Introduction

Morbimortality associated with placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) disorders occur mostly during childbirth when trying to remove the placenta from the uterus, which can trigger massive obstetric hemorrhage.(1)

Timely delivery planning and management by an experienced multidisciplinary team have been shown to improve maternal and neonatal outcomes.(2) In tertiary- care centers, like ours, minimally invasive endovascular interventional radiology (IR) techniques performed before surgery have become an integral part of management on women affected by PAS disorders.(3,4) They have been shown to be effective in reducing estimated blood loss, transfusion requirements, and in providing favorable surgical conditions for the gynecology and obstetrics (GO) team (better hemostasis and field visibility). Literature data is, however, heterogeneous and most studies have poor quality.(4,5) The optimal positioning for occlusion balloon (OB) catheters is also controversial and protocols differ between institutions and local expertise. Our preference is for perioperative prophylactic balloon-occlusion of the hypogastric arteries (PBOHA).

The procedure was first done in our institution in 2015 and rarely performed until 2018. Since then, the GO and IR teams started working together in developing a protocol to optimize the response to these patients. A total of 10 cases with PAS disorder were submitted to PBOHA before planned cesarean delivery and all performed hysterectomy, except one. Although the protocol is at an initial stage, so far, outcomes have been positive, within literature references and no endovascular complications were registered.

Aiming to share our favorable experience, this report provides a detailed description of the technical aspects and materials used in our center for PBOHA, from the angio suite until completion of hysterectomy. For that, we use a case of a pathologically proven placenta increta as an example.

Case Report

A 42-year-old woman with placenta previa was admitted to our hospital at 25 weeks of gestation due to vaginal bleeding. This was the third ongoing pregnancy with two previous cesarean deliveries. Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging, at 28 and 30 weeks of gestation, respectively, showed complete placenta previa and positive findings for invasive placentation.

Surgical and perioperative multidisciplinary planning was done by GO, anesthesiology, IR, neonatology and imunohemotherapy teams. An elective cesarean was scheduled at 36 weeks with possible need for total hysterectomy. Due to the high risk of surgical bleeding, additional PBOHA was planned.

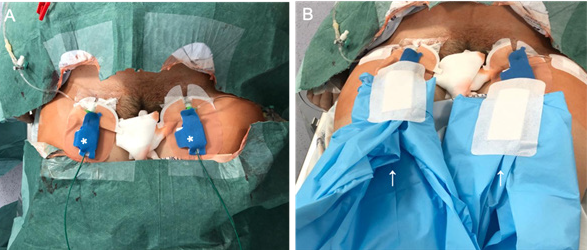

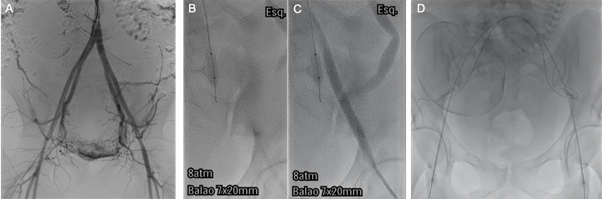

On the scheduled day, the patient went first to the angio suite for placement of OB in the hypogastric arteries (HA). Patient sedation and analgesia was managed by the anesthesiologists’ team. After local anesthesia (2% lidocaine), bilateral common femoral artery access was obtained, using 6F sheaths (Radifocus® Introducer II Guidewire-J Spring, 6 F, Terumo). Manual injection of contrast through one of the sheaths was used to delineate both HA anatomy and obtain a road map. An hydrophilic Cobra 2 catheter (Glidecath®, 5 F, 100 cm, Terumo) and an hydrophilic angled tip guidewire(Glidewire® Hydrophilic Coated Guidewire, 0,035”, 180 cm, Terumo) were used to select the contralateral HA. An OB (Advance® 7x20mm, 0.035”, 5 F, 80 cm, Biosonda- Cook) was then positioned over-the-wire, in the proximal portion of the HA, under intermittent fluoroscopic view; the road map was only used to confirm the final position of the balloon. After satisfactory positioning, the OB was tested by inflating, until nominal pressure was achieved, and, afterwards, deflated. The procedure was then repeated for the contralateral side. A final image was obtained with bone reference, to allow for balloon position confirmation in the operating room (Fig. 1). Total fluoroscopy time was 3.9 minutes, dose area product (DAP) was 28.215 Gy*cm2 and air kerma was 104 mGy. Lastly, guidewires were secured to the OB catheters by unidirectional hemostatic valves (Flo30TM, MeritMedical), sheaths were sutured to the skin, and both sheaths and OB catheters were securely fixed together using a SkaterTMFix (Argon); the whole material was then wrapped in two separate sterile fields before the patient was transferred to the operating room (Fig. 2).

Once the patient arrived at the operating room, a big sterile field was positioned under the IR material. The OB catheters were straightened along patients’ legs and attached to the inflation pumps, allowing the interventional radiologist to have rapid access from the bottom, without disturbing surgeons. Fluoroscopic confirmation of the OB position was done. The patient was then routinely prepared for cesarean section. At surgery, a bulging placenta in the anterior uterine wall was confirmed, although there were no signs of bladder invasion. Uterine incision was performed above the upper limit of the bulging placenta to avoid it. After fetal extraction, both OB were inflated to their nominal pressure. A gentle attempt to remove the placenta was unsuccessful, so it was left in situ. Hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy was performed and OB were inflated for 40 minutes. During deflation no active bleeding was seen by the surgeons. After surgical incision was closed, OB catheters were removed under fluoroscopic control and puncture sites were occluded with a vascular closure device (Exoseal®, 6 F, Cordis). During surgery, tranexamic acid and one pack of red blood cells were given. The total estimated blood loss was 900cc. The lowest value of hemoglobin was 8,9g/ dL and no further blood transfusions were needed. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit for hemodynamic monitoring in the early postoperative period. No complications were reported. The newborn boy was healthy, weighed 2540g and the APGAR score was 9 and 10 at the first and fifth minutes, respectively. The patient was discharged at the sixth day postpartum. Anatomopathological examination of the uterus showed loss of the decidual layer and deep invasion of the myometrium, less than 1 mm away of the serosa compatible with placenta increta.

Figure 1: Fluoroscopic images at the angio suite. A) Initial angiogram to delineate HA anatomy and road mapping guidance. B and C) Test inflation of the left occlusion balloon using diluted water-soluble contrast. Note that it is not possible to inject contrast to control the second balloon. D) Final image with bone reference, to guide balloon inflation in the operating room. Note the position of the guidewire in branches of the posterior division of the hypogastric artery.

Discussion

Planned cesarean hysterectomy, leaving the placenta in situ, is the general recommendation from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and remains the definitive surgical treatment for PAS disorders, especially for its invasive forms.(1,5) Minimally invasive IR techniques allow for preoperative placement of endovascular balloons to occlude the bloodstream proximally to the uterine arteries and promote a decrease in uterine arterial supply, after umbilical cord clamping. The main goal is to reduce hemorrhage; even when successful vessel occlusion is achieved, some blood loss is expected to occur.(5)

The endovascular approach in the angio suite is not long and has a low rate of adverse events;(4,7) nevertheless, the IR team has to be available to accompany the patient through the whole process. The placement of the OB is done by the two most experienced interventional radiologists, as well as a trained technician operating the angiography equipment, to minimize possible side effects. There is concern to minimize radiation to the fetus, using intermittent pulse and stored fluoroscopy (instead of acquisitions), with collimated images, no magnification and low pulse rates.(8,9,10) The optimal position of OB catheters placement is still controversial and heterogeneous results are found when reviewing the latest literature. Arterial occlusion upstream of the HA (at the common iliac arteries or infrarenal aorta) has the potential advantage of blocking vascular flow at the collateral pathways between the hypogastric and external iliac arteries. This is however counterbalanced by the potential risk of greater traumatic injury and ischemic damage of a larger vascular territory.(5,10) Although HA balloon occlusion does not prevent collateral flow from external iliac branch, the vascular territory at risk of perfusion injury is smaller and trauma is diminished by the use of smaller-caliber material. Though opinions and protocols may differ between institutions and local expertise, the latest systematic review and meta-analysis concerning this topic wasn’t able to demonstrate a meaningful comparison between different IR techniques, mainly due to the small sample size of most studies.(4) Our preference is for placement of the OB bilaterally in the proximal segment of the HA by contralateral femoral approach.

The size of the balloon should be optimally tailored to the vessel being occluded. The MRI done preoperatively is a useful tool to predict the size of the OB that will be needed in advance. We usually upgrade the diameter of the OB by 1-2 mm of the vessel caliber, bearing in mind that after delivery the size of the artery tends to increase slightly. Careful must be taken to never inflate both OB at the same time before delivery, as this would considerably decrease blood flow for the fetus. After childbirth, if necessary (when blood loss is higher than expected) we may additionally inflate the OB 1-2 mmHg above nominal pressure, to compensate for a slight increase of the artery caliber that can occur after delivery. As illustrated in this case, we routinely use 20mm Advance® 0.035”, Biosonda- Cook OB catheters of 7 mm, 8 mm or 9 mm of diameter, and we have been able to achieve maximal wall tension without vessel rupture.

During OB placement, the tips of the guidewires should preferentially be kept in the posterior division of the HA to avoid potential spasm of the anterior division and its uterine branch. The guidewires are kept inside the OB catheters to confer more stability to the latter and to allow for rapid repositioning of the OB in case they are dislodged.

Some centers leave the OB inflated after surgery, bearing in mind the increased risk of hemorrhagic complications in the following hours.(5,11) Similarly to other centers,(9,12,13,14) we deflate the OB after surgical procedure is finished OB (maximum OB inflation time in our experience was 60 minutes). Even though there is, once more, no consensus on this matter, our approach relates to safety concerns (lack of staff to tightly monitor possible complications). Thrombosis and reperfusion injury of the lower limbs, although uncommon, remain the main complications of the endovascular procedure).(5,11) Postoperative care includes absolute rest for 4 hours, avoidance of physical efforts for 48 hours, inguinal bandage surveillance for the first 12 hours and vital signs monitoring.

In conclusion, PBOHA should be considered as part of a multidisciplinary approach to reduce postpartum uterine hemorrhage in the setting of PAS disorders. It is a minimally invasive endovascular procedure, uncommonly associated with adverse events in experienced hands. It has been easily implemented in our center, and although it requires full availability from the IR team, it does not add a great deal of complexity to the surgical approach.