1. Introduction

The health emergency caused by covid-19 has reconfigured the world of everyday life. The transformations in the labor dynamics that were about to take place ended up being implemented in various areas where, despite the efforts of governments and companies, they were progressing in a pachydermic way. In journalism, the internet and social networks had already allowed the reconversion of labor dynamics and media companies (Campos-Freire et al., 2016). The access to large amounts of data (Arcila-Calderón et al., 2016), and the use of these as sources (Renó & Renó, 2015), were normalized as strategies in the construction of media information, despite the ethical complexities that this implies (Díaz-del-Campo-Lozano & Chaparro-Domínguez, 2018).

Faced with this digital ecosystem, which challenges journalists in practice and training (López-García et al., 2017), we wonder if the mandatory confinement led to the alteration of family dynamics and the appearance of new routines and practices in this profession, specifically for women, whose low presence in the media has been proven to be linked to difficulties in reconciling their work and personal life. In his studies, Barrios and Arroyave (2007), Carreño-Malaver and Guarín-Aristizábal (2008), and Liao and Lee (2014) point out that female journalists noticed a significant difference compared to the exercise of their profession according to their marital status, emphasizing the sacrifice of their personal life and family, in front of his role as a journalist. They warned that meeting the requirements of the work and family scenario ends up affecting their mental and physical health.

Twenty-five years after the Beijing conference, improvements in the conditions of women journalists and their representation in the media have not been achieved. In Latin America, studies on women and journalism are traversed by analyzes of the under-representation of women as sources or in the process of production and circulation of information (Fernández-Chapou, 2010; Torres & Silva, 2010; Valles, 2006). The report of Comunicación e Información de la Mujer, AC (2009) pointed out that in only 10% of the news that circulates in the world’s media, women are the central focus. The voices and feminine points of view have a marginal presence. That is, there is an underrepresentation of 17%. This situation is exacerbated when the media in one country report on events that impact women in another country (Geertsema, 2009).

According to the Global Media Monitoring Project report (Macharia & Lee, 2017), women-only report 37% of the news stories in newspapers and news programs on television and radio. This figure, says the report, has not changed in 10 years, although the averages by continent fluctuate as follows: plus seven points in Africa to minus six points in Asia. From 2000 to 2015, the gap narrowed in Latin America (plus 14%) and Africa (plus 11%). The other continents registered single-digit changes, except for Asia, where the situation was unchanged. It is striking that the proportion of women reporting journalistic notes fell in all subjects except science and health, where there is proportionality.

Research on the possible feminization of journalism (Rivero-Santamarina et al., 2015) has made it clear that despite the increase in women in the faculties of information sciences, social communication, or journalism, the effective presence of these in the mass media does not compare with the number of graduates.

Women end up dedicating themselves to other professional areas with less exposure to the public sphere, thus reducing the possibility of influencing content and narratives where their voice is clear or giving a voice to other women (Mellado et al., 2007).

Therefore, there is a need for women, not only in journalism but in all professions, to take over the public sphere, overcoming the habit of “keeping them private, discreet, allowing them an open and explicit insertion in society, for joint decision-making”, (Bohórquez-Pereira et al., 2020, p. 90).

It is speculated that female journalists were hired solely to meet the needs of the market and the development of the industry in the journalistic companies of the 1990s (Liao & Lee, 2014).

About beliefs and perceptions about gender roles in journalism, de-Miguel-Pascual et al. (2019) found that subtle forms of discrimination are evident. Spanish journalists, for example, consider that their work “is constrained by business decisions, censorship, politicians and pressure groups” (p. 1829).

This article identifies the routines in which women journalists from Colombia and Venezuela have been immersed since the covid-19 health emergency. Furthermore, it determines the effects on professional practices due to the quarantines imposed by the governments of the countries where they work.

1.1. Work Routines and Practices in Journalism

Studies on news production or newsmaking were carried out in the United States from the 1970s. The empirical works and subsequent theorizations ofTuchman (1983, 1999), Wolf (1997), Molotch and Lester (1974),Bohjere (1985), McQuail (1998), and Reese and Ballinger (2001) contributed to the construction of a conceptual framework that in Latin America has had its developments in Mexico and Argentina, mainly (Stange-Marcus & Salinas-Muñoz, 2015). Other researchers such as Rodrigo-Alsina (1989), De-Fontcuberta (1993), López (1995), and Borrat (1988) have analyzed the productive routines in the media, sure that they are a direct influence on the content of the information (Retegui, 2017).

Newsmaking studies journalistic practices, differentiating them from the study of journalistic discourse. That is, it assumes production and product (the news) as two independent processes. Routine is understood as the concrete journalist’s operation in his or her individuality and journalistic practices, such as searching and collecting information concerning the sources and evaluating the event against newsworthiness criteria.

Understanding news production as a complex process and journalistic routines as a social practice imply apprehending how they dialogue and interrelate with external material factors that influence their configuration (Stange-Marcus & Salinas-Muñoz, 2015).

Benavides (2017) assumes newsmaking “as a process of construction of social reality that involves work disciplines, conceptions of time and space, ideological notions and cultural and professional habits” (p. 32).

On the other hand, when referring to routines,Retegui (2017) explains that these do not refer exclusively to the rules the style manual establishes but to internal and flexible processes that are put into use in newsrooms and tend to be modified in the face of the last-minute event. Thus, news production is complex, with diverse factors leading journalists to move between tensions/negotiations around that product.

The journalistic routine is then understood as an internalized, institutional and repetitive action and exhibits a social character since the production of the news is subject to permanent exchange and negotiation between professionals within their organizations and between the media (Stange-Marcus & Salinas-Muñoz, 2015). Then again, based on the search and collection of information, journalistic practices define the journalist’s relationship with his sources; such relationship materializes infrequent and highly institutionalized areas (McQuail, 1998).

Selecting the sources is then seen as a natural, automatic, and instinctive process based on the experience and criteria of journalists and editors. It is a skill that, little by little, they share with their peers; hence the importance of the rooms and editorial boards, since these spaces are recognized as scenarios for socialization and the exchange of positions and perspectives around a topic or event that can be considered news. Currently, the search and verification of information, two fundamental elements of journalism, are affected by the computational dimension that opens a gap between journalists with technological preparation, capable of practicing this new way of doing journalism, and those who do not have that training and are limited to perform the tasks imposed by digital media or in transition.

In this sense, the technological dimension will have more weight in journalism, which is why different journalistic currents will emerge, whose current practices are grouped as movements or specialties: multimedia journalism, data journalism, immersive journalism, or transmedia journalism (López-García et al., 2017).

1.2. Women Journalists in Latin America: Underrepresentation and Damages to Their Routines

Since the 19th century, there has been a long tradition of female presence in the media. Latin American women and writers of that century divided their time between writing and directing or participating in weeklies. The Peruvian Clorinda Matto de Turner directed El Perú Ilustrado and was ex-communed because she published a story by Brazilian Henrique Maximiano Coelho in which an earthlier Jesus appears and is interested in María Magdalena (Guardia, 2007). In his book Letras Femeninas en el Periodismo Mexicano (Female Letters in Mexican Journalism), López-Hernández (2010) makes a journey from 1873 and lists the investigations that have been developed on the subject, concluding, at the time, that the studies reach 1917 with the work carried out by Hernández-Carballido (2011) regarding the participation of women in journalism during the Mexican revolution.

On the Colombian written press, the investigations of Melo (2017),Gil-Medina (2016), Alzate (2003), and Londoño (1990) report their participation in newspapers and magazines aimed at the fair sex (as the feminine was called). However, a feminist struggle in the current sense of the word did not develop, but it made a significant contribution to raising awareness about the condition of women. Similar processes stand out in Mexico (Lever-Montoya, 2013), where women journalists face obstacles in joining the national media after working in their own or someone else’s newspapers.

In Venezuela, for example, monitoring the presence of women in the press has Joaquina Sánchez, who is actively involved with the media, after acting in politics, as a reference (Ramón-Vaello, 1985). El Rayo Azul, a literary weekly produced in 1864 in the state of Zulia and edited by Perfecto Jiménez, is identified as the first to initiate women into journalism by accepting female collaborations. The Venezuelan women had probably already participated in the national press, but no data was found before the Zulia weekly.

Finally, there are difficulties in tracking the presence of women journalists between the 1930s and 1980s in Latin America. In Colombia, the study by Carreño-Malaver and Guarín-Aristizábal (2008) identified the position, origin, and journalistic practices of women in Colombia from the second half of the 20th century to the first decade of the 21st century. They found that the practices and routines of journalists are affected by the myth of beauty, motherhood, marriage, and bullying by bosses, colleagues, or sources. Becoming a mother, for example, is a process that affects the professional life of any worker with very demanding schedules, but in journalism, it can become an obstacle.

Their study revealed the existence of tensions in the relationship between gender, journalist, and source, since “the strategy of seduction, understood as a way to captivate and gain trust, is a weapon that depending on the journalist, can help in the search for the information” (Carreño-Malaver & Guarín-Aristizábal, 2008, p. 84). In this same sense, the Fundación para la Libertad de Prensa, through the investigation carried out with journalists in various regions of the country, found that 40% of the women consulted manifested differential treatment in journalism due to their gender (Jules, 2017).

Regarding the effects on journalistic routines in male and female professionals for three Latin American countries, Gutiérrez Atala et al. (2015) determined that both in Chile, Colombia and Argentina, the transformations and vicissitudes interfere in their work and constrain their professional performance, limiting the expected social role in a democratic system.

In Ecuador, Rosales and Barredo (2014) found that in 62% of women surveyed suffered harassment, the figure “reflects a type of structural violence in women ‘s journalism in the city” (p. 93). Regarding sports journalist women in Quito, Cevallos-Rueda (2019) noted that their routines are conditioned by ideological, hierarchical, labor issues, and social pressure. To save them, they care about continuous and self-taught training, reading books, other news, and the use of social networks.

For its part,Retegui (2018) found that the participation rate of women in Grupo Clarín’s (largest media conglomerate in Argentina) processes is as follows: 13.3% of women hold a managerial position at Clarín/Agea. In the news department (Clarín/Artear), only 10% of the journalists are editors, this being a middle-ranking position since it is behind the section chiefs. However, the scenario improves for heads and executive productions in the news since women manage 20% of these areas. Despite this figure, it was determined that 67% of the graphic journalistic sector is found in sections or soft products, areas understood as having a lower editorial hierarchy, and/or where themes of tradition to the female domain are addressed.

In turn, Amado (2017) determined that journalists have minority participation in Argentine media, although newspapers promote more egalitarian plants than television, for example.

Cepeda (2020), in his study on the situation of journalists in Tamaulipas, Mexico, found that the flexibility that women require to practice journalism, be mothers, and climb the job ladder does not exist in the media structures of the newsrooms. The precarious wage adds to this. In his research, he found that the wages of women journalists are between 1.8 and 2.5 times and less than those of their US peers, although they work more hours or have graduate degrees.

Added to this, in Latin America, these professionals also face the risks of threats and deaths. Although it is clear that the homicide rate has reflected regional violence perpetrated against young men and urban contexts, there are warnings about the increased femicide and pressures to journalists (De-Frutos, 2016). Furthermore, the attacks on them are usually related to other series of legal, socio-cultural aspects and not to the exercise of their profession.

2. Methodology

This article aims to identify the routines women journalists from Colombia and Venezuela have been immersed in during the covid-19 health emergency and determine the impacts of the quarantines imposed by governments in the countries where they work in their professional practices.

2.1. Type of Research

For the development of this research, the quantitative approach was used at a descriptive cross-sectional level (Hernández-Sampiere et al., 2010) since the data is collected directly from the primary source without the researchers performing manipulation processes on them. The provision of the data occurs within a period between 60 and 80 days after the mandatory preventive isolation in Colombia begins. Finally, descriptive statistics are used to characterize the variables under study as well as possible.

2.2. Population and Sample

The population is made up of all women journalists from Colombia and Venezuela1. Non-probability sampling is implemented for the conformation with the sample. The procedure followed by the researchers to collect the data was as follows:

The link to access the survey was sent via email, accompanied by a message explaining the motivations for the investigative process, and the informants were invited to fill out the format.

This email was sent to the official addresses of: Círculo de Periodistas de Bogotá; Red de Radios Universitarias de Colombia; Red de Emisoras Comunitarias de Norte de Santander; Círculo de Periodistas de Norte de Santander; Colegio Nacional de Periodistas de Venezuela and Círculo de Periodistas de El Táchira2.

The time window for data collection was kept at 20 calendar days, reaching 110 completed surveys, and that amount corresponds to the sample size.

2.3. An Instrument for Data Collection

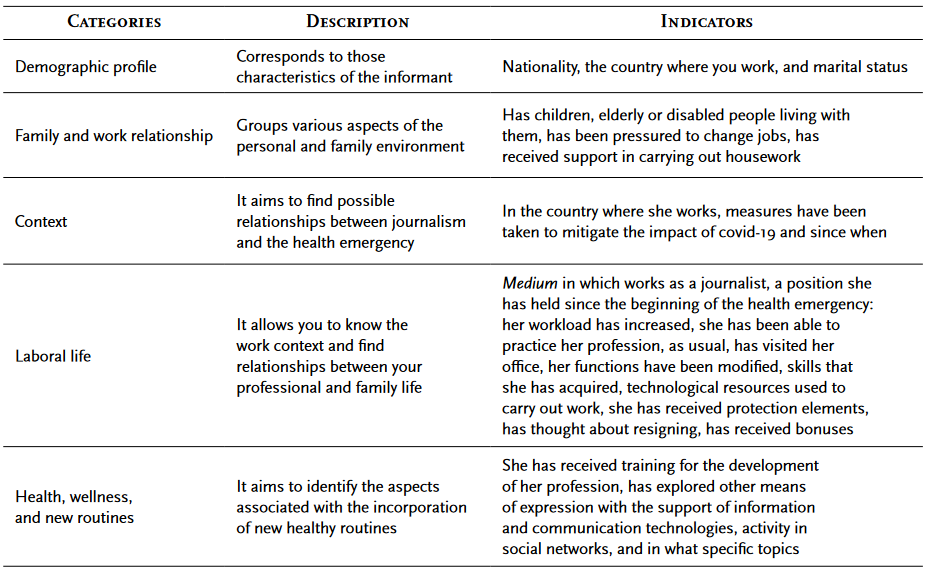

As for data collection, the survey was used as a suggested instrument for diagnostic characterization in social studies (Falcón et al., 2019). The instrument had 26 items distributed in five categories described in Table 1.

Since the researchers proposed the instrument, expert judgment used content validation (Bohrnstedt, 1976). A panel of five people was formed, three social communicators and two experts in statistics. During three 2-hour sessions, the panel members analyzed each of the categories to be measured and their indicators, reviewing the wording of each item together with the possible response options.

2.4. Procedure and Data Analysis

Once the observation window for data collection had been completed, the Google form’s Excel file was downloaded. The data were reviewed in search of possible anomalous responses to be later coded and exported to SPSS version 25. Software in which the respective statistical analyzes were carried out.

3. Results and Discussion

Regarding the demographic profile, 73% of the informants are of Colombian nationality and in Colombia, while 26% are of Venezuelan nationality practicing the profession in Venezuela, Chile, the United States, Peru, and India. The remaining 1% are native and practice their profession in their country, from Honduras or Argentina.

The percentage difference between the respondents from Colombia and Venezuela is associated with the distrust among Venezuelan journalists, who still reside in their country, to answer questionnaires about their private and work life. There are fears of being linked to the opposition and being sanctioned by the regime or vice versa. In fact, of that 23% who agreed to participate in the research, the percentage of Venezuelans practicing abroad is 50%.

To marital status, it is highlighted that 55% are single, while 25% are married, and 15% live in the common law. The remaining percentage are separated, and one of them is a widow. Faced with the majority of single women, Liao and Lee (2014) found in their study carried out in Hong Kong single women journalists and recognized for their strong commitment to professional ethics. That confirms the complexity professionals are immersed in when building a family life in Colombia, Venezuela, and China.

Regarding the family and work relationship, 42 affirm that they are responsible for one or two minor children, but 34 of them have at least one older adult under their guardianship, and five say that they are also responsible for the needs of a person with a disability.

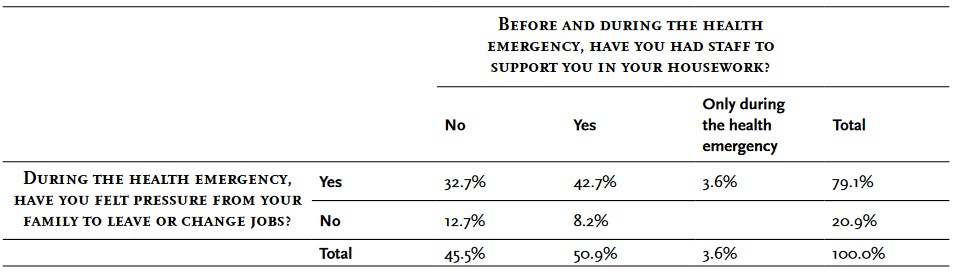

From Table 2, it can be highlighted that approximately 21% of the informants state that during the health emergency, they have not received pressure from their family to leave or change jobs, even though 13% of them have not had support for the performance of household chores. The remaining 79% have received pressure from the family to exercise their work, although 43% have had support personnel to carry out the housework.

In this sense, Lobo et al. (2017) found in their research with Portuguese journalists that, despite the normalized belief of gender balance in newsrooms, the truth is that women journalists find restrictions when managing demands family and work, on account of working hours and activities of the profession.

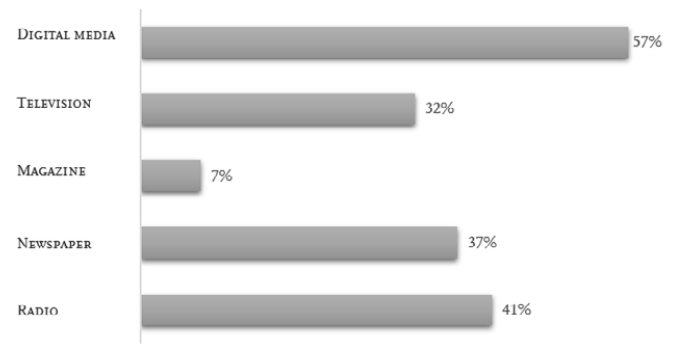

Regarding working life, it was identified that the media with the highest female performance are digital, followed by radio and newspapers. The web portal stands out regarding virtual media, followed by virtual radio and television broadcast on social networks.

Those who concentrate their work on the radio are in the public interest media that correspond to the stations of universities, government institutions, and police and military forces in Colombia. Professionals who work in newspapers divide their work into print and digital, given the migration of the media, but with double responsibility for journalists.

Finally, 19% of the informants affirm that their work activities focus on managing institutional portals and communication media of non-governmental organizations or universities. Others perform teaching functions, and some create content for independent or specialized media.

When inquiring about the position they occupy in the companies where they work, it was determined that 72% assume journalistic functions, 11% are directors, 5% are editors, and the remaining percentage occupy other roles such as communications analyst, coordinator of digital projects, head of press and protocol, announcer, presenter or producer.

When determining the effects derived from compulsory social isolation, 76% of the informants maintain that during this time of health emergency, the workload has increased, an aspect that has been reflected in the increase in the number of hours needed to carry out their work, where 29% have required between 1 and 3 hours, while the remaining percentage say that daily they demand more than 3 additional hours of work.

In this line of analysis, many work activities have had to migrate to the option of teleworking as a result of compulsory social isolation, and journalism has not been the exception. Inquired about this issue, approximately 83% of the informants recognize that the health emergency forced them to this job option, and 60% of them have not returned to their jobs since the pandemic, which affected their work functions, and 43% of them had to adjust.

The previous manifested in the increased number of sources to cover while adding tasks such as making videos, taking photographs, and designing infographics, among the most relevant and common activities. Three cases state that they were demoted from their positions, while in four cases, they affirm that necessity contributed to their promotion.

It is evident that, when switching to the telework option, many of the tasks carried out acquired more significant influence from information and communication technologies since digital media were used for content communication. For this reason, the informants were asked about the skills they had to acquire to carry out their activities during this period of the health emergency, highlighting in 90% of the cases the use of the various platforms with their respective applications, followed by graphic design and websites, among the most prominent. In this sense, women journalists from Colombia and Venezuela who had not leaped into the digital ecosystem ventured into this scenario, putting themselves in tune with international trends and accepting the transformations.

As proposed by Renó and Renó (2015), these transformations occur in the dynamics of the construction of the journalistic discourse: language, processes, relationship with sources (social networks), and a new newsroom. Other skills developed on behalf of covid-19, but less frequently, are audio and video editing, technical support of broadcast equipment, design of strategies, and virtual campaigns or live coverage.

According to López-García et al. (2017), the current journalist is required to have a versatile profile that includes from the use and management of social networks, the business management of their company (Campos-Freire et al., 2016), or the mastery of technological tools for the construction of narratives that lead to innovative newsrooms typical of the mobile communication revolution.

In the practice of journalism, the search for information from various sources is standard. Due to the declaration of mandatory social isolation, crowds of people were prohibited, and many activities were reduced to groups of five attendees. Informants were asked if their sources refused to carry out face-to-face interviews in this search for information, determining that in 8% of the cases, this situation has occurred, mainly government authorities, public figures, or health professionals who have refused to carry them out in person.

Furthermore, 30% say that in the development of their functions, they do not need to go to sources, while 61% argue that the interviews are carried out by phone or through virtual channels such as WhatsApp, Meet, Zoom, Skype, Facebook Live or Hangout among the most used.

At the beginning of the mandatory social isolation, many companies sent their workers on vacation to mitigate the economic effect of this measure. The informants were asked if they had had days of rest in this period of a health emergency before which 54% affirmed that they had had the usual days of rest. In contrast, in the remaining percentage, the opinions were divided. Some affirmed they had enjoyed more days than usual (12% of the cases), others say they have fewer days (18% of the cases), and 16% of them affirm they have had to work without rest during all this time.

The employers’ commitment was to provide their workers with the necessary protection elements to avoid the spread of covid-19. Moreover, 40% of the informants affirm that they have received supplies from them such as gloves, face masks, masks, antibacterial gel, and in sporadic cases, antiseptic alcohol or a digital thermometer; While of the remaining 60% who did not receive them, 50% claim to have bought them with their resources, while 10% have given them as gifts.

Advancing in the informants working conditions analysis in this time of health emergency, approximately 30% of them have thought about quitting their job at this time. In comparison, the remaining 70% say that resigning would not be an option, and with greater determination, 9% of them say that they have benefited from additional bonuses for their work performance during these difficult times.

Finally, when inquiring among the informants if they felt fear of being infected by covid-19 during their work functions, 57% state that they have this fear in contrast to 43% who are sure that this cannot happen. They mainly comply with the prevention indications, such as not leaving the house or using all protective implements if they must go out. It is worth noting that journalism has always been assumed as a high-risk profession (De-Frutos, 2016).

3.1. Health, Wellness, and New Routines

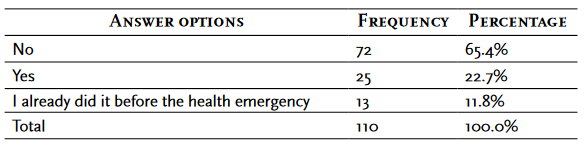

The interest in knowing the aspects of health training and if it has incorporated new media routines related to this topic led to the determination that approximately 65% of the informants have not considered entering as a youtuber, instagrammer, or blogger as a complement to their activity conventional labor (Table 3).

Those who affirmed that they have ventured as youtubers, instagrammers, or bloggers have thought about a diverse range of topics: cooking, care of children or pets, environmental movements, health and well-being, makeup, healthy lifestyle habits, among others. According to Liao and Lee (2014), this situation explores how some journalists perceive specific topics as exclusive to women because they value their femininity.

To be able to relate the journalistic exercise with the measures implemented during the health emergency. When inquiring among the informants whether the countries where they work had implemented measures to mitigate the impact of covid-19, it was determined that the response was positive in all cases. There was a diversity of opinions in the implementation of these measures. For example, Colombia is the first country to start these contingency measures, followed by Peru, India, Venezuela, and the United States.

Concerning training about covid-19 and its implications on their work, 70% affirm that they have not received any information (Table 4).

Those who claim to have received training on covid-19 have had all kinds of sources of information and instruction, the most notable being the insurer of occupational risks, digital media, or training generated by the Ministry of Health. According to the results of a survey carried out by Red Colombiana de Periodistas con Visión de Género (Red Internacional de Periodistas con Visión de Género - RIPVG, 2020), when asked if, during the health emergency, they had suffered physical or mental health problems, 50% of the respondents admitted physical complications and the other 50%, that mental.

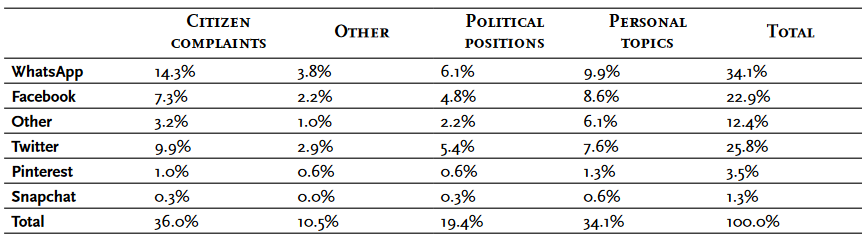

When asked if they had become more active in social networks (Table 5), 100% affirmed they did. They claim to spend more time reviewing and publishing the status of WhatsApp, Facebook, or Twitter, on personal issues, complaints about citizens, or manifestation of political positions. However, issues such as mental health states or the promotion and prevention of covid-19 arise less frequently.

According toRenó and Renó (2015), the use of social networks enables journalists of the 21st century to discover various information, which before they had no possibility of access unless it was revealed directly by the source, and homologate the fact of working without social networks to do it without a typewriter in the 40s of the 20th century. Furthermore, women journalists find the possibility of publishing information that has no place in the media where they work in personal social networks. In his study, Mojica-Acevedo et al. (2019) on women journalists as opinion leaders concluded that they allow them to deliver information in a more agile way and from their position. Thus, they enable the debate and summon their audiences to participate in various issues, especially equity and gender.

4. Conclusions

The results allow us to affirm that the health emergency caused by covid-19 has transformed the professional routines and practices of women journalists in Colombia and Venezuela, directly affecting the number of hours (between 9 and 13 hours a day), but did not represent a salary increase. This situation has generated family tensions since, to the professional practice, confinement adds the direct and permanent care of children, the elderly, or people with a disability in charge. However, resigning is not an option for these professionals, even though they have suffered family pressure to leave their jobs.

There are no positive actions by journalistic companies to promote equality or gender equity within them. Instead, the results conclude the deepening of these inequalities in terms of workload due to the increased number of sources assigned. However, the study reveals that women journalists have taken advantage of social networks and instant messaging applications to express their opinions on issues such as corruption and citizen complaints, which has opened up the possibility of interacting in channels other than their communication media. Thus, they give greater visibility to their voices and configure spaces for the generation of public opinion, which are restricted to them in the exercise of their journalistic work.

The health emergency has also caused the need to acquire more digital skills not to be left out of the labor market. Women journalists ventured into the use of platforms and applications to find information and graphic design to circulate it, which reiterates the urgency of the transformation of curricula and the construction of new graduate profiles in communication programs and faculties and Journalism, as well as the development of competencies for multidisciplinary dialogue, allows them to move in diverse and flexible but remote, information production circuits.

Confinement and the impossibility of accessing sources personally transformed access to information in the Colombian and Venezuelan context, which hastened the development of new practices within journalism that had already been found with social networks and big data in other countries. Nevertheless, this practice will require an ethical exercise in collecting information. In the digital or information and communication technology mediated process, it remains in official sources or circulates on the network, leaving direct contact with the protagonists out of the facts, ordinary citizens, as well as journalistic investigation through immersion or observation of the surroundings, necessary, for example, for the chronicle and the report.

The women journalists reported that they did not return to the newsrooms during confinement, although mobility restrictions excluded journalists in both countries. It worries then, that is outside the context of the newsroom where learning about practices and tensions is given in the face of closing hours, organizational processes of journalistic companies, and relationships with editors and bosses, one is facing the appearance of a new relational ecosystem that they were already facing, freelancers, for example. The information production process will undergo transformations that will push journalistic ethics to the limit.

We are facing one of the most significant changes in modern journalism. Will post-covid-19 journalism be a process where individuality in the production of information (typical of routines) will take on new meaning? Where perhaps there is greater polarization, less consensus, but also less organizational tensions?

texto em

texto em