Introduction

Financial statements are a relevant resource for stakeholders to evaluate the performance of companies. The main output of financial statements is accounting earnings, which are important to assess a firm’s economic performance (Burgstahler, Hail & Leuz, 2006). However, accounting earnings can be managed because managers have privileged access to information and earnings are subject to a set of estimates and professional judgments. Earnings management (EM) can be defined as a strategy used by managers to influence a firm’s underlying economic situation (Walker, 2013) towards specific targets, namely accounting and financial benchmarks (i.e., earnings benchmarks (EB); (Burgstahler & Dichev, 1997)). Moreover, engagement in EM practices implies severe problems regarding earnings quality (EQ), which compromises the correct reading of the financial data reporting (Dechow, Ge & Schrand, 2010).

As highlighted by Ruiz (2016), the EM topic has been widely investigated in business research. In this field, the literature has explored several aspects, ranging from EM incentives and determinants (Bergstresser & Philippon, 2006; Enomoto, Kimura & Yamaguchi, 2015) to alternative EM practices (Gunny, 2010; Roychowdhury, 2006; Zang, 2012). Other topics include the particular case of EM in family businesses (Borralho, Gallardo-Vázquez & Hernández-Linares, 2020; Kvaal, Langli & Abdolmohammadi, 2012) and in bankrupt firms (Rosner, 2003).

EM seems to be industry-dependent (Beatty, Ke & Petroni, 2002; Dimitropoulos, 2011; Leone & Van Horn, 2005; Martinez & Carvalho, 2022), with the hospitality sector offering an interesting setting to explore this issue. This industry frequently operates under management contracts (Turner & Guilding, 2011; Xiao et al., 2012), presents a high proportion of tangible assets and high fixed costs (Chen, 2010; Turner & Guilding, 2011), has high debt-to-equity ratios and financial risk (Li & Singal, 2019; Singal, 2015; Tang & Jang, 2007) and makes significant expenditures on human resources (Jiao & Lu, 2019; Shin & Hong, 2020). Seasonality, cyclicity and high competitiveness (Chen, 2010; Jiao & Lu, 2019; Poretti, Schatt & Jérôme, 2020; Yeh, 2019) are also critical characteristics of this industry. Importantly, the travel and hospitality sector has globally experienced very high growth rates over the last decade, attracting significant levels of domestic and foreign investment (WTTC, 2021a). Yet the last years were very problematic for the industry, which was significantly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic crisis (UNWTO, 2021; WTTC, 2021b).

Notwithstanding the previous points, there is little research on the EM practices of hospitality firms. The limited empirical evidence that exists (Parte-Esteban & Ferrer García, 2014; Parte-Esteban & Alberca-Oliver, 2016; Sousa Paiva & Lourenço, 2016; Poretti et al., 2020) suggests that such practices are influenced by the intrinsic characteristics of companies (e.g., size, growth opportunities and leverage), country factors (e.g., legal systems and the level of investor protection) and macroeconomic and regional factors (e.g., occupancy rates and the number of arrivals and visitors staying overnight). In addition, there is preliminary evidence to suggest that, in this sector, the EM practices may differ across industry segments (e.g., hotel chains vs independent hotels and hotels vs restaurants). So, what do we really know about the EM behaviour of hospitality firms? This study develops a systematic literature review (SLR) to address this important question. The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the methodology. Section 3 reports the findings, and Section 4 concludes.

2. Methods

2.1 Research design

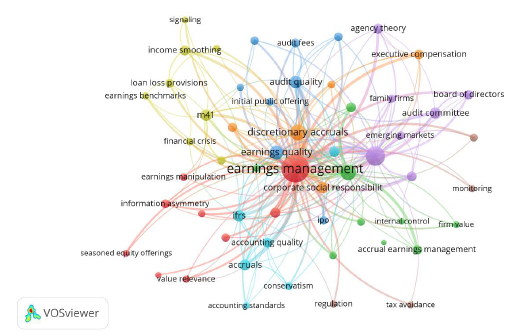

This investigation is a systematic review focused on the EM practices of the hospitality industry. It is implemented in four steps, as described by Tranfield, Denyer and Smart (2003) and Denyer and Tranfield (2009). The first is a scoping study, which is an ad hoc review of the existing literature on EM (3.500 articles searched in December 2022 on Web of Science - Core collection). This was done via bibliometric network analysis that maps various links in the literature, including the co-occurrence of the authors’ keywords. As can be seen in Figure 1, this procedure identified one main keyword, ‘earnings management’. Another keyword that stood out in our analysis is ‘earnings quality’.

Given the focus of this study, the analysis is restricted to the hotel sector, represented by the keywords ‘hotel industry’, ‘hospitality industry’, ‘lodging sector’, ‘lodging industry’, ‘accommodation sector’ and hotel*.

In the second step of the SLR, the main keywords were combined into search strings as follows:

‘earnings management’ AND (‘hotel industry’ OR ‘hospitality industry’ OR ‘lodging sector’ OR ‘lodging industry’ OR ‘accommodation sector’ OR hotel*);

‘earnings quality’ AND (‘hotel industry’ OR ‘hospitality industry’ OR ‘lodging sector’ OR ‘lodging industry’ OR ‘accommodation sector’ OR hotel*);

The first search string combines the keyword ‘earnings management’, which is the focus of this study, with alternative expressions related to the hospitality industry. The second search string combines the keyword ‘earnings quality’, which resulted from the bibliometric analysis, with keywords for the hospitality industry. These two search strings were used in the most popular databases in the social sciences and tourism areas: EBSCO host, Web of Science and SCOPUS. For completeness, the search strings were also used in the Emerald, Science Direct (Elsevier), Taylor & Francis, Sage and Wiley databases, since these publishers host most of the journals present in the SCImago Journal & Country Rank (SJR) in the Tourism, Leisure and Hospitality Management category. All searches were made in December 2022, and they focussed on the abstract, title and subject terms (keywords plus in Web of Science or Indexterms in Scopus) as well as author keywords when available.

After removing duplicates, step 3 of the SLR excluded articles published in sources other than scientific journals, articles published in languages other than English or studies that do not focus on earnings management or earnings quality within the hospitality industry. The remaining articles were read in full in step 4 to ascertain their eligibility for inclusion in the final sample depending on whether they clearly present the research questions with proper literature support, describe the sample and methodology applied, appropriately discuss the results and contribute to the existing knowledge on EM in the hospitality industry. In the end, only the papers that were in compliance with both the inclusion and exclusion criteria were considered in this review.

2.2 Outcome of the selection process

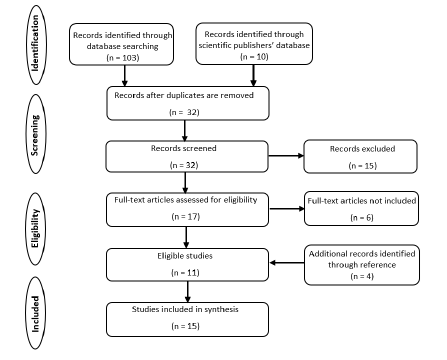

The selection process implemented in this study is summarised in Figure 2. We followed, with minor adjustments to fit the study’s purpose, the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff & Altman, 2009), a tool used to conduct the review protocol and to improve the reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

A total of 113 articles were identified, with 81 duplicates. Fifteen papers were deleted as per the exclusion criteria (seven records were not academic articles, three records were not written in English, and five records were not related to our main topic). After applying the inclusion criteria abovementioned, this study found 11 articles that were suitable for the review, while six articles were not included (three articles did not contribute to the existing knowledge on EM in the hospitality industry, and another three did not appropriately discuss their results). After cross-referencing these 11 studies, four additional papers were identified. Hence, a total of 15 articles were included in the final review.

3. Findings

3.1 Evolution of publications on EM in the hospitality industry

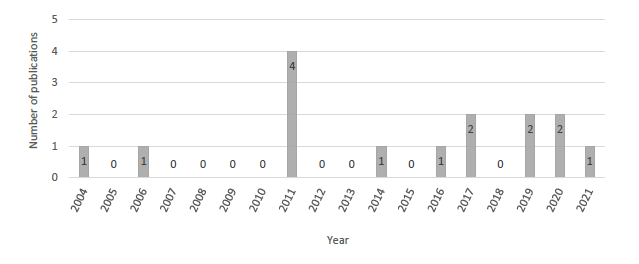

The final sample includes articles published from 2004 to 2021. Figure 3 shows their annual distribution. While the term ‘earnings management’ has been widely researched since the late 1980s (Ruiz, 2016), the first publication pertaining to the hospitality industry dates from 2004. Furthermore, an increasing interest in this topic was observed from 2011 onward, with about 87% of the articles published between 2011 and 2021 (13 out of 15).

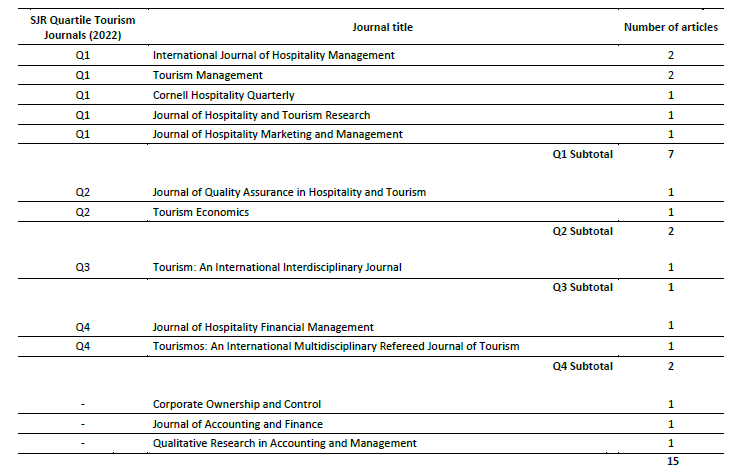

The studies included in the final sample were distributed across 13 journals. As can be seen in Table 1, most of these journals were indexed in the Tourism, Leisure and Hospitality Management category in the SCImago Journal & Country Rank (SJR).

Table 1 Distribution of articles by journal title and SCImago Journal & Country Rank

Source: Own elaboration

The distribution of scientific articles per journal is relatively homogeneous, ranging from one to two. Most studies included in this review were published in top tourism journals, which are in the first SJR quartile.

3.2 Empirical evidence of earnings management practices in the hospitality industry

This section examines the fifteen articles included in the final sample. Following Bisogno and Donatella (2021), we used an analytical framework to categorise and analyse the findings of these papers, which are organised around five different categories as presented in Table 2.

3.2.1 Continent of research

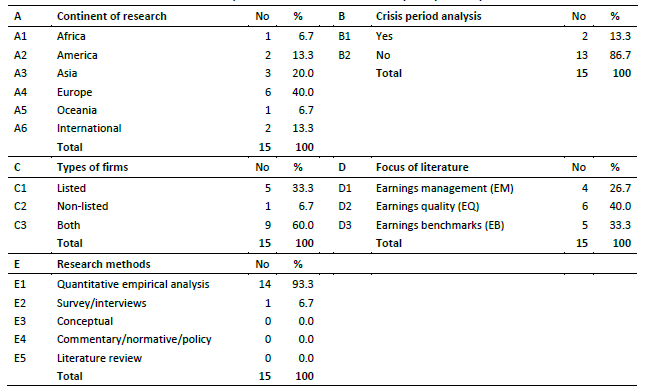

The distribution of publications per continent of research indicates that Africa and Oceania are the least studied continents, with only one article each. The American continent is considered in two studies, and there are three studies that use Asian samples. Europe is the most investigated continent, with six articles. The higher incidence of research using European samples is likely due to the importance of tourism on this continent. In 2019, Europe was the world’s most important destination, with international arrivals reaching 742 million, which represented 51% of the world’s total arrivals (UNWTO, 2020b). Five of the articles focusing on Europe (Parte-Esteban, Devesa & Alberca- Oliver, 2011; Parte-Esteban & Alberca-Oliver, 2016; Parte-Esteban & Devesa, 2011a, 2011b; Parte-Esteban & Ferrer García, 2014), consider the particular case of the Spanish hotel industry. Costa and Mota (2021) focus on the hotel industry in Portugal, which is also an Iberian country. The Asian studies are concentrated around the Korean case. In effect, the country’s economic crises led to the bankruptcy of several hotel companies in 1997 (Jeon, Kang & Lee, 2004; Jeon, Kim & Lee, 2006), which later allowed the expansion of this sector (Shin & Hong, 2020). Studies in the American context, more specifically, in the United States (Gim, Choi & Jang, 2019; Jiao & Lu, 2019), are motivated by the country’s relevance in global tourism, its position as the number one country for international tourism receipts (UNWTO, 2019) and the availability of financial information (Parte-Esteban & Devesa, 2011a). Seetah (2017) is the only study that considers an African country, namely Mauritius. The hospitality industry is one of the main economic activities on the island, significantly contributing to its GDP and employment and attracting investment to the region. Australia and New Zealand, the two most representative countries in terms of Oceania’s tourism indicators (UNWTO, 2020a), do not receive much attention in this literature, being analysed only in Turner and Guilding’s (2011) study.

3.2.2 Crisis Period Analysis

Financial crises influence the discretionary accounting behaviour of managers (Conrad, Cornell & Landsman, 2002; Kousenidis, Ladas & Negakis, 2013; Strobl, 2013; Trombetta & Imperatore, 2014). This also seems to be the case within the hospitality industry. As Table 2 shows (category B), two articles (about 15% of the total papers under review) explicitly account for this variable and study its impact on the EM practices of the hotel industry (Parte-Esteban & García, 2014; Seetah, 2017). Both studies show that financial crises negatively affected earnings quality in the hospitality industry, implying that earnings manipulation is higher during such periods.

3.2.3 Types of firms

Companies can be publicly traded or privately held. Publicly-traded firms are registered on recognised stock exchanges, which allows external financing (Burgstahler et al., 2006). The number of shareholders is almost unlimited, and their identities often change through stock market trading (Ball & Shivakumar, 2005). In contrast, privately held firms predominantly resort to bank financing and tend to be more closely held (Ball & Shivakumar, 2005). Listed firms have higher ownership dispersion and usually separate ownership and control. This leads to increased information asymmetry and higher agency costs (Campa, 2019; Hope, Langli & Thomas, 2012). These differences explain the reason the extant literature on EM presents distinct motivations, determinants and consequences for listed and unlisted firms (Coppens & Peek, 2005; Burgstahler et al.; Campa, 2019). This is also important in the context of the hospitality industry. As can be seen in Table 2 (category C), five of the articles focus solely on listed firms (Sousa Paiva & Lourenço, 2016; Seetah, 2017; Gim et al., 2019; Jiao & Lu, 2019; Poretti et al., 2020). In contrast, only one of the articles looks exclusively at non-listed companies (Parte-Esteban & Alberca-Oliver, 2016). The remaining nine studies use mixed samples (Costa & Mota, 2021; Jeon et al., 2004, 2006; Parte-Esteban et al., 2011; Parte- Esteban & Devesa, 2011a, 2011b; Parte-Esteban & García, 2014; Shin & Hong, 2020; Turner & Guilding, 2011).

Overall, there is clear evidence suggesting that hospitality managers tend to manage their earnings figures regardless of the type of company. Both publicly and privately held firms have specific incentives to engage in EM practices, with listed firms influenced by agency costs, asymmetric information and the market’s response to the firms’ financial information. On the other hand, unlisted firms tend to be affected by the debt covenants hypothesis, political visibility and managers’ bonus plans (Parte-Esteban & Devesa, 2011b; Watts & Zimmerman, 1986).

Focus of the literature

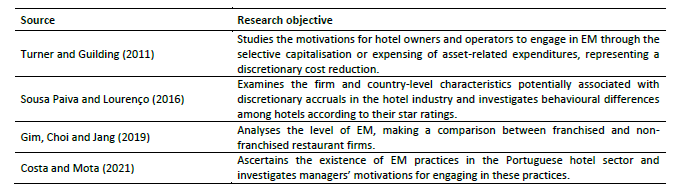

The literature on earnings manipulation within the hospitality industry considers three different perspectives (see Table 2 - category D): EM techniques (four articles), EQ (six articles) and EB (five articles). The EM perspective is covered by four articles following distinct objectives, as summarised in Table 3.

Turner and Guilding (2011) focus on discretionary cost reduction (i.e., real activities manipulation) through capitalisation of asset- related expenditures and present incentive management fees, which are commonly based on a percentage of a hotel’s gross operating profit, as the main motivation for hotel owners and, especially, operators to engage in these EM practices. Sousa Paiva and Lourenço (2016) find that a country’s legal system and some firm-level determinants, such as the leverage ratio, investment opportunities, cash flow from operations and frequency of negative earnings, are the most relevant determinants of the level of EM in the hospitality industry, although their impact on EM may depend on the hotels’ star rating. Gim et al. (2019) look at the behavioural differences between franchise and non-franchise restaurant firms and report that the former engage more actively in EM than the latter, especially when facing more growth opportunities and a greater need for additional capital. Finally, Costa and Mota (2021) show that Portuguese hotels use EM practices to achieve certain financial goals and find that the debt level and firm size are the main determinants of such behaviour.

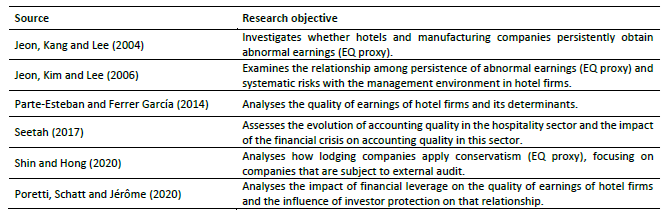

Dechow et al. (2010) highlight that EM practices reduce earnings quality. As such, the higher the quality of the information reflected in the earnings component, the lower the risk that those earnings have been managed. Research on EQ resorts to different proxies, as presented in the six articles identified in Table 4.

Jeon et al. (2004) report that hotel earnings, particularly for first- and middle-class hotels, are more stable than in manufacturing companies, presenting higher quality and, thus, lower earnings manipulation. Jeon et al. (2006) focus exclusively on hotel firms and find that systematic risk used as a proxy for hotel profitability is negatively correlated with the persistence of abnormal earnings, which increase with the exchange rate and the existence of hotel chains. Conversely, Parte-Esteban and Ferrer García (2014) show that financial crisis, internationalisation, location, ownership structure and audit function influence hotels’ earnings quality. Seetah (2017) found a negative impact of the financial crisis on accounting quality, suggesting that these critical periods potentiate EM practices and reduce the quality of earnings. In line with the results of Jeon et al. (2004), Shin and Hong (2020) report that lodging companies present higher earnings quality than manufacturing companies since they are more conservative in accounting practices. Poretti et al. (2020) find that financial leverage is negatively (positively) related to EM (EQ), although these results depend on the institutional context.

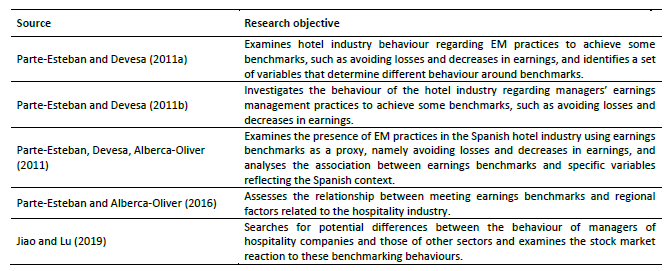

A third strand of the literature explores how the pressure to meet/beat certain accounting and financial benchmarks affects the EM practices of hotel managers. This perspective is adopted by the five articles presented in Table 5.

All studies presented in Table 5 find a discontinuity near the zero earnings’ level, which is evidence of EM to avoid reporting losses or a decrease in earnings. Furthermore, Parte-Esteban and Devesa (2011a) show that just-beating and just-missing firms report differences in their sales, operating expenses, gross margin, depreciation, other expenses, interest, taxes, extraordinary income, current ratio liquidity, growth and leverage. Parte-Esteban and Devesa (2011b) find that hospitality managers are more concerned about avoiding losses than decreasing earnings, and Parte-Esteban et al. (2011) add that non-audited and highly leveraged firms engage more in EM. In addition, Parte-Esteban and Alberca-Oliver (2016) find a negative relationship between meeting earnings benchmarks and regional tourist flow since those firms can only achieve their financial targets with EM. In comparing restaurants and hotels, Jiao and Lu (2019) report that restaurants seem to achieve earnings benchmarks through real EM methods, while hotels rely more on accruals EM.

Importantly, as Bisogno and Donatella (2021) and Manes-Rossi, Nicoló and Argento (2020) emphasise, a research field is typically not mature if most of the empirical work is done without drawing on existing theory. This clearly seems to be the case of the studies that focus on the hospitality industry, as most of the articles reviewed in this paper do not use an explicit framework to guide their hypotheses development but simply draw on previous empirical work (Jeon et al., 2004; Jeon et al., 2006; Parte-Esteban & Devesa, 2011a, 2011b; Seetah, 2017; Jiao & Lu, 2019; Shin & Hong, 2020; Costa & Mota, 2021). Yet, a few other studies consider broad financial theories. In particular, Parte-Esteban et al. (2011), Parte-Esteban and Alberca-Oliver (2016), Parte-Esteban and Ferrer García (2014) and Sousa Paiva and Lourenço (2016) resort to agency theory (Jensen & Meckling, 1976), while positive accounting theory is applied by Gim et al. (2019), Poretti et al. (2020) and Parte-Esteban et al. (2011). Also, the pecking order of Myers and Majluf (1984) and Jensen’s control hypotheses (Jensen, 1986) offer the basis for the study of Gim et al. (2019). Importantly, none of the reviewed papers proposes a new theoretical framework to understand EM behaviour in the hospitality industry.

3.2.5 Research methods

Different methodologies can be used to detect the presence of EM within the hospitality industry. Most of the studies considered in this systematic review (14 out of 15) collect financial information from several databases and apply different data analysis techniques. In turn, Turner and Guilding (2011) use a mixed-methods approach, conducting semi-structured interviews and administrating a questionnaire (see Table 2 - category E). EM can be measured in several ways and by adopting several perspectives.

Accruals and real activities-based EM

In a narrow sense, the extant literature on EM identifies two main EM techniques: accruals manipulation (AEM) and real activities manipulation (REM). The first results from managers changing the accounting methods or changing estimates that were used and are reflected in the financial statements (Zang, 2012). Conversely, real activities-based EM occurs when managers intentionally make operating decisions affecting cash-flow levels (Ruiz, 2016).

Costa and Mota (2021), Gim et al. (2019), Parte-Esteban and Devesa (2011b), Poretti et al. (2020) and Sousa Paiva and Lourenço (2016) resort to the Jones Model (Jones, 1991) and/or its modified versions (i.e., Dechow, Sloan & Sweeney, 1995; Kothari, Leone & Wasley, 2005) to estimate accruals manipulation. Furthermore, Poretti et al. (2020) and Sousa Paiva and Lourenço (2016) look at the magnitude of the absolute value of the discretionary accruals instead of the actual value of such accruals. In contrast, while Turner and Guilding (2011) study EM through a single real activity manipulation, namely the capitalisation or expensing of asset- related expenditures, Parte-Esteban and Devesa (2011a) look at a set of variables associated with real activities manipulation, such as sales, operating expenses, gross margin, other expenses, interest expenses, taxes, extraordinary income, research and development (R&D), working capital ratio, growth and leverage. Jiao and Lu (2019) consider both AEM and REM in their paper.

Earnings quality proxies

Some of the papers included in this review are focused on EQ, employing different empirical proxies. For instance, Jeon et al. (2004) and Jeon et al. (2006) draw on the assumptions that the persistence of abnormal earnings is positively related to EQ (Siegel, 1982) and that engaging in EM reduces the persistence of earnings (Li, 2019) to use earnings persistence measured through Ohlson’s model (1995) as an EQ proxy (Dechow et al., 2010). Conversely, Parte-Esteban and Ferrer García (2014) combine a set of EQ proxies, creating a dimensional concept composed of four attributes: the persistence of earnings, the predictive ability of earnings, the variability of earnings and earnings smoothing. Seetah (2017) ascertains EQ by resorting to accruals quality, measured according to Dechow and Dichev's model (2002). In addition, considering accounting conservatism as an EQ proxy (Basu, 1997; Dechow et al., 2010), Shin and Hong (2020) analyse how firms apply conservatism in their accounting statement and find that conservative accounting increases the quality of earnings.

Meet or beat specific earnings targets

Some of the reviewed articles consider how accounting and financial benchmarks impact the EM behaviour of hotels. Burgstahler and Dichev's (1997) methodology is the most popular for testing for discontinuities near zero in the distribution of profits and changes in profit. Parte-Esteban et al. (2011) resort to that approach and examine how Spanish hotels use EM to beat certain benchmarks. In a follow-up study, Parte-Esteban and Alberca-Oliver (2016) use the same methodology to investigate the relationship between earnings benchmarks and the regional tourist flow. After confirming the practice of EM for benchmarking purposes, Parte-Esteban and Devesa (2011b) and Costa and Mota (2021) study EM through the discretionary accruals (see Accruals and real activities-based EM), while Parte-Esteban and Devesa (2011a) confirm that managers are not indifferent to the earnings figure and identify a set of REM variables that determine different behaviour around benchmarks (see subsection Accruals and real activities-based EM). In contrast, Jiao and Lu (2019) follow Gunny (2010) to identify the firms that manipulate earnings towards financial benchmarks and investigate to what extent the benchmarks in the hotel industry are achieved through REM or AEM (see subsection Accruals and real activities-based EM).

3.2.6 Determinants of EM

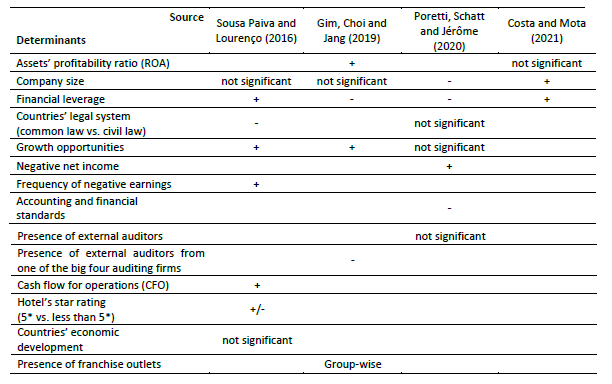

Some of the reviewed empirical papers explore the EM determinants of hospitality companies. Table 6 summarises the main variables employed and their impact on EM.

As can be seen, the literature seems to suggest that the determinants of EM may depend on the context in which they are studied. For instance, return on assets (ROA) positively affects EM only in franchise restaurants (Gim et al., 2019). Another study finds that company size positively influences EM practices in the Portuguese hotel sector (Costa & Mota, 2021). Conversely, Poretti et al. (2020) report a negative association between size and EM for the hospitality industry worldwide. Financial leverage has a negative effect on EM for non-franchise restaurants (Gim et al., 2019) and for countries with strong investor protection (Poretti et al., 2020) but a positive effect on hotel firms from civil law countries, including Portugal (Costa & Mota, 2021; Paiva & Lourenço, 2016). In fact, five-star hotels operating in civil law countries seem to engage in higher levels of EM than their counterparts in common law countries (Paiva & Lourenço, 2016). Research also shows that growth opportunities positively affect EM non-five-star hotels (Paiva & Lourenço, 2016) and franchise restaurants (Gim et al., 2019). Moreover, negative net income has a positive effect on EM (negative on EQ), especially in countries with strong investor protection, while Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) have a negative effect on EM only in countries with weak investor protection and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) do not produce any effect on EM (Poretti et al., 2020). It has also been found that the cash flow from operations and the frequency of losses are positively related to the level of EM for hotels holding five stars and for firms from civil law countries (Paiva & Lourenço, 2016). Finally, audit quality, measured by the presence of Big 4 auditing firms, is negatively associated with EM for both franchise and non-franchise restaurants (Gim et al., 2019).

4. Conclusions and implications

4.1 Main conclusions

The EM topic has been widely studied in the last two decades. Yet, there is little research on this area within the hospitality industry as this systematic review only finds 15 papers published in tourism/hospitality, accounting or finance journals that address such an important topic. Nevertheless, the scant literature suggests that managers working in this industry regularly engage in EM practices with the help of different manipulation techniques, which critically reduces the quality of the firms’ financial reporting. Most of the evidence on this topic comes from European countries and listed firms. Furthermore, researchers usually employ discretionary accruals models in their applied work and use firm- and country-level characteristics to investigate the main motivations for manipulating earnings. In addition, the empirical evidence seems to suggest that company size, financial leverage, growth opportunities, ROA, audit firm issues and the countries’ legal systems are the most relevant determinants of the EM practices that occur within the hospitality industry.

4.2 Research opportunities

The topic of EM practices in the hospitality industry offers a number of future research opportunities. In fact, we still do not know how certain non-financial characteristics affect such practices. One promising avenue of research in this area is studying the relationship between the EM practices of publicly listed hospitality firms and the characteristics of their board of directors (Feng & Huang, 2021; Osma, 2008; Petrou & Procopiou, 2016; Srinidhi, Gul & Tsui, 2011). In effect, although managing earnings is an aggressive accounting behaviour that managers carry out (Feng & Huang, 2021), evidence suggests that boards affect companies' financial performance in different manners (e.g., Song, Van Hoof & Park, 2017). Looking into this issue is important since this review shows that most of the extant studies focus on listed firms or, at best, consider a combination of listed and non-listed companies.

Interestingly, the previous point also suggests another research avenue in the context of the EM practices of the hospitality industry since privately held companies and not publicly listed firms make up most of this sector. However, only a few papers consider the EM behaviour of this industry’s non-listed companies and their respective motivations, which should be addressed by future research. In this context, family firms are especially relevant as they have a significant weight in the hotel sector of several world economies (Masset, Uzelac & Weisskopf, 2019) and exhibit particular characteristics, such as binding financial constraints and low monitoring. Hence, it would be interesting to study the EM practices of family-owned firms that compete in the hotel industry, an important issue that the literature has yet to explore. Future studies should also do the same for multinational hotel chains. In fact, these businesses are becoming more common and important within the hospitality industry, and as such, it would be a matter of interest to consider them in dedicated research.

An additional topic of research relates to the relevant methodological choices that inform the current empirical research. In particular, this SLR shows that most of the existing papers in the hospitality sector resort to accruals-based EM in their empirical applications by looking at the magnitude of the absolute value of discretionary accruals. Hence, only a few studies consider the value of discretionary accruals, a topic that should be additionally explored since it would allow capturing the type of manipulation that is being carried out by the hotels, and a more accurate understanding of the EM determinants. Similarly, we need studies that employ real activities-based EM models, a very interesting research avenue on its own as the hotel industry is mainly composed of unlisted firms, which are more prone to use different EM techniques to achieve their particular financial reporting goals (Burgstahler et al., 2006).

Another possible area of research deals with how regulation for investor protection affects the EM practices of hospitality firms. Sousa Paiva and Lourenço (2016) find that the level of EM is affected by countries’ legal systems, which are related to the strength of investor protection. Furthermore, Poretti et al. (2020) state that the degree of investor protection influences the association between EM and financial leverage. It would thus be interesting to verify to what extent the EM practices of this industry are affected by the level of protection granted to investors by the law. A possible extension of this topic refers to the accounting standards adopted by a given country. In effect, managers may exert their professional judgement differently depending on the reporting standards they must follow. This could also lead to distinct EM practices within the hospitality industry.

The COVID-19 crisis that started at the beginning of 2020 is also an important topic that must be considered in future research. In particular, the literature highlights that crisis periods influence management behaviour (Conrad et al., 2002; Kousenidis et al., 2013; Strobl, 2013; Trombetta & Imperatore, 2014). It follows that future research should explore to what extent this significant external shock has impacted the EM behaviour of hospitality firms.

Finally, all of the abovementioned topics can also benefit from the lack of evidence on the EM practices of hospitality firms operating in African countries and Oceania. Such countries have their own institutional, cultural and economic characteristics, which should provide a rich and different setting that could yield important insight into the EM behaviour of the hospitality industry.

4.3 Theoretical Implications

This systematic research shows that, so far, the empirical evidence on the EM behaviour of hospitality firms is not based on solid theory. In fact, currently, most studies simply do not resort to theory to guide their empirical design, and the exception are the few papers that consider general predictions taken from generic theories that were developed in the finance or accounting fields. This is possibly a problem given the particular characteristics of the tourism industry, which could explain why there is still no empirical consensus regarding many of the relevant aspects pertaining to research on EM in this sector. As such, this SLR clearly calls for researchers to develop a theory that could address this critical economic sector's specificities, which could also help enrich our understanding of the EM practices of firms competing in other industries across the globe.

4.4 Practical Implications

The scant empirical evidence reviewed in this paper suggests that managers working in the hospitality sector resort to earnings management practices when preparing their firm’s financial statements, which is a very important conclusion for this sector’s stakeholders. For instance, financial accounts are one of the most important sources of information for shareholders, who rely on them to understand the risk/return characteristics of their current and prospective investments. The government uses financial statements to determine the amount of taxes it can charge, while employees may resort to this type of information to envision their career prospects. Suppliers and customers can also learn a great deal by closely examining the financial accounts of the firms they are doing business with. Managing earnings is, thus, potentially harmful for a myriad of stakeholders who are actively engaged with the hospitality industry. As a result, the different regulatory bodies that have responsibilities in this area must develop tools to mitigate the negative consequences of these accounting practices. This is a key point given the growing importance and complexity of the hospitality industry for the world’s economy.

4.5. Limitations

This study is not without limitations. As Petticrew and Roberts (2006) stressed, systematic reviews are a form of retrospective, observational and selective research, and this creates biases. The subjectivity underlying the selection of keywords, search strings and exclusion/inclusion criteria influences the sample that is reviewed. As Pickering and Byrne (2014) highlighted, biases may also derive from not reviewing research published in languages other than English, which is our case. In addition, this paper does not resort to meta-analysis, which has become increasingly popular in systematic reviews (Petticrew & Roberts, 2006). However, this technique is recommended when there are many studies to be reviewed and when the selected papers address an identical conceptual hypothesis with similar research methods (Petticrew & Roberts, 2006; Velte, 2019).

Credit author statement

All authors have contributed equally. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Portuguese Science and Technology Foundation (FCT) through project UIDB/04020/2020 with DOI 10.54499/UIDB/04020/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/04020/2020) and project UIDB/04007/2020 with DOI10.54499/UIDB/04007/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/04007/2020).