Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.15 no.3 Faro set. 2019

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2019.150302

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

The effect of ruminative thought style and workplace ostracism on turnover intention of hotel employees: the mediating effect of organizational identification

O efeito do estilo de pensamento ruminativo e do ostracismo no local de trabalho na intenção de rotatividade de funcionários de hotéis: o efeito mediador da identificação organizacional

Nuray Turkoglu1, Ali Dalgic2

1Sinop University, Tourism Management Department, Turkey, nurayturkoglu@yahoo.com.tr

2Isparta University of Applied Sciences, Tourism Faculty, Turkey, alidalgic@mersin.edu.tr

ABSTRACT

The primary aim of this paper is to reveal the effects of the ruminative thought style and workplace ostracism on hotel employees’ turnover intention. In addition, the effect of the ruminative thought style and workplace ostracism on hotel employees’ turnover intention through the mediator role of organizational identification was investigated in this study. The data were collected by convenience sampling between 1 June and 1 October 2018 from the employees of the twelve 5-star hotel businesses in Bodrum, Turkey, yielding 432 valid survey forms. The results showed that ruminative thought style and workplace ostracism increase the turnover intention of hotel employees while organizational identification decreases it. In addition, organizational identification plays a mediating role between a ruminative thought style and turnover intention. Thus, we recommend to the managers that they should create a good working environment, support and participate in social activities with their team, make their employees feel that they are a part of the organization and always state that they value their team.

Keywords: Ruminative thought style, workplace ostracism, organizational identification, turnover intention.

RESUMO

O objetivo principal deste artigo é revelar os efeitos do pensamento ruminativo e do ostracismo no local de trabalho na intenção de rotatividade dos funcionários do hotel. Para além disso, foi investigado o efeito do estilo de pensamento ruminativo e do ostracismo no local de trabalho na intenção de rotatividade dos funcionários do hotel por meio do papel mediador da identificação organizacional. Os dados foram recolhidos por amostragem de conveniência entre 1 de junho e 1 de outubro de 2018 de entre os funcionários das doze empresas hoteleiras de cinco estrelas em Bodrum, Turquia, produzindo 432 questionários válidos. Os resultados mostraram que o estilo de pensamento ruminativo e o ostracismo no local de trabalho aumentam a intenção de rotatividade dos funcionários do hotel, enquanto a identificação organizacional a diminui. Além disso, a identificação organizacional desempenha um papel mediador entre um estilo de pensamento ruminativo e a intenção de rotatividade. Assim, recomendamos aos gerentes que criem um bom ambiente de trabalho, apoiem e participem nas atividades sociais com os seus colaboradores, façam com que estes se sintam parte da organização e afirmem que valorizam a sua equipa.

Palavras-chave: Estilo de pensamento ruminativo, ostracismo no local de trabalho, identificação organizacional, intenção de rotatividade.

1. Introduction

Since hotel businesses are labour intensive, human resources is an important factor. To avoid interruptions of operational activities, it is important to have qualified personnel who can provide quality services and create a competitive advantage (Tracey & Hinkin, 2008). In hotel businesses, however, qualified employees may not be enough to ensure positive outputs. Rather, creating harmony among work teams, providing socializing possibilities both inside and outside of the hotel, developing a good working environment for employees, and helping them to clear their minds of negative thoughts by building close contacts with them may be all needed to increase employee productivity. Thus, hotel managers must be aware of ruminative thought styles and workplace ostracism. The ruminative thought style involves individuals consistently thinking about the causes and consequences of their negative feelings (Michael, Halligan, Clark & Ehlers, 2007; Brinker & Dozois, 2009; Liverant, Kamholz, Sloan & Brown, 2011). Such individuals may have problems regarding their well-being, consistently experience tension in the workplace, have depressive moods and suffer high stress levels (Raley, 2010; Rosen & Hochwarter, 2014). Workplace ostracism, another important concept, occurs when an employee is ignored by a group or a team, is not invited to events organized inside and outside of the organization and is not spoken to. Employees who feel that they are ostracized may perform low performance, a tendency towards non-productive behaviors and intention to quit the organization (Leung, Wu, Chen & Young, 2011; Zhao, Peng & Sheard, 2013; Zheng, Yang, Ngo, Liu & Jiao, 2016).

Turnover intention may be further increased in employees who have both a ruminative thought style and are ostracized (Huang, 2007; Yang, 2008). Turnover intention is the last step before an individual actually quits the organization. Employees with a high turnover intention have already researched alternative employers and determined which business they would like to work for. In these circumstances, it is unrealistic to expect such employees to work productively, deliver high performance or provide quality services. If employees quit, the organization faces higher costs due to losing qualified personnel, searching for new employees and orienting for organization’s new members (Yang, 2008). In hotel businesses, the turnover intention of the employees increases for various reasons, such as business factors (management style, organizational culture, working environment, financial situation, etc.), salaries and promotion channels (inability to reach better-paid positions, lack of bonuses and promotions, etc.), personal feelings, the nature of hotel businesses, job content (information processing load, monotony, changing philosophy of job operations, etc.) (Yang, Wan & Fu, 2012). Personal feelings cause a ruminative thought style while the working environment and organizational culture can cause workplace ostracism. However, organizational identification may be an important factor in decreasing employee turnover intention. The turnover intention of the employees who assume themselves to be a part of the organization is lower (Harris & Cameron, 2005; Cole & Brunch, 2006; DeConinck, 2011).

If hotel managers and HR departments can solve personnel problems and keep individuals in the working team, their turnover intentions may be reduced. This requires determining the factors that may directly affect employees working performance and their well-being, and ensuring positive outcomes. In addition, according to the social identity theory, employees’ feelings about themselves as a part of the organization are important for reducing negative outcomes (Van Knippenberg & Hogg, 2001). In this study, we aimed to reveal the effects of ruminative thought styles, organizational ostracism perceptions and employee organizational identification on their turnover intentions in 5-star hotel businesses operating in Bodrum, Turkey. Another key objective is to reveal the mediating role of organizational identification on the combined effect of the ruminative thought style and workplace ostracism on turnover intention. It is hoped that this research will contribute to the tourism literature. It can be stated that it is important to present the ruminative thought style to both tourism academics and practitioners. Thus, it will be possible to contribute to the gap related to ruminative thinking in tourism literature. On the other hand, presenting workplace ostracism, which has the potential to create a psychological problem for employees, is another important issue. Therefore, it will be possible to present the organizational identification of the employees to the hotel managers. The next section presents an overview of the literature on ruminative thought style, workplace ostracism, organizational identification and turnover intention.

2. Literature review

2.1 Ruminative Thought Style

The ruminative thought style includes thoughts that are repetitive, difficult to control and unexpected. Individuals with a ruminative thought style tend to think repeatedly about the causes and results of negative happenings and/or negative feelings. Depressive symptoms occur as a result of negative events or emotions constantly occupying the minds of individuals and cause stress in individuals. (Michael, Halligan, Clark & Ehlers, 2007; Brinker & Dozois, 2009; Liverant, Kamholz, Sloan & Brown, 2011). In addition, they also experience problems with interpersonal communication (Evans & Segerstrom, 2011). Ruminative thoughts may arise due to incidents experienced by individuals as well as the loss of a close person. When individuals think about the reasons and results of the negativities they experience, this is termed “depressive rumination” while the thought style that causes the repetition of the agony and sadness arising from the loss of others and assets they value is called “grief rumination” (Eisma & Stroebe, 2017, pp. 59-60). In depressive rumination, feelings such as pessimism, exhaustion and anger are at the forefront, whereas feelings such as missing, guilt, anger, loneliness and anxiety may be observed in grief rumination (Eisma & Stroebe, 2017). To decrease the ruminative thought style, individuals must share the negativities they experience with others (Liverant, Kamholz, Sloan & Brown, 2011) and strive to resolve incidents clearly and acceptably instead of escaping from the incidents that cause the ruminative thoughts (Evans & Segerstrom, 2011).

In tourism businesses, employee well-being is important to provide a good service to guests. If employees are consistently visualizing the negativities they experience in their daily life or working environment, or trying to determine reasons for these, then service quality may decrease. Research in the relevant literature reveals this situation as well. Depressive mood is observed in employees with a ruminative thought style while workplace tension will increase (Rosen & Hochwarter, 2014), employee stress levels will rise (Raley, 2010), work performance will decrease (Rosen & Hochwarter, 2014) and emotional exhaustion will increase (Bisht, 2014). The turnover intention of hotel business employees increases when they experience depressive mood (Siu, Cheung & Lui, 2015), consistent workplace tension (Cropanzano, Howes, Grandey & Toth, 1997) and high-level stress (Huang, 2007; Yang, 2008).

2.2 Workplace Ostracism

Workplace ostracism involves an individual or a group ignoring, isolating or decreasing the social interaction opportunities of another individual (Ferris, Brown, Berry & Lian, 2008). Workplace ostracism generally involves not speaking to an employee or not inviting them to group activities (Robinson, O’Reilly & Wang, 2013). Ostracized individuals initially suffer from shock and emotional pain. However, they then evaluate the ostracism before concluding why they were ostracized (Williams, 2007). The second phase inevitably causes psychological problems and stress (Heaphy & Dutton, 2008). In addition, employees may need a sense of self and belonging (to a group or an organization) (Abrams & Hogg, 1988). When employees feel ostracized, their job dissatisfaction and turnover intention increase (Ferris, Brown, Berry & Lian, 2008; Balliet & Ferris, 2013; Scott & Duffy, 2015).

Hotel businesses rely on effective interaction and communication among the employees to provide good service. If one or more team members are ostracized, this may directly affect customer satisfaction. Workplace ostracism can raise the stress levels of employees (Chung, 2018), harm their service performance (Leung, Wu, Chen & Young, 2011) and increase counterproductive work behaviors (Zhao, Peng & Sheard, 2013). In addition, workplace ostracism can decrease employees’ tendency to help other employees while organizational citizenship behavior, which is an important factor, may disappear (Wu, Liu, Kwan & Lee, 2016). Among the ostracized employees, job satisfaction decreases (Fatima, 2016), and exhaustion and turnover intention increase (Ferris, Brown, Berry & Lian, 2008; Yin & Liu, 2013; Zheng, Yang, Ngo, Liu & Jiao, 2016).

2.3 Organizational Identification

Organizational identification is defined as “the degree to which employees define themselves by the same attributes that they believe define their organization” (Dutton, Dukerich & Harquail, 1994, p. 239). In an organization, those individuals who feel they are a part of a group and integrated have a high degree of organizational identification (Ashforth & Mael, 1989; Ellemers, De Gilder & Haslam, 2004). Such employees are affected by the successes and failures of the group or organization that they are a member of (Mael & Ashforth, 1992). They also spare significant time for their job tasks and responsibilities (Vallerand, Houlfort & Fores, 2003). Employees who feel like they are an integral part of the organization work more for the benefit of the organization (Ashforth & Mael, 1989). In addition, their job motivation and job performance increases (Qi & Ming-Xia, 2014).

The need for belonging may be observed in both personal and working lives. The perception of belonging to a workplace group or organization can increase employees’ intrinsic motivation (Van Knippenberg & Hogg, 2001). The more strongly employees believe that they belong to the business they work for, the greater organization identification will be. In hotel businesses, a high level of organizational identification is important. Organizational identification is a key factor for hotel employees to provide a quality service (Lu, Capezio, Restubog, Garcia & Wang, 2016). Moreover, employees with high level of organizational identification make more creative efforts (Brammer, He & Mellahi, 2015) and have high job satisfaction (Smidts, Pruyn & Van Riel, 2001). Finally, employees with organizational identification have weaker turnover intentions than others (Harris & Cameron, 2005; Cole & Brunch, 2006; DeConinck, 2011).

2.4 Turnover Intention

Turnover intention, which is the final step in the process of quitting a job, refers to employees’ searching for alternative jobs and not feeling they are a part of an organization (Tett & Meyer, 1993). Before revealing employee turnover intentions, specific psychological steps are present. The psychological steps that employees experience include evaluating the current organization or job, deciding whether they are satisfied with the organization and job, assessing alternative organizations in a possible turnover and comparing alternative jobs with the current one (Mobley, 1977). Employee turnover causes organizational costs. These include time spent and material resources used to find new employees, mistakes the new personnel may make while adapting to the job and training expenses (Yang, 2008). Turnover intention can harm the organization’s results and create individual problems for employees, such as stress, psychological problems and exhaustion (Dysvik & Kuvaas, 2010).

Since tourism businesses are labour intensive, human resources is one of the most important factors. The turnover of qualified employees has many organizational costs. Especially in high season, losing qualified personnel and trying to search for new personnel urgently may damage service quality (Choi, 2006). In addition, hotel businesses may lose competitive advantage and customer potential (Tracey & Hinkin, 2008: 14). Employee turnover intentions are increased by business factors (management style, organizational culture, working environment, financial situation, etc.), salaries and promotion channels (inability to reach better-paid positions, lack of bonuses and promotions, etc.), personal feelings, the nature of hotel businesses, and job content (information processing overload, monotony, changes to the philosophy of the job operations, etc.) (Yang, Wan & Fu, 2012). Hotel managers and human resources managers can reduce employee turnover intentions if they identify these problems in advance and try to solve them.

3. Hypotheses development

3.1 Ruminative Thought Style and Turnover Intention

According to response styles theory, the ruminative thought style maintains depressive affects. Consequently, if it is not treated, individuals may experience more severe depression. If individuals do not take active steps to change their ruminative thought styles, their minds will be preoccupied with the reasons and results of negative events (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1987; NolenHoeksema, 1991). Empirical research has shown that hotel employees with a ruminative thought style experience higher stress (Raley, 2010) which reduces their job performance and job satisfaction (Rosen & Hochwarter, 2014). Moreover, employee turnover intentions increase considering the matters specified (Huang, 2007; Yang, 2008). Based on response styles theory and the research literature, the following hypothesis has been formed;

H1: The ruminative thought style is positively related to turnover intention.

3.2 Workplace Ostracism and Turnover Intention

According to conservation of resources theory, individuals are motivated to create, develop and protect their own resources (items, job, respect, monetary resources, etc.) within the context of natural or acquired characteristics (Hobfoll, 2001). When individuals face the risk of losing their owned resources or actually lose them, their stress levels increase (Hobfoll, 2001; Zeidner, Ben-Zur & Reshef-Weil, 2011). Thus, the risk of ostracism or the ostracism itself increases the level of stress in individuals who face this behavior from other group members. Furthermore, the loss of critical factors like belonging, social exchange and respect, causes them to fear losing more resources (Zhu, Lyu, Deng & Ye, 2017). Such individuals may quit the group or organization. Empirical studies have shown that workplace ostracism increases the turnover intention of the affected employees (Ferris, Brown, Berry & Lian, 2008; Yin & Liu, 2013; Balliet & Ferris, 2013; Scott & Duffy, 2015; Zheng, Yang, Ngo, Liu & Jiao, 2016). Based on the conservation of resources theory and the research literature, the following hypothesis has been developed;

H2: Workplace ostracism is positively related to turnover intention.

3.3 Organizational Identification and Turnover Intention

According to social identity theory, individuals tend to place themselves in a specific category, such as a member of a group, religion or business, to meet their need for belonging (Ashforth & Mael, 1989). Thus, employees may consider their employers’ organization as their own business, thereby developing organizational identity. Such employees have high intrinsic motivation (Van Knippenberg & Hogg, 2001), which decreases turnover intention. Empirical research shows that organizational identification decreases turnover intention (Harris & Cameron, 2005; Cole & Brunch, 2006; DeConinck, 2011). Based on social identity theory and the research literature, the following hypothesis has been developed;

H3: The organizational identification is negatively related to turnover intention.

3.4 The Mediating Effect of Organizational Identification

The ruminative thought style, which means that employees consistently work with negative thoughts, may result in many individual and organizational negative outcomes. First, such employees experience raised stress levels (Raley, 2010), which in turn damages job performance and job satisfaction (Rosen & Hochwarter, 2014). Low job satisfaction may then encourage them to seek another job in a different business (Huang, 2007; Yang, 2008). High turnover of qualified employees may damage hotel business service quality and customer satisfaction. Therefore, it is important for managers to find solutions to their employees’ problems while making them believe they share the organization’s characteristics. When individuals identify with the organization they work in and feel a sense of belonging, they will experience fewer consistent negative feelings and thoughts, and lower turnover intentions (Harris & Cameron, 2005; Cole & Brunch, 2006; DeConinck, 2011). Social identity theory also posits that individuals’ need for belonging encourages them to be members of a specific group (Ashforth & Mael, 1989). Employees who feel that they are a member of the organization may therefore eliminate any negative feelings and thoughts more rapidly and thereby continue working in their current organization. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H4a: Organizational identification plays a mediating role in the relationship between ruminative thought style and turnover intention.

If colleagues isolate and ignore employees, and exclude them socially, then this indicates that they have been ostracized within the organization. An ostracized employee experiences increased stress levels (Heaphy & Dutton, 2008). This, alongside the resulting fear of losing other resources, can have both personal and organizational negative outcomes. According to conservation of resources theory, individuals are motivated to protect their owned resources (items, job, respect, monetary resources, etc.). Therefore, the loss of any of these resources causes stress (Hobfoll, 2001). This in turn increases their turnover intention (Ferris, Brown, Berry & Lian, 2008; Yin & Liu, 2013; Balliet & Ferris, 2013; Scott & Duffy, 2015; Zheng, Yang, Ngo, Liu & Jiao, 2016). Organizational identification may be an important factor in decreasing employee turnover intention. The employees, who perceive that their own characteristics match those of the organization and who consider the organization as a part of their identity, are more likely to remain in the organization even if they are ostracized by their colleagues (Harris & Cameron, 2005; Cole & Brunch, 2006; DeConinck, 2011). This leads to the following hypothesis:

H4b: Organizational identification mediates the relationship between workplace ostracism and turnover intention.

4. Meth odology

4.1 Sample and data collection

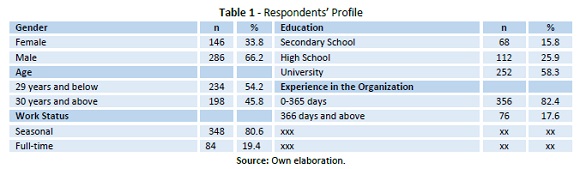

The research population was employees working at 5-star hotels in Turkey while the specific study population was individuals in the Aegean region because, apart from Antalya, it has the most 5-star hotels in Turkey (52 facilities in Muğla, 21 facilities in İzmir and 13 facilities in Aydın) after Antalya (Turizmaktuel, 2016; Kultur, 2016). Although this study population was more reachable than the general population, limited financial resources and manpower made it necessary to sample this population. The chosen sample was employees working at twelve 5-star hotel businesses in Bodrum (Mugla).

4.2 Measures

The measures in the survey form (except for the turnover intention) were translated into Turkish from the original English, and the consistency of the items with their originals was checked by back-translation with the help of academic experts (Brislin, 1970). Standard measures were used with 5point Likert scales (1 = Strongly disagree 5 = Strongly Agree). Ruminative thought style (20 items) was measured using the scale designed by Brinker and Dozois (2009) (α = 0.92; e.g. “I tend to replay past events as I would have liked them to happen.”, “Sometimes I realize I have been sitting and thinking about something for hours.”, “If I have an important event coming up, I can’t stop thinking about it.”). To measure perceived workplace ostracism (13 items), we used the scale developed by Ferris, Brown, Berry and Lian (2008) (α = 0.92; e.g. “I sit alone in a crowded lunchroom at work.”, “Others ignore me at work.”, “My coworkers don’t invite me when they go out for a coffee break.”). To measure organizational identification (6 items), we used the scale of Mael and Ashforth (1992) (α = 0.87; e.g. “When someone criticizes (name of organization), it feels like a personal insult.”, “When someone praises this organization, it feels like a personal compliment.”). Finally, we measured turnover intentions (4 items) using the scale developed by Akgündüz and Akdağ (2014) (α = 0.81; e.g. “I often think about leaving this hotel.”, “I will probably be looking for another job soon.”).

4.3 Limitations and future research

This study inevitably has some limitations. The most important is the sampling method. Since reaching all individuals in the determined population was nearly impossible in terms of material and human resources, convenience sampling was preferred. However, this method may create some problems for generalizing the study results, so future studies may provide more reliable results through quota sampling. In addition, this study was limited to Turkey’s Aegean region, which may not be representative of hotel employees throughout Turkey or internationally.

5. Data analysis

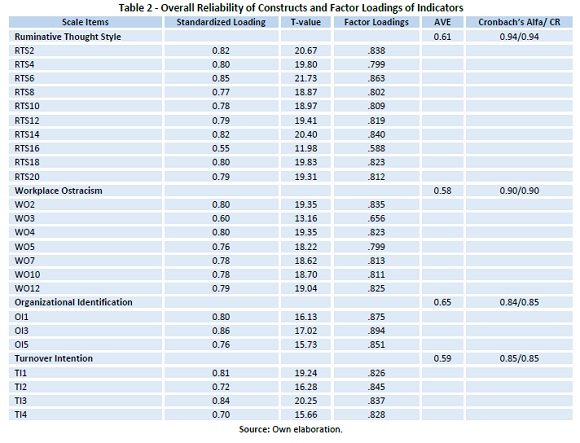

To test the structural validity of the measures used, descriptive and confirmatory factor analyses were conducted. For the descriptive factor analysis, we decided that the eigenvalue must be greater than 1 with a load of at least 0.500 (Hair, Black, Babin & Anderson, 2010) while the load difference between any two factors must be at least 0.100 in case of overlapping and Varimax conversion must be applied. The ruminative thought style measure KMO value was 0.951 while the Bartlett Test of Sphericity was meaningful (x²=3066.744; p<0.001). After

descriptive factor analysis, three items were excluded since they had factor loads below 0.500. The remaining items grouped under a single dimension and explained about 65% of the total variance. The workplace ostracism measure KMO value was 0.915 while the Bartlett Test of Sphericity result was meaningful (x²=1659.744; p<0.001). Four items with factor loads less than 0.500 were excluded from further analyses. The remaining items were grouped under a single dimension and explained about 64% of the total variance. The KMO value of the organizational identification measure was 0.721 while the Bartlett Test of Sphericity result was meaningful (x²=542.072; p<0.001). Two items with factor loads less than 0.500 were excluded from further analyses. The remaining items grouped under a single dimension and explained about 76% of the total variance. The KMO value of the turnover intention measure was 0.715 while the Bartlett Test of Sphericity result was meaningful (x²=877.137; p<0.001). All four items grouped under a single factor and explained about 70% of the total variance.

To determine the dimensions obtained by the descriptive factor analysis and prove the validity of the model theoretically, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted (Hair, Black, Babin & Anderson, 2010). Before the confirmatory factor analysis was performed, several specific assumptions were considered. The measure items’ standardized values had to be greater than 0.50 (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson & Tatham, 2006) and the t-values greater than ±1.96 (Schumacker & Lomax, 2004). In addition, the average variance extracted (AVE) value must be 0.50 (Hair, Black, Babin & Anderson, 2010) while the composite reliability (CR) value must be greater than 0.70 (Hair, Black, Babin & Anderson, 2010). According to the confirmatory factor analysis, the standardized values of one item in the ruminative thought style and workplace ostracism scales were below 0.50, so both items were excluded from further analyses. The t-values of the measures were greater than ±1.96, so they were included in the analyses. After examining, the output file, some modifications were implemented. This made it possible to identify similar items or perceived as similar by the participants, and to make the model theoretically suitable. After all the modifications, the ruminative thought style measure had 10 items, the workplace ostracism measure had 7 items and the turnover intention measure had 4 items. The AVE values of all measures were greater than 0.50 while the CR values were greater than the threshold. In addition, regarding model goodness of fit values, the normalized Chi-Square was 5.52, RMSEA was 0.10, AGFI was 0.82, GFI was 0.85, SRMR was 0.055, CFI was 0.96 and NFI was 0.95. Although some goodness of fit values exceeded the reference values, we judged that the measurement model was theoretically compliant.

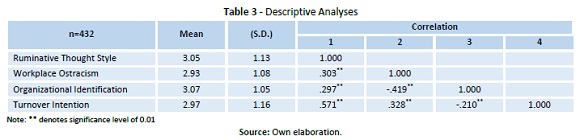

Table 3 presents the correlations, means and standard deviations of the variables. There was a significant and positive association between ruminative thought style and workplace ostracism (r= 0,303; p˂0,001), and between organizational identification (r= 0,297; p˂0,001) and turnover intention (r= 0,571; p˂0,001). Workplace ostracism also had a significant and negative correlation with organizational identification (r= - 0,419; p˂0,001) and a significant and positive association with turnover intention (r= 0,328; p˂0,001). Finally, there was a significant and negative association between organizational identification and turnover intention (r= -0,210; p˂0,001).

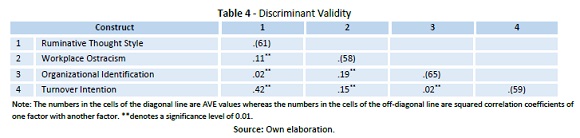

Table 4 presents the distinguishing validity results, which show how well the model distinguishes between factors (specifying the differentiation) (Hair, Black, Babin & Anderson, 2010). The AVE values belonging to the variables in parentheses had to be greater than the square of the correlation coefficients between the variables (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The results indicate that distinguishing validity was achieved between the dimensions.

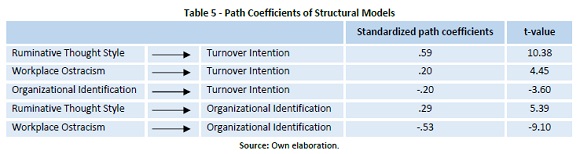

To test the hypotheses, a path analysis was conducted using structural equity modeling. This demonstrated a significant and positive association between ruminative thought style and turnover intention (β= 0.59; p≤0.001). In addition, there was a significant and positive association between workplace ostracism and turnover intention (β= 0.20; p≤0.001). Finally, organizational identification had a significant and negative effect on turnover intention (β= -0.20; p≤0.001). Thus, H1, H2 and H3 were all supported.

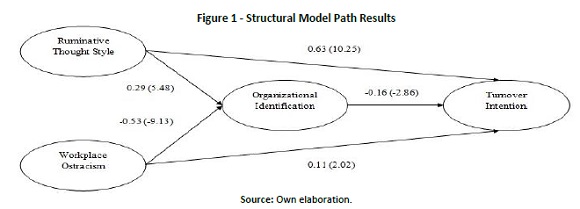

Figure 1 presents the path analysis results of the implemented model. These results indicate that ruminative thought style both directly (β= 0.63) and indirectly affects turnover intention via organizational identification (β=0.29*-0.16=-0.046). Since the indirect effect (β=-0.046) is weaker than the direct effect (β=0.63), we can conclude that organizational identification partially mediates the effect of ruminative thought style on turnover intention. Thus, H4a was partially supported.

Furthermore, workplace ostracism both directly affects turnover intention (β= 0.11) and indirectly affects it through organizational identification (β=-0.53*-0.16=0.084). Since the indirect effect (β=0.084) is weaker than the direct effect (β=0.11), we can conclude that organizational identification partially mediates the effect of workplace ostracism on turnover intention. Thus, H4b was partially supported.

6. Conclusion

The first hypothesis - where employees with ruminative thought styles have higher turnover intentions - was supported since such thought styles significantly increased their turnover intentions. The second hypothesis - where workplace ostracism increases turnover intentions - was also supported since employees reporting ostracism by their colleagues had significantly higher turnover intentions. The third hypothesis - where organizational identification decreases employee turnover intentions - was also supported. That is, those employees who used the hotel business to meet their need for belonging had significantly lower turnover intentions. Finally, the fourth hypothesis - where organizational identification mediates the effects on turnover intention of both ruminative thought style and workplace ostracism on was supported because there were significant partial mediating effects in both cases.

6.1 Theoretical Contributions

These findings provide an important contribution to the hospitality literature. First, the turnover intentions of hotel employees with a ruminative thought style are high while stress levels of hotel employees with consistent negative feelings and thoughts increase, making them more willing to quit their organizations, based on response styles theory (Raley, 2010; Rosen & Hochwarter, 2014), and confirmed by empirical research (Huang, 2007; Yang, 2008). The fact that the hotel staff is constantly trying to find the cause of the negativity and not being able to overcome their negative thoughts will cause them to continue their business life in a depressive mode. In such a case, it will cause service errors in hotel businesses, which are already largely based on people's communication and interaction, and will cause the hotel businesses to make great efforts for service compensation. In addition, it can be said that the employee who has a ruminative thinking style may have difficulty in meeting the expectations of the customers. Customer complaints may increase. This will increase the turnover intention by decreasing the commitment of the person who has a ruminative thinking style with increased stress level.

Secondly, workplace ostracism, which increases stress, affects personal feelings and may cause both personal and organization negative outcomes. Hotel employees suffering from workplace ostracism lose self-respect and sympathy, according to conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll, 2001; Zeidner, Ben-Zur & Reshef-Weil, 2011). Hotel employees who lose their social environment will consider quitting the organization as a remedy to avoid losing further owned resources, as confirmed by empirical research (Ferris, Brown, Berry & Lian, 2008; Yin & Liu, 2013; Balliet & Ferris, 2013; Scott & Duffy, 2015; Zheng, Yang, Ngo, Liu & Jiao, 2016). If the employee does not feel like a member of the group and feels excluded by colleagues, then it is usual the turnover intention will increase.

Finally, hotel employees may use their work to meet their need for belonging, according to social identity theory (Ashforth & Mael, 1989). That is, hotel employees may consider a group or the hotel itself as a part of their social identity to meet their need for belonging. The degree that they perceive the organizational characteristics to match their own and that they consider the place they work as their workplace determines their level of organizational identification (Van Knippenberg & Hogg, 2001). Hotel employees with a high level of organizational identification have lower turnover intention, according to social identity theory and confirmed by empirical research (Harris & Cameron, 2005; Cole & Brunch, 2006; DeConinck, 2011). It can be stated that if the personality and characteristics of the employees do not coincide with the aims of the businesses, the employees may turn to different business alternatives. In this case, it may be necessary to allow employees to shape their own business processes according to their own characteristics and to give a certain level of autonomy in performing their jobs in order to reduce the turnover intention.

We found that organizational identification is a partial mediator of the effect of both ruminative thought style and workplace ostracism on turnover intention. Personal feelings, working environment and organizational culture all affect the turnover intentions of hotel employees (Yang, Wan & Fu, 2012). Despite negative personal feelings, negative behaviors of colleagues and an anti-social organizational culture, a high level of organizational identification may help employees stay in the organization. Evaluated according to social identity theory, this implies that if the organization meets the need for belonging of hotel employees, then this may decrease their negative feelings and thoughts, and thereby reduce turnover intention (Van Knippenberg & Hogg, 2001). Thus, organizational identification appears to be an important mediator of the effect of ruminative thought style on turnover intention, although organizational identification is not the only variable determining this effect (partial mediator). This also applies to the mediating role of organizational identification on the effect of workplace ostracism on turnover intention. If hotel employees identify themselves with the hotel business, they may stay in the organization despite ostracism by their colleagues (Yin & Liu, 2013; Balliet & Ferris, 2013; Zheng, Yang, Ngo, Liu & Jiao, 2016).

6.2 Practical Implications

We found that hotel employees with a ruminative thought style have higher turnover intentions. Thus, they are more likely to quit the organization. To prevent this, hotel managers and human resources officers must clearly learn about employees’ problems. In hotel businesses, managerial and even collegial support may help hotel employees eliminate negative feelings and thoughts (Evans & Segerstrom, 2011). On the other hand, it is important for hotel managers to identify people who have ruminative thinking in the recruitment phase. Persons with ruminative thinking can be identified through written tests in recruitment. In this way, it may be possible to prevent problems that may occur in organizational terms before they begin.

We also found that workplace ostracism is an important determiner of turnover intention for these hotel employees. If the hotel employee is isolated, ignored and not greeted by other individuals in the organization, they may quit. This directly damages service quality and customer satisfaction due to the loss of a qualified employee. If hotel managers organize social activities with team members, join them during breaks, chat with them and try to build an intimate working environment within the organization, then they may decrease turnover intentions and retain qualified employees within the organization (Ferris, Brown, Berry & Lian, 2008). Another suggestion may be to create social spaces within the employees of the enterprise and to design these spaces so that they can spend time with each other. Employees can increase their relationships with colleagues during work breaks.

Organizational identification decreases hotel employees’ turnover intention. That is, hotel employees who deem the organization they work a part of their identity stay in the organization to meet their need for belonging. Hotel managers and their colleagues should therefore increase this organizational identification. This is more likely if the hotel managers state that the characteristics of the employee and the organization match, prepare a socially positive working environment and build close relations with hotel employees. Similarly, if the colleagues of the hotel employee accompany them on social activities and create a positive workplace atmosphere, the organizational identification of the employee will increase, thereby reducing their turnover intention (Van Knippenberg & Hogg, 2001).

Finally, we found that organizational identification mediates the effects of a ruminative thought style and perceived workplace ostracism on hotel employee turnover intentions. Both the ruminative thought style and workplace ostracism are important initial variables that increase turnover intentions, and both damage employee well-being and raise their stress levels (Heaphy & Dutton, 2008; Raley, 2010). Therefore, hotel managers must ensure that the characteristics of the hotel business and the hotel employee match, and try to make them consider the organization a part of their social identity to diminish the negative effects of the ruminative thought style and workplace ostracism. The organizational identification of the hotel employees will increase if hotel managers ensure that each hotel employee feels like a part of the business.

REFERENCES

Abrams, D. & Hogg, M. A. (1988). Comments on the motivational status of self-esteem in social identity and intergroup discrimination. European Journal of Social Psychology, 18(4), 317-334. [ Links ]

Akgündüz, Y. & Akdag, G. (2014). The effects of personality traits of employees on core self-evaluation and turnover intention. Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart Univ. J. Admin. Sci. 12 (24), 295-318. [ Links ]

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20-39. [ Links ]

Balliet, D. & Ferris, D. L. (2013). Ostracism and prosocial behavior: A social dilemma perspective. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 120(2), 298-308. [ Links ]

Bisht, N. S. (2014). Role ambiguity, role conflict and burnout: The mediating role of rumination in higher education faculty. Research and Sustainable Business Congress. 422-430. ISBN: 978-93-83842-19-3.

Brammer, S., He, H., & Mellahi, K. (2015). Corporate social responsibility, employee organizational identification, and creative effort: The moderating impact of corporate ability. Group & Organization Management, 40(3), 323-352. [ Links ]

Brinker, J. K. & Dozois, D. J. (2009). Ruminative thought style and depressed mood. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(1), 1-19. [ Links ]

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translationforcross-culturalresearch. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185-216. [ Links ]

Choi, K. (2006). A structural relationship analysis of hotel employees' turnover intention. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 11(4), 321-337. [ Links ]

Chung, Y. W. (2018). Workplace ostracism and workplace behaviors: A moderated mediation model of perceived stress and psychological empowerment. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 31(3), 304-317. [ Links ]

Cole, M. S., & Bruch, H. (2006). Organizational identity strength, identification, and commitment and their relationships to turnover intention: Does organizational hierarchy matter?. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(5), 585-605. [ Links ]

Cropanzano, R., Howes, J. C., Grandey, A. A. & Toth, P. (1997). The relationship of organizational politics and support to work behaviors, attitudes, and stress. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 18(2), 159-180. [ Links ]

DeConinck, J. B. (2011). The effects of leader-member exchange and organizational identification on performance and turnover among salespeople. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 31(1), 21-34. [ Links ]

Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., & Harquail, C. V. (1994). Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 239-263. [ Links ]

Dysvik, A. & Kuvaas, B. (2010). Exploring the relative and combined influence of mastery-approach goals and work intrinsic motivation on employee turnover intention. Personnel Review, 39(5), 622-638. [ Links ]

Eisma, M. C. & Stroebe, M. S. (2017). Rumination following bereavement: An overview. Bereavement Care, 36(2), 58-64. [ Links ]

Ellemers, N., De Gilder, D., & Haslam, S. A. (2004). Motivating individuals and groups at work: A social identity perspective on leadership and group performance. Academy of Management Review, 29(3), 459-478. [ Links ]

Evans, D. R. & Segerstrom, S. C. (2011). Why do mindful people worry less?. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 35(6), 505-510. [ Links ]

Fatima, A. (2016). Impact of workplace ostracism on counter productive work behaviors: Mediating role of job satisfaction. Abasyn University Journal of Social Sciences, 9(2).

Ferris, D. L., Brown, D. J., Berry, J. W. & Lian, H. (2008). The development and validation of the Workplace Ostracism Scale. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1348. [ Links ]

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 39-50. [ Links ]

Gefen, D. & Ridings, C. M. (2002). Implementation team responsiveness and user evaluation of customer relationship management: A quasiexperimental design study of social exchange theory. Journal of Management Information Systems, 19(1), 47-69. [ Links ]

Hair, J. F. Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J. & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: PrenticeHall

Hair, J. F., Black, W. O., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E. & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis a global perspective. New Jersey: Pearson. [ Links ]

Harris, G. E., & Cameron, J. E. (2005). Multiple dimensions of organizational identification and commitment as predictors of turnover intentions and psychological well-being. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 37(3), 159. [ Links ]

Heaphy, E. D. & Dutton, J. E. (2008). Positive social interactions and the human body at work: Linking organizations and physiology. Academy of Management Review, 33(1), 137-162. [ Links ]

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology An International Review, 50(3), 337-421. [ Links ]

Huang, H. I. (2007). Understanding culinary arts workers: Locus of control, job satisfaction, work stress and turnover intention. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 9(2-3), 151-168. [ Links ]

Kultur (2016). yigm.kulturturizm.gov.tr/.../53370,isletme-ve-yatirim-belgeli-tesis-istatistikleri-2016xl Access date: 15 September 2017. [ Links ]

Leung, A. S., Wu, L. Z., Chen, Y. Y. & Young, M. N. (2011). The impact of workplace ostracism in service organizations. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30(4), 836-844. [ Links ]

Liverant, G. I., Kamholz, B. W., Sloan, D. M. & Brown, T. A. (2011). Rumination in clinical depression: A type of emotional suppression?. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 35(3), 253-265. [ Links ]

Lu, V. N., Capezio, A., Restubog, S. L. D., Garcia, P. R., & Wang, L. (2016). In pursuit of service excellence: Investigating the role of psychological contracts and organizational identification of frontline hotel employees. Tourism Management, 56, 8-19. [ Links ]

Mael, F., & Ashforth, B. E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13(2), 103-123. [ Links ]

Michael, T., Halligan, S. L., Clark, D. M. & Ehlers, A. (2007). Rumination in posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 24(5), 307-317. [ Links ]

Mobley, W. H. (1977). Intermediate linkages in the relationship between job satisfaction and employee turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 62(2), 237. [ Links ]

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1987). Sex differences in unipolar depression: evidence and theory. Psychological Bulletin, 101(2), 259. [ Links ]

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 569. [ Links ]

Peng, A. C. & Zeng, W. (2017). Workplace ostracism and deviant and helping behaviors: The moderating role of 360 degree feedback. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(6), 833-855. [ Links ]

Qi, Y. & Ming-Xia, L. (2014). Ethical leadership, organizational identification and employee voice: examining moderated mediation process in the Chinese insurance industry. Asia Pacific Business Review, 20(2), 231-248. [ Links ]

Qian, J., Yang, F., Wang, B., Huang, C. & Song, B. (2017). When workplace ostracism leads to burnout: The roles of job selfdetermination and future time orientation. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1-17.

Raley, A. B. (2010). Can't get it out of my head: The role of gender in the relations between ruminative styles, negative affect, and stress behaviors (Doctoral dissertation, Rice University). [ Links ]

Robinson, S. L., O’Reilly, J. & Wang, W. (2013). Invisible at work: An integrated model of workplace ostracism. Journal of Management, 39(1), 203-231. [ Links ]

Rosen, C. C. & Hochwarter, W. A. (2014). Looking back and falling further behind: The moderating role of rumination on the relationship between organizational politics and employee attitudes, well-being, and performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 124(2), 177-189. [ Links ]

Schumacker, R. E. ve Lomax, R. G. (2004). A beginner's guide to structural equation modeling. Psychology Press.

Scott, K. L. & Duffy, M. K. (2015). Antecedents of workplace ostracism: New directions in research and intervention. In Mistreatment in Organizations (pp. 137-165). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [ Links ]

Siu, O. L., Cheung, F. & Lui, S. (2015). Linking positive emotions to work well-being and turnover intention among Hong Kong police officers: The role of psychological capital. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(2), 367-380. [ Links ]

Smidts, A., Pruyn, A. T. H., & Van Riel, C. B. (2001). The impact of employee communication and perceived external prestige on organizational identification. Academy of Management Journal, 44(5), 1051-1062. [ Links ]

Tett, R. P. & Meyer, J. P. (1993). Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention and turnover: Path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Personnel Psychology, 46(2), 259-293. [ Links ]

Turizmaktuel (2016). http://www.turizmaktuel.com/haber/turkiye-de-kac-tane-5-yildizli-otel-var . Access date: 15 October 2018. [ Links ]

Tracey, J. B. & Hinkin, T. R. (2008). Contextual factors and cost profiles associated with employee turnover. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 49(1), 12-27. [ Links ]

Vallerand, R. J., Houlfort, N., & Fores, J. (2003). Passion at work. Emerging perspectives on values in organizations, 175-204. [ Links ]

Van Knippenberg, D., & Hogg, M. A. (2001). Social identity processes in organizations. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 4(3), 185-189. [ Links ]

Williams, K. D. (2007). Ostracism. Annual Review of Psychology, 58. [ Links ]

Wu, C. H., Liu, J., Kwan, H. K. & Lee, C. (2016). Why and when workplace ostracism inhibits organizational citizenship behaviors: An organizational identification perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(3), 362. [ Links ]

Yang, J. T. (2008). Effect of new comersocialisation on organisational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover intention in the hotel industry. The Service Industries Journal, 28(4), 429-443. [ Links ]

Yang, J. T., Wan, C. S., & Fu, Y. J. (2012). Qualitative examination of employee turnover and retention strategies in international tourist hotels in Taiwan. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(3), 837-848. [ Links ]

Yin, K. & Liu, Y. R. (2013). Workplace ostracism and turnover intention: The roles of organizational identification and career resilience. Soft Science, 27(4), 121-124. [ Links ]

Zeidner, M., Ben-Zur, H. & Reshef-Weil, S. (2011). Vicarious life threat: An experimental test of Conservation of Resources (COR) theory. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 641-645. [ Links ]

Zhao, H., Peng, Z. & Sheard, G. (2013). Workplace ostracism and hospitality employees’ counterproductive work behaviors: The joint moderating effects of proactive personality and political skill. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 33, 219-227. [ Links ]

Zheng, X., Yang, J., Ngo, H. Y., Liu, X. Y. & Jiao, W. (2016). Workplace ostracism and its negative outcomes. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 15(4), 143-151. [ Links ]

Zhu, H., Lyu, Y., Deng, X. & Ye, Y. (2017). Workplace ostracism and proactive customer service performance: A conservation of resources perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 64, 62-72. [ Links ]

Received: 15.01.2019

Revisions required: 16.03.2019

Accepted: 21.04.2019