Introduction

Urachal carcinoma is a rare neoplasm that accounts for 0.01% of all adult cancers and 0.5%-2.0% of all bladder malignancies.(1,2) Firstly described by Hue and Jacquin in 1863, urachal carcinomas are more common in men between 20 and 90 years old, with a peak in the 50s.(1,3) Risk factors remain unclear.

Clinical manifestations include hematuria, abdominal pain, suprapubic mass, irritative voiding symptoms, and umbilical discharge.(4) However, due to their extraperitoneal location, these tumors may be initially clinically silent and only manifest at advanced stages due to mass-effect symptoms, local invasion or metastatic disease.(3,5) This diagnostic delay usually carries a poor prognosis.

The diagnostic evaluation for urachal carcinoma should include a careful history and physical examination. A urine analysis with cytology may be helpful as it can confirm hematuria or demonstrate the presence of atypical cells. However, urachal carcinoma is primarily an extravesical cancer, therefore hematuria and positive urine cytology only occur when the tumor has already invaded the mucosa. A cystoscopy is also recommended to evaluate if the lesion is covered with normal mucosa, as seen in early stages, or if it is an ulcerated mass due to the intramural spread.(2,6) The definitive diagnosis is histological.

Case Presentation

A 49-year-old woman was referred to our hospital with a history of recurrent pelvic discomfort for the previous 3-4 weeks. There were no urogenital symptoms or fever. Her medical history was unremarkable. On physical examination, a firm and non-tender midline, suprapubic mass was palpable. Laboratory test results were normal.

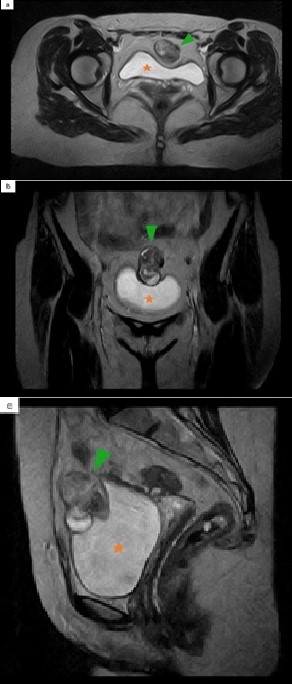

A pelvic ultrasound (US) revealed a 55-mm supravesical, midline, solid tumor (Figure 1). The lesion was heterogeneous, mainly hypoechoic, with some foci of increased echogenicity. Due to its better contrast resolution, a pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed, confirming the presence of a 55-mm midline, intra-abdominal, and infraumbilical solid tumor. The lesion showed heterogeneous signal intensity on T2- weighted images (WI) (Figure 2), with both hypo and hyperintense areas. On T1-WI, the lesion was isointense to the abdominal wall muscles and bladder wall.

Figure 1: Pelvic US revealing a 55-mm supravesical, midline, solid mass, mainly hypoechoic, with some foci of increased echogenicity. Green arrowhead: urachal adenocarcinoma. Orange star: bladder.

Figure 2: Pelvic MRI. Axial (a), coronal (b) and sagittal (c) T2- WI show a midline lobulated mass, with heterogeneous signal intensity. Green arrowhead: urachal adenocarcinoma. Orange star: bladder.

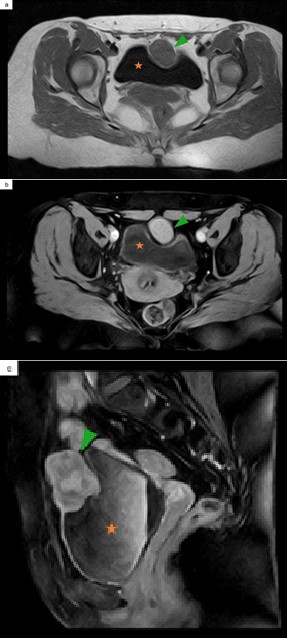

After gadolinium administration, it showed avid enhancement (Figure 3 a,b). Inferiorly, the tumor extended through the dome and anterosuperior wall of the bladder, with no fat interface in between, a highly suspicious feature of invasion (Figure 3 c). Anteriorly, it extended towards the abdominal wall, without signs of infiltration. There were also no signs of invasion of the peritoneal reflection. The characteristics of the mass and its location favored a urachal carcinoma as the main diagnosis. A chest, abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) revealed no regional or distant metastases.

The patient underwent a partial cystectomy with en bloc resection of the tumor, as well as the urachal remnant and the umbilicus. Bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection was also performed.

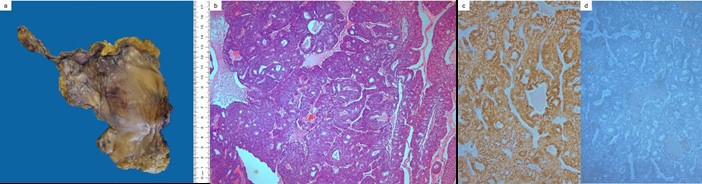

There was a 55-mm solid nodular lesion located in the dome, with a friable and grayish-white cut surface.

Figure 3: Pelvic MRI. Axial T1 pre-contrast (a) and FS T1 post-contrast (b) demonstrate an intermediate signal intensity lesion (a), with avid contrast enhancement (b). Sagittal FS T1 post-contrast (c) establishes the extension inferiorly through the dome and anterosuperior wall of the bladder. Green arrowhead: urachal adenocarcinoma. Orange star: bladder.

Histologic examination revealed a non-cystic enteric type urachal adenocarcinoma, which infiltrated the bladder wall with mucosa ulceration but spared the abdominal wall and peritoneum. The immunohistochemical profile was positive for CDX2 and CK20, while negative for p63 (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Photograph of the gross specimen (a). Microscopic pathology confirming non-cystic enteric urachal adenocarcinoma (H&E, 50x) (b), with most of the neoplastic cells expressing CDX2 (50x) (c) and no staining for p63 (50x) (d).

Surgical margins were negative and there were no lymph node metastases. These features favored a urachal adenocarcinoma on stage IIIA (local urachal cancer extension to the bladder), according to the Sheldon staging system.(1)

A colonoscopy was performed, and it was negative for primary colorectal cancer.

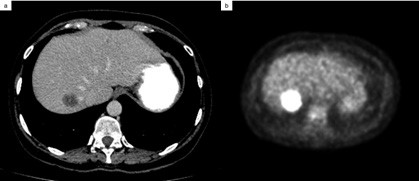

A follow-up contrast-enhanced CT scan performed 6-months after surgery revealed a hypoattenuating lesion in the right liver lobe with 25-mm in diameter that was considered suspicious (Figure 5 a). A subsequent 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography- computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) scan of the entire body confirmed the diagnosis of single liver metastasis (Figure 5 b).

Discussion / Conclusion

The urachus is a midline embryological ductal remnant of the fetal genitourinary tract that originates from the allantois and the cloaca, extending from the umbilicus to the dome of the bladder.(3) It usually involutes before birth to a fibrous band and becomes the median umbilical ligament.(4) It is located extraperitoneally, within the space of Retzius, surrounded anteriorly by the transversalis fascia and posteriorly by the peritoneum.(4)

Incomplete regression of the urachus may result in urachal remnants that have the potential to become infected or undergo malignant transformation.(3) Although it is normally lined by transitional epithelium, most urachal tumors are adenocarcinomas (90%). The pathogenesis of urachal adenocarcinomas is not fully understood.(1,3) Adenocarcinomas can be non-cystic or cystic. The majority are non-cystic adenocarcinomas that include mucinous type (50%), enteric type (24%), mixed type (10%), not otherwise specified type (9%), and signet ring cell type (7%).(7) Immunohistochemistry shows some overlap among these different subtypes. The urachal adenocarcinoma is generally positive for CDX2 and CK20. p63 is rarely positive so it is useful to distinguish from urothelial carcinoma with glandular differentiation.(7)

Imaging plays an important role in the workup of urachal tumors as it can depict the location, size and invasiveness of the mass. Despite the absence of specific imaging findings for urachal carcinomas, a midline supravesical mass, adjacent to the abdominal wall, either solid, cystic, or mixed, should always raise the suspicion for this diagnosis.(1,3,4,5)

US is often the initial imaging modality as it is a non-invasive and readily available procedure in most clinical settings. CT and MRI are useful for staging. However, MRI is superior to CT for assessing local bladder wall, abdominal wall and peritoneal involvement. A contrast-enhanced CT scan of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis is essential for evaluation of distant metastasis.(4,5) In patients with contraindication for iodinated contrast medium, whole-body MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging or 18F-FDG PET/CT can provide accurate information on staging.

On MRI, urachal adenocarcinoma usually shows high signal intensity on T2-WI, which is particularly true for the most typical mucinous type. Literature data is scarce regarding specific features of other types.

Although urachal carcinoma can occur in any site along the urachal tract, it typically arises close to the dome of the bladder, as in our case.(3) The main differential diagnoses

include benign urachal tumors, non-urachal carcinomas of the bladder, infected urachal remnant and metastasis from primary lesions of the colon, prostate or female genital tract.(4,5)

Our case fulfilled the diagnostic criteria stated in the last edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs, which are: 1. location of the tumor in the bladder dome and/or anterior wall; 2. epicenter of carcinoma in the bladder wall; 3. absence of widespread cystitis cystica and/or cystitis glandularis beyond the dome or anterior wall, and 4. absence of a known primary elsewhere.(7,8) The presence of urachal remnant in association with the tumor is supportive of the diagnosis. Several staging systems have been proposed for urachal carcinoma (Sheldon,(1) Mayo,(9) and Ontario(10)) with none formally validated (Table 1).(7)

Table 1 Urachal Carcinoma Staging Systems

| Sheldon1 79. | Mayo9 81. | Ontario10 83. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | No invasion beyond the urachal mucosa | I | Confined to the urachus and/or bladder | T1 | Confined to the submucosa |

| II | Invasion confined to the urachus itself | II | Extension beyond muscular layer of the urachus and/or the bladder | T2 | Confined to the bladder muscular wall |

| III | Local extension into: | III | Infiltration to the regional lymph nodes | T3 | Extension into the periurachal or vesical soft tissue |

| A - Bladder | |||||

| B - Abdominal wall | |||||

| C - Peritoneum | |||||

| D - Viscera other than bladder | |||||

| IV | Metastasis to: | IV | Infiltration to non-regional lymph nodes or other distant sites | T4 | Invasion to adjacent organs, including abdominal wall |

| A - Regional lymph nodes | |||||

| B - Distant sites | |||||

The most significant predictors of urachal adenocarcinoma prognosis are pathological tumor stage and surgical margins.(11) Regarding treatment, proper surgical intervention is critical. The standard surgical approach includes excision of the urachus and umbilicus combined with partial/radical cystectomy and bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy.(1,5,7,9) Currently, there is no definitive role for neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment.(2,5,9)