1. Introduction

This paper aims to present a model explaining the territorial factors of tourism destinations regarding their internationalisation. In addition, the relationships between the factors associated with this model are clarified, and the steps inherent to the various validation studies of the instrument built for this purpose are explained, namely content, construct and reliability validation. The analysis of the territory, from the perspective of its internationalisation, highlights two issues: (i) the definition of the geographical boundaries of destinations in line with the identity and culture of the regions; (ii) the economic viability of territories (Blasco, Guia & Prats, 2014b; Bohlin, Brandt & Elbe, 2016; Brouder & Ioannides, 2014). Clarifying the factors that most contribute to regional competitiveness is one of the objectives of this investigation.

This study is part of a broader investigation, which proposes a model for the internationalisation of destinations, in which the systemic perspective of tourism is strengthened due to the relationship between the dimensions of territory, product, governance model and function of Destination Management Organizations (DMOs) (Author, 2019a). The results indicate that each of the second-order constructs (dimensions) significantly reflects the latent variable it sets out from (‘internationalisation of destinations’).

The results also demonstrate that the spatial identification of destinations depends on political stability and cooperation, facilitating the network association of several administrative regions located in the same country or in different countries (Author, 2019b). From the perspective of respondents, it is one of the key strategies for the attractiveness of destinations to attract tourists and stimulate the economy. For this reason, the existing economic activity in the territory should begin to appear as a structural feature of tourism competitiveness. In other words, a territory may have a strong spatial identity and fail to attract tourists, because it is the economic dynamics inherent to tourist companies’ activity and the organisation of connections that enhances natural and cultural resources, which facilitates the arrival of tourists to destinations, as well as stimulating their motivation to move within that space. Revitalising tourism in a post-COVID 19 era involves supporting both tourist and otherwise businesses to maintain this dynamic. It is argued that policies to revitalise tourism must take this objective into account, which is crucial to strengthening the sector.

Destinations are constructed through social, cultural, political and economic relationships. For these reasons, its geographical boundaries must be formed by its attractiveness potential, measured by tourist flows and consumption patterns (Moreno- Luna, Robina-Ramírez, Sánchez & Castro-Serrano, 2021). The COVID 19 pandemic had a particularly negative impact in this area, with consequences for the impoverishment of regions. Revitalising local economic development also implies revitalising tourism, channelling public funding to projects that make the most of existing resources (Arbolino, Boffardi, De Simone, & Ioppolo, 2021). The connection of the territory's economy to cultural identity and policies that facilitate the organisation of networked destinations, fundamental conditions in the internationalisation of destinations, emerge as fundamental aspects for the recovery of tourism in the post- COVID period (Chica, Hernández & Bulchand-Gidumal, 2021).

2. Literature Review

The internationalisation of tourism destinations accompanies the economic development of regions if it contributes to the competitiveness of the territories. Increasing levels of competitiveness are a goal for many economies and territories around the world (Badulescu, Hoffman, Badulescu & Simut, 2016; Bannò, Piscitello & Varum, 2015). This movement is reflected in an increase in companies' skills in terms of knowledge of international marketing practices, information gathering and attention to business opportunities. There is a change in perspective regarding the development of regional economies, reinforcing the importance of framing them in a certain spatial context (Brouder & Ioannides, 2014). The regional economy is changing through irreversible and dynamic processes that emerge from the behaviour of economic agents (individual or organisational). It is as if the globalisation of the economy had the effect of shifting the importance from the national level to the regional and local level (Bohlin, Brandt & Elbe, 2016; Clavé & Wilson, 2017). In other words, the internationalisation of destinations is achieved by strengthening regional competitiveness. In this perspective, regional economic growth depends on a framework of development policies, which should boost the competitive advantage of companies and destinations (Booyens, 2016). In this context, regional economic development should aim to

increase the competitiveness of destinations by increasing business and work opportunities and, above all, by promoting skills that are favourable to the action of internationalisation (De Noni, Orsi & Zanderighi, 2014).

The question of the spatial definition of destinations has concerned the scientific community, with repercussions on territorial planning and organisation (Author, 2020; Nilsson, Eskilsson, & Ek, 2010). Including resources and geographical boundaries in this context has been one of the most widely used strategies. However, the identification of destinations always ends up following the administrative division of the territory, because the responsibilities for regions’ development are so defined (Szytniewski, Spierings, & van der Velde, 2017; Timothy, Saarine, & Viken, 2016). It is usually political entities, or others recognised by them, that have this role. Some authors question this premise because they do not recognise advantages for tourism competitiveness, arguing that tourists move according to the tourist experience (Author, 2019b). Tourists are also attracted to destinations whose support structures facilitate their travel, guarantee their safety and allow access to different resources (Abraham, Bremser, Carreno, Crowley-Cyr & Moreno, 2021). In this context, the greater the dynamics of economic activity in the territories, the greater their ability to transform resources into innovative, attractive and diversified tourist products (Makkonen & Rohde, 2016; Makkonen & Weidenfeld, 2016; Makkonen & Williams, 2016; Vodeb, & Rudež, 2016). The territory has institutions, processes, services and businesses that reflect the culture and identity of the region and highlight the integrated system of relations between stakeholders and policies (Bannò, Piscitello & Varum, 2015; Bernabé & Hernandez, 2016; Bohlin, Brandt & Elbe, 2016).

To strengthen this economic dynamic, policies must lead to a strategy of enhancing the economy and business, leveraged in the identity of destinations (Araújo, 2013; Bornhorst, Ritchie, & Sheehan, 2010; Della-Corte, 2013; Pillmayer & Scherle, 2014; Spyriadis, Fletcher & Fyall, 2013). This interrelation affects destinations’ capacity to attract and be competitive, as long as the strategy followed is based on knowledge, innovation and marketing (Booyens, 2016; Booyens & Rogerson, 2015; Booyens & Rogerson, 2016; Makkonen & Rohde, 2016; Sertakova, Koptseva, Kolesnik, et al., 2016; Weidenfeld, 2013).

The internationalisation of destinations is aligned with a concept of territorial economic development that values quality, innovation, identity and differentiation (Getz & Page, 2016; Sakharchuk, Kharitonova, Krivosheeva & Ilkevich, 2013; Sertakova et al., 2016; Vermeulen, 2015; Vodeb & Rudež, 2016; Więckowski & Cerić, 2016). Being competitive, in this context, involves being innovative and being able to place on the international markets what is distinctive when the products are imbued with the local cultural identity. Here, the internationalisation of destinations is triggered and consolidated, not only by the competitiveness of the price but mainly by the region’s organisational and relational capacity, which guarantees stakeholders’ active participation in this process. These are responsible for valuing and promoting endogenous, specific and non-transferable resources. Regions no longer compete only with their neighbours at the national level. Destinations compete with others that are often located far from their borders. The market is global. For this reason, local economic and social vitality, that is, territorial competitiveness, faces the challenge of selling products in this international market, taking them to the consumer's door. Hence the importance of marketing; it is not enough to produce; it is not enough to be different and have quality; it is essential to make these products attractive and easily accessible to customers worldwide. In these conditions, destinations increase their internationalisation capacity because they are recognised as having attributes inherent to differentiation, quality and safety. For these reasons, economic activity appears as a structuring factor in crisis management, namely triggered by the current pandemic (Matiza, 2020), inherent to the spatial identification of destinations, along with resources and geographical limits.

3. Method

3.1 Sample

The sample is formed of 147 organisations, within a target population of 470 public and private Portuguese non-profit organisations with responsibilities in different areas of tourism, product competitiveness and local/regional development, the majority being Municipal Councils (69.4%). These organisations are responsible for defining priorities and actions to develop the territory and its products or managing the implementation of public policies concerning tourism as a whole. Seven NUTII locations were considered, the scope of influence being from local (70.7%) to international (2.7%)

Most respondents were aged from 35 to 49 years old (63.3%), and there were more females (61.2%) than males (42.5%). The majority are administrative employees (68.7%) and aged 35 to 49 (63.3%). Most of them have higher education qualifications, with a degree (45.6%), master (24.5%) or postgraduate studies (15.6%) (see Table 1).

Table 11 Sample characterization: Participants and DMO [N = 147]

| n* | % | ||

| Sex | Female | 90 | 61.2 |

| Male | 54 | 36.7 | |

| Age (years) | < 35 < 49 | 93 | 63.3 |

| < 50 < 64 | 31 | 21.1 | |

| < 25 < 34 | 19 | 12.9 | |

| < 18 < 24 | 1 | 0.7 | |

| Academic qualifications | Secondary Education (12th year) | 8 | 5.4 |

| Bachelor | 7 | 4.8 | |

| Degree | 67 | 45.6 | |

| Postgraduate studies | 23 | 15.6 | |

| Master | 36 | 24.5 | |

| PhD | 4 | 2.7 | |

| Professional category | Admin. worker | 101 | 68.7 |

| Director | 14 | 9.5 | |

| Assessor | 7 | 4.8 | |

| President | 6 | 4.1 | |

| Other | 17 | 11.6 | |

| Councillor | 5 | 3.4 | |

| Head of Division | 5 | 3.4 | |

| Head of Unit | 3 | 2.0 | |

| Executive | 1 | 0.7 | |

| Office clerk | 1 | 0.7 | |

| Graduate staff | 1 | 0.7 | |

| Assistant | 1 | 0.7 | |

| Organisation | Municipal Council | 102 | 69.4 |

| Development and / or promotion association | 12 | 8.2 | |

| Public entity for development and territorial planning | 11 | 7.5 | |

| Regional tourism entity | 7 | 4.8 | |

| Representative entity of the municipal association | 6 | 4.1 | |

| Sectorial Association | 5 | 3.4 | |

| Tourist Promotion Agency | 2 | 1.4 | |

| Organization Location NUTII) | Centre | 47 | 32.0 |

| North | 41 | 27.9 | |

| Lisbon Metropolitan Area | 17 | 11.6 | |

| Alentejo | 15 | 10.2 | |

| Algarve | 10 | 6.8 | |

| Autonomous Region of Azores | 8 | 5.4 | |

| Autonomous Region of Madeira | 7 | 4.8 | |

| Scope of influence | Local | 104 | 70.7 |

| Regional | 27 | 18.4 | |

| National | 10 | 6.8 | |

| International | 4 | 2.7 |

* Missing values = 2, corresponding to 1.4% of the sample

3.2 Materials

A survey was carried out using the self-administered Questionnaire on Internationalisation of Tourism Destinations (QITD) - which aims to make up for the lack of instruments assessing the internationalisation of destinations. The QITD intends to assess the territorial dimension of tourist destinations. Based on state of the art, a set of items were joined concerning stakeholders, attributes, borders, and resources related to territory. The QITD was formed of 21 items evaluated through a Likert Scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), comprising stakeholders (5 items), attributes (6 items), borders (3 items), and resources (7 items) of the territorial dimension of tourism destinations, aiming to fill the lack of instruments for evaluating the internationalisation of destinations (see Table 2 and Appendix 1).

Table 2 Factors and items proposed for the Territory (QITD)

3.3 Procedures

An online version of the questionnaire was sent by e-mail to all Portuguese municipalities, with a reminder one month later to those that had not yet responded, emphasising the importance of their participation. The questionnaire was to be filled in by those with responsibilities in tourism. Information on the study's objectives, completion instructions, the voluntary and anonymous nature of participation, and the guarantee of individual data confidentiality were included, meeting ethical requirements. Each item in the questionnaire was rated on a seven-point Likert scale (from 1 = Not at all important; to 7 = Extremely important, and N/S = I do not know).

3.4 Data analysis

The analyses were completed using IBM SPSS and AMOS software. Frequencies were examined in order to eliminate items without variation, and outliers were analysed according to Mahalanobis squared distance (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). The normality of the variables was assessed by the coefficients of skewness (Sk) and kurtosis (Ku), and no variable presented scores violating normal distribution (|Sk|<2; |Ku|< 3). The central tendency measures indicate that the mean scores are close to the median and mode in all items. Dispersion measures reveal that the tendency to respond to items is distributed across almost all options on the scale.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed using principal component analysis (PCA), statistical techniques are applied to a set of items in which the researcher is interested in discovering which items in the set form coherent subsets relatively independent of each other, corresponding to the scale’s factors or dimensions. This technique aims to produce linear combinations of original variables, each linear combination being a factor. With this technique, we aim to produce linear combinations of original variables (the scale items), each linear combination being a factor. (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013).

The PCA assumptions were tested through the sample size (minimum ratio of 5 subjects per item: Gorsuch, 1983), normality and linearity of the variables, factorability of R, and sample adequacy (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). Since we intend to retain independent factors, we have chosen VARIMAX rotation with Kaiser’s normalisation.

Confirmatory factorial analysis (CFA) was performed with AMOS (Arbuckle, 2013), a multivariate technique intended to confirm the factor structure previously found in the PCA. The maximum likelihood estimation was adopted (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 2004). We adopted a psychometric perspective, inferring latent variables (the scale factors) from multiple observed measures (the scale items). The model goodness of fit was analysed by NFI (normed fit index; good fit > .80; Schumacker & Lomax, 2016), SRMR(standardized root mean square residual; appropriate fit < .08; Brown, 2015),TLI (Tucker- Lewis index; appropriate fit > .90; Brown, 2015), comparative fit index (good fit > .90; Bentler, 1990), RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation; good fit < .05; Kline, 2011; Schumacker & Lomax, 2012), and χ2/df (p > .05; Bentler, 1990; Schumacker & Lomax,2012). The model fit was improved by modification indices (Bollen, 1989), considering releasing parameters with MI > 90.

Reliability was calculated by Cronbach’s alpha (Nunnally, 1978), considering acceptable an α > .70 (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, 2009). The composite reliability and average variance extracted (AVE) for each factor were evaluated as described in Fornell and Larcker (1981).

4. Results

4.1 Exploratory factor analysis

Table 2 presents the communalities, eigenvalues, and explains variance for the rotated component matrix of the PCA to carry out the exploratory factor analysis, used as a first step in the factor analysis of the items of this scale. Previously, the requirements for reliable interpretation of PCA were assured: ratio of 12.25 subjects/item, correlation matrix differs from the identity (Bartlett’s test X2(66) = 1003.59, p<.001) and anti-image

(matrix scores between .890 and .605, highest score outside the diagonal of -.488), and the sampling was adequate (KMO = .843).

The construct validity of the ‘Territory’ scale revealed three factors (factorial structure composed of three factors, each of one representing a cluster of items), with a total explained variance of 72.42% and good reliability (see Table 3). Factor 1 was called ‘Resources’, grouping five items related to attractions, infrastructure and connections. On the one hand, the diversity of attractions, combined with good connections to and within destinations, contributes to attractiveness. On the other, tourist infrastructure facilitates companies’ action and tourist flows, reflected in the attractiveness of territories.

Factor 2 - ‘Economic Activity’ - is composed of five items referring to economic viability, the existence of business opportunities, financial conditions, and access to raw materials to support business activity associated with quality of life in the territory. Factor 3 - ‘Limits’ - reflects the identity of the space: administrative, geographical and cultural boundaries, reinforcing the link between the administrative division of the territory and its geographical and cultural characteristics. According to the Territory Scale, the physical configuration of destinations should include resources, economic activity, and geographical limits, combining economy with territories’ identity, making them spatially attractive.

Table 3 PCA and reliability (α) of the Territory Scale: Factor loadings, communalities (h 2 ), eigenvalues, and Explained variance (%)

| Scale items. The following is a list of statements regarding the mapping of tourism destinations. In view of the spatial identification of destinations, evaluate the importance of defining the area of the destination through the following aspects (from 1 = 1 = Not at all important; to 7 = Extremely important): | F1 Resources | F2 Economic activity | F3 Limits | h2 |

| Tourist infrastructure in the territory. | .838 | .324 | .034 | .809 |

| Tourist companies in the territory. | .833 | .182 | .088 | .735 |

| Transport network within the territory. | .800 | .246 | .104 | .712 |

| Natural or cultural resources of the territory. | .739 | .114 | .007 | .559 |

| Transport network to the territory. | .734 | .295 | .006 | .626 |

| Suppliers to support companies' activities. | .179 | .898 | -.028 | .838 |

| Budget allocated to territorial development. | .265 | .866 | -.010 | .820 |

| Business opportunities in the territory. | .252 | .802 | .076 | .712 |

| Financial resources in the territory. | .348 | .754 | .093 | .698 |

| Geographical boundaries. | .022 | -.096 | .873 | .772 |

| Administrative limits. | -.013 | .253 | .825 | .745 |

| Cultural limits. | .135 | -.032 | .802 | .663 |

| Eigenvalues | 5.12 | 2.07 | 1.51 | |

| Explained variance (%) | 28.57 | 26.16 | 17.69 | |

| α | .883 | .893 | .786 |

4.2 Confirmatory factor analysis

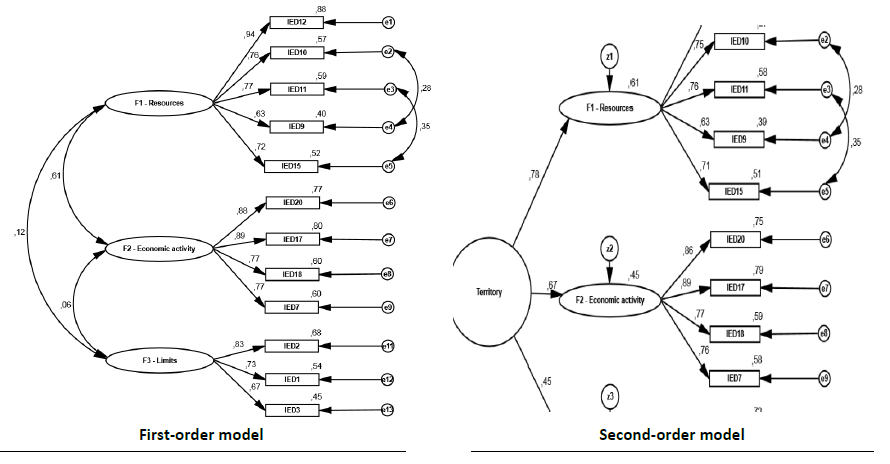

CFA was initially performed conceiving the Territory construct as a first-order construct with three inter-related dimensions.

Table 4 shows the fit statistics of this first-order model for the Territory Scale. This model showed a good fit considering NFI, CFI, TLI and SRMR, although a poor fit for the χ2/df and RMSEA (Model 1). Error terms were correlated in the ‘Resources’ factor since MI was higher than 90. This correlation indicates non- random measurement errors, which may result from some semantic redundancy in the factor’s items, items whose content is implicit in other issues, as well as the sequential positioning in the measure or the specific characteristics of the participants (Aish & Jöreskog, 1990). Content analysis of these items showed some redundancy in the items of 'transport network within the territory' and 'transport network to the territory', and the item of 'natural or cultural resources of the territory' seems to imply 'tourist companies in the territory'. After these correlations (see Figure 1) on Model 2, a good fit was obtained in the CFA (see Table 5, First-order Model 2; standardised estimates ranging from .63 to .94). Factors 1 and

2 were highly correlated (r = .61), while the correlations between F1 and F3, and F2 and F3, were insignificant (r = .12 and .06, respectively).

Table 4 Fit indices for the first and second-order models of the Territory Scale [N = 147]

| Model | NFI | SRMR | TLI | CFI | χ2/df | RMSEA | RMSEA (90% CI) |

| First- order 1 | .898 | .066 | .927 | .944 | 2.07* (df= 51) | .086 | .063-.109* |

| First- order 2 | .922 | .062 | .956 | .967 | 1.64* (df= 49) | .067 | .039-.092* |

| Second- order 1 | .886 | .102 | .916 | .933 | 2.23* (df = 531) | .092 | .070-.114* |

| Second- order 2 | .909 | .101 | .943 | .9567 | 1.85* (df = 51) | .076 | .051-.100* |

* p< .001

Figure 1 CFA representation of the first and second-order Model 2 of the Territory Scale: standardised estimates, shared variance, and error terms correlations for F1

Considering the theoretical and empirical evidence suggesting that Territory can be conceived as a latent construct, designed to measure the territorial factors that contribute to tourism destinations' internationalisation, a second-order factorial model was tested (see Figure 1). Standardized regression weights were suitable for all factors, ranging from .45 to .78, standardised estimates varied from .63 to .93, showing a consistent factorial model for the Territory Scale. Composite reliability showed good scores for the three factors (CR>.70; Hair et al., 2009), the same occurring for the average variance extracted (AVE>.50; Bagozzi & Yi, 1988), since the explained variance is greater than the residual variance, indicating convergent validity.

The shared variance (R2) among factors indicated discriminant validity, given that the AVE in each factor exceeded the shared variance between each factor (Fornell & Lacker, 1981), namely R2 F1,F2 = .372, R2 F1,F3 = .014, and R2 F2,F3 = .004. Factor 1 showed the highest mean score (M = 6.18), although the three factors presented averages higher than 5 on the Likert scale.

Table 5 Composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), descriptive (min, max, M, SD, Sk, Ku), and shared variance (R2) among factors for the Territory Scale

| R 2 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | AVE | α | min | max | M | SD | Sk | Ku | F1 | F2 | F3 | |

| Global scale ( α = .83) | - | - | .830 | 3.50 | 7.00 | 5.49 | 0.80 | -.21 | -.59 | - | - | - |

| F1- Resources | .876 | .590 | .883 | 3.40 | 7.00 | 6.18 | 0.84 | -.54 | -.21 | - | .372* | .014 |

| F2 - Economic activity | .899 | .690 | .893 | 1.00 | 7.00 | 5.37 | 1.22 | -1.0 | .53 | - | .004 | |

| F3 - Limits | .789 | .557 | .786 | 1.00 | 7.00 | 4.50 | 1.44 | -.26 | -.67 | - | ||

* p< .001

5. Discussion

The results indicate a strong association between the internationalization of destinations and the territory dimension. As for the factors that explain this dimension in the model of destinations’ internationalization are ‘resources’ and ‘economic activity’, which have the greatest influence in this process.

The ‘resources’ and ‘economic activity’ factors reveal good associations with the ‘territory’ dimension; the same is not true of the ‘limits’ factor. There is a high magnitude correlation between ‘resources’ and ‘economic activity’, low between ‘resources’ and ‘limits’ and almost zero between ‘economic activity and ‘limits’. These results seem to contradict the idea present in the literature, and so often disseminated, to the point of almost being part of common sense that mapping destinations according to the territory’s geographical and cultural characteristics contributes positively to identifying its endogenous potential and consequent internationalization. This study seeks to question this 'belief' or the common sense part that may be contained in this idea by showing that a territory can have a strong, well-known identity, concerning the harmony and richness of its natural and cultural resources, without automatically having tourism or tourists.

The proportions of explained variance and the correlation of errors associated with the variables presented in the model estimated in the CFA may help to interpret this apparent paradox. Let us see each of the factors and the items that these most imply in more detail by interpreting the structural model presented in Figures 1 and 2.

5.1 Resources

CFA confirms the high factor saturations found in the EFA between factor 1 'resources' and its items, namely: 'tourist infrastructure in the territory', 'tourist companies in the territory', 'transport within the territory', 'natural resources and cultural aspects of the territory' and 'transport to the territory'. This result highlights the importance of preconditions in the territories that make them competitive, facilitating their internationalization (Bohlin et al., 2016; Brouder & Ioannides, 2014). It reinforces the theoretical conviction that destinations need to have companies that transform endogenous resources into tourist products to become international. It is important to point out the question of connections to and within the destination. The apparent semantic redundancy observed between the two items referring to transport, highlighted by the CFA, infers that the issue of resources, in this scope, is generally due to the existence of transport, whether or not used for tourism purposes. It can also imply that transport to the destination and transport within the destination are two issues that do not exist without each other, that is, it is equally important to bring tourists to the destination just as it is essential to take tourists to the different attractions there. Looking at this problem in this way, it is not so much a similarity of content between two variables, but rather a condition of interdependence between these two types of transport, where one without the other is meaningless when the intention is to internationalize the destination (Makkonen & Weidenfeld, 2016; Pillmayer & Scherle, 2014; Scuttari et al., 2016;Weidenfeld, 2013).

The results found for factor 1 ‘resources’ make it possible to clarify the variables that reflect it. The ‘existence of tourist infrastructures’, ‘tourist businesses with endogenous products’ and ‘transport to and within the destination’ can be considered the essential aspects in delimiting the destination area. That is, more than having natural, cultural or other resources, it is important to have a business activity in the territory that is capable of transforming natural and cultural resources into tourist products, as well as taking tourists to destinations and making them reach different attractions. It is also essential to have people who trigger and maintain this dynamic, have tourist infrastructure to support companies’ actions, and focus their activity on developing products that differentiate destinations.

The new context of tourism requires that tourism products evolve towards the tourist experience, created from activating cultural and natural resources in a given region (Bernabé & Hernández, 2016). The tourist experience arises from the alliances between the offer, underlying a political strategy that promotes the incorporation of all dimensions of cultural and natural heritage. In other words, transforming this local wealth into competitive tourist resources. In this context, emphasis is placed on a product management process that places tourists at the center of the initial design phase and markets at the final stage of this chain (Blasco et al., 2014b; Bohlin et al., 2016). For Booyens and Rogerson (2016), it is still necessary to combine resources, tangible and intangible, such as knowledge, technology, experience and other personal and professional skills, to promote innovation. The offer of the tourist experience is based on a form of creative tourism that places innovation at the centre of product development. Only in this way can it respond to demand motivations. This supply model requires increased collaboration between different stakeholders from different sectors of activity, leading to a shared strategy in product definition (Booyens & Rogerson, 2015).

5.2 Economic activity

Factor 2 (‘economic activity’) links ‘suppliers of support to business activity’, ‘budget allocated to territory development’, ‘business opportunities in territory’ and ‘financial resources in territory’. The economic perspective stands out, as long as it contributes to territories’ competitiveness. Also visible is the effect that economic and political decisions have on regions’ dynamics and how this contributes to destinations' internationalisation (Bannò et al., 2015). In other words, what constitutes a comparative advantage is the ability of each region to create an environment conducive to business activity (Sakharchuk et al., 2013; Vermeulen, 2016). The association of factor 2 with ‘territory’ reinforces the idea of an economy in the territory with the ability to attract business, financing and suppliers that support and stimulate business activity. This is not unrelated to the need for public investment as a vector for development and economic diversification (Bernabé & Hernández, 2016).

Local economic and innovation policies can be the engine, or the obstacle, of contemporary regional competitive capacity because they create the legal, regulatory and financial conditions at the territorial level that stimulate innovation, knowledge and creativity (Booyens, 2016). These arguments are supported by the results found for this factor (‘economic activity’), when paying attention to the semantic content of its items. Companies’ dynamics depend on the existence of financial resources in the territory, a budget that allows it to develop and suppliers that support its activity, essential conditions for the emergence of business opportunities.

Innovation is fundamental for competitiveness in the context of new economies driven by creativity, knowledge and technological development (Booyens, 2016; Sarasa, 2015). In the internationalization of destinations, innovation must be considered at different levels. At the organizational level, through the action of companies in the innovation of products, processes and fixation of qualified human resources; at the regional level, promoting new relational and collaboration configurations between the various stakeholders that encourage networking and collaborative marketing; at the international level, the approximation of economics to politics transforms tourism into a central competence of territories, when it creates regional systems of innovation aimed at companies, local networks and the tourism system (Booyens, 2016; Booyens & Rogerson, 2015; De Noni et al., 2014; Makkonen & Rhode, 2016; Rovira, 2016). Innovation in tourist destinations must be considered a part of the economic structure, whose relationships between production, human capital, political institutions, educational entities and markets can generate processes of change and learning, enhancing their competitiveness (Weidenfeld, 2013).

5.3 Limits

Factor 3 ‘limits’ reveals some unique data. First, the variable that contributed most to explaining this construct is 'geographical limits', while the one that least reflects the latent variable is 'cultural limits'. ‘Administrative limits’ also contributed to explaining the ‘limits’ factor, which reveals the importance of political boundaries in the spatial construction of destinations and reinforces the relevance of public action in territories. These three variables behave independently, ensuring that each measures different aspects of the destination's spatial identity. However, this factor is not associated with the others because the correlation indices, both with factor 1 ('resources') and with factor 2 ('economic activity'), are not very significant (Figure 2). It should be noted that economic activity can occur alongside or on the margins of the territory’s spatial identity, without this altering the intended economic development path, which justifies the absence of inter-correlation between factor 2 ('economic activity') and factor 3 ('limits'). In addition, the 'territory' dimension is not significantly reflected in this factor ('limits'). This result suggests that the spatial limits of destinations should be treated as an autonomous issue.

However, suppose a first reading of the previous results may lead to the somewhat contradictory idea, in view of everything that has been explained so far, that destinations’ spatial identification, according to their cultural, geographical and administrative limits, is not important for their internationalization. In that case, a more in-depth reflection can clarify this apparent conflict. In fact, it is the systemic perspective that is mirrored here. The problem is not centred on statistical demonstration of the relevance of limits as a factor, but on understanding what its role is in this system, how it is reflected in the destination’s internal image, how it is projected to the outside and how territorial identity is intrinsic to the strategies and means defined to map the destination (Nilsson et al., 2010; Więckowski & Cerić, 2016).

Regions play a very important role in the economic development of countries (Bohlin et al., 2016). It is also at the regional level that, most of the time, we find tourist destinations. It has already been found that territories have a cultural and natural identity that does not, for the most part, coincide with their administrative borders. So, one of the problems facing the internationalization of destinations is the definition of their limits. To overcome this limitation, the tourist area can be organized according to the attractions and tourist flows in a given geographic region (Blasco et al., 2014b). These authors argue that destinations are built through social, cultural, political and economic relations so that their geographic space must be thought of in terms of the potential for attractiveness, reflected in the consumption patterns of tourists. A rich and diverse base of natural and built attractions, with good connections to major markets, contributes to the attractiveness of destinations (Brouder & Ioannides, 2014). For these reasons, the area of destinations should be structured based on the endogenous resources existing in a given territory, combined with the analysis of tourist flows in that geographic space.

6. Conclusion

The data suggest that the mapping of destinations, aiming for their internationalization, depends more on the territory’s economic activity and its resources than on its political, physical or cultural limits. This aspect highlights the importance of an economic structure to increase the capacity to attract tourists. This economic dynamic also endows territories with resources and skills to manage the various crises they face. And political options must take this into account when defining the territory’s administrative, geographical and cultural boundaries. For this reason, spatial identity (‘geographic, cultural and administrative boundaries’) may not be a factor in the ‘territory’ dimension, but it is argued that it is a prerequisite and transversal to the system when the aim is to internationalize the destination.

In view of these results, destinations’ spatial identification can be considered to result from: (i) the overlapping of distorted maps, in which each one represents each of the factors shown here: 'resources' (attractions and connections),'economic activity' (level of economic development) and 'limits of the destination'(natural, cultural and administrative attributes); (ii) or the issue of destination limits should be treated independently because the items that make up this factor reflect it robustly (Figure 1). This last explanation seems to make the most sense, given the results found, leading to the possibility of deepening this theme in future investigations and studying the mapping of destinations.

In fact, the exact definition of the destination area may not be very important. This may not even be the starting point of the project to internationalize a destination. Having resources and economic activity that transform them into innovative and differentiated products and stimulate the territory’s competitiveness seems to be the central issue that contributes most to destinations' internationalisation.

In short, territorial resources that support regions’ economic dynamics, connections that allow tourists to reach their destinations, as well as facilitating their movement within the destination, and companies that transform regions’ endogenous resources into tourist products, appear to be the conditions contributing to the internationalization of destinations.

This network relation forms the basis of tourism in times of crisis, such as the present. In this context, political structures must ensure the financial resources to support economic activity, creating the necessary infrastructure for that activity to take place and develop. It should be noted that this infrastructure includes transport, a key factor in attracting and allowing the movement of tourists. They must also be attentive to business opportunities, stimulating local economies. Therefore, these structures must look to destinations beyond their administrative, geographical and cultural boundaries. This implies networks and partnerships between destinations, stimulating business activity, attracting tourist flows and differentiating attractions. This networked relationship constitutes the foundations of tourism in times of crisis, such as the one we are currently experiencing.

Acknowledgements

This work is is funded by national funds through FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under project reference no. UID/B/04470/2020

We are grateful for the participation of Portuguese public decision-makers at the local level, who contributed with their experience and knowledge to the present research.