Case

A dependent 83-year-old female presented to the emergency department with a history of dysuria and prostration.

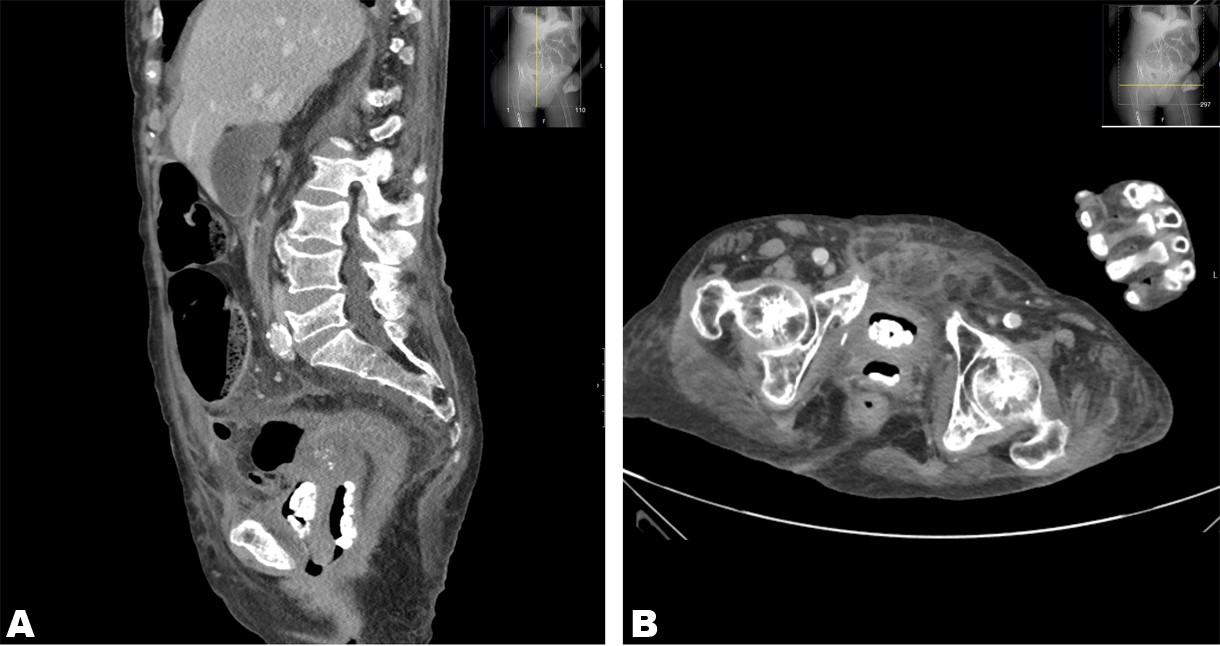

The patient had a past medical history of cervical cancer, treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy, which precipitated enterovesical and enterovaginal fistulas. No abnormal findings were noticed on physical examination. An abdominal and pelvic computed tomography CT) with intravenous contrast was performed which revealed the presence of multiple calcifications within the vagina Figure 1), surrounded by a big amount of gas, without clear evidence of vesicovaginal or urethrovaginal fistula. These findings were suggestive of primary vaginal lithiasis. Stones were also observed within the bladder Figure 1).

Discussion

Vaginal lithiasis, also known as vaginal stones or calculi, is a rare pathology that is often misdiagnosed because most clinicians do not even suspect its presence.

The formation of vaginal stones is a slow process, and most cases are only discovered when the stones are large enough to cause obvious clinical symptoms, or accidentally when an imaging exam is performed.1

Clinically, the patients could present dysuria, vaginal pain, and dyspareunia. Additionally, vaginal calculi can also cause urinary tract irritation symptoms such as frequent urination and urination urgency.1

Based on the etiology of the disease, there are 2 types of vaginal stones: primary and secondary. Primary vaginal lithiasis results from the stasis of urine within the vagina. Stagnant urine facilitates infections caused by urease-producing bacteria, such as Klebsiella, Proteus mirabilis, or Escherichia coli, so that the acidic environment of the vagina becomes alkaline, which contributes to the formation of vaginal stones. Primary vaginal lithiasis is seen in cases of congenital anomalies of the genitourinary tract, vesicovaginal or urethrovaginal fistula, trauma, ectopic ureters, previous pelvic radiotherapy, neuropathic bladder, and other causes of vaginal outlet obstruction.1,2Secondary vaginal stones result from the crystallization of urinary constituents around foreign bodies introduced into the vagina, including retained medical gauze, missed vaginal pessary, or an intrauterine contraceptive device.2

In patients suspected of having vaginal lithiasis, ultrasound and X-ray examinations of the pelvis are helpful in the establishment of the correct diagnosis. Ultrasonography can confirm the presence of stones and allow their localization in the pelvic organs.1,2When the stones are difficult to identify, it is feasible to perform a pelvic CT and magnetic resonance imaging for the correct diagnosis. In our particular case, the diagnosis was performed with the aid of a pelvic CT.

Treatment involves the complete removal of vaginal stones, either through manual extraction or surgery. Surgery is the preferred treatment, however, stone fragmentation and extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, as well as endoscopic intervention, are commonly employed techniques.3 Recurrence is only avoided if the underlying etiology is adequately addressed.

Conclusion

The diagnosis of vaginal lithiasis can be difficult and requires that the physician is highly suspicious of this possible diagnosis. As in our case, this diagnosis should be considered when urinary symptoms are present in women with physical disabilities, particularly those who are bedridden and have urinary incontinence.