Introduction

Economic integration processes, coupled with the phenomenon of market globalisation, have compelled firms to consider internationalisation as an inherent reality (Liébanas-Cabanillas et al., 2023; Rodríguez-López et al., 2023; Yilmaz & Konakloglu, 2022). International markets serve as a catalyst for business growth, particularly for firms or organisations with an international market strategy. Languages constitute a pivotal element of any community's culture. In the context of an intensely competitive global environment, individuals or organisations possessing proficiency in multiple languages enjoy a distinct advantage in participating in global trade and exchanges (Emmendoerfer et al., 2023; Li & Kalynaraman, 2012; Molinsky, 2007). The ability to navigate linguistic diversity enhances opportunities and effectiveness in international business endeavours. As such, linguistic skills are increasingly recognised as integral to successful engagement in the global marketplace, influencing strategic decisions and contributing to overall competitiveness.

Canale and Swain (1980) asserted that communicative competence comprises three components: the grammatical (pertaining to lexicon, semantics, and phonology), the sociolinguistic (related to sociocultural norms operating in human discourse), and the strategic (both verbal and non-verbal). Collectively, these components form the foundation for understanding the role of language in communication, particularly in advertising.

The use of foreign languages in advertising has given rise to what is termed a "linguistic fetish" (Kelly-Holmes, 2005): the effect of evoking sociocultural associations through a product advertised in a foreign language. More formally, this phenomenon is known as the country-of-origin (COO) effect, applied to a product advertised as typical of an original to a specific location, with its message conveyed in the language of that place (Hornikx & van Meurs, 2017).

Various authors have investigated the symbolic associations of foreign languages used in advertising (Hornikx & Starren, 2006; Kelly-Holmes, 2000, 2005; Sánchez-Duarte & Alcántara-Pilar, 2017). The published literature has also examined how firms utilise multilingual advertising campaigns to evoke symbolic meaning based on the audience's stereotyped perspective, previous experience, or knowledge of the country where the language is spoken (Piller, 2001). It is well-established that firms globally frequently employ foreign languages in their advertising (Alcántara-Pilar, del Barrio-García, Crespo-Almendros & Porcu, 2017; Hornikx, van Meurs & Starren, 2007; Weijters, Puntoni & Baumgartner, 2017). The central premise supporting the symbolic structures of interest in this work is that the use of foreign languages is not intended to communicate content; instead, it is designed to evoke the cultural associations that these languages bring forth (Alcántara-Pilar, del Barrio-García & Porcu, 2013; Haarmann, 1989; Hornikx, van Meurs & Hof, 2013; Kelly-Holmes, 2005; Piller, 2003; Ray, Ryder & Scott, 1991).

However, the premise upon which the idea of symbolism being conveyed by a language is based, and the "linguistic fetish" effect created, is that the recipient must be able to identify the language in question (Alcántara-Pilar et al., 2013; Hornikx et al., 2007). This forms the central premise under study in the present investigation. The study aims to analyse how the recipient's ability to identify the language used in an advertising message may affect the image they hold of the firm and the Word-of-Mouth (WOM) they generate about it. Neither of these issues has been examined in the literature to date. An experimental design is employed, exposing survey participants (all native Spanish speakers) to an advertising message in one of five languages: English, French, Italian, Russian, and Turkish.

2. Literature review

2.1 Language, thought and culture

The relationships among language, thought, and culture have long captivated various disciplines, including psychology, philosophy, sociology, and sociolinguistics (Agheyisi & Fishmann, 1970; Blanco Salgueiro, 2017; Canale & Swain, 1980; Giles, Bourhis & Davis, 1979; Gumperz & Levinson, 1996; Hymes, 1971; Moreno Fernández, 2009; Sapir, 1956; Whorf, 1939).

Since language constitutes a key feature of a group’s culture, language learning is concerned with achieving proficiency in linguistic codes and grammar and aspects inherent to the culture surrounding those elements, framing each act of communication. Different models developed since the 1980s define various dimensions of communicative competence, a notion established by Hymes (1971). Canale and Swain's (1980) influential model, initially designed for learning second languages, extends beyond grammatical competence to encompass attitudes, values, and motivations influencing language, its uses, and social interaction (Canale & Swain, 1996). This model includes sociolinguistic and strategic competence, addressing sociocultural norms and communication strategies (Canale & Swain, 1980).

Canale (1983) later modified the model, refining sociolinguistic competence and distinguishing it from discourse competence. The original model has informed various others, each adding unique nuances and refinements (Bachman, 1990; Bachman & Palmer, 1996; Celce-Murcia, Dörnyei & Turrell, 1995, among others). Some authors describe sociolinguistic sub-competence as cultural or intercultural (Oliveras, 2000), while others refer to sociocultural (Iglesias Casal, 1998) or cultural (Miquel & Sanz, 1992) as distinct competencies.

Exploring the relationships between language, thought, sociology, and philosophy leads to the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis (Whorf, 1939; Sapir, 1956). Under the "linguistic relativity" umbrella, various hypotheses posit that speakers of different native languages think and behave differently. These theories assume that language has cognitive effects and that diverse languages exert distinct cognitive effects. Neo-Whorfian interpretations tend toward more moderate readings, emphasising that language affects thought rather than determining it (Gumperz & Levinson, 1996; Blanco Salgueiro, 2017).

In sociology and psychology, numerous studies explore attitudes toward social reality. Agheyisi and Fishmann (1970: 137) stress the importance of such investigations in understanding language selection, code-switching, dialectal differences, and mutual intelligibility in multilingual societies. Linguistic attitudes influence social, cultural, and emotional values and play a pivotal role in group and individual identity (Moreno Fernández, 2009).

Linguistic attitudes refer to attitudes toward languages or linguistic varieties and communities of speakers-social or ethnolinguistic groups-who use a given variety. Giles, Bourhis, and Davis (1979) proposed two hypotheses: inherent value and imposed norms. The inherent value hypothesis posits that one language variety may be considered inherently "better" or "more attractive" based on aesthetic considerations. The imposed norm hypothesis suggests that a language variety may be judged on its attractiveness in relation to its use by a prestigious group. Attitudes are influenced by perceived status and prestige, whereas economically powerful groups attract positive attitudes. The level of standardisation and perceived facilitation of social climbing, economic prospects, or commercial exchange also influence attitudes toward a language.

2.2 Symbolic associations conveyed by foreign languages in advertising

The work of Kelly-Holmes (2005) constitutes an invaluable study of the efficacy of language in conveying symbolic values and sociocultural associations. The author elucidates the concept of 'linguistic fetish,' wherein products typically associated with a specific culture (country) are referenced in their original language in advertising and commercial texts. This practice is employed due to the associations it evokes among audiences engaged in multilingual marketing communications. The utilisation of foreign languages in advertising is not arbitrary; generally, the selection of the foreign language is based on its country of origin, which carries strong associations with the perceived quality of the advertised product (Hornikx et al., 2013). This alignment is analogous to the Country-of-Origin (COO) effect, positing that associating a product with a country consumers commonly link to that product is more effective than associating it with an unrelated country (Hornikx et al., 2017).

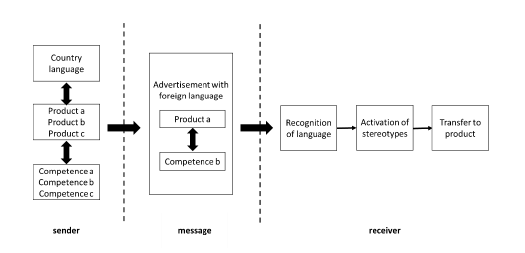

Consequently, if a firm chooses to incorporate a foreign language in its promotional materials, the selection hinges on what Kelly- Holmes (2000) terms the cultural competence hierarchy. This hierarchy organises specific products based on the degree to which they are commonly associated with different countries. Hornikx and Starren (2006) synthesised the findings of Kelly-Holmes (2000, 2005) and Piller (2001), creating a model of symbolic associations of foreign languages in advertising. Their model combines the perspective of firms creating multilingual advertising campaigns with the recipient's viewpoint in the process of symbolic meaning- making (Piller, 2001). Referring to Figure 1, the left-hand side is rooted in the cultural competence hierarchy, determining product types widely associated with specific countries and their perceived competence in producing certain goods (depicted in the left- hand column of Figure 1). The products and competencies attributed to countries are based on ingrained perceptions. Kelly-Holmes recommends using a foreign language in an ad promoting a product widely associated with the country of that language, enhancing positive traits and persuasiveness.

Figure 1: Symbolic associations of foreign languages in advertising from sender to receiver. Source: Hornikx & Starren, 2006, based on elements of the works of Kelly-Holmes, 2000 and 2005; and Piller, 2001.

The links between countries and their competence in producing specific products (Kelly-Holmes, 2005) stem from consumer perceptions based on direct experiences or indirect information from the media about various countries, their inhabitants, and their characteristics. The recipient's thought processes are depicted on the right side of Figure 1. Consider a product (perfume) advertised in French to convey elegance and style indirectly. The recipient first recognises the language, and then activates stereotypes associated with France and its inhabitants. Finally, it is posited that these stereotypical associations transfer to the product. If the audience considers French charming and elegant, they will similarly regard the perfume as charming and elegant, enhancing the ad's persuasiveness (Piller, 2001). However, a yet-to-be-tested element is precisely which associations are activated by using a given foreign language and whether these associations are positive, neutral, or negative.

2.3 The symbolic effect of foreign languages on advertising messages

Kelly-Holmes (2005) defines multilingual advertising as the use of multiple languages or voices in a market-discourse situation. Hornikx and Starren (2006) observe that the use of foreign languages in advertising is a widespread global practice, with "foreign language" defined as any language not official in a given country. The incorporation of foreign languages in advertising has gained popularity on a global scale (Alcántara-Pilar et al., 2017; Hornikx & Starren, 2006; Hornikx & Van Meurs, 2015; Hornikx et al., 2007; Sánchez-Duarte & Alcántara-Pilar, 2017; Weijters, Puntoni & Baumgartner, 2017).

Various authors have focused on the increasing use of foreign languages in advertising in specific regions, including the United States (Petrof, 1990), Europe (Gerritsen, 1995; Piller, 2003), South America (Alm, 2003), and Asia (Haarmann, 1989), among others. This strategic use of foreign languages aims to capture the audience's attention and evoke sociocultural associations that enhance the persuasive impact of an advertisement (Gerritsen, 1995; Piller, 2003).

Haarmann (1989) examined the prevalence of foreign languages in Japanese advertising, finding their widespread use depending on the symbolic value and associations triggered by specific languages in Japan (Puntoni, de Langhe & Van Osselaer, 2008). Martin (1989) demonstrated that English songs in ads targeting the French audience often did not entirely make sense, but their purpose was to draw on specific words or phrases to transfer value to the message.

From a sociolinguistic perspective, using foreign languages has proven to persuade consumers for several reasons. For instance, foreign languages can attract attention by surprising listeners who do not expect to hear a language other than their mother tongue (Burgoon, Denning & Roberts, 2002; Hornikx et al., 2013; Morales, Scott & Yorkston, 2012; Smeets, 2017). Moreover, foreign- language expressions attract attention due to their symbolic value, evoking specific associations transferred to the product and brand in the ad. The symbolic value of the foreign language is paramount, as it does not necessarily need to convey content but should trigger cultural associations (Alcántara-Pilar et al., 2013; Haarmann, 1989; Hornikx et al., 2013; Kelly-Holmes, 2005; Piller, 2003; Ray et al., 1991).

Research has also shown that some firms allocate significant advertising budgets to communicate product benefits in languages their target markets cannot speak. The rationale behind this is that expressions in a foreign language, under certain circumstances, can be more effective than equivalent expressions in the mother tongue (Hornikx & Starren, 2006; Hornikx & van Meurs, 2015).

The ability of individuals to identify the foreign language used in an ad (i.e., recognise its country of origin) is a crucial element of multilingual strategies (Kelly-Holmes, 2000). It is more significant than the language's literal meaning in evoking associations (Piller, 2001). Morales et al. (2012) and Hornikx et al. (2007) suggest that listeners generally attribute the attitude or symbolic meaning they associate with a foreign language variety to the product. This transfer of symbolic meaning may occur involuntarily, irrespective of whether the listener is aware of the persuasive intentions of the foreign language display in the ad.

In light of the published research, it can be affirmed that:

Sociolinguistic competence is rooted in an awareness of verbal and non-verbal sociocultural norms that empower individuals to interpret communication in terms of its social meaning (Canale & Swain, 1980). This interpretation can thus be applied to the realms of communication, publicity, and the media.

This social meaning is directly linked to the symbolic associations associated with language use (Kelly-Holmes, 2005) and the concept of linguistic fetish, wherein a cultural competence hierarchy associates certain products, by extension, with specific countries (Hornikx & Starren, 2006; Kelly-Holmes, 2000; Piller, 2001).

For a linguistic fetish to be established or a cultural competence hierarchy to emerge, the recipient is not required to comprehend the message in the foreign language. However, it is crucial that they can identify the language in question (Alcántara-Pilar et al., 2013; Hornikx et al., 2007; Kelly-Holmes, 2000; Martin, 1989; Piller, 2001).

The existing literature has examined relationships, specifically language-product type and language-characteristics, as well as the values attributed to advertisements based on the foreign languages employed. Nevertheless, none of the studies conducted thus far has investigated whether the recognition of language impacts the recipient's perception of the firm or the Word-of-Mouth (WOM) they generate about the firm. In alignment with the literature review, the following hypotheses are posited:

H1: The image recipients hold of the firm advertising will be more favorably perceived among individuals who recognise the foreign language used in the message than those who do not.

H2: The WOM generated by recipients regarding the firm advertising will be more positive among individuals who recognise the foreign language used in the message compared to those who do not.

3. Methodology

3.1 Independent variable, measures and experimental design

A between-subjects experimental design was deemed most appropriate for addressing the research questions. The independent variable was the foreign language used to present the advertising message, with five treatments: English, French, Italian, Russian, and Turkish.

Initially, the experiment assessed sociodemographic variables of the Spanish sample (all native Spanish speakers), including gender, age, and employment status. Subsequently, participants listened to an advertising message in only one of the five languages chosen for the experiment. Visual cues were absent, and each participant was exposed to the message in only one language. The content of the message was as follows:

"Years of experience and the loyalty of even the most demanding clients endorse us. Do not hesitate. Look no further. Nostromo is your brand. You won’t regret it."

In the message, deliberate omission of any reference to the sector of the fictitious company Nostromo was ensured to eliminate potential influence, aiming for the sole factor affecting results to be the language itself.

Participants were tasked with identifying the language employed in the message they had just heard. Subsequently, they indicated their proficiency in that language and whether they could speak it, providing a self-assessed proficiency level on the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) - ranging from 'I do not speak this language' to levels A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, or C2, with A1 representing the most basic proficiency (Alcántara et al. 2017).

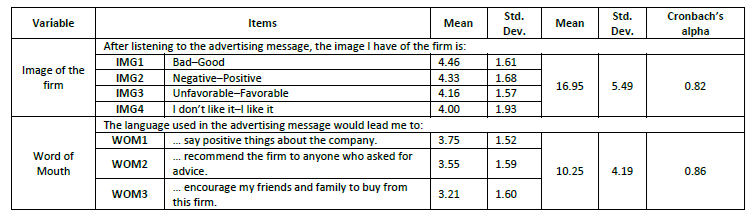

Following exposure to the message, participants rated their perception of the fictitious enterprise depicted in the message and the likelihood of engaging in Word-of-Mouth (WOM) communication. We employed a 4-item, 7-point semantic differential scale adapted from Petty, Cacioppo, and Schumann (1983) for the former. WOM was evaluated on a 7-point Likert scale adapted from Zeithaml, Berry & Parasuraman (1996) (refer to Table 1 for details).

3.2. Sample

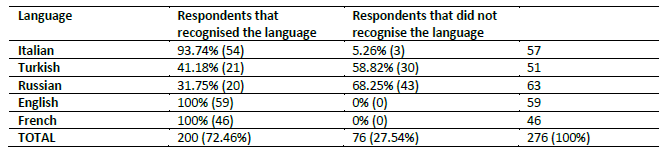

The final sample comprised 276 individuals, of whom 20.65% received the message in Italian, 18.48% in Turkish, 22.83% in Russian, 21.38% in English and 16.67% in French. The gender balance of the sample was 36.59% male vs. 63.41% female (see Table 2).

4. Findings

4.1 Manipulation checks for language

Before testing the hypotheses, we conducted a manipulation check for the experimental factor "language." Table 3 illustrates the number of respondents who were able to identify the language utilised in the version of the advertisement to which they were exposed.

4.2 Analysis of the psychometric properties of the scales

Before addressing the research questions, we assessed the reliability and validity of the multi-item scale employed to gauge the firm's image and Word-of-Mouth (WOM) directed towards the firm. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was employed to achieve this, revealing favourable psychometric properties (refer to Table 1).

4.3 Testing the hypotheses

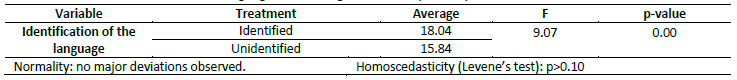

To test H1, which posited a relationship between the recognition of the foreign language used in the advertising message and the firm's image, we conducted an analysis of variance (ANOVA). The independent variable was the condition of language identification, and the dependent variable was the perception of the firm's image. The "identified" group consisted of respondents who, upon hearing the message, accurately identified the language used (irrespective of the assigned language). The "unidentified" group comprised respondents unable to identify the language in question.

As depicted in Table 4, the results reveal significant differences (p < 0.05). Consequently, we can affirm that when the advertising message was conveyed in a language correctly identified by the respondents, the firm's image obtained higher average scores compared to instances where a non-identifiable language was utilised.

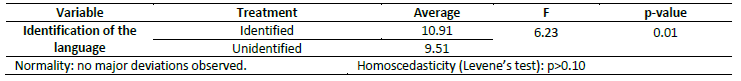

H2 hypothesised that there would be a more positive Word-of-Mouth (WOM) response regarding the advertised firm among individuals who recognise the language used in the message, as opposed to those who do not. To empirically test this hypothesis, we conducted an analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the same factor as in H1, with WOM as the dependent variable. Once again, the results yielded significant differences (p < 0.05), thereby substantiating the hypothesis. The foreign language identification was found to moderate WOM towards the firm, with higher average scores observed when respondents accurately identified the language compared to instances where identification did not occur (refer to Table 5 for detailed findings).

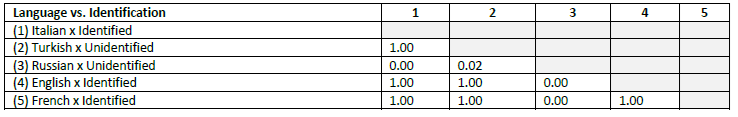

Considering the potential impact of the specific language used on the results, we conducted a Bonferroni correction. This correction involved examining the interaction between language (Italian, Turkish, Russian, English, and French) and the identified/unidentified status of the language. Notably, the categories "English x Unidentified" and "French x Unidentified" had no values, as indicated in Table 3. This absence is attributable to all participants exposed to English or French accurately identifying these languages. Additionally, groups with a sample size below 30, specifically "Italian x Unidentified," "Turkish x Identified," and "Russian x Identified," were excluded from the Bonferroni calculation.

Table 6 presents the results of the Bonferroni test, examining the interaction between language and identification and its impact on the firm's image. If the moderating factor were the language itself (as opposed to the identification of the language), differences would be expected between "Italian x Identified" and "Turkish x Unidentified," but this is not observed. Similarly, "Turkish x Unidentified" shows no differences compared to other languages, except for "Russian x Unidentified." Consequently, all elements in Table 6 exhibit significant differences. Thus, we can assert that the moderating factor influencing the company's image is whether or not the recipient identifies the language used in the advertising message. Additionally, including specific languages in the analysis does not enhance the results, except for Russian, which exhibits differences irrespective of identification.

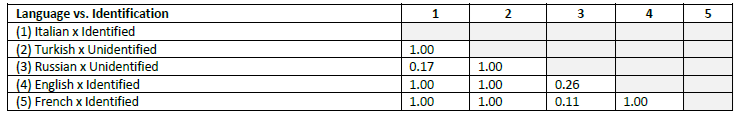

Following the identical procedure employed for company image analysis (refer to Table 7), a Bonferroni correction was applied to the Word-of-Mouth (WOM) examination. The language x identification interaction effect observed in this context emphasises that the pivotal factor contributing to disparities in recommendations for the firm is the individual's capacity to identify the language used in message communication.

5. Conclusions and implications

5.1 Conclusions

Many firms strategically employ foreign languages in their advertising, and existing literature has demonstrated that, in terms of effectiveness, this communication strategy yields superior outcomes compared to using the mother tongue in certain cases (Hornikx & van Meurs, 2015). The literature also indicates that it is unnecessary for the recipient to comprehend the content of the message in the foreign language. Instead, what holds significance is the symbolic structure of the language and the sociocultural associations that individuals attribute to the product based on stereotypes associated with the language and/or its country of origin. However, the critical factor lies in the recipient's ability to correctly identify the language being used. In other words, while understanding the message content is not crucial, failure to accurately identify the foreign language results in erroneous symbolic associations with the product-leading to a mistaken image of the firm and inaccurate Word-of-Mouth (WOM).

Therefore, this study aims to determine whether the recipient's recognition of a foreign language influences: a) the image formed of the advertising firm; and b) the subsequent statements or recommendations made by the recipient regarding the firm. This investigation builds upon the premise of the symbolic effect of foreign languages (Hornikx & Starren, 2006) and emphasises the necessity of correctly identifying the language to trigger the linguistic fetish effect (Alcántara-Pilar et al., 2013).

The study establishes that the recognition of the foreign language moderates the company image formed by the message recipient and the WOM they generate. Messages in Italian, English, and French are likely to produce an image of the firm and WOM that align closely with the linguistic results advertisers desire. However, it is crucial to note-especially for future studies-that approximately 30% of respondents did not recognise their assigned language. Therefore, while language recognition enhances image and WOM, those unable to identify the language used in the ad message will inevitably form some perception of the firm and generate WOM. Although this may be more positive for recipients recognising the language, it does not imply that those unable to recognise it will refrain from commenting on the firm or providing opinions, as they may hold stereotypes regarding the unidentified "sound."

The choice of language itself was not found to be a significant factor in image formation or WOM. This aligns with the conclusions of Piller (2001) and other authors, who argue that the symbolic meaning of the foreign language is paramount, not its content. This suggests that the specific language chosen for the ad is less critical. In the present study, Russian is an exception to this point, as it appears that this language poses challenges regarding the company image and WOM it generates, irrespective of whether the recipient recognised it.

5.2 Implications

The findings elucidated in this study carry profound implications for the intricate interplay between sociolinguistics and advertising, accentuating the nuanced importance of the recipient's recognition of the specific language deployed. The managerial ramifications, particularly within the realm of advertising, are multifaceted, pointing to a critical consideration in the strategic use of languages beyond the conventional English, French, or Italian. The inherent risk of non-recognition associated with using less ubiquitous languages emerges as a central theme, signalling potential pitfalls in communication strategies.

The outcomes underscore the imperative for commercial communication managers to tread carefully when venturing beyond the linguistic comfort zones of widely recognised languages. Non-recognition not only jeopardises the formation of a favourable company image but also engenders a perceptual dissonance between the intended message and the stereotypes held by recipients or those intended by the firm. In more severe instances, the lack of recognition can precipitate confusion and lead to associations with incorrect countries, characteristics, or products. This heightened awareness is especially crucial as companies navigate global markets and multicultural audiences, where language nuances play a pivotal role in shaping consumer perceptions.

To delve further into the practical application of these implications, examining the marketing strategies of prominent global entities provides valuable insights. For instance, multinational technology giants such as Apple and Samsung strategically leverage English in their global advertising campaigns. By doing so, they tap into the language's universal recognition, associating it with innovation, modernity, and technological prowess. This deliberate choice aligns with the findings of our study, emphasising the potential advantages of opting for a language widely acknowledged across diverse linguistic landscapes.

Contrastingly, luxury brands like Chanel and Louis Vuitton strategically incorporate French into their communication endeavours. Beyond the mere linguistic aspect, these brands capitalise on French's cultural prestige and historical associations with high-end fashion, sophistication, and elegance. This deliberate linguistic choice aligns with our study's emphasis on the symbolic meaning of languages and showcases how firms strategically tailor language selections to cultivate specific brand perceptions within their target audiences.

In essence, our study's implications extend beyond theoretical considerations, offering tangible insights for practitioners. The careful consideration of language choices becomes a dynamic tool for companies aiming to navigate the complex terrain of global advertising successfully. Recognising the potential impact of non-recognition, managers are prompted to reevaluate language selection strategies, emphasising the need for linguistic choices that resonate with diverse audiences while aligning seamlessly with the intended brand image.

5.3 Limitations and potential areas of research

The current study examines five languages, with three easily recognised by recipients and two identified by relatively few. The focus on only five languages implies that the implications may not be entirely generalisable, though they remain accurate. Nevertheless, some published data support the selection of these languages, such as English and Russian, both ranking among the top ten most spoken first languages globally, with millions of speakers (in third and eighth place, respectively).

5.4 Future research and applications

Given the finding that recipients' identification of the foreign language influences their formation of the firm's image and subsequent Word-of-Mouth (WOM), a crucial avenue for future research involves determining the nature of the image and WOM generated through identification. Recognising a language, such as English or French, may potentially evoke positive or negative image formation. This influence could be analysed to unveil stereotypical associations individuals make with identifiable languages. A subsequent step would involve distinguishing between recipients, contrasting those who merely recognise the language with those who also comprehend the content-once again, to analyse the image and WOM each group forms. Such an investigation would contribute to validating the premise underpinning the linguistic fetish effect, contingent on whether the results (image and WOM) align similarly for recipients understanding and not understanding the message content.

Another prospective research area could explore the non-identification of the language in question. For instance, the study might scrutinise cases like Turkish or Russian to better comprehend the image recipients associate with the firm and the direction of WOM when they fail to recognise the language-a circumstance likely to differ significantly among those who do recognise it, as previously outlined.

Specifically concerning Russian (the only language in this study found to independently affect image and WOM), it would be intriguing to establish the associations this language generates, both when identified and when not, corroborating that these associations should remain consistent, per the present study's findings.

The most urgent need lies in research expanding the investigation to include additional languages, providing valuable insights for advertisers contemplating the use of foreign languages to evoke product associations. A broader scope would further affirm that it is not the language itself constituting the key factor but rather whether the recipient correctly identifies the language - highlighting that extensive spokenness does not guarantee recognition.

Future research should explore the nuanced influence of foreign language recognition across diverse cultural contexts, investigating whether cultural factors, such as individualism-collectivism, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance, shape the effectiveness of language recognition in influencing company image and Word-of-Mouth (WOM). Another intriguing avenue for exploration involves examining the role of additional communication modalities, such as visual elements or cultural symbols, alongside foreign language use. The assessment of how a multimodal approach may either enhance or diminish the impact of language recognition on image formation and WOM is crucial. This entails incorporating experimental designs with visual stimuli in conjunction with foreign language messages.

Another potential area for future research includes conducting longitudinal studies to track changes in language recognition and its impact over time. The exploration of whether recognition patterns fluctuate in response to evolving societal attitudes, media exposure, or global events could provide valuable insights. Long-term observations have the potential to shed light on the stability of linguistic associations and their enduring effects on consumer perceptions.

Investigating how the choice of media channel (e.g., television, social media, print) influences the recognition and subsequent impact of foreign languages in advertising is essential. Analysing whether certain channels enhance or hinder language recognition and understanding how this variability affects image formation, and WOM would contribute significantly to the field.

These findings carry potential applications, such as the development of Strategic Advertising Guidelines. This involves creating practical guidelines for firms to strategically employ foreign languages in advertising based on language recognition dynamics, offering insights into optimal language choices considering the target audience, cultural context, and desired brand image.

Another application lies in Language Recognition Metrics, where tools and metrics can be created to measure language recognition effectiveness in real-time advertising campaigns. Developing algorithms or models that can predict the potential impact of language choices on image formation and WOM would aid advertisers in optimising their communication strategies.

Consideration must be given to Consumer Behavior Training, involving the development of training programs for marketing and advertising professionals. These programs aim to enhance their understanding of consumer language recognition patterns, equipping practitioners with the knowledge to anticipate and navigate potential challenges related to language recognition in diverse markets.

In the realm of Global Brand Management, providing recommendations for global brand management strategies is imperative. This involves considering the challenges posed by language recognition, offering insights into mitigating risks associated with non- recognition, and guiding brands in crafting culturally sensitive and effective global communication campaigns.