Case Presentation

A 74-year-old woman with a previous history (9 yrs. prior) of stage III multiple myeloma presented to the emergency department with complaints of abdominal discomfort and painless jaundice. On admission, her lab work showed elevation of alanine transaminase 206 IU/L, aspartate aminotransferase 194 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 425 IU/L, gamma-glutamyl transferase 1038 IU/L, total bilirubin 10 mg/dL, and direct bilirubin 7.8 mg/dL, with normal lipase, amylase, and white blood cell count. Physical exam revealed diffuse jaundice; however, abdominal palpation did not reveal any focal findings.

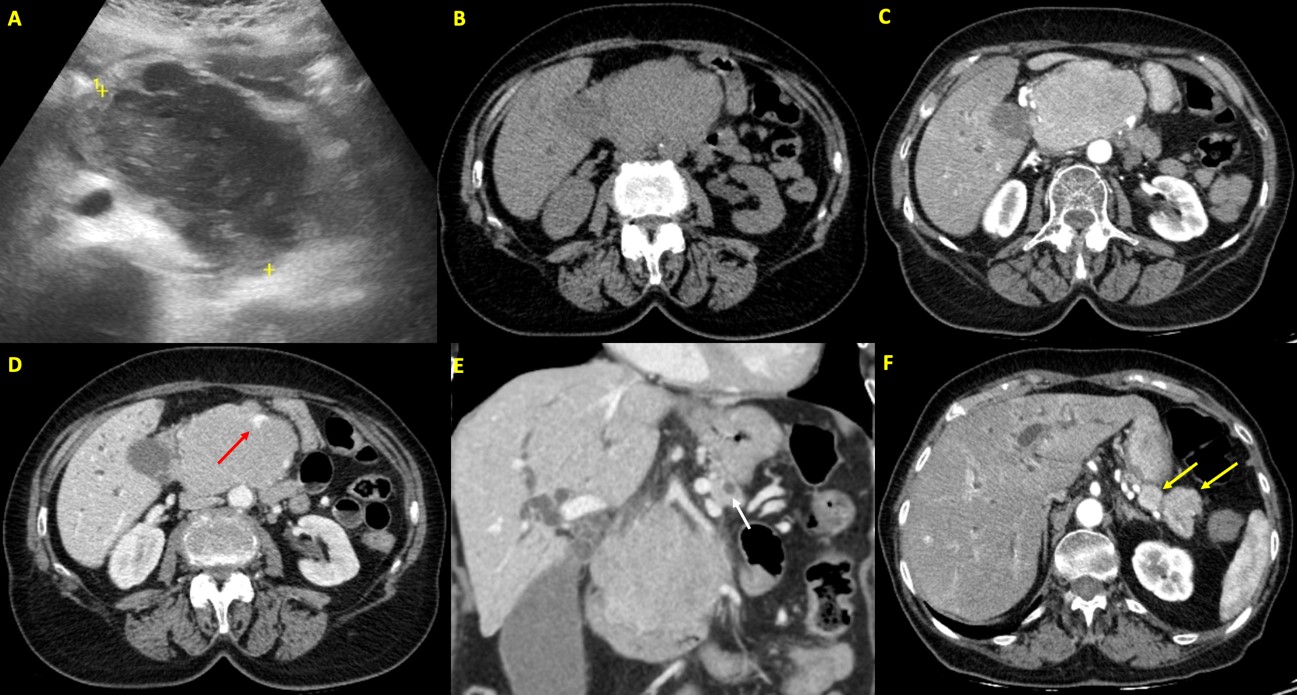

An abdominal ultrasound was performed, which revealed a large, heterogeneous and hypoechogenic mass originating from the pancreatic head, with vascularization in the color Doppler study. (Fig. 1)

In order to better characterize the ultrasound findings, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen was performed, which revealed intra and extrahepatic bile duct dilatation, conditioned by a large mass with homogeneous enhancement originating from the head of the pancreas. At the level of the pancreatic tail, at least two tumor nodules are identified with characteristics similar to the mass described in the pancreatic head. Considering the history of multiple myeloma and the homogeneous enhancement of the lesion, already evident in the arterial phase of CT, the presumptive diagnosis of pancreatic plasmacytomas was made.

An ERCP was performed which demonstrated marked extrinsic compression of the 2nd portion of the duodenum. In the first attempt to overpass the stenosis to access the papilla of Vater, a perforation of the duodenal wall occurred and the procedure was stopped. Given the patient's clinical situation and contained retroperitoneal perforation, the surgery team opted for conservative treatment.

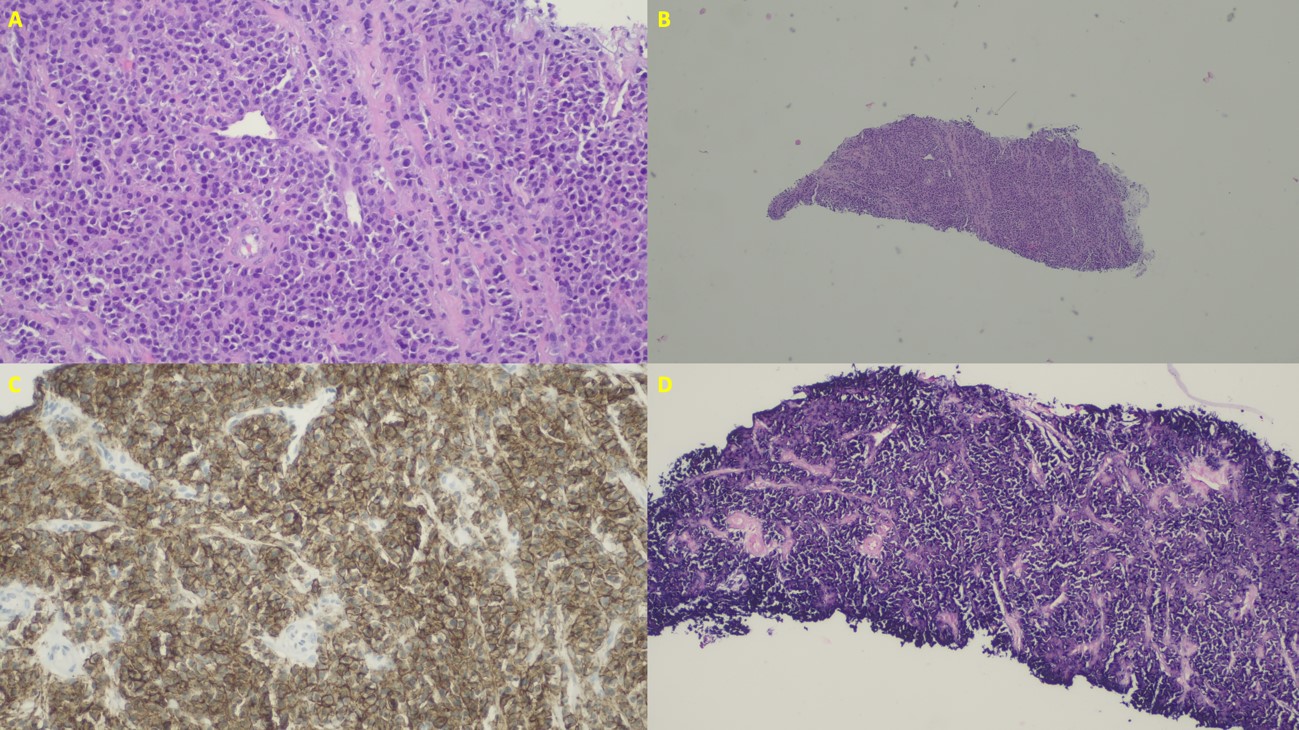

After stabilizing the patient's clinical condition, an ultrasound-guided core biopsy of the mass located in the head of pancreas was performed and histological analysis of the specimen confirmed the diagnosis of pancreatic plasmacytoma. (Fig. 2)

The patient died a week later, following a hemoperitoneum, complicated by hemorrhagic shock.

Figure 1: A. Abdominal ultrasound: Large, heterogeneous and hypoechogenic mass originating from the pancreatic head, with vascularization in the color Doppler study (not shown). This mass caused dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts and the main bile duct. B-F. Abdominal Computed Tomography - non-enhanced phase (B), arterial phase (C and F) and portal venous phase (D and E). Intra and extrahepatic bile duct dilatation (main bile duct measuring 15 mm in diameter), conditioned by a large mass with homogeneous enhancement, already evident in the arterial phase, originating from the head of the pancreas, with lobulated contours, measuring 84 x 69 x 90 mm (B, C and D). This mass also caused dilatation of the main pancreatic duct (caliber of 6 mm) and compresses the duodenal arch (E - the white arrow shows the dilated main pancreatic duct). The superior mesenteric vein is enclosed in the mass, dysmorphic, although permeable (as indicated by the red arrow in D). At the level of the pancreatic tail, at least two tumor nodules are identified with characteristics similar to the mass described in the pancreatic head, the largest measuring approximately 24 mm (as indicated by the yellow arrows in F).

Figure 2: A. Histology: Cells of plasmacytoid morphology, with eccentric nucleus. B. Histology: Fragments revealing diffuse neoplasm infiltration. C. Histology: Immunostaining for CD138 confirming the plasmatic nature of the cells. D. Histology: Restriction for lambda chains demonstrated by in situ hybridization.

Discussion/Conclusion

Extramedullary plasmacytomas are rare tumors that can occur either as primary lesions or as a manifestation of multiple myeloma.1 About 80% of the extramedullary plasmacytomas develop in the upper respiratory tract; however, other sites such as the gastrointestinal tract may also be involved. Extramedullary plasmacytomas are frequently diagnosed in advanced stages of multiple myeloma and are associated with poor prognosis.2

Pancreatic involvement by plasma cell myeloma is very rare, accounting for less than 0.1% of pancreatic masses.3 Pancreatic plasmacytomas (PPs) occurs more commonly in males than in females with a median age of diagnosis of 60-65 years.4 Most of the PPs are single lesions, however multiple concurrent lesions may occur.3 The most commonly involved site of presentation is the head of pancreas and, for this reason, the most frequent clinical presentation is through obstructive jaundice and abdominal pain.5

Radiological findings are not specific. On ultrasound, most of the lesions have been reported as hypoechoic focal masses with low-level echoes.5 On CT, these tumors appear more commonly as well-defined, multilobulated, homogeneous soft-tissue masses; they are hypoattenuating to the pancreatic parenchyma on the noncontrast-enhanced CT, while on contrast-enhanced CT, they typically enhance homogenously in the arterial phase but become isoattenuating to the pancreatic parenchyma in later phases.4 The most typical finding of PP on CT has been reported as the presence of a focal multilobulated mass with homogeneous contrast enhancement. On MRI, they are hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images, compared to normal pancreatic tissue. MR cholangiopancreatography is a very sensitive method for the detection of PP.5

Recently, the use of F18 PET/CT has been recommended.6 This imaging technique allows morphologic evaluation by CT and metabolic tumor activity by PET and is also predictive for response. As in other plasma cell tumors, moderate to intense 18F-FDG uptake is seen.5

The differential diagnosis of PP includes pancreatic adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumors, lymphoma and hypervascular secondary tumors (eg, metastasis from renal cell carcinoma). The radiological differentiation of PP from other pancreatic tumors is difficult and, for this reason, the definitive diagnosis is histological. The biopsy can be performed endoscopically (eg, EUS-guided FNA), percutaneously (eg, ultrasound-guided core biopsy) or surgically (excisional biopsy).7

Treatment of biliary obstruction secondary to PP should include endoscopic stent placement and a size reduction therapy of the pancreatic mass.3 PPs are sensitive both to radiation and chemotherapy. In secondary PP, therapeutic options include chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination of both.8 Prognosis is more favorable in primary PP than in secondary PP. The presence of extramedullary involvement in MM at any time of its evolution is associated with a more aggressive course.3

This case highlights the importance of keeping a broad differential when suspecting a pancreatic malignancy in patients with obstructive jaundice and those with a history of plasma cell tumors. In summary, in a patient with multiple myeloma and a pancreatic mass, PP should always be considered in the differential diagnosis.