1. Introduction

The EU Pact for Skills Strategy (European Commission, 2020a) was launched as one of the essential flagship actions under the European Skills Agenda to support the twin transition to a green and digital economy, strongly underpinned by the European Pillar of Social Rights launched by the European Commission in 2017 (European Commission, 2022). The tourism sector was highlighted as one of fourteen industry sector ecosystems identified by the European Industrial Strategy (European Commission, 2020b). The Pact for Skills calls on industry, employers, social partners, Chambers of Commerce, public authorities, vocational education and training providers, higher education institutions and employment agencies to collaborate and commit to training investment for current and future employees of all ages in Europe using a multi-stakeholder skills partnership. This aligned with the first principle of the European Pillar for Social Rights focuses on Education, training, and life-long learning.

Considering the importance of skills, the European Commission decided to make 2023 the European Year of Skills to prepare for the “twin transition” that will require a remarkable shift in skill sets. The twin transition reflects how digital and green (environmental) transformations in industry and the use of resources within the natural environment require the development of specific skills to drive new economic and social settings but also demand transversal soft skills that enable people to successfully navigate changing environments to better engage in work, society and democracy.

According to recent Eurostat statistics, hospitality and tourism jobs and investments within the industry are driving EU growth (Weforum, 2022; Eurostat, 2022). Despite the abrupt closure of the industry during the Covid-19 pandemic, there is an unprecedented recovery and continuation of pre-pandemic demand for tourism. However, there are distinct labour shortages across the sector in countries across Europe. Therefore, training and education to support the sector is important not only to assist the recovery of the industry post Covid-19, but also to ensure that employees have the right social skills to boost the digital and green transition that is so urgently needed and support social relations. Hence it is critical to identify the skills gaps from the viewpoint of the public and private stakeholders.

This paper aims to present a detailed assessment of social skills gaps in the European tourism industry reflecting both the current and future status of employee skills. The research, undertaken during the Next Tourism Generation Alliance Erasmus + European Commission funded Project (2018-2022), begins with a thorough revision of the literature to understand the meaning and importance of social skills for the tourism and hospitality industry. Extensive survey data collection was completed with 1404 owners and managers of tourism and hospitality businesses and Destination Management Organisations (DMOs) in eight different European Countries to assess social skills gaps. The paper then analyses the perceptions of social skills gaps, paying attention to variances between countries, and the importance of these social skills in relation to employee roles and responsibilities. Finally, the paper provides an understanding of how these social skills gaps relate to European policy initiatives and the challenges providing social skills training. These factors of skills gaps and policy implementation are particularly relevant when considering contextually appropriate training that is pertinent to the local culture, attitudes and behaviours in society where training takes place. This in turn can support upskilling or updating skills and encourage current and future employees to train for new skills (reskilling).

Social (soft) skills are used in this paper as an umbrella term comprising the following categories: personal/interpersonal skills; communication skills and cross-cultural and diversity awareness skills that foster cultural, emotional, and labour intelligence which provided the adopted terminology for the survey.

2. Literature review

2.1 The importance of social skills

Cultural as well as social diversity continues to permeate every aspect of life as the world becomes more interconnected through processes of migration, urbanisation, and digitalisation. It is the socio-cultural aspect of tourism that necessitates soft skills as a primary element of the tourism industry. Additionally, meeting the demands of modern life will require a “higher level of mental complexity that implies critical thinking and a reflective and holistic approach to life” (Rychen & Salganik, 2003. Huang et al. (2021) also encourages a greater level of recognition of the importance of critical thinking and social perceptiveness in the hospitality sector which requires sensitivity and empathy towards colleagues and customers. The tourism industry, as “the most visible expression of globalization” (Reseinger, 2009, p. 8) presents its own challenges with trends pointing towards growing international ownership, increasing migration, changes in demographics, with more women and ethnic minorities entering the labour market, a shift in global power from West to East, and the appearance of new age cohorts due to changes in life expectancy and lifestyle (Espeso-Molinero, 2019; Reseinger, 2009). Understanding the diversity that characterises hosts and guests in the XXI century therefore becomes paramount. In these circumstances “it has become increasingly important that students enter the workforce prepared to deal with diversity and multicultural issues” (Rivera & Lee, 2016, p. 156). Social skills are therefore critically important to support this end and comprise a key social element of sustainable tourism (Baum 2018; Carlisle et al., 2021; Devile et al., 2023; Habimana et al., 2023; Mooney et al., 2022; Mínguez et al., 2021).

There are a vast range of terminologies for social skills or people skills including what authors have termed soft, human, personal, interpersonal, emotional skills or in some cases XXI Century skills, as well as diversity aware or awareness-based skills. Since the 1980s a growing body of literature reflects the relevance of soft skills in different domains and in tourism, it has been studied in the lodging sector (Sisson & Adams, 2013; Magalhães et al., 2023), outdoors, parks and recreation (Baker & O’Brien, 2017; Chase & Masberg, 2008; Leister, 2019; Shooter et al., 2009), food and beverage (Nyanjom & Wilkins, 2016; Sisson & Adams, 2013), airlines companies (Flin, 2010), museums (Theriault & Ljungren, 2022), meetings and events (Sisson & Adams, 2013) and tourism education (Crawford et al., 2020; Daniel et al., 2017; Mínguez et al., 2021; Wang & Tsai, 2014).

The complexity in terminology, conceptualization, taxonomies, and frameworks around these social or human abilities and competencies frequently overlap, generating confusion and potentially making operationalisation difficult. Despite differences, the literature often reflects on similar underlying concepts that are used interchangeably (Sanchez Puerta et al., 2016). From a pragmatic, rather than ideological or disciplinary perspective, Duckworth & Yeager (2015, p. 239) clarify the concept of soft skills by describing its attributes as:

conceptually independent from cognitive ability, (b) generally accepted as beneficial to the student and to others in society, (c) relatively rank-order stable over time in the absence of exogenous forces (e.g., intentional intervention, life events, changes in social roles), (d) potentially responsive to intervention, and (e) dependent on situational factors for their expression.

The tourism literature notably reflects the importance of soft skills over hard skills for the service industry (Haven-Tang & Jones 2008; Marneros et al., 2023; Sisson & Adams, 2013). Soft skills are considered of vital importance for entrepreneurship (Lamineet al., 2014; Daniel et al., 2017; Koc, 2020), innovation (Cobo, 2013), multicultural competence (Chrobot-Mason & Leslie, 2012), diversity awareness (Devile et al., 2023), emotional intelligence (Chrobot-Mason & Leslie, 2012; Emmerling & Boyatzis, 2012), employability (Chan, 2011; Taylor, 2005; Wang & Tsai, 2014; Zwane et al., 2014) or sustainability (Kiryakova-Dineva et al., 2019; Mooney et al., 2022).

2.2 European Policy on Skills Development

Considering the importance of skills development, the European Commission has set a plan to ensure that training and lifelong learning, becomes a reality for all EU citizens helping individuals and business to attain the needed skills. The European Skills Agenda for sustainable competitiveness, social fairness and resilience launched in 2020 and the European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan (2021) aims to strengthen the social dimension of the European Union by supporting a fair recovery from the health and economic crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and ensure a “strong social Europe for just transitions”.

Among other measures, the European Skills Agenda is promoting the Pact for Skills, which also aligns with the OECD (2019) Policy and Strategy for Future Education and Skills 2030. The Pact for Skills Strategy is the first of the twelve flagship actions of the Skills Agenda and intends to encourage public and private organisations to commit and work collaboratively towards upskilling and reskilling the European workforce. Four broad principles give structure to the Pact for Skills, namely (1) promoting a culture of lifelong learning for all; (2) building strong skills partnerships; (3) monitoring skills supply/demand and anticipating skills needs; (4) working against discrimination and for gender equality and equal opportunities. The European Union offers the signatories three specific support services to help them adopt these principles, the Networking Hub to find partners, promote their activities and find useful EU tools; the Knowledge Hub to share learning activities, expertise and best practices; and the Guidance Hub to better understand the possibilities of funding.

In December 2021 the EU Pact for Skills Strategy (2021) was integrated into the tourism and hospitality sector with the Skills Partnership for the Tourism Ecosystem with support from the NTG Alliance and signed by industry actors, public authorities, educational providers and social organisations to take action to upskill and reskill the tourism workforce in Europe. The Strategy highlights the challenges of a highly fragmented industry, where 90% of the companies employ less than 10 people; an elevated turnover due to seasonality and short-term contracts; a workforce less qualified than the EU average, with a quarter of the employees considered to have low-level qualifications; and an industry severely impacted by the Covid-19 crisis.

Meanwhile, the shortage of hospitality and tourism workers is hitting mature world-wide destinations, a trend occurring before the Covid-19 pandemic (see Baum, 2018). A recent WTTC study (2021) on six mature tourism markets showed important staff shortages after the pandemic restrictions ended. Whilst the travel and tourism industries are recovering in the US, the UK, Spain, Portugal, France and Italy, job vacancies cannot be filled. Former employees are moving to other sectors and the perceived poor labour conditions of the tourism and hospitality industries deter job seekers from entering the trade. To address these issues the WTTC recommends facilitating labour mobility and remote work, ensuring decent work conditions, providing social safety nets, retaining talent through upskilling and reskilling the workforce, and finally creating and promoting education and apprenticeships.

2.3 Identifying social skills for sustainable tourism: A Theoretical Framework

To implement the Pact for Skills Strategy and be prepared to support the upskilling and reskilling of the workforce, it is critically important to understand the relevant social skills needed in the tourism ecosystem. There is a wide range of research that represents views as to what constitutes a valuable and useful set of skills and competencies for tourism and hospitality service industries (see Tracey, 2014; Weber et al., 2012; Weber et al., 2013; Weber et al., 2020). To deliver meaningful experiences for tourists, service provider employees need to embody certain abilities. Given the high level of occurrence of tourist and employee interface Johanson et al. (2011) highlight communication, customer focus, interpersonal skills, and leadership as essential employee skill requirements for hospitality services. After developing a list of 117 potentially needed skills, Sisson & Adams (2013) identified 33 skills, competencies, and abilities applicable across the areas of lodging, food and beverage, and meetings and events. For them the essential four soft skills in the industry are the capacity to foster positive customer relations, working effectively with peers, professional demeanour, and leadership.

Rivera & Lee (2016) emphasise the importance of multicultural, diversity education and Emotional Intelligence (EI) in tourism services as key indicators of managerial effectiveness. This underpins social elements of sustainable tourism to support a just and respectful destination society and industry where tourists, employees and residents interact whatever their race, religion, age, nationality or physical ability. Based on previous studies that showed that managers with high degrees of EI handled better inter-group conflicts (Chrobot-Mason and Leslie, 2012) and is a predictor of success (Scott-Halsell et al., 2013), they showed the importance of awareness and understanding of other cultures to contribute to managers’ emotional intelligence while Sariego López & Mazarrasa Mowinckel (2020) analyse key competences for cultural awareness. Kiryakova-Dineva et al. (2019) emphasise that “hospitality, professional behaviour and employee motivation are marked as the most important soft skills”. Meanwhile employees rated “responsibility, self‐esteem, sociability, and working with diverse groups” as the more important social skills needed in hospitality services (Kim et al., 2011, p. 739). A UK study on the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic, showed that besides skills related to health and security, employers of the hospitality, retail, travel and aviation services rated highly “softer skills such as being aware of changing needs, actively looking for ways to help and managing uncertainty” (Enback, 2020, p. 3).

After a thorough revision of the literature, Weber et al. (2013) identified 107 competencies combined into seven categories of soft skills, namely communication /persuasion, performance management, self-management, leadership/organisation, interpersonal, political/cultural and what they called counterproductive or negative soft skills. This latter set of traits trigger uncomfortable work environments, low levels of job satisfaction and high turnover of staff. Results from their study show that “employees are less likely to respond in a positive manner to a manager that micromanages, acts aggressively, or makes inappropriate comments” (Weber et al., 2013, p. 325) thereby encouraging the importance of leadership skills to navigate strengths and weaknesses of employees and support the social pillar of sustainable tourism via employee relations to support good working conditions, respect for gender equality and host and guest relations.

For this research we therefore investigated social skills gaps that can help to implement sustainable tourism principles, using the categories: personal/interpersonal skills (problem solving, initiative and commitment, customer orientation, ethical conduct and respect, willingness to change, promoting a positive work environment, creativity, and willingness to learn and to perform); communication and cross-cultural skills (written and oral communication skills, active listening skills, skills related to cultural awareness and expression, skills related to awareness of local customs, ability to speak foreign languages, and skills related to intercultural host-guest understanding and respect); and diversity and awareness skills (gender equality skills, age-related accessibility skills, diets and allergy needs skills, skills related to disabilities and appropriate infrastructure, skills related to diversity in religious beliefs).

2.4 Training for Social Skills

In the tourism sector “there is still a lack of tools that support soft skills, including how to increase tourists’ engagement, experience and satisfaction” (Leister, 2019, p.3). Even though managers agree that these skills ensure efficiency and productivity in the tourism industry, they are generally not found on job descriptions (Tsalikova & Pakhotina, 2019). Traditionally soft skills were “typically developed through personal experience and reflection” (Dixon et al., 2010, p.35) while hard skills were at the core of formal education and vocational training. Nevertheless, the relevance of training and teaching soft skills has been gaining precedence in the business as well as the education literature of tourism, and traditional or mature as well as emerging destinations are including soft skills in their tourism programs (Koc, 2020; Marinakou & Giousmpasoglou, 2015; Mínguez et al., 2023; Sisson & Adams, 2013; Spowart, 2011).

Quite often “emotion work is largely invisible and thus lacks acknowledgement and training” (Baker & O’Brien, 2017, p.3). There are several challenges that hinder this. Nickson et al., (2003) highlights that it is not easy to accredit formal qualifications for soft skills. Chan (2011) signals the need to incorporate soft skills into the student curricula, the importance of training for educators and professionals to translate the skills, and the perception of soft skills by the students. Other authors consider that the skills gap comes from “supply led training instead of demand-driven training” (Francis et al., 2020), as many training providers do not really understand the need for soft skills in the professional market (Cullen, 2011). Therefore, it is critically important to foster stronger links between the industry and educational institutions (Francis et al., 2020).

Bailly & Léné (2013, p.80) argue that “the rise to prominence of soft skills has been accompanied by the increasing personification of the service labour process” which bring important challenges to employee recruitment and training, for instance, the perception of soft skills as innate or acquirable. When the employer or the employee considers these attributes as innate to individuals, they may disregard education or training and be less inclined to invest money or effort in its procurement. Under this idea, employees can be hired on an ‘as needed’ basis, with just the “right” skills for the job. The personification of skills can also lead to the personification of errors and weaknesses in service provision and workers can be held accountable for their own professional destinies, liberating firms of any responsibility for training, subsequently entering the “skills deficit blame game” (Hurrell, 2016). On the other extreme, when soft skills are considered malleable, companies may be inclined to adopt “corporate production” of aesthetic and emotional labour, where firms seek to mould their workforce, especially entry level employees, into their desired personas, fully identifying with the company image and ethos (Bailly & Léné, 2013).

Evidence also shows that “non-cognitive skills can be enhanced, and there are proven and effective ways to do so” (Kautz et al., 2014, p. 65), however “there is a lack of understanding of how these skills should be translated and operationalized for students in the classroom” (Crawford et al., 2020, p.1) or on the job training. To strengthen soft skills, authors insist on the importance of student-centred approaches in tourism and hospitality education (Zehrer & Mossenlechner 2009; Chan, 2011; Ricchiardi & Emmanuel 2018) with opportunities to solve real-life problems through active learning (Crosbie, 2005), experiential learning (Crawford et al., 2020), and business simulations (Levant et al., 2016). Singh & Jaykumar (2019) insist on the significance of internships while Kim et al. (2011) explore the use of e-learning to train soft skills. Crawford et al. (2020) analyse the way hospitality managers teach soft skills needed in the working environment trying to translate the techniques and systems employed in the professional world to the classroom. Theatre-based training can help students improve awareness of self and others, internalise cultural differences through role playing and develop creativity, communication (Baccarani & Bonfanti, 2016) and other soft skills needed for the hospitality industry. For Lundberg & Mossberg (2008) engaging in communication among fellow front-line colleagues prove to be vital in developing the social skills needed for creating successful service encounters. On the other hand, social anxiety and avoidance limits the acquisition of soft skills (Koc, 2019) which is also a key concern following social isolation during Covid-19.

3. Methodology

This paper presents exploratory social skills gaps research which was completed as part of the Next Tourism Generation (NTG) Alliance project funded by the KA 2 Erasmus+ Programme (https://nexttourismgeneration.eu/). The research populations included businesses including accommodation, visitor attractions, food and beverage outlets, tour operators and travel agents, and destination management organisations (DMOs) registered in eight European countries (Bulgaria, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, and the UK). The country-based surveys reflect the geographic scope of NTG Alliance partners, which included seven tourism and hospitality trade associations and six tourism and hospitality vocational education universities. The scope of the subsectors was determined by the parameters of the NTG project.

This paper presents anonymous online Qualtrics survey data collected in 2019 using a quantitative research design. Ethics approval was provided by Cardiff Metropolitan University Research Ethics committee (ref 2019S0001) in which research ethics and associated deontological principles including respondent confidentiality and anonymity, survey distribution, sampling, survey risks and professional design of the survey were critically evaluated. There are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report. The web link to the survey was distributed to senior managers of businesses and DMOs via contacts in the tourism and hospitality trade associations, business networks and social media groups throughout the eight sampled countries. The managers were identified as most knowledgeable respondents about the current level of social skills and the future skills needs in their companies according to their experience of management and supervision of their employees. To increase participation in the survey it was translated from English into six different languages (Italian, Spanish, Dutch, German, Hungarian, and Bulgarian). The sample included 1404 respondents (see Table 1).

Table 1 Sample’s characteristics

| Characteristic | Number of respondents | Share (%) |

| Country | ||

| Italy | 370 | 26.4 |

| Germany | 246 | 17.5 |

| UK | 233 | 16.6 |

| Spain | 139 | 9.9 |

| Bulgaria | 135 | 9.6 |

| Hungary | 123 | 8.8 |

| Ireland | 74 | 5.3 |

| Netherlands | 40 | 2.8 |

| Other | 44 | 3.1 |

| Sector | ||

| Accommodation | 525 | 37.4 |

| Destination management | 295 | 21 |

| Visitor attractions | 212 | 15.1 |

| Food & beverage | 201 | 14.3 |

| Travel agents and tour operators | 171 | 12.2 |

| Size | ||

| Large (250 or more employees) | 128 | 9.1 |

| Medium (100-249 employees) | 128 | 9.1 |

| Small (10-99 employees) | 512 | 36.5 |

| Micro (Less than 10 employees) | 501 | 35.7 |

| Individual or part-time activity | 135 | 9.6 |

| Total | 1404 | 100 |

The survey consisted of four main sections. The first section asked respondents about the characteristics of their organisations, country of registration, type, size, tourism sector, and their job position. The next two sections asked respondents about the current and the required future proficiency levels for digital, environmental, and social skills. The last section was dedicated to the training provided by the organisation to enhance the surveyed skill sets. This paper focuses on the social skills, whilst the digital and environmental skills findings are reported in other publications stemming from this same survey (see Carlisle et al., 2021, 2022, 2023). The NTG project differentiated these skill sets according to the European Commission Blueprint strategy requirements which reflect key categories of skill sets in which significant gaps persist in society. Importantly communication and inter-personal skills also compliment digital literacy and technology adoption for example in the development of accessible website content or Augmented Reality supported applications. Environmental Management Systems (EMS) and behavioural change within organisations requires extensive communication and listening skills to be able to interpret and effectively communicate key messages and management practices which support conservation of scarce resources, reduction of carbon emissions and plastic pollution and ensure financial savings as well as environmental protection.

The social skills categories were determined by the consortium members’ research and industry experience and via a comprehensive review of academic, policy and trade press publications. The proficiency level was assessed on a 5-point scale - from 1 (not any social skills) to 5 (excellent level of social skills). The senior managers self-assessed the level of proficiency of each social skill set in their organisation similar to prior research (see, for example, Castro & Ferreira, 2019). This was due to firstly, the time and financial constraints which did not permit the evaluation of the actual proficiency levels of all employees of all 1404 businesses and DMOs in the sample. Secondly, the senior managers were agreed to be the most knowledgeable respondents to provide a realistic account of the proficiency levels of the social skills of employees for whom they line managed.

The skewness and kurtosis values were within the range [-1; +1]. That is why, considering the large sample size (>500), the distribution of respondent’s answers was assessed as close to normal (George & Mallery, 2019; Kim, 2013). In this regard parametric tests were used for data analysis (e.g. paired samples t-test and ANOVA). Exploratory factor analysis was implemented to explore the relationships between the social skills gaps. Cluster analysis helped to identify groups of respondents based on their social skills gaps. The number of respondents in the cluster analysis (1404) was 70 times larger than the number of variables used in the segmentation base (20) which is the minimum ratio recommended by Dolnicar et al. (2014).

4. Results

4.1 Overall analysis

Table 2 shows the current level and future required proficiency level of social skills and the absolute and percentage gaps between them. Survey respondents reported the highest proficiency levels in Customer orientation (m=4.19) and Ethical conduct (m=4.14) while Ability to speak foreign languages (m=3.28) and Skills related to diversity in religious beliefs (m=3.37) had the lowest level of proficiency. The paired samples t-tests between the self-reported current level of proficiency for these four social skill and other skills were all significant at p<0.001 (not reported in the paper but available upon request). In regard to the required future level of the social skill, the same skills occupy the top and the bottom places: Customer orientation (m=4.55), Ethical conduct (m=4.45), Ability to speak foreign languages (m=4.03), and Skills related to diversity in religious beliefs (m=3.99), while Promoting a positive work environment (m=4.44) ranks high as well. Ability to speak foreign languages (absolute gap=0.75, percentage gap=22.87%) and Skills related to disabilities and appropriate infrastructure (absolute gap=0.69, percentage gap=19.77%) are the skills with the greatest perceived deficits, while the reported gaps are the smallest for Customer orientation (absolute gap=0.36, percentage gap=8.59%) and Ethical conduct (absolute gap=0.31, percentage gap=7.49%). All gaps are positive, meaning that the respondents considered that they their current proficiency levels at each of the social skills in this study is lower than the level they think would be required in the future. Moreover, all the paired samples t-tests between the current and future levels of proficiency are significant at p<0.001 (see the last column of Table 2).

Table 2 Current level of proficiency and future required proficiency level of soft skills

| Soft skills | Current level | Future level | Absolute gap (future level/current level) | Percentage gap (Absolute gap/Current level) | Correlation between Current and Future levels | Paired samples t-test (Current vs Future level) | |||

| Mean | Standard deviation | Mean | Standard deviation | Mean | Standard deviation | ||||

| Personal skills | |||||||||

| Problem solving | 3.86 | 0.864 | 4.32 | 0.808 | 0.46 | 0.744 | 11.92% | 0.606*** | -23.101*** |

| Initiative and commitment | 3.97 | 0.856 | 4.36 | 0.774 | 0.39 | 0.780 | 9.82% | 0.546*** | -18.744*** |

| Customer orientation | 4.19 | 0.826 | 4.55 | 0.715 | 0.36 | 0.763 | 8.59% | 0.518*** | -17.562*** |

| Ethical conduct and respect | 4.14 | 0.824 | 4.45 | 0.749 | 0.31 | 0.736 | 7.49% | 0.566*** | -15.557*** |

| Willingness to change | 3.77 | 0.955 | 4.36 | 0.790 | 0.59 | 0.911 | 15.65% | 0.468*** | -24.108*** |

| Promoting a positive work environment | 3.97 | 0.895 | 4.44 | 0.765 | 0.46 | 0.817 | 11.59% | 0.524*** | -21.290*** |

| Creativity | 3.83 | 0.951 | 4.33 | 0.807 | 0.50 | 0.849 | 13.05% | 0.544*** | -22.196*** |

| Willingness to learn and to perform | 3.99 | 0.913 | 4.42 | 0.786 | 0.43 | 0.809 | 10.78% | 0.556*** | -19.769*** |

| Communication and cultural skills | |||||||||

| Written communication skills | 3.81 | 0.854 | 4.22 | 0.825 | 0.41 | 0.801 | 10.76% | 0.545*** | -19.259*** |

| Oral communication skills | 3.96 | 0.804 | 4.35 | 0.780 | 0.39 | 0.803 | 9.85% | 0.487*** | -18.188*** |

| Active listening skills | 3.79 | 0.851 | 4.32 | 0.784 | 0.53 | 0.868 | 13.98% | 0.438*** | -22.837*** |

| Skills related to cultural awareness and expression | 3.61 | 0.914 | 4.26 | 0.815 | 0.64 | 0.881 | 17.73% | 0.486*** | -27.364*** |

| Skills related to awareness of local customs (e.g., food, arts, language, crafts) | 3.88 | 0.907 | 4.33 | 0.803 | 0.46 | 0.832 | 11.86% | 0.532*** | -20.508*** |

| Ability to speak foreign languages | 3.28 | 1.092 | 4.03 | 1.018 | 0.75 | 0.978 | 22.87% | 0.572*** | -28.709*** |

| Skills related to intercultural host-guest understanding and respect | 3.72 | 0.960 | 4.28 | 0.860 | 0.56 | 0.871 | 15.05% | 0.546*** | -23.960*** |

| Diversity skills | |||||||||

| Gender equality skills | 3.84 | 0.974 | 4.26 | 0.884 | 0.42 | 0.841 | 10.94% | 0.594*** | -18.755*** |

| Age-related accessibility skills | 3.77 | 0.949 | 4.28 | 0.851 | 0.51 | 0.868 | 13.53% | 0.539*** | -22.203*** |

| Diets and allergy needs skills | 3.51 | 1.142 | 4.08 | 1.052 | 0.57 | 0.858 | 16.24% | 0.697*** | -24.966*** |

| Skills related to disabilities and appropriate infrastructure | 3.49 | 1.031 | 4.18 | 0.905 | 0.69 | 0.964 | 19.77% | 0.510*** | -26.896*** |

| Skills related to diversity in religious beliefs | 3.37 | 1.096 | 3.99 | 1.025 | 0.62 | 0.908 | 18.40% | 0.635*** | -25.473*** |

Notes: N=1404; Level of significance: ***p<0.001; **p<0.01, *p<0.05; Coding - 1-no skills present, 5-expert.

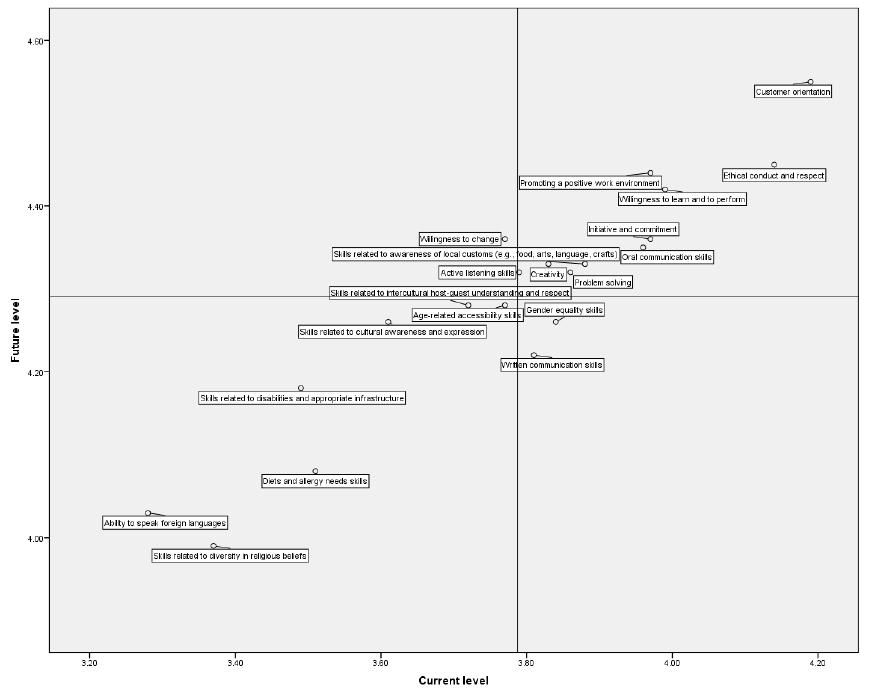

Looking at Table 2 an interesting phenomenon is observed - the self-reported current proficiency level and the required future proficiency level of each social skill are positively, strongly and significantly correlated (min ρ=0.438, max ρ=0.697, all p<0.001). These findings are supported by Figure 1 that maps the mean responses of the current and the future levels of each skill. Therefore, a potential anchoring bias (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974) might exist: respondents’ perceptions about the future social skills requirements are based on their perceptions of their current proficiency levels. However, our data do not allow us to confirm or reject this conjecture.

4.2 The role of country of registration, tourist sector and organisation size

Table 3a presents the ANOVA results based on the country of registration of the organisation the respondents work for, its tourism sector, and size, while Table 3b provides the respondent groups with the highest and lowest mean values of the respective skill. The results show that these three factors shape the self-reported current proficiency level, the required future proficiency level and the absolute gap between them, because most of the F-test values are statistically significant. The role of the specific sector and organisation size was less important in determining the differences in responses about the required future proficiency because less than a third of the respective F-test values were statistically significant, but quite significant in the current proficiency levels and the absolute skills gaps.

Table 3a Differences among respondents based on tourist sector and size

| Soft skills | ANOVA (F-test values) | ||||||||

| Current level | Future level | Absolute gap | |||||||

| Country | Sector | Size | Country | Sector | Size | Country | Sector | Size | |

| Personal skills | |||||||||

| Problem solving | 4.494*** | 5.650*** | 1.185 | 2.131* | 3.307** | 0.820 | 2.721** | 1.948 | 4.124** |

| Initiative and commitment | 3.308*** | 2.549* | 4.840*** | 3.391*** | 1.215 | 0.582 | 1.548 | 1.631 | 5.226*** |

| Customer orientation | 3.757*** | 9.512*** | 0.964 | 2.491* | 2.110 | 2.859* | 2.125* | 5.610*** | 4.837*** |

| Ethical conduct and respect | 5.726*** | 8.844*** | 5.856*** | 4.251*** | 2.254 | 0.372 | 4.494*** | 4.230** | 9.516*** |

| Willingness to change | 10.288*** | 7.012*** | 13.902*** | 4.211*** | 1.776 | 0.360 | 10.095*** | 12.585*** | 12.737*** |

| Promoting a positive work environment | 5.078*** | 6.555*** | 11.215*** | 3.969*** | 2.356 | 0.604 | 3.008** | 4.177** | 12.263*** |

| Creativity | 6.065*** | 6.237*** | 11.933*** | 4.148*** | 0.847 | 2.908* | 2.906** | 4.031** | 4.991*** |

| Willingness to learn and to perform | 7.019*** | 2.800* | 10.053*** | 6.366*** | 0.922 | 0.680 | 3.016** | 2.633* | 9.279*** |

| Communication and cultural skills | |||||||||

| Written communication skills | 1.907 | 13.048*** | 6.603*** | 1.579 | 5.680*** | 1.675 | 1.348 | 4.655*** | 4.696*** |

| Oral communication skills | 5.197*** | 4.357** | 11.519*** | 3.096** | 2.301 | 1.085 | 2.441* | 3.012* | 9.733*** |

| Active listening skills | 6.857*** | 3.670** | 15.054*** | 3.469*** | 1.481 | 0.941 | 3.920*** | 4.136** | 12.956** |

| Skills related to cultural awareness and expression | 4.007*** | 6.558*** | 9.626*** | 5.563*** | 1.405 | 2.780* | 2.748** | 5.817*** | 9.560*** |

| Skills related to awareness of local customs (e.g., food, arts, language, crafts) | 5.295*** | 3.083* | 15.215*** | 3.644*** | 1.354 | 3.637** | 1.533 | 2.517* | 10.258*** |

| Ability to speak foreign languages | 30.843*** | 14.263*** | 1.087 | 21.698*** | 6.130*** | 3.997** | 4.818*** | 4.117** | 2.332 |

| Skills related to intercultural host-guest understanding and respect | 14.159*** | 7.658*** | 5.439*** | 4.552*** | 2.435* | 1.839 | 5.673*** | 3.114* | 6.847*** |

| Diversity skills | |||||||||

| Gender equality skills | 4.347*** | 4.164** | 1.518 | 3.033** | 1.552 | 3.627** | 4.781*** | 1.709 | 4.914*** |

| Age-related accessibility skills | 3.182*** | 1.234 | 1.211 | 1.982* | 0.216 | 2.081 | 6.175*** | 1.286 | 3.897** |

| Diets and allergy needs skills | 12.483*** | 43.305*** | 1.163 | 13.632*** | 27.442*** | 1.039 | 2.913** | 5.032*** | 3.319** |

| Skills related to disabilities and appropriate infrastructure | 6.512*** | 5.008*** | 0.466 | 3.783*** | 1.346 | 3.942** | 3.827*** | 3.973** | 1.717 |

| Skills related to diversity in religious beliefs | 6.176*** | 7.131*** | 0.766 | 5.694*** | 3.142* | 0.310 | 6.376*** | 2.547* | 2.050 |

Notes: N=1404; Level of significance: ***p<0.001; **p<0.01, *p<0.05.

Table 3b Differences among respondents based on country of registration, tourist sector and size Respondent groups with the lowest and highest mean value

| Soft skills | Respondents with the lowest and highest mean value | ||||||||

| Current level | Future level | Absolute gap | |||||||

| Country | Sector | Size | Country | Sector | Size | Country | Sector | Size | |

| Personal skills | |||||||||

| Problem solving | Netherl. Germany | TOTA F&B | Micro Small | Ireland Spain | TOTA F&B | Medium Individual | Germany Hungary | DMO TOTA | Medium Individual |

| Initiative and commitment | Netherl. Spain | TOTA F&B | Individual Large | Ireland Spain | TOTA VA | Small Medium | Other Netherlands | F&B TOTA | Large Individual |

| Customer orientation | Netherl. Germany | TOTA VA | Individual Large | Ireland Italy | TOTA VA | Medium Individual | Germany Hungary | DMO TOTA | Medium Individual |

| Ethical conduct and respect | Italy Germany | TOTA DMO | Individual Medium | Ireland Germany | TOTA DMO | Small Individual | Ireland Hungary | DMO TOTA | Medium Individual |

| Willingness to change | Italy Germany | TOTA DMO | Individual Medium | Ireland Spain | TOTA VA | Micro Medium | Germany Spain | DMO ACC | Medium Individual |

| Promoting a positive work environment | Italy Germany | TOTA DMO | Individual Medium | Ireland Germany | TOTA DMO | Small Large | Ireland Italy | DMO ACC | Medium Individual |

| Creativity | Italy Germany | TOTA DMO | Individual Medium | Ireland Spain | TOTA DMO | Individual Medium | Ireland Netherlands | DMO TOTA | Large / Medium Individual |

| Willingness to learn and to perform | Ireland Germany | TOTA DMO | Individual Medium | Ireland Spain | TOTA VA | Macro Large | Netherlands Spain | DMO VA | Medium Individual |

| Communication and cultural skills | |||||||||

| Written communication skills | Italy Other | TOTA F&B | Individual Large | Italy Hungary | TOTA F&B | Medium Individual | Other Hungary | F&B VA | Large Individual |

| Oral communication skills | Ireland Spain | TOTA DMO | Individual Large | Ireland Hungary | TOTA F&B | Small Large | Other Hungary | DMO VA | Large Individual |

| Active listening skills | Italy Spain | TOTA DMO | Individual Large | Ireland Hungary / Germany | TOTA VA | Small Large | Ireland Italy | DMO VA | Large Individual |

| Skills related to cultural awareness and expression | Bulgaria Hungary | TOTA F&B | Individual Large | Ireland Spain | TOTA ACC | Small Medium | Ireland Netherlands | F&B VA | Small Individual |

| Skills related to awareness of local customs (e.g., food, arts, language, crafts) | Italy Spain | TOTA F&B | Individual Large | Italy Netherla. | TOTA ACC | Individual Large | Other Netherlands | F&B VA | Medium Individual |

| Ability to speak foreign languages | Other UK | TOTA F&B | Medium Individual | Bulgaria Ireland | TOTA F&B | Small Individual | Germany Netherlands | DMO TOTA | Small Medium |

| Skills related to intercultural host-guest understanding and respect | Bulgaria UK | TOTA DMO | Individual Large | Ireland Spain | TOTA VA | Small Medium | Ireland Bulgaria | DMO TOTA | Large Individual |

| Diversity skills | |||||||||

| Gender equality skills | Hungary Netherl. | TOTA DMO | Individual Large | Ireland Netherl. | TOTA DMO | Small Micro | Ireland Hungary | F&B TOTA | Large Micro |

| Age-related accessibility skills | Hungary Ireland | VA DMO | Micro Large | Ireland Netherl. | F&B VA | Small Individual | Ireland Hungary | DMO VA | Small Micro |

| Diets and allergy needs skills | Hungary Germany | F&B DMO | Micro Medium | Ireland Germany | F&B DMO | Small Medium | Ireland Netherlands | DMO F&B | Large Individual |

| Skills related to disabilities and appropriate infrastructure | Italy Netherl. | F&B DMO | Small Medium | Ireland Netherl. | F&B TOTA | Small Individual | Ireland Italy | DMO VA | Large Individual |

| Skills related to diversity in religious beliefs | Bulgaria Ireland | ACC DMO | Individual Large | Bulgaria Netherl. | F&B DMO | Medium Micro | Ireland Spain | DMO VA | Large Individual |

Notes: 1. Lowest values in italic, highest values in bold. 2. Abbreviations: DMO - destination management organisations, F&B - food and beverage, VA - visitor attractions, TOTA - tour operators and travel agents, ACC - accommodation establishments.

In Table 3b interesting patterns emerge. Tour operators and travel agents and self-employed individuals seem to be most confident about their current level social skills, while managers of DMOs and of medium and large organisations considered that their organisations lacked some aspects of social skills. Dutch and Italian respondents reported highest current proficiency level of personal skills while the German respondents were least confident about the personal skills proficiency in their organisations. Most of the F-test values of the current skills levels were statistically significant. Regarding the required future soft skills proficiency levels most differences were observed based on the country of registration of the organisation. Irish respondents put greatest emphasis on the social skills and reported highest required proficiency levels for 16 out of 20 analysed skills and all but one F-test values were statistically significant. DMOs, large and medium-sized organisations had the largest absolute gaps in their social skills, while Hungarian respondents and individual entrepreneurs reported the smallest gaps.

4.3 Factor analysis

The exploratory factor analysis based on the social skills gaps in Table 4 demonstrates how the social skills can be grouped into three factors that entirely overlap with the groups of social skills that were initially formulated by the NTG Consortium members. This means that the gaps in the skills in each of the three groups (personal skills, communication and cultural skills, and diversity skills) were strongly related to the gaps in the other skills in the same groups. Overall, the three factors explained 59.059% of the variation in respondents’ answers and all factor loadings were above 0.500 (min=0.557, max=0.779). The three factors had a very high reliability: Cronbach alpha ranged from 0.856 to 0.886, and the composite reliability ranged from 0.883 and 0.895.

Table 4 Factor analysis

| Soft skills gaps | Factor loading | Cronbach alpha | Composite reliability | Variance extracted |

| Personal skills | 0.886 | 0.895 | 22.327% | |

| Problem solving | 0.635 | |||

| Initiative and commitment | 0.697 | |||

| Customer orientation | 0.689 | |||

| Ethical conduct and respect | 0.647 | |||

| Willingness to change | 0.701 | |||

| Promoting a positive work environment | 0.718 | |||

| Creativity | 0.709 | |||

| Willingness to learn and to perform | 0.719 | |||

| Communication and cultural skills | 0.878 | 0.883 | 20.021% | |

| Written communication skills | 0.761 | |||

| Oral communication skills | 0.763 | |||

| Active listening skills | 0.711 | |||

| Skills related to cultural awareness and expression | 0.724 | |||

| Skills related to awareness of local customs (e.g., food, arts, language, crafts) | 0.670 | |||

| Ability to speak foreign languages | 0.557 | |||

| Skills related to intercultural host-guest understanding and respect | 0.621 | |||

| Diversity skills | 0.856 | 0.891 | 16.691% | |

| Gender equality skills | 0.742 | |||

| Age-related accessibility skills | 0.779 | |||

| Diets and allergy needs skills | 0.704 | |||

| Skills related to disabilities and appropriate infrastructure | 0.754 | |||

| Skills related to diversity in religious beliefs | 0.748 |

Note: Total variance explained=59.039%; KMO Measure of Sampling Adequacy=0.942; Bartlett’s test of sphericity: χ2=14267.122, df=190, p=0.000; Extraction: Principal components based on eigenvalues (= 1) and Varimax rotation

4.4 Cluster analysis

Two-step cluster analysis revealed the existence of two groups of respondents based on their social skills gaps. K-means cluster analysis was used for classification of individual respondents into the two clusters (distance between the cluster centres=3.842). The results are presented in Tables 5 and 6. Cluster 1 (n=871) respondents reported very small but positive social skills gaps (min=0.04, max=0.42) while Cluster 2 (n=533) respondents identified high social skills gaps (min=0.75, max=1.29). The differences in the responses of the two cluster members were all significant at p<0.001 (Table 6). The composition of the two clusters was quite different. For example, over two thirds of respondents from Italy, Hungary, and the Netherlands belonged to Cluster 1, respondents from Germany and Bulgaria were more evenly distributed, while most Irish respondents were classified in Cluster 2 (χ2=29.969, df=8, p=0.000). Similarly, two thirds of accommodation establishments, visitor attractions, and tour operators and travel agents were in Cluster 1 while only around 55% of DMOs and F&B outlets (χ2=12.370, df=4, p=0.015). Finally, 80% of individual/part-time activity respondents and 68.06% of micro-organisations were classified in Cluster 1, around 55% of medium and small organisations were in that cluster, while large organisations were nearly equally split (χ2=43.750, df=4, p=0.000).

Table 5 Cluster analysis - clusters’ characteristics

| Characteristic | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Chi-square |

| Country | χ2=29.969 (df=8, p=0.000) | ||

| Italy | 257 | 113 | |

| Germany | 140 | 106 | |

| UK | 143 | 90 | |

| Spain | 85 | 54 | |

| Bulgaria | 75 | 60 | |

| Hungary | 88 | 35 | |

| Ireland | 34 | 40 | |

| Netherlands | 27 | 13 | |

| Other | 22 | 22 | |

| Sector | χ2=12.370 (df=4, p=0.015) | ||

| Accommodation | 339 | 186 | |

| Destination management | 162 | 133 | |

| Visitor attractions | 141 | 71 | |

| Food & beverage | 116 | 85 | |

| Travel agents and tour operators | 113 | 58 | |

| Size | χ2=43.750 (df=4, p=0.000) | ||

| Large (250 or more employees) | 65 | 63 | |

| Medium (100-249 employees) | 71 | 57 | |

| Small (10-99 employees) | 286 | 226 | |

| Micro (Less than 10 employees) | 341 | 160 | |

| Individual or part-time activity | 108 | 27 | |

| Total | 871 | 533 |

Notes: N=1404; Level of significance: ***p<0.001; * p<0.01; *p<0.05

Table 6 Cluster analysis - differences among clusters to the soft skills gaps

| Soft skills | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | t-test | ||

| Mean | Standard deviation | Mean | Standard deviation | ||

| Personal skills | |||||

| Problem solving | 0.20 | 0.636 | 0.87 | 0.721 | -17.658*** |

| Initiative and commitment | 0.10 | 0.636 | 0.86 | 0.770 | -18.790*** |

| Customer orientation | 0.10 | 0.632 | 0.78 | 0.766 | -17.414*** |

| Ethical conduct and respect | 0.04 | 0.587 | 0.75 | 0.742 | -18.816*** |

| Willingness to change | 0.23 | 0.698 | 1.18 | 0.911 | -20.680*** |

| Promoting a positive work environment | 0.14 | 0.641 | 0.99 | 0.798 | -20.927*** |

| Creativity | 0.17 | 0.649 | 1.04 | 0.861 | -20.126*** |

| Willingness to learn and to perform | 0.11 | 0.619 | 0.95 | 0.811 | -20.602*** |

| Communication and cultural skills | |||||

| Written communication skills | 0.11 | 0.686 | 0.90 | 0.734 | -19.932*** |

| Oral communication skills | 0.07 | 0.663 | 0.91 | 0.734 | -21.615*** |

| Active listening skills | 0.16 | 0.700 | 1.14 | 0.765 | -24.101*** |

| Skills related to cultural awareness and expression | 0.26 | 0.723 | 1.27 | 0.743 | -25.066*** |

| Skills related to awareness of local customs (e.g., food, arts, language, crafts) | 0.12 | 0.670 | 1.01 | 0.773 | -22.013*** |

| Ability to speak foreign languages | 0.42 | 0.823 | 1.29 | 0.696 | -17.315*** |

| Skills related to intercultural host-guest understanding and respect | 0.18 | 0.688 | 1.17 | 0.789 | -23.849*** |

| Diversity skills | |||||

| Gender equality skills | 0.13 | 0.659 | 0.90 | 0.882 | -17.607*** |

| Age-related accessibility skills | 0.17 | 0.660 | 1.08 | 0.873 | -20.639*** |

| Diets and allergy needs skills | 0.26 | 0.710 | 1.08 | 0.839 | -18.745*** |

| Skills related to disabilities and appropriate infrastructure | 0.34 | 0.805 | 1.27 | 0.925 | -19.223*** |

| Skills related to diversity in religious beliefs | 0.27 | 0.679 | 1.19 | 0.946 | -19.626*** |

Notes: N=1404; Level of significance: ***p<0.001; * p<0.01; *p<0.05

4.5 Social skills training

Table 7 presents the results on the social skills training provided by tourism and hospitality companies. More than half of respondents (740, or 52.71%) reported social skills training provided to the employees in their organisations.

Table 7 Soft skills training provided by tourism and hospitality companies

| Characteristic | No training provided | Training provided | Chi-square | |||||||||

| Total | On the job training | Online course | One-day on-site training by external provider | Several days on-site training by external provider | One day off-site training by external provider | Several days off-site training by external provider | Apprenticeship | Vocational training | Higher education | |||

| Country | ||||||||||||

| UK | 127 | 106 | 87 | 44 | 37 | 14 | 19 | 12 | 17 | 16 | 9 | χ2=307.251, df=64, p=0.000 |

| Italy | 214 | 156 | 123 | 20 | 11 | 13 | 12 | 9 | 6 | 20 | 7 | |

| Ireland | 21 | 53 | 47 | 8 | 18 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 8 | |

| Spain | 62 | 77 | 48 | 34 | 24 | 14 | 11 | 13 | 5 | 2 | 4 | |

| Hungary | 70 | 53 | 32 | 9 | 20 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 15 | 7 | 4 | |

| Germany | 77 | 169 | 68 | 49 | 50 | 29 | 104 | 42 | 24 | 17 | 11 | |

| Netherlands | 14 | 26 | 18 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 6 | |

| Bulgaria | 61 | 74 | 59 | 12 | 14 | 11 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 5 | |

| Other | 18 | 26 | 18 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 2 | |

| Sector | ||||||||||||

| Destination management | 109 | 186 | 93 | 49 | 60 | 34 | 80 | 41 | 26 | 20 | 10 | χ2=112.567, df=32, p=0.000 |

| Food & beverage | 103 | 98 | 77 | 15 | 19 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 17 | 13 | 12 | |

| Visitor attractions | 90 | 122 | 80 | 31 | 37 | 12 | 20 | 9 | 8 | 11 | 11 | |

| Travel agents and tour operators | 98 | 73 | 48 | 29 | 15 | 14 | 18 | 16 | 9 | 9 | 7 | |

| Accommodation | 264 | 261 | 202 | 67 | 58 | 34 | 46 | 21 | 29 | 27 | 16 | |

| Size | ||||||||||||

| Large (250 or more employees) | 39 | 89 | 61 | 35 | 40 | 25 | 18 | 16 | 14 | 15 | 12 | χ2=72.916, df=32, p=0.000 |

| Medium (100-249 employees) | 45 | 83 | 47 | 35 | 30 | 17 | 17 | 15 | 17 | 7 | 13 | |

| Small (10-99 employees) | 219 | 293 | 197 | 67 | 80 | 35 | 67 | 40 | 37 | 31 | 20 | |

| Micro (Less than 10 employees) | 266 | 235 | 165 | 48 | 35 | 23 | 58 | 21 | 19 | 25 | 10 | |

| Individual or part-time activity | 95 | 40 | 30 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Total | 664 | 740 | 500 | 191 | 189 | 102 | 171 | 94 | 89 | 80 | 56 | |

Note: N=1404.

On the job training was by far the most popular training provided by the organisations of 500 of the respondents, followed by online courses (n=191), one-day on-site training by external provider (n=189), and one-day off-site training by external provider (n=171). Payment for a higher education degree related to social skills was least provided (n=56). There were significant differences based on the country of registration of the organisation, its sector and size. In terms of country, German respondents reported most training in the form of one-day off-site training by external provider, while British, Italian, Irish and Bulgarian respondents had mostly on the job training, and the differences were statistically significant (χ2=307.251, df=64, p=0.000). Unsurprisingly, local-bound service providers such as accommodation establishments, F&B outlets, and visitor attractions focused more on the job training, while DMOs relied on one-day off-site training by external provider as well because practically their employees need to be familiar with the tourist offer of the destination they manage (χ2=112.567, df=32, p=0.000). Logically, due to their size that drives the need for social skills training and the availability of financial resources, 69.5% of large organisations provided social skills training to their employees, while only 46.9% of micro-organisations did so. Moreover, large, and medium sized organisations had a greater diversity in the types of training they provided compared to the smaller organisations (χ2=72.916, df=32, p=0.000).

5. Discussion and Implications

The empirical data provides clear evidence of the importance of all three categories of social skills including personal skills; cultural and communication skills and diversity skills. This strongly supports the often-missed correlation between inter-personal skills such as listening, empathy, care and respect for others and sustainable tourism criteria. This includes a greater understanding and practice of gender equality in the workplace, enhanced cross-cultural understanding for customers and employees, greater recognition of cultural, religious, and dietary preferences that promotes respect, care and equality for all customers and employees. The research provides evidence of skills gaps in tourism organisations in 2019 that continue to the present day and beyond, and which urgently need to be addressed to support future just, fair and sustainable societies. Consistently with previous research (Balcar, 2016; Sisson & Adams, 2013) this study also shows the importance of soft skills in the tourism industry. Sisson & Adams (2013) identified 33 skills, competencies, and abilities applicable across the areas of lodging, food and beverage and meetings and events. Managers of the different functional areas were then surveyed, and the findings revealed that “the most essential competencies for hospitality graduates to possess are in the soft category” (p.143) and they concluded that educational “programs should stress teaching hospitality students’ soft competencies in favour of hard competencies” (p.131). These soft skills present unique opportunities to capture inter-personal, communication and diversity skills to enhance sustainable tourism indicators (Baum 2018) and hospitality practices that can help provide the missing link to achieve “socially sustainable tourism” (Devile et al., 2023; Habimana et al., 2023; Mínguez et al., 2021).

The research demonstrated significant gaps between current skills of employees and future skills required by businesses and destination management organizations, a factor which concurs with Baum (2018) who calls for sustainable human resource management practices and greater recognition of the value of the tourism workforce to support sustainability practices. In particular, skills such as languages for tourism service provision, awareness and understanding of people with disabilities, accessibility requirements and increased implementation of gender equality strategies for employees and customers are no longer considered unimportant or irrelevant and instead an essential part of many roles and responsibilities of service personnel and senior managers. However, as the gaps are less significant in customer orientation and ethical conduct it implies that respondents were more confident in these areas of service provision as opposed to other skills which require significant levels of knowledge and understanding to deliver service in second and third languages and provide greater compassion and empathy for those with accessibility or disability requirements. These latter skills provide opportunities for new markets of tourists that perhaps have not been considered before. Respondents reported the highest proficiency levels in customer orientation and ethical conduct which also indicates that a correlation between excellent customer service for all customers is essential despite a tourists’ country of origin, culture, religion, or language. Such company ethos encourages employees to navigate the social fabric of a destination society and seek local and foreign identities, novelty, learning opportunities and self-development. This in turn can help place value on ethics, morality, social harmony and emotional well-being of self and others as a core component of employees and indeed may encourage tourists to be more mindful and friendly towards other tourists whilst on holiday. To respond to these demands the workforce needs to develop awareness of a range of social factors surveyed in this research that can influence the tourist experience including listening skills, problem solving, communication and leadership.

Hospitality and tourism industry competitiveness is largely determined by service quality competencies (Park & Jeong, 2019), however tourists in a globalised world depend highly on technology and are increasingly self-sufficient in the way they organise travel, personalising and seeking meaningful, genuine, culturally respectful, and environmentally sound experiences. This means that increasingly employees require knowledge and understanding of “cultural differences in religions, customs, work ethics, languages, and behavioural codes and standards” (Reseinger, 2009, p. 25); managing difficult situations with empathy and creativity; communicating effectively with people from different backgrounds, ages, and cultures; recognizing and responding against discriminatory practices and understanding the value placed by travellers on safety, security, social stability, and human rights. The term “transversal skills” highlights the broad applicability of social skill sets which can transcend job role hierarchies; be applied to different sectors and be societally relevant (Tilea & Duta, 2015).

Although stronger cognitive skills are solid indicators of success among high income positions, in the lowest earning levels of employment, social and emotional skills are 2.5 to 4 times more important than cognitive ability helping low level earners to access the workforce and retain their jobs (Chernyshenko et al., 2018). While necessary on all types of industries, social skills are particularly important on non-manual jobs. Tourism and hospitality, as a service industry with predominantly low entry barriers, intense communication, and intercultural relations, casts a strong emphasis on the capacity to deal with emotions and interact constantly with different people, what Hochschild (1983) has termed “emotional labour”.

Given the key focus of this skills gaps research, “skill (mis-) alignment between academic push, industry pull, and educational offerings” (Börner et al., 2018, p. 12630) is a dilemma that is increasingly challenging policymakers, government organisations, training institutions and businesses. Often employers find that workers and students are not well enough prepared to deal with the pressures of a changing and demanding sector (Hurrell, 2016,) where “employer interviews identified skills gaps and persistent recruitment difficulties with responses including downsizing, deskilling and overseas recruitment as key barriers” (Haven‐Tang & Jones, 2008, p.353). Even tourism students recognisze a low level of preparedness for unexpected crisis situations (Mínguez et al. 2021).

The results illustrate a wide range of variations between countries and the self-perceived reality of skills gaps is based on the culture of their organisation of which the senior managers are part and the cultural and personal attitudes towards certain social and soft skill sets (Magalhães et al., 2023). Additionally, the results demonstrate how perceptions of social skills could potentially lead to discrimination or prejudice particularly towards tourists or employees with disabilities or a different religious or cultural orientation (Zhou et al. 2022). Therefore, the results demonstrate a relationship between the skills the senior managers think that their employees have and the skills they think their employees should have.

Cluster analysis shows that Irish managers believe that their employees present more social skills gaps, particularly in less well-known skill sets supporting disability awareness and use of languages and have higher demands and expectations for skills in the future. This can also be interpreted that Irish tourism and hospitality businesses demanding higher levels of social skill sets for their current employees and have higher expectations of customer service levels, while Hungarian or Italians are more content with the current skills and less concerned about the future of social skills. The results also demonstrate how large companies (250+ employees) have higher expectations of what skills are important and required in the future, whilst individuals and micro-organisations are more content and confident with the current skills and future skills required thus demonstrating a lower skills gap. The perception of these skill gaps can be culturally informed and allow for a great deal of subjectivity that could be further researched to explore why these attitudes about skills exist for different countries (Magalhães et al., 2023).

An over emphasis on social skills could entail other risks for employee wellbeing. Although often “the industry has a strong preference to hire people with “soft” people management skills” (Marneros et al., 2020, p. 237), as mentioned, social skills are very difficult to assess and therefore, quite often, the selection process is strongly based on the perceptions (and prejudices) of the recruitment team leading to conscious or unconscious pretexts for discrimination. In a systematic review of research published between 1985 to 2020, Zhou et al. (2022, p. 1037) found that “the main sources of discrimination in hospitality and tourism services include sexism, racism, ethnocentrism, lookism and ego-altruism”. Gender stereotypes about the innate qualities of each sex (Bakas et al., 2018; Costa et al., 2017), assumptions regarding ethnic identity and capacity, “lookism” or the discrimination based on appearance or the recognition of self-characteristics as preferable for the position are some of the ways in which soft skills, identities and employment categories can intersect, leading to discriminatory practices in the recruitment, recognition of pay levels and career progression (Bailly & Léné, 2013; Macdonald & Merrill, 2009).

Often “‘soft-skills’ are not recognized as skills at all, but rather part of the natural order of things” (Burns, 1997, p. 241) allowing hospitality management to keep low wages based on the idea of “unskilled labour”, which arguably diminishes the value of social skills development. Considering the above discussion, the research predominantly indicates the importance of training and education for social skills to overcome the issues highlighted above and to support the tourism and hospitality industry as an integral part of society and for the purpose of managing a successful and competitive business operation as well as fulfilling European policy agendas. However, future training initiatives must be culturally situated in the local, regional, and national contexts to reflect the nuanced attitudes and culturally specific perspectives that may prevail in a country. This implies a need to direct training initiatives that respond to European policy agendas that support equality and diversity of employees and tourists and training that supports a greater understanding of culturally sensitive topics for the tourism and hospitality industry.

The identified skill sets alongside the NTG training resources produced during the lifespan of the NTG Alliance project also provide a comprehensive guide to training in the core skills identified. Although it is recognised that the research is not an exclusive list of skills per se, social skills gaps can be categorised and grouped as the research demonstrates which provides a significant focus to businesses who wish to progress and close social skills gaps. Most companies prefer in-house training, followed by online options that can be completed independently. The research shows that there is not much investment in degree apprenticeships whilst employees are in work, however, locally bound service businesses have more in-house training while DMOs do more outside training where external training providers are used for professional courses.

5. Conclusion

The research demonstrates significant gaps in social skills that could better support the managerial and operational response to the urgent changes facing the tourism and hospitality industry post Covid-19 that correlate with the new European Skills Agenda. The Pact for Skills Strategy (European Commission, 2020a) calls for investment in new opportunities to enhance knowledge and skills to sustain and widen customer markets and contribute to the twin transition to a digital and green economy through leadership, problem-solving and communication skills, which is urgently needed to achieve effective environmental management systems (EMS) and manage climate change through resilience and pro-active innovation. Customers also need to experience high levels of quality service to reassure customers returning following the Covid-19 pandemic and increase the rate of attraction of employees who left the sector to work elsewhere (Enback, 2020; European Commission, 2020a). Therefore, key social skills supporting an understanding of the cross-cultural diversity of residents, employees, and tourists; gender equality amongst workers; accessibility and disability and religious preferences, are needed to embrace the high levels of mobility and diversity across countries that the tourism industry relies on (Chrobot-Mason and Leslie 2012). Soft skills including personal, interpersonal communication skills are highly significant in the management of social relations between managers, employees, and tourists, particularly in times of staff shortages. To increase effective practice of the social skills required in these core areas of tourism, the appropriate human resource, operational structures, and effective training to enable the necessary decisions and actions to support business opportunities and better human relations in society.

As previously explained the EU has invested in the creation of the “Blueprint for Sectoral Cooperation on Skills” (European Commission, 2017) and Pact for Skills (European Commission, 2021) which fosters sustainable partnerships among stakeholders to translate tourism growth into a comprehensive skills strategy to close skills gaps. A skills-based pathway targeted at different levels of roles and responsibilities can help people to progress in their careers in tourism and develop transversal skills that can in turn support more responsible business practices for the well-being of employees and customers. This in turn could help improve the poor image associated with tourism employment.

There are several limitations of this study including the need for additional skill sets to be added to the list of social skill sets including for example resilience and crisis management. The date of the survey study was pre-Covid and therefore needs updating as employees return to the industry. This is a key aim of the next phase of the NTG Alliance via the European Commission funded PANTOUR project. As the research was primarily with senior managers the scope of research could also be expanded to include all levels of employees to encourage greater personal reflection on social skills gaps. Social skills and their role in sustainable tourism policy implementation requires greater more attention. Future research directions also include the effectiveness of in-house social skills training and development of good practice, as well as how to encourage social skills within curricula and training programmes. The impacts of digital technologies and Artificial Intelligence on the importance of social skills also needs further exploration.

The social skills element of sustainable tourism has received scant recognition in the literature and provides a rich area for future research to further exploration of the correlation between implementation of sustainable tourism and the social skills to achieve key actions and practices. In addition, there is the opportunity to develop evidence and research of the importance of combined social, green, and digital skill sets to achieve sustainable tourism and hospitality practices such as how tourism information is made accessible for people with disabilities or how digital programmes can support environmental data collection, auditing and monitoring of environmental impacts. Finally, there is a need to consider the perceptions of employees of their own skill sets and how they may improve social skill sets according to different roles and hierarchies of positions in companies.

Acknowledgment

This publication is developed within the frame the “Next Tourism Generation Alliance" (NTG Alliance) project of the European Commission (project reference 17D029897). This project has been funded within the Erasmus+ KA2 programme (Sector Skills Alliances 2018 for implementing a new strategic approach (Blueprint) to sectoral cooperation on skills; EAC/A05/2017, LOT 3) and with support from the European Commission. This publication only reflects the views of the authors, and the European Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.