Case report

We present a case of a 70-year-old man with a history of generalized and intense abdominal pain, vomiting and constipation. On physical examination a right, voluminous inguinoscrotal hernia was identified. A flat, non-compressible and non-tender abdomen was present.

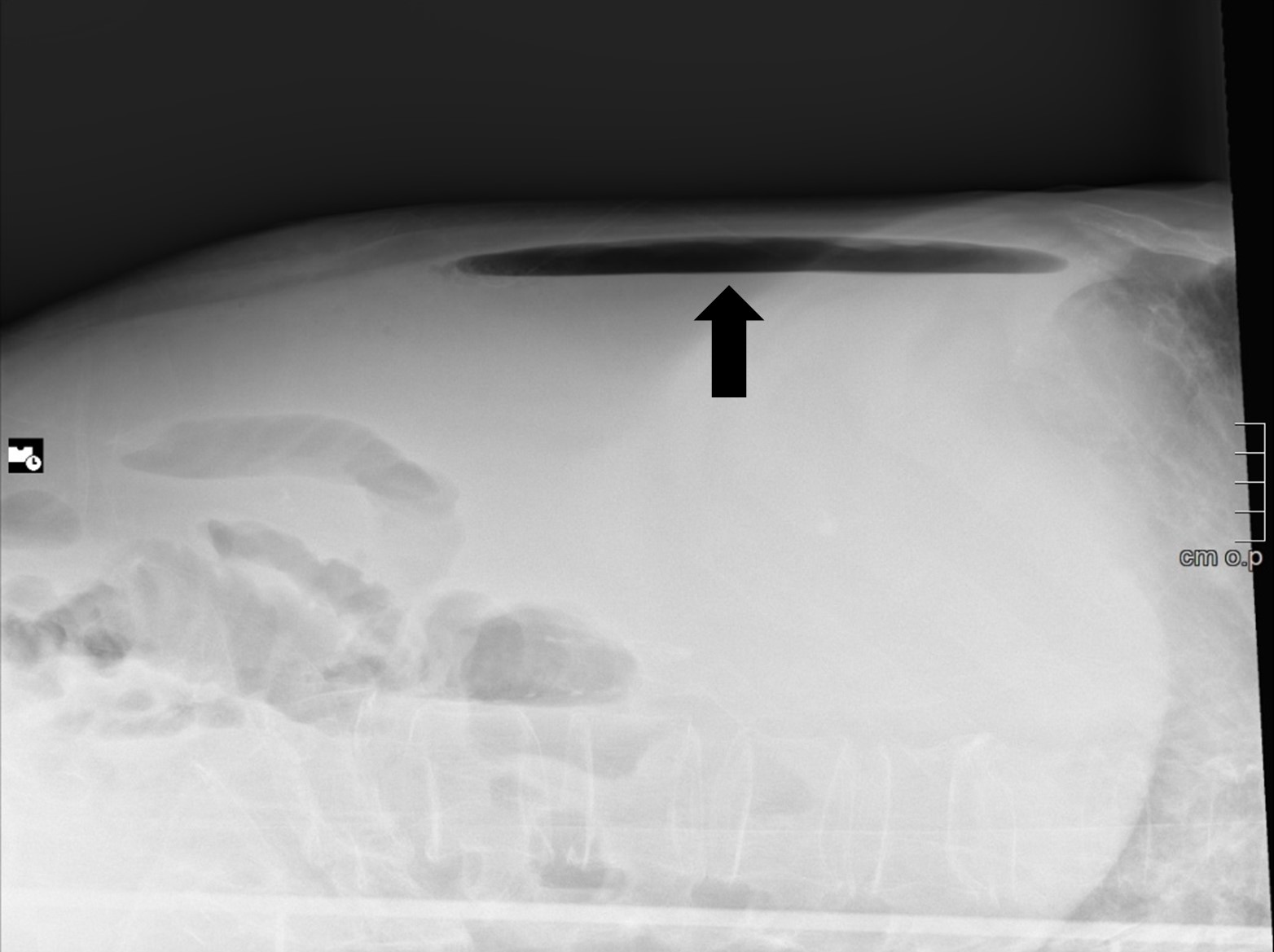

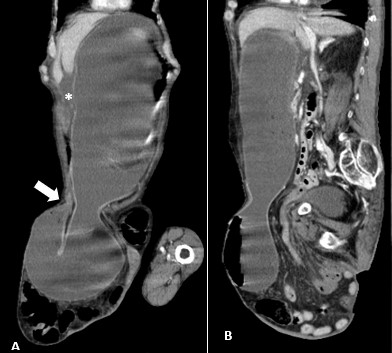

A tangential abdominal radiography was obtained, in this context, and a gas level on the non-dependent portion of the abdomen was identified (Figure 1). This finding raised the suspicion of pneumoperitoneum and, therefore, a CT was performed. On CT, a markedly distended stomach, as well as a distended oesophagus and free abdominal fluid were identified, implying an obstructive event (Figure 2). The inferior portion of the stomach and some intestinal loops were contained on the right inguinoscrotal hernia, making this the most probable cause for the obstruction (Figure 3).

Figure 1: Tangential abdominal radiograph showing an air-fluid level, that corresponded to gastric bubble (black arrow).

Figure 3: Marked gastric distension, with inferior part of gastric body herniated through inguinal hernia, and with transition point at the level of pylorus (A, white arrow). Free abdominal fluid is also present (A,*).

This patient had a poor prognosis. Therefore, a nasogastric tube was inserted, and other comfort measures were taken. The patient died within the following hours.

Discussion

Inguinal hernia is the commonest type of abdominal wall hernia and occurs above the inguinal ligament and through the inguinal canal.1 This type of hernias affects more commonly men and the majority of them are acquired. Patients often refer swelling and pain in the groin area.2 The main risk factor for hernia formation is an increased intra-abdominal pressure, that can overload the protective shutter mechanism of the inguinal canal, leading to internal ring widening.1

These hernias may contain several visceral organs, with omentum or bowel being the most commonly found.1 Strangulation in the setting of an inguinal hernia is uncommon but holds considerable mortality.1 Strangulation results from trapping of hernia contents, leading to reduced venous and lymphatic flow, and eventually reduced arterial flow, causing ischemia and necrosis of the herniated organs.2 As seen in this case, complicated inguinal hernias commonly present with pain and symptoms of intestinal obstruction.2

Very few cases have been reported of inguinal hernias containing stomach, with the most cases occurring before 1980.2 In this particular case, the inguinal hernia was causing a massive gastric distention (Figure 2), indicating a gastric obstruction outlet, impeding gastric emptying. It is thought that long-standing traction of the greater omentum in the context of a long-standing hernia may draw the stomach into the hernial sac. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was also suggested as a part of the pathogenesis of gastric herniation although very little direct evidence was found to support this theory.1

In conclusion, most inguinal hernias are asymptomatic. However, in the case of symptomatic ones, early and elective treatment, can drastically reduce the complications. When left untreated, hernias can grow in size and contents, increasing the risk of complications, as seen in this case.