Introduction

Snakebite envenoming is a potentially life-threatening disease caused by toxins in the bite of a venomous snake. Furthermore, it is a neglected public health issue and a common medical emergency in many tropical countries.1 According to the World Health Organization, about 5.4 million snakebites occur each year, resulting in 1.8 to 2.7 million cases of envenomings (poisoning from snake bites). There are between 81,410 and 137,880 deaths and around three times as many amputations and other permanent disabilities each year secondary to these events.2 Tropical areas have the highest prevalence of venomous snakes, including Southeast Asia, Southwestern Europe, Sub- Saharan Africa, the United States of America and Latin America(Figure 1).3

The Viperidae family is responsible for most of the registered snakebite accidents in Latin America. In Brazil, the genus Bothrops is responsible for 85% of the ophidian envenomation.4 Bothropic venom has important physiopathological effects, with local lesions and tissue necrosis (proteolytic action). It also activates the coagulation cascade and promotes blood incoagulability through the consumption of fibrinogen, leading to hemorrhagic events by causing damage to the basal membrane of capillaries associated with thrombocytopenia (anticoagulant action). Moreover, bothropic venom promotes the release of hypotensive substances that, associated with the hemorrhagic manifestations, configure a life-threatening situation, which are frequent in this type of ophidian accident.5

Case Presentation

A 61-year-old man was bitten by a snake on his left thigh in Macaé, a city in the countryside of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and was taken to the emergency department of a tertiary hospital. The patient arrived with an estimated time of 5 hours after the ophidic accident and presented with hypotension, lethargy, with sphincter release, nausea and vomiting. Besides the edema at the site of the snakebite, several snakebite marks were noted in the left thigh. The number of bites raised the alert for the possibility of a large amount of venom inoculated, being a great predictor of severity.

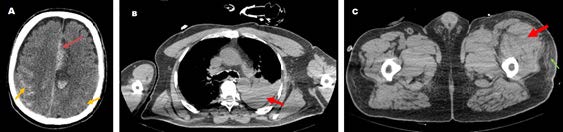

The snake was identified as the Bothrops atrox (common lancehead) by the patient’s relatives, who reported finding him unconscious, justifying the number of bites. A few minutes after admission to the hospital, he presented a generalized tonic-clonic seizure, with sphincter release, melena, hemoptysis and tachypnea, requiring orotracheal intubation and ventilatory support. On physical examination, the patient presented signs of circulatory shock, in addition to lethargy and abolished breath sound on chest auscultation in the left lung base. Computed tomography (CT) of the brain, chest, abdomen and pelvis were performed, and demonstrated intracerebral hemorrhage in the left frontal lobe, bilateral subarachnoid hemorrhage, moderate left hemothorax and soft tissue edema at the site of the snakebites on the left thigh (Figure 2).

His blood tests presented low platelet count (20.000 cells/ mm3), leukocytosis (17.480 cells/mm3), high creatine kinase (CK: 870 units per litre), elevated levels of international normalized ratio (INR: 3,5) and activated partial thromboplastin (aPTT: 80 seconds). Despite treatment with botropic antivenom being promptly instituted, along with all necessary clinical support measures, the patient suffered a cardiac arrest refractory to cardiopulmonary resuscitation measures, on the fourth day of hospitalization.

Figure 2: (A) Brain CT-scan without contrast showing intraparenchymal hemorrhage with perilesional edema in the left frontal lobe (red arrow) and bilateral subarachnoid hemorrhage (yellow arrows). (B) Axial nonenhanced chest CT (mediastinal window) presenting moderate left pleural effusion with high density (50 UH) compatible with hemothorax (red arrow). (C) Pelvic CT-scan without contrast demonstrating soft tissue edema with enlargement of the quadriceps muscles (red arrow) and densification of the subcutaneous adipose tissue (green arrow) at the site of the snakebite on the left thigh.

Discussion

This is a case of a patient developing severe coagulopathy disorder and clinical manifestations of cerebral hemorrhage and acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure after being bitten a few times by Bothrops atrox. Local manifestations of bothropic accidents include pain, edema, often associated with ecchymosis and local bleeding. Lymphadenopathy and blisters may appear in the process.3,5Systemic and life-threatening manifestations are hypotension, circulatory shock, acute kidney injury, and hemorrhagic events. Complications, although infrequent, are almost always fatal and difficult to manage and include abscess formation, necrosis, and compartment syndrome.6

The main effects of the Bothrops venon are related with coagulation disorders, hemorrhage and local tissue damage. Most of bothropic venoms are composed by metalloproteases, which are responsible for pro- and anti- coagulant disorders and hemorrhage; Serine proteases, which affect different factors involved in the coagulation cascade; Phospholipases A2, which have myotoxic, and neurotoxic effects, generate edema, platelet aggregation disturbance, and tissue damage, among others effects; L-amino acid oxidases, that induce the release of H2O2, with cytotoxic effects, as well as induction of hemorrhage and apoptosis, and inhibition of platelet aggregation; and C-type lectins, which disrupts blood homeostasis by inducing/ inhibiting platelet aggregation or activating/consuming coagulation factors.7 Bothrops present an ontogenetic shift in its venom composition. The venom of adult specimens shows predominantly proteolytic activity and local tissue damage, whereas the venom of juveniles causes mainly hemorrhagic disorders.4,6 Although in the case presented in this study, we did not recover the snake responsible for the accident, the great hemorrhagic manifestations make us believe that the accident was caused by a young snake. Although ophidic accidents have a certain frequency worldwide, the most common is the presence of a single snakebite mark, with two being very uncommon and several being extremely rare, drawing our attention to this case and serving as a predictor of severity. In addition, the hemorrhagic manifestations of this case have important differential diagnoses often seen in emergency departments, such as intracranial hemorrhage secondary to ruptured aneurysms, and hemothorax from chest trauma.

Conclusion

This case provides imaging findings including intraparenchymal hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, hemothorax, and signs of soft tissue edema at the site of the snakebite, all at once. Therefore, it is essential for the emergency physician to be aware of imaging features of the hemorrhagic manifestations of ophidic accidents, to take the correct therapeutic approach, such as neuroprotective measures.