Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.14 no.3 Faro set. 2018

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2018.14307

MANAGEMENT: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Forgotten customers, inclusive customers: personal values and coproduction of physically disabled persons in leisure consumption

Clientes esquecidos, clientes incluídos: valores pessoais e coprodução dos deficientes físicos no consumo de lazer

Nuno Álvares Felizardo Jr.1, Irene Raguenet Troccoli2, Patrícia Leite da Silva Scatulino3

1Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Instituto Federal do Sudeste de Minas Gerais, Brazil, nuno.felizardo@ifsudestemg.edu.br

2Universidade Estácio de Sá, Brazil, irene.troccoli@estacio.br

3Universidade Estácio de Sá and Universidade FUMEC, Brazil, patricialeiteadm@hotmail.com

ABSTRACT

Physically disabled customers (PDCs) in Brazil face numerous obstacles in their social role as consumers, in spite of their significant share of the population. Their low visibility implies they are not seen for what they really are: potential consumers. Consequently, they often cannot satisfy their wishes or achieve personal values through the acquisition of products and services. This suggests an investigation of the major reasons behind their consumption practices related to personal values. Using the soft laddering technique, this study shows that happiness and freedom are the personal values achieved by PDCs while enjoying beachside recreation activities. Non-participant observation and the priming stimulus of the five human senses were simultaneously used to investigate the intersection of these values with the stimuli offered by the service providers to these customers to co-produce the service. Finally, further investigation is suggested as to why, contrary to common sense, social belonging was not one of the personal values identified.

Keywords: Physically disabled customers, coproduction, soft laddering, personal values, priming.

RESUMO

Clientes com deficiência física no Brasil enfrentam inúmeros obstáculos para exercer papel social no ato de consumir, muito embora quantitativamente sua participação na população seja significativa. Sua baixa visibilidade convida a investigar quais os motivos mais profundos, traduzidos em valores pessoais, que se encontram por trás do seu consumo. Utilizando a técnica de soft laddering, este artigo constata que felicidade e liberdade são os valores pessoais dessas pessoas que se destacam no seu consumo de lazer praiano. Em paralelo, foi utilizada a observação não participante e tipologia de estímulos de priming nos cinco sentidos humanos para investigar qual a interseção desses valores com os estímulos oferecidos pelos prestadores para que esse cliente exerça papel de coprodutor do serviço. Ao final, propõe-se a investigação de por que - contrariando uma suposição trazida pelo bom senso - o pertencimento social não fez parte dos valores pessoais identificados.

Palavras-chave: Clientes com deficiência, coprodução, soft laddering, valores pessoais, priming.

1. Introduction

In 2010, there were 45.6 million Brazilians with some kind of disability, meaning special physical needs (visual, hearing, motor, or mental). Among them, 13.3 million had a specific physical disability (IBGE, 2010). That is, approximately 24% of the Brazilian population was physically disabled to some extent, and of these 29% had some motor disability which impaired their natural mobility.

A physical disability does not prevent a person from having consumption needs (Ruddell & Shinew, 2006). When they enter retail stores, their greatest desire is to be seen as regular consumers (Baker, Holland & Kaufman-Scarborough, 2007). In the service marketing literature, this phenomenon is supported by the construct of simultaneity (Zeithaml, Parasuraman & Berry, 1985), according to which as co-creators of value in service production, customers are active agents (Vargo & Lusch, 2004a, 2004b).

However, physically disabled customers (PDCs) face numerous obstacles when acting as consumers. While in the mid-1990s, few salespeople and service personnel were trained to serve PDCs (Kaufman, 1995; Burnett, 1996), little change was observed in subsequent years (Saeta & Teixeira, 2008; Hogg & Wilson, 2004) and there continue to exist few people trained properly to provide these services (Faria, Silva & Ferreira, 2012; Mano, 2014; Barbosa, 2014; Silva et al., 2015).

This implies that retail services provided to PDCs in Brazil have low quality, since these people are not seen as what they really are: potential consumers, able to generate profits (Lages & Martins, 2006), but who cannot satisfy their wishes or achieve personal values through the acquisition of products and services.

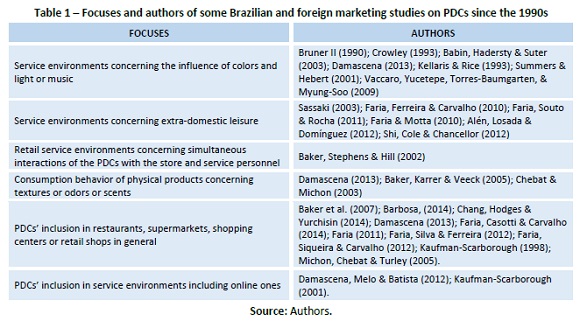

This apparent lack of interest of Brazilians who directly interact with these consumer’s contrasts with various studies found in the recent business administration literature, most of them developed in different research environments, aimed at analyzing, improving and understanding the specificities and opportunities offered by PDCs. For the sake of parsimony, a brief extract of a more complete survey carried out in late 2015 is shown in Table 1. It should be noted that only the study carried out by Chang, Hodges and Yurchisin (2014) in the clothing retail sector involved the personal values of PDCs.

Using the soft laddering technique, the present study aimed to investigate which personal values of PDCs are achieved when they engage in leisure activities. Additionally, using non-participant ethnography (NPE), it investigated how these values are expressed by PDCs when they are co-producers of leisure services.

The present study adds knowledge to the means-end theory and to the principle of service co-production with the consequent value co-creation. In fact, when considered in this academic field, PDCs are usually included in investigations that focus on specific issues, with emphasis on social inclusion at work (Granger & Kleiner, 2003; Jones & Schmidt, 2004). Their presence in also small in investigations regarding tourist services, and when this is done, the focus normally is not directed to their behavior as consumers, but rather to aspects regarding their accessibility based on legal requirements (Goulart, 2007; Lages & Martins 2006).

The bibliometric survey carried out by Faria and Carvalho (2013), involving 10,983 papers in the 2000 to 2010 editions of Encontro da Associação Nacional de Pós-Graduação e Pesquisa em Administração (EnANPADs) to find studies that involved PDCs, confirms this low interest. Only 41 articles were found, meaning no more than 0.37% of the total, concentrated in only five categories: three in marketing, seven in people management and work relationships, 18 in organizational studies, six in public administration, and seven in information management.

This low interest is food for thought. In the case of research in the public administration area, it is worth remembering that the inclusion of PDCs in organizations, rather than signaling goodwill to improve their image in society, is nothing more than the recognition of an inclusion right guaranteed by law (Ribeiro & Carneiro, 2009).

In the case of marketing research, a similar criticism is pertinent:

Brazilian academics in marketing seem to underestimate the chances of research oriented towards understanding the needs of all PDC segments. In order to put into practice the concept of "marketing orientation" and to give disabled people the right to be heard as customers, it is recommended that marketing students dedicate themselves to themes such as PDC behavior; adaptation of the marketing mix to PDC needs; relationship marketing aspects aimed at PDCs; Endomarketing aspects aimed at physically disabled employees; and ethical issues involving consumption and minority groups, including institutions that focus on protecting PDCs. (Faria & Carvalho, 2013, p. 56)

Our intention here is to fill this gap by increasing existing knowledge regarding what influences PDCs in their service consumption options. It is divided into four more sections: a brief literature review, description of the method, results of the primary research, and discussion.

2. Literature review

2.1 Experiential marketing and hedonic consumption

Experiences "are individual events that occur in response to some stimulus" (Schmitt, 2000, pp. 74-75). These stimuli cause diverse reactions in consumers, affecting their senses, feelings and/or their frames of mind.

A good experience is always memorable and extraordinary (Pine & Gilmore, 1999), and allows consumers to explore all their senses (Schmitt, 1999). Thus, a well-met expectation provides the consumer an opportunity to physically, mentally, emotionally, socially, and spiritually engage in the consumption of a product or service, making the interaction significantly real (Caru & Cova, 2003; Gentile, Spiller & Noci, 2007).

Hedonic consumption fits into the experiential view of consumption (Lucian, Farias & Salazar, 2009; Gomes, Anne, de Azevedo Barbosa, & Gomes de Souza, 2013), which deals with sensory, aesthetic and emotional aspects that lead the consumer to evaluate the "extended" costs, benefits and advantages of the product (Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982).

In this context, emotions are felt not only with the consumer’s senses, since they can also be generated by mental stimuli and memories of previously lived experiences (Zeitham, Bitner & Gremler, 2014). The idea of so-called hedonic consumption is related to the "facets of consumer behavior regarding the multisensory, imaginary, and emotive aspects of someone’s experience with products" (Hirschman & Holbrook, 1982, p. 92). It can also be seen as the value perceived by the customer regarding the qualitative and quantitative factors that interact with the subjective and objective parts, which leads to a complete shopping experience (Babin, Darden & Griffin, 1994).

That is why there are three lines of research aimed at identifying the hedonic facets and the utilitarian properties of products (Hernandez, 2009): consumers’ characteristics, products’ and brands’ characteristics, and the perceived value obtained from a purchase.

The last line of research (value perceived from a purchase or from use of a service) is supported by studies that confirm that consumers tend to acquire hedonic products that are used for entertainment, fun and pleasure, instead of for utilitarian purposes (Katz & Sugiyama, 2006; Park, 2006; Gill, 2008). In other words, this means value is "(...) consumers’ perception of what they want to happen (consequences) in a specific situation of use, with the aid of some product or service offered to achieve some proposal or goal" (Woodruff & Gardial, 1996, p. 54).

The present study aims to identify the value that arises from experiential consumption of a typically hedonic beach leisure activity. First, though, it is necessary to better understand the complex construct of personal value.

2.2 Customers’ personal values

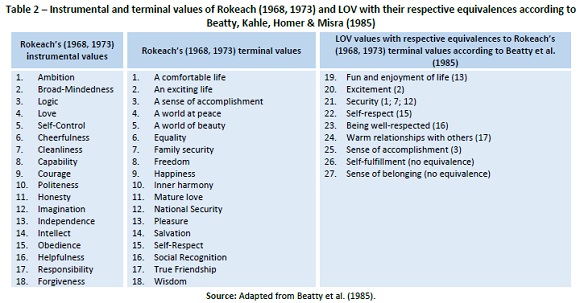

The complexity of the construct “personal values” has led several authors to first organize the elements that form it, using tools such as the Rokeach Value Survey (RVS) and the list of values (LOV) (Table 2).

According to RVS, personal values are the end-states of life, consisting of the aims and goals of one’s life (Rokeach, 1973). This survey form contains 36 types, divided into two sets of equal sizes: 18 terminal values, meaning desirable end-states or goals sought in life, such as pleasure and freedom; and 18 instrumental values, meaning ways of being and means or behavioral patterns through which those goals are sought, for example, by being self-controlled.

The study of PDCs’ personal values while enjoying beachside recreation activities leads to a second investigation: how these PDCs act as autonomous creators and producers of value when interacting with the service providers, i.e., through co-creation and co-production.

2.3 Co-production and co-creation of value

Value co-production and co-creation are not synonyms, so they should not be confused with each other. Co-production of value may or may not generate mutual value (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004), whereas co-creation of value refers to value created jointly between provider and customer, within the dominant service logic (Grönroos & Ravald, 2011).

Thus, co-production precedes co-creation, i.e., co-production of value does not guarantee that co-creation of value took place: "(...) this term [co-creation] refers to the customers’ involvement in the production process (co-production) as well as to their involvement in other activities that are relevant to the provider, such as the design and development of new products and services, as well as their maintenance" (Morais & Santos, 2015, p. 228)

However, the identification of this relationship of co-creation of value requires its measurement, to contrast the moments of stimuli during the use of services. One such line of research uses the goal-setting theory (Locke & Latham, 1990, 2002): "(...) high (difficult) goals lead to a higher level of task performance than easy or vague and abstract goals, such as ’doing your best’ " (Locke & Latham, 2006, p. 265).

This focus on subconscious goal designation refers to a new and systematic technique for organizations, so that customers, once reminded of past successful behaviors, properly perform their roles as co-producers of a service.

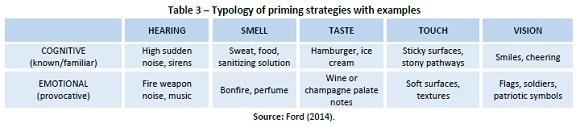

Having in mind that the more clues (or stimuli) of priming are given to the customer, the stronger will be their influence on the resulting answers, there is a typology about how this process can occur, based on the five human senses and subdivided into cognitive and emotional aspects (Ford, 2014) (Table 3).

This tool, used together with personal values, helps identifying moments during which processes and methods stimulate customers to achieve their terminal values while enjoying beachside recreation activities through co-creation interactions.

3. Method

Based on the means-end theory (Reynolds & Olson, 2001), this study is qualitative-quantitative, descriptive, exploratory, bibliographic and ethnographically-inspired by non-participant observation (NPO) (Gil, 2012). The primary field research was carried out in December 2015 and January 2016, using the soft laddering interview technique.

Method triangulation aimed at increasing the quality of the results (Flick, 2009) and at better obtaining the intersection of the values identified with the stimuli offered by the providers for the customers to act as service co-producers.

The beachside recreation activity service provided to the PDCs was that offered by the Barra da Tijuca unit of the Praia para Todos (Beach for All) project, described in the following subsection.

In order to identify which personal values of the PDCs are satisfied during the leisure services of the project, soft laddering interviews were carried out in loco to gather and analyze primary information, soon after the activities to preserve the recall of the experience.

The researcher carried out the NPO during his visit to the project, meaning he was immersed in that environment. On these occasions, attitudes and reactions not mentioned during the soft laddering interviews were sought, taking advantage of one of the main advantages of the NPO method, whereby: "(...) facts are directly perceived, without any intermediation. In this way, subjectivity, which permeates the entire process of social research, tends to be reduced" (Gil, 2012, p. 100).

3.1 Praia para Todos project

Located in the city of Rio de Janeiro, this project ensures beach access to differently disabled people, supplying them with several physical resources, such as a sand footbridge for wheelchairs, and amphibious chairs that allow PDCs to enter the sea. The services are rendered by a team formed by health professionals and volunteers, to enable PDCS to participate in various beach leisure activities, two of which were the focus of this study: sea bathing and sitting volleyball (Instituto Novo Ser, 2016).

The project started in 2013 at Copacabana beach, located near Lifeguard Post 6, and was later extended to Lifeguard Post 3 at Barra da Tijuca beach. Initially it aimed at just facilitating sea bathing for PDCs. Over time, the free activities were diversified, including beach leisure ones, always supported by the necessary accessibility.

During the field research for this paper, the project offered PDCs sitting volleyball, adapted surfing, stand-up paddling, hand biking, beach soccer for blind people, Brazilian paddle ball, and recreational games. These activities, added to the environment where they are performed, provide hedonic experiences to the users and allow them to escape from the routine of pain, very common in their daily life.

Obviously, physical adjustments are necessary to allow PDC to engage in activities in such a naturally unfriendly environment for people with locomotion disabilities, aimed at guaranteeing their participation in the various activities offered. Examples are reserved parking spaces, accessibility conditions near lifeguard posts for all disabled people (such as ramps to access the sidewalk and support bars), floating amphibious chairs that are easily moved on the sand and float in the water, treadmill for personal wheelchairs, ramps to access the sand, and sound signs to help the visually impaired to cross the street.

In addition to these physical adjustments, human resources on the beach complete the necessary structure for totally or partially physically disabled people to experience beach leisure activities. Approximately 25 people (paid or unpaid by the project) work in the project area, divided into two categories:

1) technical team: formed by experts in sports education, physical therapy and occupational therapy, as well as interns, they allow integration activities and the necessary safety conditions for the PDCs; and 2) volunteers.

3.2 Subjects

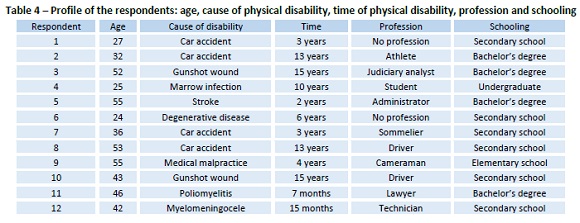

Twelve PDCs were interviewed (excluding visually impaired people). All were paraplegic or hemiplegic, male, aged between 24 and 55 years, had different professions, and had already attended the project at least three times (Table 4).

3.3 Analysis of the evidences

Evidence from the soft laddering interviews was analyzed according to Ikeda, Campomar and Chamie (2014):

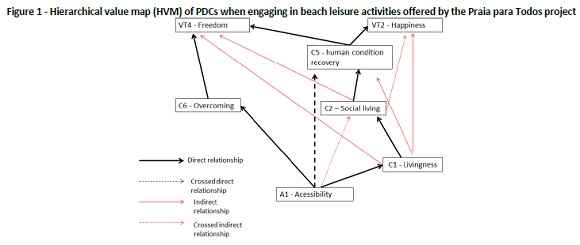

1) Analysis was performed manually, with no software aid, and a hierarchical value map (HVM);

2) Values were identified using LOV and Rokeach’s proposal (1968, 1973), involving 18 instrumental values and 20 terminal values, since according to Beatty et al. (1985), seven of the nine values of LOV are equivalent to Rokeach’s (1968, 1973) terminal values.

3) Consequences and values were not split into two levels, according to experts in the laddering technique; and

4) The qualification of the elements as attributes, consequences and values was carried out solely by the author, using the guidelines of other authors (Reynolds & Gutman, 1988; Valette- Florence & Rapacchi, 1991) who have suggested listing attributes, consequences and values indicated by PDCs after analyzing data from interviews. These elements were coded and counted to determine how many times each one was identified in the interviews. This method implied 36 individual ladders.

Subsequently, a square implication matrix was constructed, the chains were identified, and finally, a hierarchical value map (HVM) was constructed, the last step before interpreting the results: finding the dominant perception, which serves to suggest the chains that most contributed to the result. This dominance, however, was not identified, since each chain, regardless of the number of direct or indirect relation, appeared only once.

The NPO allowed checking the project environment and the development of the activities, which helped to understand the operational aspects that allow PDCs to use what is offered to them - sea bathing, volleyball, soccer.

The observations were recorded in a field diary, a relevant step to compare the changes that occurred during the study (Latour, 2005). Then this information was analyzed and interpreted, and the diaries from the different surveys were consolidated into a single structured text. The NPO provided the following benefits:

1) It helped understand the actions and feelings brought by the physical conditions that assure the proper enjoyment of leisure activities (for example, facilitation of access the beach), the relationship between the PDCs and those who work with the project, and the contribution of the PDCs to the proper accomplishment of the activities;

2) It helped to better understand the evidence from the soft laddering interviews, and to clarify attributes, consequences and values that possibly would not be so clear if only the conversations were considered;

3) It was useful to further learn about the personal values that emerged from these conversations and to better understand the intersection of these values with the initiatives taken by the project team members on the beach to stimulate the performance of the PDCs’ roles as co-producers of the service during its use; and

4) It was useful to discover which actions carried out by the members of the project helped and stimulated the PDCs in the leisure activities, a parallel analysis to the laddering interviews that helped interpret the terminal values that emerged.

Due to space limitation, the results of the primary research in the following section meet the objectives of this study, but contain no details about the NPO or about the analysis of the gathered evidence. Only excerpts of the comments obtained in this phase of the study are cited.

4. Results of the primary research

The HVM of the PDCs who engage in the leisure activities offered by the Praia para Todos project is shown in Figura 1.

Given the facts already indicated in the method section, it is not surprising that accessibility was the only abstract attribute found during the laddering interviews: without the initiatives that guarantee the special physical conditions for this public, none of those PDCs would be able to enjoy the activities: "[...] When I had the accident, the beach became something inaccessible, completely inaccessible... I used to see the beach from the pavement; I didn’t think of of the possibility of one day being here on the sand... [...]" (Respondent 8).

There were four psychological consequences in the HVM: livingness, social living, overcoming, and human condition recovery. Livingness and social living are directly related to the harmonious and attentive environment created to receive people who have experienced exclusion:

(...) here in the project, we are more at ease, we can talk about other subjects, about leisure, fun... We [referring to the other PDCs] arrange to go out, we go to the movies, to the theater; the guys arrange to go out, there will be a carnival event with the guys, I’ve arranged it here... (Respondent 6).

The overcoming and human condition recovery can be interpreted as a result of recovering pleasure in life and well- being, which are affected when total or partial loss of mobility leads to depressing changes in lifestyle:

I have the potential of overcoming, of self-overcoming. We’ve got to overcome, dude, life goes on, I can’t stop living. Look at the good things there are on this beach! Is there any reason for me to be sad, man? (Laughs) I’m with my friends, who I like, I am laughing, I am digging it, it’s good (Respondent 6).

These consequences provided by the human and structural characteristics of the project allow the PDCs to achieve their terminal values (Rokeach, 1968, 1973), which, according to this study, are two: happiness and freedom.

These values were mentioned several times in the interviews, even if not explicitly, but in gestures and expressions. It was possible to notice both values in the imaginary of the respondents:

[Taking part in the project] It gives me a feeling of freedom, of being able to do everything I could do before depending on accessibility... Going into the sea, which is difficult in these conditions, and seeing so many people having the same needs and overcoming ... (Respondent 5);

It was an achievement for me to go back into the water, I used to be a surfer, and I had not gone back in the water after the accident... The project gave me this... This happiness... (Respondent 5);

I have a feeling of happiness when I’m in the project... I enjoy the activities, everything, understood? It’s really great here! (Respondent 7).

After identifying the terminal values of the PDCs, the second part of the study began: to identify the intersection of these values with the stimuli offered by the professionals and volunteers so that the PDCs could co-produce the service.

For this purpose, the findings from the NPO and the theoretical references were used, taking into account the typology of priming strategies (Ford, 2014). Thus, all the reactions to sensory stimuli that led the PDCs to express feelings that could be related to the terminal values found in the HVM, were recorded in the field diary, to show the relationship between what the service providers did and these values.

Several observations made while investigating the sensory stimuli produced by the service providers during the activities together with the PDCs allowed identifying a relationship between co-production and co-creation of value, which triggered reactions related to the identified terminal values:

Through the sensory stimulus of hearing, for example, during the sitting volleyball matches, members of the technical team encouraged the PDCs, by acting as fans. At this moment, there was co-production of value, with the "fans" playing their role (as in any match) of creating a lively and stimulating environment. This behavior aimed to encourage involvement of the PDCs in the activity, although they frequently seemed oblivious of this cheering (again as players in any match). There was also co-creation of value: with each point scored, both the team and fans celebrated, a clear manifestation of joy characteristic of any sports environment, when the terminal value happiness could be easily noted.

Another example was during sea bathing, when the sensory stimulus of hearing was triggered for interaction of the PDCs with the water, through several verbalizations that expressed the pleasure of the moment ("Today the water temperature is great") or that aimed at creating an atmosphere of joy ("Watch out for the wave!", "Watch out for the shore break.” In these situations, there was co-production: when PDCs asked the members of the technical team about the feeling of being submerged or when they expressed the (impossible) desire to body surf, the technical team was stimulated to perform these activities themselves to transfer to the PDCs feelings to lessen their frustration.

Another case of co-production was verified in the case of PDCs who, for any reason, could not be taken into the sea and only stayed at the water’s edge, but still took pleasure. This situation created a "middle ground" regarding the experience, since the team members used their hands and even buckets to wet the body of the PDCs. In this case, the feelings of the PDCs were guaranteed by the sensory stimulus of touch, usually translated into comments about the water temperature.

In the same way, when the PDCs entered the water using the amphibious chair (which was introduced backwards to prevent the frontal crash by waves), it was possible to observe the co- creation of value between both parties, since the hearing stimulus involved encouragement and warning, usually "Watch out for the wave!". This utterance not only sounded like a warning of the arrival of a wave, it was also an important part of the sea-bathing experience: being enveloped by salt water, "not being able to avoid that pleasant contact.

At this moment, there was usually a look of concern in the PDCs, since they had no idea of the strength of the waves, but then the team members celebrated the successful experiment with exclamations such as "Woo-hoo!", in a reaction that refers to the terminal value happiness, this feeling became visible in the PDCs’ relieved faces, always culminating with everyone laughing.

Also at this time, the sensory stimulus of vision played a role in the co-production and co-creation of value, since when taking PDC to the water using the amphibious chairs, the technical team (respecting the characteristics of the disabilities and the ages of the PDCs) simulated a race to the water. This behavior involved visual stimulus to the PDCs, who saw themselves being taken to the water at a speed most of them had not experienced since becoming disabled, reinforcing their feeling and experience.

During these moments, in a reaction that refers to the terminal value freedom, it was not uncommon for the PDCs to smile, to let out cries of satisfaction, and to close their eyes to feel the wind against their face (in a reinforcement of the sensory stimulus touch) during this faster movement, demonstrating joy by the feeling of being able to escape their limitations.

At this moment, co-production was translated into the cries of "faster, faster" made by the PDCs as the sea got close; and value was co-created because this manifestation (to "run" to the sea) encouraged the technical team members to participate in the experiment, and helped them understand the contribution of this action to the experience of the PDCs.

Co-production and co-creation of value were materialized when the PDCs asked to remain in the water without the aid of the chair (floating only with the help of the team members’ hands) so that their body could have total contact with the water - expressing the freedom from the physical contact of orthopedic appliances.

The sensory stimulus taste was also triggered in the building of experience when, in the extreme, PDC who had never been to the sea were encouraged by the team members to taste the salinity of the sea. The co-creation of value at this moment was due to the interest of the PDCs to learn something new, since locomotion difficulties had prevented many of them from getting close to the ocean. The reaction at this moment had to do with terminal value happiness: after a moment of repulsion to the bitter taste of salt, the PDCs relaxed due to the new experience, and then roared with laughter.

5. Discussion

From these findings, the existence can be argued of transcendence from the "functionality" of sea bathing as a mere service to an event that provides an intangible benefit to the customer, translated into return of value from the consumed service (Morais & Santos, 2015).

The intersection of this co-creation of value with the personal values happiness and freedom was observed when the technical team members exceeded the "technical" aspects of the services, interacting with the PDCs in a relaxed manner, which invariably triggered playful reactions of both parties.

Both PDCs’ and service providers’ faces showed happiness when the PDCs were in the water interacting with the team or playing volleyball and listening to the fans. The PDCs’ faces showed a feeling of freedom (when they closed their eyes to enjoy the moment) and of happiness - as did the team members faces during the "race" of the amphibious chair to the sea. It was a moment in which reactions like smiles and shouts of excitement reflected perfect interaction between the parties at a moment of pure pleasure and feelings of communion.

A significant example comes from the moment when PDCs asked to float on the water without the aid of the amphibious chair, leaving their body (practically) free. This request can be interpreted as a desire for a maximum feeling of freedom: even if only for a few minutes, where the PDCs feel free from their limitations and from any equipment necessary to get around.

This finding is similar to that of Mano (2014), who specifically investigated the personal factors - but not the personal values - along with the structural and sociocultural factors related to consumption of PDCs in supermarkets and hypermarkets, to identify the feeling of freedom engendered by being able to consume in this retail setting. In this case, the happiness found as a terminal value of the consumption of beach leisure in the study described here, even though not explicitly stated, finds a parallel in various statements by the people interviewed by Mano (2014), who expressed feelings such as self-confidence from overcoming barriers imposed by physical limitations and society.

The results of this study also corroborate those of Chang, Hodges and Yurchisin (2014), who investigated the meanings of dress styles to PDCs and how their choice of clothing is related to their health and well-being. In this respect, those authors showed that this meaning refers to two themes - interpreted as reasons behind the choice of clothes as an expression of identity - which served to show that these people, like all consumers, express various values that depend on the act of consumption: self-efficacy, a feeling that finds parallel in the instrumental value “independence” of Rokeach (1973); and symbols of victory, referred to, by Beatty et al. (1985), as the feeling of mission accomplished.

In this light, the Praia para Todos project transcends a mere inclusive project for its regular participants. It is seen as a place of interaction, friendship, human condition recovery, freedom by overcoming physical limitations. In short, this is were happiness is possible for someone who once thought life had ended. People help each other, include each other and feel reborn.

These phenomena originate from the co-production between customers and service providers. In addition to carrying out the activities, the members of the technical team transcend their roles. They have a higher responsibility of ensuring an interactive environment that allows the PDCs to overcome their limitations and, with excitement and a strong emotion, to have an experience optimized despite their physical dependence. This phenomenon leads to co-creation of value, which is beneficial to both parties and provides ongoing feedback.

Besides the originality of studying, the behavior of PDCs from the standpoint of two relevant constructs of the business administration literature - co-production and co-creation - this study contributes to the theory by adding to the scanty knowledge provided by Brazilian academic studies of this group of people. For example, unlike Damascena (2013), where the functional characteristics of sensory stimuli involving PDCs were highlighted, sensorial stimuli observed in this study were based on hedonism.

This contribution can in reality be interpreted more broadly than just the literary focus, since the findings combine with those of other researchers (Faria, Ferreira & Carvalho, 2010; Faria & Motta, 2010; Faria & Silva, 2011; Faria, Souto & Rocha, 2011; Damascena, 2013; Mano et al., 2013; Mano, 2014; Silva, Abreu & Gosling, 2015; Mano, Abreu & Silva, 2015) to indicate aspects such as inefficiency or absence of actions by public authorities to facilitate access to services by disabled people, revealing the need to improve public policies in Brazil.

In terms of limitations, this study is based on the means-end chains approach, criticized by many for its operation via the laddering technique, and regarding its predictive validity.

One of the results found act as a suggestion for future studies: the fact that contrary to an assumption generated by common sense, social belonging (one of the LOV values) was not a value expressed by the respondents, even though this belonging may underlie the psychosocial consequence of human condition recovery.

Subsequent research could investigate the extent to which PDCs, in deciding to take advantage of the activities offered by the Praia para Todos project, actually seek "only" an escape from their limitations, providing them with a fleeting feeling of freedom and happiness

REFERENCES

Alén, E., Losada, N. & Domínguez, T. (2012). New opportunities for the tourism market: Senior tourism and accessible tourism. INTECH Open Access Publisher. Retrieved from https://www.intechopen.com/books/visions-for-global-tourism-industry-creating-and-sustaining-competitive-strategies/new-opportunities-for-the-tourism-market-senior-tourism-and-accessible-tourism [ Links ]

Babin, B. J., Darden, W. R. & Griffin, M. (1994). Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(4), 644-656. [ Links ]

Babin, B. J., Hardesty, D. M. & Suter, T. A. (2003). Color and shopping intentions: The intervening effect of price fairness and perceived affect. Journal of Business Research, 56(7), 541-551. [ Links ]

Baker, S. M., Holland, J. & Kaufman-Scarborough, C. (2007). How consumers with disabilities perceive “welcome” in retail servicescapes: A critical incident study. Journal of Services Marketing, 21(3), 160-173.

Baker, S. M., Karrer, H. C. & Veeck, A. (2005). My favorite recipes: Recreating emotions and memories through cooking. Advances in Consumer Research, 32, 402-403. [ Links ]

Baker, S. M., Stephens, D. L., & Hill, R. P. (2002). How can retailers enhance accessibility: Giving consumers with visual impairments a voice in the marketplace. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 9(4), 227-239. [ Links ]

Barbosa, O. T. (2014). Estímulos táteis no ambiente de varejo: Investigando a experiência de consumo de indivíduos com deficiência visual na perspectiva transformativa do consumidor (Dissertação de mestrado não publicada). Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, [ Links ] Brasil.

Beatty, S. E., Kahle, L. R., Homer, P., & Misra, S. (1985). Alternative measurement approaches to consumer values: The list of values and the Rokeach value survey. Psychology & Marketing, 2(3), 181-200. [ Links ]

Bruner, G. C. (1990). Music, mood, and marketing. The Journal of Marketing, 54(4), 94-104. [ Links ]

Burnett, J. J. (1996). What services marketers need to know about the mobility-disabled consumer. Journal of Services Marketing, 10(3), 3-20. [ Links ]

Caru, A. & Cova, B. (2003). A critical approach to experiential consumption: Fighting against the disappearance of the contemplative time. Critical Marketing, 23, 1-16. [ Links ]

Chang, H. J., Hodges, N. & Yurchisin, J. (2014). Consumers with disabilities: A qualitative exploration of clothing selection and use among female college students. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 32(1), 34-48. [ Links ]

Chebat, J. C. & Michon, R. (2003). Impact of ambient odors on mall shoppers’ emotions, cognition, and spending: A test of competitive causal theories. Journal of Business Research, 56(7), 529-539.

Crowley, A. E. (1993). The two-dimensional impact of color on shopping. Marketing Letters, 4(1), 59-69. [ Links ]

Damascena, E. O. (2013). Elementos sensoriais em supermercados: Uma investigação na perspectiva transformativa do consumidor junto a pessoas com deficiência visual (Dissertação de mestrado não publicada). Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, [ Links ] Brasil.

Damascena, E. O., Melo, F. V. S. & Batista, M. M. A. (2012). Deficiência Está no Ambiente de Serviços ou no Consumidor? Discutindo Qualidade na Perspectiva de Clientes com deficiência. V Encontro de Marketing da ANPAD (EMA). Anais... Curitiba (PR), maio.

Faria, M. D. (2011). Pessoas com deficiência visual e consumo em restaurantes: Um estudo utilizando análise conjunta. In XXXV Encontro da Associação Nacional de Pós-Graduação e Pesquisa em Administração (ANPAD). Anais, Rio de Janeiro (RJ), setembro.

Faria, M. D. & Carvalho, J. L. F. S. (2013) Diretrizes para pesquisas com foco em pessoas com deficiência: um estudo bibliométrico em administração. Rev. Ciênc. Admin., 19(1), 35-68, [ Links ] jan./jun.

Faria, M. D., Casotti, L. M. & Carvalho, J. L. F. (2014). O processo de decisão de compra de automóveis adaptados por clientes com deficiência motora. In IV Encontro de Marketing da Anpad (EMA). Anais, Gramado (RS), setembro.

Faria, M. D., Ferreira, D. A. & Carvalho, J. L. F. (2010). O portador de deficiência como consumidor de serviços de lazer extradoméstico. Turismo-Visão e Ação, 12(2), 184-203. [ Links ]

Faria, M. D. & Motta, P. (2010). Restrições ao consumo no lazer turístico: Foco nas pessoas com deficiência visual. In IV Encontro de Marketing da ANPAD (EMA). Anais, Florianópolis (SC).

Faria, M., Silva, J. (2011) Desinteresse em atender as demandas das pessoas com deficiência visual: Foco nas experiências de consumo em restaurantes. In XXXV Encontro da ANPAD (EnANPAD). Anais, Rio de Janeiro (RJ), setembro

Faria, M. D., Silva, J. F. & Ferreira, J. B. (2012). The visually impaired and consumption in restaurants. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 24(5), 721-734. [ Links ]

Faria, M. D., Siqueira, R. P. & Carvalho, J. L. F. S. (2012). Diversidade no varejo, pessoas com deficiências e consumidores não deficientes: Impactos da acessibilidade e da inclusão na intenção de compra. In V Encontro de Marketing da ANPAD (EMA). Anais, Curitiba (PR), maio

Faria, M. D., Souto, S. W. & Rocha, A. M. C. (2011). Posicionamento estratégico de serviços turísticos para pessoas com deficiência: O caso da cidade de Socorro, SP. Caderno Virtual de Turismo, 11(3). [ Links ]

Flick, U. (2009). Introdução à pesquisa qualitativa. Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Ford, R. C. (2014). Prime time: The strategic use of subconscious priming to enhance customer satisfaction. Business Horizons, 57(2), 269-277. [ Links ]

Gentile, C., Spiller, N. & Noci, G. (2007). How to sustain the customer experience: An overview of experience components that co-create value with the customer. European Management Journal, 25(5), 395- 410. [ Links ]

Gill, T. (2008). Convergent products: what functionalities add more value to the base? Journal of Marketing, 72(2), 46-62. [ Links ]

Gil, A. C. (2012). Métodos e técnicas de pesquisa social. São Paulo: Atlas. [ Links ]

Gomes, T., Anne, K., de Azevedo Barbosa, M., & Gomes de Souza, A. (2013). El sistema de oferta de restaurantes de alta gastronomía. Una perspectiva sensorial de las experiencias de consumo. Estudios y Perspectivas em Turismo, 22(2), 336-356. [ Links ]

Goulart, R. (2007). As viagens e o turismo pelas lentes do deficiente físico praticante do esporte adaptado: Um estudo de caso. Dissertação de mestrado não publicada). Universidade de Caxias do Sul, [ Links ] Brasil.

Granger, J. & Kleiner, B. (2003) Benefit programmes for disabled employees. Equal Opportunities International, 22(3), 10-15, [ Links ] 2003.

Grönroos, C. & Ravald, A. (2011). Service as business logic: Implications for value creation and marketing. Journal of Service Management, 22(1), 5-22. [ Links ]

Hernandez, J. M. (2009). Foi bom para você? Uma comparação do valor hedônico de compras feitas em diferentes tipos de varejistas. Revista de Administração Mackenzie, 10(2), 11-30. [ Links ]

Hirschman, E. C., & Holbrook, M. B. (1982). Hedonic consumption: Emerging concepts, methods and propositions. The Journal of Marketing, 46(3), 92-101. [ Links ]

Hogg, G. & Wilson, E. (2004, August). Does he take sugar? The disabled consumer and identity. British Academy of Management Conference Proceedings. St. Andrews, Scotland.

Holbrook, M. B. & Hirschman, E. C. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of consumer research, 9(2), 132-140. [ Links ]

IBGE (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística). Censo Demográfico 2010. Retrieved from ftp://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Censos/Censo_Demografico_2010/Caracteristicas_Gerais_Religiao_Deficiencia/caracteristicas_religiao_deficiencia.pdf [ Links ]

Ikeda, A. A., Campomar, M. C. & Chamie, B. C. (2014). Laddering: Revelando a coleta e interpretação dos dados/Laddering: Unveiling Data Gathering an Interpretation. REMark, 13(4), 49-66.

Instituto Novo Ser. (2016). Retrieved from http://www.novoser.org.br/projetos80.htm. [ Links ]

Jones, P. & Schmidt, R. (2004) Retail employment and disability. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 32(9), 426- 429. [ Links ]

Katz, J. E., & Sugiyama, S. (2006). Mobile phones as fashion statements: evidence from student surveys in the US and Japan. New Media & Society, 8(2), 321-337. [ Links ]

Kaufman, C. (1995). Shop’ til you drop: Tales from a physically challenged shopper. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 12(3), 39-55.

Kaufman-Scarborough, C. (1998). Retailers’ perceptions of the Americans with disabilities act: Suggestions for low-cost, high-impact accommodations for disabled shoppers. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 15(2), 94-110.

Kaufman-Scarborough, C. (2001). Accessible advertising for visually- disabled persons: The case of color-deficient consumers. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18(4), 303-318. [ Links ]

Kellaris, J. J. & Rice, R. C. (1993). The influence of tempo, loudness, and gender of listener on responses to music. Psychology & Marketing, 10(1), 15-29. [ Links ]

Lages, S., & Martins, R. (2006). Turismo inclusivo: A importância da capacitação do profissional de turismo para o atendimento ao deficiente auditivo. Estação Científica, (3), 1-17. [ Links ]

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor- network-theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Locke, E. A. & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting & task performance. Academy of Management Review, 16(2), 212-247 [ Links ]

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American psychologist, 57(9), 705. [ Links ]

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2006). New directions in goal-setting theory. Current Directions In Psychological Science, 15(5), 265-268. [ Links ]

Lucian, R., de Farias, S. A., & Salazar, V. S. (2009). Emoção, ambiente e sabores: A influência do ambiente de serviços na satisfação de consumidores de restaurantes gastronômicos. Revista Acadêmica Observatório de Inovação do Turismo, 3(4), 1-15. [ Links ]

Mano, R. F. (2014). Consumidor com deficiência: implicações de fatores pessoais e contextuais no consumo em redes varejistas de João Pessoa-P. (Dissertação de mestrado não publicada. Universidade Federal da Paraíba, [ Links ] Brasil.

Mano, R. F., Abreu, N. R. & Silva, J. O. (2015) Eu também sou consumidor: Pessoas com deficiência física no varejo hipermercadista da cidade de João Pessoa (PB). Revista Gestão Organizacional, 8(1), 68- 83. [ Links ]

Mano, R. F., de Medeiros, F. G., Diniz, I. S. F. N., & de Abreu, N. R. (2013). Transporte Público e Acessibilidade: um estudo comparativo da qualidade percebida e esperada por usuários com deficiências em João Pessoa. Gepros: Gestão da Produção, Operações e Sistemas, 8(3), 71- 84. [ Links ]

Michon, R., Chebat, J. C. & Turley, L. W. (2005). Mall atmospherics: The interaction effects of the mall environment on shopping behavior. Journal of Business Research, 58(5), 576-583. [ Links ]

Morais, F. R, & Santos, J. B. (2015). Refinando os conceitos de cocriação e coprodução: Resultados de uma crítica da literatura. Revista Economia & Gestão, 15(40), 224-250. [ Links ]

Park, C. (2006). Hedonic and utilitarian values of mobile internet in Korea. International Journal of Mobile Communications, 4(5), 497-508. [ Links ]

Pine, B. J. & Gilmore, J. H. (1999). The experience economy: Work is theatre & every business a stage. Boston: Harvard Business Press. [ Links ]

Prahalad, C. K. & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(3), 5-14. [ Links ]

Reynolds, T. J., & Gutman, J. (1988). Laddering theory, method, analysis, and interpretation. Journal of Advertising Research, 28(1), 11-31. [ Links ]

Reynolds, T. J., & Olson, J. C. (Eds.). (2001). Understanding consumer decision making: The means-end approach to marketing and advertising strategy. Mahwah (NJ): Psychology Press.

Ribeiro, M. A. & Carneiro, R. (2009). A inclusão indesejada: as empresas brasileiras face à lei de cotas para pessoas com deficiência no mercado de trabalho. Organizações & Sociedade, 16(50), 545-564. [ Links ]

Rokeach, M. (1968). Beliefs, attitudes and values: A theory of organization and change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass [ Links ]

Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. New York: The Free Press. [ Links ]

Ruddell, J. L. & Shinew, K. J. (2006). The socialization process for women with physical disabilities: The impact of agents and agencies in the introduction to an elite sport. Journal of Leisure Research, 38(3), 421. [ Links ]

Saeta, B. R. P. & Teixeira, M. L. M. (2008). O lazer na vida da pessoa portadora de deficiência: Uma questão de responsabilidade social e um turismo a ser pensado. Revista de Administração Mackenzie, 2(1).

Sassaki, R. K. (2003). Inclusão no lazer e turismo: Em busca da qualidade de vida. São Paulo: Áurea. [ Links ]

Schmitt, B. (1999). Experiential marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 15(1-3), 53-67. [ Links ]

Schmitt, B. H. (2000). Marketing experimental: Das características e benefícios às experiências. São Paulo: Nobel. [ Links ]

Shi, L., Cole, S. & Chancellor, H. C. (2012). Understanding leisure travel motivations of travelers with acquired mobility impairments. Tourism Management, 33(1), 228-231. [ Links ]

Silva, J. O., Abreu, N. R. & Mano, R. F. (2015). “Ao alcance de quem?!”: Uma reflexão sobre a decisão de compra das pessoas com deficiência física sob a perspectiva da acessibilidade. Revista Economia e Gestão, Belo Horizonte, 15(40), jul./set.

Silva, J., Abreu, N. & Gosling, M. (2015) Ao alcance de quem?!?: Uma reflexão sobre a decisão de compra das pessoas com deficiência física sob a perspectiva da acessibilidade. E&G Economia e Gestão, Belo Horizonte, 15(40), [ Links ] Jul./Set.

Summers, T. A. & Hebert, P. R. (2001). Shedding some light on store atmospherics: Influence of illumination on consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research, 54(2), 145-150. [ Links ]

Vaccaro, V. L., Yucetepe, V., Torres-Baumgarten, G., & Myung-Soo, L. (2009). The impact of atmospheric scent and music-retail consistency on consumers in a retail or service environment. Journal of International Business & Economics, 9(4), 185-196. [ Links ]

Valette-Florence, P. & Rapacchi, B. (1991). Improvements in means-end chain analysis. Journal of Advertising Research, 31(1), 30-45. [ Links ]

Vargo, S. L. & Lusch, R. F. (2004a). The four service marketing myths: remnants of a goods-based, manufacturing model. Journal of Service Research, 6(4), 324-335.

Vargo, S. L. & Lusch, R. F. (2004b). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 1-17.

Woodruff, R. B. & Gardial, S. (1996). Know your customer: New approaches to understanding customer value and satisfaction. New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

Zeithaml, V. A., Parasuraman, A. & Berry, L. L. (1985). Problems and strategies in services marketing. The Journal of Marketing, 33-46. [ Links ]

Zeithaml, V. A., Bitner, M. J.,& Gremler, D. D. (2014). Marketing de serviços: a empresa com foco no cliente. Porto Alegre: Ed. Bookman. [ Links ]

Guest Editors:

· J. A. Campos-Soria

· J. Diéguez-Soto

· M. A. Fernández-Gámez

Received: 11.05.2017

Revisions required: 15.03.2018

Accepted: 10.06.2018