Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.14 no.3 Faro set. 2018

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2018.14305

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Economic and image impacts of summer Olympic games in tourist destinations: a literature review

Impactos econômicos e de imagem dos jogos Olímpicos de verão em destinos turísticos: uma revisão da literatura

Luciana Brandão Ferreira1,Marina Toledo de Arruda Lourenção2, Janaina de Moura Engracia Giraldi3, Jorge Henrique Caldeira de Oliveira4

1University of São Paulo, School of Economics, Business Administration and Accounting, 3900 Bandeirantes Avenue, 14040-905, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil, bfluciana@gmail.com

2University of São Paulo, School of Economics, Business Administration and Accounting, 3900 Bandeirantes Avenue, 14040-905, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil, malourencao@gmail.com

3University of São Paulo, School of Economics, Business Administration and Accounting, 3900 Bandeirantes Avenue, 14040-905, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil, jgiraldi@usp.br

4University of São Paulo, School of Economics, Business Administration and Accounting, 3900 Bandeirantes Avenue, 14040-905, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil, jorgecaldeira@usp.br

ABSTRACT

This article aims to verify in the literature related to the Summer Olympics the main economic and image implications for the destination hosting it. A qualitative exploratory research was carried out with the survey of scientific articles of the last twenty-five years in five different databases. The studies indicate economic and image gains and losses from hosting the games. As positive aspects, most of the studies mention those coming from Olympic spending that provided long-term gains for the resident population in the host locality and related to tourist activity. The most cited negative aspects are related to investments that generated benefits only in the short term or lack of investment in infrastructure. It is concluded that the preparation and implementation processes in each country are too different for the results to be uniform. In addition, the diverse methodological aspects of the articles also influence their results.

Keywords: Summer Olympic Games, economic impacts, tourist destination image.

RESUMO

Este artigo tem por objetivo verificar na literatura relacionada aos Jogos Olímpicos de Verão as principais implicações econômicas e de imagem para o destino que o hospeda. Realizou-se uma pesquisa exploratória qualitativa com levantamento de artigos científicos dos últimos vinte e cinco anos em cinco bases de dados diferentes. Os estudos encontrados indicam ganhos econômicos e de imagem, bem como perdas ao se realizar um megaevento esportivo. Como aspectos positivos, a maioria dos estudos menciona aqueles provenientes de investimentos olímpicos que proporcionaram ganhos a longo prazo para a população residente na localidade de acolhimento e relacionados com a atividade turística. Os aspectos negativos mais citados estão relacionados a investimentos que geraram benefícios apenas no curto prazo, ou falta de investimento em infraestrutura. Conclui-se que os processos de preparação e implementação em cada país são muito diferentes para que os resultados sejam uniformes. Além disso, os diversos aspectos metodológicos dos artigos também influenciam seus resultados.

Palavras-chave: Jogos Olímpicos de Verão, impactos econômicos, imagem de destino turístico.

1. Introduction

Studies on the impact of international mega-events in the host countries have been carried out, especially with regard to mega-sport events (Chen, 2012). The hosting of these events, by virtue of their size, bring changes to the country, either in more tangible aspects such as investments in infrastructure and works, or intangible aspects such as political and social climate, and image. In addition to issues related to infrastructure and economic development, a point cited in scientific articles on the subject is the image as a tourist destination of the site that hosts the mega-event (Knott, Fyall, & Jones, 2015; Deng & Li, 2013). There is a strategic leverage of images that are shown to the world in conjunction with the event (pre, during and after), and the level of awareness of a given city and/or country can be raised, which can boost tourist visitation at some point in the future, or at least be used to educate the world about a specific locality (Gibson, Qi & Zhang, 2008).

The objective of this article is to verify what are the main economic and destination image implications for the host city of a sports mega-event that have been described in the literature. For the survey, the Summer Olympic Games were chosen as they are considered the biggest sporting event in the world, including a series of sports, have a high media impact, and require a great investment. A qualitative exploratory research was carried out by means of mapping and analysis of articles in five databases that dealt with economic and image aspects for the host of the Summer Olympic Games of the last 25 years.

Mega-events are usually evaluated in terms of the economic impact of the event itself, with little focus given to the event as part of the larger process that can be investigated longitudinally (Hiller, 2006). Müller and Moesch (2010) argue that substantial economic effects can be expected from mega-events, especially with respect to tourism. Regarding the image, Getz (1993) emphasizes that mega-events generate much of the tourist demand and contribute to creating a positive image of the destination. A positive image of the destination may influence the intention to visit it as studies have indicated (Pike & Ryan, 2004), which will in some way generate economic impact.

This study is relevant because it brings together the literature on Olympic Games of the last decades, becoming a facilitator for future studies on this theme, and also for the chosen approach. The aim is to show both sides of the achievement of a sport mega-event, since one of the divergent points of this literature are studies that argue that the benefits of the mega- sporting events justify the high investments (Chen, 2012) while others indicate that the investments are very high in comparison to the positive results, be they economic or image (Melo, 2014).

2. Method

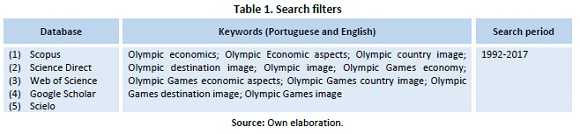

This study has an exploratory nature and is based on a systematic literature review on academic studies that approached the themes: economic aspects of Olympic Games and/or image of the destination (Table 1).

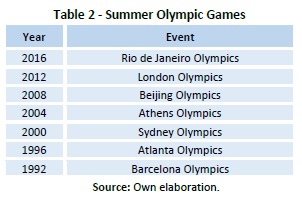

A selection of the studies found was made with the objective of framing them in the same scope. The criteria used to select the articles to be analyzed in the present study were: (a) the studies should address economic and/or destination image impacts for the host country/city of the event; (b) should only deal with Summer Olympic Games that have already occurred, and cannot report prediction for future games in both economic and image attributes. For this work, studies of seven summer Olympic Games were analyzed (Table 2).

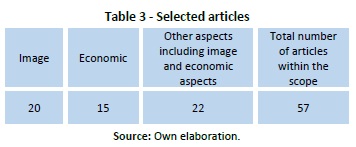

Table 3 indicates the number of articles that fit the scope of the research. From a total of 92 articles initially found, 57 addressed: economic aspects, image aspects, or both, and considered the period after the Olympic Games.

3. Results and discussion

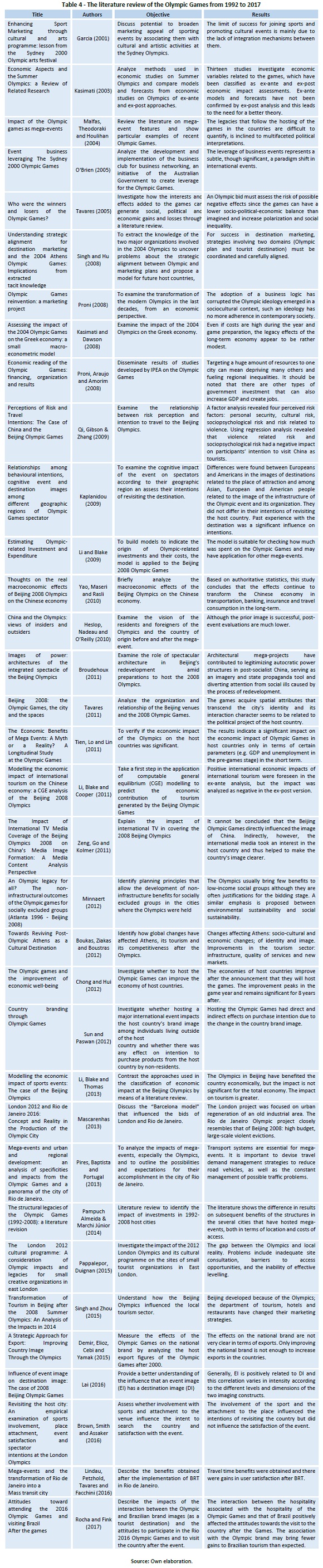

Table 4 shows a summary of the major articles in increasing chronological order.

On positive/negative points of hosting the games, the specifics of each country are highlighted for the result of the impacts. Some points are recurrent such as the economic impact on tourist activity, impacts on strategic areas such as transportation and urban infrastructure, the large sums invested and questions about the possibilities of greater gains if investments were made in areas other than the event, the opportunity cost. Based on the review, an account was made of the main economic/image impacts highlighted in the literature, considering the chronological order of the events.

3.1 Barcelona Olympic Games

On the economic aspects related to the 1992 Olympic Games, the investments for the permanent use of the population generated positive revenues, with positive economic impacts for Barcelona (Proni, 2008; Casellas, Jutgla & Pallares-Barbera, 2010). The main feature of the organization of the event was the high proportion of its own income formed with the contribution of sponsors.

The main programs developed were facilities; services to the Olympic family; telecommunications/electronics; competitions; commercial management; ceremonies/cultural acts; image and security. Civil projects received 61.5 % of investments and construction 38.5 % (Proni, Araujo, Amorim, 2008). It is understood that the most important effects of the 1992 Barcelona projects would be guaranteed over the long term. The main structural projects were the construction of the ring road; a key road to traverse the whole circumference of the city; the opening to the sea, with the construction of the Olympic village; and the creation of several new centers and Olympic zones in Montjuïc, Diagonal and Vall de Hebron (Proni et al., 2008). In addition, a large part of the investment was made in new transport systems and in the rejuvenation of the country’s coast, and a new marina was built on the site (Malfas, Theodoraki, Houlihan, 2004).

Malfas et al. (2004) also stated that from October 1986 to July 1992 the unemployment rate dropped from 18.4 % to 9.6 %, due to the fact that it was necessary to hire a larger number of employees to perform the works related to the preparation of the games. Because of this, the authors emphasize that only a part of the work generated was permanent. The Olympic Games in Barcelona were characterized by geographical decentralization: they were distributed through a series of cities called Olympic sub-hosts (Proni et al., 2008). Only 38.5 % of the Olympic investments were made in Barcelona, while 61.5 % of the projects were carried out outside the metropolitan area, in the rest of Catalonia or were not limited to a certain location, such as investments in the telecommunications sector.

In relation to the image, the Olympic Games that took place in Spain had a positive legacy not only on the part of structural investments for the country but also in obtaining a positive image of it, that could be disseminated throughout the world, strengthening the destination towards other countries and bringing legacies from these transformations to the population (Pampuch, Almeida, Marchi Júnior, 2014).

3.2 Atlanta Olympic Games

According to Malfas et al. (2004), a 2-billion-dollar investment was made in Olympic-related projects between 1990-1996. As a result, more than 580,000 new jobs were created in the region between 1991-1997 and the economic impact of these games on those 6 years was 5.1 billion dollars. Hotchkiss, Morre and Zobay (2003) also highlight the increase in employment but emphasize that there was no increase in wages.

However, many investments were only on paper, the transport system did not perform well, neither did the TI system of the games that had several flaws (Proni, 2008). The investment in security was not enough and the relationship of the population with the visitors was inadequate. Despite this, the games stood out for the good transmission and retransmission of the images and the innovation in relation to the measurement of the results of the competitions. In addition, IBM, a global computer maker, made available technologies to provide the media with real-time information and statistics (Proni, 2008).

Atlanta games did not achieve the non-infrastructure for the population of low income such as the incentive for sport, development of volunteer works, training and educational actions, and a sufficient increase in the number of jobs (Minnaert, 2012). The Atlanta games serve as a telling case of the negative social impacts of a mega-event, 15,000 residents were evicted from public housing projects that were demolished to build Olympic lodgings. In addition, 350 million dollars in public funds failed to be invested in low-income housing, social services, and other support services for homeless and low-income citizens and instead was used in Olympic preparations (Malfas et al., 2004).

Many shelters were converted into lodgings during the games. Financial incentives were offered to social service organizations to convert their facilities into tourist accommodation for two weeks instead of accommodating low-income people. Finally, the Olympic Games in 1996 were financed by private enterprise, with an investment of 1.6 billion, but costs exceeded the forecasts for the games by 2 billion (Proni, 2008).

Regarding the image formed of the USA and Atlanta, no studies were found that reported image gains. However, Proni (2008) reports some negative aspects that contributed to the dissemination of a negative image of the games to the population and to question the readiness of Atlanta to receive the games. The main aspects responsible for this negative image were: safety, athletes’ reception and transportation failures (Proni, 2008). In addition, the tourism in the city was not as expected (Pampuch et al. 2014).

3.3 Sydney Olympic Games

About the economic aspects, 6.5 billion dollars were spent on these Olympics, with more than 3 billion invested in infrastructure and sports facilities (Proni, 2008). The author emphasizes that there have been improvements in pollution control services, the creation of new roads and rail links, improvement in telecommunication, and the electricity service.

The 2000 Olympics organization developed infrastructure- related goals for the local low-income population, focusing on social sustainability. The homeless policy is an example of a lasting result obtained with the games (Minnaert, 2012). For the encouragement of foreign trade tied to the country, during the games, the business club was developed, organized by the federal government of Australia. This event was intended to encourage marketing and leverage relationship networks between Australian and international entrepreneurs (O’Brien, 2005).

For the first time in the history of the Olympic Games, the environment was placed as a priority. Actions such as decontamination of Homebush Bay, placing it as the centre of the Olympic Games; implementation of techniques for reuse of water, energy, waste and concern for sustainable development conveyed the idea that the world needed (Proni et al., 2008). For the authors, the main expenses were sequential: technology; Sydney Olympic radio broadcasting organization; Olympic village; safety; workers; ceremonies and ticket sales. These games still had good repercussions for the local population; the expenses realized were considered valid and legitimate by the majority of the inhabitants (Proni, 2008). There was a strong impact on the local economy. Between 1997 and 2000 GDP was higher by 1.4 billion than it would have been if it had not hosted the games (Proni, 2008).

However, the policy related to the increase in jobs, for example, was not sufficiently explored. The total revenue of the Olympics did not exceed the costs (Proni, 2008). Concerning the image of the country and the city, Australia’s country brand became more popular, and during the years prior to the event, Sydney was classified by the main international publications as one of the cities favoured for the visitation of tourists and executives (Proni, 2008).

Garcia (2001) emphasizes the concern of the image that the country would present to foreigners. Due to this concern, four Olympic art festivals were held from September 1997 to October 2000, each responsible for covering a different aspect of the country’s cultural identity. The festivals were multicultural with focus also on the Aboriginal heritage to arouse curiosity towards the Australian way of life and its culture.

3.4 Athens Olympic Games

The Olympics had a positive impact on the Greek economy. In the period from 1997 to 2005, the games leveraged economic activity at around 1.3 % of GDP per year, while unemployment fell by around 1.9 % per year. For the period from 2006 to 2012, the effect of the games was more modest with GDP increasing by 0.46 and 0.52 % per year and unemployment falling by 0.17 % per year (Kasimati & Dawson 2008). Boukas et al. (2012) highlight improvements in the tourism sector after the mega- event. According to Malfas et al. (2004) 1.4 billion pounds was spent on the opening of new airports. In addition, 820 million pounds were used to expand the city’s subway, which was completed in 2001, in addition, the works of the games allowed the creation of 30,000 jobs (Malfas et al., 2004).

Among the negative aspects to be pointed out are the loss of about 1.5 billion dollars. As a way of trying to control the exacerbated spending, the Greek government announced an audit on the accounts of the organizing committee after the game’s closure. The need to carry out the audit was justified because of reports of over-invoicing and misuse of public resources (Proni, 2008). There were delays in the works, traffic jams and blocking of roads, which triggered the production of a negative image. Large expenditures were made in attempting to meet deadlines and also abandoning facilities built for competitions (Chong & Hui, 2012).

The delay in planning and construction in Athens, in addition to providing bad publicity, was also responsible for questioning by many about the completion of the works and whether the city would be able to prepare on time for the event. The image of the city and the host country also came into question (Chong & Hui, 2012). The authors report that there were three main areas of concern regarding the negative publicity received by Greece during the preparation of the Olympic Games: the slow progress of the works, the non-effective security, and the high price charged for tourists to stay. Various problems of negative publicity could have been avoided if there had been more careful coordination between the Greek national tourism organization and the Athens organizing committee (Chong & Hui, 2012).

3.5 Beijing Olympic Games

Broudehoux (2011) discusses the exuberance in constructions made in Beijing to host the Olympics, Beijing has been redeveloped. The great investment in works had the purpose of projecting the image of a successful economy to foreigners. The event was the most expensive of all time (Proni et al., 2008). The preparation required investments of US$ 34 billion in infrastructure to transform the city and its region. The event brought a number of economic benefits and boosted environmental preservation, confirming the legacy that the Olympic Games have left in their previous staging.

The authors argue that it is likely that the event had a positive influence on Chinese economic development, especially in sectors such as media, television, Internet, mobile phones, “clean” energy and sports equipment. Excitement for the Olympics brought many sectors into a kind of “international revolution”. However, the decisive aspect for the Chinese government does not seem to be the economic impact of the Games, but the demonstration of what China is capable of offering the world.

In addition to airports, new transport systems were built, US$ 40 billion in environmental protection, railways, highways, stadiums and airports were invested in three host cities, Beijing, Shanghai and Qingdao (Chong & Hui, 2012). Receiving the Olympics in Beijing benefited the local population, but these benefits were not significant for the total economy (Li et al., 2013). According to the authors, the larger the economy of the country or city that will host the Olympic Games, the lower the economic impact of hosting the event. In an ex-ante and ex-post study, Li et al. (2011) also found that in terms of tourism, forecasts were more optimistic than the results.

Despite contributions to the city’s infrastructure, about 1.5 million residents were displaced to carry out the works (Tavares, 2011). The redevelopment spectacle, with new architectural constructions designed to obtain an Olympic image of the new Beijing, has managed to divert attention from the growing contradictions in Chinese society (Broudehoux, 2011).

On the image that foreigners have of China, Qi, Gibson and Zhang (2009) indicate that American students view China as a country of moderate risk in relation to personal security, violence, cultural risks and socio-psychological risks. For them, during the Olympic Games, it was less risky to visit the country than at any other time.

3.6 London Olympic Games

This one has few studies, perhaps because it is one of the most recent Olympics. Mascarenhas (2013) reports that the London Olympics sought to modernize and improve the infrastructure of a more degraded area of the city. According to the author, the Olympic Games benefited the city with the improvement in transportation in these areas and having a difference in relation to the other Olympics whereby the number of expropriations carried out was small. Brown, et al. (2016) emphasized the positive intention of revisiting the destination after the games, which implies future economic impacts.

There were also negative points such as the rise in prices in the city and greater peripheralization of the poor (Mascarenhas, 2013). The Olympic cultural programme failed to benefit the small arts organizations because the program goal was not aligned and communicated to the participating artists (Pappalepore & Duignan, 2015). It is noted that the studies found on the London Olympics, unlike the others, did not raise numbers related to the possible economic development coming from the preparation and accomplishment of the event. Nor were there studies that addressed differences in the image of the tourist destination due to the mega-event.

3.7 Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games

The Summer Olympics in Brazil happened in 2016 and it was the most recent edition of the event. Only two articles were found that fit with the filters established for this study: Lindau et al. (2016), Rocha and Fink (2017). The first one focuses more on economic and social aspects since it is related to the transportation investments and transformation that happened in Rio de Janeiro city to be prepared for the Olympic Games. The investments in transit supply began years before the mega-event. The strategy included implementation of an integrated high capacity and performance bus-based transit network fully integrated to the existing boat and heavy rail systems - BRT (Lindau et al., 2016). According to the authors, Rio de Janeiro’s BRT network provides social and infrastructure legacy for the city, offering not only employment opportunities, but recreation and leisure as well. The mass transit increased from 18% to 63%, benefiting almost 1.5 million passengers per day.

Regarding destination image, Rocha and Fink (2017) described the impacts of the interaction between, the brand images of The Olympic Games and Brazil, to the attitudes toward attending the 2016 Rio Olympic Games and visiting the country after the event. The results showed that the interaction between the hospitality associated with the Olympic Games and that of Brazil positively affected attitudes toward visiting the country after the Games. However, in the qualitative part of the study using focus groups with sports management graduate students, they concluded that the association with the Olympic brand might bring fewer gains to Brazilian tourism than expected. One important thing highlighted in this article was the context of the Olympic Games hosted by developing countries. In this situation, the authors defend that the country brand image should benefit more from the association with the event than the opposite.

4. Main findings in the literature

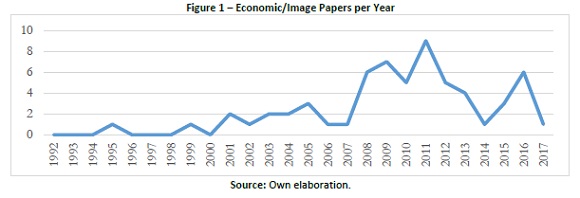

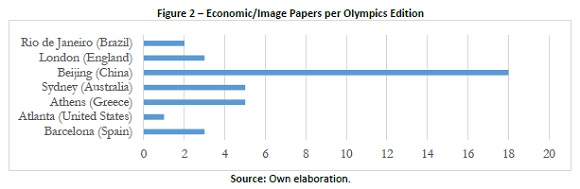

A survey of the main findings from the published literature highlights the large number of publications in the 2000s, especially since 2008, which coincides with the Beijing Olympics in China. It is also observed that among the articles dealing with some specific staging of the Olympic Games, China was the country with the largest number of studies. (Figures 1 and (2). This fact raises some explanatory hypotheses, such as few emerging countries among those that hosted this mega-event in recent staging; it is a country with a social and economic profile different from the others; it still has a relatively closed economy; at the same time it stands out as a strong and growing economy and a large consumer market, generating greater global visibility; finally, it has strong social contradictions, which are also pointed out as negative aspects raised in the articles about destination image (Li & Kaplanidou, 2013; Heslop et al., 2010).

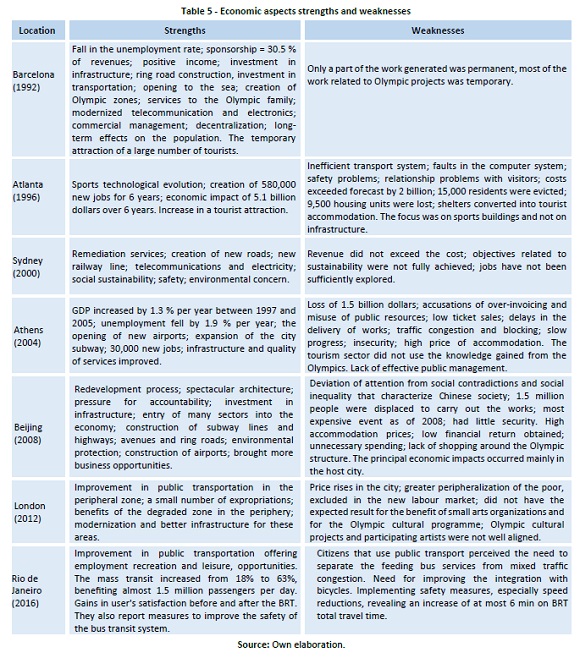

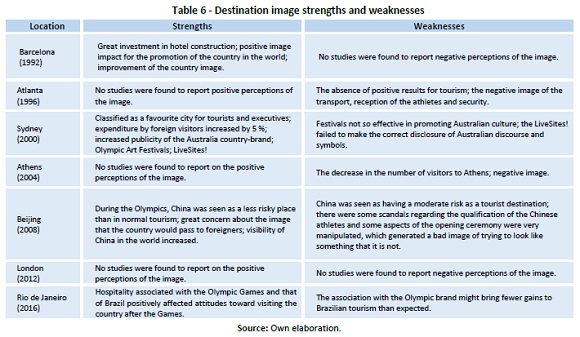

Tables 5 and 6 list the main strengths/weaknesses found in the studies of each of the seven Olympic Games held in recent years.

Regarding the economic aspects, even with the filters considered, articles were found that directly addressed not only economic indicators such as GDP, employment rate, unemployment rate, among others, but mainly of the investments made and expected returns for the realization of the games.

The main items that appeared in the categories of strengths were: increased employment, improved transportation, telecommunications, GDP, infrastructure, and urbanization. The weaknesses were: costs, unduly spent public resources, construction delays, poorer-than-expected results, temporary jobs and lack of investment in infrastructure (peripheralization of the poor, traffic congestion, blocking of roads and inefficient transportation).

Even in articles that deal specifically with the economic impacts of the Olympics, the image is cited as an important factor to justify the mega-event, especially related to tourism activities. However, in spite of the larger number of articles dealing with image, in some more recent stagings such as in Athens, London and Rio de Janeiro, few papers specifically analyzed these image gains for the city/host country.

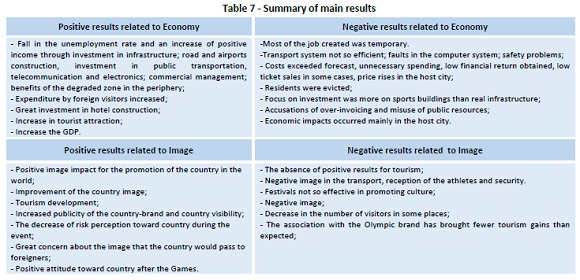

It is observed that in the different stagings of the games, studies were found that indicated image gains/losses. This strengthens the view that the processes of preparation and hosting in each country are too differentiated for the results to be uniform in addition to the specificities of each country. In addition, the diverse methodological aspects in the articles also influence in their results. Table 7 shows a summary of the main studies results.

5. Conclusion

The literature review carried out in this article allowed the proposed objective to be achieved, making a deepening of qualitative analysis related to the theme. The main economic and image implications for the host city of a sports mega-event described in the literature were analyzed.

Although there are specific studies on the subject, many are not delimited to studying the image of a tourist destination or economic impacts. Many of the studies cover several aspects of hosting an Olympic Games regarding the host destination, including the two aspects cited. However, no studies were found that directly related the impacts of the image with the economic impacts in Summer Olympic Games. Such studies would be important since even considering different studies, success cases were observed in which there were economic and image gains (Barcelona and Sydney), and the opposite (Atlanta), which may give indications of the relationship between the two aspects.

The aim of showing the two sides of the accomplishment of a sports mega-event was achieved because articles were found and analyzed that pointed to both positive and negative aspects in relation to the economic and image impacts. However, most of the studies mentioned as positive aspects of those coming from Olympic spending that provided long-term gains for the resident population. While the most cited negative aspects are related to investments that provide benefits in the short term or lack of investment in infrastructure.

Regarding economic aspects, some authors question the gains by highlighting the opportunity cost, that is, how much the destination would gain if the mega-sport investment was made in other areas. In relation to the image, there were few studies of the last Olympics. However, the positive point of literature review articles is that they indicate possible gaps in studies in the area, and this is one of them.

One of the limitations of this article is the number of databases used. Another point to be taken into consideration is that although the Olympic Games are the largest sporting event in the world, there are other events for which research can also be directed.

There is also a lack of ex-post studies on the Olympics. One of the filters of this work was to verify studies of impacts on image and economy after the accomplishment of mega-events and few works were found, taking into account that the Olympic Games are a very old mega-event, indicating that many studies may have been made about the impact forecasting of the events, and few about their effective results.

Future studies should perform ex-post research into the outcome of the Olympic Games by analyzing the economic and image impacts both separately and in relation to each other, which still has not been found in the literature.

REFERENCES

Boukas, N., Ziakas, V. & Boustras, G. (2012). Towards reviving post- Olympic Athens as a cultural destination. Current Issues in Tourism, 15 (1-2), 89-105. [ Links ]

Broudehoux, A. M. (2011). Imagens do poder: arquiteturas do espetáculo integrado na Olimpíada de Pequim. Revista Novos Estudos, 89, 39-56. [ Links ]

Brown, G., Smith, A. & Assaker, G. (2016). Revisiting the host city: An empirical examination of sports involvement, place attachment, event satisfaction and spectator intentions at the London Olympics. Tourism Management, 55, 160-172. [ Links ]

Casellas, A., Jutgla, E. D., & Pallares-Barbera, M. (2010). Creación de imagen, visibilidad y turismo como estrategias de crecimiento económico de la ciudad. Finisterra, 45(90), 153-172. [ Links ]

Chen, N. (2012). Branding national images: The 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics, 2010 Shanghai World Expo, and 2010 Guangzhou Asian Games. Public Relations Review, 38, 731-745. [ Links ]

Chong, T. T. L. & Hui, P. H. (2012). The Olympic Games and the improvement of economic well-being. Quality-of-Life Studies, 8(1), 1- 14. [ Links ]

Demir, A. Z., Elioz, M., Cebi, M., Cekin, R., & Yamak, B. (2015). A strategic approach for export: Improving country image through the Olympics. Anthropologist, 20(3), 457-461. [ Links ]

Deng, Q. & Li, M. (2013), A model of event-destination image transfer. Journal of Travel Research, 53(1), 69 -82. [ Links ]

Garcia, B. (2001). Enhancing sport marketing through cultural and arts programme: Lesson from the Sydney 2000 Olympic arts festival. Sport Management Review, 4, 193-219. [ Links ]

Gibson, H. J., Qi, C. X. & Zhang, J. J. (2008). Destination image and intent to visit China and the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games. Journal of Sport Management, 22, 427-450. [ Links ]

Getz, D. (1993). Festival and special events, in M. Khan, M. Olsen, & T. Var (Eds.). VNR’s Encyclopedia of Hospitality and Tourism. New York: Van Nostrand Rheinhold.

Heslop, L. A., Nadeau, J. & O’Reilly N. (2010), China and the Olympics: views of insiders and outsiders. International Marketing Review, 27(4), 404 - 433.

Hiller, H. H. (2006). Post-event outcomes and the post-modern turn: The Olympics and urban transformations. European Sport Management Quarterly, 6(4), 317-332. [ Links ]

Hotchkiss, J. L., Moore, R. E. & Zobay, S. M. (2003). Impact of the 1996 Summer Olympic Games on employment and wages in Georgia. Southern Economic Journal, 69(3), 691-704. [ Links ]

Kaplanidou, K. (2009). Relationships among behavioural intentions, cognitive event and destination images among different geographic regions of Olympic Games spectators. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 14(4), 249-272. [ Links ]

Kasimati, E. & Dawson, P. (2008). Assessing the impact of the 2004 Olympic Games on the Greek economy: A small macro-econometric model. Economic Modelling, 26, 139-146. [ Links ]

Kasimati, E. (2003). Economic aspects and the Summer Olympics: A review of related research. International Journal of Tourism Research, 5(6), 433-444. [ Links ]

Knott, B., Fyall, A. & Jones, I. (2015). The nation branding opportunities provided by a sport mega-event: South Africa and the 2010 FIFA World Cup. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 4, 46-56. [ Links ]

Lai, K. (2016). Influence of event image on destination image: The case of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 7, 153-163. [ Links ]

Li, S. N. & Blake, A. (2009). Estimating Olympic-related investment and expenditure. International Journal of Tourism Research, 11(4), 337-356. [ Links ]

Li, S. N., Blake, A. & Cooper, C. (2011). Modelling the economic impact of international tourism on the Chinese economy: a CGE analysis of the Beijing 2008 Olympics. Tourism Economics, 17(2), 279-303 [ Links ]

Li, S., Blake, A. & Thomas, R. (2013). Modelling the economic impact of sports events: The case of the Beijing Olympics. Economic Modelling, 30, 235-244. [ Links ]

Li, X. R., & Kaplanidou, K. K. (2013). The impact of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games on China’s destination brand: A US-based examination. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 37(2), 237-261.

Lindau, L. A, Petzhold, G., Tavares, V. B. & Facchini, D. (2016). Mega- events and transformation of Rio de Janeiro into a mass-transit city. Research in Transportation Economics, 59, 196-203. [ Links ]

Malfas, M., Theodoraki, E. & Houlihan, B. (2004). Impacts of the Olympic Games as mega-events. Municipal Engineer, 1557(M3), 209-220. [ Links ]

Mascarenhas, G. (2013). Londres 2012 e Rio de Janeiro 2016: conceito e realidade na produção da cidade olímpica. Revistas Continentes, 2(3), 52-72. [ Links ]

Melo, L. M. (2014). Experiences from World Cup 2010 in South Africa - first thoughts about the implication for Brazil 2014, Retrieved August 25, 2016, from http://www.ie.ufrj.br/datacenterie/pdfs/seminarios/pesquisa/texto1904.pdf .

Minnaert, L. (2012). An Olympic legacy for all? The non-infrastructural outcomes of the Olympic Games for socially excluded groups (Atlanta 1996 - Beijing 2008). Tourism Management, 33, 361-370. [ Links ]

Müller, H. & Moesch, C. (2010). Infrastructure repercussions of mega sports events: The relevance of demarcation procedures for impact calculations, evaluated using the case of UEFA Europe 2008. Tourism Review, 65(1), 37-56. [ Links ]

O’Brien, D. (2005). Event business leveraging: the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(1), 240-261. [ Links ]

Pampuch, M., De Almeida, B. S. & Marchi Júnior, W. (2014). Os legados estruturais dos Jogos Olímpicos (1992-2008): uma revisão de literatura. Educação e Humanidades, 1(7), 1-15. [ Links ]

Pappalepore, I. & Duignan, M. B. (2015). The London 2012 cultural programme: A consideration of Olympic impacts and legacies for small creative organizations in East London. Tourism Management, 54, 344-355. [ Links ]

Pike, S. & C. Ryan. (2004). Destination positioning analysis through a comparison of cognitive, affective, and conative perceptions. Journal of Travel Research, 42, 333-42.

Pires, L. S., Baptista, L. F. & Portugal, L.S. (2013). Megaeventos e o desenvolvimento urbano e regional: uma análise das especificidades e impactos provenientes dos jogos olímpicos e um panorama para a cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Anais: Encontros Nacionais da ANPUR, 15.

Proni, M. W. (2008). A reinvenção dos jogos olímpicos: um projeto de marketing. Esporte e Sociedade, 3(9), 1-35. [ Links ]

Proni, M. W., Araujo, L. S. & Amorim, R. L. C. (2008). Leitura econômica dos jogos olímpicos: financiamento, organização e resultados. Rio de Janeiro: IPEA. [ Links ]

Qi, C. X., Gibson, H. J. & Zhang, J. J. (2009). Perceptions of risk and travel intentions: The case of China and the Beijing Olympic Games. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 14(1) 43-67. [ Links ]

Rocha, C. M. & Fink, J. S. (2017). Attitudes toward attending the 2016 Olympic Games and visiting Brazil after the games. Tourism Management Perspectives, 22, 17-26. [ Links ]

Singh, N. & Hu, C. (2008). Understanding strategic alignment for destination marketing and the 2004 Athens Olympic Games: Implications from extracted tacit knowledge. Tourism Management, 29, 929-939. [ Links ]

Singh, N. & Zhou, H. (2015). Transformation of tourism in Beijing after the 2008 Summer Olympics: An analysis of the impacts in 2014. International Journal of Tourism Research, 18(4), 277-285. [ Links ]

Sun, Q. & Paswan, A. (2012). Country branding through Olympic Games. Journal of Brand Management, 19(8), 641-654. [ Links ]

Tavares, O. (2005). Quem são os vencedores e os perdedores dos jogos olímpicos? Pensar a prática, 8(1), 69-84. [ Links ]

Tavares, O. (2011). Beijing 2008: os Jogos Olímpicos, a cidade e os espaços. Revista Brasileira Ciência e Esporte, 33 (2), 357-373. [ Links ]

Tien, C., Lo, H. C. & Lin, H. W. (2011). The economic benefits of mega-events: A myth or a reality? A longitudinal study on the Olympic Games. Journal of Sport Management, 25, 11-23. [ Links ]

Yao, L., Maseri, W. & Rasli, A. (2010), Thoughts on the real macroeconomic effects of Beijing 2008 Olympics on Chinese economy. Asian Journal of Information Technology, 9(2), 32-36 [ Links ]

Zeng, G., Go, F. & Kolmer, C. (2011). The impact of international TV media coverage of the Beijing Olympics 2008 on China’s media image formation: a media content analysis perspective. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 12 (4), 39 - 56.

Guest Editors:

· J. A. Campos-Soria

· J. Diéguez-Soto

· M. A. Fernández-Gámez

Received: 12.08.2017

Revisions required: 14.01.2018

Accepted: 20.06.2018