Introduction

Fluid and borderless organisational structures with complex units and work tasks lead to a rapidly growing research body of horizontal, shared, and participative leadership in theory and practice (Houghton et al., 2003). Recent studies have highlighted the benefits of horizontal, shared, and participative leadership in enhancing team effectiveness, innovation, and adaptability (Salas-Vallina et al., 2022; Scott-Young et al., 2019; Wang & Jin, 2023). Shared leadership is an interesting theory since it emphasises that leadership is no longer determined by a position alone but by employees' capabilities and the team's needs (Pearce & Sims, 2000). This approach emphasises collaboration, collective decision-making, and shared accountability among team members. Recent studies have underscored the importance of shared leadership in enhancing team effectiveness, innovation, and adaptability (Said & Kamel, 2023; Wang & Jin, 2023). Because shared leadership draws together the strengths of several people, it is a possible means of meeting a company's challenges by combining the strengths and leadership capabilities of several different people (Fitzsimons et al., 2011). While there has been disagreement about how to define shared leadership, almost all of these definitions agree that a team player influences and contributes to the development and success of shared leadership (Burke et al., 2003). A sense of autonomy and competence is required for effective, shared leadership. As a result of shared leadership, positive feelings and passion take shape, as well as a sense of mutual responsibility and a common identity (Pearce & Manz, 2005).

In recent years, proactivity has become increasingly heated among researchers and managers. A highly competitive organisation needs proactive staff. Their quick actions and effectiveness escalate the advantages of facing an event (Griffin et al., 2007). Job crafting is creative and proactive behaviour related to employees revising their jobs in a self-active way to realise engagement and meaning, which causes a flurry of attention (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). Organisations today rely heavily on knowledge, so mastering how to maximise the creation, sharing, and utilisation of knowledge is vitally important (Ipe, 2003). Sharing limited personal knowledge makes the knowledge boundless. Knowledge sharing has been supposed to be a catalyst for performance and creativity. The researcher verified knowledge sharing as a critical proactive ex-role work behaviour contributing to a competitive advantage in building organisational capacity and employees, especially in a knowledge economy (Argote & Ingram, 2000; Kogut & Zander, 1992).

Drucker came up with a widespread interest in psychological empowerment when employees are required to possess initiative and innovation in response to rapid globalisation and fierce competition (Drucker, 1988). This development suggests that psychological empowerment is a large part of improving employee effectiveness. Also, this kind of empowerment-sharing phenomenon benefits employees motivated to engage in proactive behaviour. This study investigates the cognitive processes underlying the influence of shared leadership. It synthesises the above views and current research, drawing upon social identity and self-determination theory frameworks. Specifically, it explores how shared leadership shapes individuals’ perceptions and behaviours within teams. The objectives of this study encompass the development and evaluation of a framework elucidating the influence of shared leadership on job crafting behaviours and knowledge-sharing dynamics among team members. Through rigorous analysis, this research seeks to uncover the mechanisms through which shared leadership shapes individual job crafting initiatives and facilitates the dissemination of knowledge within the team context. Also, psychological empowerment plays an agency role in proactive behaviour and shared relationships. By extending previous research, the present study sheds light on how shared leadership can enhance member proactivity.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1 Shared Leadership (SL) and Job Crafting (JC)

Research suggests that shared leadership fosters a culture of trust, mutual respect, and empowerment within teams, leading to higher levels of job satisfaction and organisational commitment (Salas-Vallina et al., 2022). The dynamic nature of shared leadership allows teams to leverage diverse perspectives, skills, and expertise, leading to improved decision-making processes and outcomes (Jiang, 2023). Recent literature highlights shared leadership as a key determinant of team performance and organisational effectiveness in today’s complex and fast-paced work environments (Wu et al., 2020).

As a comparatively innovative way, job crafting offered a shot to understand employees’ proactive behaviour. It refers to spontaneous employee behaviours focused on employee development to align with their preferences, motivations, and interests as they perform their duties during their jobs (Bakker et al., 2012; Berg et al., 2010). Employees take these proactive and intentional actions to redesign aspects of their jobs to better align with their personal preferences, strengths, and values (Lazazzara et al., 2020). A broadly accepted definition is job crafting, which is the design and implementation of an individual’s job, considering their personal characteristics, physical ability, cognitive abilities, and interpersonal relationships (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). Employees taking proactive ways to craft the job by themselves, the scholars described this behaviour as a customised, diverse, and bottom-up perspective; compared with a traditional centralised, top-down management approach, job crafting will be more capable of confronting the times of significant changes.

Another basic framework for job crafting theory comes from Dutch scholars representing the European school of job crafting research. They combined Job Demands and Resource (JD-R) models to define job crafting as the ability to change work requirements with employees’ needs. To change work requirements and resources, employees engage in job crafting proactively (Tims & Bakker, 2010).

Recent research has highlighted the positive effects of job crafting on employee well-being, job satisfaction, and performance (Rudolph et al., 2017). For instance, Rudolph et al. (2017) found that employees who engaged in job crafting behaviours experienced greater levels of engagement, autonomy, and fulfillment at work. Moreover, job crafting has been linked to reduced job stress, burnout, and turnover intentions (Plomp et al., 2019). By empowering employees to redesign their roles and tasks according to their preferences and strengths, job crafting fosters a sense of ownership, motivation, and alignment with organisational goals.

The power to initiate change is the driving force for job crafting. Managers can also encourage job crafting by creating an incentive environment when employees perceive freedom or empowerment toward roles in the work environment. In most cases, people will view reshaping their work as an opportunity to bring their ideas or values into play, and then they are likely to take action. Shared leadership reflects the state of participation of multiple team members. Through joint decisions and sharing responsibilities, team members share weal and woe (Hoch, 2013). While shared leadership and job crafting have been studied independently, emerging evidence suggests their complementary nature and synergistic effects on team dynamics and performance (Zhang et al., 2023). Shared leadership encourages collective responsibility and collaboration, creating an environment conducive to job crafting behaviours. Conversely, job crafting enables individuals to take on leadership roles and responsibilities, contributing to the overall shared leadership process of teams.

Recent studies have explored the intersection of shared leadership and job crafting, highlighting how leadership structures facilitate job crafting opportunities and vice versa (Luu et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021). For example, teams characterised by high levels of shared leadership are more likely to encourage and support job crafting behaviors among their members. Likewise, employees who engage in job crafting activities may exhibit leadership behaviours, such as proactively seeking feedback, mentoring colleagues, or initiating change initiatives.

H1: In a team, SL triggers members’ JC.

2.2 Shared Leadership (SL) and Knowledge Sharing (KS)

Knowledge has become a central motivating force and source of global economic development. In an age of knowledge explosion, no one in business can stop learning and become isolated with information. Knowledge itself is boundless for team members through interaction and communication sharing, increasing the value of existing knowledge (Cohen & Bailey, 1997), and through coordination and combination, diffusing expertise or information (Faraj & Sproull, 2000). As a prerequisite for enterprises to make full use of knowledge, knowledge sharing is the widely respected aspect of knowledge management in which embedded knowledge seeks, utilises, pushes, and pulls innovation (Jackson et al., 2006). Specifically, the widely recognised definition is the provision or receipt of knowledge, including experiences, skills, messages, technical, and ultimately, cooperation to execute tasks, find solutions, and innovate (Cummings, 2004; Haas & Hansen, 2007). Almost every enterprise creates a beneficial environment to promote employees’ knowledge-sharing behaviour. Knowledge sharing refers to the voluntary exchange and dissemination of tacit and explicit knowledge among individuals and groups within an organisation (Kim et al., 2020). Sharing knowledge facilitates learning, problem-solving, and innovation by leveraging employees' collective expertise and experiences. Recent research has highlighted the positive effects of knowledge sharing on organisational performance, innovation, and competitive advantage (Hanifah et al., 2022). Moreover, knowledge sharing is closely linked to individual and organizational learning processes, as it enables the transfer of best practices, lessons learned, and experiential knowledge across different units and departments (Kim et al., 2020).

It is hard to master how deep and comprehensive knowledge sharing is extended among team members. Since not everyone is born to share, on the individual level, grasping when and why employees have voluntary intent to share knowledge is crucial. From a shared leadership perspective, team members’ strengths are easier to exploit, and leaders more value personalities, needs, and ideas (Ensley et al., 2006). Moreover, based on the theory of reasoned action, scholars assume that employees tend to develop a more positive attitude if they expect that offering knowledge could enhance the team’s relationship. Also, the more empowered and valued employees are given, the greater their interest in sharing knowledge (Bock & Kim, 2002).

A previous study stated that by maximising the integration of limited organisational resources and information and breaking the relationship boundaries, shared leadership would improve the competitive advantage of organisations. By empowering team members to take on leadership roles and contribute their expertise, SL enhances individual motivation, engagement, and satisfaction (Jiang et al., 2020). Besides that, shared leadership has a crucial characteristic as the team members must have a friendly symbiosis to access and build on the sharing phenomenon and social interaction among teams (Carson et al., 2007). Granitz and Ward tested and pointed out that individuals prefer to share in an in-group where they identify and feel loyalty and respect rather than in an out-group (Granitz & Ward, 2001). Team members with shared leadership tend to feel the protagonist’s presence and are willing to distribute the influence and interactions among teams (Huang, 2013). Shared leadership structures provide the foundation for facilitating knowledge-sharing behaviours and practices among team members. Conversely, knowledge-sharing initiatives contribute to developing shared leadership capabilities as team members collaborate, co-create, and collectively solve problems.

Recent studies have explored the relationship between shared leadership and knowledge sharing, highlighting how shared leadership behaviours facilitate knowledge-sharing processes and vice versa (Imam & Zaheer, 2021). For example, teams with high levels of shared leadership are more likely to promote open communication, information sharing, and knowledge co-creation among their members.

H2: In a team, SL triggers members’ KS.

2.3 The Role of Psychological Empowerment (PE)

Psychological empowerment is a multidimensional construct that a generic individual psychological state or perception can trigger motivation and satisfaction about the task (Thomas & Velthouse, 1990). Building on the work, scholars developed and validated the instrument of psychological empowerment construct, resulting in growing theoretical and empirical research on psychological empowerment in the workplace (Spreitzer, 1995). It has been stressed that psychological empowerment inspires employees to value themselves, consider their ability to compare the work role, pursue meaningfulness through work, and confidently influence. Accordingly, employees who feel empowered psychologically are more likely to believe that they are competent, to think they could improve their work and influence others in a meaningful way, as well as to behave independently, actively, and progressively in their work (Spreitzer, 1995; Thomas & Velthouse, 1990).

It has been shown that psychological empowerment is positively associated with many factors, such as supportive environments and a participatory work environment, some of which have been confirmed by research (Spreitzer, 1995). Empirical studies have shown that employees with higher levels of psychological empowerment are more likely to experience job satisfaction, engagement, and proactive behaviours (Avey et al., 2011). Moreover, psychological empowerment has been linked to positive organisational outcomes, such as performance, innovation, and organisational citizenship behaviours (Khatoon et al., 2022).

Shared leadership stimulates employee participation in cooperation, creates advancing communication, and refuses the hierarchy, monopoly, and power of bureaucratic culture (Ensley et al., 2006). Under a shared leadership perspective, employees of an organisation create shared circumstances and participate in mutual interests. Replying to the characteristic serial appearance of official and unofficial leaders, shared leadership may lead the team to a fully matured, empowered stage (Conger & Kanungo, 1988; Pearce, 2004). Shared leadership facilitates empowerment by optimizing the components of meaningfulness, participation, objective, choice, and efficacy.

Several theoretical frameworks have been proposed to explain the relationship between SL and PE. For instance, social identity theory suggests that shared leadership fosters a collective identity and shared goals among team members, increasing psychological empowerment (Hogg, 2023; van Knippenberg, 2023). Additionally, self-determination theory posits that shared Leadership supports employees’ autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs, promoting psychological empowerment (Tang et al., 2020).

Recent studies have explored the relationship between SL and PE, highlighting their interdependence and mutual reinforcement. For example, Fransen et al. (2020) found that shared leadership positively fostered a sense of autonomy, competence, and impact. Similarly, Cobanoglu (2021) demonstrated that shared leadership behaviours, such as delegating authority and encouraging participation, were positively associated with employees’ perceptions of empowerment.

H3: In a team, SL triggers members’ PE.

Self-determination theory suggests that psychological empowerment supports individuals’ autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs, thereby promoting proactive behaviours (Cobanoglu, 2021; Khatoon et al., 2022). The more empowered employees, the more confident and comfortable they feel, so they are more willing to offer help and be more proactive. Psychological empowerment has been proven to encourage employees to voice, share opinions, and pursue transformation (Amabile et al., 1996). Another study suggested that psychological empowerment introduces employee confidence that they can design and program the work context, believe that they could make meaningful contributions, and are essential in the organisation (Gregory et al., 2010). In a word, psychological empowerment inspires employees to experience a positive work orientation. They are willing and feel capable of acting in advance or making personalised contributions via practices (Spreitzer, 1995). Specifically, psychological empowerment offers confidence to control at work, which allows employees to manage their work freely. Thus, empowered employees may sometimes perform their work in individualised and exceeded formulations. If employees are empowered psychologically, they can effectively perform craft and redesign their work based on their effort and initiative. Thus:

H4: In a team, PE triggers team members’ JC.

In many empirical studies, psychological empowerment has been shown to result in well-valued behavioural effects, such as increased voice and improvements in learning (Vallerand & Blssonnette, 1992) and creativity (Amabile, 1993). Similarly, empowered employees usually receive positive latitude for knowledge sharing and are less bound to equip and exchange information and knowledge. Moreover, for team members, greater responsibilities of sharing and supporting are awakened. Previous studies suggested that employees more proactively share knowledge if they find sharing knowledge with others interesting, meaningful, and helpful (Bock & Kim, 2002). It is proved that the more motivated employees are, the more willing they are to let the knowledge flow with others (Foss et al., 2009). Therefore, it is reasonable to look forward:

H5: In a team, PE triggers team members’ KS.

Moreover, the mediation mechanism that links organisational-level factors (inputs) to subsequent individual-level factors (outputs) might be able to explain how shared leadership might affect proactive behaviours through psychological empowerment through the mediation mechanism relating organisational level factors to subsequent individual-level factors, thus providing a mediator between structural interventions and the outcomes of those interventions (Chang et al., 2010). Employees’ psychological attachment to their organisation will probably increase along with their perception that the organisation always offers employees opportunities, empowerment, and connection (Joo & Shim, 2010). It can be proposed that psychological empowerment could be a reason to understand why employees proactively respond to shared leadership. Shared leadership, as a situational factor, enhances employee engagement and collaboration in work, which promotes psychological empowerment and thereby makes them more willing to behave proactively in the form of job crafting and knowledge sharing. Therefore, the following hypotheses can be offered:

H6: PE mediated the path of the impact of SL on JC.

H7: PE mediated the path of the impact of SL on KS.

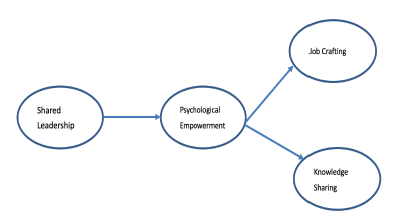

The research model can be summarised as follow in Figure 1.

3. Methodology

3.1 Sample

Because shared leadership is most appropriately developed for knowledge work orientation that relies on a team-construct approach (Pearce, 2004), a sample of South Korean firms employed in highly technical and knowledge-based teams were targeted for this study. To ensure the sample’s accuracy, we delivered 200 surveys through mail to departments or directly sent to team offices at four manufacturing firms. One hundred eighty-four survey responses were analysed. 64% of the sample were team workers in the R & D department, showing overwhelming maleness and 94% of the sample were male. 36.5% were aged between 36 and 40, and 24.4% were 26-30. The team size of 5 to 10 employees is the majority of the sample (32.6%). In terms of education, 75.5% got a bachelor’s degree. Furthermore, 73.6% had a job tenure of fewer than ten years. Thirty-six years was the participants’ average age, and the average work experience was 4.6 years.

3.2 Measurements

Given the research’s objective and hypotheses, the questionnaire adopted a 5-point Likert scale to measure the constructs’ validity. The demographic questions collected respondents' background information.

For operational shared leadership, it was decided to use the Hiller, Day, and Vance operational shared leadership scale (Hiller et al., 2006). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.944. For psychological empowerment, this study adopted Spreitzer's instrument, which comprises 12 items in four factors. (Spreitzer, 1995). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.899. For job crafting, we accepted the 15-item scale (Slemp & Vella-Brodrick, 2013) presented by Slemp and Vella-Brodrick. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.900. A 5-item scale about the attitude toward knowledge sharing was used for knowledge sharing (Bock et al., 2005), and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.804. Overall, Cronbach’s alpha value for each construct ranges from 0.804 to 0.944, all much higher than 0.600, and all scales’ reliabilities were considered appropriate.

4. Results

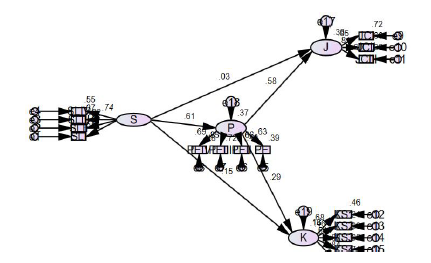

We first conducted Exploratory factor analysis (EFA). The results showed that four factors emerged with an extraction percentage of 67%. Based on the acceptable result of EFA, the following 2-step approach was employed. A good model fit appeared with χ²/df = 2.392; GFI=0.882; IFI=0.917; CFI=0.916. It was found that there was a strong correlation between the latent variables and the outcome variables: SL significantly and positively correlates with team member JC (r=0.377), KS (r=0.339), and PE (r=0.534). Additionally, PE positively correlates with JC (r=0.539) and KS (r=0.401).

To test research hypotheses, this study adopted Holmbeck’s 3-step approach by SEM (Holmbeck, 1997). Table 1 provides a detailed description of the direct paths. First, to examine the direct effects, consistent with the proposition of Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2, SL accounts for a significant amount of the variance in JC (estimate=0.531***) and KS (estimate=0.366***), so both hypotheses 1 and 2 are supported. Not surprisingly, the SEM analysis results support the prediction that shared leadership affects PE with the effective coefficient of estimate (estimate=0.716***), so hypothesis 3 is accepted. The results show a highly significant psychological empowerment in JC (H4) with a coefficient of 0.402***. Besides that, the result confirmed that PE would be positively associated with KS (H5) with an estimate 0.473**.

Table 1 presents the analysis results of direct paths.

Table 1 Analysis results of direct paths

| Paths | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p-value | Outcome |

| SL-->JC (H1) | .531 | .123 | 4.311 | .000 | Accepted |

| SL-->KS (H2) | .366 | .105 | 3.458 | .000 | Accepted |

| SL-->PE (H3) | .716 | .116 | 6.163 | .000 | Accepted |

| PE-->JC (H4) | .402 | .096 | 4.189 | .000 | Accepted |

| PE-->KS (H5) | .473 | .144 | 3.296 | .000 | Accepted |

Source: survey’s data

This study employed bootstrapping tests to discover the exact path of PE among SL, JC, and KS. We found that the direct effects have been reduced when psychological empowerment is acting. PE serves as a significant partial mediator in the relationship between SL, JC, and KS with coefficients of 0.287 (p< .001) and 0.335 (p< .001), respectively. We conclude that PE partially mediates the model since it is statistically significant and pointed in the exact positive direction. Both Hypothesis 6 and Hypothesis 7 are supported-table 2 summarises the results of mediating effects analysis.

Table 2 Results of bootstrapping test

| Mediating effects | Indirect coefficient | Direct coefficient | Degree of mediation |

| SL-->PE-->JC (H6) | .287** | .332** | Partial mediation |

| SL-->PE-->KS (H7) | .335** | .462** | Partial mediation |

Source: survey’s data

The analysis results of the conceptual model, including partial mediation effects, are depicted in Figure 2. This figure illustrates the direct relationships between SL, PE, JC, and KS. Additionally, it visualises the partial mediations involving PE concerning SL, JC, and KS.

5. Discussion

Taking Lao Tzu’s words to heart, people despise wicked leaders and respect the good ones. Instead, when the most outstanding leader shows up, people will crowd and say, ‘We did it together’. Co-creation is becoming a buzzword as scholars focus on leaders’ wisdom to foster work contexts in collaboration with followers. As a result of the theoretical basis of shared leadership, some valuable contributions have been made to its development. This study focused on shared leadership and examined how shared leadership contributes to employees’ proactive behaviours at the individual level. While prior research has laid the theoretical groundwork for shared leadership (Salas-Vallina et al., 2022; Tang et al., 2020), our study sought to deepen understanding by examining its specific effects on employee proactive behaviours at the individual level. We posited shared leadership as a relevant approach to navigating the complexities of modern organisational landscapes. This assertion aligns with recent scholarship emphasising the importance of leaders’ ability to engage followers in co-creation efforts. In detail, we considered shared leadership an appropriate way to address the increasing complexity in current organisational environments. By examining part of the mechanism within shared leadership and proactive behaviours, this study expands our understanding of the effects of shared leadership by highlighting the concepts of psychological empowerment, job crafting, and knowledge sharing. Results thus significantly contribute to the accumulating knowledge about how shared leadership influences team members’ behaviours.

The study proved that shared leadership significantly positively affects job crafting and knowledge sharing, especially when shared leadership triggers team members’ psychological empowerment. Generally, the greater their immersion in shared leadership among teams, the greater their psychological empowerment, which made them more willing to craft their jobs and share knowledge. Those results are consistent with those from preceding empirical studies on shared leadership. Back to the focus, we incorporate recent literature that underscores the importance of shared leadership in contemporary organisational contexts. For example, Salas-Vallina et al.(2022), Scott-Young et al. (2019), and Wang and Jin, (2023) emphasise the role of shared leadership in promoting work performance and adaptability within teams, aligning closely with our findings on proactive behaviours. By integrating recent research and situating our findings within the broader literature, we contribute to advancing understanding of the implications of shared leadership in modern work environments.

5.1 Theoretical Implications

We presented several theoretical implications of this study. First, the work offers additional theoretical scaffolding to support the notion that shared leadership can help address business challenges by combining the best leadership abilities of an entire team by highlighting the importance of shared leadership in today's work environment. The second reason is that this research is one of the first to elucidate the theory of shared leadership and empirically test its effects on individuals' behaviour variables on a micro-level. Third, by testing the agency’s psychological empowerment, team members' proactive and extra-role behaviours will likely be influenced by shared leadership in various ways. As tested, shared leadership within teams activates psychological empowerment. The study's results suggest that activated team members are more likely to perform proactive and extra-role behaviours, which indicates that psychological empowerment could be a potential agency predictor of employees’ proactive behaviour. Partial mediation suggests that while psychological empowerment partially explains the relationship between shared leadership and job crafting and knowledge sharing, other factors are also likely at play. This concept highlights the complex interplay between leadership, individual empowerment, and employee behaviours within organisational settings.

5.2 Practical Implications

The following discussion considers the implications of the practical aspects of this study. Leaders should envisage the skills to share leadership functions at the macro-group or organisational level. Such as being loving, devoted, and caring, having a positive attitude towards learning, being open to new ideas, having a unique vision, due diligence, influence, shared responsibility, and absorbing and shaping team members into a coherent work atmosphere. In addition, practitioners need to be aware that shared leadership may open up a new path in nurturing employees as leading candidates. The outcomes of this study may inspire managers to move beyond the essentially individualistic thinking that characterises popular perspectives on leadership effectiveness and development. It is also important to clarify the shared leadership capabilities of groups and how they might be enhanced. Managers may develop shared leadership to increase team members’ proactive and extra-role behaviours, especially job crafting and knowledge sharing. At the organisational level, organisations need shared leadership not as a series of characteristics or abilities among individuals at the top of the organisation but as a dynamic function that emerges from people bound together by some form of group task or goal.

To date, most of the research about shared leadership has looked only at Western countries. During the current wave of economic globalisation, South Korea has developed into an Asian country, driving firms in many markets toward more effective management modes. Teams are at the centre of these processes. Using the Korean sample as a basis, this study looks at employees who work in teams in different organisations. In South Korea, shared leadership shows high potential, offering high initiative and a cooperative spirit to organisations and employees. It is thus possible to contribute universally through the shared leadership framework.

6. Conclusions

This micro-level study emphasises the positive correlation between psychological empowerment and both job crafting and knowledge sharing, highlighting the significance of cultivating an empowering work atmosphere. This research delves into the connection between leadership and motivation, incorporating emerging concepts that are still evolving and variables experiencing renewed focus.

The sample size may be regarded as a limitation. Also, the participants were from different companies and groups, even though they all worked in knowledge work teams in the same region. In the future, a single organisation could be surveyed to control external contexts for the study.

Further research could consider the dynamic process of shared leadership. Another suggestion is to tag the sample with the timeline to observe and compare the level of shared leadership and its effectiveness. Also, as mentioned before, there is controversy over the definition of shared leadership. Various measurements demonstrate different perspectives.

Third, several scholars have suggested that combining shared and traditional top-down vertical leadership is the right direction for leadership development (Pearce & Sim, 2002; Pearce, 2004;). A helpful question for a future study might be how to effectively use shared leadership with other popular leadership constructs. For example, what effects may be expected if all of these attributes are combined in a team with shared, authentic, or transformational leadership?

When discussing shared leadership, we always map it to sharing experiences, responsibility, positive attitudes, maximising human resources, and sparking initiative. These are reasons why this study believes that shared leadership as a notion has potential for growth. Overall, the presentation of this study brings to mind the famous idea of “creating shared value” (Karwowska, 2021), but differently, as shown in this study’s results, shared leadership builds value within teams, and this “value” contribute to enhancing employee behaviors and organizational effectiveness.