1. Introduction

Gastronomy plays a fundamental role in tourism today, as evidenced by the initiatives of tourist destinations in terms of offers that bring visitors closer to the culture of the place through food, the professionalisation of the sector, and the promotion of government plans for Gastronomic Tourism, as in the case of Spain (Europa Press, 2022). In this sense, the restaurant industry is a sector imminently linked to culture, so the rest of this lies in efforts to understand the customer, and this involves getting to know the customer's "mental software" in depth, in what we know as culture.

In this sense, although interest in the effects of cultural traits on human behaviour has increased (Jung et al., 2020), cross-cultural research on the restaurant dining experience is an underdeveloped topic so far (Seric, 2018).

Research adopting cultural frameworks such as Hofstede's (2010) associating the cultural characteristics of nations with those of customers according to their nationality is rare (Zhang et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2016). Much less frequent is research that has examined the effect of cultural values measured individually and not ecologically in the restaurant setting (Seo et al., 2018). Individual measurement of individuals' cultural values is appropriate when the unit of analysis is the individual, and the aim is to examine how their culture affects their behaviour (Yoo & Shin, 2017). Of the cultural dimensions belonging to Hofstede's (2010) cultural framework that has been analysed from an individual perspective in the scientific literature in restaurants, the following are noteworthy: individualism vs collectivism (Lin & Mattila, 2006), power distance (Kim et al., 2014) and uncertainty avoidance (Seo et al., 2018).

The literature has shown the moderating role of individual cultural values on green consumer behaviour, e.g., the more individualistic a consumer is, the more likely they are to develop good practices (Lu et al., 2015). Similarly, the moderating effect of long-term orientation in building loyalty to the restaurant has been studied (Park et al., 2013), and also in other domains such as higher education (Abubakar & Mokhtar, 2015) or banking (Abubakar et al., 2013). Similarly, individual cultural values have a clear determinant role (cause or antecedent), empirically demonstrated in areas such as education, in an attempt to understand how it affects the likelihood of bullying or being a victim of bullying (Georgiu et al., 2018), and also in consumer behaviour (Czarnecka et al., 2020).

This dichotomy has been the subject of study for researchers such as Alea et al. (2021), who recently focused on comparing the mediating and moderating role of individual cultural values to examine ethnic differences in individual's autobiographical memory, concluding that the role of culture is moderating rather than mediating.

Despite the importance of brand equity in the achievement of loyalty by companies, there are still many unresolved questions about the formation of brand equity. In the field of restaurants, research focuses on examining determinants of brand equity that have to do with stimuli related to service, food, atmosphere, or authenticity (Rodríguez-López et al., 2020), but does not address other subjective determinants intrinsic to the subject, such as personality or culture.

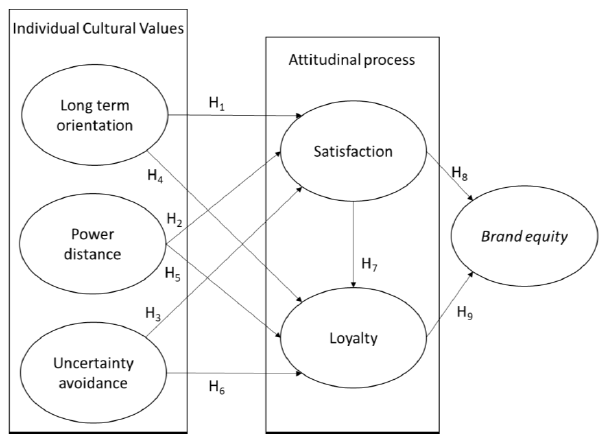

Therefore, this research aims to analyse the antecedent role of individual cultural values, time orientation, power distance and uncertainty avoidance on the attitudinal process towards the restaurant brand and to understand the process of brand equity formation from this.

2. Literature review

2.1. The role of individual cultural values in the literature

Culture, defined as all that is learned from others and transmitted, giving rise to traditions that are repeated in successive generations (Whiten, 2021), is a latent norm that conditions behaviour (Stathopoulou & Balanis, 2019).

Various cultural theoretical frameworks, all based on different dimensions that define societies, have been proposed to explain consumer behaviour (Hofstede et al., 2010; Sharma, 2010). Hofstede's (1999) cultural framework is one of the most widely used in the scientific literature. His research originated with an initial collection of 116,000 questionnaires from IBM employees in 40 countries (Hofstede, 1980). From this first contribution, he validated a model of four cultural dimensions: power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism vs collectivism and masculinity vs femininity. A second contribution led to the development of a fifth dimension called long-term vs short-term orientation (Hofstede & Bond, 1988), a dimension that captures a set of values related to persistence, thrift, responsibility, self-respect, and family and social conservatism as opposed to opposing values. The most widely used dimensions have been individualism vs collectivism (Oh et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2014) and uncertainty avoidance (Kim et al., 2016; Oh et al., 2019). But as Park et al. (2013) argue, it is necessary to conduct research that analyses other cultural dimensions such as long-term orientation for its potential effect on building customer loyalty.

On the one hand, there is a general consensus in the literature about the moderating role of culture on behaviour. Thus, Diallo et al. (2021) recently compared behaviours of Tunisian and French restaurant customers and argued that cultural value orientation over time moderates the relationships between CSR actions, the functional value of a luxury brand, the social value of a luxury brand, and the symbolic value of a luxury brand, with the willingness to pay more. They concluded that time orientation only moderates the effect of a luxury brand's functional and social value on willingness to pay more.

On the other hand, the mediating role of individual cultural values is also well known. In the field of communication, Mortenson (2002), on the basis that collectivist values prioritise relationships with others, postulated that collectivism should be a strong predictor of how people value communication. Long-term orientation, which from a conceptual point of view means the breadth of the time perspective (Saether et al., 2021), has been studied in the corporate domain with a clear mediating role. Ruiz-Molina & Gil-Saura (2012), confirmed the mediating effect of long-term orientation between trust and commitment. Authors such as Chantsaldulan and Byungryul (2013) sought to examine how a company's personnel-based loyalty, affected by economic, strategic and behavioural relational values, affects the cultural value of long-term orientation. This study was specifically applied to dairy farm owners, and the authors concluded that firm-based loyalty influences PLO to a greater extent than personnel-based loyalty.

Authors such as Saether et al. (2021), have examined the determinant role of time orientation on aspects such as green strategy and innovation in the business sector, arguing that firms with a long-term focus are more creative and innovative and have a higher tolerance for failure.

Recently, other authors such as Han et al. (2021) have proposed a mediating role of cultural values, specifically in the formation of brand loyalty, building on the work of Palumbo and Herbig (2000), who did not empirically demonstrate the relationship between culture and brand loyalty, but presented an in-depth test on the influence of culture, the geographical reach of brands, and Hofstede's dimensions, on the construction of strong brands, stating that cultures with high power distance and collectivism generally show a higher degree of brand loyalty. This position is based on the belief that consumers' attitudes toward brands shape their cultural values through cues such as brand prestige and identification (Han et al., 2021).

Derived from these reflections, this research proposes the determinant role of the dimensions of long-term orientation, power distance and uncertainty avoidance directly on customer loyalty and satisfaction towards a restaurant and indirectly on brand equity.

2.2. The formation of brand equity and restaurant loyalty based on long-term orientation, power distance and uncertainty.

Han et al. (2021) proposed that individual cultural values affect the generation of brand loyalty in restaurants, with a clear mediating role between this and other antecedent processes. However, they opened for debate on the appropriateness of the position within the model sequence. Thus, they first proposed that individual cultural values are affected by cognitive and social processes towards the brand. Secondly, they proposed that individual cultural values mediate between the cognitive and the social process, and finally, that individual cultural values mediate are affected directly by the social process and indirectly by the cognitive process. However, we understand that in the service sector, such as the restaurant industry, the attitudinal component must be a logical antecedent to the formation of brand capital, which can be influenced by individual cultural values.

The general hypothesis is that individual cultural values (long-term orientation, power distance and uncertainty avoidance) have an impact on the customer's attitudinal process towards the brand. Specifically, the following hypotheses are put forward.

Alcántara-Pilar et al. (2018) found that the effect of a user's attitude towards a website on their satisfaction was more pronounced in short-term oriented users because they seek quick results, which satisfies them quickly. On the other hand, past and present events are important for short-term oriented cultures, while for long-term oriented cultures, the most important life events have not yet occurred (Cassidy & Pabel, 2019). Therefore, it can be expected that the time orientation of the subject influences the customer's satisfaction with the restaurant.

Long-term-oriented cultures adapt easily to change, are persevering and tend to save and invest, while short-term-oriented cultures prefer to maintain traditions (Hofstede, 2011). This cultural dimension is related to tourists' high or low reliance on information sources (Cassidy & Pabel, 2019), or to a higher likelihood of making international trips in the case of long-term oriented tourists as these trips require more effort in planning (Zhang et al., 2017).

H1: there is a positive and direct effect of long-term orientation on satisfaction.

H2: there is a positive and direct effect of power distance on satisfaction.

H3: there is a positive and direct effect of uncertainty avoidance on satisfaction.

Some studies have addressed the effect of power distance on the assessment of service quality, or the formation of expectations, concluding that customers from high power distance cultures have lower expectations than customers from low power distance cultures and are more tolerant of deficiencies (Tsoukatos & Rand, 2007). In high power distance cultures, weak customers maintain a distance between themselves and suppliers since differences between people are marked by their degree of power. As a consequence of their acceptance of inequalities, these customers are likely to set a low level of expectations (Dash et al., 2009). They may be loyal to the supplier no matter how low the level of service is. However, the expectation will be higher in low power distance societies, and loyalty is more difficult to achieve.

In the brand domain, people with high uncertainty avoidance value the brand and its credibility, which leads to brand choice (Erdem et al., 2002), staying with a brand that is already established and rewarding it with loyalty because they fear the risks associated with change and the costs it may have (Erdem et al., 2006). Similarly, uncertainty avoidance affects how loyalty develops in the restaurant, as more change-resistant or risk-averse individuals are more affectively and intentionally loyal (Bartikowski et al., 2011). This is because people with a fear of change continue with the same supplier once they are satisfied (Liu et al., 2001). Han et al. (2021) propose the role of cultural value uncertainty avoidance as a determinant of brand loyalty, confirming the existing significant effect. The following hypotheses are therefore put forward:

H4: there is a positive and direct effect of time orientation on loyalty.

H5: there is a positive and direct effect of power distance on loyalty.

H6: there is a positive and direct effect of uncertainty avoidance on loyalty.

Overall satisfaction is a measure of the degree to which the products or services provided by an organisation meet customer expectations (Ali et al., 2021). Authors such as Uslu (2020) confirmed the effect of satisfaction on intention to generate e-wom about the restaurant. Loyalty is defined as a consumer's favourable attitude toward an organisation and has been studied to understand consumers' intentions to purchase repeatedly and recommend to others (Lai, 2019). In the tourism context, Gallarza and Saura (2006) propose the relationship between satisfaction and loyalty based on the premise that the greater the satisfaction perceived by the customer, the greater the loyalty developed. In the field of restaurants, some authors, such as Cakici et al. (2019) and Zhong and Moon (2020)have also confirmed this relationship.

Satisfaction is an antecedent of brand equity, for example, in the case of electronic products where the green image is analysed (Cheng, 2010), in the mobile phone industry (Guo & Zhou, 2021), as well as in the field of green brands in general (Konuk et al., 2015). The following hypothesis is therefore put forward:

Brand equity being a general brand valuation in reference to the preference for the brand among other alternatives (Aaker, 1991), some authors suggest that brand loyalty and brand equity are closely related (Lili et al., 2022). Thus, the literature highlights the relationship between loyalty and brand equity, derived from the fact that the greater the loyalty towards the brand, the greater the brand equity from the customer's point of view (Shabbir et al., 2017; Sasmita and Suki, 2015). Based on the above, the following working hypotheses are put forward (see figure 1):

3. Methodology

Prior to data collection, a number of restaurants were asked to collaborate by means of a duly motivated letter of presentation in which the objectives of the study and the procedure to be followed if they agreed to participate were presented. In the end, the collaboration was carried out with a restaurant in the south of Spain characterised by a good quality-price ratio and a large capacity.

The data collection method was the self-administered questionnaire inside the restaurant at the end of the customers' dining experience, for which the restaurants were provided with tablets with which they had to fill in an online questionnaire implemented in the Qualtrics platform. All measures used are 7-point Likert measures, adapted from scales of previous studies, whose authors and items are listed in the Appendix.

The final sample obtained was 540 subjects. The socio-demographic details of the sample are presented in table 1.

Table 1 Description of the sample

| Variable | Category | N (%) |

| Gender | Man Female | 277 (51.30%) 263 (48.70%) |

| Age | 18-35 36-45 46-55 56-66+ | 165 (30.55%) 158 (29.26%) 133 (24.64%) 84 (15.55%) |

| Monthly income level | <600€ 600-1200€ 1201-1800€ 1801-2400€ 2401-3000€ 3001-4000€ 4001-5000€ >5000€ | 24 (4.44%) 68 (12.59%) 128 (23.70%) 123 (22.78%) 102 (18.89%) 27 (5.00%) 38 (7.04%) 30 (5.56%) |

4. Results

Before carrying out the hypothesis testing, the psychometric properties of the scales were analysed by means of a CFA using AMOS software. The items OLP5 and OLP6 for presenting an R2 below the recommended 0.5 (Del Barrio and Luque, 2012; Hair et al., 2014). Once the factor model was re-estimated, the results showed that the global indicators were within the recommended limits (Chi-Square: 1218.72; p-value: 0.00; RMSEA: 0.08; CFI: 0.91). Furthermore, all indicators showed significant loadings (p<0.05) and individual reliability (R2) above the recommended value (see table 2). The composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) indicators presented values above the recommended limits of 0.80 and 0.50, respectively, which, together with the statistical significance of the loadings, ensured adequate convergent validity of the constructs. On the other hand, discriminant validity was tested using the criterion of Fornell and Larcker (1981). Table 3 shows that the correlations between latent constructs are not greater than the square root of the variance extracted from each of them (values of the diagonal), concluding the good discriminant validity of the constructs.

Table 2 Analysis of the psychometric properties of the scales.

| Construct | Item | Standardised coefficient | R2 | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long-term orientation | OLP1 | 0.77 | 0.596 | 0.87 | 0.57 |

| OLP2 | 0.82 | 0.682 | |||

| OLP3 | 0.81 | 0.671 | |||

| OLP4 | 0.78 | 0.608 | |||

| Power distance | DPO1 | 0.87 | 0.768 | 0.92 | 0.61 |

| DPO2 | 0.88 | 0.784 | |||

| DPO3 | 0.84 | 0.716 | |||

| DPO4 | 0.89 | 0.802 | |||

| DPO5 | 0.71 | 0.514 | |||

| Uncertainty avoidance | AVERS1 | 0.86 | 0.742 | 0.93 | 0.63 |

| AVERS2 | 0.87 | 0.768 | |||

| AVERS3 | 0.88 | 0.788 | |||

| AVERS4 | 0.82 | 0.684 | |||

| AVERS5 | 0.85 | 0.722 | |||

| Satisfaction | SAT1 | 0.79 | 0.631 | 0.86 | 0.67 |

| SAT2 | 0.89 | 0.795 | |||

| SAT3 | 0.78 | 0.608 | |||

| Loyalty | LEAL1 | 0.85 | 0.726 | 0.92 | 0.67 |

| LEAL2 | 0.87 | 0.765 | |||

| LEAL3 | 0.85 | 0.732 | |||

| LEAL4 | 0.84 | 0.719 | |||

| Brand equity | BE1 | 0.80 | 0.655 | 0.91 | 0.66 |

| BE2 | 0.89 | 0.807 | |||

| BE3 | 0.85 | 0.732 | |||

| BE4 | 0.89 | 0.719 | |||

| Chi-square (f.d.): 1218.72(260); RMSEA: 0.082: CFI: 0.917 | |||||

Table 3 Discriminant matrix

| LTO | PD | UA | SAT | LTY | BE | |

| LTO | 0.75 | |||||

| PD | 0.28 | 0.78 | ||||

| UA | 0.65 | 0.35 | 0.79 | |||

| SAT | 0.42 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0.81 | ||

| LTY | 0.45 | 0.15 | 0.41 | 0.79 | 0.81 | |

| BE | 0.49 | 0.34 | 0.44 | 0.69 | 0.80 | 0.81 |

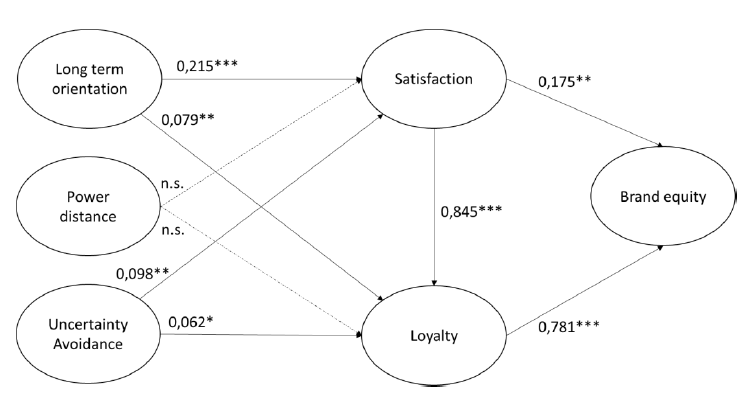

The results show that long-term orientation and uncertainty avoidance have a positive and direct effect on satisfaction (βLong-term orientation->Satisfaction: 0.215; p-value<0.001; βUncertainty avoidance-> Satisfaction: 0.098; p-value<0.05), the effect being greater in the first case, and therefore confirming hypotheses H1 and H3. However, H2, which posited a relationship between power distance and satisfaction, cannot be confirmed, since the coefficient turns out to be non-significant (βPower Distance->Satisfaction: p-value n.s.).

The existence of a significant effect of time orientation on loyalty and a quasi-significant effect of uncertainty avoidance on loyalty is corroborated (βLong-term orientation->Loyalty: 0.079; p-value<0.05; βUncertainty avoidance->Loyalty: 0.062; p-value<0.10), which allows us to confirm hypotheses H4 and H6. However, H5, which posited a relationship between power distance and loyalty, cannot be confirmed, since the coefficient was not significant (βPower distance Loyalty: p-value n.s.).

Satisfaction has a strong determinant effect on loyalty (βSatisfaction->Loyalty: 0.845; p-value<0.001), confirming H7. And finally, the results show significant coefficients in the relationships between satisfaction and Brand equity and between loyalty and Brand equity (βSatisfaction->Brand equity: 0.175; p-value<0.05; βLoyalty->Brand equity: 0.784; p-value<0.001), confirming H8 and H9 (see figure 2).

4.Discussion

In line with the main objective of the research, it has been possible to demonstrate that individual cultural values are powerful determinants of the attitudinal process in consumer behaviour, more specifically of the customer in the restaurant, affecting their satisfaction and loyalty, in line with recent proposals by other authors such as Han et al. (2021).

Of the individual cultural values addressed, only power distance does not affect the attitudinal process, as Han et al. (2021) concluded. This could be translated as follows: the attitude of customers does not depend at all on their degree of assumption of hierarchies. Note that other researchers have shown that the assumption of power distance affects how, for example, the quality of service is assessed (Dash et al., 2009) since expectations vary according to this cultural assumption. For example, expectations will be higher if subjects do not assume hierarchical distances. This negative or inverse relationship has been suggested and contrasted by authors such as Gao et al (2018). These previous studies lead us to think that given that these cognitive aspects (such as the quality of service) precede the attitude that the customer may take - following a theoretical S-O-R sequence (stimulus, organism, response), it can be understood that the non-significant effect obtained would become effective if a cognitive variable with a mediating role were incorporated, such as the quality of the restaurant's service, the food and the environment.

However, satisfaction and loyalty are directly affected by the customer's long-term orientation and uncertainty avoidance, in line with the recent findings of Han et al. (2021). Both satisfaction and loyalty are affected to a greater extent by time orientation, and the speed that customers require within their cultural mindset will directly determine their satisfaction.

As expected, the sequence between the attitudinal process and the formation of brand equity is strongly grounded in theory (Nam et al., 2011; Rodríguez-López et al., 2020), mainly in the order Satisfaction->Loyalty->Brand equity.

5. Conclusions and implications

There are still many unresolved questions in modelling brand equity formation for brands, and more specifically for restaurants. The challenge in providing management recommendations to firms is first to find the best patterns in modelling behaviour that maximise the effects and extend the model's explanatory power for the dependent variable of interest. For this reason, the authors believe that, given the common interest of the research community in finding a model that fits in order to give recommendations, it is often more necessary to clarify theoretical debates and continue deepening research with a more constructivist and deductive approach.

In this sense, the main objective of this work is to apply a sequence of behaviour that has been little studied so far and to try to clarify the role of culture in modelling restaurant customer behaviour.

In relation to the established objectives, the conclusions drawn from this study are the following: firstly, in general terms, the individual cultural dimensions of uncertainty avoidance and long-term orientation play a determining role in satisfaction and loyalty. More specifically, satisfaction is strongly determined by long-term orientation.

This means that the more long-term oriented the customer is, the more likely he/she is to develop satisfaction since this type of customer is oriented towards developing long-lasting relationships (loyalty), which is logically preceded by satisfaction. Therefore, the greater the orientation over time, the greater the customer loyalty and the BE, given that loyalty is closely related to the long term in which customer-restaurant relationships are forged, preference develops, and progressively gives rise to recommendation intentions that will lead to behaviours. On the other hand, uncertainty avoidance means that the greater the customer's fear of risk, the greater the likelihood that he or she will develop loyalty, given that this customer prefers not to change restaurants again. It is logical to think that various stimuli must be taken into account for this effect to occur (the food, the service, the environment).

It is necessary to point out the importance of these results in relation to tourism, a sector whose importance was highlighted in the introductory section. In this sense, with the measure of long-term orientation and uncertainty avoidance at the individual level, the conclusions drawn can be extrapolated to the national cultural sphere, thanks to Hofstede's cultural schema scores for the dimensions discussed, which can be consulted at https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/.

Thus, according to this score, countries such as Spain and Brazil have a high uncertainty avoidance score (86 and 76, respectively), and Denmark has a low score (23). Jordan and Australia are short-term-oriented societies, while Indonesia has a score close to a long-term orientation. This correspondence rule allows conclusions about societies to be drawn from individual cultural measures, which are useful in tourism. Thus, the agents involved in tourism, in general, and restaurants in particular, can design strategies adapted to the culture of inbound tourism. More specifically, a restaurant that receives Spanish tourists should design strategies that dispel Spaniards' fear of the ambiguous or the unknown, for example, by showing the interior of the restaurant before the visit via the web or social networks, as well as the dishes in 3D technology, and all the information that allows the client to dissipate the dissonance between the visit they are planning and the experience they are going to have.

Strategies focused on oriental markets such as the Chinese, oriented to the long term, will be able to design hedonic offers of enjoyment and delight that satisfy the customer and lead to long-term loyalty.

This paper's limitations lie in the model's poor fit, which may have stemmed from the questionnaire and respondent language issues rather than the sample size. We also believe that the calculation of total and indirect effects could have shed more light on the extent to which cultural values are affecting the explainability of brand equity in this model.