Introduction

Benign metastasizing leiomyoma (BML) is a very uncommon condition, first described by Steiner in 1939,1 characterized by well-differentiated leiomyomas at sites distant from the uterus, representing a rare form of a histological benign tumor with metastasizing behavior.2,3 BML is usually seen in women of reproductive age presenting a history of uterine leiomyoma who underwent hysterectomy, which supports the hematogenous and iatrogenic spread of the tumor.2,3 However, there have been more uncommon cases of BML lung nodules detected even before hysterectomy3,5 as reported in our clinical case. Most pulmonary BMLs are diagnosed incidentally, as most patients are asymptomatic and present multiple, well-circumscribed lung nodules upon imaging study.3,4,6

Case Report

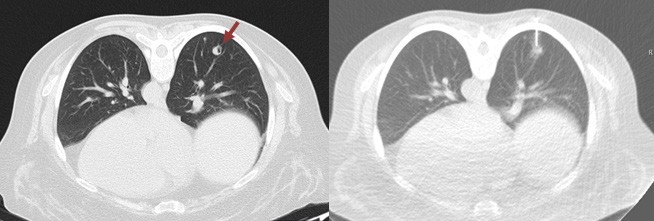

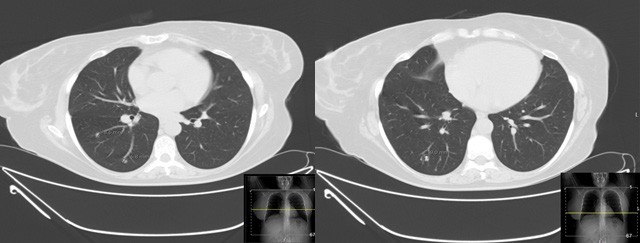

We present a case of a 47-year-old non-smoker, non- drinking Caucasian woman recently diagnosed with invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue (cT2N0Mx). A decision was made to perform right hemiglossectomy with tumor exeresis and radical cervical lymphadenectomy. CT scan of the head, neck and chest were also performed for cancer staging. High resolution CT scan revealed three round subpleural nodules of uncertain etiology, located posterior and inferiorly in the right upper lobe and superiorly in the right lower lobe, measuring 6.8, 8.6 and 9 mm, the latter presenting cavitation. (Figure 1). No hilar or mediastinic lymphadenopathies were observed, and there were no pleural or pericardial effusions. No other remarkable changes were seen in the mediastinum or the lungs. The patient remained asymptomatic. CT guided transthoracic biopsy was required for nodule characterization, and biopsy of the 9 mm cavitary lung nodule (Figure 2) revealed pulmonary parenchyma with mostly preserved alveolar structure, partially occupied by spindle cell proliferation, without pleomorphism, necrotic areas, atypia or mitotic figures.

Figure 1: Axial chest CT scan showing three round subpleural nodules of uncertain etiology, located posterior and inferiorly in the right upper lobe and superiorly in the right lower lobe, measuring 6.8, 8.6 and 9 mm, the latter presenting cavitation.

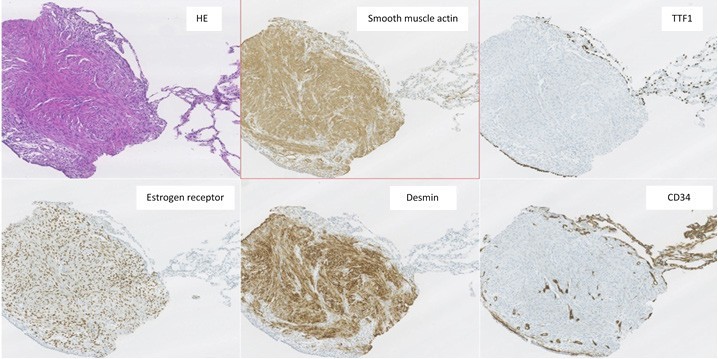

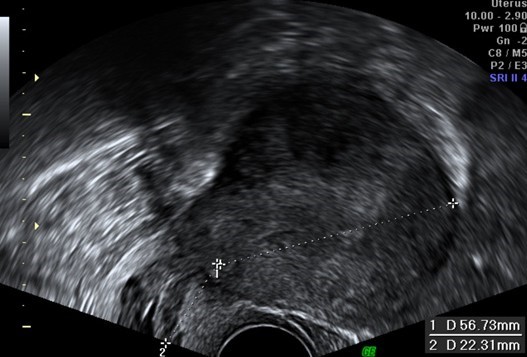

Immunohistochemical staining showed positivity for smooth-muscle actin, desmin and estrogen and progesterone receptors, while showing negativity for TTF1, AE1/AE3, bcl2 and CD34. The histological findings were compatible with BML (Figure 3). Due to these findings, the patient (who had no clinical history of known leiomyomas or other gynecological conditions) was referred to gynecological consultation and transvaginal ultrasound examination revealed a heterogeneous uterine wall with two intramural hypoechoic lesions (measuring 12 x 12 mm and 10 x 6 mm) and one subserosal hypoechoic lesion (measuring 54 x 28 mm), suggestive of uterine leiomyomas (Figure 4). The patient underwent hysterectomy and bilateral adnexectomy, and surgical histopathological study confirmed the diagnosis of multiple uterine leiomyomas, confirming the origin of the BML lesions found in the lungs. The latest postoperative CT chest scan for lung nodules evaluation showed overlapping characteristics, compared to previous imaging studies. As such, these BML lesions remain morphologically and numerically stable. The patient remained asymptomatic and was followed- up in consultation. No surgical or hormonal therapy was performed in regard to BML, and a CT chest scan was scheduled 6 months later to monitor the lesions.

Figure 3: Pathological findings of transthoracic lung biopsy of the 9 mm cavitary nodule revealed, by H&E staining, pulmonary parenchyma with mostly preserved alveolar structure, partially occupied by spindle smooth cell proliferation, without pleomorphism, necrotic areas, atypia or mitotic figures. Immunohistochemical staining showed positivity for smooth-muscle actin, desmin and estrogen and progesterone receptors, while showing negativity for TTF1, AE1/AE3, bcl2 and CD34. These histological findings were compatible with BML.

Figure 4: Transvaginal ultrasound examination revealed a heterogeneous uterine wall with two intramural hypoechoic lesions (measuring 12 x 12 mm and 10 x 6 mm) and one subserosal hypoechoic lesion (measuring 54 x 28 mm), suggestive of uterine leiomyomas. Surgical histopathological study later confirmed this diagnosis.

Discussion

BML is a rare entity, with few more than 120 cases described in the literature.2,3 This uncommon condition presents itself with well-differentiated leiomyomas at sites distant from the uterus. The pathogenesis of BML has remained controversial, with different proposed etiologies: hematogenous spread of benign uterine tumor; metastatic low grade leiomyosarcoma; or smooth muscle proliferation in response to hormonal stimulation.3,4 The most common sites for metastasis are the lungs,2,3,8 but extrapulmonary lesions have also been documented, including the lymph nodes, peritoneum, bones, skin, inferior vena cava, brain and heart.4,6 A previous history of hysterectomy for uterine leiomyoma may be indicative of this condition,3,8 and the reported time interval between hysterectomy and the detection of lung nodules can range up to 20 years, according to the literature.2 However, BML has also been identified in men2 and in patients with lung nodules and no history of uterine fibroids.2,3

Imaging features of BML are non-specific.2 Lung involvement in BML may appear as lung nodules on chest radiography or CT, ranging from solitary sub-centimetric lesions to multiple lesions similar to malignant metastases.2,8 The usual presentation is the presence of bilateral, well-circumscribed, non-calcified nodules diagnosed incidentally.2,3 Cavitation of these lesions may occur,2,3 as in our clinical case. More rarely, pneumothorax may take place, along with occasional cases of miliary pattern and pattern simulating interstitial disease.2 CT and MR imaging studies are often used to detect and describe these pulmonary nodules, which usually present homogeneous enhancement and non-specific appearance.2 As such, a list of differential diagnosis must be taken into account when considering possible BML lung nodules, including lung malignant metastases and, more rarely, infectious pulmonary granulomas, rheumatoid nodules, sarcoidosis and amyloidosis.2 In this clinical case, given the previous oncologic diagnosis and no known history of uterine leiomyomas, our main concern was to rule out malignant nature of these lung nodules, due to the possibility of distant metastases of oral squamous cell carcinoma.9,10 Imaging-guided biopsy is most often required to get a definitive diagnosis.

While most patients remain asymptomatic, symptoms like cough, dyspnea, hemoptysis or chest pain have been described in a few cases.3,4,7 Because it’s a rare entity, there are currently no guidelines for the treatment of BML, and clinical decision ranges from patient observation to surgical resection or hormonal therapy (selective estrogen receptor modulator, progesterone, aromatase inhibitors, oophorectomy and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues).3 The latter therapeutic option is based on the positivity for estrogen and progesterone receptors found in these lesions. This positivity, along with studies showing a monoclonal common origin of both the lung and uterine tumors,3 further supports the hypothesis of hematogenous spread of a benign tumor arising from the uterine smooth muscle.3,4 The clinical course of BML is usually indolent, with cases of spontaneous resolution of BML already described.2 However, progression of the pulmonary lesions may occur, leading to pulmonary insufficiency and eventually, death.2,3 In this clinical case, because the patient remained asymptomatic, imaging surveillance of the lesions was preferred.

In conclusion, BML is a peculiar entity that displays benign histological features along with metastasizing behavior. Despite its rarity, BML should be considered in the differential diagnosis in asymptomatic middle-aged women usually with a history of hysterectomy and/or uterine leiomyomas, who present solitary or multiple lung nodules. As further proved by our example in this article, this is not always the case, and the patient could present lung BML nodules even before hysterectomy or the diagnosis of uterine fibroids. It’s also an entity that should be kept in mind when evaluating the etiology of lung nodules, particularly when trying to rule out malignant metastases.