Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.15 no.1 Faro mar. 2019

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2019.150104

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Measuring quality regarding destination marketing: perceptions from local public stakeholders in Portugal

Aferir a qualidade do marketing de destinos: perceções dos stakeholders públicos locais em Portugal

Andreia Filipa Antunes Moura1, Lisete Santos Mendes Mónico2, Maria do Rosário Campos Mira3

1Polytechnic Institute of Coimbra, Coimbra Education School; GOVCOPP-UA; Rua Dom João III - Solum, 3030-329 Coimbra, Portugal, andreiamoura@esec.pt

2University of Coimbra, Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences, Rua do Colégio Novo, 3000-115 Coimbra, Portugal lisete.monico@fpce.uc.pt

3Polytechnic Institute of Coimbra, Coimbra Education School; Rua Dom João III - Solum, 3030-329 Coimbra, Portugal mrmira@esec.pt

ABSTRACT

Motivated by a few studies and international recommendations on tourism quality, we developed a wide-ranging tourism quality scale, adapted to the Portuguese situation. This paper focuses on the development and validation of the marketing subscale to measure the perceptions of local public stakeholders regarding marketing approaches to destination quality improvement. A self-administered survey was applied to a sample of Portuguese municipalities, specifically 134 local public stakeholders, commonly considered local DMOs (Destination Marketing Organizations) and public policy and decision-makers. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were performed to measure quality regarding destination marketing, and two factors were supported: (1) image and promotion; and (2) product differentiation. The instrument demonstrated validity and reliability as a useful measuring tool. The empirical findings highlight the responsibility of local public stakeholders in destination marketing to ensure the quality and competitiveness of tourism, providing many useful insights for future research and practical and theoretical implications.

Keywords: Marketing, DMO, quality, competitiveness, measuring instrument.

RESUMO

Considerando estudos e recomendações internacionais sobre a qualidade em turismo, desenvolveu-se uma escala para a sua avaliação, adaptada à realidade portuguesa. Este artigo foca-se no desenvolvimento e validação da subescala de marketing para medir as percepções dos atores públicos locais em relação às abordagens de marketing para a melhoria da qualidade do destino. Aplicou-se um inquérito a uma amostra de municípios portugueses, especificamente 134, geralmente considerados como as organizações de marketing do destino (DMOs) e principais decisores políticos. Realizaram-se análises fatoriais exploratórias e confirmatórias para aferir a qualidade do marketing de destinos, e dois fatores foram apurados: (1) imagem e promoção; (2) diferenciação do produto. O instrumento demonstrou validade e confiabilidade, sendo uma ferramenta de medida útil. Os resultados destacam a responsabilidade dos stakeholders públicos locais no marketing de destinos para garantir a qualidade e a competitividade do turismo, fornecendo informações úteis para investigações futuras e implicações práticas e teóricas.

Palavras-chave: Marketing, DMO, qualidade, competitividade, instrumento de medida.

1. Introduction

Prior studies support the importance of quality assessment in tourism (Papadimitriou, Apostolopoulou and Kaplanidou, 2015; Lee, Lee and Lee, 2014) as one of the most relevant and simultaneously intangible characteristics of tourism development and competitiveness.

In the last decade, the European Commission (2000, 2003, 2016) has formulated recommendations and measuring tools to assess the quality of destinations’ performance (QUALITEST- based on the concept of Integrated Quality Management of Destinations (IQM) and combines four dimensions: Tourist satisfaction; Satisfaction of tourism professionals; Quality of life of residents; Impact of tourism on natural resources, heritage, among others.), and the United Nations World Tourism Organization - UNWTO (2007) developed suggestions and practical guides, namely “A Practical Guide to Tourism Destination Management", aiming to raise awareness about the importance of quality in tourism management, especially for local stakeholders. The UNWTO in particular, defines the following assessment dimensions: (i) strategy (situation assessment, vision definition, goals and targets); (ii) positioning and brand of destination; (iii) marketing and web-marketing;

(iv) product development; (v) quality of the tourism experience;

(vi) information management and e-business; and, (vii) DMO (UNWTO, 2007). Interestingly, these guidelines are remarkably connected with marketing concerns, implying its interest and significance as a key element for tourism quality and consequently for destination competitiveness.

Based on these orientations, we created a quality assessment scale, organized by subscales: (1) economics, (2) training/ education, (3) products, (4) development and (5) marketing (European Commission, 2016; UNWTO, 2007), to measure the performance of Portuguese destinations. However, it is important to underline that researchers and experts do not agree about the most suitable or adequate factors for quality measurement (Zeithaml, 1988). Therefore, this proposal follows a common recommendation from the international organisations referred to: to be useful and actually employed by local decision-makers and entrepreneurs and to allow comparison of results between destinations.

In this paper, we focus on the marketing subscale, since the literature reveals its transversal and primordial role for the quality and sustainable growth of tourism destinations. Furthermore, as local decision-makers are the basis for creation, promotion and commercialisation of tourism services and products and are then responsible for ensuring their quality, value and identity while stimulating their differentiation (Stylidis, Sit, and Biran, 2016), they were considered the preferred target audience to apply a measuring instrument.

Therefore, our goal is to understand the marketing factors structuring the tourism quality process, from the perspective of the local coordination or management bodies, which in Portugal, are assumed to be municipalities. Therefore, we aim to analyse the psychometric properties of the marketing dimension, which we called “Destination Marketing Strategy Subscale”, considering a broader measuring scale for destinations’ tourism quality. We believe this research will allow Portuguese tourism marketers and others to evaluate their marketing status quo and clarify its factors, as well as to contribute to the development of marketing programs focused on overcoming the tourism sector’s difficulties and needs.

2. Theoretical background

Marketing is essential for the competitiveness of destinations, being consequently a fundamental element of tourism quality. According to Dwyer and Kim (2003) and Ritchie and Crouch (2010), tourism competitiveness is inevitably associated with quality, as it is destinations’ capacity to develop improved overall experiences for tourists in comparison to others (Wong, 2017).

That is, tourists may be attracted and motivated enough to travel to a particular destination, but their ability to consolidate a profitable demand depends, in one hand, on the quality of products and services provided to the customer, and on the other hand, on the information available, accessible communication, effective promotion or overall marketing strategy. In the last decades, mainstream marketing literature has focused on market-oriented strategies as the paramount paradigm for organisations, failing to include different market clusters as destinations (Line and Wang, 2017). In the specific context of destinations, there are several "microclusters" or local stakeholders with powerful means to enhance competitiveness, influencing quality, differentiation and innovation (Garrod and Fyall, 2017).

Hence, recent studies carried out by Line and Wang (2017) suggest destination marketing should extrapolate conventional marketing contexts, as it ideally includes internal and external stakeholders in order to be effective. Bearing in mind that internal stakeholders are Destination Management or Marketing Organizations (DMO) and external stakeholders are local public and private businesses, organisations and communities, it seems crucial to extend traditional customer/competitor-focused marketing research to multi- stakeholder market orientation (MSMO) (Line and Wang, 2017). This MSMO approach may actually embrace the inherent complexity of tourism destinations, as it highlights the organization-wide commitment to value creation, considering the needs of local stakeholders and relevant communication across markets (partners, competitors and consumers) (Line and Wang, 2017).

In many European destinations, local stakeholders, particularly municipalities, play a decisive role in this domain. Municipalities serve as local DMOs and are responsible for their regions’ destination marketing. Interestingly, these “bottom-up” management structures may benefit from stronger social capital among key stakeholders and achieve better marketing results (Garrod and Fyall, 2017). Nevertheless, it must be taken into consideration that DMOs are (a) more than management and/or marketing; (b) not static; and (c) context-dependent (Jørgensen, 2017). Consequently, municipalities hold several different roles in a destination, change dynamically according to the context and needs of the destination and adapt to external relations, policies and practices.

The conception of marketing strategies in these circumstances is exceptionally challenging, as these local DMOs must: (1) be capable of supporting tourism development and quality (Pearce, 2013); (2) be able to market themselves more successfully than their competitors (Wong, 2017); (3) be (re)active to current needs and future trends in the sector (Uşaklıa, Koça and Sönmezb, 2017); and even (4) be aligned with national and international tourism policies; but also (5) be aware of their limitations (Wong, 2017).

Being competitive requires quality, so perceived quality from the marketing management point of view is decisive for strengthening the positioning of tourism destinations, directly influencing their ability to attract and shape customer loyalty (Hallak, Assaker and El-Haddad, 2018). In this context, marketing represents a positive change for destinations, implementing new and innovative orientations and procedures for tourism development and improvement.

The literature emphasises the importance of local DMOs and highlights new organisational and structural trends for destinations that deserve further research, particularly regarding the perception of local public decision-makers who embody DMOs. In Portugal, these structures are supported by municipalities, whose articulated action at the local level creates, promotes and markets tourist services and products in a given region, and ensures quality and identity, leading to differentiation (Stylidis, Sit, and Biran, 2016). Additionally, the analysis of competitive conditions and market positioning have aroused interest in understanding the perceptions of decision-makers about what they value in tourist development, which aspects they attach importance to and how they perceive their involvement in this process (Hallak, Assaker and El-Haddad, 2018).

Measuring and understanding the sensitivity of Portuguese municipalities, acting as DMOs, concerning destination marketing strategy was the main goal of the present research, responding to the challenge raised by several authors and both the European Commission and the UNWTO, which suggest the conception of specific and adapted measuring instruments for different territories, cultures and populations, considering destination quality analysis. This was the motivation supporting the present research, which was based on the previously mentioned instruments and from which we aim to present and discuss the destination marketing strategy.

3. Research design: developing an instrument to evaluate destination marketing quality

3.1 Sample

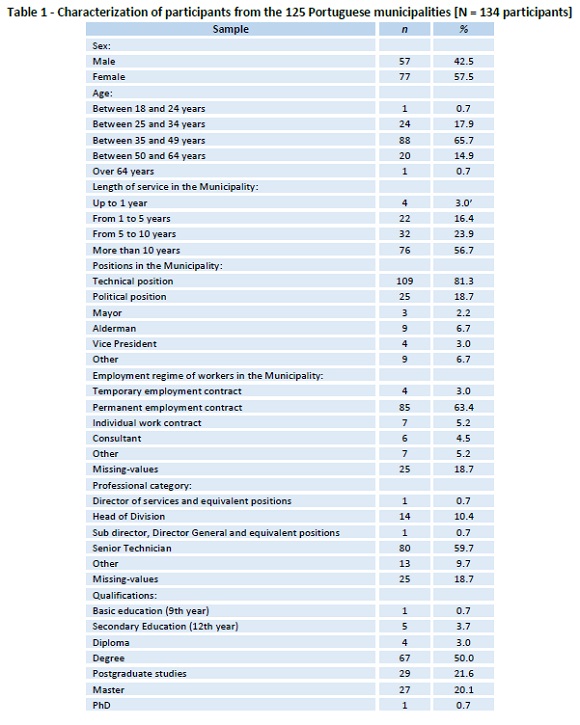

The proposed “Destination Marketing Strategy Subscale” was tested in one hundred and twenty-five municipalities, corresponding to 40.6% of all Portuguese municipalities (N = 308). In these municipalities, 134 participants answered the survey (see Table 1). Most respondents were aged from 35 to 49 years old (65.7%), and there were more females (57.5%) than males (42.5%). The majority are Senior Technicians (59.7%) and above 80% work in the local authority tourism department (81.3%) and have been working there for more than 10 years (56.7%). Most of them hold a permanent position (63.4%) and have higher education qualifications at the degree level (50.0%), followed by a master (20.1%) or a postgraduate degree (21.6%).

3.2 Instruments

The “Destination Marketing Strategy Subscale” was designed considering the European Commission (2000, 2003, 2016) and the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO, 2007, 2010) recommendations.

These international references highlight that satisfactory and memorable tourist experiences depend on the combination of several factors that must be grounded on premises or dimensions of tourism quality, such as (i) economic growth, (ii) human resources training and education, (iii) product enhancement, (iv) integrated development and (v) marketing strategy (European Commission, 2016; UNWTO, 2007). In order to be competitive, destinations need quality, which in turn, is often supported by marketing strategies. Therefore, integrated analysis led to a set of items being introduced in this subscale. Moreover, the presented questionnaire was also supported by the authors’ previous research on the analysis of competitiveness indicators of destinations adapted to the Portuguese situation (Mira, Breda, Moura and Cabral, 2017; Mira, Mónico, Moura and Breda, 2017; Mira, Mónico and Moura, 2017; Mira, Moura and Breda, 2016).

Local public stakeholders were considered as the target population since the literature suggests that tourism competitiveness involves the active participation of stakeholders in the definition of policies, planning and strategic orientation for destinations. For this reason, the importance of assessing the quality of destinations through indicators that reflect the concerns of DMOs at the local level is emphasised. Portuguese municipalities have many of these responsibilities in the territories they manage, including in the tourism sector. Knowing their perception about indicators that assess destination marketing strategy was the foundation for building this questionnaire.

The main procedures in the construction of a measurement scale were followed, including the design and execution of different studies for development and improvement of the questionnaire, which led to the final version of the scale (Urbina, 2014). Likert’s recommendations (1932) in the construction of scales were also followed. Thus, based on the literature review, a set of items that expressed opinions about the marketing dimension of quality in tourism were created, having selected 25 that showed a favourable or unfavourable position (see appendix). Then, a sample described in Table 1 was asked to evaluate each of them using a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The questionnaire also included a set of questions to determine the socio-demographic profile of respondents.

3.3 Procedures

The data used in this study were collected, taking into account ethical issues such as participants’ anonymity and data confidentiality, as well as the avoidance of bias.

An online version of the questionnaire was built using Google Forms and sent by e-mail to all Portuguese municipalities. The average time of response was 12 minutes. Control of the responses was carried out monthly through the ‘Municipality’ variable, sending a reminder to the municipalities that had not yet responded and stressing the importance of their participation in the study. The questionnaire had the instruction that it should be filled in by municipal representatives with responsibilities in tourism. Information on the objectives of the study, completion instructions, and the voluntary and anonymous nature of participation and the guarantee of data confidentiality were also included at the beginning of the questionnaire.

3.4 Data analysis

All the analyses were completed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics, version 22 (IBM Corp., 2013) software, and IBM® SPSS® AMOS, version 22 (IBM Corp., 2013) for Windows operative system. Outliers were analysed according to the Mahalanobis squared distance (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2013), with no relevant values being found. The normality of the variables was assessed by the coefficients of skewness (Sk) and kurtosis (Ku), showing that no variable presented values violating normal distribution, namely |Sk|< 2 and |Ku| < 3.

Exploratory factor analysis was performed using SPSS by PCA - Principal Component Analysis. The PCA assumptions were tested through the sample size (ratio of 5 subjects per item and at least 100 participants; Urbina, 2014), the normality and linearity of the variables, factoriability of R, and sample adequacy (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2013). Since we intend to retain as many independent factors as possible, we chose the VARIMAX rotation method with Kaiser’s normalisation.

Confirmatory factorial analysis was performed with AMOS (v. 22.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL; Arbuckle, 2013), using the maximum likelihood estimation method (Jöreskog and Sörbom, 2004). Goodness of fit was analysed by the indexes of NFI (Normed of fit index; good fit > .80; Schumacker and Lomax, 2010), SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual; appropriate fit<.08; Schumacker and Lomax, 2010), TLI (Tucker-Lewis Index - TLI; appropriate fit > .90; Kline 2011), CFI (Comparative fit index; good fit > .90; Hair, Anderson, Tatham, and Black, 2004), CMIN/DF (good fit < 2; Schumacker and Lomax, 2010), and RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; good fit < .05; Kline 2011). The fit of the model was improved by modification indices (MI; Urbina, 2014), leading to a correlation of the residual variability between variables with the highest MI. We followed Arbuckle’s proposal (2013), which consists of analysing the MIs by their statistical significance (α < 0.05).

Reliability was calculated by Cronbach's alpha. Reliability coefficients higher than .70 were considered acceptable for convergence and reliability (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, and Black, 2004). In general, the value of .80 was taken as a good reliability indicator (Urbina, 2014). The composite reliability and the average variance extracted for each factor were evaluated as described in Schumacker and Lomax (2010).

4. Results

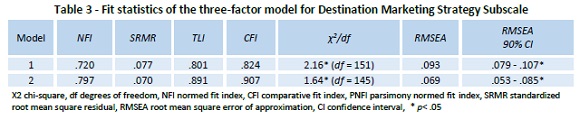

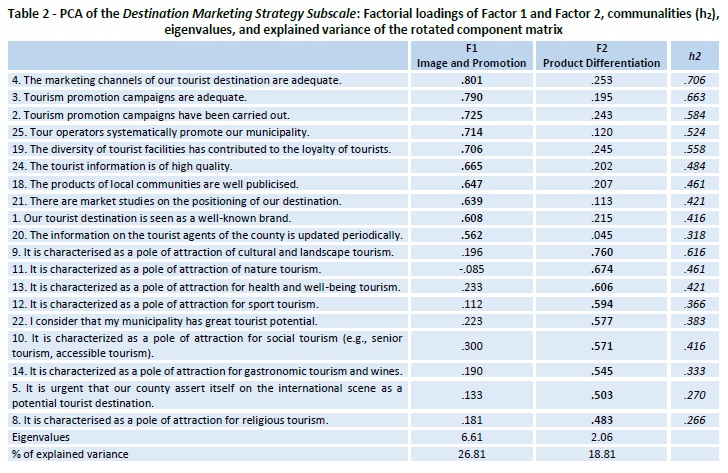

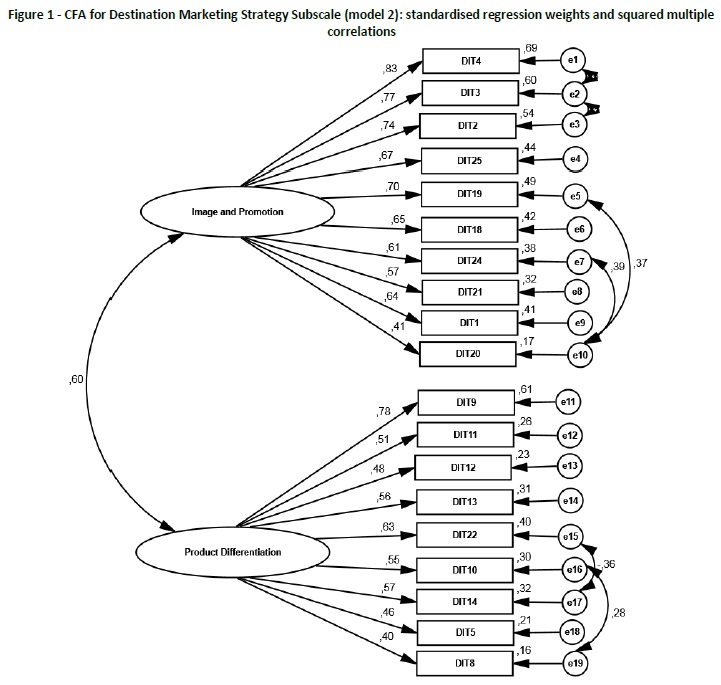

Measurements of constructs in the framework were subject to exploratory factor analysis because the scale items were either developed or adapted from previous studies. Principal axis factoring was used as the extraction method to maximise the distinctiveness of factors. Table 2 shows the psychometric properties of each variable in the measurement model. As a combination of the measurement and path models, the structural model was examined using confirmatory factor analysis. The goodness-of-fit statistics indicated that the structural model fits the data well (see Table 3). The structural model with path estimates is shown in Figure 1

(clique para ampliar ! click to enlarge)

(clique para ampliar ! click to enlarge)

4.1 Exploratory factor analysis

The requirements necessary for reliable interpretation of PCA were analysed. Since the questionnaire we used has 25 items, the ratio found was 134 subjects/25 items = 5.36 subjects/item, which enables, a priori, reliable use of PCA (Urbina, 2014). Additionally, the intercorrelation matrix differed from the identity matrix, since Bartlett’s test showed an X2(300) = 1466.23, p<.001, and the sampling was adequate - the value obtained for the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure was .852, higher than the required value of .70.

According to the eigenvalue criterion over one, a six-factor solution emerged, responsible for 63.73% of the total variance. However, this factorial solution was not interpretable. Moreover, factorial loadings (s) showed the following items as less representative of each factor (s<.50; Tabachnick and Fidell, 2013) or less discriminative (factorial loadings similar in two or more factors):6 - ‘It is characterised as a pole of attraction of scientific events’; 7 - ‘It is characterised as a pole of business attraction’; 15 - ‘It is characterised as a pole of attraction of nautical tourism’; 16 - ‘It is preferentially directed to the international market’; 17 - ‘It is preferentially directed to the national market’; and 23 - ‘I consider that tourism in my county has much quality’. Another criterion for excluding these items was the improvement of the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient after their elimination.

With the remaining 19 items, the scree plot suggested a solution of two main factors, responsible for 45.62% of the total variance, with the first factor explaining 26.81% of the total variance, and the second factor 18.81%. Factorial loadings (s) are higher than .50 (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2013) in all items, except for item 8, with a factorial loading of .48 in Factor 2 (see Table 2). However, this score is acceptable considering the sample size (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, and Black, 2004), since our sample has a total N between 120 (s> .50) and 150 (s > .45; Hair et al., 2004, p. 107).

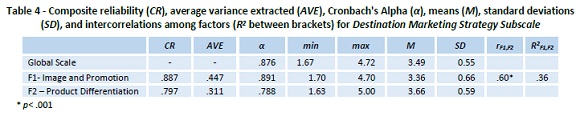

As seen in Table 2, Factor 1 is composed of 10 items related to destination branding and positioning, promotional activities and tourist information, so this factor was designated as ‘Image and Promotion’. Factor 2 was named ‘Product Differentiation’ since it includes 9 items corresponding to destination potential, uniqueness and poles of attractiveness.

4.2 Confirmatory factor analysis

CFA was performed in order to test the fit of the factorial solution found by EFA (see fit indices for model 1 in Table 3, no error terms correlated). For model 1, only the SRMR index showed an acceptable fit. Based on the highest modification indices inside each factor, error terms were correlated in model 2, as shown in Figure 1. This covariation indicates non-random measurement errors, which may result from items’ similarities (e.g., semantic redundancy), sequential positioning in the scale and the specific characteristics of respondents (Jöreskog and Sörbom, 2004). Model 2 showed an acceptable fit (see Table 3, model 2).

Standardised regression weights and squared multiple correlations of model 2 are shown in Figure 1. Standardised regression weights ranged from .40 to .83 and squared multiple correlations from 16% to 69%.

The Cronbach alpha for the global scale and Factor 1 are good, since they were above .80 (see Table 4), and acceptable for factor 2, since it is higher than .70. Composite reliability was also good, since higher than .70. Concerning the average variance extracted (AVE), only factor 1 exceeds the cut-off value of .40, showing an acceptable convergent validity (Diamantopoulos and Siguaw, 2000). The mean score for the Global scale showed a value slightly above the mid-point of the Likert scale options. The scores for both factors were similar, F2- Product Differentiation having the highest score.

5. Discussion and implications

The results indicate that ‘image and promotion’ (F1) and ‘product differentiation’ (F2) are the most important dimensions of destination marketing strategies, for the local public stakeholders in Portugal.

Considering F1, the research findings revealed that destination image plays a central role in a marketing strategy definition and that this is built on brand, positioning and tourist facilities which contribute to customer loyalty. These outcomes agree with the studies by Dwyer and Kim (2003) and Yangyang, Haywantee, Felix and Shanfei (2017), which support destination environment, services and facilities as the critical features for destination image. Yangyang et al. (2017) add that destination image is the combination of the opinions, thoughts and perceptions an individual has of a specific setting, which is intrinsically blended with branding and positioning. Additionally, Pike (2017) concluded that destination branding and positioning is even more difficult these days, given the challenge of reaching the minds of busy consumers and the great difficulty of changing individuals’ perceptions, advising destination marketers to (i) preserve determinant attraction poles for which the destination is positively perceived, and (ii) act strongly and consistently in every marketing communication channel in the long term. In this context, the results revealed that local public stakeholders in Portugal agree with these latest trends, settling destination image with destination promotion, which in turn, relates to marketing communication channels, namely promotional campaigns and publicity, in line with tourism distribution channels such as tour operators and tourist information.

Regarding F2, the results accentuate the relevance of exceptionality and preserving authenticity in tourism destinations since Portuguese local tourism decision-makers underline as the main foundation for the marketing strategy the territory’s potential and attractiveness, precisely through particular added value resources that may be transformed into tourism products such as culture, landscape, nature, health and well-being, sport, gastronomy, wine, religion and social care or hospitality. Corroborating these findings Abou-Shouk, Zoair, El- Barbary and Hewedi (2018)claimed the effort of destination marketing strategy should include both the setting and how visitors create and form their experiences accordingly. In addition, an intelligent and vibrant destination marketing strategy should be multidimensional and segment-related (Dolnicar and Grün, 2017). Given the existence of a noteworthy connection between product and destination perceptions, De Nisco, Papadopoulos and Elliot (2017) produced solid evidence that destinations “characterized by a strong international reputation for their products (especially products connected with significant tourism features, like food, fashion, or crafts) may use their reputation as producers for enhancing and differentiating their international image as a tourism destination” (p. 438).

Another important aspect of the results obtained is related to the reasonable correlation between Factors 1 and 2, which explain much of the total variance (45.62%) (see Figure 1). For this reason, it can be inferred that, from the respondents’ perspective, tourism quality depends on the destination marketing strategy, which is primarily determined by the way branding and positioning, promotional activities and tourist information are enhanced considering the destination’s potential, uniqueness and attractiveness.

5.1 Theoretical implications

This study improves tourism marketing understanding and offers potential advances since it proposes an assessment instrument to measure destination quality regarding the marketing strategy dimension. Few studies, if any, have explored destination quality in its various dimensions and very few have suggested measurement instruments in this context. Indeed, previous research over the past 40 years has revealed that tourism marketing encourages tourists to increase their length of stay, adjust their activity preferences, and even raise expenditure rates (Choe, Stienmetz, and Fesenmaier, 2017), but stakeholders and DMOs’ awareness of its importance fail to be explored and documented.

Thus, this study offers deeper insight into the perceptions of local public stakeholders in Portugal, namely local DMOs, about destinations’ marketing strategy. It provides a clearer comprehension of their marketing standpoint, allowing for future international comparative analysis, longitudinal investigation and improvement planning and sustainable policy-making support.

By exploring this particular dimension of the overall tourism quality scale, adapted to the Portuguese situation, this study offers a new perspective of looking at ‘image and promotion’ and ‘product differentiation’, when thinking about destination quality.

5.2 Practical and managerial implications

This study contains a methodological framework for the operationalisation of organisational self-assessment, enabling DMOs, stakeholders and other local tourism managers or marketers to identify marketing strategy factors that may be critical for the success and development of tourism destinations, leading to conscious decision-making on actions in line with updated feedback.

The findings provide directions for public policy-makers involved in destination marketing in two primary avenues: destination branding and positioning, promotional activities and tourist information (F1) and destination potential, uniqueness and poles of attractiveness (F2). Both agree with contemporary trends that tourists are increasingly concerned with authentic experiences through genuine feelings and emotional achievements (Jiang, Ramkissoon, Mavondo and Feng, 2017), which may be enhanced by accurate marketing strategies.

Another important aspect emerging from the research findings and corroborating the literature is that destination marketing should pursue internationalisation and therefore competitiveness (see item 5. “It is urgent that our county assert itself on the international scene as a potential tourist destination”).

In this framework, DMOs are a destination’s guarantee of quality and competitiveness, but reduced public sector funding and increased dependence on commercial income to support core activities (Li, Robinson and Oriade, 2017) appear as important constraints for marketing tasks’ operationalisation. Conveniently, at the same time, digital tools emerge as an effective low-cost marketing instrument with worldwide reach (Uşaklıa, Koça and Sönmezb, 2017), making it possible to develop marketing activities even on a limited budget. Moreover, the consumer revolution which has led to the increase of non-conventional tourism products and services and the rise of more informed travellers with higher quality standards and open access to mobile technology has provided significant opportunities for DMO functions and commitments (Li, Robinson and Oriade, 2017).

The effect of the internet, social media and technological mobility on information and product differentiation, communication and consumer attraction, and also on networking and partner engagement, requires new marketing approaches and practice. In this vein, DMOs should progressively reflect the possibility of both “co-creation” and “prosumption” (Li, Robinson and Oriade, 2017). While Binkhorst and Dekker (2009, p. 315) suggest co-creation is “the interaction of an individual at a specific place and time and within the context of a specific act”, perceiving the tourist as part of the process of designing the tourist experience, Xie, Bagozzi and Troye (2008, p110) define prosumption (within tourism) as “value creation activities undertaken by the consumer that result in the production of products they eventually consume and that become their consumption experiences”, underlining the combination of the processes of production and consumption.

Subsequently, the traditional role of DMOs as data sources and information centres should predictably change into new specialised services consistent with new communication tools, transcending physical and time boundaries (Li, Robinson and Oriade, 2017).

The research findings also underline that tourism authorities and other destination stakeholders should operate collectively (Jiang et al, 2017), but their sensitivity and awareness of this need, and particularly of what it involves, is still limited and occasional. Therefore, local public stakeholders and other destination managers are advised to establish partnerships and collaborative networks, especially in the context of interactive marketing planning processes for destinations.

6. Conclusions

According to Silva and Correia (2017), competition is increasing in tourism marketing and retaining strategies are critical for sustainable destination development. So it is urgent to have reliable instruments to monitor and measure the quality of destinations since this is the central hub for competitiveness and sustainability. Marketing is one of the most important dimensions of quality and its importance is growing in the context of destination retaining policies.

In conclusion, this study and the data collected meet this evolving challenge, suggesting an assessment scale for better understanding of destination marketing strategy from the perspective of local public stakeholders in Portugal, generally presumed to be local DMOs.

In short, this study enriches the tourism and marketing research fields since it indicates that destination quality depends on the originality and diversity of tourism products and services, defining competitive advantages, and these express a destination’s image and promotion, standing out as the foundations of destination marketing strategies.

Finally, we draw attention to some limitations of this study. First of all, there is a need to continue this research, with different and larger samples. Secondly, the questionnaires were sent by email, which made it challenging to answer possible doubts. Thirdly, this is a cross-sectional study, which means the results are constrained to a specific time of data collecting. Lastly, another limitation is the data-collection method - the self- administered questionnaire; despite the inherent advantages of anonymity, the possibility of obtaining a broad scenario of the research area and less respondent "reactivity", the problem of the validity of the conclusions arises, more precisely, the establishment of conditions that aim to guarantee the internal validity of the investigation (Alferes, 2012).

For these reasons, we suggest applying the proposed instrument in other international contexts and longitudinally, determining temporal evolutions or similarities and differences between destinations. Furthermore, concerning extending this field of expertise, one of the priorities should be to increase research about the marketing dimension strategy and other quality dimensions such as “development”, “economics”, “human resources” and “product”.

REFERENCES

Abou-Shouk, M.A., Zoair, N., El-Barbary, M.N., Hewedi, M.M. (2018). Sense of place relationship with tourist satisfaction and intentional revisit: Evidence from Egypt. International Journal of Tourism Research, 20(2), 172-181. [ Links ]

Alferes, V. R. (2012).Methods of randomization in experimental design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Arbuckle, J. L. (2013). Amos 22 user’s guide. Chicago, IL: SPSS.

Binkhorst, E., and Dekker, T. (2009). Agenda for co-creation tourism experience research. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 18(2-3), 311-327.

Choe, Y., Stienmetz, J. L., and Fesenmaier, D. R. (2017). Measuring destination marketing: Comparing four models of advertising conversion. Journal of Travel Research, 56(2), 143 -157. doi: 10.1177/0047287516639161

De Nisco, A., Papadopoulos, N., and Elliot, S. (2017). From international travelling consumer to place ambassador: Connecting place image to tourism satisfaction and post-visit intentions. International Marketing Review, 34(3), 425-44. doi: 10.1108/IMR-08-2015-0180

Diamantopoulos, A., and Siguaw, J. A. (2000). Introducing to Lisrel: a guide for the uninitiated. London: Sage.

Dolnicar, S., andGrün, B. (2017). In a galaxy far, far away: Market yourself differently. Journal of Travel Research, 56(5), 593 -598. doi: 10.1177/0047287516633529

Dwyer, L., and Kim, C. (2003). Destination competitiveness: Determinants and indicators. Current Issues in Tourism, 6(5), 369-414.

European Commission (2000). For urban tourism quality: Integrated quality management (IQM) for urban destinations. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. [ Links ]

European Commission (2003). A manual for evaluating the quality performance of tourist destinations and services. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. [ Links ]

European Commission (2016). The European tourism indicator system: ETIS toolkit for sustainable destination management. Accessed in April 2016, http://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/tourism/offer/sustainable/indicators/index_en.htm [ Links ]

Garrod, B., and Fyall, A. (2017). Collaborative destination marketing at the local level: Benefits bundling and the changing role of the local tourism association. Current Issues in Tourism, 20 (7), 668-690. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2016.1165657

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R.E., Thatam, R., and Black, W. C. (2004). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). New York: Prentice Hall.

Hallak, R., Assaker, G., El-Haddad, R. (2018). Re-examining the relationships among perceived quality, value, satisfaction, and destination loyalty: A higher-order structural model. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 24(2), 118-135. [ Links ]

Jiang, Y; Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F. T. and Feng, S. (2017). Authenticity: The link between destination image and place attachment. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 26(2), 105-124. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2016.1185988

Jöreskog, K. G., and Sörbom, D. (2004). LISREL 8.7 for Windows [Computer Software]. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc.

Jørgensen, M. T. (2017). Developing a holistic framework for analysis of destination management and/or marketing organizations: Six Danish destinations. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 34(5), 624-635. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2016.1209152 [ Links ]

Kline, R. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

Lee, B. K., Lee, C. K., and Lee, J. (2014). Dynamic nature of destination image and influence of tourist overall satisfaction on image modification. Journal of Travel Research, 53(2), 239-51.

Li, S. C. H., Robinson, P., and Oriade, A. (2017). Destination marketing: The use of technology since the millennium. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management,6, 95-102.

Line, N. D., and Wang Y. (2017a). A multi-stakeholder market oriented approach to destination marketing. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 6, 84-93.

Mira, M. R., Breda, Z., Moura, A., and Cabral, M. (2017). O papel das DMO na gestão dos destinos turísticos: Abordagem conceptual (1999- 2014). Observatório de Inovação do Turismo - Revista Acadêmica, 11(1), 53-70.

Mira, M. R., Mónico, L., and Moura, A. (2017). Qualidade dos recursos humanos em turismo: A opinião dos decisores públicos portugueses. Revista Psicologia: Organizações e Trabalho, 17(4), 1-10. doi: 10.17652/rpot/2017.4.13746

Mira, M. R., Moura, A., and Breda, Z. (2016). Destination competitiveness and competitiveness indicators: Illustration of the Portuguese reality. TÉKHNE - Review of Applied Management Studies, 14, 90-103. URL :http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tekhne.2016.06.002

Mira, M. R.; Mónico, L.; Moura, A. and Breda, Z. (2017). Qualidade do desenvolvimento turístico na perspetiva dos decisores públicos locais Portugueses: Uma proposta de medida. Revista Turismo & Desenvolvimento, 27/28(1), 1675 - 1687. ISSN: 2182-1453,

Papadimitriou, D., Apostolopoulou, A., and Kaplanidou, K. (2015). Destination personality, affective image and behavioural intentions in domestic urban tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 54(3), 302-315.

Pearce, D.G. (2013). Toward an integrative conceptual framework of destinations. Journal of Travel Research, 53(2) 141-153. [ Links ]

Pike, S. (2017). Destination positioning and temporality: Tracking relative strengths and weaknesses over time. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 31, 126-133. [ Links ]

Ritchie, J. R., and Crouch, G. (2010). A model of destination competitiveness/sustainability: Brazilian perspectives. Revista de Administração Pública, 44(5), 1049-1066.

Schumacker, R. E., and Lomax, R. G. (2010). A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence ErlbaumAssociates.

Silva, R., and Correia, A. (2017). Places and tourists: Ties that reinforce behavioural intentions. Anatolia, 28(1), 14-30. doi: 10.1080/13032917.2016.1240093

Stylidis, D., Sit, J., and Biran, A. (2016). An exploratory study of residents’ perception of place image: The case of Kavala. Journal of Travel Research, 55(5), 659-674. doi: 10.1177/0047287514563163

Tabachnick, B. G., and Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.) New Jersey: Pearson Education.

UNWTO (2007). A practical guide to tourism destination management. Madrid: World Tourism Organization. [ Links ]

UNWTO (2010). Survey on destination governance: Evaluation report. Madrid, World Tourism Organization. [ Links ]

Urbina, S. (2014). Essentials of psychological testing. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Uşaklıa, A., Koça, B., and Sönmezb, S. (2017). How 'social' are destinations? Examining European DMO social media usage. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 6, 136-149.

Wong, P. P. W. (2017). Competitiveness of Malaysian destinations and its influence on destination loyalty. Anatolia, 28(2), 250-262. doi: 10.1080/13032917.2017.1315825 [ Links ]

Xie, C.,Bagozzi, R. P. and Troye, S. (2008).Trying to prosume: Toward a theory of consumers as co-creators of value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 109-122.

Yangyang, J., Haywantee R., Felix T. M., and Shanfei F. (2017). Authenticity: The link between destination image and place attachment. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 26(2), 105-124. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2016.1185988

Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52, 2-22. [ Links ]

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the participation of Portuguese public decision- makers at the local level, who contributed to this research with their experience and knowledge.

Received: 15.05. 2018

Revisions required: 28.10.2018

Accepted: 15.12.2018