Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.15 no.2 Faro jun. 2019

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2019.150201

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Online travel agencies: factors influencing tourist purchase decision

Online travel agencies: fatores que influenciam a decisão de compra turística

Ivete Pinto1, Conceição Castro2

1Polytechnic Institute of Porto, Rua D. Sancho I, 981, 4480-876 Vila do Conde, Portugal, ivete.eseig.gmail.com

2CEOS.PP, ISCAP, P.PORTO, Polytechnic Institute of Porto, Porto Accounting and Business School Rua Jaime Lopes Amorim, 4465-004. S. Mamede de Infesta, Portugal, CEPESE, mariacastro@iscap.ipp.pt

ABSTRACT

This study aims to analyse the tourist online purchasing behaviour through Online Travel Agencies (OTAs) (Booking.com and Expedia.com), which factors have more influence on the buying decision-making and if the degree of importance given to some factors changes according to socio-demographic, economic or travel characteristics. Results show that most tourists book their accommodation through OTAs, mainly due to the easiness of browsing and the better prices. The results also suggest that the most important factor when booking accommodation is the price, although the buying process is complex, the online reviews, promotions and photos are also important. Regarding the level of importance online tourists give to price, there are differences between age groups, income and country of residence. The online reviews are important regardless of the characteristics of the tourist, except for age. It was possible, through a cluster analyses, to find three different segments of tourists considering the importance given to price, online reviews, promotions and photos.

Keywords: E-commerce, online shopping, online travel agencies, Booking.com, Expedia.com, tourist consumer’s behaviour.

RESUMO

O presente estudo tem por objetivo analisar o comportamento de compra de alojamento turístico através das agências de viagens online (OTAs) (Booking.com e Expedia.com), identificar o fator que exerce maior influência na decisão de compra, e aferir se o grau de importância dado aos fatores se altera com as características sociodemográficas e económicas ou características das viagens. Conclui-se que a preferência pelas reservas nas OTA resulta da facilidade de navegação e melhores preços. O fator mais importante na compra de alojamento através das OTA é o preço, embora o processo de compra seja complexo, e as online reviews, promoções e imagens sejam também relevantes. O grau de importância atribuído ao preço é diferente conforme a idade, rendimento e país de residência, enquanto as reviews online são importantes independentemente do perfil dos turistas, com exceção da idade. A análise de clusters permitiu agrupar os turistas com características semelhantes em três grupos distintos conforme a importância atribuída ao preço, online reviews, promoções e fotografias.

Palavras-chave: E-commerce, compras online, online travel agencies, Booking.com, Expedia.com, comportamento do consumidor turístico.

1. Introduction

The advents of the digital revolution have significantly changed the way tourist products are presented, distributed and sold, as well as the tourist’s consumer behaviour, changing the way they plan travels (No & Kim, 2015). Tourism and travel industry have been recognised as the largest online transaction facilitator, and hotel bookings represent the second-largest source of revenue based on the volume of sales through online channels, after air travel (Conyette, 2012). Since the development of the Computer Reservation System in the 60s to the Global Distribution Systems in the 80s and the developments of the internet in the 90s, the tourism market has been confronted with the exponential increase in technologies that can be considered as an opportunity but also as a challenge (Buhalis & Law, 2008). Currently, Online Travel Agencies (OTAs) are the online sales channels with the highest booking rates and sales, and their main function is the sale and promotion of accommodation in exchange for commissions on sales, as well as other services related to tourism (flights and car rental, among others). Hotels use these online agencies to obtain more visibility and thus increase their sales (Ling, Guo & Yang, 2014).

The travel industry is more competitive than ever, and OTAs should strive to emerge in this sector by employing strategies that meet consumer preferences, who have a multi-criteria decision making. Moreover, nowadays through the online distribution channels, consumers can easily compare the available products, prices, special offers, discounts, access to independent reviews and photographs of the tourism product and all this weighed in their decision. The issue of the influencing factors of the decision-making process through OTAs has not yet been fully investigated by tourism and hospitality researchers. Most of the existing studies focus on the identification and analysis of online consumer behaviours and their decision-making process, and although some analyse the influence of factors such as online reviews and prices on OTAs, they don’t analyse several factors in a comparative framework. The literature has also highlighted the need for understanding tourist online attitudes and behaviours from a socio-demographic perspective, but these effects are still not fully understood in tourism e-commerce, mainly in OTAs.

Therefore, it is essential to know the main factors in the decision-making process and its relative importance in order to find solutions for price and promotion strategies or to enhance the website’s visual appeal in a way that enables to increases customer loyalty, retention and hence sales.

Portugal’s international recognition as a tourist destination has increased tourism substantially, and the current market is extremely competitive, namely in the area of Porto and North of Portugal, also as a result of the considerable tourism investments that were made in these areas. Despite the growing literature in the field of tourism, there is still a limited involvement of researchers about the factors influencing purchasing decision through OTAs, particularly in Portugal.

In this context, the aim of this paper is to identify the main reasons to book accommodation online in Porto and Northern Portugal, to analyse the behaviour of the online tourist consumer who makes purchases of accommodation through the most important OTAs, and identify which factor influences more the final purchase decision, considering, for this purpose, the price, promotions, online reviews and photos. In addition, the objective is to analyse if the degree of importance given to these factors changes according to the socio-demographic characteristics of the online tourist and, through a cluster analysis, to define homogeneous groups of consumers according to the importance of those factors. Since the tourist market is not homogenous, it is, therefore, essential to segment the market to understand the characteristics of online consumers.

The present research intends to fill a gap in the literature, seeking to analyse more deeply the tourist’s behaviour in the OTAs, improving the understanding of the determinants of online purchasing intention of tourists through OTAs, which can help hoteliers to define a more reliable marketing strategy, particularly in Porto and North of Portugal.

Since customer satisfaction is a crucial piece to leverage sales and keep OTAs at a high level of competitiveness, this paper intends to contribute to the understanding of the influence factors in the online buying decision-process and should be of interest to hoteliers and as well as academic investigators to better understand OTAs consumer behaviour.

The article is organised as follows. Section 2 outlines the literature review; Section 3 defines the research objectives, hypothesis and methodology; followed by Section 4, which exhibits the results and analysis. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the main conclusions, presents the limitations of the current work, and also outline directions for future research.

2. Literature review

2.1 Online distribution channels: OTAs

The evolution of the new technologies and the internet has changed the way tourists make accommodation reservations (Rianthong, Dumrongsiri & Kohda, 2016). These behavioural changes led to the development of online booking channels, including OTAs. Although some studies argue that there are no significant differences between traditional and online commerce, many claim that there is a new stage in the purchasing process: the stage of trust-building (Lee, 2002; Pappas, 2017). There are several studies on this subject, focusing on the use of the internet in the process of planning a trip (Ferrer-Rosell, Coenders & Marine-Roig, 2017). In recent years, large distribution channels have invested in technological developments such as social networks, portal developments and smartphone applications. OTAs, which emerged after 1990, dominate the hospitality industry, play a key role in the online distribution channels, and have developed a successful business in the current market by aggregating multiple products/services and reducing fixed costs, in order to provide more attractive products to travellers (Kim, Kim and Kandampully, 2009). OTAs are essential for hotels since they help them to give visibility, thus increasing the interest of tourists and occupancy rates (Ling, Dong, Guo & Liang, 2015).

There are several advantages for consumers to make reservations through OTAs and it usually includes factors such as convenience (Heung, 2003; Kim & Lee, 2004; Pappas, 2017), financial advantages (such as lower prices) (Hao, Yu, Law & Fong, 2015), speed (Heung, 2003; Buhalis & Law, 2008; Agag & ElMasry, 2016), enjoyment (Heung, 2003; Kim & Lee, 2004; Arruda, 2014) and variety of products/services (Liu & Zhang, 2014).

Although travellers use OTAs to search for information about a particular hotel, they often book the room on the hotel's website or by telephone (Wu, Law & Jiang, 2013), preferring personal contact, being able to negotiate the price to obtain more attractive prices than those published online. In order to induce consumers to book in their portal, OTAs usually offer special discounts or promote travel packages (Toh, DeKay & Raven, 2011). The rates of commissions charged by OTAs to hotels can reach up to 30%, so hotels need to have a high sales volume to offset commissions (O’Connor & Murphy, 2008). The study of O’Connor and Murphy (2008) concluded that only 1% to 5% of consumers buy, so the hotels need to improve their profile and visibility to enhance their performance in OTAs. For these reasons, there is a conflicting relationship between the two entities, but through the "billboard" effect (increased bookings through the hotel website due to its presence in an OTA), marketing or advertising benefits of the OTAs highlight the hotel establishments and thus help them to increase their sales. Anderson and Juma (2011) concluded that hotels present on Expedia had an increase in their sales of 7.5% to 26% in direct purchases on the hotel’s website.

2.2 Tourist consumer behaviour - influencing factors

Tourist consumer behaviour is one of the key factors in the hospitality industry. Understanding the motivations that lead the consumer to choose a destination, accommodation and/or services can improve the service and meet the current needs of the tourist. With this information, marketers can improve their products and services in order to satisfy the wishes of costumers. The buying decision process is the result of a multifaceted process and is influenced by internal and external factors (Swarbrooke & Horner, 2007). Motivations, self-concept and personality, attitudes, expectations, perceptions and opinions, lifestyle, past experience are among the internal factors that influence tourism behaviour. External influences include the culture, values, demographics, reference groups, word of mouth, risk, political instability, among others.

Investigation of the consumer behaviour is an issue very important but difficult to assess, particularly in tourism, where the purchasing decision is complex, since it embraces complex services, and tourists buy mostly experiences, and so has emotional elements.

Consumers who want to purchase hotels products/services are frequently influenced not only by the own product but also by the design of the websites, content, attitudes and satisfaction of other tourists (Ku & Fan, 2009; Liu & Zhang, 2014). Consumers can choose a lodging due to its location, brand, facilities, service quality, price, loyalty program, reviews of other guests, among others. All these factors enter into the mix of the consumer’s choice with different weights depending on the characteristics of the tourist and his motivations.

2.2.1 Price

The tourist market usually involves the choice of a destination and a hotel as well as the consumption of products, often for the first time, so this experience involves certain perceived risk levels and sometimes at a fairly high cost. In these situations, price is often one of the main keys in the buying decisionmaking process, making consumers expect that the price they will pay matches the quality of the service (Cirer Costa, 2013). The price paid for accommodation is more than the access to the room, it also includes access to a variety of facilities, and all the attributes and characteristics are taken into account for the consumer's decision and contribute to the experience. There are also intangible elements as the brand image of the hotel or destination that can dematerialise the importance of the price. Factors such as location, events, and unique characteristics can change the base prices of accommodation units as well as different seasons (Espinet, Saez, Coenders & Fluvià, 2003). Each hotel is responsible for setting its prices. However, they should not neglect the influence that distribution channels may have on those prices. In the online market, the prices are accessible to all, which increases competition, and among the several OTAs it is possible to find the same service with different prices. E-commerce services have the advantage of having reduced transaction costs due to the nature of the business, which can provide the best prices and opportunities. On the internet tourists can find prices more appealing than offline, using sites such as OTAs, websites that allow them to compare prices (trivago.com) or websites where the consumer makes an offer of how much he is willing to pay (priceline.com). For Kim and Lee (2004), the price still exerts a significant influence on the reservation intention of online consumers, arguing that highpriced products can prevent the realisation of the reserve since the risk perception increases.

2.2.2 Promotions

Nowadays besides the transparency of rates, resulting from the ease of comparison, the knowledge of the dynamic pricing environment, consumers make judgements about the fluctuation of prices to determine the best moment to buy (Webb, 2016). In fact, promotions both in products and services are increasingly recurrent in today's society. Promotions are useful at various stages of the product life cycle, from encouragement to experimenting, from introducing brand changes to maintaining brand loyalty. Several authors argue that promotions that provide money-saving are the only ones that motivate a consumer response (Blattberg & Neslin, 2002). Martinez and Montaner (2006) found that consumers with more financial constraints are no more prone to promotions than consumers with a higher economic level. These authors analysed several factors that could influence the consumer's propensity to promotions such as socio-demographic and behavioural characteristics. For Soares, Farhangmehr and Ruvio (2008), consumers with higher exploratory tendencies tend to do more research to find the best option and perceive sales promotions as a stimulus to make the final decision. At OTA’s websites, it is possible to find several types of promotions, from free cancellation to price’s reduction. Besides the emphasis given on the platforms through the possibility of free cancellation or pay later, there are still daily highlights that advertise special offers of the day. Casaló and Romero (2019) suggest that promotions (monetary and non-monetary) are an important influence factor in the decision-making process and induce customers to have, voluntarily, helping behaviours of suggestions and word-of-mouth.

2.2.3 Online reviews

One of the most critical factors in OTAs and hotels is the need to show the quality of the service to the consumer. Online reviews are the new word-of-mouth style, and published comments are a trusted resource, an essential source of information and help the online consumer to make a decision (Filieri & McLeay, 2014; Sparks, So & Bradley, 2016) and usually when a potential client reads a negative review it decreases his booking intention (Gavilan, Avello & Martinez-Navarro, 2018). More than 60% of tourism consumers consult online reviews before making an online purchase (Global Market Research, Panel Quality, Lightspeed GMI). Several studies emphasise the importance of reviews to the contemporary tourist consumer (Mateus, 2015; Tsao, Hsieh, Shih & Lin, 2015). According to Mateus (2015), the consumer considers that the information in the online reviews is correct, accurate and reliable and that the hotels with the most significant number of reviews are more popular, thus increasing their credibility. In a study for resorts in Cancun, Book, Tanford, Montegomary and Love (2018) concluded that the nonunanimous reviews become a predominant source of influence supplanting the importance of price.

2.2.4 Photographs

Currently, tourist destinations are largely promoted through photographic representations, since tourism is a visual and unique experience. The travel photos allow to transfer affective feelings to the tourists, and the study of the extent to which the images published in the websites influence the tourists is of extreme importance (Gao & Bai, 2014). Images influence the purchase decision of the tourist, both at the destination level and the final decision level (Rafael & Almeida, 2017) and photographic content, in general, can be more effective to transmit emotional attributes (Mak, 2017).

2.2.5 Socio-demographic characteristics

It is recognised in the literature that socio-demographic characteristics, like gender, age, income, education, and characteristics of the trip differentiate each online tourist (Del Chiappa, 2013; Silva, Filho & Marques Júnior, 2019), but findings are not consensual.

Several authors found that that gender does not influence the behaviour of buying trips online (Morrison, Andrew & Baum, 2001; Kim & Lee, 2004; Buhalis & Law, 2008) while Lin, Featherman, Brooks and Hajli (2018) consider that gender differences exist in online consumer behaviour and purchase decision making and that gender effects remain poorly understood in the e-commerce. Kim, Lehto and Morrison (2007) also conclude that female are more influenced by detailed messages, more visually and intrinsic motivated, rely more in external sources of information, use all the available information, and give more importance to compare prices.

Del Chiappa (2013) in a survey conducted in Italy found that there are significant differences between online costumers based on age, education, income and prior experience with online travel shopping and they can be influenced by usergenerated content in their buying decision. Jensen & Hjalager (2013) suggested that the young, well-educated and highincome travellers compared to lower-income earners tend to be the first movers in taking advantage of the internet in travel planning. Kim and Lee (2004), Garín-Muñoz and Pérez-Amaral (2011) and Morrison et al. (2001) argue that there is no link between income and the probability of buying travels online, although Law and Bai (2008) state that the probability of online reservations increases as income increases.

In relation to the age of the online tourists, Garín-Muñoz and Pérez-Amaral (2011) and Kim and Lee (2004) concluded that tourists over 30 are more likely to make online reservations, as well as Garín-Muñoz and Pérez-Amaral (2011) in which the age group of 35-44 is the one that makes more reservations of accommodation online. According to Weber and Roehl (1999) and Heung (2003), tourists with a higher level of education are those who use more the OTAs. Heung (2003) also concluded that the use of the internet for online purchase of travel products differ across countries. For Silva et al. (2019) the preference given to book accommodations in OTAs differs in the type of travel that the consumer will carry out, and this preference is higher when is a domestic and leisure travel.

3. Objectives, hypotheses and methodology

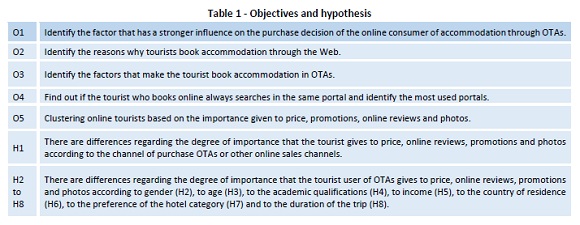

Table 1 identifies the objectives (O) and hypothesis (H) of research in this study.

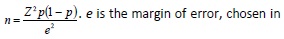

In methodological terms, a quantitative study was chosen through a questionnaire elaborated according to the collected literature on the subject: Anderson and Juma (2011) and Pan, Zhang and Law ( 2013) for the functions of OTAs; Liu, Arnett and Litecky (2000), Blake, Valdiserri, Neuendorf and Valdiserri (2007) and Chen, Mocker, Preston and Teubner (2010) for its size; Cox, Burgess, Sellitto and Buultjens (2009), Chen et al. (2010), Hills and Cairncross (2011), Serra Cantallops and Salvi (2014) and Mateus (2015) for the importance of online reviews; Kracht and Wang (2010) and Pan et al. (2013) for promotions; Hanks (1992), Lee (2002) and Cirer Costa (2013), for the price; and Hanks (1992) and Cirer Costa (2013), for the photos). To fulfil the objectives of this study, it was prepared a questionnaire to gather the necessary information, with 26 questions, built in four languages (Portuguese, English, French and Spanish) in order to reach tourists of different nationalities, and was divided into five sections. The first section aimed to understand if the tourists make their reservation online and, if so, in which portals and the reasons for their choice. The second section inquires about the trip pattern, and the third section aim to reach the factor that more influences the buying decision-making process of accommodation through OTAs and understand the pre-selection procedure. The fourth section was designed to analyse several aspects related to the influence factors - price, promotions, reviews online and photos - and the perceived impact in the buying decision. Finally, a section with demographic questions to understand the profile of respondents. All the survey questions were closed-ended, including dichotomous questions, multiple-choice questions, rank order questions and Likert-type scales in a five-point scale of agreement (from 1-Strongly disagree to 5Strongly agree) and of importance (from 1 - Not important to 5 - Very important).

Since there is no information about the number of tourists booking accommodation in Porto and Northern Portugal through OTAs, it was applied the Cochran’s sample size formula, which is especially appropriate in situations with large populations:

5%, p is the estimated proportion of the population that use OTAs (it was adopted a conservative response format of 50%/50%, according to Akis, Peristianis & Warner, 1996), and Z is the Z-value on the Z table (1.96) and so we got a random sample of 384.

The questionnaire was conducted through the Limesurvey platform and distributed with the help of Mailchimp to a list of more than 6,000 personal and professional e-mails of people from different nationalities. It was further publicised through links on Linkedin, Facebook and national and international travel blogs.

In total, 507 completed questionnaires were collected during the four months of application. Due to the nature of the study, only 397 of these questionnaires were considered valid, since 88 of the respondents did not make their reservations online and 22 did not visit or intend to visit Porto and Northern Portugal. For the analysis, it was used the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) data processing tool, version 23.

To analyse the response bias, the responses from the early and late respondents to the Likert scale questions were compared using non-parametric tests, and there were not found significant differences in the majority of the items (Lindner, Murphy & Briers, 2001). The internal consistency of the results of the questionnaire was evaluated by the Cronbach's coefficient Alpha that proved to be good (0.802) (Pestana & Gageiro, 2008).

Subsequently, a descriptive and inferential statistical analysis of the results was performed. The descriptive analysis allows to study the observed characteristics, as well as to analyse the importance of the purchasing decision factors. To analyse the validity of the hypothesis of the research, it was chosen an inferential analysis, in order to search for differences in the purchasing pattern relative to price, online reviews, promotions and photos and the different characteristics in the analysis. For this purpose, parametric tests were applied in cases where the dependent variable had a normal distribution as assessed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and when the variances of the independent sample groups were homogeneous, as measured by the Levene test (Marôco, 2007). If these conditions are not validated, non-parametric tests are applied. The level of significance considered throughout the analysis was 5%.

To identify different groups of tourists that visited or intended to visit Porto and the North of Portugal according to the importance given to price, promotions, reviews online and photos in the buying making decision of accommodation through OTAs, it was made a cluster analysis, an exploratory technique of multivariate analysis and the profile of the online consumers in each cluster was defined according to the socio-demographic and travel characteristics.

4. Results and analysis

4.1 Sample Characteristics

Of the 397 respondents, 66% are female, and 34% male. 45.1% of the respondents were 34 years or less, the age group more representative is 18-24 years (22.9%), followed by the age group of 25-34 years (22.20%). Only 5.0% of the respondents have more than 65 years. Portugal is the country of residence of the majority of the respondents (57.4%), followed by Spain (20.2%), France (18.4%), Brazil and France (1.3% each). These figures are supported by the study carried out by INE (2015) concerning the main countries of origin from the tourists who come to Portugal. Regarding academic qualifications, tourists in the sample showed high levels of education: bachelors (49.1%), masters (22.7%) and PhD (10.1%). Most respondents have a good economic level, above the national average of €909.50, according to INE (2015). About 35.8% of the subjects have monthly net income between 1001€-2400€, 12.1% between 2401€-3000€, although 28.20% of respondents have incomes less than €750 monthly and 13.9% between 750€-1000€.

In terms of the length of their travel, 51.1% of respondents visited Porto and North of Portugal for 3-7 days, followed by shorter stays of two or fewer days (46.6%) and only 2.3% spent 8 or more nights. Their preferences in terms of hotel categories, although 32.2% and 31.2% of the respondents choose hotels of 4 and 3 stars, respectively, for around 27.5% the category of the hotel is indifferent.

4.2 Tourist behaviour

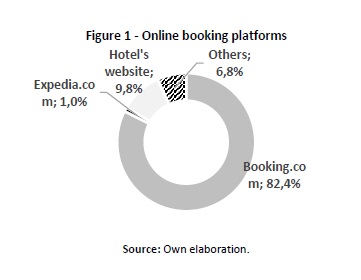

Online tourist consumers book their accommodation primarily on Booking.com (82.4%) and OTAs play a key role in the option of buying tourist accommodation (83.4%) (Figure 1). The hotel’s website receives 9.8% of the accommodation reservations directly, and about 7% of respondents choose other portals: Airbnb, Edreams and Odisseia, among others.

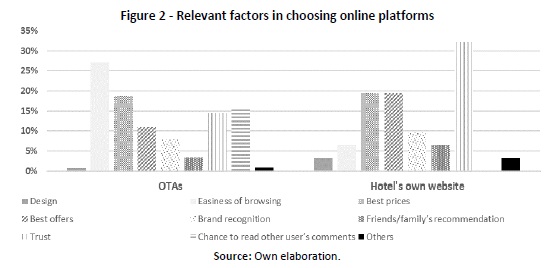

Regarding the reasons for tourists to choose OTAs (Figure 2), the easiness of browsing (27.1%) and better prices (18.7%) are highlighted, while tourists who choose to book their accommodation directly on the website of the hotel mention reliability as the main factor (32.3%), followed by better prices and promotions. These differences in the choice of portals show that the main reason that leads tourists to choose the institutional site of the hotel is the reliability in the brand of a particular hotel chain. Krishnan and Hartline (2001) mention that the level of brand confidence is more significant, depending on the perceived risk. As previously mentioned in the literature review, the online tourism market is considered a market with high perceived risk due to its specific characteristics. Therefore the brand has increased importance.

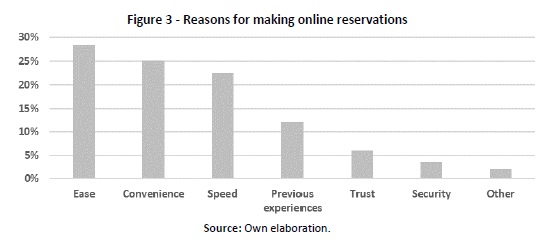

Respondents indicated that they prefer to book online because they consider it easier (28.4%), convenient (25.1%) and faster (22.6%) than traditional booking channels (Figure 3). These results are in line with Heung (2003), who concludes that convenience and time saving are the most important factors when choosing online travel purchases.

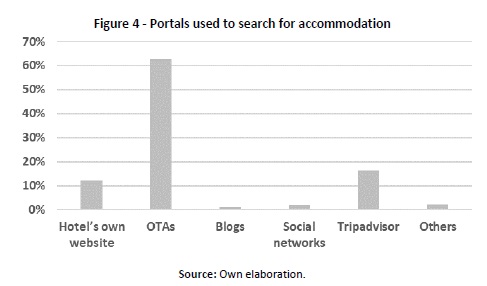

About 96.4% of the respondents stated that they usually research online for accommodation, and the OTAs are the most used portals in this survey (63.0%), followed by the Tripadvisor.com (Figure 4). This fact shows that OTAs are increasingly being used as a search engine, as well as a reservation channel. It was also found that social networks have little impact at the research level, as well as travel blogs.

4.3. Factors influencing the decision of the online tourist consumer

As the main objective of this article is studying OTAs and the most important factor in the purchase decision of the online tourist through these agencies, from the sample of 397 respondents previously analysed there were withdrawn the results of the respondents who chose to buy on other purchase channels: 39 respondents selected the hotel website and 27 other channels. Thus, to continue the study, the number of observations for the second phase of the data analysis is reduced to 331.

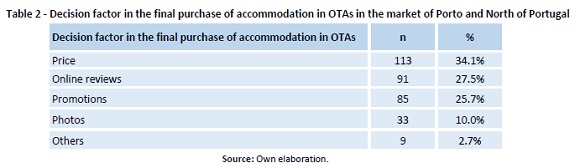

Consumers were asked to choose the most important factor in the buying decision-making of accommodation among price, online reviews, promotions, photos and others. According to the results reported in Table 2, the factor with the most significant influence on the purchase decision of the online travel consumer was the price, followed by online reviews and promotions. Thus, price is the factor considered decisive by 34.10% of the respondents, although there is a very similar distribution between online reviews and promotions.

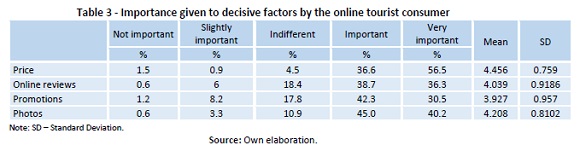

Given the complexity of the decision-making process of the online tourist consumer, it was also asked the importance that each of the factors has in the consumer’s final decision. Table 3 shows that the price is very important in the decision-making process for 56.5% of the respondents and that photos, promotions and online reviews are considered important (45.0%, 42.3% and 38.7%, respectively). These results demonstrate the complexity of the process and that although there is a decisive factor, in this case, the price, all the factors are important in the final decision of the consumer.

The importance given to the price presents a very high average (4.456), higher than photos and online reviews with averages of 4.208 and 4.039, respectively. The lowest average of the four factors is for promotions (3.927). It can be concluded, therefore, that the variables under study are considered of great importance for the respondents.

After analysing the decisive factor in the reservation of accommodation online through OTAs, it was analysed the impact that each of these factors has on the consumer. It was also analysed the degree of reliability that consumers give to the factors presented in the OTAs, and their importance in the decision-making process.

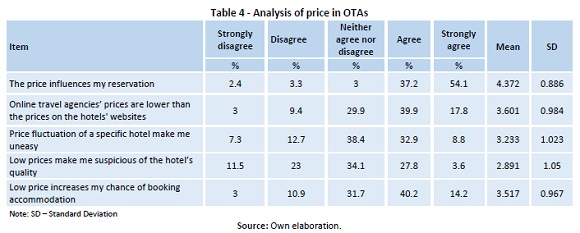

4.3.1 Price

Table 4 shows that the price has great importance in the tourist purchase decision since 54.1% of the respondents strongly agree, and 37.2% agree that it influences their decision. It is also possible to conclude that consumers do not associate that OTAs have lower prices or that there is a direct association between price and quality. The low price increases the possibility of booking accommodation to 54.40% of respondents. According to Morrison et al. (2001) and Kim and Lee (2004) consumers tend to shop online for the lowest prices, although Ku and Fan (2009) argue that the price is not the decisive factor in the purchase of the online tourist, but characteristics as privacy, portal security and product quality, and Book et al. (2018) that price is no longer the leader influence factor.

4.3.2 Promotions

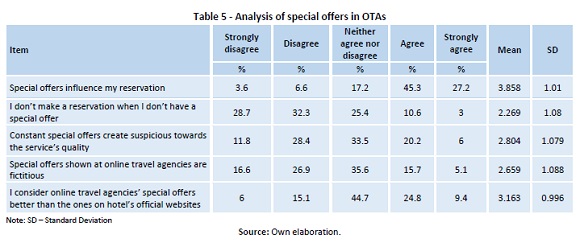

Table 5 shows that the inexistence of special offers does not necessarily cause the tourist to give up the reservation and that the consumer does not consider that consecutive promotions cause distrust in the quality of the service. Respondents are not suspicious of the promotions advertised in OTAs, considering them truthful, reliable and more appealing than the ones on the institutional websites of the hotels. Although 72.5% of the respondents agree or strongly agree that promotions influence their reservation of accommodation, 61.0% make their reservation even without a promotion. The analysis of promotion and price suggest that the consumer does not associate economic factors with the quality of services of the hotels and that the OTAs’ users trust in the published financial information.

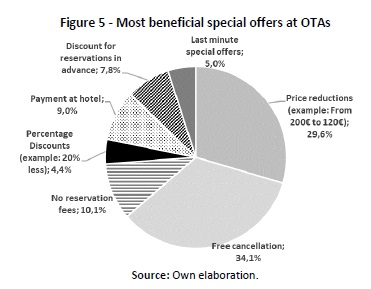

We also asked about the type of promotions that consumers consider to be more relevant in their purchasing process in OTAs (Figure 5). About 34% of the respondents indicated the possibility of free cancellation and 29.0% price reductions. These options could be explained by the current social and economic instability of the markets. There is currently a high unpredictability in these two characteristics, justified by financial, economic and political aspects, besides terrorism and even natural disasters, which makes the consumer give importance to the possibility of free cancellation.

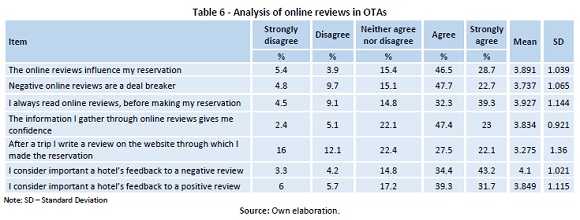

4.3.3 Online reviews

Online reviews are very important for the online tourist consumer. Nowadays, there is a high demand for online reviews, as well as an increase in the contribution of tourists through the publication of their comments in the post-purchase process. According to the results, online reviews are important in the consumer’s decision-making process, although it is not the most important factor. However, negative reviews have a high impact on the purchase decision (Table 6). It is also possible to conclude that most of the consumers consult online reviews and that they consider their relevance in the process, although they do not contribute with their comments. The feedback from the hotel to a client’s comment is considered as very relevant in the reservation process since the consumer can assess the social responsibility of the hotel and its ability to solve after-sales situations.

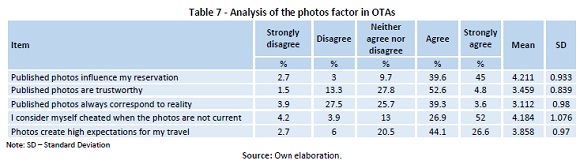

4.3.4 Photos

Photos advertised by OTAs are considered as very important in the final purchase decision. Table 7 indicates that the consumer does not consider that photos are always in accordance with the current reality of the accommodation, which leads to the loss of reliability. The results also revealed that photos are directly linked to the creation of expectations and that when they do not correspond to the true image of the accommodation, it creates a sense of distrust.

4.4 Analysis of research hypothesis

In order to obtain answers to the hypothesis of research of this study, several parametric tests were used, and when the assumptions of the application of the same were violated, nonparametric tests were produced, based on the data analysis techniques mentioned previously.

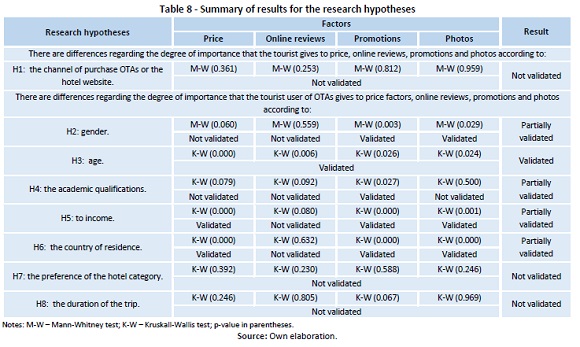

The results of the tests (Table 8) suggest that there are no statistically significant differences in the importance given to price, online reviews, promotions and photos depending on the portal used (OTAs or other online sales channels) (H1). It was also concluded (H2) that the observed differences between the importance given by male and female online tourist to promotions and photos are statistically significant and women give more importance to promotions and photos than men, but they give the same importance to price and online reviews. Also Morrison et al. (2001), Kim and Lee (2004) and Buhalis and Law (2008) conclude that gender does not influence the behaviour of buying trips online.

Regarding the third hypothesis, the results suggest that there are differences statistically significant in the importance that online travel consumers give to all the factors according to the age segments. The pairwise comparisons evidence significant differences in price relevance for the age groups 18-34 and 4554 years with those with 55 and more years, and it is the younger travellers (18-34 years) and the age group 45 to 55 years who are more concerned with the price. Differences in the importance given to promotions are observed between the youngest (18-24 years) and oldest (65 and more) and, in average, the youngest followed by the age group between 4554 years give more relevance to that factor. The online reviews are, on average more important to online tourist between 25 and 34 years, and this group is statistically different from travellers with more than 45 years. The photos are more valued by young consumers (18-24 years) and significantly different from the age group 55 to 64 years. Garín-Muñoz and Pérez-Amaral (2011) and Kim and Lee (2004) also found differences between age groups in the online reservations of accommodation.

Regarding academic qualifications, there are differences in the importance that consumers of OTAs give to promotions, and these differences are observable between travellers with secondary school and PhD degree, but not concerning price, online reviews and photos (H4). The level of income influences the importance that consumers of OTAs give to price, promotions and photos, but not to online reviews. As expected, the differences statistically significant are between consumers with low and high incomes. Online tourists with incomes between 3001€ and 4000€ are those who, on average, give less importance to price and photos while consumers with levels of income higher than 4000€ are less sensitive to promotions. Law and Bai (2008) argue that the probability of online reservations increases as income increases, while Kim and Lee (2004), GarínMuñoz and Pérez-Amaral (2011) and Morrison et al. (2001) found no relationship. The country of residence of the online consumer is not determinant in the importance given to the online review, but there are differences between Spanish and French online tourists with Portuguese travellers in terms of the other factors (H6). Brazilian tourists put a higher value on price. Heung (2003) also found differences in online consumer behaviour by home country.

Finally, the results suggest that hotel category (number of stars) and average travel length do not influence the importance the consumers give to the four factors under analysis (H7 and H8).

4.5. Cluster Analysis

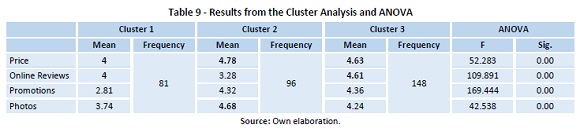

To identify homogeneous groups of travellers according to the importance given to price, online reviews, promotions and photos in the buying decision-making in OTAs, it was made a cluster analysis. It was applied Ward’s hierarchical procedure with square Euclidean distance as a measure of dissimilarity between the respondents. The Z-scores were calculated for each one of the variables. To eliminate the outliers Z-scores identified as being lower than -3.6 and higher than 3.6, 6 cases were eliminated, which reduced the sample to 325 observations. Subsequently, the analysis was refined from the K-means technique and the three-cluster resolution provided the most interpretable result. Table 9 displays, for the three clusters identified, the mean scores for prices, online reviews, promotions and photos. The analysis of the F-value of a oneway ANOVA allows concluding that all clustering variables’ means differ significantly (Sig.<0.05), however, the variables that allow greater discrimination among the clusters are the promotions followed by the online reviews.

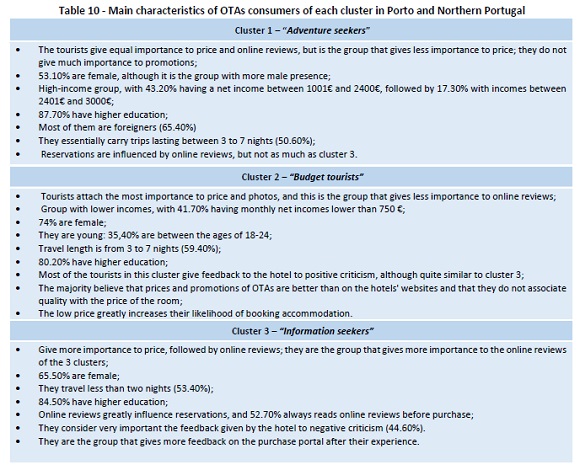

In cluster 1 - labelled Adventure seekers - the most important factors in the purchase decision through the OTAs in Porto and North of Portugal are the price and online reviews with equal weights; in cluster 2 - Budget tourists - is the price followed by the photos and in cluster 3 - Information seekers - the most important factors are the price and the online reviews. In this last clusters, online reviews have de highest mean and comprise almost half of the tourists surveyed (45.54%). In this analysis, it is confirmed that the price is the most important factor in the purchase decision of the tourists of the OTAs in the market of Porto and North of Portugal.

In table 10, the main characteristics of the different clusters are synthesised.

5. Conclusions

It is undeniable the impact that OTAs have had on global travel and hospitality. Digital revolution has shifted the pattern of how travellers make the booking, and OTAs are nowadays an important distribution channel, where consumers can do searches related to travel and reservations.

This study demonstrates the importance of OTAs as a distribution channel since most travellers use this kind of agencies to book accommodation. In terms of the importance of OTAs attributes, easiness of browsing and better prices were the most highlighted factors. Travellers who book directly on the hotel’s website emphasise trust, followed by better prices.

Based on the results, for online tourists that book in OTAs the most critical factor in the buying decision-making was the price, but promotions, online reviews and photos have also an important impact on the final decision and several consumers’ socio-demographic characteristics affect the importance given to these factors. The clusters’ analysis allowed to group the tourists in three groups with different online purchase behaviours depending on their characteristics and shopping options, and in each one the price appears as the most important factor in the buying decision-making of lodging of the consumer online through OTAs, validating the previous results. The cluster formed by the "Adventure Seekers" is the group that is below the average in all the factors under analysis. Most of them are foreign and give little importance to promotions. The group formed by the "Budget tourists" are more aware of the economic factors and give less importance to online reviews. From the three clusters, this is the group formed by tourists with lower incomes, and that states that low prices increase their probability of reservation. Among all the clusters, "Information seekers" is the one that gives more relevance and publishes more online reviews and makes trips with less overnight stays.

This research highlights the importance of the hospitality industry to be present in OTAs, in order to increase visibility and sales.

The findings have several practical importance. The better one knows the consumer’s buying decision and the market segments, the more it can help hoteliers, especially the marketing department, to define commercial strategies, namely of positioning in OTAs. Based on the results, and although price is the most important factor in the decisionmaking process when booking accommodation in Porto and North of Portugal through OTAs, these online distributors should improve the image of the services they sell, by the use of advanced technologies, such as virtual reality, 3D technology, product video, panorama image or live streaming to display the products. Online reviews are important sources of information and there is a need to continue to invest in platforms that help monitor online reviews, manage online reputation and use guest feedback to improve service quality.

Knowing the consumer’s patterns of behaviour and the profile of consumers in each segment, marketers can determine which market segments are relevant for their product or service or even for strategic decisions in the future and so the findings can help online travel companies’ managers to develop appropriate strategies that drive loyalty and enhance intentions to purchase accommodation online through OTAs.

Despite the research contribution, some limitations also provide grounds for further research. First, the dimension of the sample once the response rate was low and so generalisations of the results must be made with caution. The analysis did not allow us to study the differences in the consumer’s behaviour in different OTAs concerning the influence factors in the analysis since there was insufficient data for a substantial and reliable analysis. Further research should be done to compare the results suggested in the present study with results obtained from users of other OTAs. Also, future research is needed to replicate and progress the findings of this study. To overcome the current limitations, developments should be made using more representative samples, not only in dimension but also including users of other OTAs, along with other target regions. In addition, this is an exploratory study and different research methodologies, such as confirmatory factor analysis or estimation using structural equation modelling analysis should be conducted.

Given the constant evolution of the OTA channels, there are other themes and characteristics of the platforms that can be studied. Although some consumer characteristics were analysed, it would be important to make a comparison of the various influencing factors with the motivation of the travel and the different lifestyles of consumers. Finally, it would be interesting to carry out a more extensive analysis of how the various factors presented in the portals: facilities, location, specific characteristics (pet-friendly, gay-friendly, among others) affect tourist behaviour.

REFERENCES

Agag, G., & El-Masry, A. (2016). Understanding consumer intention to participate in online travel community and effects on consumer intention to purchase travel online and WOM: An integration of innovation diffusion theory and TAM with trust. Computers in Human Behavior, 60, 97-11. [ Links ]

Akis, A., Peristianis, N., & Warner, J. (1996). Residents’ attitudes to tourism development: The case of Cyprus. Tourism Management, 17(7), 481-494. [ Links ]

Anderson, W., & Juma, S. (2011). Linkages at tourism destinations: Challenges in Zanzibar. ARA Journal of Tourism Research, 3(1), 27-41. [ Links ]

Arruda, F. (2014). A importância da promoção turística nas redes sociais. Thesis. ESHTE - Escola Superior de Hotelaria e Turismo do Estoril. [ Links ]

Blake, B., Valdiserri, C., Neuendorf, K., & Valdiserri, J. (2007). The online shopping profile in the cross-national context: The roles of innovativeness and perceived innovation newness. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 19(3), 23-51. [ Links ]

Blattberg, R., & Neslin, S. (2002). Sales promotion: concepts, methods, and strategies. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Book, L., Tanford, S., Montegomary, R., & Love, C. (2018). Online traveler reviews as social influence: Price is no longer king. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 42(3), 445-475. [ Links ]

Buhalis, D., & Law, R. (2008). Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet - The state of eTourism research. Tourism Management, 29(4), 609-623. [ Links ]

Casaló, L., & Romero, J. (2019). Social media promotions and travelers’ value-creating behaviors: the role of perceived support. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(2), 633-650. [ Links ]

Chen, D., Mocker, M., Preston, D., & Teubner, A. (2010). Information systems strategy: Reconceptualization, measurement, and implications. MIS Quarterly, 34(2), 233-259. [ Links ]

Cirer Costa, J. (2013). Price formation and market segmentation in seaside accommodations. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 33, 446-455. [ Links ]

Conyette, M. (2012). A framework explaining how consumers plan and book travel online. International Journal of Management and Marketing Research, 5(3), 57-67. [ Links ]

Cox, C., Burgess, S., Sellitto, C., & Buultjens, J. (2009). The role of usergenerated content in tourists’ travel planning behavior. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 18(8), 743-764. [ Links ]

Del Chiappa, G. (2013). Internet versus travel agencies - The perception of different groups of Italian online buyers. Journal Of Vacation Marketing, 19(1), 55-66. [ Links ]

Espinet, J., Saez, M., Coenders, G., & Fluvià, M. (2003). Effect on prices of the attributes of holiday hotels: a hedonic prices approach. Tourism Economics, 9(2), 165-177. [ Links ]

Ferrer-Rosell, B., Coenders, G., & Marine-Roig, E. (2017). Is planning through the Internet (un)related to trip satisfaction?. Information Technology & Tourism, 17(2), 229-244. [ Links ]

Filieri, R., & McLeay, F. (2014). E-WOM and accommodation: An analysis of the factors that influence travelers’ adoption of information from online reviews. Journal of Travel Research, 53(1), 44-57. [ Links ]

Gao, L., & Bai, X. (2014). Online consumer behaviour and its relationship to website atmospheric induced flow: Insights into online travel agencies in China. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 21(4), 653-665. [ Links ]

Garín-Muñoz, T., & Pérez-Amaral, T. (2011). Internet usage for travel and tourism: the case of Spain. Tourism Economics, 17(5), 1071-1085. [ Links ]

Gavilan, D., Avello, M., & Martinez-Navarro, G. (2018). The influence of online ratings and reviews on hotel booking consideration. Tourism Management, 66, 53-61. [ Links ]

Global Market Research, Panel Quality Lightspeed GMI. Retrieved 15 October 2018 from http://www.lightspeedresearch.com/ [ Links ]

Hanks, R. (1992). Discounting in the hotel industry: A new approach. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 33(1), 15-23. [ Links ]

Hao, J., Yu, Y., Law, R., & Fong, D. (2015). A genetic algorithm-based learning approach to understand customer satisfaction with OTA websites. Tourism Management, 48, 231-241. [ Links ]

Heung, V. (2003). Internet usage by international travellers: reasons and barriers. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 15(7), 370-378. [ Links ]

Hills, J., & Cairncross, G. (2011). Small accommodation providers and UGC web sites: perceptions and practices. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 23(1), 26-43. [ Links ]

INE-Instituto Nacional de Estatística [INE] (2015). Retrieved 15 October 2018 from https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpgid=ine_main&xpid=INE&xlang= pt/ [ Links ]

Jensen, J., & Hjalager, A-M. (2013). The role of demographics and travel motivation in travellers’ use of the internet before, during, and after a trip. International Journal of Tourism Policy, 5(1/2), 34-58. [ Links ]

Kim, D-Y., Lehto, X., & Morrison, A. (2007). Gender differences in online travel information search: Implications for marketing communications on the internet. Tourism Management, 28, 423-43. [ Links ]

Kim, J., Kim, M., & Kandampully, J. (2009). Buying environment characteristics in the context of e-service. European Journal of Marketing, 43(9/10), 1188-1204. [ Links ]

Kim, W., & Lee, H. (2004). Comparison of web service quality between online travel agencies and online travel suppliers. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 17(2-3), 105-116. [ Links ]

Kracht, J., & Wang, Y. (2010). Examining the tourism distribution channel: evolution and transformation. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 22(5), 736-757. [ Links ]

Krishnan, B., & Hartline, M. (2001). Brand equity: is it more important in services?. Journal of Services Marketing, 15(5), 328-342. [ Links ]

Ku, E., & Fan, Y. (2009). Knowledge sharing and customer relationship management in the travel service alliances. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 20(12), 1407-1421. [ Links ]

Law, R., & Bai, B. (2008). How do the preferences of online buyers and browsers differ on the design and content of travel websites?. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 20(4), 388-400. [ Links ]

Lee, P.-M. (2002). Behavioral model of online purchasers in ecommerce environment. Electronic Commerce Research, 2(1-2), 75-85. [ Links ]

Lin, X., Featherman, M., Brooks, S., & Hajli, N. (2018). Exploring gender differences in online consumer purchase decision making: An online product presentation perspective. Information Systems Frontiers, 1-15.

Lindner, J., Murphy, T., & Briers, G. (2001). Handling nonresponse in social science research. Journal of Agricultural Education, 42(4), 43-53. [ Links ]

Ling, L., Dong, Y., Guo, X., & Liang, L. (2015). Availability management of hotel rooms under cooperation with online travel agencies. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 50, 145-152. [ Links ]

Ling, L., Guo, X., & Yang, C. (2014). Opening the online marketplace: An examination of hotel pricing and travel agency online distribution of rooms. Tourism Management, 45, 234-243. [ Links ]

Liu, C., Arnett, K., & Litecky, C. (2000). Design quality of websites for electronic commerce: Fortune 1000 webmasters’ evaluations. Electronic Markets, 10(2), 120-129. [ Links ]

Liu, J., & Zhang, E. (2014). An investigation of factors affecting customer selection of online hotel booking channels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 39, 71-83. [ Links ]

Mak, A. (2017). Online destination image: Comparing national tourism organisation's and tourists' perspectives. Tourism Management, 60, 280-297. [ Links ]

Marôco, J. (2007). Análise Estatística com Utilização do SPSS. 3a edição. Lisboa: Edições Sílabo. [ Links ]

Martínez, E., & Montaner, T. (2006). The effect of consumer’s psychographic variables upon deal-proneness. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 13(3), 157-168. [ Links ]

Mateus, F. (2015). Online Reviews and Reserva de Hotéis: Análise dos factores que influenciam a adopção de informação disponibilizada pelas online reviews no site booking. com. Thesis. Universidade Europeia. [ Links ]

Morrison, A., Andrew, R., & Baum, T. (2001). The lifestyle economics of small tourism businesses. Journal of Travel and Tourism Research, 1(12), 16-25. [ Links ]

No, E., & Kim, J. (2015). Comparing the attributes of online tourism information sources. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 564-575. [ Links ]

O’Connor, P., & Murphy, J. (2008). Hotel yield management practices across multiple electronic distribution channels. Information Technology & Tourism, 10(2), 161-172. [ Links ]

Pan, B., Zhang, L. and Law, R. (2013). The complex matter of online hotel choice. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 54(1), 74-83. [ Links ]

Pappas, N. (2017). Effect of marketing activities, benefits, risks, confusion due to over-choice, price, quality and consumer trust on online tourism purchasing. Journal of Marketing Communications, 23 (2), 195-218. [ Links ]

Pestana, M., & Gageiro, J. (2008). Análise de dados para ciências sociais a complementaridade do SPSS. Lisboa: Sílabo. [ Links ]

Rafael, C., & Almeida, A. (2017). Socio-demographic tourist profile and destination image in online environment. Journal of Advanced Management Science, 5(5), 373-379. [ Links ]

Rianthong, N., Dumrongsiri, A., & Kohda, Y. (2016). Improving the multidimensional sequencing of hotel rooms on an online travel agency web site. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 17, 74-86. [ Links ]

Serra Cantallops, A., & Salvi, F. (2014). New consumer behavior: A review of research on eWOM and hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 36, 41-51. [ Links ]

Silva, G., Filho, L., & Marques Júnior, S. (2019). Analysis of the perception of accommodation consumers on the use of online travel agencies (OTAs). Brazilian Journal of Tourism Research, 13 (1), 40-57. [ Links ]

Soares, A., Farhangmehr, M., & Ruvio, A. (2008). Exploratory behavior: a Portuguese and British study. Advances in Consumer Research, 35, 675-677. [ Links ]

Sparks, B., So, K., & Bradley, G. L. (2016). Responding to negative online reviews: The effects of hotel responses on customer inferences of trust and concern. Tourism Management, 53, 74-85. [ Links ]

Swarbrooke J., & Horner S. (2007). Consumer Behavior in Tourism. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Toh, R., DeKay, C., & Raven, P. (2011). Travel planning: Searching for and booking hotels on the internet. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 52(4), 388-398. [ Links ]

Tsao, W.-C., Hsieh, M.-T., Shih, L.-W., & Lin, T. (2015). Compliance with eWOM: The influence of hotel reviews on booking intention from the perspective of consumer conformity. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 46, 99-111. [ Links ]

Webb, T. (2016). From travel agents to OTAs: How the evolution of consumer booking behavior has affected revenue management. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management, 15(3-4), 276-282. [ Links ]

Weber, K., & Roehl, W. (1999). Profiling people searching for and purchasing travel products on the world wide web. Journal of Travel Research, 37(3), 291-298. [ Links ]

Wu, E., Law, R., & Jiang, B. (2013). Predicting browsers and purchasers of hotel websites: A weight-of-evidence grouping approach. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 54(1), 38-48. [ Links ]

Received: 22.06.2018

Revisions required: 13.09.2018

Accepted: 15.12.2018