Introduction

Characterised by its fragmented structure and inherent complexity, tourism is one of the most significant economic sectors globally. This prominence is underscored by the extensive volume of business it generates across various interconnected industries, including accommodation, restaurants, travel agencies and operators, transportation, car rentals, cultural services, leisure and entertainment, and retail trade. The scale of its economic impact is comparable to, or even surpasses, major global exports such as automobiles, petroleum gases, and food commodities (Candia & Pirlone, 2021).

Unsurprisingly, there is a broad consensus that the progress of tourism-as a sector, a collection of economic activities, or even a multidisciplinary field of knowledge-is intrinsically tied to the phenomenon of innovation, as originally conceptualised by Schumpeter (1934). However, the literature on innovation in tourism remains notably incomplete (Meneses et al., 2024; Nordli, 2017). While many publications and case studies exist, many are characterised by uncritical approaches and seldom address the full spectrum of activities comprising the tourism sector as an integrated whole.

Research on innovation in tourism enterprises remains scattered and fragmented (Işık et al., 2022). Among the limited number of theoretical-empirical investigations, studies employing quantitative techniques and data analysis dominate. This reliance on quantitative methods has led to critical gaps in understanding. For instance, Nordli and Rønningen (2021) highlighted the issue of hidden innovations in the tourism sector-innovations or related aspects that are overlooked due to the limitations of commonly used quantitative tools and techniques. Besides, most studies focus narrowly on one or two tourism branches (predominantly hotels) and are often conducted within specific contexts in Brazil and abroad.

In Brazil, for example, Pazini (2015) explored innovation from the perspective of travel agency managers in Curitiba. Rodrigues and Anjos (2016) conducted similar research with managers in the handicraft and restaurant sectors in São Luís. In Portugal, Aires (2017) examined innovation conceived by hotel managers in Aveiro. Pato and Leguíssimo (2024) analysed innovation and sustainability practices implemented by tourist lodgings in the Douro Region in Portugal. Leitão et al. (2023) analysed the impact of leadership on the relationship between innovation and performance in the Portuguese hotel sector and found a positive correlation between innovation and performance. Nordli (2017) investigated the characteristics of service innovations through the experiences of small hotel and entertainment company managers in Norway. Other works, such as those by Pikkemaat and Weiermair (2007), Succurro and Boffa (2018), and Aksoy, Alkire, Choi et al. (2019), emphasised the implementation of innovation but failed to examine its alignment with stakeholders' conceptualisations.

Despite these efforts, critical aspects of the dynamics and discrepancies between the design and implementation of business innovation in tourism remain underexplored. Addressing these gaps is essential for advancing management practices and developing effective mechanisms to measure, monitor, and evaluate innovative performance in the sector.

As in other sectors, innovation in tourism businesses is intrinsically tied to risks and uncertainties (Rodríguez-Sánchez et al., 2020; Verreynne et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2021). The dynamics of business innovation in tourist cities represent a collective construction of unique characteristics, where the subjective aspects underlying objective data and outcomes demand careful consideration and understanding. However, many published results and analyses of innovation implemented in tourism companies lack an explicit evaluation of the alignment between the innovation conceived and executed by stakeholders, particularly entrepreneurs and managers. To bridge this gap, studying innovative performance indicators, concepts, and typologies requires a qualitative, intra-sectoral, and exploratory-descriptive approach, which can capture the nuanced interplay of design and execution in the sector.

The primary objective of this article is to analyse the diverse meanings and implementations that innovation can assume across various branches of the tourism sector, focusing on evaluating the (mis)alignment between the conception and execution of business innovation. Natal, a prominent tourist destination in Brazil, serves as the geographical focus of this research. The study contributes theoretically and critically to the global body of literature on tourism innovation, emphasising the need to replicate globally recognised theoretical frameworks in the Brazilian context, particularly in under-researched tourist cities. This replication is vital for validation and uncovering territorial specificities that may necessitate revisions or redefinitions of existing concepts and tools for evaluating and monitoring innovation within the sector.

To achieve these aims, the study draws upon a literature review and 35 semi-structured interviews conducted with managers of tourism companies in Natal. These interviews were carried out over a longitudinal timeframe (2019-2023) to capture dynamic changes and insights. The transcribed content was systematically analysed and processed using SPSS 25, ensuring rigorous interpretation and data management.

The article is organised into five sections, beginning with this introduction. The second section explores the foundations and perspectives for conceptualising innovation and key aspects of its operationalisation in tourism enterprises. The third section details the methodology employed in the study, providing a comprehensive overview of the research design and data collection process. The fourth section, titled Results and Discussion, presents the data collected from participants and the studied companies, highlighting the relationships between the conception and implementation of innovation within these organisations. Finally, the conclusion summarises the main findings, theoretical and practical contributions, limitations, and directions for future research.

2. Theoretical background

2.1 Bases and perspectives for conceptualising innovation in tourism

Widely regarded as a cornerstone for businesses across all economic sectors, innovation is often described as a multifaceted and complex phenomenon (Drucker, 2014; Schumpeter, 1934). Schumpeter, a seminal figure in innovation theory, framed innovation primarily from an economic perspective, focusing on entrepreneurial and industrial dynamics as drivers of national economic progress. In his analyses, Schumpeter emphasised the pivotal role of the entrepreneur, whom he depicted as a unique and dynamic individual endowed with the energy and capability to create transformative changes that extend beyond the reach of the general population.

According to Schumpeter, entrepreneurs are extraordinary individuals whose behaviours and actions are the driving force behind significant societal and economic phenomena (Schumpeter, 1934). Far from being mere business operators or capital holders, entrepreneurs actively introduce radical technological advancements, fostering a dynamic and competitive economic environment (Briones-Peñalver et al., 2018). Their innovations generate new opportunities, reshape consumption patterns, and establish trends influencing broader market systems.

According to Schumpeter (1934), business innovation operates as a fundamental economic mechanism within the capitalist system, addressing needs and generating financial returns for innovators. He identified several forms that innovation could take:

Introduction of a new good: This involves creating a product previously unknown to consumers or significantly improving the quality of an existing good.

Implementation of a novel production method: Innovation may entail adopting a manufacturing process that has not been previously tested in the industry, even if it does not rely on a scientifically groundbreaking discovery. This could also encompass entirely new ways of marketing a product.

Opening a new market: This refers to accessing markets that the processing industry in a specific country has not yet entered, regardless of whether those markets existed.

Acquisition of a new source of raw materials or semi-finished goods: Includes securing resources, whether newly discovered or created out of necessity.

Creation of a new industrial organisation: Establishing novel business structures or systems forms falls under this category.

As Schumpeter described, innovation's essence is transforming an invention or idea into something commercially viable. This process includes its development, conversion into utility, and eventual acceptance within a social system, a crucial step for its diffusion and widespread adoption (Drucker, 2014; Schumpeter, 1934).

Nearly all studies on innovation in tourism companies draw upon this conceptual foundation, which also underpins the Oslo Manual-a key reference providing internationally comparable guidelines for collecting and interpreting innovation data, particularly within private enterprises (Aires & Varum, 2018). The Oslo Manual defines innovation as: "The implementation of a new or significantly improved product (or service), or process, a new marketing method, or a new organisational method in business practices, workplace organisation, or external relations" (OECD, 2005, p. 46).

While this serves as a crucial starting point for understanding innovation, scholars have noted its limitations when applied to tourism. Schumpeter's classical definition, which prioritises technological innovation, is often considered too narrow to fully encapsulate the diverse and dynamic nature of innovation within the tourism sector (Camisón & Monfort-Mir, 2012; Nordli & Rønningen, 2021; Omerzel, 2016; Verreynne et al., 2019).

As dynamic and complex phenomena, innovation and tourism are deeply influenced by territorial singularities, evolving over time and across contexts. This dynamism calls for more critical (re)definitions that account for subjective and objective dimensions of tourism business innovation (Rigelsky et al., 2022; Tajeddini et al., 2020). Existing literature highlights the necessity of transcending purely technical interpretations of innovation, advocating for more comprehensive and nuanced approaches (Nordli, 2017).

The characterisation of business innovation in tourism extends beyond technological advancements to include significant novelties and improvements in organisational and marketing practices. These innovations often emerge from the firm's interactions with its stakeholders, underscoring the importance of relational and collaborative dynamics in fostering innovation (Bachmann & Destefani, 2008; Booyens & Rogerson, 2016; Camisón & Monfort-Mir, 2012; García-Pozo et al., 2018; Poetry et al., 2021).

A pivotal aspect of the discussion on innovation in tourism involves analysing the meanings and individual perspectives of key figures, such as business managers, who hold the potential to influence broader collectives (Pazini, 2015; Rodrigues & Anjos, 2016; Rodríguez-Sánchez et al., 2020). Although inherently limited, the individual perspective-rooted in Schumpeterian logic and emphasising the role of entrepreneurs-has received significant attention in research (Aires & Varum, 2018).

This focus on individual viewpoints provides valuable insights into sectoral innovation's structural, interactive, and systemic dynamics. These perspectives help uncover critical elements that shape innovation within the tourism industry, aligning with broader frameworks of innovation dynamics and stakeholder interactions (Bachmann & Destefani, 2008; Freeman et al., 2020; Tajeddini et al., 2020).

The economic activity of tourism is a complex, interconnected system comprising enterprises, locations, relationships, strategies, and resource utilisation (Purwono et al., 2024). Entrepreneurs in this sector are acutely sensitive to and reliant upon various stakeholders' dynamic spatial-temporal contexts and evolving demands-not limited to tourists or travellers. To thrive in this environment, they must continuously reinvent their approaches, adapting to and fostering a market driven by the consumption of experiences (Tiwari et al., 2023), which often transcends the need for physical displacement.

Entrepreneurs' conceptualisations of innovation within tourism largely align with classical literature. As in other sectors, innovation in tourism signifies renewal, the pursuit of significant and ongoing improvements, and the reconfiguration of systems-whether physical, relational, or virtual-providing a competitive advantage to the organisation (Khalifa et al., 2023; Sharma et al., 2024). It encompasses (de)integration processes, both personal and organisational interactions, the acquisition, sharing, or imitation of knowledge, and the management of resources, both human and automated. Innovation entails isolated or collaborative strategies, addressing identified challenges, and creating added value by fulfilling human needs (dos Anjos & Kuhn, 2024).

These foundational elements and interpretations of innovation remain consistent across the diverse tourism subsectors, emphasising their universality and relevance to the broader industry.

In summary, business innovation in tourism can be understood as a network of formal and informal collaborative arrangements through which individuals and organisations share knowledge, generate value, and combine offerings to create sustainable solutions that address identified needs. In this context, sustainability encompasses three core dimensions: minimising environmental impact, ensuring financial viability, and promoting social equity and benefits (Santos et al., 2022; Santos et al., 2024; Streimikiene, 2023; Veiga et al., 2018).

Tourism innovation is multifaceted, reflecting both the form-the functional domain where it is realised-and the impact-the geographical scale of its effects, whether local, regional, national, or international (Hall & Williams, 2019). The concept of innovation, or "service logic" in tourism, as Nordli (2017) noted, encapsulates a firm's capacity to adapt to and manage change effectively, fostering the co-creation of value with employees, suppliers, customers, and partners.

2.2 Aspects of innovation implemented in tourism enterprises

As outlined in the Oslo Manual (OECD, 2005) and widely adopted in research, innovation is based on a taxonomy categorising innovation by implementing new initiatives or improving existing ones within companies (Verreynne et al., 2019). Four principal types of innovation practices are highlighted: product, process, marketing, and organisational innovation. Product innovation refers to introducing a product or service that is new or significantly improved in terms of its characteristics and intended uses. This includes enhancements to its capabilities, components, materials, ease of use, or other functional attributes (Alonso-Almeida et al., 2016; Elzek et al., 2020; Panfiluk, 2021; Pivcevic & Pranicevic, 2012; Thomas & Wood, 2014). Hjalager (2010), along with Booyens and Rogerson (2016) and Krizaj et al. (2014), further emphasise that these innovations are directly perceivable by customers and considered novel, either within the global market or within the firm itself (Krizaj et al., 2014).

Product innovation also encompasses significant environmentally driven changes and renovations to physical spaces, infrastructure, and facilities (Aires, 2017, 2018; Alonso-Almeida et al., 2016; Bachmann & Destefani, 2008). Hjalager (2010) highlights a growing trend toward design diversification and developing services and products tailored as intelligent solutions to address new problems and pre-defined market segments. In the hospitality sector, studies have identified distinctive qualities such as aesthetics, well-being, and personalised comfort as key aspects of product innovation (Nordli & Rønningen, 2021; Santos et al., 2020; Succurro & Boffa, 2018).

Process innovation refers to implementing a new or significantly enhanced method to improve operational performance, facilitate the production of goods or services, and optimise their distribution to consumers (Marques & Didonet, 2024). This type of innovation often involves back-office initiatives designed to boost efficiency, productivity, and workflow. Examples include innovations based on Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs), upgrades to integrated management operating systems, and adopting advanced techniques, equipment, or software. These innovations often deploy applications and platforms to enhance service delivery and operational effectiveness.

In many instances, process innovation is closely tied to technological applications across various domains, such as tourism products, marketing strategies, organisational frameworks, and environmental practices (Rita et al., 2024). It reflects an effort to adapt to or stay ahead of market trends and demands through modernised and streamlined processes (Aksoy et al., 2019; Succurro & Boffa, 2018; Volo, 2006).

The application of tourism service technologies includes automation using robots, faster and more efficient or radically new preparation methods, sensor-controlled processes, energy, time, labour savings, waste reduction, and improved sanitation (Calderón-Fajardo et al., 2024). These technologies also aim to reduce bureaucracy, speed up service delivery, and provide greater operational flexibility (Camisón & Monfort-Mir, 2012; Hjalager, 2010; OECD, 2005). Typically, process innovation facilitates other types of innovation and rarely occurs in isolation. High-impact innovations, particularly those involving customised ICT-based systems, are more frequently observed in specific group headquarters, especially in the hotel, travel agency, and transportation sectors.

The majority of firms implement process innovation primarily to imitate or keep pace with the technological advancements of competitors, partners, or other organisations in their market (Panfiluk, 2021; Pivcevic & Pranicevic, 2012; Verreynne et al., 2019). Frequently, tourism companies opt to purchase hardware, software, systems, or technology rather than develop these solutions in-house (Booyens & Rogerson, 2016; Pikkemaat & Weiermair, 2007; Succurro & Boffa, 2018). Regardless of the approach, positive effects are more readily achieved when ICT is integrated with other managerial strategies (Hjalager, 2010; Omerzel & Jurdana, 2016). The concept of "human and optimised resource management" emphasises the indispensable role of the human element, which complements technological advancements by enhancing performance and outcomes in tourism companies. This includes skills development and effective human resource management (HRM).

The OECD (2005) defines marketing innovation as the implementation of a new or significantly improved method or practice, encompassing improved customer orientation, access to new markets, or enhanced positioning of products or services in the market, all with the goal of increasing sales. Several authors, including Verreynne et al. (2019), Elzek et al. (2020), and Panfiluk (2021), highlight that predominant marketing innovations in tourism firms often involve enhancing or transforming e-marketing initiatives, identifying and entering new or existing markets, forming strategic alliances for product dissemination, rebranding or redefining brand identity, and bundling products. This category also includes collaborative marketing initiatives, often driven by public agencies seeking to promote and enhance tourism destinations. These efforts typically involve leveraging unique territorial characteristics, such as natural, environmental, or cultural heritage to attract visitors. Changes in marketing methods and practices are usually a response to shifts in competitive strategy, which frequently arise from internal and external interactions of the company. For instance, strategies adopted by competitors, strengthened customer relationships, employee and managerial input during meetings, and the acceptance of stakeholder suggestions often lead to marketing shifts. These dynamics may result in decisions like replacing traditional print media with digital marketing and social media campaigns (Booyens & Rogerson, 2016; Camisón & Monfort-Mir, 2012).

The fourth type, organisational innovation, as classified by the OECD (2005), refers to the implementation of a new or significantly improved change in a firm's structure-whether tangible or intangible-its management methods, business practices, negotiations, core operations (such as logistics and distribution), workplace organisation, or external relations with stakeholders. These innovations aim to enhance the firm's use of knowledge, improve the quality of its products or services, boost workflow efficiency and productivity, and/or reduce administrative or transaction costs (OECD, 2005; Poetry et al., 2021).

A notable subtype of organisational innovation is managerial innovation, which focuses on developing new methods of organising business processes, empowering staff, offering financial or non-financial rewards for exemplary work, and improving workplace satisfaction (Hjalager, 2010). Furthermore, new forms of collaborative or organisational structures, such as clusters, networks, and alliances, can lead to additional innovation types. These include market innovation (Volo, 2006), institutional innovation (Hjalager, 2010; Krizaj et al., 2014), and structural innovation (Booyens & Rogerson, 2016).

More than other types, organisational innovation heavily relies on a company's capacity to cultivate strategic relationships with stakeholders and make decisions grounded in a socially constructed team spirit, adding complexity layers (Poetry et al., 2021). Strengthened relationships with public and private institutions can yield numerous benefits, including inclusive, philanthropic, voluntary, and collaborative actions that are mutually advantageous for all parties involved (Booyens & Rogerson, 2016; Elzek et al., 2020; Panfiluk, 2021).

Understanding the four primary types of innovation as defined by the OECD (2005) enables the identification of nuanced dynamics within the tourism sector. These dynamics often reflect stakeholders' influence on implementing business innovations (Booyens & Rogerson, 2016; Panfiluk, 2021). Typically, such innovations arise from incremental yet meaningful improvements made over relatively short time horizons. These improvements, while usually visible and impactful, are often challenging to protect or patent (Camisón & Monfort-Mir, 2012; Hjalager, 2010; Nordli, 2017; Nordli & Rønningen, 2021; Omerzel & Jurdana, 2016), making them susceptible to imitation by competitors.

Customers, employees, and other organisations play a significant role in shaping the implementation of innovation within tourism businesses, regardless of their inclusion in formal groups (Khalifa et al., 2023). The ongoing pressures exerted by these diverse interest groups in their pursuit of satisfaction stimulate the capacity of tourism businesses to respond. These responses often manifest as specific adaptations or advancements within the recognised types of innovation.

The literature identifies several more specific types of innovation relevant to the tourism sector:

Customer Innovation: This involves implementing new products, services, processes, or practices aimed at addressing customer needs or suggestions, including those from potential consumers (Bachmann & Destefani, 2008);

Employee Innovation: Defined as initiatives to meet the needs or ideas gathered from internal or external employees, collaborators, or partner organisations. This type of innovation may arise from participation in industry events, competitive monitoring, or suggestions from partners (Bachmann & Destefani, 2008);

Social Innovation: This encompasses the creation or significant improvement of products, services, processes, or practices designed to deliver social benefits, particularly to underserved or disadvantaged groups. Unlike corporate social responsibility, social innovation is explicitly tied to facilitating social change rather than providing aid or charity. For instance, as noted by Booyens and Rogerson (2016), social innovation aims to create lasting societal impacts and might include rewarding or offering discounts to encourage socially beneficial behaviours (Aksoy et al., 2019; Elzek et al., 2020; Panfiluk, 2021);

Structural Innovation: This refers to implementing new or significantly improved collaborative or regulatory frameworks, networks, or initiatives designed to maximise benefits for the local economy, community, or destination. Structural innovations often extend beyond the scope of individual companies, driving changes such as new regulatory policies, collaborative marketing strategies, or initiatives to promote the destination on a larger scale (Booyens & Rogerson, 2016).

These specific types of innovation often transcend the boundaries of individual organisations, fostering broader structural changes, facilitating new regulatory or collaborative initiatives, and ultimately promoting holistic growth for the local and regional economy.

Distinguishing between types of innovation is inherently challenging, as innovative actions often occur in clusters, with fine lines separating or overlapping their boundaries (Omerzel, 2016). An innovation introduced in one domain frequently catalyses subsequent innovative actions in other areas. This interconnectedness highlights the complexity of categorising innovation within clearly defined types. To conclude this section, Table 1 summarises the categories or types of innovation and the authors referenced in the empirical research.

Table 1 Synthesis of the types of innovation and authors used in the research

Source: Own elaboration.

Table 1 serves as a valuable guide for readers, highlighting the sources that informed the discussion and the development of the research instrument. It can also be a reference for replicating the tourism innovation typology in various contexts. Specific territorial factors and the predominant management structures within companies may indicate the need to broaden the innovation typology. For instance, managers' profiles, generational characteristics, and the presence of family-based shareholding structures in tourism companies can significantly influence innovation dynamics. Based on organisational identity theory, family-run hotels often leverage their core values to build a distinct family firm image, enhancing relationships and providing a competitive edge (Pikkemaat et al., 2019; Schönherr et al., 2023). Whether by confirming or challenging globally recognised standards locally or by identifying new, context-specific types of innovation, such insights contribute meaningfully to advancing knowledge in the field.

3. Methodology

This research is descriptive, exploratory, and applied, grounded in the interpretivist paradigm. Its techniques are primarily qualitative, focusing on the language, expression, and understanding of the participants involved. The study aims to generate knowledge to address a specific problem, providing insights for practical interventions in a particular context (Lakatos & Marconi, 2020; Maxwell, 2013). It employs both secondary and primary data sources, with data collected using a semi-structured interview script.

Regarding its methodological approach, the research is primarily qualitative but incorporates quantitative elements, utilising content analysis and simple descriptive statistics. Managers were selected as participants based on recommendations from previous studies, such as Booyens and Rogerson (2016) and Nordli (2017). The location was chosen because Natal meets criteria that position it competitively on the international stage, enhancing its strategic market potential.

The current scenario, particularly after the pandemic peak, is characterised by increased demand for experiences centred around green areas and the region's natural conditions. These attributes and Natal's well-regarded hotel infrastructure and business networks in the so-called 'City of the Sun' have solidified its position. According to the Ministry of Tourism's Business Survey research, it was reported as the most in-demand Brazilian national destination in January 2021 (UNWTO, 2020).

As part of our research process, we engaged in both synchronous and asynchronous communication, conducted on-site observations, and performed exploratory tests (pilots) with managers from tourism businesses across seven different local segments: hotels, restaurants, car rental companies, travel agencies, entertainment parks, historical, cultural enterprises, and craft shops. These initial face-to-face meetings at the investigated businesses were scheduled in advance based on the interviewees' availability for in-person interaction. As Aires et al. demonstrated, these strategies proved essential for refining and finalising the interview script questions (2022).

Criteria for the inclusion and exclusion of research participants were defined in advance. The target participants for this research included: a) Managers or legal representatives of tourism enterprises headquartered in Natal; b) Enterprises classified as tourism- specific activities, such as hotels (with a minimum rating of three stars), catering, transport and car rental, travel agencies, cultural services, recreation and leisure, events, or tourism retail trade branches; c) Businesses holding the Cadastur seal from the Ministry of Tourism; and d) Enterprises that have been established for at least three years and are actively registered with the Board of Trade of the State of Rio Grande do Norte at the time of the interview.

To achieve a more precise definition of the population and target population by subsector, our analysis was based on the National Classification of Economic Activities (CNAE). Using a database from the Ministry of Tourism (Mtur, 2019), our searches identified 336 tourism companies with the Cadastur seal. It is important to note two contrasting situations regarding companies registered with the Ministry of Tourism: for some, the seal was optional, while for others, it was mandatory. One of the primary challenges of the survey was conducting an equal number of interviews across the different categories of businesses, especially given the high default rates in Brazil.

Another criterion for defining the target population was to include only businesses listed on online rating and review platforms (such as Booking and TripAdvisor) with a rating of "very good" or "excellent." The study conducted 35 valid interviews, with five interviews for each of the seven business categories, covering tourism enterprises of various sizes and activity branches. It is important to note that this number of interviewees does not constitute a representative sample of all sector activities in the city. However, selecting five interviewees per category was deemed an appropriate strategy to meet the research objectives, providing a meaningful and relevant sample for analysis and interpretation. Each interviewee could represent only one enterprise, even if it belonged to a larger business group.

To ensure consistency and comparability across participants' responses, standardised interview protocols were used in all cases, adapted to the specific contexts of each category. Furthermore, a single researcher conducted all face-to-face interviews, a deliberate choice to minimise potential variations in interview style, relationship building, and data collection procedures.

Based on these considerations, the following were excluded from the study: a) Managers or legal representatives of tourist resorts without the Cadastur seal or with less than three years of experience managing the resort; b) Managers or legal representatives of resorts not listed or evaluated on public domain review websites (such as Booking and TripAdvisor) or lacking online comments about their reputation, particularly those without a "very good" or "excellent" rating; and c) Managers or legal representatives of hotel resorts with no rating or below three stars.

Regarding ethical considerations, the study adhered to the guidelines of Resolution No. 510, 2016, of the Brazilian National Health Council. This resolution establishes the standards applicable to research in Human and Social Sciences involving data directly obtained from participants, identifiable information, or procedures that may pose risks beyond everyday life. Initially, the snowball technique was employed to facilitate access to the target business community and obtain their consent for participation. In this method, one interviewee recommends and invites another they trust, and the process continues until saturation is reached (Aires et al., 2022; Fontanella et al., 2011; Hennink & Kaiser, 2021). This approach was particularly effective in addressing the challenges posed by the high crime rates in Brazil, which foster distrust and reluctance among businesspeople to participate in research. While this barrier was anticipated, the technique helped to overcome it partially.

The first interviewee was a director of a four-star hotel, recommended by a restaurant entrepreneur with whom the pilot test was conducted. From the outset, all study aspects were thoroughly explained to the participants, ensuring they understood the research and provided informed consent for their participation.

After each interview, the interviewee voluntarily made the initial communication and invitation to another individual within the same target population. It is important to note that the interviewers verified each referral to ensure compliance with the companies' pre-defined selection criteria. Following this confirmation, the subsequent steps were carried out as follows: 1) Insertion, status, and control of the service in the database; 2) Communication via email or telephone call: This included a presentation of the interviewers, the objectives and relevance of the research, awareness-raising, clarifications, and an invitation to participate in the study; 3) In person visit to the enterprise; 4) Scheduling and/or conducting the face-to-face interview.

This approach continued across each of the seven categories of companies until the pre-established metric- a maximum of five interviewees per category-was achieved or until interviewees provided no further referrals. The combined use of these methodological data collection strategies proved effective in reaching members of the target population with greater social influence and visibility.

The interviews, which had an average duration of 20 minutes, were conducted over different periods: from January 15 to March 15, 2019, and from March 30, 2020, to April 20, 2021. To ensure consistency between the innovations conceived and those implemented over time, the companies were monitored until January 2023, primarily through their social media channels and official websites. These distinct data collection and analysis intervals allowed the study to account for the impact of the pandemic and the acceleration of digital transformation. This approach provided valuable insights into the dynamics of innovation over time.

The field approach employed in this study involved revisiting and collecting data from the same set of companies over time, constituting a longitudinal study. The study aimed to capture changes, trends, and company developments by adopting this approach. This methodology provided valuable insights into the dynamics of the phenomenon under investigation and enabled the analysis of potential causal relationships.

Conducting a longitudinal study offered unique opportunities to observe and analyse changes within the same companies, enhancing the understanding of the research topic more comprehensively. Additionally, it allowed researchers to assess the impact of time and external factors on the variables of interest, contributing to a deeper and more nuanced interpretation of the findings.

Regarding data analysis, the interviews were transcribed, and their content was systematically analysed following Bardin's (2016) guidelines, which consist of three main phases: 1) Pre-analysis: This phase involved organising the material to make it operational and systematised for further analysis; 2) Exploration of the material: During this phase, categories were defined (coding), and the registration and context units were identified within the documents; 3) Treatment of the results, inference, and interpretation. In this final phase, the information was condensed and highlighted for detailed analysis, culminating in inferential interpretations, which included moments of intuition, reflective insights, and critical analysis (Bardin, 2016). The categories were developed to encapsulate the essence of the innovation typology, reflecting the conceptions and implementations of the managers. This approach ensured the data analysis was rigorous and aligned with the study's objectives.

Initially, we used IRAMUTEQ to generate tables of word frequencies. This allowed us to describe absolute and relative frequencies, which were subsequently entered into an SPSS database. However, no statistically significant conclusions could be drawn, nor could more complex mathematical tests be performed, as the sample used in the study was not representative of the population (Pestana & Gageiro, 2014).

Despite these limitations, we found no evidence of significant differences between the variables analysed. Finally, the results were compared and contextualised with the existing literature to provide deeper insights and validation.

4. Results and discussion

4.1 Profile of participants and enquired companies

Women constitute the majority of workers in the tourism industry, particularly in the Global South and the informal sector (Kalisch & Cole, 2023). In Brazil, women represent a significant portion of the population and play a vital role in the tourism sector, occupying a wide variety of roles, including many that were once considered exclusively male. Despite their substantial presence in providing tourism services-especially in back-office positions-they remain underrepresented in leadership roles within the sector, a trend observed across Latin America, including Brazil.

The city of Natal-RN, however, presents a notable exception to this trend. It is the Brazilian capital with the most equitable distribution of leadership roles between men and women in municipal secretariats, according to a survey conducted and published by Folha de São Paulo (Prefeitura do Natal, 2024). Currently, 55.6% of these secretariats are headed by women. Of the 23 bodies within the direct, indirect, autarchic, and foundational administration, 12 are led by women, including the Municipal Tourism Secretariat (Prefeitura do Natal, 2024). This data highlights a unique aspect of the local context and aligns with our empirical findings, reflecting a more inclusive leadership dynamic in Natal.

The companies surveyed are predominantly run by women, who comprise 76% of the respondents. Women were observed not only in management positions but also as collaborators across multiple roles in all business categories. Regarding age, most managers (43%) are between 41 and 50, with 43 being the most frequently reported age. Overall, there was minimal variance in age distribution across the different business branches. A significant proportion of managers (31%) reported between 30 and 40 years of professional experience. The length of managerial experience correlated closely with age, as 35% of the older managers, those over 55, reported similarly extensive professional backgrounds. Regarding education, most managers stated they had completed higher education, with a strong concentration in management and tourism.

Regarding business size, most of the companies surveyed are small businesses. Among them, 15 (43%) are micro-enterprises with up to 9 employees, while 10 companies (approximately 28%) employ between 10 and 49 people. Over 70% of these businesses are family-owned, characterised by an overlap between ownership and control, which resides within the family. The competitive advantages of these family-owned businesses are often rooted in their tradition and family values, which foster a sense of identity and trust among customers. Key values highlighted in the interviews included loyalty, empathy, reliability, social responsibility, connectedness, and positive relational qualities such as customer orientation. In Natal, older family businesses were particularly recognised by interviewees as authentic hosts that embody the destination's identity and history. These businesses face the challenge of transmitting their heritage to employees, customers, and other stakeholders while balancing tradition with modernity. These findings align with Pikkemaat et al.'s (2019) and Schönherr et al. (2023) predictions, reinforcing the significance of family- owned enterprises in fostering a unique and authentic customer experience.

Most companies analysed (28 cases, or 80%) across all sectors had a trademark registered with the National Institute of Industrial Property (INPI). This percentage was even higher in specific sectors such as hotels, restaurants, cultural service providers, and travel agencies, where approximately 71% of companies had trademarks. At least one travel agency and one car rental company operated under a franchise model. Additionally, patent registrations were identified in several enterprises: 2 car rental companies, 1 museum, 1 water park, 4 hotels, 2 event venues that commercialise handcrafted products, 3 travel agencies, and 4 restaurants. Altogether, 43% of the analysed businesses secured copyrights for their patented innovations. These findings corroborate the observations of Camisón and Monfort-Mir (2012) and Omerzel and Jurdana (2016), who noted that while patents exist in tourism enterprises, they are not the most common innovation indicators. This is primarily due to the nature of tourism innovations, which are often difficult to protect and more prone to imitation (Camisón & Monfort-Mir, 2012; Omerzel & Jurdana, 2016).

All interviewees reported adopting a democratic and interactive attitude and being open to suggestions for improvement from stakeholders, particularly customers and employees. These claims were substantiated by presenting records, such as photos and videos, and documenting internal meetings with employees during the face-to-face interviews. They were further confirmed by observing and analysing comments and feedback addressed to customers on the companies' websites and social media platforms.

A consistent and unanimous theme across the interviews was the implementation of significant improvements and innovations in response to the pressures, needs, or desires expressed by consumers and employees. Managers provided examples of innovations stemming from various sources, including monitoring or interacting with competitors (80% of cases), acquiring knowledge through participation in events (80% of cases), and incorporating suggestions from partners and suppliers (68.6% of cases).

The managers interviewed unanimously acknowledged that selecting and retaining qualified and motivated employees is one of the most effective and important strategies for driving innovation (Panfiluk, 2021). This strategy entails addressing the challenge of creating and maintaining mechanisms to capture, select, and effectively utilise information circulating both within and outside the organisation (Omerzel & Jurdana, 2016; Pikkemaat et al., 2019; Schönherr et al., 2023). Managers reported taking deliberate actions to collect improvement suggestions from employees, often fostering teamwork to encourage collaboration. In 28 cases, formal (documented) procedures were in place to capture employee suggestions, and regular training programmes were provided to ensure employees were well-equipped to contribute effectively.

Table 2 categorically illustrates the grouping of the companies and provides the number of companies included in each group, offering further insights into these practices.

Table 2 Integration in groups and the total number of companies reached by specific activity

| Tourism activities | Integration in corporate groups | Total managers interviewed | Total companies reached | |

| No | Yes | |||

| Hospitality | 1 | 4 | 5 | 12 |

| Restaurants | 0 | 5 | 5 | 18 |

| Passenger transportation and rent-a-car | 2 | 3 | 5 | 17 |

| Cultural services | 2 | 3 | 5 | 9 |

| Trade, Events and Tourism Retail | 1 | 4 | 5 | 41 |

| Travel agencies | 1 | 4 | 5 | 14 |

| Recreation and leisure | 1 | 4 | 5 | 12 |

| Total | 8 | 27 | 35 | 123 |

Source: Own elaboration.

Most business managers-27 cases, or 77% of the participants-are part of corporate groups, with their primary activities situated within the tourism chain. Among these, a small proportion (less than 20%) operated under a franchise model.

Consistent with the observations of Booyens and Rogerson (2016) and Camisón and Monfort-Mir (2012), the dynamism of the tourism sector is evident in its capacity to reach new and diverse consumer markets. This represents one of the many opportunities for innovation within the sector. Regardless of company size, tourism businesses tend to invest in and launch their brands, effectively attracting new customer profiles across local, regional, national, and international markets.

4.2 Alignment between the concept and the implementation of innovation

Nuanced interpretations surround the concept and relevance of innovation in tourism enterprises. From the perspective of the interviewed managers, many of the reported innovation concepts inherently justified their rationale and existence. Synthesised expressions were developed to encapsulate the essence of innovation based on the interpretation and analysis of overlapping or closely related terms frequently appearing in the reports. The primary characteristic of innovation is the introduction of significant, marketable changes (OECD, 2005; Schumpeter, 1934). Notably, the meaning of innovation is often contextualised either as a tangible result or as the very performance and adaptability of companies to market stimuli. In this sense, innovation becomes essential for survival and growth in the tourism sector (Camisón & Monfort-Mir, 2012).

In line with innovation concepts found in the literature, the managers' perspectives tie the meaning of innovation to ideas such as renewal, significant improvements, necessary reconfigurations (physical, relational, or virtual), interactions, and knowledge (acquired, learned, shared, and/or imitated). Innovation is also associated with sensitivity and the ability to satisfy needs, solve problems, and add value. From the managers' responses, synonyms for innovation emerged, represented by terms such as the art of researching, discovering, developing, exploring, continuously improving, renewing, reinventing, reconfiguring, updating, recognising potential, and transforming identified problems and needs into sustainable market opportunities. These views align with the findings of Pazini (2015), Rodrigues and Anjos (2016), and Schönherr et al. (2023). In line with the literature, our results indicate that managers across all branches of tourism companies construct the meaning of innovation through everyday experiences and exchanges. This continuous learning process contributes non-linearly to enhancing the company's dynamic capabilities throughout the articulated innovation process. Their understanding of innovation not only influences other players in the business ecosystem but also shapes their intuition, which is reflected in the strategies they implement and the results they achieve. The study also found that innovation carries a universally positive connotation regardless of the company's size, legal nature, branch, period of activity, or whether it is part of a business group. Entrepreneurs consistently view it as fundamental for market survival. The advent of the pandemic and the acceleration of digital transformation have further reinforced this perception, reaffirming the critical role of innovation for competitiveness without altering its underlying meaning.

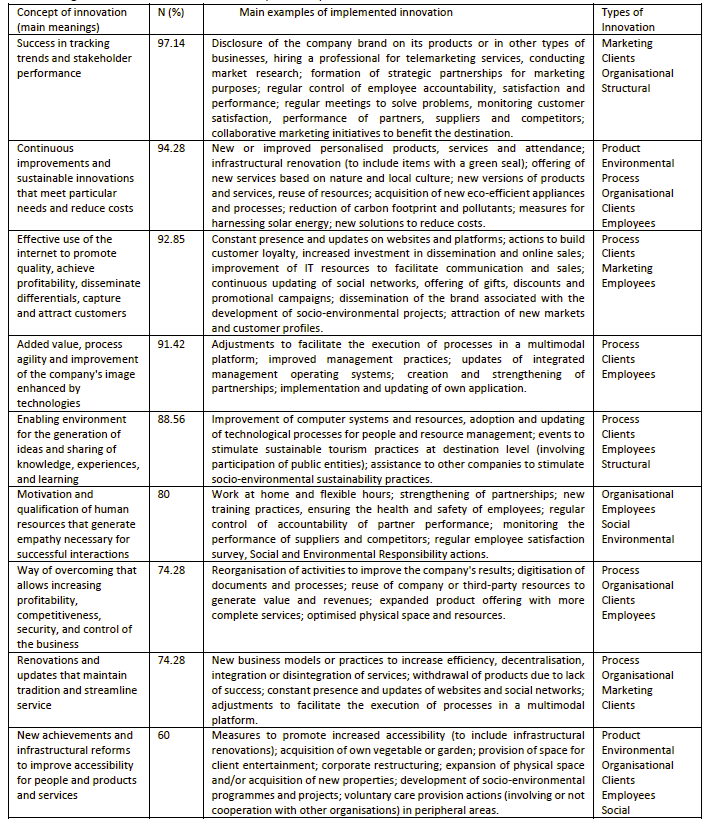

Table 3 provides insights into how much the innovation concept aligns with its practical implementation, offering a valuable framework for analysis.

Table 3 summarises the core meanings of innovation and juxtaposes them with examples of innovative actions implemented in tourism enterprises, as perceived by the interviewed managers. The concepts often intersect and overlap, reflecting their interconnected nature. Similarly, examples of implemented innovations frequently encompassed multiple types of innovation, aligning with findings by Bachmann and Destefani (2008) and Omerzel (2016). It was not uncommon for different terms to repeatedly evoke recurring conceptions and practices. Consistent with the expressed meanings, the innovation dynamics implemented in the companies aligned with an expanded innovation typology. This typology goes beyond the service innovations proposed in the Oslo Manual (OECD, 2005) and includes categories such as product, environmental, process, marketing, organisational, Customer, Employee, social, and structural innovations.

The coherence between the conceptions and practices of innovation was confirmed through a detailed analysis of the responses from the 35 interviewees. Key meanings were synthesised and ranked in descending order of average frequencies (in %) to analyse and verify their practical implementation. The findings were as follows: 1) Success in following trends and stakeholder performance: On average, reported by 97% of participants and confirmed in 80% of cases; 2) Continuous improvements and/or sustainable innovations that satisfy specific needs and reduce costs: On average, reported by 94% and confirmed in 91% of cases; 3) Effective use of the internet for quality promotion, profitability, showcasing differentials, and customer acquisition: On average, reported by 93% and confirmed in 92% of cases; 4) Value addition, process acceleration, and enhancement of company image through technologies: On average, reported by 91% and confirmed in 92% of cases; 5) Creation of a favorable environment for idea generation, knowledge sharing, and experiential learning: On average, reported by 88% and confirmed in 90% of cases; 6) Motivation and qualification of human resources, fostering empathy essential for successful interactions: On average, reported by 80% and confirmed in 90% of cases; 7) Overcoming challenges to increase profitability, competitiveness, security, and business control: On average, reported by 74% and confirmed in 86% of cases; 8) Renovations and updates that preserve tradition while streamlining services: On average, reported by 74% and confirmed in 86% of cases; 9) Infrastructure reforms to improve accessibility to products and services: On average, reported by 64% and confirmed in 92% of cases.

Although the average frequencies representing the concept and implementation of innovation were not identical in any of the cases, they were not so divergent as to be considered mismatched. The results revealed situations where managers conceptualise innovation beyond what they implement. However, the opposite was observed in most cases-managers operationalised innovation to a greater extent than initially conceived.

In line with the assumptions of Camisón and Monfort-Mir (2012) and Verreynne et al. (2019), the hypothesis that a disconnect exists between the concept and implementation of innovation could only be validated if most interviewees had conceived innovation in its broadest sense but in practice, restricted it to one or more specific types. However, as demonstrated in our investigation, this was not the case. On the contrary, the meanings and practices of innovation observed were consistent with key definitions in the literature. They reflected the specific characteristics of tourism enterprises while encompassing various innovation types.

Implementing novelties or improvements inevitably involves and impacts various stakeholders interested in the business-people, resources, and organisations. These stakeholders, whether interacting directly or indirectly, express their interests with the aim of satisfying their needs. In doing so, they influence, and are influenced by, the ways companies think, operate, and act.

The dynamics of these interactions are characterised by mutuality and reciprocity, standing in stark contrast to passive engagement. This logic remains unchanged during and after the pandemic; it has been further reinforced by intensified efforts to redirect strategies and develop solutions, many of which were already in place.

The interviewees unanimously recognised the COVID-19 pandemic as the most severe, prolonged, and complex crisis they had ever faced, aligning with the findings of recent literature (e.g., Abou-Shouk et al., 2023; Barrantes-Aguilar et al., 2023; Erul et al., 2023; Ruppenthal & Rückert-John, 2024; Silva-Oliveira & Avelar, 2024; Strouhal et al., 2024). Most respondents reported altering how they offer and promote their products and services, changing form, content, logistics, and delivery processes.

Simultaneously, reliance on technological resources and artificial intelligence across all branches of tourism increased significantly, consistent with observations by Buitrago-Esquinas et al. (2024). During the pandemic, companies, consumers, and society were inundated with vast amounts of information. Consequently, managers recognised the need to effectively use this information to generate knowledge that could create competitive advantages.

One common solution adopted by the companies was investing in the personalisation of products and services. Additionally, the significance of consumer experience reports regarding these products and services grew substantially. Regardless of size or sector, tourism businesses acknowledged the critical role of technology and digital transformation in advancing sustainability and fostering organisational and destination progress.

Developing or enhancing live e-commerce tools, using live broadcasts on social networks, and leveraging social media to advertise or sell goods and services while strengthening customer relationships were among companies' most widely implemented innovations, particularly during the pandemic. Many effects of the COVID-19 pandemic remain incalculable, and the full recovery of tourism businesses-mirroring global trends-continues to be an uncertainty for managers. This uncertainty is often built on hopes, speculative extrapolations, and interpretations that frequently lack scientific rigour.

In summary, the essence of innovation in a tourism company is reflected as a response or reaction to a range of pressures exerted on and experienced by the organisation. Companies think, feel, and act based on the stimuli they perceive. There are no universal rules or clearly defined limits to precisely determine which and how many stakeholders can influence or impact the activity and dynamism of a tourism company. This inherent complexity underscores the difficulty in solidifying, generalising, and universalising concepts, typologies, and tools for assessing the dynamics of innovation in tourism businesses. Researchers have endeavoured to address this challenge through persistent attempts to establish consensus and generalise what are often localised particularities. By its nature, tourism is a sector whose components and dynamics are characterised by boundaries so tenuous that they can be broken and redefined. This flexibility is fundamental, as the sector thrives on continuous movement and is sustained by new, inexhaustible, and infinite opportunities for dialogue and growth. In pursuing economic progress and its consolidation as a field of knowledge, tourism remains ever-adaptive and open to expansion.

5.2 Main conclusions

The objective of this article has been achieved by assessing how the (mis)match between innovation as conceived and as implemented occurs within tourism companies. The study emphasised the significance of localised particularities-such as the profiles and generational characteristics of entrepreneurs and managers, as well as the management structures of the companies- in shaping the dynamics and typologies of business innovation prevalent in the Natal destination. These findings were contextualised through a comparison with the theoretical framework and widely recognised global insights on innovation.

As a case study characterised by descriptive, exploratory, and applied research, this study was grounded in the interpretive paradigm. It focused on the participants' language, expression, and understanding and the observation of both face-to-face and virtual dynamics within their companies. Standardised interview protocols were adapted to ensure consistency and comparability across participants' responses. To maintain uniformity in interview style, relationship-building, and data collection procedures, a single researcher conducted all 35 face-to-face interviews. This deliberate choice minimised potential variations and ensured the reliability of the collected data.

The survey revealed that most companies are led by women, who accounted for 76% of the respondents. Women were predominant in management roles and as employees across various functions in all business categories. In terms of size, most companies are small businesses, employing a maximum of nine people. Additionally, over 70% of the businesses investigated are family-run. These companies often derive their competitive advantage from their strong roots in tradition and family values, which foster a sense of identity and trust among their customers. Key values highlighted during the interviews included loyalty, empathy, reliability, social responsibility, connection, and positive attributes such as relational qualities and customer orientation, further reinforcing their appeal and differentiation in the market.

The empirical research enabled us to diagnose the nature of innovation in tourism companies, which was predominantly incremental and easy to imitate. This finding highlights the unique characteristics of the tourism sector, which is defined by fuzzy boundaries and an interconnected network of companies spanning various branches of activity, locations, relationships, and strategies. Entrepreneurs in this sector continuously adapt and reconfigure their resources, efforts, and approaches to meet demand's diverse spatial and temporal contexts. This adaptability has fueled a promising market centred on consuming experiences, co-creation, and shared values. The dynamics of innovation in the tourism sector are influenced by many objective and subjective factors, presenting endless opportunities for dialogue and expansion in both conceptual and practical terms.

The main findings of this study suggest that the meanings attributed to tourism business innovation are consistent with those observed in other contexts in previous research. These meanings, which involve subjectivities blending the concept and foundation of innovation, align with the classic literature. Innovation, whether regarded as an outcome or as the performance, resilience, and responsiveness of companies, is shaped by the types and forms of its implementation. Its meaning encompasses actions such as investigating, discovering, developing, improving, and making things acceptable or marketable, along with the methods for achieving these goals. Regardless of the managers' and companies' profiles or the branch of activity (sub-sector), entrepreneurs universally view innovation as positive and essential for survival and competitiveness in the market. Innovation is driven by knowledge and learning, continuously evolving at its core.

The meanings of intra-sector innovation presented in this study were closely tied to renewal, significant improvements, reconfigurations, interactions, and knowledge-whether acquired, learned, shared, or imitated. They also encompassed sustainable strategies from environmental, social, and economic perspectives, monitoring trends, solving problems, fostering empathy, co-creating value, and meeting stakeholder needs. In alignment with these meanings, the innovation dynamics implemented by the companies focused on a typology of tourism innovation that extends beyond the Services typology proposed in the Oslo Manual (OECD, 2005). This broader framework includes product, environmental, process, marketing, organisational, Customer, Employee, social, and structural innovations.

This allows us to assert that these findings can serve as a starting point for uncovering other hidden particularities within the tourism sector and for comparing inter-context similarities and differences. Whether as an ideal or a practice, tourism business innovation is reaffirmed as a socially and interactively constructed phenomenon. It is subject to open rules, engagement, individual and collective creativity, the capacity to feel or evoke emotions, and, ultimately, understanding. All of this inherently involves a degree of risk and uncertainty, which is the essence and driving force behind the dynamics of change.

The conceptions of managers, as individual perspectives, extend beyond organisational boundaries to encompass structures, interactions with stakeholders, and the broader system-comprising interconnected subsystems-where innovation is inherent. As key players, these entrepreneurs influence and are influenced by the collective dynamics around them. While the concept and implementation of innovation in tourism companies are partially aligned in this reciprocal process, a predominant mismatch emerges. Most entrepreneurs in the sector operationalise innovation to a greater extent than they conceptualise it. This logic remains unchanged during and after the pandemic; it is further reinforced by intensified efforts to redirect strategies and implement solutions, many of which were already in place.

Managers across all branches of tourism companies construct meanings through everyday experiences and exchanges, engaging in continuous learning that contributes non-linearly to enhancing their companies' dynamic capabilities throughout the innovation process. Their understanding not only influences other players in the business ecosystem but also shapes their intuition, which is reflected in the strategies they implement and the results they achieve. The study found that innovation carries a universally positive connotation regardless of company size, legal nature, branch, period of activity, or affiliation with a business group. Entrepreneurs consistently view it as essential for survival in the market. The advent of the pandemic and the acceleration of digital transformation have further reinforced and reaffirmed this need-sine qua non for competitiveness-without fundamentally altering the meaning of innovation.

Most managers had to adapt how they offer and promote products and services, changing their form, content, logistics, and delivery. To optimise these adaptations, reliance on technological resources and artificial intelligence increased across all branches of tourism activity. Companies, consumers, and society were inundated with vast information during the pandemic. This led managers to recognise the need to utilise consumer and societal data effectively to generate actionable knowledge that could provide competitive advantages. One of the most frequently adopted solutions by the companies investigated was investing in personalising products and services. Additionally, the importance of consumer experience reports for these products and services grew significantly. Regardless of their size or branch of activity, tourism businesses increasingly recognise the critical role of technology and digital transformation in fostering sustainability, organisational growth, and destination progress.

During the pandemic, companies widely adopted innovations such as developing or enhancing live e-commerce tools, utilising live broadcasts on social networks, leveraging social media for advertising or selling products and services, and fostering stronger customer connections. The long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic remain difficult to quantify, and the full recovery of tourism businesses, mirroring trends seen globally, presents significant uncertainty for managers. This uncertainty is often based on optimism, speculative assumptions, and interpretations that frequently lack scientific rigour.

5.2. Theoretical and practical contributions

Investigations in innovation rarely encompass all branches of activity within the tourism sector. This study stands as one of the few exceptions. Another distinguishing feature is the field approach, which involved collecting data, revisiting, and monitoring the innovation dynamics of 35 companies over different periods-before, during, and after the pandemic-constituting a longitudinal study. This approach offered the opportunity to analyse changes within the same companies over time, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the research topic. Both the conception and implementation of innovation at the company level were examined in the context of the pandemic and the accelerated digital transformation, yielding valuable insights to inform and redirect future studies on the dynamics of innovation in tourism.

This research fostered meaningful dialogues with participating managers, enabling mutually beneficial learning exchanges. These interactions helped to raise awareness and sensitise managers, encouraging them to continuously rethink and align the meanings of innovation with its practical implementation in tourism. Theoretical and practical reflections emerging from this study are indispensable for guiding the effective management of business innovation in the sector. In the medium and long term, these insights can contribute to the development and refinement of policies, the (re)definition of indicators, and the creation of instruments for more effective intersectoral assessments. Such assessments would consider perspectives from the individual to the interactive, structural, and systemic. This study's temporal dimension and longitudinal design stand out as unique features, offering a foundation for future exploration and development of robust tools to measure and evaluate innovation in tourism businesses.

Researchers may explore tourism organisations in other contexts to uncover new concepts and perspectives, building on the findings discussed in this study. The methods, techniques, and content presented here are replicable, offering a foundation for further investigation. Highlighting the Natal context provides an opportunity to bring greater visibility to this destination within society and academia. Such visibility can facilitate targeted interventions to solve problems or develop strategies to enhance Natal's competitive advantage on regional, national, and international scales.

5.3 Limitations and suggestions for future research

The target audience and the limited number of interviews represent some of this study's main limitations. Expanding the strategy to include other stakeholders-such as back-office and front-office employees, clients, and governmental organisations-would have been valuable. Additionally, designing and applying surveys distributed electronically could have reached a larger, more representative population sample. This approach would also allow for comparing the effectiveness, quality of responses, and timeliness of return rates between interviews and surveys. The use of focus groups also appears pertinent and compatible with objectives similar to ours. Implementing this technique in the investigated context might have yielded more relevant and generalisable results in a shorter period. Furthermore, many companies could have been followed more systematically through social networks. For example, Facebook pages were monitored before and after interviews to confirm or update information, providing additional evidence to enrich observations. However, this was not done for all cases, and the search process, while methodical, was more intuitive than systematised.

It is important to note that part of the results aimed to understand and justify the frequency of analysis categories. While this approach is valid, it is somewhat limited regarding the depth of results and validation. A more comprehensive exploration of the implications of these frequencies would be crucial. Establishing a correlation between the implementation and the conceptual elements underlying the congruence or divergence between these factors could yield richer and more insightful results.

This research was conducted in Brazil, a country of continental dimensions. However, the spatial focus was limited to Natal. Expanding studies to other locations within or outside the country would be necessary to facilitate comparisons and enrich the body of knowledge on the subject. Given the dynamic nature of innovation meanings and practices within their historical and temporal contexts, future research could further investigate the intrinsic relationship between time, conceptualisation, innovation implementation, and entrepreneurial behaviour in tourism.

New contributions could complement our findings by addressing questions such as: What are the main barriers to implementing innovation in tourism firms? What measures have been or could be adopted to overcome these challenges?

Finally, we recommend developing conceptual models and reference instruments to enhance the effective management, evaluation, and measurement of business innovation in tourism.

Credit author statement

Conceptualisation, J.A., C.C.. and F.B.; data collection: J.A.; data curation, J.A., CC.; formal analysis, J.A., C.C.. and F.B.; supervision, C.C.. and F.B.; writing-original draft, J.A., C.C., F.B., and L.C.S.F.; writing-review and editing, J.A., C.C. F.B., and L.C.S.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.