Introduction

Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysms (HAP) after liver transplantation are rare, with reported incidence between 1 and 2%.1 They usually occur within the first month after transplantation and are commonly associated with localized infection.2 The mortality associated with HAP formation is high (69%), particularly if surgical intervention is performed as an emergency following acute haemorrhage.2

HAP can be classified as intrahepatic or extrahepatic according to its location. Intrahepatic pseudoaneurysms may result from previous procedures, such as liver biopsy and biliary drainage, whereas extrahepatic pseudoaneurysms are commonly associated with localized infection or anastomotic complications.2

Different treatment options exist for HAP, which include surgical resection and revascularization, radiological coil embolization or stenting and retransplantation.1

Case Report

A 56-year-old male patient presented to routine follow-up consultation 40 days after orthotopic liver transplantation from deceased donor. It was his second graft, due to failure related to ischemic cholangiopathy of the first one, implanted 9 months earlier. In the previous transplantation he developed splenic artery steal syndrome, treated successfully with splenic artery coiling.

In the second transplant, hepatic arteries and portal veins of the donor and recipient were anastomosed end-to-end and bile duct reconstruction was performed with a duct-to-duct anastomosis. Intraoperative findings showed no abnormalities in the hepatic artery, portal vein, hepatic vein or bile duct.

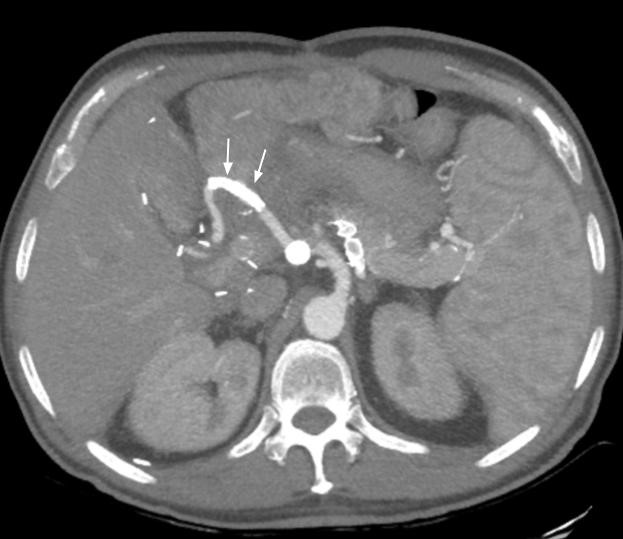

In the hepatic Doppler ultrasound, performed at the 40th day consultation, a fluid collection in the hepatic hilum was noted, apparently of vascular origin, and an urgent abdominal CT was performed. The CT showed a large HAP, measuring 3 cm in diameter, near the hepatic artery anastomosis (Figure 1).

Figure 1: HAP. Abdominal angio-CT, with MIP and VR reformatting, showing a large contrast enhancing pseudoaneurysm near the hepatic artery anastomosis (arrows in A and B). MIP - maximum intensity projection; VR - volume rendering.

The hepatic transplantation and interventional radiology teams reviewed the case and discussed the options with the patient, recommending an endovascular approach.

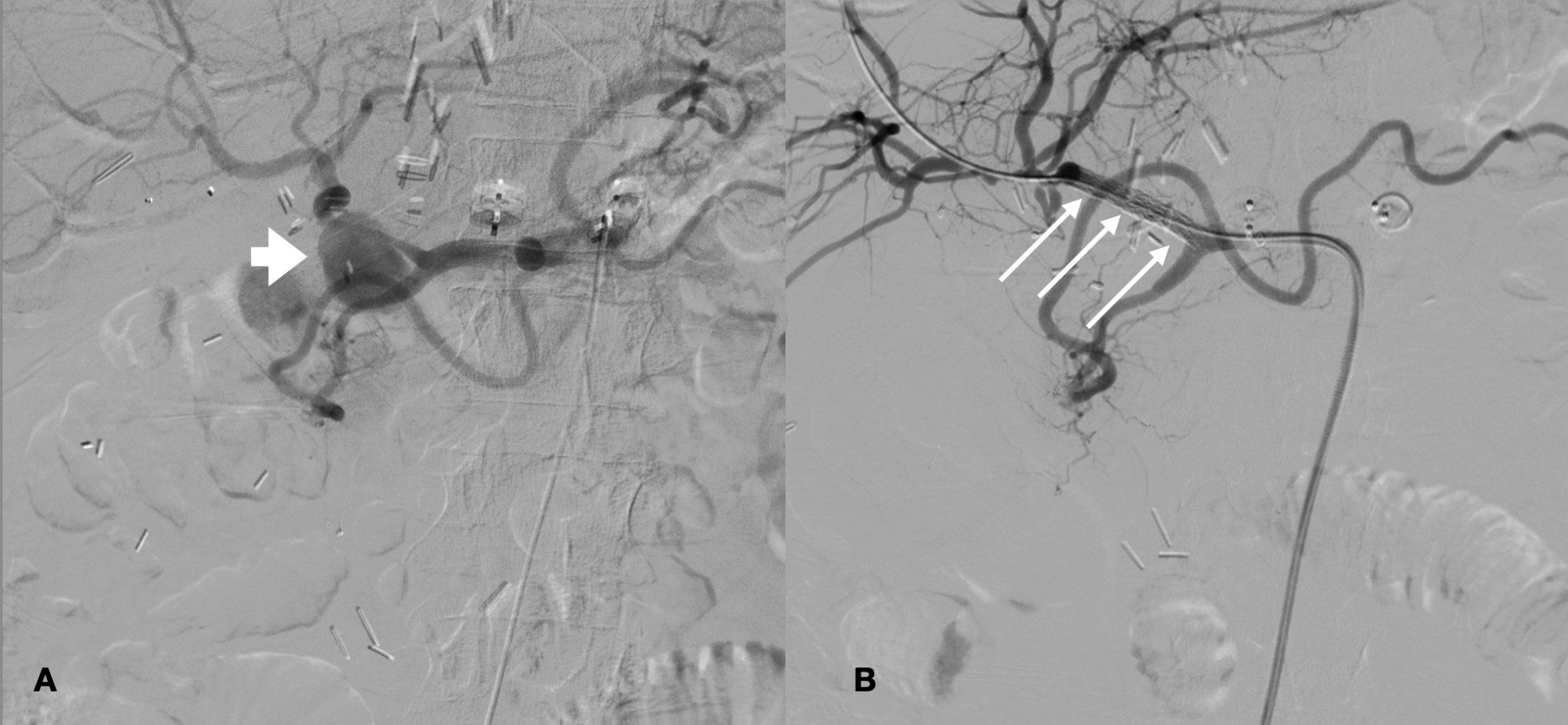

The patient was taken to the angiography lab and digital subtraction angiography (DSA) confirmed the HAP (Figure 2A). Due to the site of the HAP, and suitable anatomy (no kinking or bifurcations), a stent-grafting with 2 covered stents ( Advanta V12 ™ Balloon Expandable Covered Stent 5 x 22 mm, Getinge®, Gotemburg, Sweden) was performed (Figure 2B). First the right hepatic artery was reached with a hydrophilic guidewire (Terumo® 0,035’’ x 180 cm, Tokyo, Japan), allowing the catheterization with a 4F multipurpose catheter and the guide was replaced by a more rigid one (Starter ™ 0,035’’ x 260 cm, J tip, Boston Scientific ®, Massachusetts, USA). An introducer sheath (Destination ™ 7F, 45 cm, Terumo®, Tokyo, Japan) was then positioned at the site of the anastomosis allowing the subsequent release of the first stent graft that did not completely exclude the pseudoaneurysm. Thus, the proximal portion of the stent graft was prolonged with a second partially overlapping stent, leading to the complete exclusion of the pseudoaneurysm.

Figure 2: DSA confirming the presence of a HAP (thick arrow in A). Stent grafting with 2 Advanta V12 Balloon Expandable Covered Stents 5 x 22 mm (arrows), showing good end-result, with HAP totally excluded (B). DSA - digital subtraction angiography; HAP - hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm.

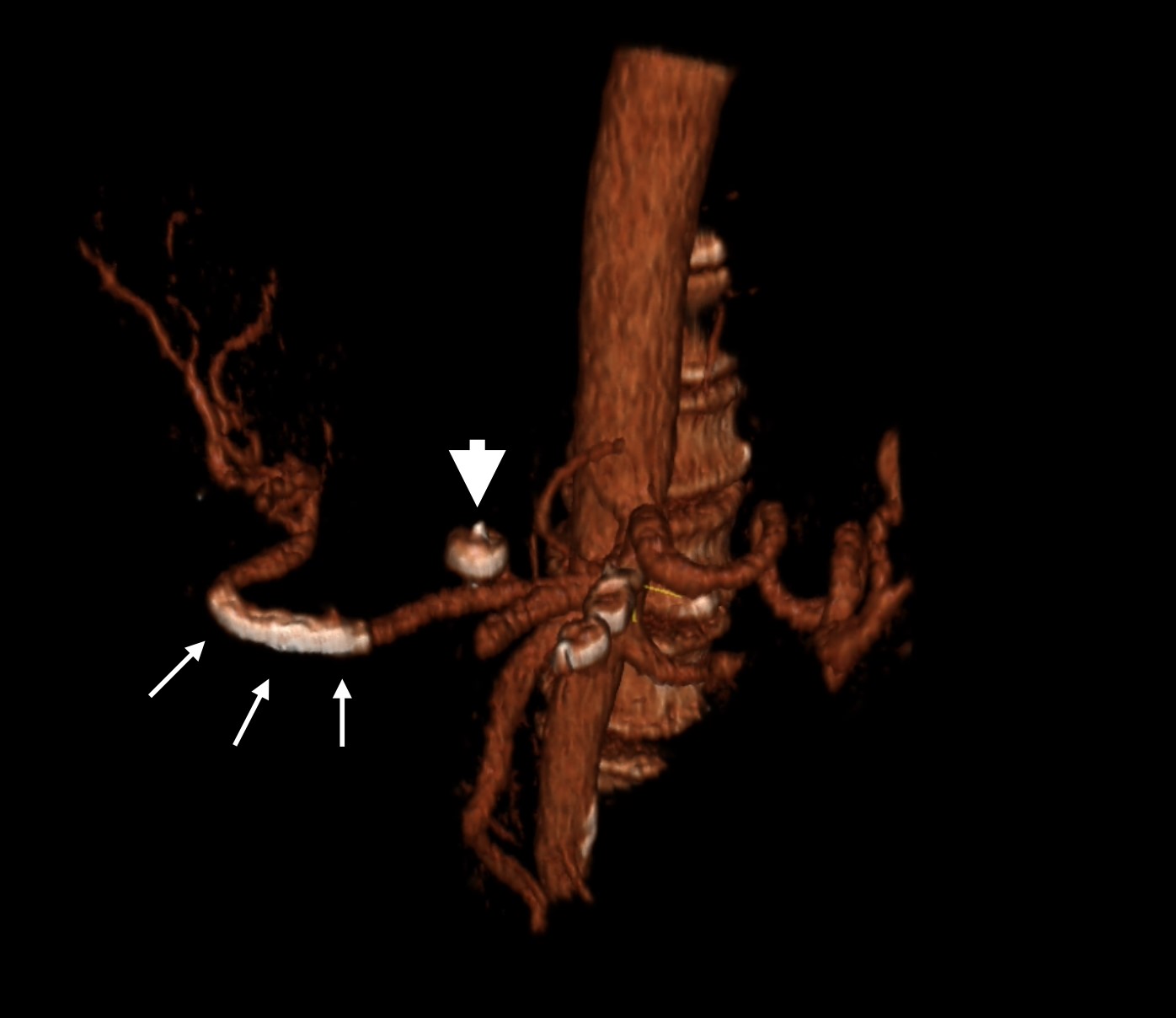

A follow-up CT performed 5 days after stent placement showed good results, with stents in place and the HAP excluded (Figure 3). Antiplatelet medication with clopidogrel (75 mg) and low-dose acetylsalicylic acid (100 mg), was maintained during the following 6 months. Presently, at 10-month follow-up the patient did not present infection or hemorrhagic complications and the stent-graft is patent (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Abdominal angio-CT, with VR reformatting, performed 5 days after the intervention, showing the stents in place (small arrows), with no thrombosis or sign of the HAP. There are also signs of previous venous embolization of a large left gastric vein with an amplatzer plug device (large arrow).

Discussion

The clinical manifestations of HAP vary from asymptomatic, to abdominal pain with fever, gastrointestinal bleeding (up to 25%) and hemorrhagic shock.1,2,3

Post-surgical surveillance ultrasound examination combined with color Doppler, has been shown to improve detection of vascular complications, with DSA still being the gold-standard imaging modality in the evaluation of an aneurysm.

Several factors have been implicated in hepatic artery complications, including: technical imperfections at the anastomosis site and type of reconstruction, intimal dissection, kinking and repeated anastomosis.1

Treatment options consist of either interventional radiology with insertion of an arterial stent or coiling at the neck of the aneurysm and surgical intervention.1,2,4,5 Superselective microcoil embolization has been recognized as an effective treatment in patients with extrahepatic pseudoaneurysms of the hepatic arteries.1,2,6 Embolization is the treatment of choice in biopsy related intrahepatic pseudoaneurysms.1

The use of covered stents has some technical difficulties, namely in tortuous vessels, such as the hepatic artery due to low flexibility of the endoprosthesis. Not all vessels are adequate for stent placing, however, some strategies can be adopted, such as using a short endoprosthesis, a stiff guidewire and a long introducer sheath. Also, some manufacturers provide more flexible stents (e.g. Gore® VIABAHN® Endoprosthesis), compatible with low profile guidewires (i.e. 0,018”), ideal for smaller and tortuous vessels or severe stenosis.

In the case we presented, the location of the HAP seemed suitable for the stents, with no kinking of the vessel. Hepatic artery patency was maintained, preserving arterial blood supply to the liver, which was of particular importance in this patient, who had already been subjected to a second graft placement after ischemic cholangiopathy. The gastroduodenal artery was also preserved, although sometimes it has to be excluded during the procedures, usually with no major consequences.

Stent graft implantation for the HAP treatment is associated with high rates of technical success and good short-term stent patency rates (81%), decreasing to 40% at mid-to-long-term follow-up.7