Nudging as a tool: especially in the transposition of EU Directives

The concept of “nudge”

Thaler and Sunstein define nudge as “any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives.” (1) In other words, we’re speaking of the deliberate introduction of subtle, non-coercive influences into people’s decision-making to get them to make more optimal choices (2).

Nudges are being used since humankind became minimally organized. They are used by choice architects - those who have “the responsibility for organizing the context in which people make decisions” who became aware that pushing behavior in a given direction is often easier that directing people in that same direction, expecting them to comply and establishing a sanction in case they do not.

Simple examples like road divisions signaling different tracks, compasses showing you the way, or clocks showing you what time it is allow us to understand how small tricks can do the magic. Simply put, nudges are “replacements” of obligatory [or permissive] norms as a means to the end of governing and regulating human behaviour. They can come in different presentations or kinds. For instance, some nudges merely provide people with better and more comprehensible information (i.e., they operate in a way that improves the quality of rational deliberation). Examples can be seen in energy efficiency labels, nutrition facts tables or the European Standardised Information Sheet (ESIS) demanded in banking services. Others operate through psychological mechanisms whose relationship torationaldeliberation is questionable at best (i.e., nudges that exploit heuristics, reasoning and decision-making biases, and other psychological processes that operate outside of conscious awareness). One of the most common examples of this kind are nudges that exploit people’s natural tendency towards inertia - like default rules used in pension plans (when organizations automatically enroll employees in their company’s retirement savings program but allow them to opt out) and organ donation .

In any case, the success of nudges resides in the fact that they are adapted to current normal life complexity. “Make it simple” is often the showcase for nudges. Usually nudges work because they make people’s lives simpler and reduce burdens and friction and this is something of immense value in our overcrowded lives. See the cases of apps in the interaction with government, or particularly the case of short message service used to remind people of tax obligations, or, more recently, of covid certificates (3).

Grounds for nudges

Thaler and Sunstein argue that on the premise of people being bad decision makers they should be nudged in the direction of their own desired goals by orchestrating their choices so that they are more likely to do what achieves their ends (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11).Arguments sustaining the case of less-than-purely-rational behaviour are many and can be found in the literature gathered under the umbrella of behavioural economics. Basically, it is argued, humans are not perfectly rational creatures, instead they make several mistakes in thinking, in deciding and in choosing. Whether this more realistic view of human behaviour is considered as irrational behaviour or ecologically rational behaviour depends on the perspective you adopt (12) (13). Either way, the many stances in which human behaviour seems less than optimal (at least in the long run) are commonly recognised.

Full disclosure, rational persuasion and nudging

The question arises on whether we are looking at a naturalistic fallacy here. Why should people be nudged, that is, which normative (legal or moral) reasons justify nudging? This is an important question because it seems that paternalistic reasons are usually not accepted as legitimate ends in the context of rule of law. In fact, unlike traditional paternalism, which rules out choices by compulsion or adds costs to the choices by coercion, nudges simply change the presentation of the choices in such a way that people are more likely to choose options that are best for them. However, they may not even consciously realise they are being nudged - even though, we would argue, nudges are not completely devoid of consent from the people (see below “ethical problems”).

Some of the debate around nudges stems from the idea that, as opposed to other forms of communication from governments which aim directly at rational persuasion, nudges do not fully disclose themselves (14) (15). They act in subversive, mysterious ways. This is partially true - if not, their effectiveness would probably be jeopardized. Information is not directly thrown at you in the form of rules and regulations duly accompanied by sanctions showing you the costs of infringement. But this is because someone already understood that ‘transparent’ rules and regulations are usually complex, burdensome and… unknown or not fully understood.

This is to say that the traditional form of communication - which is usually considered as the right way to use people’s mandate given to its representatives - could just be a decoy for transparency. In fact, its complexity also does not allow for full understanding. But it can, some might say.

Nudging in the “lawmaker’s [or policy maker’s] challenge”

Since its first conceptualization by Thaler and Sustein in 2008 , nudges have become an essential tool in the array of discretionary tools for governing behaviour (17). We should not forget, of course, that nudging as a tool for governing behaviour is a “trial and error” process. It implicates looking at the obtained outcomes, comparing them to expected outcomes and working on the differences in order to adapt and adjust. That said, it should also not be forgotten that behaviour is context-specific and cannot always be replicated in different sets.

Nudges will not be of value in every situation and, even when they do, they may not be enough to obtain all desired outcomes. But that’s something they have in common with “command and control” regulations and regulations based on economic incentives: they will not always obtain the so-long desired effectiveness of public policies.

By adding one more tool to the policy maker’s toolkit, nudges also implicate an additional challenge, that is, the one of balancing the need, i.e., the suitability of each kind of normative interference. Can the results be obtained through a less invasive form of behavioural orientation? Will it be effective? Will it be cost-effective?

The assessment requires a case-by-case analysis in which several aspects of the substratum to be regulated have to be taken into consideration. It has to be assessed whether it is something that has already been regulated and is yet to be accomplished or if it is something new. One has to figure out why previous measures have fallen short, and, of course, there has to be a careful identification of the kind of behaviour you are trying to obtain and whether it can be obtained through any tool or not. This is something that requires realising that behavioural science has a paramount role in helping decision makers devise the suitability of each tool. Contributions from psychology, sociology, anthropology, neurosciences, genetics, can and should be applied in the task of designing public policies. In addition, a list of innovative methods from data science, machine learning and predictive analytics can also be used to enhance policy effectiveness (18) (19).

Nudges in the transposition of EU Directives

One of the biggest challenges of XXIst century lawmakers is to communicate law in an effective way. Our lives are crowded with information and normative guidance comes from multiple sources. Moreover, legislators are also politicians and the way in which citizens perceive politicians affects their willingness to abide by the rules they establish.

It is now common understanding in the European Union that the legal organization of societies has evolved beyond the mere political decision and enactment of law. It is of paramount importance to communicate rules and, more generally, goals and desired behaviours, in an effective way. Directives are a kind of instrument within the European Union legal paraphernalia that, as is well known, require member states to take further action in order to achieve particular results without dictating the means of achieving that result. As such, member states are free to assess and determine the instrument or combination of instruments that is more adequate to obtain such results (there is, of course, plenty of room for cost-benefit assessments of the most appropriate tool or combination of tools to accomplish public policy goals).

Surely there are formal constraints: according to article 112 (8) of the Portuguese Constitution, “the transposition into national legislation of legal acts from the European Union is carried out in the form of law, decree-law or, according to number 4, regional legislative decree.” But nudges can prove to be a cost-effective tool - sometimes all it takes is a little imagination and some ‘architectural’ understanding. See the cases of food presentation in cantinas, energy efficiency labels or disinfection material in the present context. Recent research that examined the cost-effectiveness of nudges and typical intervention strategies like financial incentives side-by-side found that nudges often yield particularly high returns at a low cost when it comes to boosting retirement savings, college enrollment, energy conservation, and vaccination rates (20).

The requirement of a normative source does not exclude the use of nudges. Their use can be decided in such legal instruments - for example, as a precise mandate to administrative authorities - or it can be considered in the available toolkit when discretion is attributed to such authorities.

Within the formal constraints mentioned above, nudges can be used to widen the available tools for governing behavior. They are part of a communication toolkit that has long been used by private sector companies and that is becoming usual to governments and other public institutions also in the EU.

The room for nudges in the transposition of directives should not be neglected. When transposing a Directive into national law, member states usually face a heavier communication challenge that what is implicated in national law. This is because Directives come from a larger and more distant entity whose legislator is somehow “opaque” to national citizens. The task of transposing its commands into national jurisdictions is one requiring both flexibility and imagination.

Ethical and legal problems raised by nudges

Paternalism and nudges

Notwithstanding the ubiquity of nudges in everyday life and all the benefits that their use can allow, the truth is that nudges have raised a heated discussion on their moral and legal admissibility. The first problem with nudges is their alleged paternalistic nature, as well as their manipulative force largely linked to its invariable invisibility. Put simply, are nudges paternalistic and not always fully self-disclosed? (21) The answer to this question begs another question: What exactly is paternalism?

According to Gerald Dworkin , the conditions for paternalism are the following:

X acts paternalistically towards Y by doing (omitting) Z iff:

Z(or its omission) interferes with the liberty or autonomy ofY;

Xdoes so without the consent ofY;

Xdoes so only becauseXbelievesZwill improve the welfare ofY(where this includes preventing his welfare from diminishing), or in some way promote the interests, values, or good ofY.

Disregarding now the fact that the definition of paternalism presented may itself raise some problems (23) (24), what is important to note here is that there are several arguments against nudges on the basis of paternalism. The most important are: (i) the argument of possible misuses and slippery-slopes; (ii) the argument of lack of transparency; (iii) the argument of harnessing bad reasoning; and (iv) the argument of unethical manipulation. Let us look more closely, albeit briefly, at each of these arguments.

The first argument, which is related to its possible misuses and slippery slopes, besides the fact that it depends on empirical evidence, does not constitute a general objection to nudging but to the misuse of some specific nudges , as all state action can lead to misuse; thus, as will be seen below, it is important to be able to control both the specific types of nudges and the context in which they are used, as well as the purposes for which they are used.

As to the second argument concerning the lack of transparency, on the one hand, it should be noted that the invisibility of the nudge may be necessary for its effectiveness; on the other hand, as will be seen below, the lack of transparency is an aspect that increases the intensity of the restriction, which can and should be considered, for example, at the level of judicial scrutiny; therefore, related with this last aspect, perhaps the fulfilment of some minimal transparency conditions may be sufficient to stand up to the criticism (25).

Regarding the third argument, it seems at least an extreme view to reject all forms of taking advantage of our non-rational tendencies, even for good ends - namely, those aimed at overcoming the unavoidable cognitive biases and decisional inadequacies of agents by trying to influence their decisions (in an easily reversible manner) towards the choices they would make under idealised conditions (26) -, because constitutional systems usually impose (paternalistic) duties to protect persons’ fundamental rights. Therefore, whether or not this is morally objectionable or paternalistic, the fact is that modern constitutions assign to the public authorities, for example, the duty to protect human health, the environment, or consumers .

Finally, the argument of unethical manipulation is a more complex one, which is why to be fleshed out it deserves some more attention. First of all, manipulations vary in their strength or effectiveness, which means that only paternalistic nudges that interfere with autonomy or dignity are normatively relevant. This said, the question to address is: Is manipulation always wrong? (22) (27)

Philosophers have given several answers to this question. Since it is not possible to analyse them all in detail, we can begin by noting that extreme Kantian answers according to which manipulation is always wrong should be rejected, because they would imply, for example, the wrongness of manipulating a terrorist to know where a bomb is. Having rejected these more extreme hypotheses on the tout court inadmissibility of manipulation, it seems that the best answer may well be a hybrid approach according to which manipulation (i) is sometimes prima facie wrong (perhaps whenever do not interfere with autonomy or dignity), which means that if the presumption of immorality is presumptionisdefeated, manipulation is not wrong at all; and (ii) other times it ispro tantowrong (whenever interferes with autonomy or dignity), which means other moral considerations can sometimes outweigh thepro tantowrongness of manipulation (e.g., consequences, character of agents, the badness of the desire or intention, etc.) (28).

The upshot of the foregoing analysis is that only the most extreme nudges seem to be all-things-considered objectionable on the moral ground. As in the moral domain, manipulative nudges that interfere with the autonomy and/or dignity of agents are also relevant in the legal domain. And similarly, if they are justified on constitutional grounds, they may also be permissible in the legal sphere.

Interference of nudging on autonomy, fundamental rights and human dignity

As already noted, nudges are also particularly problematic at the legal level. Specifically, nudging seems to be able to interfere with human dignity, autonomy, and more broadly with fundamental rights. A preliminary caveat on the concept of human dignity must be inserted: despite possible semantic problems with the respective normative statements, there seem to exist different and sometimes contradictory conceptions of human dignity. This explains why sometimes the concept of human dignity is pointed out as an example of an “essentially contested concept” (29) (30) (31) or deemed to instantiate “deep interpretive disagreements” (32) (33).

Having canvassed the deeply contested nature of human dignity, the fact is that constitutions and human rights charters often enshrine a principle of human dignity. Specifically, it is possible to identify at least (i) one liberal individualistic conceptions of dignity; and (ii) one communitarian-religious conceptions of dignity. According to the first type of conceptions, dignity is generally conceptualised as a Kantian prohibition of instrumentalization: In this view, respecting rational agency precludes denying adults the right to make their own decisions, even if mistaken, is to treat them simply as means to their own good, rather than as ends in themselves. According to the second type of conceptions, dignity is conceptualised as “humanity” or as a duty (or burden) to act in a certain way .

As is the case with the concept of dignity, the concept of autonomy is invariably part of modern constitutions and human rights’ charters. And even when it is not expressly foreseen in constitutional statements, the latter often enshrine a freedom to personal development, which covers “everything which is in the interest of a person’s autonomy” (34) But what exactly is the meaning of autonomy?

First, autonomy can be conceptualised as an active dispositional property of someone to conduct her own business. Specifically, on the one hand, autonomy can be envisaged as a dispositional property; on the other hand, autonomy is a categorical property: dispositional property put into effect. Unconscious, incompetent or unaware persons have disposition for autonomy but that disposition is not necessarily put into effect.

Having briefly canvassed these two constitutional concepts, one should now ask: Can nudges “infringe” autonomy and/or human dignity? First and foremost, there seems to be little doubt that rights may be infringed by nudging regulation. (35) However, the answer to this question begs the question under what conditions can a fundamental right or liberty be interfered with?

Usually, interferences of autonomy and dignity rights presuppose a reduction of the set of possibilities of action and maybe human instrumentalization. Bearing this in mind, one can return to the core of the matter: Do nudges somehow reduce or difficult human action and/or instrumentalize human beings in a relevant way?

The answer is clearly positive. In fact, presently it is widely accepted in German doctrine and case law that there is also protection against indirect or factual interferences. But this is also the case if the State issues warnings. The German Federal Constitutional Court gave special weight to the State´s authority when issuing warnings - arguing the behavioural effect may be as strong as a command(36). This is so because Member States may be tempted to circumvent or “by-pass” the constitutional framework for limitations to fundamental rights designed specifically for the purpose of limiting “command and control” measures, not “nudges”.

David Hume stated long ago, with remarkable clarity, the following:

“(…) it is certain that rights, and obligations, and property, admit of no such insensible gradation, but that man (…) is either entirely obliged to perform any action, or lies under no manner of obligation. ” (37)

With this in mind and recalling that it is possible to qualify as a nudge “any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behaviour in a predictable way without forbidding [or imposing] any options or significantly changing their economic incentive” (38), the question that must be asked is whether nudging is legally relevant to the extent it affects not the disposition for autonomy but the materialization of such autonomy, namely: (i) the belief that certain obligations exist, and (ii) the belief of what is morally correct.

In other words, the singular aspect to be stressed regarding nudges is the fact that interferences on rights are usually relevant at the action domain, while nudging operate at a logically previous moment-the mental domain.

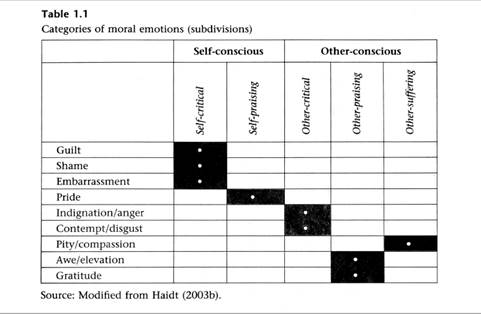

In any case, it should be borne in mind that legal norms are semantic entities expressed by legal formulations, which also entail mental phenomena (cognitive and conative attitudes) and deal with moral emotions (39). See the table below, borrowed from Jorge Moll et al. article on the Cognitive Neuroscience of Moral Emotions(40).

As it is now clear, beliefs, desires and moral emotions are the subject matter of nudges. As such, beliefs, desires and moral emotions call for “descriptive psychological questions”. Taking up Holtermann's words from a wholly different context (legal realism):

“If six year old Ellen around Christmas claims that she ought to leave some rice pudding in the addict for the Christmas pixie, we may safely assume that this is not true. We do not as a matter of fact have any duties toward imaginary creatures like Christmas pixies. If, on the other hand, Ellen’s father were to say that Ellen believes that she ought to leave rice pudding in the addict, the case is completely different. And this is so because, in contrast to the first proposition, the truth value of the latter is wholly independent of the possible existence of duties toward imaginary creatures. It depends, instead, exclusively upon whether or not Ellen actually believes in the existence of such a duty. And this is ultimately a descriptive psychological question regarding her beliefs, not a normative (i.e. norm expressive) question about the existence of duties toward Christmas pixies”. (41)

This proves extremely relevant. In fact, States not rarely have concluded that nudging may prove to be more effective at attaining a certain goal that commanding and controlling. In a nutshell, (i) if Y is the goal to be attained and (ii) X is not legally bound to Y but (iii) Nudge Z leads X to believe that Y(ing) is morally correct / prevents shame or embarrassment, then (iv) there may be sound reasons to believe that the probability that of all relevant X’s Y(ing) through Nudge Z is greater than the probability of that occurring through legally binding all relevant X’s to Y(ing).

Controlling nudges: the suitability of the principle of proportionality

Considering all problems raised by nudges and its use by public authorities, some have begun to question what legal limits apply to manipulative nudges, and the principle of proportionality appeared as an obvious candidate . However, neither the applicability of proportionality to nudges is uncontroversial, nor is it clear that it is an appropriate test. In the event that it is, it is important to see how the normative constraint provided by proportionality might work in these cases.

As seen, nudging may interfere with autonomy and dignity rights and paternalistic reasons are usually not accepted as legitimate ends, that is, as a permissible constitutional justification for restricting fundamental rights. Two initial questions immediately arise.

Firstly, which nudges are relevantly restrictive from a constitutional point of view? Some authors seem to argue that only “invisible” or “System 1” nudges interfere with autonomy, that is, those of which the decision maker is not aware of the effect of the nudge on his or her choice, because the cues are processed by the automatic “System I” of thinking . But is this a sufficient condition? For Schweizer “it is not sufficient that the decision maker is unaware of the (intended) effect of the manipulation; he or she has to be unaware of the manipulative cues - such as in the case of subliminal advertising or the subtly distorting mirrors - that one can consider the nudge an interference with personal autonomy” . At least at first glance, the author does not seem to be right. Strictly speaking, he seems to be merely identifying a concrete consideration that shows a more restrictive nudge. In a nutshell: a totally invisible nudge is necessarily more restrictive than a nudge for which only its effects are unknown.

Secondly, is there any constitutional justification that prima facie imposes or permits public authorities to create restrictive nudges? The answer is contingent, but all constitutional duties of protection and promotion of fundamental rights and liberties are good contenders (e.g., constitutional duty to protect public health, the environment or the freedom of press) . Nevertheless, even if restrictive nudges are prima facie justified from the constitutional point of view, as any other interference on fundamental rights they still have to comply with proportionality.

According to the principle of proportionality, whenever a deontic means→legal end relation is involved, public authorities are forbidden to choose deontic means that are unsuitable, unnecessary, and disproportionate in the narrow sense. In other words, proportionality control is based on assessing the proportionality qua suitability, necessity and proportionality stricto sensu of the content deontic statements (“command & control”) such as legal rules and legal decisions (42).

Given this framework, a first problem arises: being a non-formal choice architecture that alters people’s behaviour, how can be nudges be legally controlled? As stated, proportionality prohibits the choice of unsuitable, unnecessary and disproportional deontic means for the attainment of legitimate legal ends. Assuming that nudges are being used only to satisfy constitutional duties, the problem of legitimate ends dissipate because they are constitutionally justified. But as nudges are not deontic (but factual) means, does proportionality apply? To put it differently: Do nudges presuppose some deontic element that triggers the proportionality principle? As far as we can see, the answer to the conundrum is positive because there is always a decision to “nudge” (i.e., a decision with deontic content).

Therefore, on the one side, proportionality is triggered by the legal decision to nudge, which often affects not only the nudged persons but also fundamental rights of other agents (e.g., the images on tobacco packages not only aim to influence smokers behaviour, but also interfere with the economic freedom of tobacco companies). On the other side, the kind and characteristics of the nudge will be relevant for (i) the measurement of the effectiveness of the nudge used to satisfy a legitimate constitutional end (suitability) and (ii) the intensity of the interference with a certain fundamental right (necessity), as well as (iii) for the comparison of the concrete benefits of satisfying the principle justifying the nudge with the costs for the constitutional principle restricted by the nudge (proportionality stricto sensu). Let us then look at how each of the proportionality tests works by reference to nudges’ cases.

Regarding suitability, it is forbidden to choose means qua nudges that are not suitable to further the constitutional principle that constitutes the legal end to satisfy. Even if this is a test with low bite on restrictive means, because it only requires the nudge to be abstractly probable to cause the aimed end in a minimal extension, the measurement of the concrete level of effectiveness of a nudge provided by suitability can be very important in the context of the following tests, namely necessity and proportionality stricto sensu. For example, if a decision-maker is faced with a choice between a restrictive nudge with a high degree of effectiveness in achieving the same end and a legal rule with the same level of restrictive intensity but less effectiveness, necessity prohibits the choice of the legal rule.

According to the necessity test, it is forbidden to choose means qua nudges whenever there are less restrictive and at least as effective means to further the constitutional end to satisfy (43) (44) (45) (46). Regarding this second test, a first question is whether nudges qua non-coercive means are always less restrictive means than legal rules accompanied by sanctions qua coercive means . Even if they are, this obviously does not mean that excessively restrictive nudges do not exist; but their detection will be done at the level of proportionality stricto sensu. Nevertheless, one cannot rule out the possibility of using both nudging and the legal rules. In this case, the intensity of the interference is prima facie higher than to the non-cumulative use of nudges and legal rules. And what about when there are different non-coercive means? Van Aaken argues transparent nudges should be given preference . But as Schweizer underlines, this will only be the case if the transparent nudge is as effective as the invisible one .

A second question is “whether the state may actually be forced to choose a non-coercive measure over a coercive measure under this prong” . As seen, there will only be an obligation to choose a non-coercive means if an available nudge is less restrictive and as effective as the wanted coercive means. Otherwise, the public authority will have discretion as to the choice of means to satisfy the desired legal end (47) (48). But perhaps is important to take it down a notch or at least to be cautious regarding overly confident beliefs as to the effectiveness of nudges. In fact, “[w]hile early proponents were convinced that nudging is an effective way of changing behaviour, often as effective as coercive approaches, empirical evidence casts doubt on this», at least “if used in isolation” .

Finally in what regards proportionality stricto sensu, it is forbidden to choose means qua nudges whose concrete benefits are not at least comparatively of equal weight of the costs for the restricted fundamental right or freedom. Furthermore, this can be expressed in Alexy’s Law of Balancing according to puts it “[t]he greater the degree of [interference to] one right or principle, the greater must be the importance of satisfying the other” (49). In addition to different ways of formalising proportionality stricto sensu(50) (51) (52) (53), the most difficult question is to identify what considerations can contribute to justify the assignment of values to the intensity of interferences and of the importance of satisfying some constitutional principles. In other words, are there any objective facts to measure the intensity of restrictive nudges?

When one is talking about restrictive rules, substantive, temporal, territorial and subjective aspects of the interfered principle may be useful in the weighing operation (54). What about nudges? Firstly, transparency can be a criterion - the lesser the transparency of the nudge, the higher the intensity of the interference on autonomy. Secondly, the type of mental states intended to induce may also be a criterion - informative nudges are prima facie less restrictive than non-informative ones; this is related with Van Aaken’s distinction between nudges targeting the formation of preferences and nudges aimed at correcting cognitive errors in order to help people pursue their own preferences rationally . In short, it is important to identify the facts relating to the use of nudges that act as modifiers of the weight of the conflicting reasons.