Case Description

A 67-year-old non-smoker woman with a long-standing dyspnea was referred to our center due to multiple solid lung nodules suspected of metastatic disease on a computed tomography (CT). She had history of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. No other relevant past medical or drug use history, and her physical examination was unremarkable.

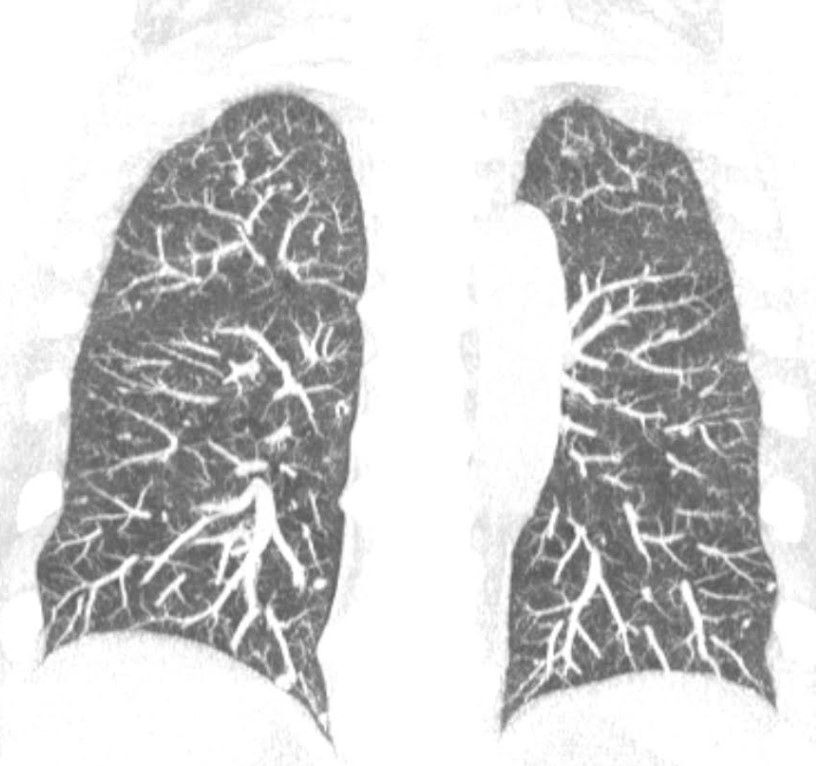

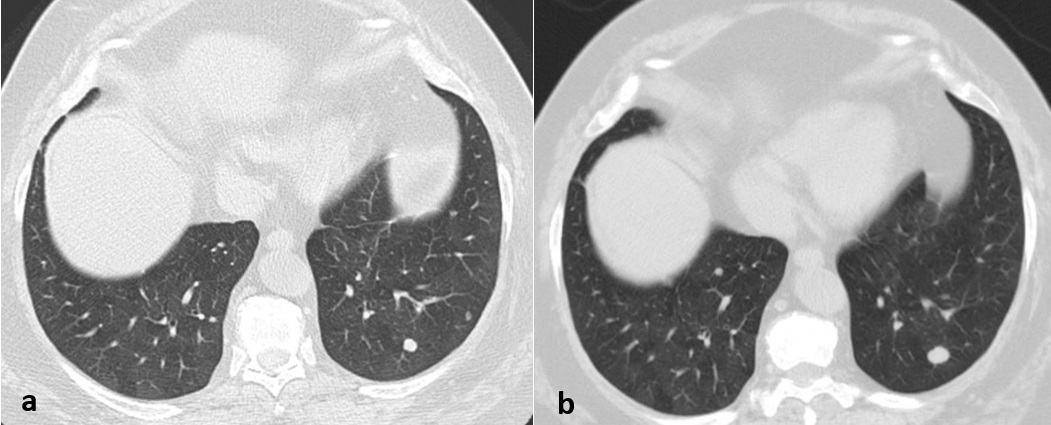

CT showed multiple small (<5mm) bronchocentric and endobronchial solid nodules, diffusely distributed but predominating in the lower lobes and peripheral zones, suggestive of metastatic dissemination (Figure 1). Mosaic attenuation was also observed in the affected areas in relation to air-trapping (Figure 2). A lower left lung nodule was subject to a core-needle biopsy and was positive for Cd56 and chromogranin, findings which were consistent with neuroendocrine cells proliferation (tumorlets). Characteristic CT findings, clinical symptoms and histology results suggested the diagnosis of diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia (DIPNECH). Spirometry showed a nonspecific ventilatory abnormality, with decreased forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) - 67.4% and 60.2% respectively, associated with severe small airway obstruction (maximal expiratory flow 75/25, 22.4% of predicted flow), without significant improvement after bronchodilation.

Figure 1: Coronal maximum intensity projection (MIP) image demonstrates numerous bilateral small nodules (<5mm) corresponding to tumorlets. MIP reformation is useful for the detection of nodules.

Figure 2: Coronal and axial minimum intensity projection (MinIP) reformations’ images demonstrate an extensive mosaic attenuation pattern with sharply defined lobular areas of low attenuation due to small airway obstruction. The usefulness of MinIP reformations for the detection of subtle mosaic perfusion must be emphasized.

Long-term surveillance was recommended. After 4 years of follow-up, the nodules remained stable, except for the previously biopsied nodule in the lower left lobe which showed an increase in size (Figure 3). This nodule was again submitted to core-needle biopsy which depicted findings compatible with typical carcinoid tumor.

Figure 3: (a) On the axial CT image, a 4 mm peripheral nodule is demonstrated in the left lower lobe, with smooth margins and solid attenuation, suggestive of a tumorlet (b) After 4 years of follow-up, this nodule showed an increase in size and was compatible with typical lung carcinoids at core biopsy. The distinction between these two is the size.

Discussion

Pulmonary neuroendocrine cells (PNECs) are epithelial cells of the bronchial wall found from the trachea to the terminal bronchioles.1 Sometimes these cells proliferate with a spectrum ranging from neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia to tumorlets to carcinoid tumors. Hyperplasia of PNECs can be idiopathic or occur secondarily to chronic hypoxia or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.2,3 Hyperplasic PNECs and peribronchiolar fibrosis can lead to constrictive bronchiolitis, which is responsible for mosaic attenuation seen in CT.4,5

DIPNECH is a rare and under-recognized disorder characterized by peribronchiolar proliferation of pulmonary neuroendocrine cells that do not extend beyond the basement membrane.3,6 It is a recognized preneoplastic condition, according to the World Health Organization, and it is more frequently associated with carcinoid tumors development than other forms of PNEC proliferation.7

When proliferation of PNECs extend beyond the basement membrane, nodular proliferation is termed tumorlets (smaller than 5mm) or carcinoid tumors (5 mm and larger).8 DIPNECH-related carcinoid tumors are usually multiple with a dominant/larger lesion almost invariably located at the lung periphery and almost always of low grade. These differ from non-related DIPNECH carcinoid tumors which in most cases are centrally located.2,9

DIPNECH affects predominantly non-smoking middle-aged women without predisposing conditions.7,9 Patients frequently present with nonspecific and progressive respiratory symptoms, such as chronic cough, asthma-like symptoms, and dyspnea.4,6,10 DIPNECH is rarely associated with systemic symptoms.5,10Diagnosis is difficult in asymptomatic patients and DIPNECH is sometimes incidentally discovered during clinical investigations for other diseases.2,3,9

DIPNECH is a potential cause of obstructive lung disease in older women, and it is frequently misdiagnosed as asthma, which leads to substantial delays until the correct diagnosis is established. Progressive functional limitation can occur, and severe cases have required a lung transplant.4,6,7,10

Pulmonary function tests (PFT) usually show an irreparable obstructive syndrome in most cases, but normal pulmonary function tests are also seen.4,11,12PFTs showed statistically significant correlations with imaging findings. The number of nodules measuring at least 5 mm showed strong inverse correlation with the percentage predicted for both FVC and FEV1 and moderate inverse correlation with total lung capacity (TLC) predicted. Mosaic attenuation showed an inverse correlation with TLC, FVC and FEV1 of predicted.6

CT findings are nonspecific for DIPNECH and are related to airway obstruction. The presence of numerous small-airway-centered nodules adjacent to centrilobular bronchioles, with a mid-lower zone predominance, associated with bronchial wall thickening and mosaic attenuation are suggestive. Lesions are almost always bilateral.6,10Mosaic attenuation is the most important and suggestive finding. Expiratory CT can help detection by demonstrating air-trapping, which may be an indirect sign of small airway obstruction.2,6,13 Extensive pulmonary fibrosis, diffuse ground-glass opacities, pleural effusions and lymphadenopathy are very unusual findings in DIPNECH.4,10

DIPNECH nodules in most cases demonstrate solid attenuation, well-defined borders, round shape and seldom calcify. Little et al found that nodules had a predominantly centrilobular distribution, often at the center of lobular air trapping.6 Nodules with spiculated margins, and cystic or cavitary components favor other etiologies.5,10Peribronchial distribution of the nodules appears to be the CT feature most predictive of DIPNECH, when associated with mosaic attenuation.5 Lung masses are rarely present in DIPNECH.4 Nodules associated with DIPNECH should not be confused with pulmonary metastatic dissemination of an extra-pulmonary neoplasm although multiple pulmonary nodules in a patient with history of cancer should be considered metastatic until proven otherwise.9,10 The peribronchiolar predominance of small nodules and air trapping in DIPNECH diverges from the usual random pattern of nodules in hematogenous metastatic disease.6 Distinction between DIPNECH and pulmonary metastases based on chest CT may not be possible and comparison with previous imaging to assess the temporal evolution of the nodules over time is necessary.5

DIPNECH has an indolent course, a rapid increase of nodules, in number and size, and is more consistent with another etiology. In the study by Little et al 67% of the patients demonstrated slow increase in size of the largest nodule after 3 years or longer of follow-up.6

A definitive diagnosis of DIPNECH always requires histopathological confirmation of diffuse neuroendocrine cell proliferation.7 Surgical lung biopsy or resection is the reference standard because it allows obtaining a larger sample, which is necessary for the correct diagnosis, although it has been suggested that a transbronchial biopsy showing PNEC proliferation could be sufficient if clinical and imaging scenarios are suggestive.10,11,12

The prognosis doesn’t seem to depend on carcinoid development but rather on the severity and progression of respiratory symptoms, which can lead to respiratory failure.7,14 Even at a metastatic stage, DIPNECH-related carcinoid tumors are not associated with poor outcome.10 Treatment of airflow obstruction related symptoms is the main objective in DIPNECH management, but response to currently employed pharmacological therapies is very limited.2,3,11

In most patients, DIPNECH remains stable over many years or progresses very slowly but can result in severe airflow limitation and respiratory failure.7 The nodules usually increase very slowly in size but close follow-up by CT of patients is essential to detect nodules that meet criteria to be classified as carcinoid tumors and routine CT surveillance every 12 to 24 months is recommended.15,16

Finally, knowledge of typical DIPNECH clinical and imaging features help to diagnose this condition and to distinguish it from other airways diseases. Radiologists may be the first to suggest a correct diagnosis and a strong imaging-based suspicion of DIPNECH can prevent an incorrect diagnosis such as metastatic dissemination which has significant negative implications for these patients. CT findings are insufficient to establish a definite diagnosis. However, mosaic attenuation pattern associated with multiple centrilobular lung nodules in a middle-aged woman referred for chronic cough or asthma-like symptoms should be a clue for DIPNECH. The diagnosis of DIPNECH is often delayed because of limited awareness of this condition and lack of familiarity with its imaging appearance which emphasizes the importance of early suspicion of DIPNECH at imaging to minimize delays and even inaccuracy in clinical diagnosis.