1. Introduction

1.1 Rationale and research background

Cultural entrepreneurship is a relatively new discipline in management and cultural studies. The concept was introduced by Paul Dimaggio in 1982. He defines this practice as 'the creation of an organisational form that members of the elite could control and govern' (Dimaggio, 1982, p. 35) and analyses the processes of forming institutions of high culture in the 19th century Boston. In the next 20 years, little attention was paid to the specific practice of entrepreneurship in culture and the arts. However, the interest in cultural entrepreneurship has been increasing since the 2000s. At the present moment, we can determine two main avenues of the perception of cultural entrepreneurship. The first one is entrepreneurial activities in the fields of cultural and creative industries and the arts. In this sense, culture is perceived as a sector, and the focus is on economic and social forms which are defined as the cultural sector (Spilling, 1991), i.e. cultural industries, creative industries, and traditional arts. The second perception of cultural entrepreneurship views culture as an aspect of all sectors, and the focus is on how entrepreneurs deploy cultural resources for the legitimation of their ventures (Gehman & Soublière, 2017). This paper looks into the narrow approach to cultural entrepreneurship, which considers the entrepreneurial practices in the cultural sector and offers the first systematic review of research on the topic.

Cultural entrepreneurship can be defined as the specific activity of establishing cultural businesses and bringing to market cultural and creative products and services that encompass a cultural value but also have the potential to generate financial revenues. Most of the academic literature is primarily focused on the specific characteristics of cultural entrepreneurs and their motivation to start their ventures. The publications cover a wide range of subsectors. However, different definitions and the scope of cultural and creative industries make their distinction difficult to determine. In general, culture as a sector includes a wide set of subsectors, e.g. traditional arts (performing arts, visual arts, and classical music), cultural heritage, film, DVD and video, music, radio and television, books and press, new media, photography, architecture, design, digital arts, and videogames (COM (2010) 183 Final). In the last five years, the interest in the business models employed by cultural entrepreneurs, public policies for stimulating these practices, and the role of cultural entrepreneurship for urban development is growing (Metze, 2009; Phillips, 2010; Lindkvist, 2013; Ratten & Ferreira, 2017). Besides, the need for implementing cultural entrepreneurship as an academic discipline, it has been recognised as an essential tool for boosting cultural and creative industries (Rae, 2004; Carey & Naudin, 2006; Gangi, 2015).

The focus of the paper is on the evolvement of the academic literature in regards to entrepreneurship in cultural industries, creative industries, and the arts. The contribution of the paper is in the comprehensive summary of relevant publications in the field of cultural entrepreneurship, published in Scopus, the critical evaluation of the state of the research and the identification of future research directions.

1.2. Purpose

This paper sets two primary goals. Firstly, it aims at providing a comprehensive review of research on entrepreneurship in cultural and creative industries, and the arts by using the Scopus database to adjudicate where the field is going and what ground it covers. Secondly, based on the performed analysis of available publications, this paper will identify research gaps and give directions for future research.

2. Methodology

2.1. Data collection

The data collection was performed from November 2019 to January 2020. The Scopus database served as the main source of data. Only publications in the English language were considered. The authors implemented an extensive search in the database by using a combination of keywords in the title, abstract, and keywords of the publications:

Search words 1: 'Cultural entrepreneurship' - results: 123

Search words 2: 'Arts entrepreneurship' - results: 49

Search words 3: 'Entrepreneurship' and 'cultural industries' - results: 32

Search words 4: 'Entrepreneurship' and 'creative industries' - results: 41

Search words 5: 'Entrepreneurship in the arts' - results: 4

Search words 6: 'Creative entrepreneurship' - results: 167

The search resulted in 416 publications. Twenty-seven of them were not in the English language, and 59 were duplicates. The authors read the titles and abstracts of all publications, which had appeared in the search results. If a paper was considered relevant for the research, the full text was obtained. The criteria for relevancy included: the publication to be theoretical or empirical research on entrepreneurial practices in the field of the arts, cultural and creative industries. In that way, the research on the culture of entrepreneurs (as a behavioural phenomenon); publications, in which cultural entrepreneurship is only mentioned, without investigating the topic, or considering creativity as an independent skill or ability, were not included in the final dataset. The paper does not examine cultural entrepreneurship as defined by Lounsbury and Glynn (2001), as the process of storytelling that functions to identify and legitimate new ventures, because it falls outside the entrepreneurial practices in cultural industries, creative industries, and the arts, except if these sectors are the subject of the research.

The final dataset included 131 relevant publications, listed in Appendix 1, starting from the first one in the field by Dimaggio (1982) to the most recent ones available in Scopus until the end of 2019. Only the most important and relevant publications are cited throughout the paper.

2.2 Data analysis

Data analysis included quantitative and qualitative thematic analysis of publications. The quantitative data analysis involved frequencies, cross-tabulations, and Chi-square test to identify differences in the distribution patterns of publications by a period of publication. For every publication in the dataset, the following characteristics were retrieved to be used for the analysis: type of publication (conference paper, journal article, book chapter or book), publication year, and full reference. The full text of the publication was read, and the paper was classified in the following categories:

Sector focus - the authors identified three main categories (cultural industries, creative industries, and the arts), in which the authors of a publication relate their research and whether there is a focus on one specific sector in these categories. One publication can be classified in more than one category because of the different scope of cultural and creative industries in nation-states. For instance, in the U.K., the term 'creative industries' is primarily used and covers the domain of cultural industries and the arts.

Research methodology - research approach applied in the publication. Two categories are used: empirical or conceptual research.

Country of focus - the country in which data was collected, if empirical research was conducted.

Research domain - the qualitative thematic analysis identified eight broad research domains of the topics of publications: 1) Characteristics and motivation of entrepreneurs, 2) Business models, 3) Audience development, 4) Use of information and communication technologies, 5) Urban development, 6) Public policy, 7) Incubators and clusters and 8) Entrepreneurial education. The domains were not predetermined before the start of the analysis but rather emerged during the thematic analysis of the papers.

3. Findings

This section presents the quantitative and qualitative results of the study. Although the research domains emerged during the thematic analysis of the papers, the presentation of findings will start with the quantitative results because they provide a general overview of the findings, similar to previous studies (e.g. Ivanov et al., 2019). The qualitative findings will delve deeper into the analysis of publications by the research domain.

3.1. Quantitative analysis - general overview

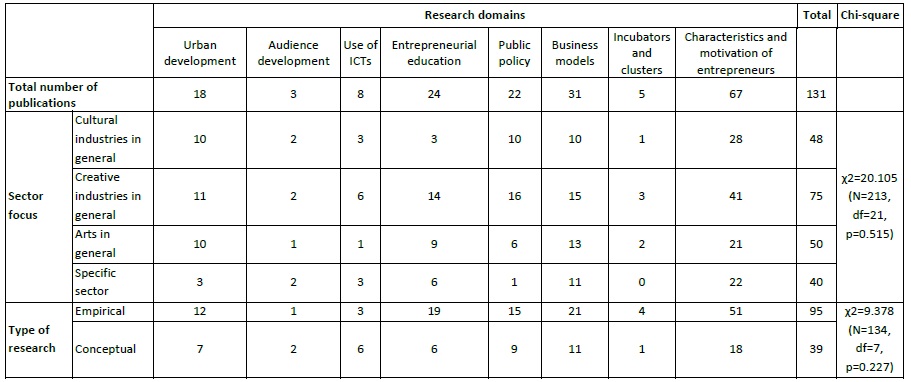

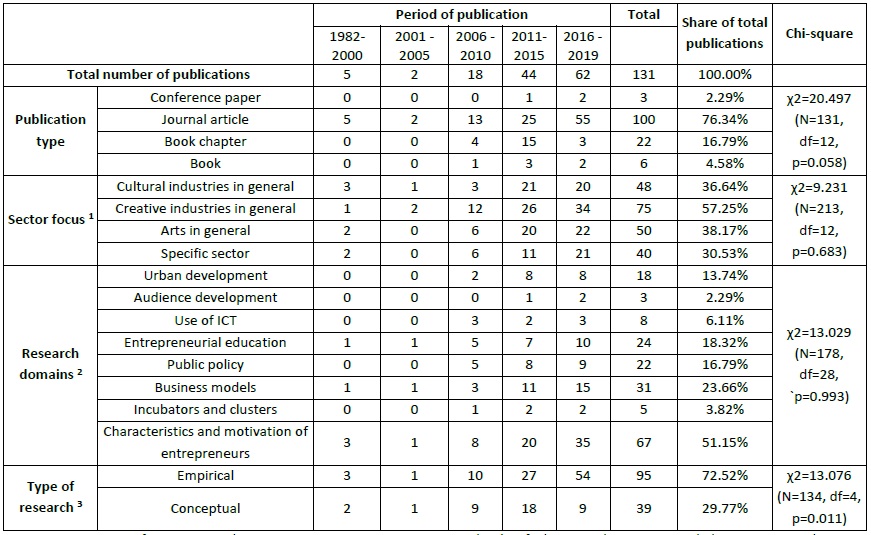

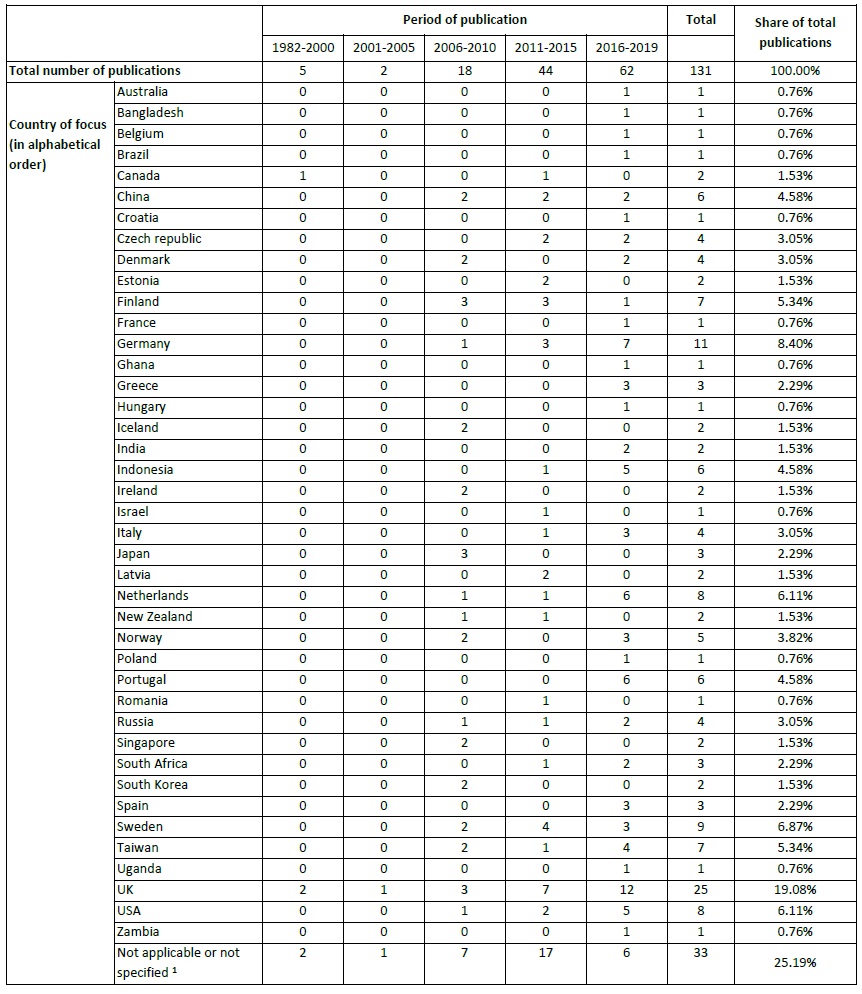

Tables 1-3 present the quantitative results of the research. Table 1 indicates that while cultural entrepreneurship has received little attention until the end of the 20th century with only four papers in the field, it has gained momentum after 2001. 62 out of 131 papers in the field (that is 47.3%) were published in the last four years (i.e. since 2016), clearly indicating the importance of cultural entrepreneurship as a research field. Journal articles dominate the types of publications (76.3% of all publications). Looking at the sector focus, we see that creative industries received slightly greater attention (57.3% of the papers) compared to the arts (38.2%) and cultural industries (36.6%), while 30.5% of the papers deal with a specific sector (e.g. film, music, videogames, performing arts, fashion). Empirical papers predominate (72.5%) compared to conceptual ones, especially since 2011 (χ2=13.076, N=134, df=4, p=0.011 - see Table 1), while most of them (19.1%) have the U.K. as an empirical context (see Table 2). Cultural entrepreneurship has also attracted the attention of researchers not only in Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, and the USA but also in less developed countries such as Uganda and Zambia (one paper for each country). As a whole, the geographic coverage of publications is quite broad and includes 41 countries (Table 2). Concerning the research domain, much of the research has been directed towards the 'Characteristics and motivation of entrepreneurs' (67 out of 131 publications), 'Business models' (31 papers), and 'Entrepreneurial education' (24 papers). 'Public policy' (22 papers) and 'Urban development' (18 papers) have received less attention, while 'Use of information and communication technologies' (8 publications), 'Incubators and clusters' (5 papers), and 'Audience development' (3 papers) have been largely neglected. No significant differences were found in the distribution of publications in the various research domains by sector focus or type of research (Table 3).

Table 1 Number of publications by a period of publication, type of publication, sector focus, research domain, and type of research

Notes: 1. One paper can focus on more than one tourism sector; 2. One paper can be classified in more than one research domain; 3. More than one type of research can be applied in a book.

Table 2 Number of publications by a period of publication and country of focus

Notes: 1. Not applicable (if conceptual paper) or not specified (if empirical paper but the country is not mentioned); 2. One paper can have an empirical focus on more than one country.

3.2 Qualitative thematic analysis of research domains

The qualitative thematic analysis identified eight research domains in the field of cultural entrepreneurship that are elaborated below. Each publication is analysed in relation to one or more research domains depending on its focus.

3.2.1 Characteristics and motivation of entrepreneurs

The characteristics and motivation of cultural entrepreneurs seem to be the most prominent theme among scholars. Paul Dimaggio published the earliest article on cultural entrepreneurship, in which he introduces the new figure of the cultural capitalist - a person who invests the profits gained through the management of industrial enterprises for the foundation and maintenance of a cultural institution (DiMaggio, 1982). Until recently, little attention has been devoted to the formation of this new economic and cultural actor who takes the risk of starting a cultural enterprise. The academic interest in the figure of the cultural entrepreneur has gradually risen mainly because of the revealed potential of cultural and creative industries as economically important sectors. Furthermore, the creative dimension of this type of entrepreneurship is gradually entering the academic discourse (Mazzoni & Lazzeretti, 2018).

Cultural entrepreneurs seem to be different in comparison to those in other economic sectors. The difference is in contextual and sectoral features, the nature of artistic work, and specific cultural values employed by cultural entrepreneurs. Klamer (2011) determines that the creative process is the 'moral attribute' of the cultural entrepreneurs, while economics is only an instrument for realising cultural values. For Scott (2012) the term' cultural entrepreneur' is understood as the combination of three elements: creating new cultural products, orientation towards accessing opportunities to produce an identity and social trajectory, and finding ways of doing so without significant economic resourses. The most distinguishing characteristic of cultural entrepreneurs appears to be personal involvement in the creative process.

Another major observation is that cultural entrepreneurs in many sectors are reluctant to label themselves as entrepreneurs (Werthes, Mauer, & Brettel, 2018; Haynes & Marshall, 2018) because they do not want to set the emphasis on the economic dimensions of their work at the expense of the cultural values they deliver. They frequently have to negotiate the risks associated with the maintenance of a high level of autonomy in their cultural practices (Naudin, 2017). They sometimes are 'pushed' (Oakley, 2014), 'pulled' (Bridgstock, 2013), or take the risk by the 'necessity of choice' (Banks et al., 2000) to become entrepreneurs. The uncertain and project-based work in cultural and creative industries influences the decision of cultural workers to start their entrepreneurial initiative.

Scholars describe cultural entrepreneurs as people who are breaking the rules and crossing boundaries (Spilling, 1991), overcoming obstacles (Amolo & Beharry-Ramraj, 2015), blurring the boundaries between work and personal life (Bridgstock, 2013; Werthes et al., 2018), showing passion and commitment to artistic content, persuasive, prudent and exhibiting courage, hope and faith in what they are doing (Klamer, 2011), risk-taking (Wardani et al., 2017), showing high tolerance of ambiguity, perseverance, self-reliance, autonomy, and creativity (Bhansing et al., 2018; Werthes et al., 2018). Kohn and Wewel (2018) in their recent empirical research on cultural entrepreneurs in Germany, find that they are usually younger and better educated compared to the entrepreneurs in other business sectors.

Other important assets for cultural entrepreneurs revealed in the academic literature are the significance of place and social networking (Heebels & Van Aalst, 2010; Lange, 2011; Naudin, 2017). The place is a precondition for the creation of networks of cultural workers and entrepreneurs. Coulson (2012) describes the networking as 'an essential entrepreneurial skill' for cultural and creative entrepreneurs, while Konrad (2013) adds that it is 'perhaps the most important element in the entrepreneurial behaviour'. Unlike entrepreneurs in other business sectors, cultural and creative entrepreneurs seek cooperation with others. They spontaneously build networks which could be characterised by friendship, cooperation, support, collaboration, learning opportunities (Coulson, 2012), creating an identity and gaining experiences (Heebels & Van Aalst, 2010), as well as spaces in which they prefer to combine their talent, co-create and inspire each other (De Klerk, 2015). However, networking can serve in more conventional ways as contacting cultural gatekeepers, building up a reputation, finding employees, funding, and creating market opportunities.

Cultural entrepreneurs are driven by complex motives. Their motivation, desire, and experience are determinants for starting an entrepreneurial or self-managed career (Amolo & Beharry-Ramraj, 2015). The motivation for most of the cultural entrepreneurs is making a decent living (Phillips, 2010; Coulson, 2012), building social reputation and career achievement (Chen, Chang & Lo, 2015) than solely financial success. They prefer to engage in activities, which align with their career aspirations and identities (Scott, 2012). Cultural entrepreneurs with an artistic background are triggered by intrinsic motivation as artistic fulfilment and growth, creation of beauty, the challenge of creating something new (Bridgstock, 2013), and passion for work (Bhansing et al., 2018; Gregory & Rogerson, 2018). Some cultural entrepreneurs decide to start a business because of the frustration in their sector and identified the market gap as an opportunity for innovation (Gregory & Rogerson, 2018). Cultural and creative entrepreneurs are passionate about their work and eager to achieve self-realisation (Wright, Marsh & McArdle, 2019), which may lead to unprofitable self-exploitation (Oakley, 2014; Werthes et al., 2018). They are continually trying to find a balance between artistic, financial, and self-development needs (Werthes et al., 2018). The long-standing contradiction between art and business that persists in the minds of cultural entrepreneurs explains their attitude and distinctive behaviour in the decisions they make about their cultural businesses.

3.2.2 Business models

Another research domain of exploration of cultural entrepreneurship is the business models employed in realising entrepreneurial endeavours. Cultural entrepreneurs act in a constantly changing environment, mainly because of the rapid development of new technologies, changing tastes of the audiences, and unpredictable transformations in value chains. In this environment, they stand in a unique situation with respect to risk and social trust. Risk management and trust development are identified as central features in the establishment and development of cultural businesses (Banks et al., 2000). New technologies have brought more complex artistic and cultural markets (Benghozi & Paris, 2014), in which the new ways of design, production, and distribution make available new business models and open niches for new players in the value chains.

Cultural entrepreneurs can generate new jobs, economic growth, and promote social cohesion and a sense of belonging (Wilson & Stokes, 2002). They provide new models of work and creative production, which are built on technological advances and their incorporation in people's lives. Cultural entrepreneurs are seen as more 'independent' in character (Wilson & Stokes, 2002; Walzer, 2017), driven by their own belief. The new model of work, according to Wilson and Stokes (2002), consists of four key ingredients: blurring boundaries between consumption and production and between work and non-work, combination of individualistic values with collaborative working and involvement in the wider creative community. All of these ingredients contribute to the uncertainty in cultural and creative industries, but at the same time, cultural entrepreneurs show a higher degree of introducing market novelties and product or soft innovations (Kohn & Wewel, 2018).

Benghozi and Paris (2014, p. 79) characterised the environment with 'unstable business models and different bases from one sector to another' in which cultural entrepreneurs have to continually search for new products, innovations, new business models and new ways of value creation to be successful over a long time (Warren & Fuller, 2010; Walzer, 2017). Cultural entrepreneurs appear to be highly adaptive by creating networks, clusters, and informal infrastructures in big cities. Some scholars (Banks et al., 2000; Wilson & Stokes, 2002; Haans & van Witteloostujin, 2018) point out that many cultural firms prefer to remain small or medium size (especially those in core cultural industries), concerning infrastructural risk, problems in administration and management, unwillingness to trade ownership for equity, etc. By developing networks, which are both social and professional, cultural entrepreneurs maintain strong and long-standing relations with clients, colleagues, and gatekeepers, as well as, keep the opportunities for new collaborations and cultural projects open and receive needed training and mentoring.

Other distinctive features of the employed business models by cultural entrepreneurs identified in the academic literature are the cultural value and symbolic knowledge that their projects contextualise. The risk and uncertainty of the prevalence of these intangible assets are one of the peculiarities of the cultural entrepreneurs' business models (Fontainha & Lazzaro, 2019). Therefore, intellectual property is a primary concern (Banks et al., 2000; Calvo et al., 2017), because of its economic importance in the realisation of cultural products.

The research on the business formation of cultural organisations also includes the area of non-profit organisations, especially in traditional art sectors (performing arts, visual arts, classical music). According to Preece (2011), art organisations in the non-profit sector are formed out of 'a sense of calling', transformed into an organisational mission, which has to balance artistic, managerial, and political logic (Lindqvist & Hjorth, 2015). These organisations struggle with the costs of maintaining their activities, positioning in the value chain, and the necessity of networking. The most important factors for arts organisations are developing audiences, financial resources, venues, the quality of artistic work (Preece, 2011), and supporting policy (Cheung Leung, 2013; Volintiru & Miron, 2015; Petrová, 2019).

3.2.3 Audience development

The topic of audience development concerning cultural entrepreneurship appears to be underexplored. The rapid changes in contemporary society, mainly globalisation and new information and communication technologies, have situated the audiences in the centre of cultural production, transforming them into users, co-creators, prosumers, etc. The new participatory culture and user-generated content suggest that the audience more frequently interacts and co-creates with the artist, and it is no longer a passive recipient of the cultural content. As Knudsen et al. (2014) point out, the question today is not whether the audience participates but to what extends it participates and engages.

In the new situation, cultural entrepreneurs can reach their audience directly through digital media and without using the traditional intermediaries, and interact with geographically dispersed audiences. The independent artists have become sufficient not only in the cultural production by accessing the needed technological tools, but in distribution, promotion, marketing, and audience building (Meissner, 2016; Walzer, 2017). For many cultural sectors, new technologies have allowed the creation and sharing of artworks to happen outside mainstream media establishments. For instance, Meissner (2016) explores the audience building in independent filmmaking and finds out that the internet has allowed entrepreneurs to build their audience without using sale agents, broadcasters, and distribution companies. However, the internet has not 'turned audience building upside down' (Meissner, 2016, p. 82). The new technologies have made possible the overcoming of some intermediaries, cheaper reach to the audience, but do not change the fundamental principles in audience building (Meissner, 2016). Today, cultural entrepreneurs have new means to promote themselves and their work, attract a global audience, interact directly with their audience, and turn them in advisers and partners in creating cultural products by using digital media. In that regard, audience development is a significant element in the area of cultural entrepreneurship, and further research is required for identifying the changing conditions and new modes of interactions between cultural entrepreneurs and their audiences.

3.2.4 Use of the information and communication technologies

Another topic that needs further research is the role of new information and communication technologies for cultural entrepreneurship. The rapid technological development has radically changed how cultural and creative businesses operate. On the one hand, digital technologies have a significant impact on the growth of cultural and creative industries (Ó Cinnéide & Henry, 2007) by changing the structure of value chains in cultural sectors (Benghozi & Paris, 2014), introducing new niches and giving rise to a new generation of independent entrepreneurs (Walzer, 2017). On the other hand, new technologies fundamentally transform the ways in which cultural products are created, distributed, and consumed, and increase the audience participation in these processes and user-generated content (Knudsen et al., 2014) significantly. Cultural entrepreneurs constantly absorb new technologies in their work (Ó Cinnéide & Henry, 2007) and create new possibilities, which can challenge or even disrupt the existing industry patterns (Warren & Fullen, 2010). The use of information and communication technologies turns to be viable in every aspect of cultural business, and the availability of production devices becomes a prominent way to transform artists into entrepreneurs.

Scholars have gradually started exploring different aspects of the changes caused by new technologies to the behaviour of artists and producers. For instance, Walzer (2017) investigates the independent music industries and finds out that the availability of sophisticated technological tools has allowed independent producers, artists, and musicians to develop their recording and promotion skills and offer new cooperative business models. The migration to the so-called 'bedroom studios' has changed the music industry by making independent artists capable of producing high-quality sound and generating profits without using a major label to support them (Walzer, 2017). Independent artists have more options to not only produce and distribute their artworks but to learn and upgrade their production and business skills through tools available online and communities of collaboration.

By acknowledging that creators and producers can distribute their content directly to consumers, Benghozi and Paris (2014) identify various new intermediation patterns, which alter the cultural sectors and challenge their traditional hierarchies. These new intermediations are the driver of the reorganising cultural industries by introducing new forms of entrepreneurship and new economic terms (Benghozi & Paris, 2014). For instance, traditional intermediaries as bookstores and music stores have given way to new online aggregation platforms and search engines. By opening new niches, cultural entrepreneurs test innovative business models not only in content production but also in making the content available to a larger, even global audience. The turbulent changes in the digital realm have a direct influence on cultural entrepreneurial practices, and further empirical research could give more light on different strategies of entrepreneurs in coping with the new challenges.

3.2.5 Urban development

Scholars and policymakers have recognised the importance of culture and the arts for the economic development of cities and regions. Cultural entrepreneurship could be seen as the focal point between culture and business and has a significant role for regional development and planning (Ratten & Ferreira, 2017) and the enrichment of the quality of life in cities. Hence, the importance of regional studies of cultural entrepreneurship has been enhanced by creativity-based policies for regional and urban economic development (Qian & Liu, 2018).

Ratten and Ferreira (2017) point out that the innovative potential of regions depends on their ability to boost cultural entrepreneurship. The place increases the chances for new and innovative collaborations by bringing together different ideas and knowledge (Lindkvist, 2013) and can become a creative environment that inspires new cultural businesses to be established (Gregory & Rogerson, 2018). Go et al. (2014) examine the role of cultural entrepreneurship for place branding as it offers a new course for the revitalisation of local communities and positively influences local economies. Loy (2014) argues that cultural entrepreneurs are foundational and key stakeholders in shaping place and place branding initiatives. On the one hand, cultural entrepreneurs usually start their initiatives in big cities where they can develop relationships and networks with each other and find an audience for their products. On the other hand, they can change the dynamics of the cities and bring more value to local communities, as well as to contribute to a sustainable economy and quality of life.

Policymakers have gradually started using the discourse of cultural entrepreneurship in urban regeneration initiatives, especially for industrial sites, as this is the case in the Netherlands (Metze, 2009). As Metze (2009) shows, the dominant discourse of entrepreneurship primarily concerns the economic value of the location and advocates the building of business offices and centres. However, the discourse of cultural entrepreneurship offers an alternative interpretation and aligns entrepreneurship with the cultural value that artists deliver to society. The regeneration of industrial sites by inviting artists and cultural businesses have the potential to generate new business models, which bring more investments, lower costs and more added value in the long-term. Furthermore, Phillips (2010) suggests that every city has the potential to become a creative city if it finds the proper balance between, on the one hand, the private sector and the market and, on the other, the public sector and government involvement. In this regard, cultural entrepreneurship needs to be defined by policymakers in the strategic planning of cities.

3.2.6 Public policy

The research on cultural entrepreneurship is related to the important domain of public policy. The support, which local authorities and national governments can provide, is crucial for the development of all sectors of cultural and creative industries. The recognition of their role for economic development, social cohesion, and everyday life has brought new policy measures for stimulating cultural and creative entrepreneurship around the world. The selected publications in this domain cover a wide range of countries, which shows that the topic is vital for the practice of cultural entrepreneurship.

Ó Cinnéide and Henry (2007) point as main reasons behind the governments' involvement in supporting cultural and creative industries, the central role of these sectors for everyday life, their growth because of new technologies and globalisation, their potential for exports, international partnerships and foreign investments, and their capacity to absorb new technologies to add value to their products. However, in many countries, there are different issues, which policymakers have to deal with. Haans and van Witteloostuijn (2018) show that depending on the cultural or creative sector, the growth expectations in the aspect of job creation differ, and policymakers should focus on sectors' specifics in providing funds and support to cultural entrepreneurs. The most pressing problems are the need for highly skilled workers, better access to finance, promoting cultural and creative industries to reach high export levels, and the protection of intellectual property rights (Ó Cinnéide & Henry, 2007). Furthermore, Lazzeretti and Vecco (2018) encounter the risk of receiving insufficient support from the industry policy and actions because cultural and creative industries are outside the main sectors.

Cultural entrepreneurship is also connected to new policy agendas for facilitating a knowledge-based or creative economy and the concept of the creative city. The knowledge economy and the prominence of the role of creativity for economic development have become motivators for many policymakers to produce strategies, which aim at promoting the arts as a means 'to help establish a new economic foundation for future economic growth' (Philips, 2010, p. 6). One of the major issues in the domain of public policy is the tensions and controversial relationship between cultural policies and economic development. Arts and culture have a special place in people's lives because of the spiritual, intellectual, and emotional meanings that they bring. As a meeting point, cultural entrepreneurship could contribute to economic development, but finding the balance between cultural values and economic goals is a key challenge for policymakers.

3.2.7 Clusters and incubators

Clusters and incubators in cultural and creative industries and the arts have a significant role for cultural entrepreneurs and the development of their business ideas into successful organisations. As mentioned, networking is one of the key instruments for cultural entrepreneurs to find new opportunities for work, collaborations, and partnerships. For cultural entrepreneurs, the place where they are situated has a special meaning because it provides space for social interactions, proximity to other creative individuals, and the exchange of ideas. In that regard, formulations of clusters in cultural and creative industries are beneficial for branding the city, urban regeneration of industrial areas, stimulating creativity and economic development. As Heebels and Van Aalst (2010, p. 347) point out, 'clusters facilitate an unintentional coming together of gossip, ideas, pieces of advice, and strategic information'. Clusters can be seen as not only an economic instrument for the conduct of urban policy but as authentic locations and environments which meet cultural entrepreneurs' desires and needs.

Art and creative incubators are another new organisational form used by cultural entrepreneurs. Incubators provide support for entrepreneurs, artists, and organisations to develop their business and artistic ideas into products and services. The value that incubators create is delivered in three ways: premises, knowledge, and networks (Franco et al., 2018). The different services of art and creative incubators include providing facilities, consultations and office services, training and mentoring, funding, and sponsorship. They can include not only for-profit start-ups but also non-profit organisations and individuals. In that way, they serve cultural, economic, and community development (Essig, 2018). Incubators can be seen as 'platforms' because they can be found not only at a specific place but also in the virtual space (Essig, 2014). Further research on these new organisational forms could have practical implications, as Essig (2018) points out, their added value or impact should be tracked over time. Such research will help with the creation of better services for new cultural businesses, give needed data and recommendations for policymakers for their urban strategies, and measure the impact of creative clusters and incubators for community, entrepreneurs, and economies.

3.2.8 Entrepreneurial education

Research on cultural entrepreneurship includes the domain of entrepreneurial education. The topic is recognised as an important element for the competitiveness of cultural and creative industries in the light of the economic significance of these sectors (Rae, 2004), the big percentage of micro and small businesses (Larso, Saphiranti, & Wulansari, 2012) and self-employment (Carey & Naudin, 2006; Küttim, Arvola, & Venesaar, 2011). In some countries, entrepreneurial education in these sectors is encouraged by the government, as in the case in the U.K. (Carey & Naudin, 2006).

The academic research on entrepreneurship education in cultural sectors could be categorised into two main traditions. Essig (2017) shows that the prevailing discourse in U.S. higher education adopts a narrower term' art entrepreneurship' in comparison to Europe and Australia, where the term' cultural entrepreneurship' has been conceived and developed earlier. The differences in the two approaches are around the distinction between organisational leadership in Europe and individual artistic behaviour in the U.S. In Europe, cultural entrepreneurship tends to be offered through management or business programs, as Thom (2017) confirms through an empirical study that art entrepreneurship education of fine art students is in a poor state and it is not implemented at higher education institutions in the U.K. and Germany. In contrast, in the U.S. art entrepreneurship curriculum has developed from within arts disciplines and is offered through arts and liberal arts units (Essig, 2017). The major issues are the definition of what entrepreneurship means in respect to art education (Bridgstock, 2013) and overcoming misperceptions about the value of the training on entrepreneurship among students and faculty (Gangi, 2015). In the last years, more research originates from South-East Asia, particularly Indonesia, with a focus on entrepreneurial learning for creative industries and the use of new information and communication technologies.

Regarding cultural entrepreneurship education, scholars confirm the need for combining education and experience (Küttim, Venesaar & Kolbre, 2011; Rae, 2012; Setiadi, Duparmin & Samidjo, 2018). One of the earliest empirical researches (Raffo, Lovatt, Banks & O'Connor, 2000) shows that entrepreneurial learning in cultural industries is most productive when it includes "doing" and reflecting "on doing" in the concrete sectors and developing appropriate social and cultural capital. Rae's research (2004) on creative industries offers a practical model for entrepreneurial learning, which encompasses three key domains: personal and social emergence (developing of personal and social identity as an entrepreneur), contextual learning (recognising social and industry opportunities and gaining experience), and the negotiated enterprise (understanding of enterprise identity, practices, and credibility within wider networks). Carey and Naudin (2006) point out that the role of higher education is to provide entrepreneurial spirit among students in creative industries programs by creating attitudes, presenting entrepreneurial activities in project-based work, and acknowledging the local creative industry. Universities can form a clearer idea among students about the realities of the market by close collaboration with external organisations, practitioners, and industry.

Beckman (2007) delineates two main streams concerning entrepreneurship education in the U.S.: entrepreneurship as 'new venture creation' and as 'being enterprising'. Bridgstock (2013) further builds on these presumptions by presenting a set of skills corresponding to these streams and suggests a third sense of arts entrepreneurship, which relates to employability and the need for developing skills related to career self-management. Schediwy, Loots and Bhansing (2018) empirically test Bridgstock's conceptualisation of arts entrepreneurship education among music students in the Netherlands and discover positive attitudes of students to the three approaches to entrepreneurial education. Cultural entrepreneurial learning is becoming an important topic among scholars, and new educational programs are about to emerge. A close look and evaluation of these programs are crucial for boosting cultural entrepreneurship.

4. Conclusion

This paper contributes to the body of research literature through the quantitative and qualitative analysis of publications on cultural entrepreneurship. A total of 131 English language publications were identified via Scopus, published during the period 1982-2019. Findings show that the number of publications on cultural entrepreneurship is increasing, especially since 2006; empirical publications dominate, and the geographic scope of countries is very broad. Furthermore, eight research domains emerged from the thematic analysis of the literature, namely: 'Characteristics and motivation of entrepreneurs', 'Business models', 'Audience development', 'Use of information and communication technologies', 'Urban development', 'Public policy', 'Incubators and clusters' and 'Entrepreneurial education'.

The main limitation of the paper is that only English-language publications in Scopus were included in the analysis. The authors acknowledge that there might be other relevant English-language publications not indexed in Scopus or published in languages other than English that might be included in future studies.

From a theoretical perspective, the quantitative analysis indicated that research domains such as 'Incubators and clusters', 'Audience development', and 'Use of information and communication technologies' are underresearched. In the contemporary competitive world, these domains are preconditions for the success of entrepreneurial practices in cultural and creative industries and the arts. Incubators and clusters have a direct impact on the formation of new entrepreneurial start-ups in cities and regions, which have the potential to transform these places by offering a wide variety of new and innovative cultural and creative products and services. The use of information and communication technologies in different stages of realising cultural products or services (e.g. production, aggregation, distribution, and consumption) opens new opportunities for a restructuring of value chains, giving more freedom to entrepreneurs and artists to innovate and make possible easier access to a larger audience. More research on audience creation and development is needed for a better understanding of the constantly changing tastes and behaviours of contemporary users and consumers, which will have a practical implication on improving the performance of cultural entrepreneurial start-ups and established cultural organisations.

From a managerial perspective, the cultural entrepreneur is gradually becoming a central figure in contemporary cultural processes who has the potential to fulfil the market and audience needs, fill the emerging business niches, and contribute to the revitalisation of cities and regions. Globalisation, participatory culture, and digital technologies have evoked the need for new business models and organisational forms, more interactive experiences for audiences and creative approaches in every stage of realisation of cultural products and services. Modern technologies (e.g. virtual, augmented and mixed realities, robots) can be utilised to create new cultural products/experiences by not only newly incubated start-ups, but also already established cultural institutions. New organisational forms as clusters and incubators, as well as, consistent urban policies, can have a positive impact on economic growth and social cohesion of cities and countries. Furthermore, cultural entrepreneurs experience difficulties in finding the balance between cultural and economic values, which evokes tailor-made support from nation-states.

From a policy perspective, governments need to stimulate cultural entrepreneurship to revitalise urban development and improve the quality of life of their communities. This needs to happen on various levels. Governments should encounter contemporary challenges in front of cultural organisations and provide a legal environment that stimulates private entrepreneurship and private-public partnerships in cultural industries. Additionally, education in cultural entrepreneurship will provide graduates with relevant knowledge and skills to establish competitive companies.