters. As the research aimed to cover several aspects of birdwatchers’ profile, it did not gather sufficient information to categorize them into birders and twitchers. This can be done on future research. Another research avenue is to explore if birdwatching development in the RFNP is a form of sustainable tourism.

The survey also had some limitations. Although a pre-test was applied, leading to changes in some questions, some flaws were still identified. The question about satisfaction could have been complemented with a question about the reasons for satisfaction or dissatisfaction. This would be helpful to fully understand the satisfaction of birdwatchers. Regarding the age question, many respondents skipped it. Probably if this question was in categories, rather than open-ended, more people would reveal their age.

The present research can be used as a basis for further studies in the RFNP or even as a comparison to other Portuguese regions, to understand if there are differences in the birdwatcher profile. Moreover, future studies could test the relation between behavioural characteristics of birdwatchers and socio-economic variables other than nationality, such as age and income.

This study suggests that birdwatching tourism has a high potential in the RFNP. Overall, the results point out that the regional management organizations should invest in developing birdwatching in this site.

REFERENCES

Amaral, S. D. (2009). A avifauna como meio de valorização turística da Ria Formosa – Faro. (Unpublished Master’s Thesis). University of Algarve, Portugal.

Ballantyne, R., Packer, J., & Hughes, K. (2009). Tourists’ support for conservation messages and sustainable management practices in wildlife tourism experiences. Tourism Management, 30(5), 658–664. Doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2008.11.003

Ceia, F. R., Patrício, J., Marques, J. C., & Dias, J. A. (2010). Coastal vulnerability in barrier islands: The high risk areas of the Ria Formosa (Portugal) system. Ocean & Coastal Management, 53(8), 478-486. Doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2010.06.004 [ Links ]

Cole, J, S., & Scott, D. (1999). Segmenting participation in wildlife watching: a comparison of casual wildlife watchers and serious birders. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 4(4), 44-61. doi:10.1080/10871209909359164 [ Links ]

Connell, J. (2009). Birdwatching, twitching and tourism: towards an Australian perspective. Australian Geographer, 40(2), 203-217. doi:10.1080/00049180902964942 [ Links ]

Czajkowski, M., Giergiczny, M., Kronenberg, J., & Tryjanowski, P. (2014). The economic recreational value of a white stork nesting colony: A case of stork village’ in Poland. Tourism Management, 40, 352-360. Doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2013.07.009

Eubanks Jr, T.L., Stoll, J.R. & Ditton, R.B. (2004). Understanding the diversity of eight birder sub-populations: socio-demographic characteristics, motivations, expenditures and net benefits. Journal of Ecotourism, 3(3), 151-172. doi:10.1080/14664200508668430 [ Links ]

Green, R. J., & Jones, D. N. (2010). Practices, needs and attitudes of birdwatching tourists in Australia. Queensland: Cooperative Research Center for Sustainable Tourism. [ Links ]

Guimarães, M. H., Nunes, L. C., Madureira, L., Santos, J. L., Boski, T. & Dentinho, T. (2014). Measuring birdwatchers’ preferences: A case for using online networks and mixed-mode surveys. Tourism Management, 46, 102-113. Doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2014.06.016

ICNF – Instituto de Conservação da Natureza e Florestas (2015). Parque Natural da Ria Formosa: Classificação | Caracterização. Retrieved from ICNF website: http://www.icnf.pt/portal/ap/p-nat/pnrf/class-carac [ Links ]

Jackson, S. (2007). Attitudes towards the environment and ecotourism of stakeholders in the UK tourism industry with particular reference to ornithological tour operators. Journal of Ecotourism, 6(1), 34-66. doi:10.2167/joe126.0 [ Links ]

Jafari, J. (2003). Encyclopedia of tourism. New York. Routledge. [ Links ]

Jones, D. N. & Buckley, R. (2001). Birdwatching Tourism in Australia. (Wildlife Tourism Research Report Series nº 10). Queensland: Cooperative Research Center for Sustainable Tourism. [ Links ]

Lee, C., Lee, Jin-Hyung, K., Tae-Kyun & Mjelde, J.W. (2010). Preferences and willingness to pay for birdwatching tour and interpretative services using a choice experiment. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(5), 695- 708. Doi:10.1080/09669581003602333

Machado, A. (2011). Bird-watching Tourism in Europe: case study of the Algarve. (Unpublished Master’s Thesis). Bournemouth University, United Kingdom

Ministério do Plano e da Administração do Território (1987). Decreto Lei 373/87, de 9 de Dezembro. Retrieved from Diário da República website: http://dre.tretas.org/dre/44878/. [ Links ]

Ministro, J. S. & Miguel, S. (2009). Birdwatching no Algarve – Propostas de Estruturação e Organização. Faro. Entidade Regional de Turismo do Algarve. [ Links ]

Mogollón, J.M.H., Cerro, A. M. C. & Durán, J.M.G. (2011). Propuestas para el desarrollo y comercialización del turismo ornitológico en Extremadura. Cuaderno de Turismo, 28, 93-119. Retrieved from: http://revistas.um.es/turismo/article/view/147241/131411 [ Links ]

Moore, R. L., Scott, D., & Moore, A. (2008). Gender-Based Differences in Birdwachters’ Participation and Commitment. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 13(2), 89-101. Doi:10.1080/10871200701882525

Newton, A. & Mudge, S.M. (2003). Temperature and salinity regimes in a shallow, mesotidal lagoon, the Ria Formosa, Portugal. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 57(1-2), 73–85. doi:10.1016/S0272- 7714(02)00332-3

Reynolds, P. C., & Braithwaite, D. (2001). Towards a conceptual framework for wildlife tourism. Tourism Management, 22(1), 31-42. doi:10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00018-2 [ Links ]

Ribeiro, J., Monteiro, C.C., Monteiro, P., Bentes, L., Coelho, R., Gonçalves, J. M.S., Lino, P.G., & Erzini, K. (2008). Long-term changes in fish communities of the Ria Formosa coastal lagoon (southern Portugal) based on two studies made 20 years apart. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 76(1), 57-68. Doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2007.06.001 [ Links ]

Roig, J. L. (2008). El turismo ornitológico en el marco del postfordismo, una aproximación Teórico-Conceptual. Cuadernos del Turismo, 21, 85-111. Retrieved from: http://revistas.um.es/turismo/article/view/25001 [ Links ]

Scott, D. & Thigpen, J. (2003). Understanding the birder as tourist: segmenting visitors to the texas hummer/bird celebration. Human Dimensions of Wildlife: An International Journal, 8(3), 199-218. Doi: 10.1080/10871200390215579 [ Links ]

Sociedade Polis Litoral, SA (2010). Avaliação Ambiental do Plano Estratégico da Intervenção de Requalificação e Valorização da Ria Formosa: Relatório Ambiental Final. Volume 1. Lisboas: Nemus – Gestão e Requalificação Ambiental, Lda

Tisdell, C. A. & Wilson, C. (2004). Economic, wildlife tourism and conservation: three case studies. Queensland: Cooperative Reserach Center for Sustainable Tourism [ Links ]

Turismo de Portugal (2006). Turismo de Natureza. 10 Produtos estratégicos para o desenvolvimento do turismo em Portugal. Lisboa: Ministério da Economia e da Inovação. [ Links ]

Turismo do Algarve (2012). Birdwatching Guide to the Algarve. Faro: Gráfica Comercial. [ Links ]

Vowles, G. A. & Vowles, R. S. (1994). Breeding Birds of the Algarve. Vila Real de Santo António: Centro de Estudos Ornitológicos no Algarve. [ Links ]

Wright, J. (1995). Birders and twitchers: Towards developing typologies. Tourism and Leisure: Towards the Millennium. Eastbourne: Leisure Studies Association. [ Links ]

Received: 15 July 2017

Revisions required: 25 November 2017

Accepted: 18 January 2018