Introduction

Although highly vascularised and with a significant incidence of benign and malignant diseases that further increase its vascularisation, spontaneous thyroid bleeding is rare, and most cases are mild.1,2,3However, the risk of bleeding due to goitre or nodular disease-induced abnormal vascularity, triggered by the use of anticoagulants, can cause massive haemorrhage and sudden unexpected airway compromise.1,2,4

We describe a case of spontaneous bleeding of a thyroid nodule, with capsular disruption and extension of the haematoma to the deep cervical planes, in a chronic anticoagulated patient.

Case Presentation

A 75-year-old woman presented to the emergency department complaining of a painful mass on the left side of the neck that developed overnight, along with dysphagia. There was no history of trauma, fever, cough, recent medical procedures or previous thyroid disease.

She had a known background of hypertension, polycythaemia vera and atrial fibrillation and was medicated with hydroxyurea, lercanidipine, amiodarone, clopidogrel, olmesartan and tinzaparin sodium, a low molecular weight heparin.

The patient was afebrile, eupnoeic at rest, without stridor. Neck examination revealed a hard lesion confined to the left side of the neck with approximately 10 cm, painful on palpation, adherent to surrounding tissues, non-pulsatile, without associated palpable adenopathies in the cervical chains. Preliminary laryngoscopy was otherwise normal, except for paralysis of the left vocal cord.

Laboratory workup showed a slightly low haemoglobin level of 11.1g/dL [normal range = 12.1 to 15.1 g/dL], platelet count of 522x10^9 [normal range = 150-450 x 10^9], normal prothrombin time of 12.9s, elevated activated partial thromboplastin time of 58.1 s [normal range = 25.1-36.5s] and elevated fT4 of 1.54 g/dL [normal range = 0.54-1.24 g/dL] with normal thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level.

Ultrasound study of the neck (Fig. 1) showed a left lobe thyroid nodule measuring approximately 85x60x55mm, with mixed cystic and solid content, with central inhomogeneous fluid and fluid-fluid level, causing trachea deviation, suggestive of a haemorrhagic thyroid nodule.

Figure 1: Cervical ultrasound (A-C) demonstrates a thyroid nodule with mixed cystic and solid content, central inhomogeneous fluid, fluid- fluid level and trachea (T) deviation.

To establish the extension of the process, a neck Computed Tomography (CT) was obtained (Fig. 2), without contrast administration because of significant renal impairment, confirming a large thyroid nodule in the left lobe, with areas of recent haemorrhage depicted by intra-nodular hyper-attenuating portions and fluid-fluid levels, with apparent posterosuperior disruption of the capsule and extension of the process to the hypopharynx with mass effect, causing obliteration of the pyriform sinus and deviation of the trachea. There was extensive oedema in the left parapharyngeal space, carotid space and crossing the midline through the retropharyngeal/danger spaces.

Figure 2: Non-contrast-enhanced soft-tissue window neck CT scan, with multiplanar reformats on the axial (A,C) and coronal (B) planes. A and B show a large thyroid nodule in the left lobe with intra-nodular hyper-attenuating portions and a fluid-fluid level, with apparent disruption of the capsule posteriorly (arrow), and significant tracheal deviation. The axial plane of the hypopharynx (C) shows the extension of the bleeding outside the thyroid, with obliteration of the pyriform sinus and the left parapharyngeal, carotid and retropharyngeal/ danger spaces.

Indirect laryngoscopy was repeated and revealed a submucosal left hypopharynx haematoma with obliteration of the pyriform sinus and permeable glottis.

Based on the clinical and radiological findings, spontaneous thyroid nodule bleeding was diagnosed with capsular disruption and hypopharynx haematoma.

Anticoagulation was promptly reversed. The patient developed respiratory distress, therefore, after securing the airway, she underwent urgent hemithyroidectomy.

The surgical exploration described a left lobe thyroid nodule with extensive haemorrhage and capsular rupture on its superior part, with an extension of the haematoma to the pharynx/hypopharynx and laterosuperior cervical planes, with significant tracheal deviation.

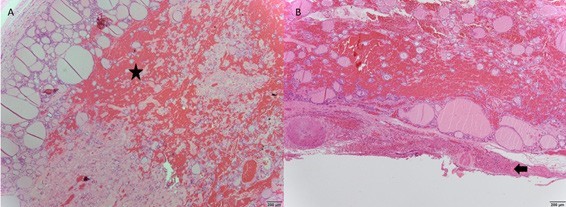

The study of the surgical specimen (Fig. 3) confirmed the existence of a dominant hyperplastic nodule in the left lobe, with extensive central haemorrhage and pseudocapsule rupture. The bleeding extended to the adjacent soft tissues. There were no neoplastic cells.

The patient clinically improved and was discharged five days after surgery.

Discussion

Although the thyroid is a very vascularized organ, spontaneous haemorrhage, not related to previous trauma or interventional procedures, is not frequent and usually confined to the gland. There are not many cases described in the literature.

Pre-existing thyroid conditions such as solitary or multiple benign or malignant nodules, cystic nodules and colloid goitre are risk factors increasing the vascularity of the gland and vulnerability for bleeding.1,2,3,4

The origin of the haemorrhage is mainly venous, and the possible mechanisms may be related to abnormal thyroid vascular anatomy with venous fragility and the creation of arteriovenous shunting inside the nodules, conditioning intra-nodular haemorrhage. Factors favouring an increase in venous pressure, such as Valsalva, coughing or exercise, may raise the probability of spontaneous bleeding.2,4,5,6Moreover, patients on anticoagulation therapy have more risk of haemorrhage, although no cases of thyroid haemorrhage were revealed in the trials across all anticoagulants, maybe because this complication is not captured in many of these trials.1,2

In mild cases, patients with acute thyroid bleeding present sudden neck bulging with local discomfort or pain and frequent dysphagia. In severe cases, it can result in a large expanding haematoma with capsule rupture, with haemorrhage extending to cervical planes, resulting in sudden compression of the trachea, causing dyspnoea and stridor, and leading to possible upper airway obstruction.1,2,4,5Furthermore, thyroid bleeding can cause a sudden release of preformed thyroid hormones and acute hyperthyroidism, which is usually self-limiting, needing no treatment.1 It is essential to consider other possible and rare causes of spontaneous cervical haemorrhage, such as lesions of the upper and lower thyroid arteries and lesions of the parathyroid glands.7

Laboratory blood tests for coagulation and hormonal status should be obtained. Ultrasound evaluation is essential for proper diagnosis and may be helpful in distinction from other acute neck conditions. Nevertheless, in more severe cases, when there is massive bleeding with clinical signs of airway or hemodynamic compromise, patients should be evaluated by CT scan, preferably with contrast administration.4

As a therapeutic approach, securing the airway with endotracheal intubation is the most critical action before any diagnostic and treatment procedures, and, if possible, anticoagulation should be reversed immediately.2 Conservative treatment is the preferred choice for most patients, but early surgical decompression should be considered whenever tracheal compression is a concern or when bleeding is not controlled.1,5Patients managed conservatively should be referred for ambulatory endocrinology follow-up, namely because bleeding could arise as the first sign of malignant thyroid disease.4

Conclusion

It is essential to remember that thyroid haemorrhage can have life-threatening presentations, severe enough to require emergency surgery. Knowing the typical clinical signs and symptoms is mandatory in order to have a good and fast approach. Imaging features of thyroid bleeding can ensure the proper diagnosis and lead to adequate and prompt treatment. Therefore, the collaboration between emergency department physicians, otorhinolaryngologists, radiologists and general surgeons is needed for a satisfactory outcome in these cases.