Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.14 no.3 Faro set. 2018

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2018.14304

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Positive psychology and tourism: a systematic literature review

Psicologia positiva e turismo: uma revisão sistemática da literatura

Soraia Garcês1, Margarida Pocinho2, Saul Neves Jesus3, Michael Stephen Rieber4

1University of Madeira, Portugal, soraiagarces@gmail.com

2University of Madeira, Portugal, mpocinho@uma.pt

3University of Algarve, Portugal, snjesus@ualg.pt

4University of Algarve, Portugal, rieber.michael@yahoo.com

ABSTRACT

This study aims to outline the relationship between Positive Psychology and tourism through a systematic literature review. Tourism seeks to increase the wellbeing of people, and wellbeing is a crucial variable in Positive Psychology which in turn aims to understand and promote people’s potential. This research used as search terms ‘Positive Psychology’, ‘wellbeing’, ‘happiness’, ‘tourism’, ‘visitor’ and ‘travel’, terms which were applied through the Online Knowledge Library. The inclusion/exclusion criteria led to a sample of 49 references which were then individually analyzed. Results showed a recent increase in studies focused on the relationship between the variables, Europe being in the lead. Overall, policies are important for tourism development; tourism promotes wellbeing for residents and tourists; entrepreneurs have an innovative opportunity in wellbeing; and nature is linked to wellbeing. Implications and suggestions for future studies are presented.

Keywords: Positive psychology, tourism, wellbeing, nature, innovation.

RESUMO

Este estudo objetiva desenvolver uma visão geral sobre a aplicação da Psicologia Positiva no Turismo. O Turismo procura contribuir para aumentar o bem-estar das pessoas e o bem-estar é uma variável fundamental da Psicologia Positiva que procura compreender e promover o potencial dos indivíduos. Utilizou-se como termos de pesquisa as palavras ‘Psicologia Positiva’, ‘bem-estar’, ‘felicidade’, ‘turismo’, ‘visitante’ e ‘viagem’. A pesquisa foi realizada por meio da Biblioteca do Conhecimento Online. A aplicação de critérios de inclusão/exclusão levou a uma amostra final de 49 referências, analisadas individualmente. Os resultados mostram um interesse recente no estudo da relação em análise, sendo a Europa líder. Globalmente, a política é importante para o desenvolvimento do turismo; o turismo promove o bem-estar dos residentes e turistas; os empresários têm no bem-estar uma oportunidade de inovação; e a natureza relaciona-se com o bem-estar. Implicações e sugestões de estudos futuros são apresentadas.

Palavras-chave: Psicologia positiva, turismo, bem-estar, natureza, inovação.

1. Introduction

Following World Word II, Psychology has concentrated on how to heal wounds with a major emphasis on pathology instead of aiming at helping people flourish (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000; Seligman, Parks & Steen, 2004). In a special issue of American Psychologist, Positive Psychology emerges as a new movement. It started with Seligman (Scorsolini-Comin & Santos, 2010) and focused on prevention rather than only alleviating suffering. Subjective wellbeing and life satisfaction started to build the foundations for Positive Psychology (Teschers, 2015). Seligman (2013, p. 2) stated that “Positive Psychology is the scientific study of the strengths, characteristics, and actions that enable individuals and communities to thrive”.

Emerging as a science of happiness, Positive Psychology, as a movement, has been shifting towards wellbeing (Scorsolini- Comin, Fontaine, Koller, & Santos, 2013). Seligman (2010) proposed wellbeing as its new aim and expanded the prior elements of happiness to: a) positive emotion; b) engagement;

c) relationships; d) meaning and; e) accomplishment. These elements constitute wellbeing and are known as PERMA (Seligman, 2010). Fulmer (2015) describing it acknowledges that: a) positive emotion refers to happiness and life satisfaction; b) engagement can be related to Csikszentmihalyi ‘flow’ concept, and refers to the deep involvement in a given activity; c) meaning is connected to looking for something more than the person in himself/herself; d) relationships are linked to the fact that we are social beings, good relationships are therefore fundamental to our wellbeing; and, finally e) accomplishment is, rather an individual element, linked to the search of achieving something in life.

Philosophical tradition differentiated two types of happiness: a) subjective wellbeing (hedonia); and b) psychological wellbeing (eudaimonia) (Liu, 2013). Liu (2013) addressed subjective wellbeing as managing happiness, and psychological wellbeing as associated with people’s potential. Despite this differentiation, the wellbeing concept is usually characterized in terms of happiness (McCabe & Johnson, 2013). Nevertheless, wellbeing is a multidimensional construct and happiness is just one component (Seligman, 2013). The PERMA theory clearly illustrates this multidimensionality (Seligman, 2013).

Currently, research focused on human flourishing is allowing for the emergence of different directions in a specific field, namely tourism. Investigations surrounding tourist’s learning, relationships and even empathy regarding host communities are already being conducted (Pearce & Packer, 2013).

According to the International Recommendations for Tourism Statistics 2008 (Department of Economic and Social Affairs - Statistical Division [DESA], 2010) tourism is a social, cultural and economic occurrence that refers to the movement of people to somewhere different from their normal residence, with a crucial influence on the economy, environment, locals’ lives and the tourists themselves. DESA (2010) classifies tourism trips in two major categories: personal and professional. The personal includes: a) holiday; b) leisure and recreation; c) visiting friends and relatives; d) education and training; e) health and medical care; f) religion/pilgrimage; g) shopping; h) transit; and i) other.

The European Travel Commission [ETC] (2016) believes that in the near future travel and tourism business will be intensely affected by the tourist’s needs to better his/herself and to live a more fulfilled life. Tourism is a way to improve life (Filep & Pearce, 2014) and for Zhang (2013) it is an activity intimately connected to wellbeing, which in turn is the search for a greater quality of leisure life when people basic needs are fulfilled. The idea of traveling to relax and sunbath will still exist, but this new wave of travelers seeking new knowledge and activities cannot be left unattended, and therefore organizations should understand that the need for better and healthier lives will extend to people’s travel choices (ETC, 2016).

Tourist experience has been assumed as a practice of hedonic consumption. Happiness and wellbeing are often portrayed as pleasure resulting from touristic actions, and a lot of investigations are dedicated to the consequents of tourists’ hedonic wellbeing. However, we are currently in the rise of a new idea of ‘experience economy’, focused on individual development and self-realization. This new attitude induces the need for a more eudemonic approach to tourism where human flourishing is central. Despite that, research concentrating on eudaimonia is not the norm, and a new way to develop information of consumption in tourism is necessary and important to align theory and practice with the framework of this new experience economy (Kirillova, Lehto & Cai, 2016).

A proposed framework for tourist happiness was developed by Filep and Deery (2010). Having Seligman’s theory as a support, the researchers advocated that tourist happiness “is a state when a tourist experiences positive emotions (such as love, interest, joy, contentment), a sense of engagement in an activity (like flow or mindfulness) and derives meaning from tourist activities (or a sense of greater purpose)” (Filep, 2016, p. 1). The happiness model for tourist satisfaction is associated with the ‘quality of life’ construct and tourism can be seen as a significant element to promote quality of life of the tourists (Filep, 2008). Uysal, Sirgy, Woo and Kim (2015) explained that researchers tend to use ‘quality of life’ and ‘wellbeing’ indifferently, and tourists’ quality of life is influenced by touristic activities and experiences. Overall, research (Uysal et al., 2015) leads us to believe that tourism influences the tourists’ quality of life, generating a positive effect on leisure, social, family, work, spiritual, culinary, marital, cultural and many more aspects.

Individual wellbeing benefits derived from tourism experiences overlap with PERMA in the following terms: a) increase in pleasure (positive emotions); b) a sense of a deep involvement leading to skills development (engagement); c) development of relationships (positive relationships); d) individual growth (meaning) and; e) greater health (achievement). In the achievement facet, Filep (2014a) addressed three major results:

a) stress decrease; b) improved sleep and; c) cardiovascular health. It is not stated that tourist fulfilment matches PERMA in all its complexity, notwithstanding that the attempt made to link the research topics to the model was based on scientific results (Filep & Pearce, 2013).

Studies correlating tourism and happiness or wellbeing are uncommon and the majority are focused on residents’ happiness or on an economic viewpoint. Research concerning tourists’ wellbeing solely from their perspective is still lacking (Zhang, 2013).

Wellbeing is potentially a strong marketing instrument affecting consumer decision (Pyke, Hartwell, Blake & Hemingway, 2016). If a good strategy is put in place and if consumers start to understand the significance of a healthy lifestyle, there will be more motivation to travel to destinations that promote positive outcomes for people’s wellbeing (Pyke et al., 2016). Studies focused on authenticity, self-identify, spirituality, learning and much more, are emerging. This multiplicity is leading to an enrichment of the field, but it also shows that a clear direction does not exist (Bosangit, Hibbert & McCabe, 2015).

A well-conceived travel experience is crucial for the development of a sustainable tourism strategy (Coghlan, 2015). Tourism can gain a lot from social sciences’ endeavors (Bramwell, 2015). Researchers are now considering that there is a merging between Positive Psychology and Tourism Psychology that can lead to the development of positive changes and enhance psychological wellbeing. Our goal with this systematic literature review is to develop an overview of the relationship between Positive Psychology and Tourism, and its application in the sector.

2. MethodologyFollowing the PRISMA (2009) method, we selected as search terms: ‘Positive Psychology’, ‘Happiness’ and ‘Wellbeing’, for Positive Psychology and ‘Tourism’, ‘Visitor’ and ‘Travel’, for Tourism. The research took place during June and July 2017, through the use of B-On (Online Knowledge Library). Science Direct, SCOPUS, Social Sciences Citation Index and Science Citation Index databases were chosen, and the search focused on publications from 2007 to 2017 in English.

The inclusion criteria defined was: a) studies where one of the search terms from ‘Positive Psychology’ and ‘Tourism’ were present in the publication title; b) peer reviewed publications;

c) studies where the search terms were the main variables being studied; d) studies whose participants were above 18 years of age; and e) studies, theoretical and/or empirical, with validated methods and procedures. The exclusion criteria used was: a) studies where only one search term was present in the publication title; b) publications lacking peer review; c) studies where the search terms were not the main variables being studied; d) studies whose participants were under 18 years and

e) studies, theoretical and/or empirical, with non-validated methods and procedures.

ProcedureFirst, we crossed the search terms on B-On and used its navigation features. The Boolean operator ‘AND’ was used between terms, ensuring both were included in the search. In all crossings, the truncation symbol ‘*’ was used allowing the inclusion of words with the same origin. With the terms ‘visitor’ and ‘travel’ we added the truncation symbol ‘?’ to find their singular and plural forms. To include the search for written variations of ‘wellbeing’ (well-being, wellbeing and well being), Boolean operator ‘OR’ was used. For the keyword ‘Positive Psychology’ we used quotation marks to restrict findings to the exact term. The crossings were: ‘Happiness’ and ‘Tourism’; ‘Happiness’ and ‘Visitor’; ‘Happiness’ and ‘Travel’; ‘Wellbeing’ and ‘Tourism’; ‘Wellbeing’ and ‘Visitor’; ‘Wellbeing’ and ‘Travel’; ‘Positive Psychology’ and ‘Tourism’; ‘Positive Psychology’ and ‘Visitor’; ‘Positive Psychology’ and ‘Travel’.

To obtain the final sample, four main steps were required. First, an initial analysis with the chosen keywords, databases, dates and language was developed. Secondly, through the B-On search features inclusion criteria a) and b) were applied. Thirdly, results were imported to EndNote and an analysis of repeated measures fulfilled. Furthermore, a manual review was also conducted. Finally, the remaining inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied through careful revision of each title and abstract. During this step, particular attention was given to the aim, goal, and content of each study in order to decide the final sample.

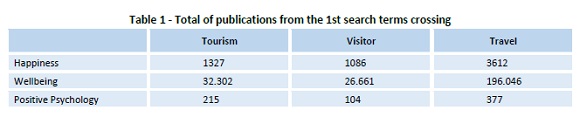

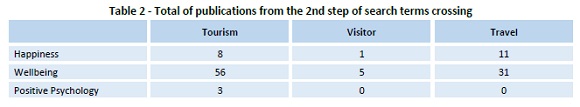

3. Results and discussionA total of 261.730 references were found in the first step of the search (Table 1). Through the application of the inclusion criteria a) and b) this number decreased to 115 publications (Table 2). Since in this step restrictions more aligned with our study goal were applied, it revealed, in our understanding, a closer look to the publications being developed in the confluence between (Positive) Psychology and Tourism.

The 115 references were imported to EndNote. Nine duplicates were found and manually four more. All were withdrawn. The remaining inclusion/exclusion criteria led to the exclusion of 53 references: eight did not have one of the search terms in the title; one addressed participants less than 18 years old; five were duplicates with written errors in the title or authors’ name hence not previously found; five were commentaries or book reviews that were not deemed pertinent to the study, since one was a research probe, two were book summaries, one a short commentary and one a meeting abstract; and 34 did not address the key terms as main variables and/or these were secondary to the main goal of the publications (for example, some addressed daily travel that was not relevant to our study). Our final sample consequently consisted of 49 references.

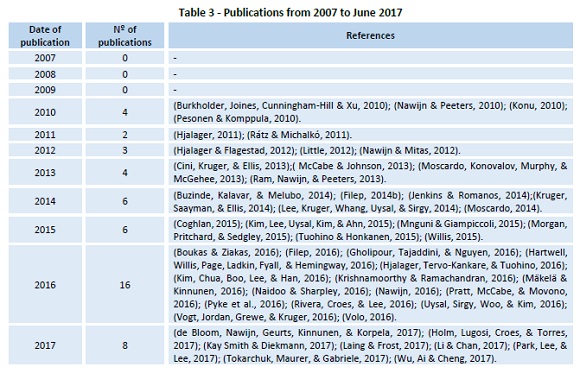

Key topics and publications conclusions were observed carefully. In a first overview, we could see (Table 3) that from 2007 until 2009 we did not find publications that comply with the chosen criteria. The first references come in 2010 and are scarce until 2015. In 2016 the references double when compared with 2015, and in 2017 (at the date of this research) we already had a number of references that lead us to believe that a similar number of references from 2016 may be, eventually, achieved at the end of this year. This result may reflect that applying Positive Psychology to the Tourism settings is rather new and in the process of interesting more researchers to its potential. This is in accordance with Zhang (2013), who acknowledges that studies that link tourism and wellbeing are not the norm.

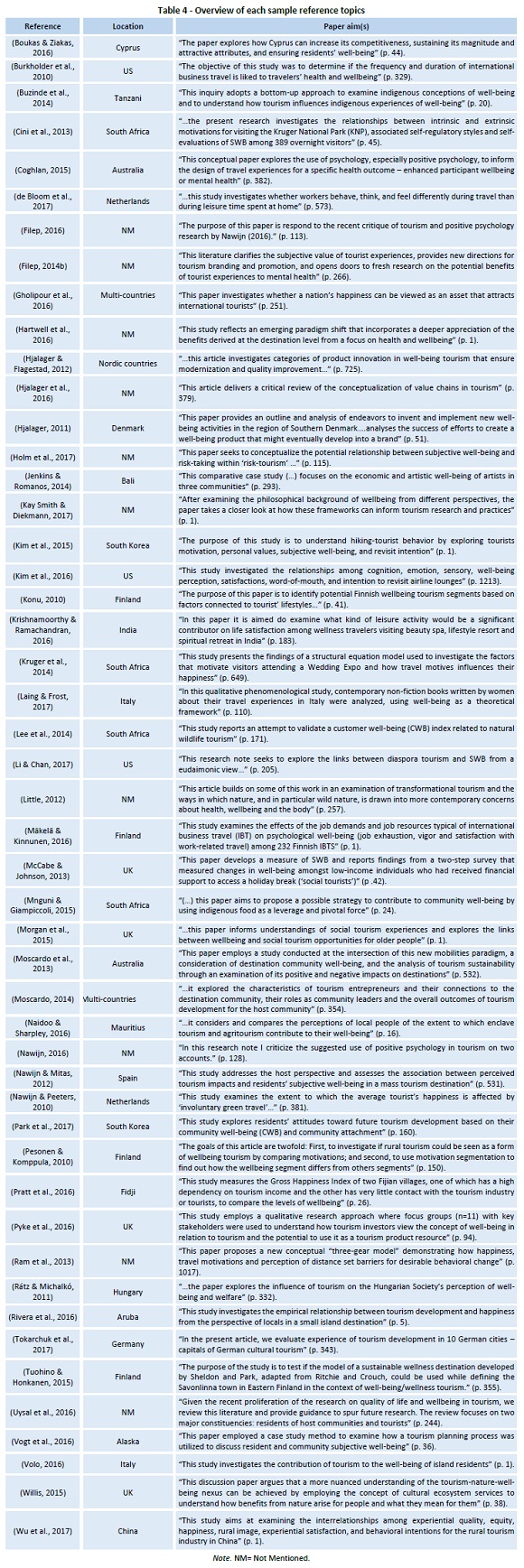

In Table 4 the location where the study was conducted is identified and/or where the participants were from. The overall aim of each publication is also stated. The majority of studies are being developed in Europe with particular emphasis in the Nordic countries (Hjalager, 2011; Hjalager & Flagestad, 2012; Konu, 2010; Mäkelä & Kinnunen, 2016; Pesonen & Komppula, 2010; Tuohino & Honkanen, 2015) and the UK (McCabe & Johnson, 2013; Morgan et al., 2015; Pyke et al., 2016; Willis, 2015). Furthermore, a dispersion of the remaining publications is observable in Europe through different countries such as Netherlands (de Bloom et al., 2017; Nawijn & Peeters, 2010); Hungary (Rátz & Michalkó, 2011), Spain (Nawijn & Mitas, 2012), Italy (Laing & Frost, 2017; Volo, 2016), Germany (Tokarchuk et al., 2017) and Cyprus (Boukas & Ziakas, 2016). It is interesting to note that the Nordic countries are in the lead. It is well known that these countries are known to be the “happiest” ones’. Nordic countries have in common a high appreciation for equality, inclusion, and care of their people (Jackson, 2017), which means that they already go beyond the fulfillment of basic needs with higher aims. According to Zhang (2013), when our basic needs are satisfied we tend to search for the next step and improve our quality of life, and tourism is a form to better our life (Filep & Pearce, 2014).

Following the studies’ results, we found that policies are a concern for many tourism actors. Boukas and Ziakas (2016) concluded that in Cyprus there is a need to rethink policies so that they acknowledge community wellbeing directly. Nawijn and Peeters (2010) concluded that the freedom to choose a destination is the biggest factor for tourist happiness. Consequently, policies that restrict this aspect will have a negative impact. Mnguni and Giampiccoli (2015) proposed the development of a teaching and learning centre for indigenous and cultural tourism as a potential form to promote community wellbeing and tourism development, reinforcing the importance of the involvement of policies. Vogt et al. (2016) in a case study exploring how a tourism planning process was used to debate locals wellbeing discovered that those who took part in the study were usually more active, thoughtful, curious and looking forward to using their abilities for the community. They concentrated on the protection of wellbeing but also explored directions for tourism development. The study suggested that residents’ ideas and concerns should be requested when developing tourism projects. Buzinde et al. (2014) concluded that tourism has both positive and negative results in community wellbeing. That is, it is important to consider residents wellbeing and their engagement in policies making. Park et al. (2017) found that, for community wellbeing, income is the most powerful factor and safety service for community attachment. Community wellbeing affects community attachment and locals’ attitudes. These findings may be helpful in the development of policies that promote locals’ positive attitudes towards tourism development.

Another result showed that usually tourism has positive outcomes in people’s wellbeing. Nawijn and Mitas (2012) concluded that tourism influences in a positive manner locals’ health and interpersonal relationships. Volo (2016) found that the contact of locals with tourists can increase their eudaimonic wellbeing. Uysal et al. (2016) concluded that tourists’ experiences impacts their life satisfaction, locals’ wellbeing and positively influence a diversity of life aspects such as family, social relations, leisure, culture and much more. Kim et al. (2016) concluded that perceptions of wellbeing from travelers in airlines lounge areas led to higher levels of satisfaction. Moscardo et al. (2013), focusing their research on mobility patterns, discovered that tourists who embarked in slower, repeated and longer movement over a region, and had higher engagement with the location were linked to higher destinations’ wellbeing. Tokarchuk et al. (2017) found out that the increase of tourists per local influences significantly and positively residents wellbeing. Nevertheless, this increase must be at a slow pace, as Moscardo et al. (2013) found, since a fast rise in tourists’ arrivals induces smaller growths in locals’ wellbeing. Jenkins and Romanos (2014) concluded that it is possible to develop local artists’ wellbeing in tourism sets. McCabe and Johnson (2013) also found out that tourism promotes social tourists wellbeing, and likewise Morgan et al. (2015) determined that social tourism can positively impact older people’s subjective wellbeing. Rivera et al. (2016) also found that, from locals’ viewpoints, tourism and happiness have a positive association. Ram et al. (2013) concluded that happiness is crucial in all the steps of tourists’ experiences. Likewise, the results from Wu et al. (2017) back up the idea that happiness is fundamental in enhancing tourists’ behavioral intentions. Gholipour et al. (2016) study outcomes suggested that international tourists have a preference to travel to places that show higher happiness. Overall, researchers seem to acknowledge that tourism indeed promotes happiness and wellbeing both for residents and for tourists.

Results also indicate that wellbeing is a key feature of many studies, all contributing to support its importance for tourism. Coghlan (2015) concluded that Positive Psychology principles are a valuable tool to develop experiences for tourists that promote mental health, such as charity challenge events. Kruger et al. (2014) found that, in a particular setting of tourism event, it was the features of the event per se and the development of relationships that most increased the visitors’ life satisfaction and happiness. Filep (2014b) argued that to conceptualize tourist happiness in terms of subjective wellbeing is difficult since a) it is hard to explain meaningful holiday experiences through it and b) it cannot clearly explain people’s engagement with local experiences. For Filep (2014b) the authentic happiness model is more accurate to explain tourist happiness. In another study, Filep (2016) surmised that there is still space for more eudaimonic approaches. Nawijn (2016) concluded that tourists can experience meaningful activities that are not hedonic, and the influence of Positive Psychology in tourism wellbeing is less than what is largely stated. de Bloom et al. (2017) concluded that, when traveling, individuals showed higher levels of hedonic wellbeing and ruminative thinking was lower when compared to leisure time at home. Li and Chan (2017) found six dimensions by which diaspora tourism promotes tourists’ subjective wellbeing. Laing and Frost (2017) phenomenological study of travel experiences in Italy found also six wellbeing dimensions and hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing notions were found in the narratives. Konu (2010) found six segments of wellbeing tourism in Finland considering tourists’ lifestyles, with significant differences between segments regarding geo-demographic factors, traveling habits and interests in different activities. Kay Smith and Diekmann (2017) proposed a Model of Integrative Wellbeing Tourism Experiences. To optimize wellbeing tourism a combination of three dimensions (meaningful experiences; pleasure and hedonism; and altruistic activities and sustainability) is needed. These conclusions support the idea that many conceptualizations exist, but overall wellbeing is positively associated with tourism and concepts of hedonia and eudemonia are emerging. However, Naidoo and Sharpley (2016) found, in Mauritius, that enclave and agritourism have positive and negative impacts on the community wellbeing. Rátz and Michalkó (2011) also found that for Hungarians, tourism is not fundamental to their quality of life. Pratt et al. (2016) found, in Fidgi, that one village that is dependent on tourism has lower levels of happiness when compared to another village where tourism is almost non-existent. Burkholder et al. (2010) concluded that there is a positive but also a negative relationship between business travelers’ health risks and wellbeing. Mäkelä and Kinnunen (2016) examining international business travel and psychological wellbeing found that workload and work pressure are predictive of exhaustion. Human resources practices of support to these travelers were predictive of vigor and satisfaction in work travel. In risk- tourism, Holm et al. (2017) noted that the literature suggests that people that are risk inclined may benefit from higher levels of subjective wellbeing when partaking in risk experiences. The researchers found that ‘emotion’ is a common attribute between risk-taking tourism and subjective wellbeing. The existing literature has associated risk with happiness - however, merely considering positive emotions and “forgetting” the negative ones. For this reason, it is suggested that future studies consider negative emotions and how they can add to individuals’ subjective wellbeing. The outcomes of these studies show that positive and negative features in wellbeing can be found in tourism settings and that there is still space for more exploration. However, it is clear that more positive outcomes than negatives were acknowledged, although we do believe that it is important to consider contexts and each result as full of information that can help in future studies development.

Another conclusion is a concern with the need to reinvent the tourism industry while still acknowledging the happiness, satisfaction, and wellbeing of its actors. Pyke et al. (2016) concluded that wellbeing as a business tool has the possibility to increase the destinations’ economies, and entrepreneurs are eager to use its potential as a new product offer. Hartwell et al. (2016) acknowledged a shift from wellbeing in tourism focused on products, motivations, and attitudes to a more profound in- depth understating of its benefits for tourists and for locals. These ideas are being associated to Positive Psychology and to how tourism experiences can contribute to human flourishing. The review of Hartwell et al. (2016) reflected that this new conceptualization can be a novel way to promote destinations using wellbeing as a marketing tool. Moscardo (2014) found that the community entrepreneurs showed higher success in promoting positive outcomes for tourism and for locals. Additionally, they concluded that financial and built/physical capital were less important than social and human resources for the development of the community and that administration structures are fundamental for the sustainability of tourism development. Lee et al. (2014) concluded that to promote positive behavior from visitors they should develop wellbeing through satisfaction growth. Another study (Cini et al., 2013) concluded that tourists that are more intrinsically motivated show higher degrees of life satisfaction and positive feelings. Kim et al. (2015) concluded that the intention to revisit a destination is influenced by the tourist motivation and subjective wellbeing and that motivations and personal values in hiking-tourists are predictive of subjective wellbeing. Hjalager et al. (2016) concluded that rural wellbeing tourism can benefit from two approaches: a) a destination logic, which addresses the consumption steps and processes related to the needs for products and services, and b) a supply chain logic, which takes into account the wider contributions to the composition of products and services across business sectors. However, local rural areas may gain more if they focus on the latter. Hjalager (2011) determined that it is possible to generate new products and services regarding the development of a wellbeing tourism region and highlighted the importance of intersectorial cooperation. However, it is not without difficulties. Tuohino and Honkanen’s (2015) research in Savonllinna concluded that, in practical terms, the region was not yet a sustainable wellbeing tourism destination and the idea of a wellbeing segment was still limited. Hjalager and Flagestad (2012) acknowledged that there still exists room for innovation and development in wellbeing tourism and entrepreneurs are willing to give it a try. These results show a concern with the promotion and care of tourists and also that motivation and satisfaction are important for revisit intention, while also reinforcing the need for innovation.

A particularly interesting result is an apparent relationship between nature and wellbeing. Willis (2015) argued that psychological wellbeing gains obtained from interactions with nature can lead to a deeper comprehension of cultural ecosystems services. Little (2012) discovered that the most direct form in which nature is connected with health and wellbeing is the location choice for holidays. Notions of health and a fit body molds tourism behavior and nature tourism activities allow for therapeutic practices in the search for wellbeing. Pesonen and Komppula (2010) found out that in Finland’s rural tourism it is possible to differentiate a particular segment, where people search for relaxation and escape from daily life stress. It is concluded that leisurely rural contexts surrounded by nature and wonderful views provide the perfect environment for wellbeing holidays that have relaxation, comfort, and escape as principal motives to embark in these tourism experiences. Krishnamoorthy and Ramachandran (2016) found that: there is a relationship between wellness and health lifestyles and life satisfaction; overall wellness activities are important for life satisfaction; a planned dietary activity was more conductive to life satisfaction than travel behavior and leisure activities. This last one was negatively associated with life satisfaction. These conclusions allow us insight into nature as a privileged context for tourism related to wellbeing, and therefore emphasizing its potential for exploration by tourism actors.

4. Conclusion

This systematic literature review allowed for an overview of the relationship between Positive Psychology and Tourism. Only in the last year and a half, this relationship is being taken more into consideration by researchers. Europe is in the lead, in particular, the Nordic countries. Overall, the topics addressed vary to a great extent, which again emphasizes the vast array of ideas and constructs being studied (Bosangit et al., 2015). A key point of this research is that policy is a concern for tourism actors. Additionally, wellbeing is positively linked to tourism experiences, from both residents’ and tourists’ perspectives. An interesting association between nature and wellbeing was noted, although further studies to explore this relationship are required. Also, a concern with tourism development with wellbeing as a center piece is expressed by entrepreneurs, who have the chance to transform wellbeing into a product and a marketing strategy, constituting an innovative tool for the promotion of destinations. The existing views imply a holistic perspective to fully understand how tourism is affecting wellbeing, where locals, tourists and entrepreneurs’ inputs are taken into consideration.

Although this study has limitations, we provide suggestions for improvement. The criteria used may have limited the research. Despite our efforts to conduct an objective analysis, there is undoubtedly an amount of subjective reflections that could be improved by inter-observer agreement reliability. Moreover, in further studies we want to go beyond hedonic and eudaimonic views and investigate personal characteristics of locals and/or tourists. Particular interest and potential are seen in the study of creativity, spirituality, and optimism since these are fundamental for more positive fulfilling lives. They add meaning, engagement, and positive emotions, improving relationships and achievements in people lives, through creative and meaningful endeavors with positive outcomes.

REFERENCES

Bosangit, C., Hibbert, S., & McCabe, S. (2015). If I was going to die I should at elast be having fun: Travel blogs, meaning and tourist experience. Annals of Tourism Research, 55, 1-14. DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2015.08.001. [ Links ]

Boukas, N. & Ziakas, V. (2016). Research paper: Tourism policy and residents’ well-being in Cyprus: Opportunities and challenges for developing an inside-out destination management approach. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5(1), 44-54. DOI: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.12.004.

Bramwell, B. (2015). Theoretical activity in sustainable tourism research. Annals of Tourism Research, 54, 204-218. DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2015.07.005. [ Links ]

Burkholder, J. D., Joines, R., Cunningham-Hill, M., & Xu, B. (2010). Health and well-being factors associated with international business travel. Journal of Travel Medicine, 17(5), 329-333. DOI: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2010.00441.x. [ Links ]

Buzinde, C. N., Kalavar, J. M. & Melubo, K. (2014). Tourism and community well-being: The case of the Maasai in Tanzania. Annals of Tourism Research, 44, 20-35. DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2013.08.010. [ Links ]

Cini, F., Kruger, S. & Ellis, S. (2013). A model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations on subjective well-being: The experience of overnight visitors to a National Park. Applied Research Quality Life, 8(1), 45-61. DOI: 10.1007/s11482-012-9173-y. [ Links ]

Coghlan, A. (2015). Tourism and health: Using positive psychology principles to maximise participants’ wellbeing outcomes - A design concept for charity challenge tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(3), 382-400. DOI: 10.1080/09669582.2014.986489.

de Bloom, J., Nawijn, J., Geurts, S., Kinnunen, U., & Korpela, K. (2017). Holiday travel, staycations, and subjective well-being. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(4), 573- 588. DOI: 10.1080/09669582.2016.1229323. [ Links ]

Department of Economic and Social Affairs - Statistics Division (2010). International Recommendations for Tourism Statistics 2008. New York: United Nations Publication. [ Links ]

European Travel Commission (2016). Lifestyle trends & Tourism: How changing consumer behavior impacts travel to Europe. Brussels: European Travel Commission. [ Links ]

Filep, S. (2014a). Consider prescribing tourism. Journal of Travel Medicine, 21(3), 150-152. DOI: 10.1111/jtm.12104.

Filep, S. (2014b). Moving beyond subjective well-being: A tourism critique. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 38(2), 266-274. DOI: 10.1177/1096348012436609.

Filep, S. (2016). Tourism and positive psychology critique: Too emotional? Annals of Tourism Research. Advanced online publication. DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2016.04.004. [ Links ]

Filep, S. (2008, June). Linking tourist satisfaction to happiness and quality of life. Paper presented at the 8th BEST EN think tank on Sustaining quality of life through tourism, [ Links ] Izmir University of Economics, Turkey.

Filep, S. & Deery, M. (2010). Towards a picture of tourists’ happiness. Tourism Analysis, 5, 399-410. DOI: 10.3727/108354210X12864727453061.

Filep, S. & Pearce, P. (2013). A blueprint for tourist experience and fulfilment research. In P. Pearce & S. Filep (Eds.), Tourist experience and fulfilment: insights from positive psychology (pp. 223-232). New York, NY: Routledge.

Filep, S. & Pearce, P. (2014). Tourist experience and fulfilment: Insights from positive psychology. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Fulmer, R. (2015). A history of happiness: The roots of positive psychology, insight, and clinical applications from 2005 to 2015. Retrieved from http://www.counseling.org/docs/defaultsource/vistas/article_45a15c21f16116603abcacff0000bee5e7.pdf?sfvrsn=6 [ Links ]

Gholipour, H. F., Tajaddini, R. & Nguyen, J. (2016). Happiness and inbound tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 57, 251-253. DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2015.12.003. [ Links ]

Hartwell, H., Willis, C., Page, S., Ladkin, A., Fyall, A., & Hemingway, A. (2016). Progress in tourism and destination wellbeing research. Current Issues in Tourism. Advanced online publication. DOI: 10.1080/13683500.2016.1223609. [ Links ]

Hjalager, A. M. (2011). The invention of a Danish Well-being Tourism Region: Strategy, substance, structure, and symbolic action. Tourism Planning & Development, 8(1), 51-67. DOI: 10.1080/21568316.2011.554044. [ Links ]

Hjalager, A. M., Tervo-Kankare, K. & Tuohino, A. (2016). Tourism value chains revisited and applied to rural well-being tourism. Tourism Planning & Development, 13(4), 379-395. DOI: 10.1080/21568316.2015.1133449. [ Links ]

Hjalager, A. M. & Flagestad, A. (2012). Innovations in well-being tourism in the Nordic countries. Current Issues in Tourism, 15(8), 725-740. DOI: 10.1080/13683500.2011.629720. [ Links ]

Holm, M. R., Lugosi, P., Croes, R. R., & Torres, E. N. (2017). Progress in tourism management: Risk-tourism, risk-taking and subjective well- being: A review and synthesis. Tourism Management, 63, 115-122. DOI: 10.1016/j.tourman.2017.06.004. [ Links ]

Jackson, S. (2017). Why Nordic countries top the happiness league. Retrieved from https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/why-nordic-countries-top-the-happiness-league [ Links ]

Jenkins, L. D. & Romanos, M. (2014). The art of tourism-driven development: economic and artistic well-being of artists in three Balinese communities. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 12(4), 293-306. DOI: 10.1080/14766825.2014.934377. [ Links ]

Kay Smith, M. & Diekmann, A. (2017). Tourism and wellbeing. Annals of Tourism Research, 66, 1-13. DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2017.05.006. [ Links ]

Kim, H. C., Chua, B. L., Boo, H. C., Lee, S., & Han, H. (2016). Understanding airline travelers’ perceptions of well-being: The role of cognition, emotion, and sensory experiences in airline lounges. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 33(9), 1213-1234.DOI: 10.1080/10548408.2015.1094003.

Kim, H., Lee, S., Uysal, M., Kim, J., & Ahn, K. (2015). Nature-based tourism: Motivation and subjective Well-Being. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 32, 1-21. DOI: 10.1080/10548408.2014.997958. [ Links ]

Kirillova, K., Lehto, X., & Cai, L. (2016). Existential authenticity and anxiety as outcomes: The tourist in the experience economy. International Journal of Tourism Research, 19 (1), 13-26. DOI: 10.1002/jtr.2080. [ Links ]

Konu, H. (2010). Identifying potential wellbeing tourism segments in Finland, Tourism Review, 65(2), 41-51. DOI: 10.1108/16605371011061615. [ Links ]

Krishnamoorthy, S. & Ramachandran, T. (2016). Wellness travel and happiness: An empirical study into the outcome of wellness activities on tourists’ subjective wellbeing. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Review and Research, 41(2), 183-187.

Lee, D. J., Kruger, S., Whang, M. J., Uysal, M., & Sirgy, M. J. (2014). Validating a customer well-being index related to natural wildlife tourism. Tourism Management, 45, 171-180. DOI: S0261517714000752. [ Links ]

Kruger, S., Saayman, M. & Ellis, S. (2014). The influence of travel motives on visitor happiness attending a wedding Expo. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 31(5), 649-665. DOI: 10.1080/10548408.2014.883955. [ Links ]

Laing, J. H. & Frost, W. (2017). Journeys of well-being: Women’s travel narratives of transformation and self-discovery in Italy. Tourism Management, 62, 110-119. DOI: 10.1016/j.tourman.2017.04.004.

Li, T. E. & Chan, E. T. H. (2017). Diaspora tourism and well-being: A eudaimonic view. Annals of Tourism Research, 63, 205-206. DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2017.01.005. [ Links ]

Liu, K. (2013). Happiness and tourism. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 4(15), 67-70. [ Links ]

Mäkelä, L. & Kinnunen, U. (2016). International business travelers’ psychological well-being: the role of supportive HR practices. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. Advanced online publication. DOI: 10.1080/09585192.2016.1194872.

McCabe, S. & Johnson, S. (2013). The happiness factor in tourism: Subjective well-being and social tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 41, 42-65. DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2012.12.001. [ Links ]

Mnguni, E. M. & Giampiccoli, A. (2015). Indigenous food and tourism for community well-being: A possible contributing way forward. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6(3), 24-34. DOI: 10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n3s2p24. [ Links ]

Morgan, N., Pritchard, A. & Sedgley, D. (2015). Social tourism and well- being in later life. Annals of Tourism Research, 52, 1-15. DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2015.02.015. [ Links ]

Moscardo, G. (2014). Tourism and community leadership in rural regions: Linking mobility, entrepreneurship, tourism development and community well-being. Tourism Planning & Development, 11(3), 354- 370. DOI: 10.1080/21568316.2014.890129. [ Links ]

Moscardo, G., Konovalov, E., Murphy, L., & McGehee, N. (2013). Mobilities, community well-being and sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(4), 532-556. DOI: 10.1080/09669582.2013.785556. [ Links ]

Naidoo, P. & Sharpley, R. (2016). Research paper: Local perceptions of the relative contributions of enclave tourism and agritourism to community well-being: The case of Mauritius. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5(1), 16-25. DOI: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.11.002. [ Links ]

Nawijn, J. (2016). Positive psychology in tourism: A critique. Annals of Tourism Research, 56, 128-163. DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2015.11.004. [ Links ]

Nawijn, J. & Mitas, O. (2012). Resident attitudes to tourism and their effect on subjective well-being: The case of Palma de Mallorca. Journal of Travel Research, 51(5), 531-541. DOI: 10.1177/0047287511426482. [ Links ]

Nawijn, J. & Peeters, P. (2010). Travelling ’green’: Is tourists’ happiness at stake? Current Issues in Tourism, 13(4), 381-392. DOI: 10.1080/13683500903215016.

Park, K., Lee, J., & Lee, T. J. (2017). Residents’ attitudes toward future tourism development in terms of community well-being and attachment. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 22(2), 160-172. DOI: 10.1080/10941665.2016.1208669.

Pearce, P.L. & Packer, J. (2013). Minds on the move: New links from psychology to tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 40, 386-411. DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2012.10.002. [ Links ]

Pesonen, J. & Komppula, R. (2010). Rural wellbeing tourism: Motivations and expectations. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 17, 150-157. [ Links ] DOI: 10.1375/jhtm.17.1.150.

Pratt, S., McCabe, S. & Movono, A. (2016). Gross happiness of a ’tourism’ village in Fiji. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5(1), 26-35. DOI: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.11.001.

PRISMA (2009). PRISMA flow diagram. Retrieved from http://www.prisma-statement.org/Default.aspx [ Links ]

Pyke, S., Hartwell, H., Blake, A., & Hemingway, A. (2016). Exploring well- being as a tourism product resource. Tourism Management, 55, 94-105. DOI: 10.1016/j.tourman.2016.02.004. [ Links ]

Ram, Y., Nawijn, J. & Peeters, P. M. (2013). Happiness and limits to sustainable tourism mobility: a new conceptual model. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(7), 1017-1035. DOI: 10.1080/09669582.2013.826233. [ Links ]

Rátz, T. & Michalkó, G. (2011). The contribution of tourism to well-being and welfare: The case of Hungary. International Journal of Sustainable Development, 14(3/4), 332-346. DOI: 10.1504/IJSD.2011.041968. [ Links ]

Rivera, M., Croes, R. & Lee, S. H. (2016). Research paper: Tourism development and happiness: A residents’ perspective. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5(1), 5-15. DOI: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.04.002.

Scorsolini-Comin, F. & Santos, M. (2010). Psicologia Positiva e os Instrumentos de Avaliação no Contexto Brasileiro. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 23(3), 440-448). DOI: 10.1590/S0102-79722010000300004. [ Links ]

Scorsolini-Comin, F., Fontaine, A., Koller, S., & Santos, M. (2013). From authentic happiness to well-being: The flourishing of positive psychology. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 26(4), 663-670. DOI: 10.1590/S0102-79722013000400006. [ Links ]

Seligman, M. (2010). Flourish: Positive psychology and positive interventions. Retrieved from http://tannerlectures.utah.edu/_documents/a-to-z/s/Seligman_10.pdf [ Links ]

Seligman, M. (2013). Building the state of wellbeing: A strategy for South Australia. Adelaide thinker in residence 2012-2013. Adelaide, SA Department of the Premier and Cabinea. [ Links ]

Seligman, M. & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5-14. DOI: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5. [ Links ]

Seligman, M., Parks, A. & Steen, T. (2004). A balanced psychology and a full life. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society London B., 359, 1379-1381. DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1513. [ Links ]

Seligman, M., Steen, T., Parks, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology in progress. Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60, 410-421. DOI: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410. [ Links ]

Teschers, C. (2015) The art of living and positive psychology in dialogue. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 47(9), 970-981. DOI: 10.1080/00131857.2015.1044839. [ Links ]

Tokarchuk, O., Maurer, O. & Gabriele, R. (2017). Development of city tourism and well-being of urban residents: A case of German Magic Cities. Tourism Economics, 23(2), 343-359. DOI: 10.1177/1354816616656272. [ Links ]

Tuohino, A. & Honkanen, A. (2015). On the way to sustainable (well- being) tourism destination? The case of Savonlinna town in Finland. Tourism Analysis, 20(4), 355-367. DOI: 10.3727/108354215X14400815080325. [ Links ]

Uysal, M., Sirgy, M. J., Woo, E., & Kim, H. (2016). Progress in tourism management: Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tourism Management, 53, 244-261. DOI: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.07.013. [ Links ]

Uysal, M., Siry, M., Woo, E., & Kin, H. (2015). Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tourism Management, 53, 244-261. DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.07.013. [ Links ]

Vogt, C., Jordan, E., Grewe, N., & Kruger, L. (2016). Collaborative tourism planning and subjective well-being in a small island destination. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 5(1), 36-43. DOI: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.11.008. [ Links ]

Volo, S. (2016). Eudaimonic well-being of islanders: Does tourism contribute? The case of the Aeolian Archipelago. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management. Advanced online publication. DOI: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2016.08.002. [ Links ]

Willis, C. (2015). The contribution of cultural ecosystem services to understanding the tourism-nature-wellbeing nexus. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 10, 38-43. DOI: 10.1016/j.jort.2015.06.002. [ Links ]

Wu, H., Ai, C. & Cheng, C. (2017). A study of experiential quality, equity, happiness, rural image, experiential satisfaction, and behavioral intentions for the rural tourism industry in China. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration. Advanced online publication. DOI: 10.1080/15256480.2017.1289138. [ Links ]

Zhang, T. (2013). The build of tourism well-being Index System. Business and Management Research, 2(4), 110-115. DOI: 10.5430/bmr.v2n4p110. [ Links ]

Acknowledgment

Special thanks to ARDITI - Agência Regional para o Desenvolvimento da Investigação Tecnologia e Inovação through the support provided under the Project M1420-09- 5369-FSE-000001 - Post Doctoral Research Grant.

Guest Editors:

· J. A. Campos-Soria

· J. Diéguez-Soto

· M. A. Fernández-Gámez

Received: 17.11.2017

Revisions required: 12.02.2018

Accepted: 21.05.2018