Introduction

Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (RLH), also referred as pseudolymphoma or nodular lymphoid hyperplasia is characterized by a localized non-neoplastic proliferation of lymphoid tissue at extranodal sites.1,2,3 Being most commonly described on the skin, orbit, thyroid, lung and gastrointestinal mucosa-lined structures such as the intestine or the stomach, its occurrence in the liver is exceedingly rare, with less than 100 cases ever described in the literature, most of the times misdiagnosed as an hepatic malignant lesion, namely hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), but also cholangiocarcinoma (CC) and metastatic lesions (e.g. neuroendocrine tumors), thus making the diagnosis of liver RLH very challenging without needle biopsy or surgical resection.2,3,4

Clinical Case

A 49 year-old asymptomatic female with a clinical background relevant for sustained viral response for hepatitis C (HCV), who in 2020 underwent a left hepatectomy following the detection of a suspicious hepatic nodule 3 years earlier.

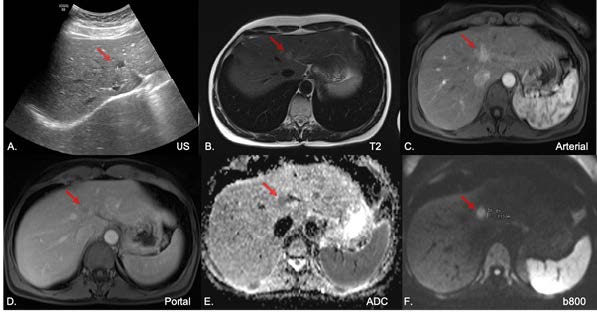

In September 2017, a routine abdominal ultrasound examination identified a “de novo” hypoechoic solitary liver nodule in segment IVa with 11 mm axial maximum diameter (Figure 1). Subsequent CT (February 2018) confirmed the presence of a focal lesion with a slight arterial enhancement and non-peripheral washout on portal/delayed phases within an hepatic background considered normal on both imaging modalities. Four months later, further investigation was conducted by MRI with an extracellular contrast (Figure 1), revealing diameter stability of the small lesion, with low and moderate signal intensity on T1W Fat Saturated and T2W respectively, marked diffusion restriction and wash-in/wash-out suspicious for malignancy, especially HCC. On both CT and MRI there was no evidence of abdominopelvic extra- hepatic neoplasm.

In keeping with the radiologist’s suspicion of malignancy, an ultrasound guided biopsy was conducted revealing a slight parenchymal fibrosis and lymphocytic infiltrates interpreted in the context of a prior HCV infection, with absence of worrisome atypical features.

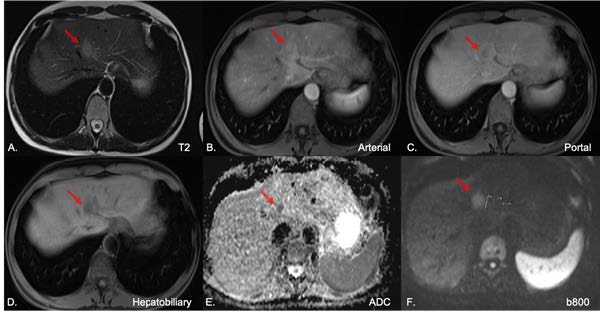

Upon multidisciplinary discussion, lesion imaging follow- up was put forward. In spite of lesion stability for 1,5 years and absence of cirrhosis, given the history of HCV infection and worrisome imaging characteristics, a second percutaneous biopsy was attempted in November 2019 revealing an indeterminate lymphocytic T infiltrate. (Figure 3). On June 2020 a MRI with a hepatocyte- selective agent (gadobenate dimeglumine, MultiHance®) was relevant for nodular growth (20 mm vs 11 mm), with moderate arterial enhancement and central wash- out on portal/delayed phases, and hypointensity on the hepatobiliary phase (Figure 2). Due to interval growth and concerning imaging features, surgical resection of the left hepatic lobe was decided; specimen pathological examination was consistent with RLH.

During this period of time (2017-2020) laboratory tests were unremarkable, including liver function tests and tumor markers (alpha fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 19.9). Fibroscan® measurements were within normal range (3-4 kPa).

No recurrence of the liver nodule was detected at the 3 month imaging follow-up.

Figure 1: Ultrasound (A) documen- ting an hypoechoic liver nodule in segment IVa, represented at MRI by a moderate T2 signal intensity nodule (B) with dynamic wash-in/wash-out (C,D) and diffusion restriction (E, F).

Figure 2: Contrast enhanced MRI with hepatobiliary agent (2020) documenting persistence of the focal hepatic lesion with moderate T2 hyperintensity (A), dynamic wash-in/ wash-out (B,C), hypointensity at the hepatobiliary phase (D), diffusion restriction (E,F) and apparent inter- val growth (F).

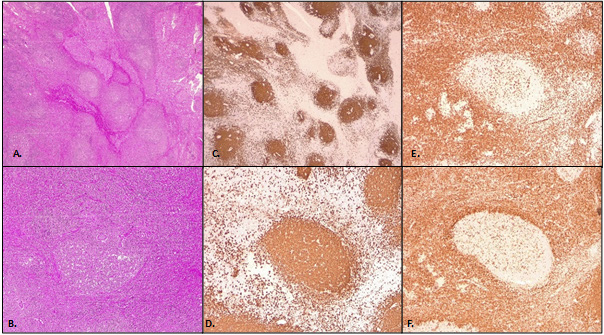

Figure 3: Reactive lymphoid follicles in a hematoxylin and eosin staining with 40x (A) and 100x magnification (B); Lymphoid follicles are composed of B-cells, highlighted by CD20 staining with 40x (C) and 100x magnification (D); Interfolli- cular areas composed of T-cells, highlighted by CD3 staining with 100x magnification (E); Absence of BCL2 staining is characteristic of non-neoplastic germinal centers, with 100x magnification (F).

Discussion

Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia was first reported in 1981 by Snover D et al.5 RLH is a benign lesion with no malignant potential, characterized by a marked proliferation of polyclonal lymphocytes organized into follicles with an active germinal center, frequently described in the skin, lung, orbit, intestine and thyroid, but an uncommon finding in the liver.1,3The precise etiology and pathogenesis is unknown, but it is speculated by some authors to represent a reactive immunological response to a chronic inflammatory liver process.3

In a recent literature review, Kanno H et al.3 (2020) found only 76 cases of hepatic RLH reported in the medical literature since 1981. Of these, most occurred in asymptomatic females (93.4%) with an average age of 56.7 years old and with liver (35.5 %), autoimmune (17.1 %) or malignant diseases (27.6%). Most of the times RLH presented as a solitary lesions (84.7%) with less than 20 mm in the greater diameter (81.3%) and located in the right hepatic lobe (62.9%). Because most lesions were misdiagnosed as malignant, surgical resection was performed in a majority of cases (82.9%).3

The diagnosis of RLH of the liver is made problematic by the nonspecific imaging features and significant overlap with liver malignancy, exhibiting various patterns of dynamic enhancement, but mostly with wash-in/ wash-out and occasionally perinodular enhancement or pseudocapsule. Thus, it is extremely difficult to differentiate hepatic RLH from malignant tumors such as HCC and hypervascular metastatic tumors based on imaging findings alone.1,2,3,4On MRI, RLH usually exhibits a homogeneous low signal intensity (SI) on T1W and moderate on T2W.3,4In the largest RLH series published to date (n=20), Zhou Y et al concluded that a homogeneous nodule with less than <2 cm, hypervascular with lower SI than that of portal vein on arterial phase and lower ADC value than the spleen is a common MRI presentation of hepatic RLH, with most lesions exhibiting a wash-in/wash-out pattern of enhacement (12/20).6

In our particular case, contrast-enhanced MRI showed a non-cirrhotic liver with an isolated hypervascular lesion with wash-out. This lesion showed lack of uptake on hepatobiliary phase, which is seen in HCC and hepatic adenoma, but argues against focal nodular hyperplasia. In spite of the normal liver morphology, hepatocellular carcinoma was an important differential diagnosis to be considered not only because of the dynamic features but also ancillary features such as moderate T2W hyperintensity, hepatobiliary phase hypointensity, restricted diffusion and late growth. On the other hand, one must consider that there is a considerable reduction in the risk of HCC in HCV- infected patients cured with direct acting antiviral agents, and that dynamic wash-in/wash-out features have only high specificity for HCC in a cirrhotic liver.7,8,9Additionally, sustained unremarkable levels of alpha fetoprotein and 2 negative biopsies also argue against HCC in this particular patient. The possibility of a neuroendocrine lesion was considered unlikely due to absent abdominopelvic primary tumor and inconsistency with the biopsy histology. In accordance to the second biopsy result, a lymphocytic process was considered, although its nature was unknown (reactive vs primary MALT lymphoma). Typically, liver lymphoma nodules are hypointense on dynamic assessment, albeit reports of hypervascular lesions with wash-out can be found in the literature.10,11Mostly due to uncertainty of the diagnosis but also because of the imaging characteristics and apparent growth, surgical treatment was undertaken.

Histologically, RLH consist of prominent hyperplastic lymphoid follicles, lymphocytes, and other inflammatory cells. An accurate diagnosis of pseudolymphoma relies mostly on the immunohistochemical analysis.2,11Usually, immunohistochemical staining shows positivity for CD3, CD4, CD8 (T cell markers) in the interfollicular areas and CD20 and CD79a (B cell markers) in the follicles. In the germinal centers the B-cells are positive for CD10 and BCL6 and negative for BCL2, thus indicating the RLH’s reactive and nonneoplastic nature.2,11In accordance with these findings, in our case the immunohistochemical stain (Figure 3) showed that the follicles were composed of CD20 (+), Bcl-2 (-) B cells, and the interfollicular area was composed of CD3 (+) small T cells.

RLH of the liver is considered a benign lesion with no reports of malignant transformation to the best of our knowledge, and volumetric regression has been observed in conservative treated RLH diagnosed by needle biopsy.1,4,8

Conclusion

Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of liver is an extremely rare disease with similar radiological features to hepatocellular carcinoma. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis of small hepatic tumors in which biopsy fails to demonstrate malignant cells, particularly when a single incidental hypervascular lesion is found in a non-cirrhotic liver in an asymptomatic female patient with systemic autoimmune or liver disease.

![Variabilidade Sazonal da Captação de [18F]FDG em Gordura Castanha na mesma Doente](/img/pt/next.gif)