Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.15 no.2 Faro jun. 2019

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2019.150202

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Analysis of the influence of cultural distance on the intention to visit Spain as a tourist destination

Análisis de la influencia de la distancia cultural en la intención de visitar el destino turístico España

German Gemar1, Ismael P. Soler2, Henar Villar3

1University of Malaga, Department of Economics and Business Administration, Spain, ggemar@uma.es

2University of Malaga, Department of Applied Economics, Spain, ipsoler@uma.es

3University of Malaga, Department of Applied Economics, Spain, henar_villar@hotmail.com

ABSTRACT

In the tourist sector, visiting tourists’ intention has been the subject of numerous investigations for decades. However, the determining factors of the choice of tourist destination have not been clearly defined. The culture of the country of origin has been recognised as a key element in discerning the varied behaviours that people display. In this study, the capacity of the cultural distance between the considered countries of origin and Spain, according to the model proposed by Hofstede, is evaluated to influence the intention of visiting Spain in the next years, measured as a function of the theory of planned behaviour. The results obtained allow identification of the relevant issues affecting potential tourists’ intention of visiting. Analysis of the validity and reliability of the data used yields satisfactory solutions that enable the establishment of conclusions about behavioural intentions that are very different depending on the cultural distance level of the tourist. The ability of the Hofstede model to explain the intention to visit Spain is, therefore confirmed.

Keywords: Hofstede model, cultural distance, intention to visit, theory of planned behaviour.

RESUMEN

En el sector turístico, la intención de visita ha sido objeto de numerosas investigaciones desde hace décadas, sin embargo los factores determinantes de la elección del destino turístico no han quedado claramente definidos. La cultura del país de origen se ha reconocido como elemento clave a la hora de discernir las conductas tan variadas por las que optan las personas. En este estudio, se evalúa la capacidad de la distancia cultural entre los países de origen considerados y España, según el modelo propuesto por Hofstede, de influir en la intención de visitar nuestro país en los próximos años, medida ésta en función la Teoría del Comportamiento Planificado - y otros dos factores añadidos. La interpretación de los resultados permite identificar las cuestiones relevantes en la intención de visita de los potenciales turistas. Los análisis de validez y fiabilidad de los datos empleados arrojan soluciones satisfactorias que permiten así establecer conclusiones sobre intención conductual muy distintas en función de los niveles de distancia cultural del turista. Se confirma, por tanto, la capacidad del modelo de Hofstede de explicar la intención de visita de España.

Palabras clave: Modelo de Hofstede, distancia cultural, intención de visita, Teoría del Comportamiento Planificado.

1. Introduction

Culture has been the subject of extensive debate and analysis. Linton (1945) defines the culture of a collective as the configuration of learned behaviour and its results whose elements have been transmitted by the members of a particular society, whereas for Hofstede it is a collective mental programming that allows differentiating the members of one group or category from those of another (Hofstede, 1984, 2011). What does exist is a consensus on the significant influence that culture exerts on human behaviour (Soares, Farhangmehr, & Shoham, 2007), modifying the way of seeing the world (Ueltschy & Krampf, 2001), such as how we consume (Mollá, Berenguer, Gómez, & Quintanilla, 2006), and influencing our actions in an unconscious, subtle and automatic way (Schiffman & Kanuk, 2010). Karahanna, Evaristo and Srite (2006) suggest the existence of different cultural levels, ranging from the supranational level (religion, culture of consumption, etc.), to the group level (family, groups of friends, etc.), although the most studied cultural level is usually the national. Culture is a dynamic concept (Briley, Wyer, & Li, 2014) that must be seen as an adaptive process that facilitates the election criteria for individuals (Rivas & Esteban, 2004) and helps expedite the resolution of problems (Schiffman & Kanuk, 2010). For all these reasons, the cultural conception of Pla and León (2008) has been taken as a reference for this study: they identify culture as a set of norms and values implicit in a collective that gives meaning to their behaviours and endow them with identity. The difference between cultures in a given aspect can constitute a cultural dimension (Hofstede, 2011), giving rise to the concept of cultural distance, which seeks to compare the different cultures among themselves.

Cultural differences between countries have been studied from different perspectives; also, there are various measures and indices from different authors that can be used to measure cultural distance. As of today, there is no agreement on which of the measurements is the most appropriate. Among the most widespread are the seven-dimensional scale of Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner (2011) and the scale of Gesteland (1999), who establishes four dimensions to identify cultural differences and that has been used within tourism research-for example, by Gémar (2014)-for the strategic analysis of the internationalisation of hotels. Another of the most popular scales is that of Hofstede, which has evolved from the original four-dimensional model of 1984 to the last version that identifies six dimensions: power distance (PD), uncertainty avoidance (UA), individualism (IDV), masculinity (MAS), longterm orientation (LTO) and indulgence (IND). The first four belong to the original Hofstede (1984) model, while the fifth (LTO) was added following research by Hofstede and Bond (1988) and the sixth dimension incorporated after the work by Hofstede, Hofstede and Minkov (2010).

Despite the significant influence that culture can exert on the behaviour of tourists, research in this regard is scarce and imprecise, and its evidence is limited (Ng, Lee, & Soutar, 2007). Most researchers choose economic indicators as estimators of tourism demand (e.g. Lee, Morrison, & O’Leary, 2006; Morley, 1998), though other authors like Turner, Reisinger, and Witt (1998) have shown that social variables can play an essential role in tourists’ choice of tourist destination and others such as Ng et al. (2007) place culture as one of the most significant variables in tourists' choice of tourist destination for their vacations. Therefore, this study aims to assess the ability of cultural distance between the countries of origin considered and Spain to influence the intention to visit the country in the coming years, according to the model proposed by Hofstede (2011).

This paper is structured as follows. After this introduction, the conceptual framework on which the present work is based will be revealed, and then, in section three, the methodology used will be explained. In section four, the main results of the research will be collected, which will be discussed in section five. Finally, the main conclusions of this work, its possible limitations and future lines of research will be presented in section six.

2. Conceptual Framework

The tourist’s intention to visit is formed thanks to a rational decision and choice process. It is presumed that certain intentions accurately predict concrete behaviours. Multiple researches have shown a positive relationship between human attitudes and the future behaviour of buyers. Applied to the tourism sector, the behaviour of the current tourist can be explained by his intention to select a city as a tourist destination (Kim & Jun, 2016). Different approaches have sought to clarify what factors influence the tourist's intention to visit a tourist destination. According to Bianchi, Milberg and Cúneo (2017), a large part of these analyses employ Ajzen’s (1985) theory of planned behaviour (TPB). TPB defends that human behaviour is guided by three types of consideration: behavioural, which is confidence in the likely results of a behaviour and its evaluation; normative, which is the expectations of others and the motivation to fulfil them; and control, which is belief about the presence of factors that will facilitate or impede the development of a behaviour, and the perceived power of those factors. The basic premise of this theory is that the intention to carry out a certain behaviour by a subject will be increased if (1) that behaviour allows him to obtain a valuable result; (2) the people around him approve said behaviour; and (3) he has the capacity and resources to develop it (Lam & Hsu, 2004).

The first one (1) generates a favourable or unfavourable attitude towards a behaviour-i.e. a positive or negative inclination towards a particular behaviour such as visiting a tourist destination. Normative impulses (2), in turn, result in perceived social pressure or subjective norms-i.e. social pressure perceived by an individual to develop behaviour or not, and the inclination to adjust to that social pressure. The last consideration (3) will result in a certain perceived level of behaviour control-i.e. society's perception of the ability to perform a particular behaviour, such as visit a tourist destination. In short, the attitude towards behaviour, the subjective norms and the perception of control will guide individuals towards the formation of a behavioural intention. The general rule is that the more favourable the attitude towards a behaviour, the more favourable the subjective norms and the better the perceived level of control, the greater the intention of the person to act in a certain way.

When scholars research intention to visit, it is common for them to use the TPB but add other variables to their analysis, thus forming extended models that respond to other aspects that would otherwise be excluded (e.g. Bianchi et al., 2017; Hamilton & White, 2008). Thus, we find familiarity with the tourist destination as one of these added factors. Numerous empirical researches show that a high level of familiarity with a destination positively affects their image and intention to visit (e.g. Prentice, 2004; Yang, Yuan & Hu, 2009). Travellers feel safe in familiar environments, while new environments are perceived as places of greater risk (Chen & Lin, 2012). Familiarity with the destination reduces the perception of risk and provides more confidence in the choice of destination (Lepp & Gibson, 2003). Familiarity with a tourist destination can increase with previous personal tourist experience or with information about the destination (Baloglu, 2001). Likewise, the ideal social self-concept completes studies based on TPB. Being consists of a set of identities that reflect tasks that the individual must fulfil in a social context (Stryker, 1968, 1986). This set is organised hierarchically according to which are the most valued and important tasks socially, and the subject will act accordingly. That is to say when someone identifies with another person who acts in a certain way, this behaviour becomes an important part of their own perception, influencing their motivation for a specific behaviour (Hamilton & White, 2008).

An important addition to the TPB is the proposal by Gollwitzer (1999), which distinguishes between intention as a state of will (guidance towards a behavioural goal) and implementation intention. This author points out that the correlation between behaviours and intentions is limited, and can only explain 20-30 per cent of our behaviours. He tries to determine the characteristics that turn an intention into action, identifying factors that contribute to forming an intention: the degree of commitment to the intention, specific and precise objectives, achievable and close purposes, among others. Once our intention has been defined, we need an implementation intention-that is to say, one in which, whenever situation A appears, response B begins, aimed at achieving the specific objective, while the simple intention only indicates the attempt to reach the objective. The implementation intention specifies when, where and how to perform the behaviours, indicating a commitment to respond in a certain way to a specific situation (Conner & Armitage, 1998).

Therefore, to analyse the intention to visit Spain as a tourist destination, the TPB has been chosen due to its ability to predict the intention of visiting a tourist destination having been demonstrated in previous investigations (e.g. Maestro, Gallego & Requejo, 2007; Sparks & Pan, 2009). However, in this analysis, we will also study if the three factors that compose it exert a significant influence on the real intention being evaluatedthat is, the intention to visit Spain in the next one or two years.

Regarding the cultural distance scale, this work employs Hofstede's (2011) most recent scale, which includes the six dimensions described below.

• Power distance (PD): This is the degree to which individuals with less power in organisations accept an unequal distribution of power.

• Uncertainty avoidance (UA): This is the degree to which individuals react with suspicion, or feel insecure, in new or ambiguous situations. The greater the aversion to risk, the more necessary will be the rules defined to mark the behaviour.

• Individualism vs. collectivism (IDV): This is the level of concern for caring for oneself and one's immediate environment (individualism) or for larger groups to which the individual feels closely linked (collectivism).

• Masculinity vs. femininity (MAS): This measures society's preference for values traditionally associated with the masculine profile, such as success or competitiveness, compared to values associated with the feminine, such as quality of life, cooperation and relationships with others.

• Long-term vs. short-term orientation (LTO): This evaluates the time horizon of society. While a society with long-term orientation presents a focus on future rewards and values such as perseverance and saving, short-term societies seek to resolve immediate concerns.

• Indulgence vs. containment (IND): This values the degree to which members of a culture try to control their desires and impulses. Indulgence is the will to make real the impulses to enjoy life and have fun; containment is high control of impulse satisfaction with strict social norms.

3. Methodology

3.1 Data

To carry out the research, a survey was conducted. The data collection was carried out for approximately three months, from the end of December 2016 until 29 March 2017, and was limited to citizens of five European countries: Italy, Belgium, France, the United Kingdom and Ireland. This allowed the majority of participants to respond in their own language. Italian respondents who had difficulties with the language were offered the possibility of requesting additional information or clarifications if necessary. At the closure of the data collection period, a total of 190 valid responses to the questionnaire had been obtained.

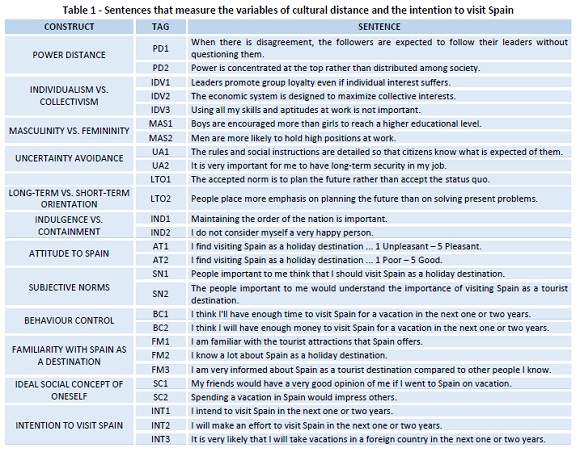

The questionnaire was divided into four parts. A first introductory part offered a brief explanation of the purpose of the questionnaire. A second part collected socio-demographic data such as nationality, sex, age (at intervals from eighteen years), marital status and educational level. The following section included the intention to visit Spain and consisted of fourteen statements related to the probability of choosing Spain as the next tourist destination with which the respondent was asked to declare their level of agreement or disagreement according to a five-point Likert scale from (1) “strongly disagree” to (5) “totally agree”. In addition, this section included a question about whether the respondent had previously visited Spain and another open-ended short answer question that would indicate any thoughts that come to mind when thinking of Spain as a tourist destination. The last section included the measurement of the cultural distance between the country of origin and Spain through thirteen affirmations, again using a five-point Likert scale. Table 1 shows the statements that shaped the intention to visit Spain and cultural distance.

3.2 Model and hypothesis

SPSS software has been used to carry out the corresponding analysis and obtain the results. The demographic profile of the sample, the factorial analysis and the cluster analysis were obtained using it. With the intention of determining the existing relational structure between the variables and to verify the validity of the pre-established constructs, a factorial analysis was carried out, which results in a reduced set of dimensions that explain the variability of the scores of the total group of variables (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001). Finally, the cluster analysis allowed the respondents to be grouped impartially according to their answers to the questionnaire, trying to achieve maximum homogeneity within the same group and the greatest difference between groups (Kaufman & Rousseeuw, 2009).

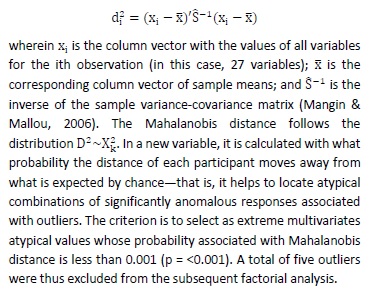

Before the factorial analysis, we proceeded to the analysis for the detection of atypical cases. For this, the Mahalanobis distance (D2) procedure was used. This statistical measure indicates the multidimensional distance of an individual concerning the centroid or average of the observations. Its expression is the following:

In this analysis, the degree of correlation between variables was evaluated, this matrix reflecting a large number of correlations between variables with significant values. In addition, the Kaiser-Mayer-Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s sphericity test were performed. While the high level for the KMO demonstrates the good capacity of the data to adapt to the model, the value of Bartlett’s sphericity test discards the hypothesis of initially uncorrelated variables (Soler & Gemar, A measure of tourist experience quality: the case of inland tourism in Malaga, 2017); both values are suitable for applying the method of principal components analysis for extracting factors. This method allows us to reduce the variables to a smaller set of uncorrelated variables that retain most of the variance of the original variables (Sabio, Kostin, GuillénGosálbez, & Jiménez, 2012). To determine the cut point, the Kaiser criterion was used-that is, to select for the extraction of those components whose eigenvalues are greater than 1 (López-Toro, Diaz-Munoz, & Perez-Moreno, 2010).

Next, we obtain the matrix of components-the unchanged factor matrix-that expresses the correlations between the original variables and each one of the factors. Since this matrix is difficult to interpret, it has undergone a rotation procedure common in this type of analysis (e.g. Soler & Gemar, 2017; Soler, Gemar & JimenezMadrid, 2017). The rotation allows the factorial solution to approach a simple structure. Its purpose is to eliminate the important negative correlations and thus reduce the number of correlations of each item in the various factors.

Finally, in order to categorise the group of individuals into groups, a cluster analysis is carried out. As usual, a cluster analysis is carried out in two stages. In line with Soler et al. (2017), a first stage is carried out with a hierarchical cluster analysis that aims to choose the optimal cut-off point and, with that, the number of clusters to be chosen; then an analysis of Kmeans clusters is performed, setting a priori the optimum number of clusters obtained previously.

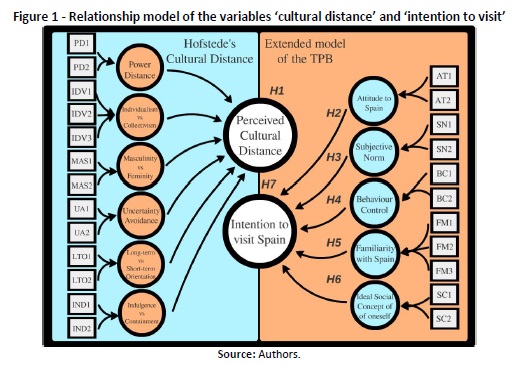

Figure 1 presents a synthesis of the factors, variables and hypotheses that are analysed in this investigation. The final objective will be to measure the influence exerted by the cultural distance between each of the countries analysed and Spain on the intention to visit the country as a tourist destination in the next one or two years.

First, it must be verified if the answers obtained in this study coincide with the values of cultural distance between the countries analysed and Spain indicated by Hofstede. Thus, the first hypothesis is:

H1. The perception of cultural distance by the respondents between their countries of origin and Spain is coincident with the values of cultural distance obtained by Hofstede.

Based on previous work on the influence of TPB on the intention to visit the destination, the following hypotheses are included:

H2. The attitude towards Spain as a tourist destination exerts a significant and positive influence on the intention to visit Spain in the next one or two years.

H3. The subjective norms exert a significant and positive influence on the intention to visit Spain in the next one or two years.

H4. The level of control of perceived behaviour exerts a significant and positive influence on the intention to visit Spain in the next one or two years.

In addition, with the aim of complementing the theory, especially in the case of absence of the expected positive relationship between the three factors that make up the TPB and the intention to visit Spain, it is considered appropriate to incorporate two more factors into this section.

H5. Familiarity with Spain as a tourist destination is a determining factor in the intention to visit Spain in the next one or two years.

H6. The ideal social concept of oneself is a determining factor in the intention to visit Spain in the next one or two years.

Finally, fulfilling the main objective of the study is the seventh and last hypothesis:

H7. The perceived cultural distance between the countries analysed and Spain influences the intention to visit the tourist destination Spain in the next one or two years.

This hypothesis has been decomposed, in turn, into the following sub-hypotheses based on the different countries of origin analysed:

H7.1. The perceived cultural distance between Italy and Spain influences the intention of Italian respondents to visit the tourist destination Spain in the next one or two years.

H7.2. The perceived cultural distance between Belgium and Spain influences the intention of Belgian respondents to visit the tourist destination Spain in the next one or two years.

H7.3. The perceived cultural distance between the United Kingdom and Spain influences the intention of British respondents to visit the tourist destination Spain in the next one or two years.

H7.4. The perceived cultural distance between France and Spain influences the intention of French respondents to visit the tourist destination Spain in the next one or two years.

H7.5. The perceived cultural distance between Ireland and Spain influences the intention of Irish respondents to visit the tourist destination Spain in the next one or two years.

4. Results

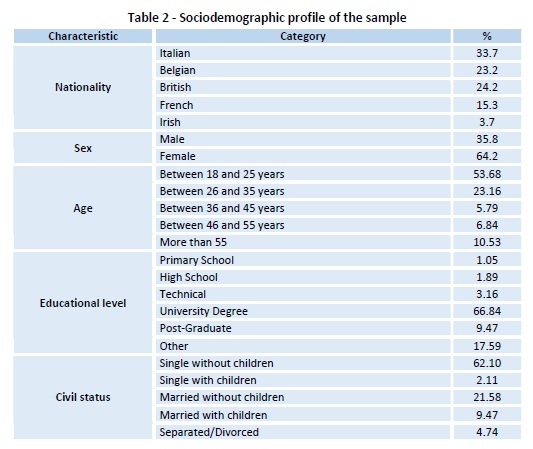

Table 2 shows the socio-demographic profile of the sample. In terms of the nationality of respondents, 33.70 per cent are Italian, 23.20 per cent Belgian, 24.20 per cent British, 15.30 per cent French and 3.7 per cent Irish. With regard to the majority gender, there is a greater percentage of females. According to age, it is observed that 53.68 per cent of the respondents belong to the age group 18-25 years. Finally, the majority civil status (62.11 per cent of respondents) is single without children.

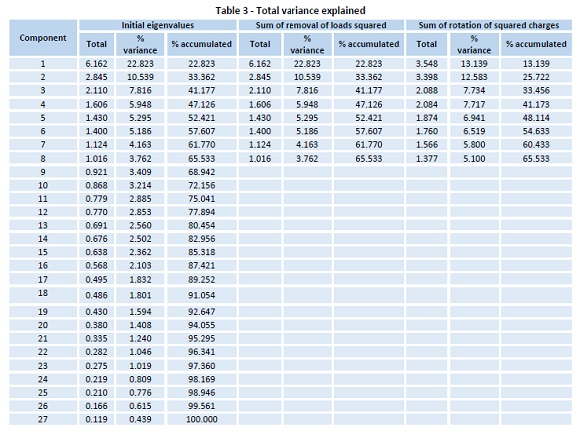

Next, Table 3 shows the total variance explained by each of the components.

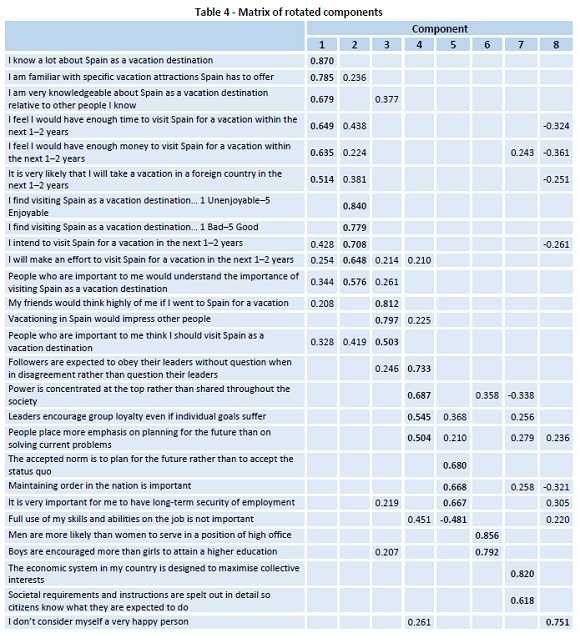

Table 4 shows the final solution rotated from the factorial analysis.

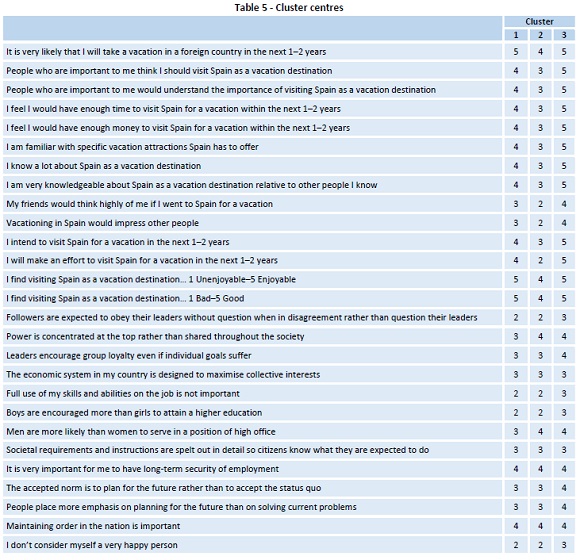

Regarding the cluster analysis, the number of conglomerates was determined as three after the first stage, later developing the analysis of K-means clusters. Table 5 shows the centres of the final clusters.

5. Discussion

Regarding the interpretation and naming of the resulting factors, it is possible to identify that of the rotated components described in Table 4, 1 to 3 effectively group the variables of intention to visit, while components 4 to 8 relate variables of cultural distance. The denomination given to the obtained groupings is as follows.

• Loyalty to the destination Spain. This first factor accounts for 22.82 per cent of the variance and groups six indicators related to control of perceived behaviour, familiarity with Spain as a destination, and intention to travel abroad in the next one or two years. This factor is defined as the client's loyalty from the attitudinal approach, which has been recognised in the literature as a specific attitude to maintain an exchange relationship as a result of past experiences (Sanchis & Saura, 2006).

• Stimulus conditioned to the expectations of the tourist destination Spain. This component is formed by the variables related to attitude towards Spain as a tourist destination, intention to travel to Spain in the next one or two years, and one of the variables of the subjective rules section, and explains 10.54 per cent of the variance. The intention to travel to Spain is conditioned to the expectations that a subject has of Spain as a tourist destination-i.e. it is a cause and effect relationship in

which the expectation precedes the intention of going to Spain (Belloch, Sandín, & Ramos, 2012; Pérez Acosta, 2010).

• Social recognition derived from the visit to Spain. This factor explains 7.82 per cent of the variance and groups variables ‘ideal social concept of oneself’ and an indicator of subjective norms. This grouping of variables resembles the esteem (recognition) needs described by Maslow (1975) in his hierarchy of human needs.

• Leadership. The fourth factor includes four variables related to distance to power, individualism/collectivism, and shortor long-term orientation. It represents 5.95 per cent of the variance and groups items related to leadership as an attitude to influence the way others act, as well as socially ideal behaviour.

• Vital certainty. This factor refers to the knowledge and certainty that the individual has of his own life, from his work situation to his perception of security, and that allows him to make decisions easily based on the forecast of the state of certain variables in the future. This factor expresses 5.30 per cent of the variance and groups four variables that are each related to a different cultural distance factor in the Hofstede (2011) classification.

• Femininity-Masculinity. This component is the only one that remains identical to that previously established by Hofstede (2011). It explains 5.19 per cent of the variance of the model and is related to the distinction of emotional roles between men and women. Masculinity indicates that the roles of each gender are truly different, expecting that men are aggressive, tough and focused on material success, while women are modest, sensitive and oriented towards quality of life. Femininity indicates that the roles of each gender are equal, overlapping each other (Sanchis & Saura, 2006).

• Social promotion. This symbolises the empowerment of collective development through the establishment of social guidelines that allow the maximisation of social welfare. It explains 4.16 per cent of the variance.

• Unhappiness. Finally, although with a single identifying element (I don’t consider myself a very happy person), the last factor described as adverse luck or misfortune. This represents 3.76 per cent of the variance.

Regarding the cluster analysis, given that the questions were posed on a five-point Likert scale, scores greater than 2.5 indicate a positive inclination towards the question, while lower values reflect disagreement with the statement. Thus, cluster 1 is formed by individuals who will most likely travel to a foreign country in the next one or two years, think that Spain is a pleasant and profitable destination, are familiar with the destination of Spain, and value above all long-term security in employment and the safeguarding of national security. Cluster 2 identifies those who think with less certainty that they will travel abroad in the next one or two years, consider Spain as a good vacation destination, believe that power is concentrated at the top, that society defends masculinity, and that long-term security in employment and national security are essential. Finally, cluster 3 brings together the most loyal tourists to Spain who will travel abroad in the next one or two years and will try to do so in Spain, and who think that the distance to power in their nation is high, that it defends masculinity and that who prefer the long term planning. Finally, regarding the belonging of each of the cases to each conglomerate, the first cluster is the most numerous, grouping 109 observations; the second groups 24 and the last 37. When analysing the members of each cluster by nationality, it is observed that at least 50 per cent of the respondents from all the countries belong to cluster 1. In the composition of the second and third clusters, the behaviour is not the same: the British, Irish and Italians predominantly belong to cluster 3, while Belgian and French respondents are most representative in cluster 2.

The results of the factorial analysis demonstrate the usefulness of the TPB as a conceptual framework to predict the intention of potential visitors to Spain. Hypotheses 2 to 6 are also verified, even though the application of this theory in the context of travel intention has not been generally defended in previous surveys (Lam & Hsu, 2004). However, from factorial regrouping, three determining variables of the intention to visit are obtained: loyalty to the destination, stimulus conditioned on expectations, and social recognition. In future studies, it would be interesting to delve into this new regrouping of TPB variables in order to establish a theory of specific behavioural intention for the tourism sector that until the date, is non-existent.

With regard to cultural distance, the results confirm Hofstede’s (2011) values for each of the dimensions that explain it according to nationality. The applicability to the study of the cultural distance variables established by Hofstede has been verified, as well as their importance as a determinant of tourists’ behavioural intentions. Although the discussion in the literature has focused on the masculinity-femininity dimension (Sanchis & Saura, 2006), the biggest controversies in this research are around the individualism-collectivism and indulgence-containment variables due to their limited contribution to the study and the difficulty of separating them from the rest of the cultural dimensions.

6. Conclusion

This research contributes, from an intercultural perspective to the investigation of the intention to visit Spain in the next one or two years. Regarding the results obtained, it must be borne in mind that the analysis of both visiting intention and cultural distance has been carried out separate dimensions to verify the reliability of the results of the joint study. To measure the cultural distance, the Hofstede model has been shown to be ideal. The intention to visit a tourist destination in the coming years has been measured according to the variables of the TPB with the addition of two new factors, supported by literature, offering a theoretical contribution to the model to be taken into account in future investigations. Likewise, the standards of cultural identity of certain countries have been analysed to assess the cultural distance from Spain. Given the few studies on the influence of cultural distance on the behaviour of tourists, the present study tries to fill that gap.

This research reaffirms the validity of tourism studies in relation to the culture of the country of origin. Given the rapidity with which international exchanges evolve, all research work in this area is insufficient, so it should be continued and extended to other areas such as marketing or advertising. It is necessary in future work to develop causal models that also allow prediction of the values of the dependent variable so that the partial least squares (PLS) model would be an option. As a future research line, it is also possible to consider the incorporation of new countries. In the case of Italy, given that its spurious level of cultural distance with Greece and Spain, the visiting intention of Greek nationals could be studied to compare if the results persist in countries with similar cultures. In addition, a discriminant analysis could be interesting in future research. While in a cluster analysis the groups are unknown a priori, as was the case in the present work, in a discriminant analysis the groups are known, and what it has to be learned is to what degree the available variables actually discriminate those groups.

The main limitations lie in the methodology. Since factor analysis is conceived as a general diagnostic method to obtain information in a rational way, it does not necessarily reveal all the forces that affect a specific reality. Therefore, it needs the judgement of the researcher to correct or improve the tool.

Regarding the cluster analysis, this depends on the quality of the variables used, so it requires correct prior analysis of the data. Perhaps the most important limitation of the research is the nationalities chosen for the study, because of their similarity in cultural terms; however, these cultural approaches have allowed the drawing of useful conclusions not only in the field of cultural distance, but also in relation to the dimension linked to the intention to visit. Other obvious limitations are, for example, the small number of responses of Irish nationals compared to the rest of the countries of origin, and the high percentage of female respondents.

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action control (pp. 11-39). Berlin: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. [ Links ]

Baloglu, S. (2001). Image variations of Turkey by familiarity index: Informational and experiential dimensions. Tourism Management, 22(2), 127-133. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00049-2 [ Links ]

Belloch, A., Sandín, B., & Ramos, F. (2012). Manual de psicopatología. Madrid: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Bianchi, C., Milberg, S., & Cúneo, A. (2017). Understanding travelers' intentions to visit a short versus long-haul emerging vacation destination: The case of Chile. Tourism Management, 59, 312-324. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2016.08.013 [ Links ]

Briley, D., Wyer, R. S., & Li, E. (2014). A dynamic view of cultural influence: A review. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 24(4), 557-571. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2014.02.003 [ Links ]

Chen, C. C. & Lin, Y. H. (2012). Segmenting mainland Chinese tourists to Taiwan by destination familiarity: A factor-cluster approach. International Journal of Tourism Research, 14(4), 339-352. doi: 10.1002/jtr.864 [ Links ]

Conner, M. & Armitage, C. J. (1998). Extending the theory of planned behavior: A review and avenues for further research. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28(15), 1429-1464. doi: 10.1111/j.15591816.1998.tb01685.x [ Links ]

Gémar, G. (2014). Influence of cultural distance on the internationalisation of Spanish hotel companies. Tourism & Management Studies, 10(1), 31-36. [ Links ]

Gesteland, R. R. (1999). Cross-cultural business behavior: Marketing, negotiating, sourcing and managing across cultures. Copenhagen: Copenhagen: Business School Press. [ Links ]

Gollwitzer, P. M. (1999). Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. American Psychologist, 54(7), 493-503. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.54.7.493 [ Links ]

Hamilton, K. & White, K. M. (2008). Extending the theory of planned behavior: The role of self and social influences in predicting adolescent regular moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 30(1), 56-74. doi: 10.1123/jsep.30.1.56 [ Links ]

Hofstede, G. (1984). Culture consequences. International Differences in Work-Related Values. Newbury Park: Sage. [ Links ]

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Reading in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 1-26. doi: 10.9707/2307-0919.1014 [ Links ]

Hofstede, G. & Bond, M. H. (1988). The Confucius connection: From cultural roots to economic growth. Organizational Dynamics, 16(4), 521. doi: 10.1016/0090-2616(88)90009-5 [ Links ]

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Karahanna, E., Evaristo, J. R., & Srite, M. (2006). Levels of culture and individual behavior: An integrative perspective. Advanced Topics in Global Information Management, 5(1), 30-50. [ Links ]

Kaufman, L. & Rousseeuw, P. J. (2009). Finding groups in data: An introduction to cluster analysis. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Kim, S. & Jun, J. (2016). The impact of event advertising on attitudes and visit intentions. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 29, 18. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2016.04.002 [ Links ]

Lam, T. & Hsu, C. H. (2004). Theory of planned behavior: Potential travelers from China. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 28(4), 463-482. doi: 10.1177/1096348004267515 [ Links ]

Lee, G., Morrison, A. M., & O’Leary, J. T. (2006). The economic value portfolio matrix: A target market selection tool for destination marketing organizations. Tourism Management,, 27(4), 576-588. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2005.02.002 [ Links ]

Lepp, A. & Gibson, H. (2003). Tourist roles, perceived risk and international tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(3), 606-624. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(03)00024-0 [ Links ]

Linton, R. (1945). The cultural background of personality. England: Appleton-Century. [ Links ]

López-Toro, A. A., Diaz-Munoz, R., & Perez-Moreno, S. (2010). An assessment of the quality of a tourist destination: The case of Nerja, Spain. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 21(3), 269-289. [ Links ]

Maestro, R. M., Gallego, P. A., & Requejo, L. S. (2007). The moderating role of familiarity in rural tourism in Spain. Tourism Management, 28(4), 951-964. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2006.08.009 [ Links ]

Mangin, J. P. & Mallou, J. V. (2006). Modelización con estructuras de covarianzas en ciencias sociales: Temas esenciales, avanzados y aportaciones especiales. Coruña: Netbiblo. [ Links ]

Maslow, A. H. (1975). Motivación y Personalidad [Motivation and Personality]. Barcelona: Sagitario.

Mollá, A., Berenguer, G., Gómez, M., & Quintanilla, I. (2006). Comportamiento del consumidor. Barcelona: Editorial UOC. [ Links ]

Morley, C. L. (1998). A dynamic international demand model. Annals of Tourism Research, 25(1), 70-84. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(97)00067-4 [ Links ]

Ng, S. I., Lee, J. A., & Soutar, G. N. (2007). Tourists’ intention to visit a country: The impact of cultural distance. Tourism Management, 28(6), 1497-1506. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2006.11.005 [ Links ]

Pérez-Acosta, A. (2010). Análisis psicológico del posicionamiento publicitario una propuesta cuantitativa. Psicología desde el Caribe, 2-3, 39-46. [ Links ]

Pla, J. & León, F. (2008). Dirección de empresas internacionales. Madrid: Pearson Educación. [ Links ]

Prentice, R. (2004). Tourist familiarity and imagery. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(4), 923-945. [ Links ]

Rivas, J. A. & Esteban, I. G. (2004). Comportamiento del consumidor: decisiones y estrategia de marketing. Madrid: Esic Editorial. [ Links ]

Sabio, N., Kostin, A., Guillén-Gosálbez, G., & Jiménez, L. (2012). Holistic minimization of the life cycle environmental impact of hydrogen infrastructures using multi-objective optimization and principal component analysis. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 37(6), 5385-5405. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.09.039 [ Links ]

Sanchis, M. G. & Saura, I. G. (2006). Expectativas, satisfacción y lealtad en los servicios hoteleros. Un enfoque desde la cultura nacional. Papers de Turisme, 37-38, 7-25. [ Links ]

Schiffman, L. & Kanuk, L. L. (2010). Comportamiento del Consumidor (Décima ed.). (V. A. Ramírez, Trans.) México: Pearson Educación.

Soares, A. M., Farhangmehr, M., & Shoham, A. (2007). Hofstede's dimensions of culture in international marketing studies. Journal of Business Research, 60(3), 277-284. [ Links ]

Soler, I. P., & Gemar, G. (2017). A measure of tourist experience quality: the case of inland tourism in Malaga. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 1-14. doi: 10.1080/14783363.2017.1372185

Soler, I. P., Gemar, G., & Jimenez-Madrid, A. (2017). The impact of municipal budgets and land-use management on the hazardous waste production of Malaga municipalities. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 65, 21-28. [ Links ]

Sparks, B., & Pan, G. W. (2009). Chinese outbound tourists: Understanding their attitudes, constraints and use of information sources. Tourism Management, 30(4), 483-494. [ Links ]

Stryker, S. (1968). Identity salience and role performance: The relevance of symbolic interaction theory for family research. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 30(4), 558-5464. [ Links ]

Stryker, S. (1986). Identity theory: Development and extensions. In K. Yardley, & T. Honess (Eds.), Self and identity: Psychosocial perspective (Wiley, Trans., pp. 89-103). London. [ Links ]

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate statistics.Boston: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

Trompenaars, F., & Hampden-Turner, C. (2011). Riding the waves of culture: Understanding diversity in global business (Tercera ed.). Londres - Boston: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Turner, L. W., Reisinger, Y., & Witt, S. F. (1998). Tourism demand analysis using structural equation modelling. Tourism Economics, 4(4), 301-323. [ Links ]

Ueltschy, L. C., & Krampf, R. F. (2001). Cultural sensitivity to satisfaction and service quality measures. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 9(3), 14-31. [ Links ]

Yang, J., Yuan, B., & Hu, P. (2009). Tourism Destination Image and Visit Intention: Examining the Role of Familiarity. Journal of China Tourism Research, 5(2), 174-187. [ Links ]

Received: 14.07.2018

Revisions required: 15.11.2018

Accepted: 22.03.2019