Background

The peroneus brevis (PB) and the peroneus longus (PL) tendons are the primary lateral ankle stabilizers and can show several associated anatomical variants. Some variants predispose to peroneal injury and, thus, must be recognized. Peroneal lesions are often overlooked when patients present with lateral ankle complaints.1,2It is essential to recognize them, to prevent further ankle dysfunction3 and to allow a safe return to physical activity.4

This article intends to review and illustrate the normal anatomy of the peroneal tendons, as well as its anatomical variations. We also describe the imaging features of common and uncommon disorders that can affect the peroneal tendons.

Anatomy of the peroneal tendon complex

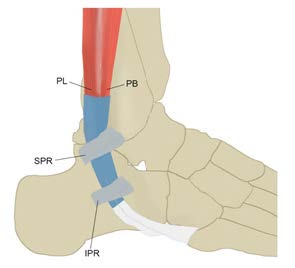

The peroneal tendon complex is in the lateral compartment of the leg and foot and includes the PB and PL muscles and tendons, the common peroneal tendon sheath, and the superior and inferior peroneal retinaculum (Fig. 1).5,6

The PB muscle originates from the distal two-thirds of the lateral fibula and the adjoining intermuscular septa and its tendon inserts on the lateral tubercle of the base of the fifth metatarsal. The PL muscle arises from the lateral condyle of the tibia, the head and proximal two-thirds of the lateral fibula, the intermuscular septa, and the adjacent fascia; its tendon courses medially, crossing the calcaneocuboid joint and coursing along the sulcus at the inferolateral aspect of the cuboid bone in the cuboid canal, and inserts on the plantar lateral surface of the medial cuneiform and the plantar lateral surface of the base of the first metatarsal.5,6The peroneal muscles are innervated by the superficial peroneal nerve and supplied by the peroneal artery.5,7Their primary role is eversion of the foot and plantar flexion and they have a secondary function as an essential stabilizer of the lateral aspect of the ankle joint.6

At the ankle joint, the PB and PL tendons are situated in the retromalleolar groove, where the PB tendon is anteromedial to the PL tendon, and share a common synovial sheath (Fig. 1). The common synovial sheath splits at the level of the peroneal tubercle into two separate sheaths enclosing their respective tendons deep to the inferior peroneal retinaculum, with the PB tendon coursing superiorly to the PL tendon.

The peroneal retinacula are fibrous bands that stabilize the PB and PL tendons as these tendons cross the lateral aspect of the ankle (Fig. 1). The SPR is a short band that extends from the posterior ridge of the lateral malleolus, running posteriorly and inferiorly to the lateral surface of the calcaneus. The inferior peroneal retinaculum (IPR) extends from the posterior lateral rim of the sinus tarsi in continuation with the inferior extensor retinaculum to the lateral aspect of the calcaneus below and onto the retrotrochlear eminence. Some of its fibers fuse with the periosteum on the peroneal tubercle of the calcaneus, creating a septum between the PB tendon superiorly and the PL tendon inferiorly.5,7

Figure 1: Illustration of the peroneal tendon complex. The PL (peroneus longus) and PB (peroneus brevis) tendons run posteriorly to the lateral malleolus. The PB tendon inserts on the base of the fifth metatarsal, whereas the PL tendon runs medially to insert on the medial cuneiform and base of the first metatarsal. The peroneal tendons are stabilized by the SPR (superior peroneal retinaculum) and IPR (inferior peroneal retinaculum).

MR imaging technique

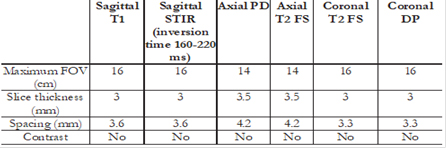

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has a crucial role in the evaluation of the peroneal tendons. In our institution, MRI is performed in 1.5-T or 3-T systems, with the patient in the supine position and with the foot in 20º plantar flexion. A brief description of our protocol is listed in table 1. Imaging is performed in the axial, coronal, and sagittal planes. The morphology and relative position of the peroneal tendons are best characterized in the axial plane. The axial plane is also the best plane to assess the morphology of the SPR. The coronal and sagittal planes are helpful as a complement. Contrast is used if infection is suspected or to distinguish a solid from a cystic ankle mass.

Peroneal tendon pathology

Anatomical variants

Several ankle anatomical variants can be seen in asymptomatic subjects. Some predispose to peroneal pathology by causing overcrowding of the peroneal groove and, therefore, must be documented.8

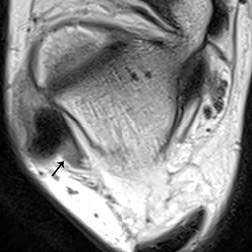

Low-lying peroneus brevis muscle belly

Low-lying PB muscle belly is a common anatomical variant, present in up to 33% of the population. Since it causes retinaculum laxity, it is a potential cause of peroneal injuries, such as PB tears and intrasheath peroneal subluxation.9 The muscle belly of the PB frequently extends below the peroneal groove in asymptomatic patients;10 therefore, a low lying muscle belly (Fig. 2) must be considered only if it extends more than 15 mm below the fibular tip.8

Peroneus quartus muscle

The peroneus quartus muscle is an accessory muscle that originates in the lower leg and inserts in the lateral hindfoot.10 It is present in 5.2%11 to 21.7% of the population.12

The peroneus quartus arises at the level of the distal fibula, in most cases from the PB muscle belly.12 Its insertion is highly variable but is commonly on the retrotrochlear eminence of the calcaneus.13 Other described insertions include the base of the fifth metatarsal, the inferior extensor retinaculum, and the cuboid bone.11

The presence of peroneus quartus is mostly asymptomatic, but it is a potential cause of groove overcrowding.10

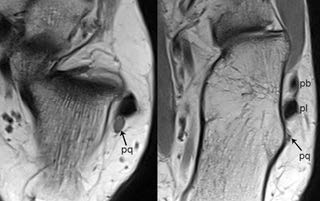

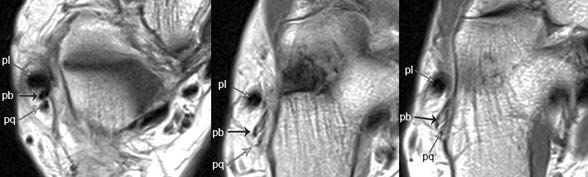

On imaging, the peroneus quartus is seen as a muscle belly or tendon running posteromedially to the peroneus brevis (Fig. 3), separated from the remaining peroneal tendons by fat.14

Variants of the insertion of the PB tendon

Some reports have described anatomical variability in the distal insertion of the PB tendon.15 These variants include insertion on the peroneal tubercle,16 on the lateral wall of the calcaneus distally to peroneal tubercle,17 and the retrotrochlear eminence (Fig. 4). These variants must be recognized to avoid a misdiagnosis of a distal PB tendon tear.

Hypertrophic peroneal tubercle

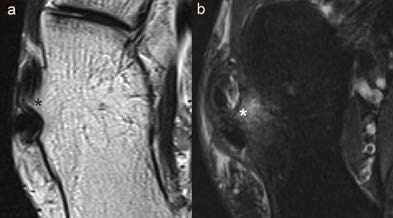

The peroneal tubercle is a bony protuberance that can be seen along the lateral calcaneus in some patients.14 In a study of 65 asymptomatic volunteers, a peroneal tubercle was found in 55% of the ankles.8

It is located inferiorly to the lateral malleolus18 and divides the peroneal tendons distally to the fibula’s tip. It is considered enlarged when it measures more than 5mm.6,8,15This abnormality can be congenital or acquired20 and is found in 20% of the population. It is essential to recognize it because it predisposes to tenosynovitis and longitudinal peroneal tendon tears,21,22particularly of the PL tendon.23 On MRI, concomitant bone marrow edema can be present (Fig. 5) due to tendon attrition or secondary to hypervascularization of the underlying tendinous sheath.19,24

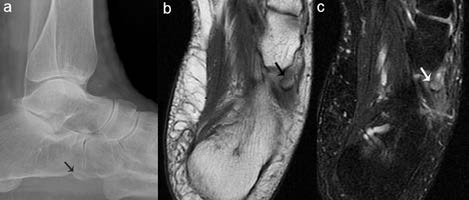

Os peroneum

The os peroneum is a sesamoid bone localized in the PL tendon, at the level of the calcaneocuboid joint.25,26Its ossified form can be seen in 2 to 26 % of the population.27 In 30% of the cases, the os peroneum can be multipartite or bipartite.28 In most patients, it is asymptomatic, but impingement can occur in some patients, mainly if it is hypertrophic or due to overuse.29

Figure 4: Variant of the PB tendon insertion (retrotrochlear eminence). Axial MR PD-WI show an abnormally positioned PB tendon (pb-black arrow), located posteriorly to the PL tendon (pl) and with a variant insertion on the retrotrochlear eminence. Furthermore, a peroneus quartus (pq) muscle is also seen, posteriorly to the PB tendon.

Figure 5: Hypertrophic peroneal tubercle. Axial MR T2-WI (a) and T2-WI with fat saturation (b) show a prominent peroneal tubercle (*), separating the PB tendon (anteriorly) from the PL tendon (posteriorly). There is underlying bone marrow edema.

When present, the os peroneum is depicted as a structure with bone marrow signal within the PL tendon. Caution is required in order not to misdiagnose it as a PL tear at first glance.10

The painful os peroneum syndrome (POPS) was initially described by Sobel et al.30 and is caused by several disorders related to this ossicle. These include fractures of the os peroneum, diastasis of a multipartite ossicle; tear of the PL tendon proximal or at the level of an os peroneum; and PL or os peroneum entrapment caused by an enlarged peroneal tubercle. These conditions clinically present as lateral pain over the os peroneum or the cuboid bone.

MR is the gold standard in the diagnosis of POPS. It can show bone marrow edema at the os peroneum (Fig. 6) or at the level of the cuboid bone, in association with edema of the surrounding soft tissues, seen as high signal intensity on fluid-sensitive sequences.29

Figure 6: Os peroneum. Lateral ankle x-ray (a) and axial MR PD-WI (b) and T2-WI with fat saturation (c) show an os peroneum (arrows) at the level of the calcaneocuboid joint, with associated bone marrow edema (seen on c).

Conservative management is the initial treatment for most conditions causing POPS. When it fails, patients must undergo surgery which, in most cases, includes excision of the os peroneum and repair/tenodesis to correct the resulting gap.31

Intrinsic tendon pathology

Tendinosis/tendinopathy

Most peroneal tendinosis/tendinopathy cases are due to chronic overuse, but they can also occur in the setting of acute traumatic injuries. Conditions that cause peroneal groove overcrowding, such as peroneal tubercle hypertrophy and peroneus quartus muscle, increase the risk of peroneal tendinosis.4,32Chronic ankle instability with repetitive inversion is also a risk factor for peroneal tendinopathy. Due to its position in the retromalleolar groove, the PB tendon has a higher risk of developing tendinopathy than the PL tendon.4 A pes cavus deformity also increases the stress over the peroneal tendons,33 but it is typically associated with PL tendinosis.

Patients present with pain and edema along the peroneal tendons. In PB tendinosis, pain is typically described at the level of the fibular tip whereas if the PL is involved, soreness is referred usually bellow the retromalleolar groove. These symptoms can be caused by provocative tests such as attempts of dorsiflexion and eversion of the foot.34

On imaging, the affected tendon appears enlarged and heterogeneous (Fig. 7). Concomitant tenosynovitis or ligament damage may also be present.35

Treatment of peroneal tendinosis/tendinopathy relies initially on conservative measures, such as anti-inflammatory therapy associated with rest. If there is associated ankle instability, physical therapy must be initiated to strengthen the muscles and improve articular range of motion.36 In cases of hindfoot malalignment, the initial treatment includes the use of corrective orthotic. If the symptoms persist despite it, surgery may be required.37

Tears

Some systemic conditions increase the risk of peroneal tendon tears, such as diabetes mellitus, collagen vascular diseases, and steroid intake.38

Similarly to tendinosis, tears of the PB are more common than those of the PL tendon because the first gets entrapped between the retromalleolar sulcus and the PL tendon.13 Although PB tendon tears can be acute, most of them are chronic.39 Acute peroneal tears are more common in young athletes,40 in the setting of severe inversional lateral sprains or fractures.2,34

Degenerative tears can be caused by repetitive subluxation, either due to retinaculum damage or secondary to conditions that cause groove overcrowding.2,41These include several anatomical variants such as a convex or flat fibular groove, a low-lying PB muscle belly, and the presence of a posterolateral fibular spur.1 Thus, PB tendon tears are most common at the level of the retromalleolar groove.42

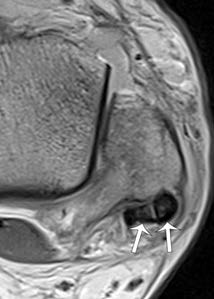

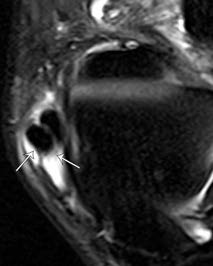

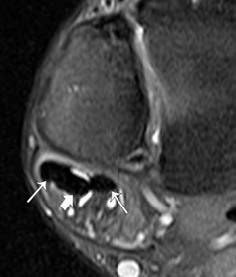

Isolated tears of the PL tendon are uncommon34 and mostly degenerative. Those tears occur typically in the presence of an os peroneum,2,41distally or at the level of the ossicle in the cuboid groove.41 The presence of a cavus foot deformity also increases the risk of a PL tear.43 Peroneal tendon tears are often overlooked and sometimes misdiagnosed as sprains since they present with vague symptoms, such as ankle edema and retrofibular pain.35,44,42On MRI, the torn peroneus brevis tendon typically appears with a C-shape on the axial plane, partially encasing the PL tendon at the malleolus.35,40Other findings that suggest peroneal tears are tendon splitting into two hemitendons (Fig. 8), tendon discontinuity (Fig. 9), or an abrupt modification of the tendon caliber.35

Lamn et al.45 reported that MRI has a sensitivity and a specificity of 83% and 75%, respectively, in the detection of PB tears, confirmed by surgery. Thus, it is essential to always correlate MRI results with adequate physical examination.35,46Peroneal tendons are particularly susceptible to magic angle artifacts, especially in the inframalleolar region, in sequences with a short echo time. This can mimic a tendon tear in MRI and be the cause of a high number of false positives.10,40,47

The management of peroneal tendon tears relies on conservative treatment, encompassing rest and activity modification. If conservative treatment fails or if the patient is an athlete, surgical treatment is indicated,1,34,39involving tendon debridement, tubularization, tenodesis, or autograft.21 Retinaculum repair and correction of underlying anatomical abnormalities or fractures may also be required.4

Figure 8: Longitudinal split PB tendon tear. Axial MR T2-WI with fat saturation shows a longitudinal split of the PB into two hemitendons (thin arrows), that encircle the PL tendon (thick arrow).

Intratendinous ganglion cysts

Ganglion cysts are benign cystic lesions that appear in the connective tissue of tendon sheaths, bone, and muscles. Although rare, intratendinous ganglion cysts can also occur.48 Intratendinous ganglion cysts are believed to be secondary to degeneration and are more commonly seen in the wrist than in the ankle.49

On the ankle, ganglionic cysts can present as a lump or cause neurological symptoms if the peroneal nerve is compressed.50

On MRI, intratendinous ganglion cysts present as a well-defined cystic lesion within a tendon, with high signal intensity on T2-WI (Fig. 10) and peripheral rim enhancement.48 MRI can help to define the extension and aid in surgical planning.51

The treatment of ganglionic cysts usually relies on surgical resection.52

Tendon sheath pathology

Tenosynovitis

Peroneal tenosynovitis may be caused by infection, systemic arthropathies such as rheumatoid arthritis and by repetitive tendon stress.53,32It presents typically as pain and tenderness along the peroneal tendon territory.34 Tenosynovitis is most commonly seen in the common peroneal tendon sheath but can also be seen in each sheath individually. In cases of POPS, the PL tendon sheath is typically affected without the involvement of the PB tendon.54

On imaging, tenosynovitis is depicted as fluid within the tendon sheath (Fig. 11). However, a small amount of fluid may be expected at the common peroneal tendon sheath in normal tendons.10,46A calcaneofibular ligament injury may also lead to the presence of fluid in the peroneal tendon sheath, so the integrity of this ligament must be carefully assessed.55

Conservative treatment of tenosynovitis is usually effective and includes immobilization in association with ice and anti- inflammatory drugs. Surgery is indicated if conservative treatment fails.43

Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVS)

PVS is characterized by an abnormal proliferation of the synovial villi, affecting synovium, tendon synovial sheaths, and bursae. Its etiology is unknown, and it can be classified in two forms: focal and diffuse.56,57,58The focal process that affects tendons is also termed tenosynovial giant cell tumor.59 It is more common around the knee,58 whereas PVS of the foot and ankle corresponds to less than 10% of the cases.60

The diagnosis of PVS of the ankle is often delayed since symptoms are nonspecific.58 It presents typically as a painful mass, and joint edema may also be present.61

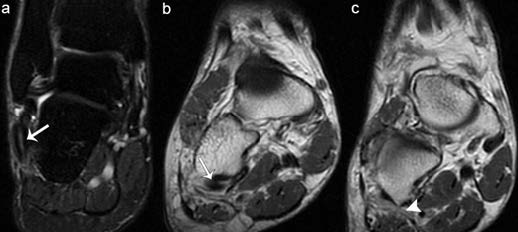

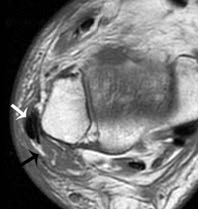

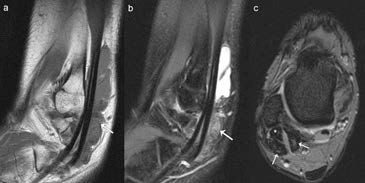

MRI is the gold standard in the diagnosis of PVS.56 On T1- WI, the thickened synovium has low to intermediate signal intensity and low signal intensity on T2-WI. The typical feature is the presence of blooming artifact on gradient echo sequences (Fig. 12) due to hemosiderin deposition. Occasionally fibrous septa, hypointense on both T1 and T2-WI may be seen.51,56,61

The treatment of ankle PVS may be challenging, and it is associated with a high recurrence rate.57,58In some cases, surgery associated with radiotherapy is required.60

Figure 12: Pigmented villonodular synovitis of the peroneal tendons. Sagittal MR T1-WI (a) and T2-WI with fat saturation (b) show frond- like thickened synovium with low signal intensity (arrows). There is also fluid within the peroneal tendon sheath (c). Axial MR GRE (gradient recalled echo) T2*-WI (c) shows significant blooming artefact (arrows) surrounding the peroneal tendons (*).

Retinaculum pathology and instability

Subluxation and dislocation

Peroneal dislocation and recurrent subluxation are mainly consequences of either injury or increased laxity of the SPR.4,55,62,63Other risk factors for peroneal subluxation are a convex retromalleolar groove and calcaneus varus.13 Peroneal dislocation can be acute or chronic. The injury mechanism typically described in acute dislocations is dorsiflexion and ankle inversion, with a sudden contraction of the peroneals.4,13It is more common in athletes who practice sports associated with “cutting” movements, such as ski, soccer, and football.3,34Acute subluxation can mimic an ankle sprain at presentation in these cases,34,62,64with pain and ecchymosis.

Chronic dislocation is associated with recurrent inversion sprains and instability. Patients with a chronic subluxation may describe a “snapping” sensation that can be reproduced with provocative maneuvers.34

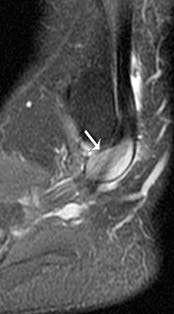

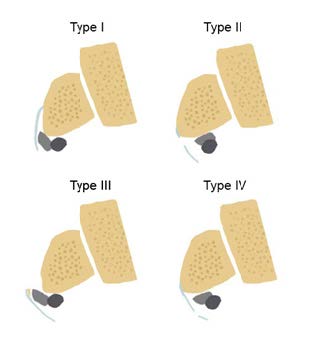

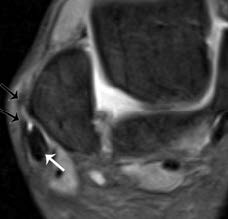

The relationship of the peroneal tendons with the retromalleolar groove and the integrity of the SPR are best depicted on axial MR images.55 The Oden modification of the Eckert classification divides SPR injuries into four grades (Fig. 13). Type I lesions are the most common and consist of stripping off of the periosteal attachment of the SPR at the peroneal groove, creating a pouch where the peroneal tendons can dislocate into (Fig. 14). In type II lesions, there is a tear of the SPR at its attachment in the fibula (Fig. 15). Type III lesions are characterized by an avulsion fracture of the distal fibula where the SPR attaches to the lateral malleolus. This is the second most common type of SPR injury. Finally, in type IV lesions, there is a tear of the posterior attachment of the SPR.65

Figure 13: Illustration of the Oden modification of the Eckert classification of SPR injuries. Type I - stripping off the attachment of the SPR at the fibular groove, forming a pouch where the peroneal tendons can dislocate into. Type II - tear of the SPR at its attachment in the fibula. Type III - avulsion fracture of the distal fibula, where the SPR inserts. Type IV - tear of the posterior attachment of the SPR.

Conservative treatment must be considered after acute dislocation in non-athletes, consisting of reduction followed by immobilization. However, surgical repair is required in athletes,21 when conservative treatment fails in non- athletic patients and in most cases of chronic instability.64 Surgery involves SPR repair and correction of anatomical predisposing conditions, for example, deepening of a shallow fibular groove.62

Figure 14: Type I SPR injury. Axial MR T2-WI with fat saturation shows stripping of the SPR (black arrow), at its insertion in the fibula, resulting in subluxation of the peroneal tendons (white arrow). There is also tibiotarsal joint effusion and diffuse edema of the soft tissues.

Intrasheath subluxation of the peroneals

In this condition, there is subluxation of one peroneal tendon over the other, under an intact SPR. Raikin described two types of lesions.66 In type A, the peroneal tendons switch their relative positions and remain contained by a normal retinaculum. In type B lesions, subluxation of the PL tendon occurs through a longitudinal split within the PB tendon.67 The SPR is also intact in this form.66

Dynamic ultrasound of the ankle is the best imaging method to assess patients with suspected intrasheath subluxation since MRI studies may be normal.5

Conclusion

Peroneal tendons can show complex anatomical variants that can lead to tendon stress or, in other cases, be misdiagnosed as tendon tears. Furthermore, peroneal tendons can be affected by a spectrum of tendinopathies in athletes and non-athletic patients that can be disabling. MRI is an essential tool in evaluating the peroneal tendon complex by identifying its anatomical variations and injuries.