Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.15 no.1 Faro mar. 2019

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2019.150107

MANAGEMENT: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Psychological coaching as a driver to enhance the networking capabilities of young entrepreneurs

Coaching psicológico como impulsionador para melhorar as capacidades de networking de jovens empreendedores

Ana Galvão1, Marco Pinheiro2

1Polytechnic Institute of Bragança, Health Sciences Research Unit: Nursing (UICISA: E), School of Health, Bragança, Portugal, anagalvao@ipb.pt

2Polytechnic Institute of Bragança, Partner B’TEN Consultants, mpinheiro@ipb.pt

ABSTRACT

According to the Global Entrepreneurship Index 2018, Portuguese entrepreneurship is suboptimal, namely due to the low capacity of networking by Portuguese entrepreneurs. As such, this research focuses on the psychological and personality traits that may be the origin of this suboptimal performance. To carry out the research, 331 young adults participated by answering a questionnaire composed out of three parts: a sociodemographic part; the Portuguese Entrepreneurial Psychological Traits Inventory (PEPTI); and the Big Five Inventory (BFI-44). The results show that young entrepreneurs have higher scores on the PEPTI and four of the five dimensions of the BFI-44. However, the differences in Agreeableness are not statistically significant, possibly evidencing one of the reasons for suboptimal networking skills. As networking capabilities are important for successful entrepreneurship, we propose the development of a psychological coaching programme for young entrepreneurs with the objective to enhance several soft-skills that improve networking capabilities.

Keywords: Young entrepreneurs, networking, psychological coaching, personality traits.

RESUMO

Segundo o Global Entrepreneurship Index 2018, o empreendedorismo português é abaixo do ótimo, nomeadamente devido à baixa capacidade de networking dos empreendedores portugueses. Como tal, esta investigação foca-se nos traços psicológicos e de personalidade que podem ser a origem desse desempenho abaixo do ótimo. Participaram 331 jovens adultos para realizar a investigação, respondendo a um questionário composto por três partes: uma parte sociodemográfica; o Inventário Português de Características Psicológicas Empresariais (IPCPE); e o Big Five Inventory (BFI-44). Os resultados mostram que os jovens empreendedores têm pontuações mais altas no IPCPE e em quatro das cinco dimensões do BFI-44. No entanto, as diferenças em agradabilidade não são estatisticamente significativas, possivelmente evidenciando uma das razões para competências de networking abaixo do ótimo. Como as capacidades de networking são importantes para o empreendedorismo de sucesso, propomos o desenvolvimento de um programa de coaching psicológico para jovens empreendedores com o objetivo de impulsionr várias competências sociais que melhoram as capacidades de networking.

Palavras-chave: Jovens empreendedores, networking, coaching psicológico, traços de personalidade.

1. Introduction and Objectives

Entrepreneurship has become a common word in the European and also Portuguese vocabulary, much driven by the pressure that the crisis imposed on the labour market, therefore creating a need for self-employment alternatives (Beck, Demirguc-Kunt, Laeven, & Levine, 2008; Carree & Thurik, 2010; Galvão & Pinheiro, 2017). Taking the Portuguese case as an example, the more recent years have been a good example of the collective effort that has been put in the development of conditions to support entrepreneurial initiatives through either hard skill training programmes, acceleration programmes, subsidies and even public venture capital funds. However, little or no evidence is found about support on the soft skill sides, namely enhancing certain personality or psychological traits.

Notwithstanding the fact that several studies have been performed about entrepreneurial personality or psychological traits among students (Marques, 2016; Rego, 2000) only a few studies exist in Portugal about the traits of entrepreneurs or established business owners that have already surpassed the pre-seed and seed capital phases (Galvão & Pinheiro, 2017). However, the need for enhancement of soft skills, specifically in networking capabilities, is necessary and a clear indication of this need is given in several reports, particularly in the Global Entrepreneurship Index 2018 (Ács, Szerb, & Lloyd, 2017). In this report, where Portugal ranks 31st among the 137 countries included in the research, the weakest area of entrepreneurship in Portugal is pointed out to be networking, with a score of 33 out of 100.

One of the more recent fields of study, in what concerns entrepreneurship and respective psychological or personality traits and how to enhance soft-skills, centres its approach on (psychological) coaching as a driver for positive change and improvement of several of the required skills for successful entrepreneurship (Davis, Hall, & Mayer, 2016; Martins, Galvão, & Pinheiro, 2017; Premand, Brodmann, Almeida, Grun, & Barouni, 2016). As these studies point out, coaching, and psychological coaching in particular help entrepreneurs to enhance positively certain traits that may on their turn enhance their entrepreneurial skills, namely in what concerns networking (Shu, Ren, & Zheng, 2018).

Other research, points out that some of the Big Five personality traits (John, Donahue, & Kentle, 1991; John & Srivastava, 1999), are related to (social) networking capabilities, namely Extroversion, Agreeableness and Openness to Experience (Wolff & Kim, 2012).

Given the aforementioned and the importance that an excellent entrepreneurial development has for the economic growth of a country, took us to the conclusion that more research on these topics was urgently needed in Portugal, hence the reason for carrying out this study.

As such, the main objective of this study was to research if young entrepreneurs show different psychological or personality traits when compared to their non-entrepreneur peers and if the differences, in case they existed, could evidence differences in networking skills, and simultaneously propose a psychological coaching programme for higher education students that can potentiate networking skills.

It’s our intention that this study contributes to understanding how Portuguese entrepreneurs may improve their (social) networking skills, hence improving the overall performance in this global and extremely competitive landscape.

2. Literature Review

In recent years an increasing number of studies have analysed the importance of networking on entrepreneurship. Although almost all these studies conclude that there is indeed a relationship between networking and successful entrepreneurship, only a few studies try to find the exact relationships as well as to quantify these relationships.

The impact of networking on organisations dates back to the ‘30s of the last century (Jack, 2010), but only more recently research has increased considerably focussing not only on organisations but also on the relationships between individuals and groups and organisations (Parkhe, Wasserman, & Ralston, 2006). Several studies point out that there is indeed a relationship between networks or networking and the manner organisations are managed, sustained, or even developed, thus creating a central study subject of researchers (Nelson, 2001; Nohria & Eccles, 1992).

The positive impact of networking on business development is becoming increasingly consensual, as can be concluded, for instance, through the reason why for certain authors, networking makes us have to rethink the way businesses are shaped and grow (Parkhe et al., 2006) but also given that it is one of the fourteen indicators to measure the entrepreneurship ranking of countries (Ács et al., 2017). Other studies point out that there is a positive correlation between networking and company performance (Lee & Tsang, 2001).

But networking does not only derive from rational or learnable skills. It involves, besides business knowledge, a very strong component of socio-psychological traits and aspects (Valkokari & Helander, 2007). Also, if we take into account Small and Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs) or start-ups an evenly unneglectable aspect, is the fact that those traits are intrinsic to the entrepreneur and that a SMEs or start-up’s network many times will coincide with the founders’ personal networks (Biggiero, 2001).

Several studies about entrepreneurial characteristics, combined with the Big Five personality traits, point out that the traits that influence networking capabilities of entrepreneurs the most are extroversion and agreeableness and these traits are proven to have a positive effect on entrepreneurship and venture growth.

The personality trait Agreeableness gives the entrepreneur several advantages when it comes to networking capabilities. This trait enhances the cooperativeness of the entrepreneur (Denissen & Penke, 2008), enhances emphatic interactions (Nettle, 2006), and helps the entrepreneur to manage conflicts in a more consensual manner (Jensen-Campbell, Gleason, Adams, & Malcolm, 2003). Shipilov, Labianca, Kalnysh, and Kalnysh (2014) consider that agreeableness helps the entrepreneur to not see networking as something with a high maintenance and opportunity cost, but rather something that he or she does intrinsically.

Extroversion, the second personality trait extensively presented as vital for networking capabilities, acts through the natural willingness of extroverts to want to be surrounded by others (Lee & Tsang, 2001). Extroverts socialise more in several situations, from creating visibility in the work-place up to job- seeking activities (Forret & Dougherty, 2001; Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000).

Psychological Coaching as a Driver Towards Change

Higher education students face new challenges in a society that is turning more and more towards knowledge and innovation capacity, thus posing new requirements on education. The modern world seeks entrepreneurial and innovative skills in its next generation of workforce and handling these skills will be a major differentiation factor for students when entering the labour market. Therefore, higher education organisations need to adapt to this and also to a growing multicultural environment where acquired skills will be put to test more often and in a totally different manner than happened until recently. New tools for educating students for these new requirements are of paramount importance as are the different approaches to education where not only hard-skills are necessary but also, and in some cases even more important, soft-skills.

At present times it is consensual that entrepreneurship training at higher education institutions is crucial for economic growth and wealth creation (Shane, 2004). Simultaneously, higher education institutions are adapting to this new need and are creating academic entrepreneurial centres, many times together with incubators and accelerators, and are also motivating students, but also faculty and researchers, to take their ideas and discoveries to the market through a manifold of possibilities, ranging from patents to spin-offs (Wood, 2009).

Studies also conclude that taking up entrepreneurial subjects in course curricula in many study areas, increases the students’ willingness to create their own businesses (Shinnar, Pruett, & Toney, 2009) and that it changes the students’ attitudes towards entrepreneurship.

3. Methodology

3.1 Participants

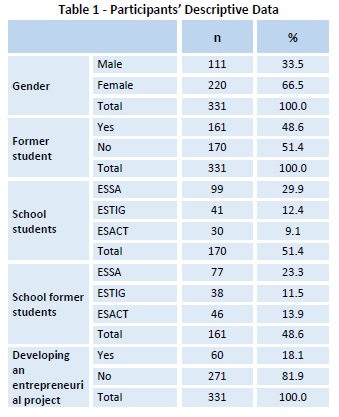

As described in Table 1 the sample for this research is composed out of students (n=170; 51.4%) and former students (n=161; 48.6%) of the Instituto Politécnico de Bragança (IPB), a polytechnic higher education institute in the North-eastern region of Portugal, with a total population of over 7000 students, divided among a variety of undergraduate and master courses in five different schools, covering distinct areas like, for instance, health, technology, management, education and agriculture.

As also can be seen from Table, the majority of the sample is female (n=220; 66.5%), being the most represented school the higher school of health (ESSA), both within the present students (n=99; 29.9%) as well as former students (n=77; 23.3%). Of the total sample, 60 respondents (18.1%) are developing an entrepreneurial project.

3.2 Instruments

The data for this research has been collected through the use of a questionnaire, delivered to respondents both on paper as well as through an online questionnaire, the latter particularly for former students who were harder to reach. Participating in the research was entirely voluntary, and all questionnaires are anonymous. Data collection took place between November 2017 and April 2018.

The questionnaire was divided into three parts, being the first part composed out of questions to gather socio-demographic information, such as gender, age, course (present, or past in the case of former students), if the respondent was working on an entrepreneurial project, and other information about the respondents. The second part of the questionnaire presented the Portuguese Entrepreneurial Psychological Traits Inventory (Galvão & Pinheiro, 2017) and the third part the Big Five Inventory-44 (John et al., 1991).

Portuguese Entrepreneurial Psychological Traits Inventory (PEPTI)

The Portuguese Entrepreneurial Psychological Traits Inventory (PEPTI), developed, tested and validated by Galvão and Pinheiro (2017), is a 16 items, self-report inventory measuring three entrepreneurial traits, specially adapted to the Portuguese language and culture. All items are answered on a 6-point Likert-type of scale, being the 6 points used to avoid central- point answers. Each of the dimensions is scored as the average score of its respective items.

The development of the inventory took place between 2015 and 2017 and resulted from research involving 486 individuals, divided into two samples, of which, in total, 189 were established business owners. The inventory, through structural equation modelling on both samples, showed excellent model fit indices (RMSEA=.036/.052; CFI=.971/.951; TLI=.966/.942).

The inventory measures three entrepreneurial traits, defined in linguistic terms according to the opinion of a test group of business owners. These three entrepreneurial traits are Pragmatism, with ten items, and which is according to the Portuguese entrepreneurs a must for success; Comfort (as in “Need for Comfort”), with three items, which contrary to, for instance, Anglo-Saxon entrepreneurs, is a real need for Portuguese business owners; and Acceptance (as in “Need to be accepted by others”), also with 3 items, which represent the recognition in society, which Portuguese business owners seek.

Portuguese business owners, but also starting entrepreneurs, score on average higher in all three measured dimensions when compared to other respondents.

Big Five Inventory-44 (BFI-44)

The Big Five Personality Inventory-Version 44 (BFI-44; John et al., 1991) is a 44-item self-administered personality test. The test presents 44 statements, each of which is scored on a 5- point Likert scale as to the subjects’ degree of agreement with how well it describes them. Each dimension is scored as the average of the scores given to each of the statements of that dimension.

The inventory measures the Big Five Factors of personality: Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, and Openness to Experience. The BFI-44 has shown strong internal consistency, retest reliability and clear factor structure, as well as considerable convergent and discriminant validity when compared to the existing longer Big Five measurement instruments.

3.3 Research Questions

In order to carry out this analysis, research questions had to be defined. A research question starts normally with doubt, but it is familiarity with a subject that enables a research team to correctly formulate such questions (Farrugia, Petrisor, Farrokhyar, & Bhandari, 2009). As such, having as departure point the doubts raised by the objectives of the current study and combining that with the experience of the team in studying entrepreneurs’ personality traits, the following research questions were formulated:

1. Do young entrepreneurs have different entrepreneurial psychological traits when compared to their non- entrepreneur peers?

2. Do young entrepreneurs have different personality traits when compared to their non-entrepreneur peers?

3. Do young entrepreneurs show higher scores in what concerns Extroversion and Agreeableness of the BFI-44, and therefore have potentially higher (social) networking skills than their non-entrepreneur peers?

At this point, it is important to emphasise that this study focusses particularly on the capabilities of creating collaborative and commercial networks, i.e. networks of contacts that may help to improve product/service development and/or sales.

3.4 Type of Study

To answer the research questions and to achieve the main objectives of our study a transversal, descriptive, analytical and correlational analysis was performed. Data were treated using IBM® SPSS® Statistics, Version 23, for macOS.

4. Results

The main objective of this research was to identify if there was evidence that entrepreneurial young adults present different traits than their non-entrepreneurial peers and specially in the traits that can give evidence of the lack of networking capabilities. As such, the results will be presented by comparing the respondents that are developing entrepreneurial projects with the ones that are not.

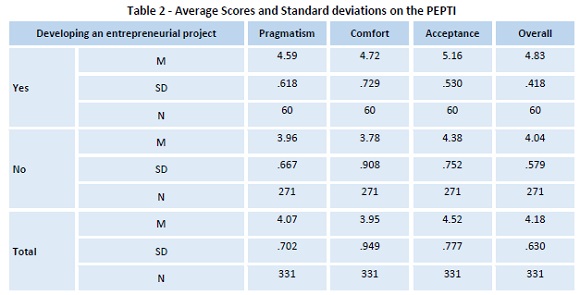

The first step of our analysis was to compare both groups of respondents, based on their scores on the Portuguese Entrepreneurial Psychological Traits Inventory. As can be observed in Table 2, the average score of the people developing an entrepreneurial project is considerably higher for all measured dimensions as well as for the overall score.

The results presented in Table 2, are in line with the results of previous studies using the same measurement instrument (Galvão & Pinheiro, 2016, 2017; Martins et al., 2017), and also in our case show that entrepreneurial individuals have higher levels of pragmatism, a higher need for comfort and also higher needs for acceptance by the community and their peers. These results, answer our first research question partially, as the young entrepreneurs in our sample show higher entrepreneurial psychological traits than their non-entrepreneur peers, although not answering if these higher scores are statistically significant.

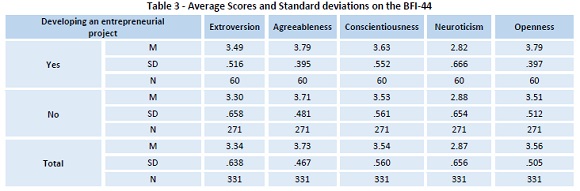

In what concerns the Big Five personality traits, the results presented in Table 3, show that, for the exception of neuroticism, the respondents working on an entrepreneurial project score higher on the remaining four dimensions than their non-entrepreneurial peers.

However, contrary to what is observed in Table 2, the score differences in what concerns the Big Five personality traits, presented in Table 3, are less accentuated. These results answer our second research question partially, as they show higher scores for young entrepreneurs for four of the five dimensions of the Big Five personality traits, when compared to their non-entrepreneur peers, however not proving that these differences are statistically significant. The differences observed in Table 3 are in line with results of previous studies, where entrepreneurs, on average, scored higher on specially Extroversion, Agreeableness and Openness to new experiences (Shipilov et al., 2014; Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000).

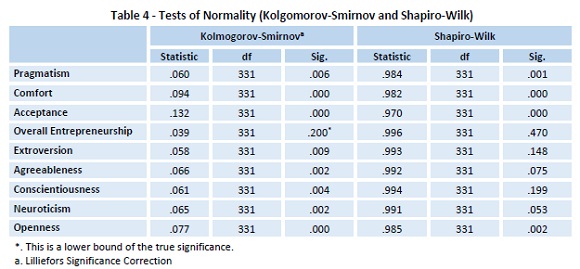

For the next step of our research, we performed the Kolgmorov- Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk normality tests, together with visual observation of the data distribution, to understand if the observed data followed or not a normal distribution. The results of these tests are presented in Table 4, and show substantial differences between both tests, especially in what concerns the data from the Big Five dimensions.

Taking the results presented in Table 4, we would assume, according to the Kolgomorv-Smirnov tests, that the observed data follows non-normal distributed patterns for all dimensions, except for the overall entrepreneurship score. However, notwithstanding the results mentioned above, we opted to attribute more relevance to the results of the Shapiro-Wilk tests, following the recommendations from several existing researchers in this field (Ghasemi & Zahediasl, 2012). As such, to perform the inferential tests, the option fell on parametric tests for the dimensions where the significance level of the Shapiro-Wilk test is above .05 and non- parametric tests for the dimensions where the significance level is below that same threshold.

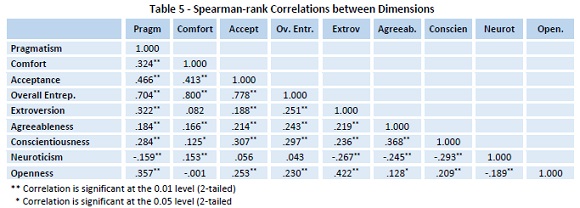

The first inferential analysis we carried out was to identify correlations between the 9 dimensions measured by the two data collection instruments we used. Notwithstanding having a combination of normally and non-normally distributed data, the research team opted for measuring correlations between the dimensions through Spearman-rank order correlations, as this method has been proven to possibly improve power when compared to Pearson correlations when there is a combination of normally and non-normally distributed data (Bishara & Hittner, 2012).

The results of the Spearman-rank correlations are presented in Table 5, showing a statistically significant relationship between most dimensions, although in the majority of cases this correlation is negligible due to its small absolute value (Mukaka, 2012).

The correlation indices presented in Table 5, although showing mostly negligible relationships between the entrepreneurial psychological traits as measured by the PEPTI (Galvão & Pinheiro, 2017) and the Big Five personality traits as measured by BFI-44 (John et al., 1991), are in line with previous findings (Martins et al., 2017).

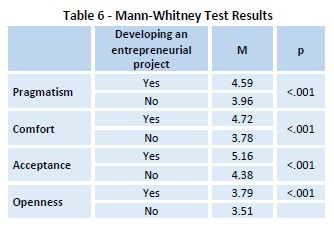

Up to this point, our analysis has shown that young entrepreneurs present higher scores for eight of the nine personality and psychological traits dimensions measured in this study when compared to their non-entrepreneur peers. Our next step was to analyse if these differences between these two groups were statistically significant, and there extrapolatable to the remaining population. To analyse the differences for the four dimensions showing non-normally distributed data, we performed Mann-Whitney tests, being the results of these tests shown in Table 6.

As can be observed from the significance levels presented in Table 6, the test results for all dimensions is <.01, therefore rejecting the null-hypothesis that there are no differences between the groups. With these results, we can state that there are indeed differences in terms of the traits Pragmatism, Comfort, Acceptance and Openness between young entrepreneurs and their non-entrepreneur peers and that young entrepreneurs score, on average, higher on all these four dimensions. These results show stronger differences than in the study that developed the PEPTI (Galvão & Pinheiro, 2017), as even for the dimension Comfort, a statistically significant difference was found, while the original study only found statistically significant differences for all dimensions in the cases that one of the groups was composed out of business owners. However, in the original study, former students that were not working full-time on an entrepreneurial project, i.e. they were employed, were not included in the analysis. Therefore, the results of the current study and the study of Galvão and Pinheiro (2017) are not directly comparable on this level. The statistically significant difference between the two groups in what concerns Openness to new experiences is in line with previous studies where entrepreneurs scored higher than non- entrepreneurs (Davis et al., 2016; Wolff & Kim, 2012).

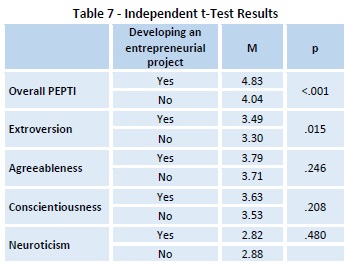

For the five measured dimensions with normally distributed data, independent t-tests were performed, being the results presented in Table 7.

The results of Table 7 show that there is a statistically significant difference between the scores obtained by young entrepreneurs and their non-entrepreneur peers, on the overall PEPTI score and in what concerns Extroversion, scoring the first group higher in both dimensions. However, the statistical significance of the differences was not proven for the remaining dimension, in particular, the dimension Agreeableness, one of the dimensions that, according to previous research, may positively influence networking capabilities (Jensen-Campbell et al., 2003; Nettle, 2006; Shipilov et al., 2014).

The results presented in Table 6 and Table 7, give the final answers to our three research questions, being these answered as follows:

1. Young entrepreneurs have different entrepreneurial psychological traits when compared to their non- entrepreneur peers, and these four traits are stronger in the group of young entrepreneurs.

2. Young entrepreneurs have different personality traits when compared to their non-entrepreneur peers, but only in what concerns Extroversion and Openness to new experiences, these differences, which translate in higher scores, can be considered statistically significant.

3. Young entrepreneurs do show higher scores in what concerns Extroversion and Agreeableness of the BFI-44, but only in what concerns Extroversion, these differences can be considered statistically significant. Therefore, having, or not, potentially higher networking skills than their non- entrepreneur peers, is not proven, as Agreeableness plays an equally important role in networking skills and no statistically significant differences were proven.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

The results of our study confirm, as in several other studies, that there are indeed differences in the psychological and personality traits of entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs (Galvão & Pinheiro, 2016, 2017; Jensen-Campbell et al., 2003; Martins et al., 2017; Shipilov et al., 2014). In the used sample, the subjects developing an entrepreneurial project score on average higher on all entrepreneurial psychological traits from the Portuguese Entrepreneurial Psychologic Traits Inventory as well as on the overall score of this same inventory, and the observed differences are statistically significant. In what concerns the Big Five personality trait there were also differences between the two subgroups, with the entrepreneurial young adults showing higher scores on Extroversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness and Openness to new experiences, and lower scores on Neuroticism. However, only for the dimensions Extroversion and Openness to new experiences, the measured differences have shown statistically significant.

This study builds on these previous findings, adding a new objective, that is, to find psychological and personality traits that may need to be enhanced to improve entrepreneurial performance, such as studied here, the personality traits Extroversion and Agreeableness, to enhance (social) networking capabilities.

Given the results as mentioned earlier, and particularly in what concerns the personality trait Agreeableness, the fact that the differences are not statistically significant, may be an indication of why Portuguese entrepreneurs underperform in terms of networking abilities. As pointed out in other studies, high scores for this trait, are an indication of potentially higher (social) networking capabilities (Shu et al., 2018; Wolff & Kim, 2012) and therefore, the non-existence of statistically significant differences between the entrepreneurs in the sample and the remaining respondents, may indicate that Portuguese entrepreneurs have a less strong trait than would be considered ideal for enhancing networking capabilities.

Our study’s starting point was one of the conclusions of Ács et al. (2017) in the Global Entrepreneurship Index 2018, where it is stated that Portugal’s weakest area in what concerns entrepreneurship is networking. On the other hand, several studies conclude that Extroversion and Agreeableness are two personality traits directly related to networking capabilities (Denissen & Penke, 2008; Forret & Dougherty, 2001; Jensen- Campbell et al., 2003; Lee & Tsang, 2001; Nettle, 2006; Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000).

Given the aforementioned, we can conclude that there may indeed be a need to look deeper at the personality trait Agreeableness and the eventual relationship of lower networking capabilities of Portuguese entrepreneurs and also to propose adequate solutions to enhance those capabilities.

In practical terms, the entrepreneur needs to develop three core competences: strategic thinking - for instance, how to transform and idea into a business or how to present a value proposition to the market that has economical value; vision - the capacity to dream, imagine, but also to have the ambition to implement; and execution - to be able to implement, set goals and apply the correct methodologies to develop their projects (Martins et al., 2017).

Our recommendation, based on existing studies as well as on the current one carried out by our team, is to implement a psychological coaching programme alongside the entrepreneurial programmes, as the latter focus mainly or sometimes even exclusively, on hard-skills and entrepreneurial methodologies, leaving the soft-skills or behavioural or psychological traits aside. These psychological coaching programmes would both serve to evaluate and map the entrepreneur’s traits as well as to help him or her to better understand themselves and, through that, better adapt to what it takes to be an entrepreneur on several levels. Other studies in Portugal have concluded that such programmes would help the entrepreneurs to overcome better the hardships of starting an entrepreneurial project (Galvão, Pinheiro, & Fernandes, 2016; Martins et al., 2017).

Through psychological coaching, the entrepreneurs will better understand their personality traits, their personal and professional maturity, their shortcomings and simultaneously plan and implement development actions that will capacitate them for the several challenges that come with developing a business project. Coaching, as a useful tool in developing and enhancing entrepreneurial traits, has been mentioned in several different studies (Premand et al., 2016), and helps the entrepreneur to identify traits, behaviours or preconceived beliefs that limit their capabilities and simultaneously to analyse and deconstruct these limiters.

From the several definitions of coaching, we opt, in this context, for defining Coaching psychology as “being the systematic application of behavioural science to the enhancement of life experience, work performance and well-being for individuals, groups and organisations who do not have clinically significant mental health issues or abnormal levels of distress” (Grant, 2006, p. 16). In this context, the coach works together with the coachees, the entrepreneurs, and helps them to identify and construe possible solutions that allow them to reach set out goals.

The proposed methodology is the integrative model of psychological coaching, where the coachee, the entrepreneur, is understood as intrinsically creative, resourceful and complete (Whitworth, Kimsey-House, Kimsey-House, & Sandahl, 2007), adapted to face changes and with a global vision. This methodology has strong roots in a humanistic approach to coaching, based on the works of several authors such as Goleman (1995) and Maslow (1954), and has as central principle, that individuals have natural skills to develop themselves aiming at an optimised functioning and that emotions have a real influence on economic activity and leadership.

The objectives of this programme are to promote abilities among the young entrepreneurs in order for them to accomplish their best personal development as well as to achieve their goals in their professional life. This proposal intends to contribute to an education that promotes the development of mindsets, knowledge and competences that are relevant for entrepreneurship and is fully aligned with the best existing practices.

REFERENCES

Ács, Z., Szerb, L., & Lloyd, A. (2017). The Global Entrepreneurship Index 2018. Washington, D.C.: The Global Entrepreneurship and Development Institute.

Beck, T., Demirguc-Kunt, A., Laeven, L., & Levine, R. (2008). Finance, firm size, and growth. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 40(7), 1379-1405. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-4616.2008.00164.x [ Links ]

Biggiero, L. (2001). Self-organizing processes in building entrepreneurial networks: a theoretical and empirical investigation. Human Systems Management, 20(September), 209-222. [ Links ]

Bishara, A. J., & Hittner, J. B. (2012). Testing the significance of a correlation with nonnormal data: Comparison of Pearson, Spearman, transformation, and resampling approaches. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 399-417. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028087 [ Links ]

Carree, M. A., & Thurik, A. R. (2010). The Impact of Entrepreneurship on Economic Growth. Em Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research (pp. 557-594). New York, NY: Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1191-9_20

Davis, M. H., Hall, J. A., & Mayer, P. S. (2016). Developing a new measure of entrepreneurial mindset: Reliability, validity, and implications for practitioners. Consulting Psychology Journal, 68(1), 21-48. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000045 [ Links ]

Denissen, J. J. A., & Penke, L. (2008). Motivational individual reaction norms underlying the Five-Factor model of personality: First steps towards a theory-based conceptual framework. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(5), 1285-1302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2008.04.002 [ Links ]

Farrugia, P., Petrisor, B. A., Farrokhyar, F., & Bhandari, M. (2009). Practical tips for surgical research: Research questions, hypotheses and objectives. Canadian journal of surgery. Journal canadien de chirurgie, 53(4), 278-281. https://doi.org/10.1503/cjs.036311

Forret, M. L., & Dougherty, T. W. (2001). Correlates of Networking Behavior for Managerial and Professional Employees. Group and Organization Management, 26(3), 283-311. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601101263004 [ Links ]

Galvão, A., & Pinheiro, M. (2016). Predisposição para o empreendedorismo : as características psicológicas podem-nos dizer algo sobre os empresários portugueses ? Em 3o Congresso da Ordem dos Psicólogos Portugueses (pp. 923-933). Porto. [ Links ]

Galvão, A., & Pinheiro, M. (2017). Pragmatism, need for comfort and need for acceptance - psychological traits for successful entrepreneurship in Portugal. Journal of Spatial and Organizational Dynamics, V(3), 264-277. [ Links ]

Galvão, A., Pinheiro, M., & Fernandes, P. O. (2016). Idiosyncratic psychological aspects in entrepreneurship. Em Proceedings of the International Congress on Interdisciplinarity in Social and Human Sciences (pp. 171-178). [ Links ]

Ghasemi, A., & Zahediasl, S. (2012). Normality tests for statistical analysis: A guide for non-statisticians. International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 10(2), 486-489. [ Links ]

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam. [ Links ]

Grant, A. M. (2006). Coaching Psychology. International Coaching Psychology Review, 1(1), 12-22. [ Links ]

Jack, S. L. (2010). Approaches to studying networks: Implications and outcomes. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(1), 120-137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.10.010 [ Links ]

Jensen-Campbell, L. A., Gleason, K. A., Adams, R., & Malcolm, K. T. (2003). Interpersonal Conflict, Agreeableness, and Personality Development. Journal of Personality, 71(6), 1059-1085. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.7106007 [ Links ]

John, O., Donahue, E., & Kentle, R. (1991). The Big Five Inventory - Versions 4a and 54. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(6), 504-528. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1 [ Links ]

John, O., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. Handbook of personality: Theory and research, 2(510), 102-138.

https://doi.org/citeulike-article-id:3488537

Lee, D. Y., & Tsang, E. W. K. (2001). The effects of entrepreneurial personality, background and network activities on venture growth. Journal of Management Studies, 38(4), 583-602. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00250 [ Links ]

Marques, A. P. (2016). Aprendizagens Empreendedoras no Ensino Superior: Redes, Competências e Mercado de Trabalho. Vila Nova de Famalicão: Edições Humus, Lda. [ Links ]

Martins, S., Galvão, A., & Pinheiro, M. (2017). Social entrepreneurship, psychological coaching as a developer of competences. Em III Congresso Ibero-Americano de Empreendedorismo, Energia, Ambiente e Tecnologia Social (pp. 413-418). [ Links ]

Maslow, A. H. (1954). A theory of human motivation. Motivation and Personality, (7), 15-31. [ Links ]

Mukaka, M. M. (2012). Statistics corner: A guide to appropriate use of correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Medical Journal, 24(3), 69-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2016.01.020 [ Links ]

Nelson, R. E. (2001). On the shape of verbal networks in organizations. Organization Studies, 22(5), 797-823. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840601225003 [ Links ]

Nettle, D. (2006). Psychological profiles of professional actors. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(2), 375-383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.07.008 [ Links ]

Nohria, N., & Eccles, R. G. (1992). Networks and organizations :structure, form, and action. Harvard Business School Press.

Parkhe, A., Wasserman, S., & Ralston, D. A. (2006). New frontiers in network theory development. The Academy of Management Journal, 31(3), 560-568. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2006.21318917 [ Links ]

Premand, P., Brodmann, S., Almeida, R., Grun, R., & Barouni, M. (2016). Entrepreneurship Education and Entry into Self-Employment Among University Graduates. World Development, 77, 311-327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.08.028 [ Links ]

Rego, A. (2000). Os motivos de sucesso, afiliação e poder: desenvolvimento e validação de um instrumento de medida. Análise Psicológica, 3(XVIII), 335-344. [ Links ]

Shane, S. (2004). Encouraging university entrepreneurship? The effect of the Bayh-Dole Act on university patenting in the United States. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(1), 127-151. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00114-3 [ Links ]

Shinnar, R., Pruett, M., & Toney, B. (2009). Entrepreneurship Education: Attitudes Across Campus. Journal of Education for Business, 84(3), 151- 159. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.84.3.151-159 [ Links ]

Shipilov, A., Labianca, G., Kalnysh, V., & Kalnysh, Y. (2014). Network- building behavioral tendencies, range, and promotion speed. Social Networks, 39(1), 71-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2014.03.006 [ Links ]

Shu, R., Ren, S., & Zheng, Y. (2018). Building networks into discovery: The link between entrepreneur network capability and entrepreneurial opportunity discovery. Journal of Business Research, 85, 197-208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.12.048 [ Links ]

Valkokari, K., & Helander, N. (2007). Knowledge management in different types of strategic SME networks. Management Research News, 30(8), 597-608. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409170710773724 [ Links ]

Wanberg, C. R., & Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D. (2000). Predictors and outcomes of proactivity in the socialization process. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 373-385. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.3.373 [ Links ]

Whitworth, L., Kimsey-House, K., Kimsey-House, H., & Sandahl, P. (2007). Co-active Coaching: New Skills for Coaching People Toward Success in Work and Life, 312. [ Links ]

Wolff, H., & Kim, S. (2012). The relationship between networking behaviors and the Big Five personality dimensions. Career Development International, 17(1), 43-66. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620431211201328 [ Links ]

Wood, M. S. (2009). Does one Size fit all? The multiple organizational forms leading to successful academic entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 33(4), 929-947. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00306.x [ Links ]

Received: 18.06.2018

Revisions required: 12.09.2018

Accepted: 15.12.2018