1. Introduction

Architecture, as a tangible expression of an organization’s identity, is not limited to its operational function but becomes a narrative element that communicates values, traditions, and aspirations. In corporate branding, built spaces play a fundamental role as symbolic tools that express an institution’s identity and influence the perception of both internal and external audiences (Kirby & Kent, 2010).

This study contributes to the field of communication sciences by analyzing how architecture functions as a strategic tool in institutional communication. It draws on the theoretical frameworks of corporate identity and brand heritage, particularly the heritage quotient (HQ) model. While this model has been primarily applied to corporate and commercial brands, this study is among the first to use it in the university context. In doing so, it provides a new analytical perspective on how architectural heritage contributes to the construction of institutional identity. Although grounded in specific cases, the research addresses a universal issue in communication sciences: how built environments convey symbolic meaning, reinforce legitimacy, and support brand differentiation across diverse institutional settings.

In this context, the relationship between corporate identity and architecture is based on the physical space’s ability to materialize and communicate an organization’s core values (Foroudi et al., 2019). As Olins (1991, 2008) explains, physical space is one of the key vectors in brand construction, particularly in hotels, museums, and universities. In the university sphere, this connection is especially relevant: buildings not only host academic activities but also symbolize a historical legacy and project a vision for the future.

This study closely examines how universities - particularly those designated as “UNESCO World Heritage Sites” - convey their institutional identity through audiovisual communication. Institutional videos, understood as communicative products designed by the institutions themselves, aim to express their cultural and heritage narrative in an accessible and visual format. Specifically, the study analyses the representation of heritage elements (history, trajectory, legacy, symbols, etc.), with a particular emphasis on architecture as one of the most notable tools for communicating continuity, legitimacy, and institutional values.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Architecture as an Element of Corporate Identity

Architecture is not only a means of communication but also the communicated content and the meeting point for a community that interprets and inhabits it. Buildings can be seen as shared places for those who engage with them because, as they function as cultural devices that “constitute a community around them, serve as a medium of communication for that community, and ultimately represent the content being shared” (Abellán-García Barrio, 2023, p. 224).

From this perspective, institutional buildings become cultural devices that generate a dynamic interaction between the organization and its audiences. Thus, architecture articulates a shared identity while also reflecting and shaping the social and cultural environment in which the institution operates.

We will now justify how architecture is a key component of corporate identity, not only in its tangible dimension but also as a dynamic institutional narrative. To do so, we draw on branding and corporate identity theories, which position architecture as a tangible representation of an organization’s values and identity. Corporate identity is a multidimensional construct that articulates an organization’s essence, allowing it to project its mission, values, and aspirations to internal and external audiences. Corporate identity is built on three fundamental dimensions (Balmer & Gray, 2003):

Corporate philosophy: integrates the values, mission, and vision that form the organization’s core;

Communication: projects identity through coherent and consistent messages, shaping public perception;

Visual identity: represents the tangible expression of an organization’s identity, where architecture plays a central role in transforming abstract values into visual and sensory experiences.

Additionally, Balmer and Gray (2003) introduce the C2ITE model, which structures identity into five key dimensions:

Cultural: the historical roots and internal subcultures of the organization;

Intricate: the multidisciplinary complexity of identity;

Tangible: the physical manifestation of values, where architecture plays a leading role;

Ethereal: the emotional and symbolic perceptions associated with the brand;

Engagement: the active participation of stakeholders in consolidating identity.

2.2. Heritage Brands

In the field of corporate branding, historical references play a crucial role in shaping an organization’s identity. Blombäck and Brunninge (2009) note that institutions actively incorporate historical elements into their communications to project values such as continuity, stability, and trust, which influence their perceived image among audiences. These references can be expressed through narratives about people, events, or tangible symbols such as architecture. In this way, architecture becomes an effective means of mitigating the liabilities of newness (Blombäck & Brunninge, 2009), granting the organization a perception of longevity and legitimacy that strengthens public trust.

At this point, the distinction between history and heritage, proposed by Lowenthal (1985), is key to understanding how brand heritage can act as a strategic resource. While history explores the past, heritage clarifies and projects it into the present and future.

Applied to the university setting, institutional architecture emerges as a narrative tool. This function is linked to branding theories developed by Urde et al. (2007), who integrate architecture into the tangible dimensions of corporate identity in their HQ model. This model provides an analytical framework for understanding how institutional heritage materializes and evolves over time. It identifies five essential elements in heritage brands:

Trajectory: representation of historical achievements and institutional milestones;

Longevity: continuity of principles and values that convey intergenerational stability;

Core values: strategic principles guiding organizational decisions;

Symbols: tangible elements such as architecture, logos, and emblems that visually communicate identity;

History as identity: the active integration of the past as a central part of the organizational narrative.

2.3. University and Architecture: “Knowledge Can Fill a Room, but Takes Up No Space”

“University architecture” can be understood as a cultural device, a tangible artifact that integrates material and expressive elements to convey a program, a path, or even a reading agreement to those who inhabit or interpret it (Abellán-García Barrio, 2023). As previously mentioned, university buildings are much more than functional structures; they represent the materialization of intellectual, cultural, and social aspirations (Forgan, 1989), always in dialogue with the historical, political, and stylistic context in which they were conceived (Coulson et al., 2014). A brief overview of university architecture demonstrates this.

The relationship between knowledge, university, and physical space has roots in classical antiquity. Education was structured around open spaces such as the gymnasium and the agora, which were essential in Greek paideia, where the pursuit of truth was linked to the urban environment. Institutions such as Plato’s Academy and Aristotle’s Lyceum laid the foundations for an educational model centered on intellectual communities rather than specific buildings.

In the Middle Ages, universities consolidated dedicated architectural structures, such as cloisters, which functioned as ideal spaces for knowledge transfer (Campos, 2000). Medieval monasteries, with their commitment to isolation, represented “small microcosms or ideal cities” (Campos, 2000, p. 210) that influenced later generations of universities.

The urban expansion of the 13th century gave rise to the need for constructing specific and functional spaces for universities, such as Merton College (1262) in Oxford, New College (1380-1404) in Britain, and the College of Navarre (1304) in Paris. These designs incorporated courtyards, chapels, and shared rooms, adapting both to academic and representative needs (Serra Desfilis, 2013). Alfonso X of Castile, in Las Siete Partidas (SevenPart Code; 1256-1265), emphasized the importance of functional buildings removed from urban noise for Estudios Generales, a principle later applied by Cardinal Cisneros at the University of Alcalá de Henares.

In England, the Oxford and Cambridge model, with their large multifunctional halls, introduced a monastic-residential style that influenced modern campus design. In America, the University of Virginia (1817), designed by Thomas Jefferson, reimagined this tradition with a romantic connection between architecture and nature, integrating academic buildings with landscaped spaces (Bonet, 2014). This approach solidified, in the 18th and 19th centuries, the concept of the university campus as an autonomous, planned space, where institutions like Harvard and Yale became global benchmarks. Their design fostered both intellectual interaction and a sense of community, combining ideals of progress and coexistence.

The German model promoted by Wilhelm von Humboldt in the early 19th century marked a new phase in university architecture. Humboldt prioritized the integration of research and teaching, promoting functional designs that merged with the cultural and urban fabric of cities. This approach diverged from the autonomous American campus, opting instead for structures that engaged with their social environment (Wilson, 2014).

The educational reforms driven by Napoleon Bonaparte in the same century centralized State control over universities and redefined their academic and architectural functions (Piskunova, 2020). This period consolidated buildings oriented toward scientific research and the operational demands of modernity (Campos, 2000).

In summary, the evolution of university architecture, from the open spaces of classical antiquity to the planned campuses of the 19th and 20th centuries, not only responds to functional needs but also projects cultural values and visions. These physical spaces narrate institutional history and engage with the present and future, becoming fundamental pillars for the construction of corporate and heritage identity.

3. Hypothesis and Objectives

The general hypothesis guiding our research is that architecture, as a symbol of institutional heritage, plays a predominant role in the audiovisual narrative of universities, reinforcing their corporate identity and positioning them as heritage brands.

We propose two research questions (RQ) that will guide our study:

4. Methodology

To address our hypothesis and RQs, we draw on the institutional communication promoted by universities as a reference. According to Rodrich Portugal (2012), institutional communication strategically coordinates an organization’s internal and external communications to build and maintain a favorable reputation among key audiences. In this process, image formation is essential, as it combines factors such as the institution’s history, intentional and unintentional communication, media and opinion leader narratives, and individual and social perceptions of its audiences (Capriotti, 1999). Costa (1977) complements this perspective by stating that an organization’s image in the receiver’s mind is shaped as an accumulation of perceptions, influenced by the institution’s direct actions and by its messages conveyed through various channels. Within this framework, institutional videos serve as a key tool that, through audiovisual language, not only informs but also promotes the institution’s image, strengthening its identity in comparison to competitors, suppliers, and stakeholders (Alzate et al., 2002).

For the analysis of university institutional videos, adopting an exclusively quantitative approach is insufficient, given that this audiovisual genre presents diverse formal styles and constructs narratives designed to reflect specific identity values (Milán Fitera, 2017). Therefore, the methodology employed was qualitative, with an emphasis on discourse analysis. This approach enables the interpretation of narrative and symbolic elements in videos concerning their institutional, social, and cultural contexts. Flexible viewing sheets, integrating thematic dimensions based on the HQ model, were used. This holistic methodology, aligned with Milán Fitera’s (2017) recommendations, aims at a comprehensive interpretation of the videos.

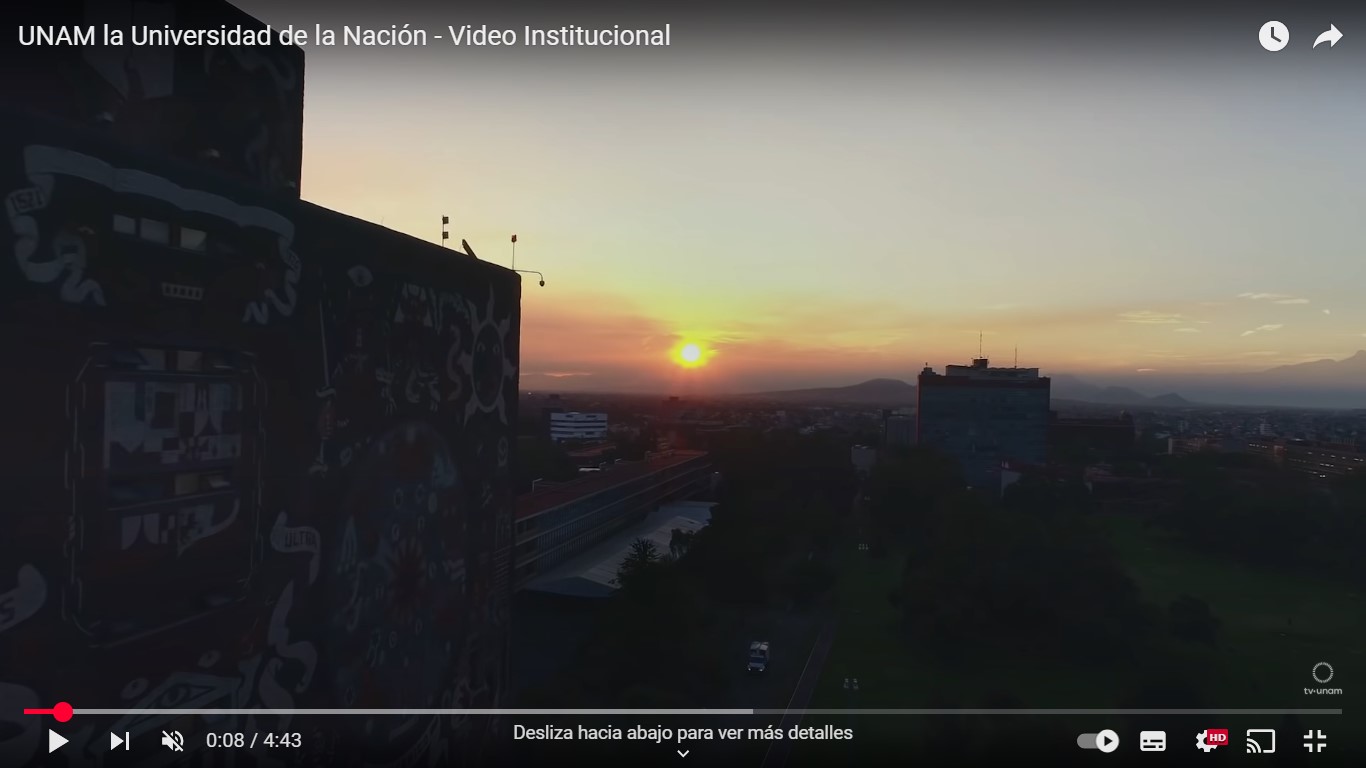

The sample (Table 1) was defined by selecting universities whose main buildings are listed as “UNESCO World Heritage Sites” (UNESCO World Heritage Centre, n.d.), and considered those that have official institutional videos available online. The inclusion criterion for the videos was their status as the main institutional video currently presented or promoted by the university through its official channels. This ensures the analysis is based on materials that are formally representative of each university’s public image.

The study includes the University of Alcalá, the University of Coimbra, and the National Autonomous University of Mexico. These universities share a common criterion: they meet UNESCO’s Criterion II (exhibit an important interchange of human values, over a span of time or within a cultural area of the world, on development in architecture or thechnology, monumental arts, town-planning or landscape design) and Criterion IV (be an outstanding example of a type of building, architectural or technological ensemble or landscape which illustrates significant stages in human history) for inclusion in the world heritage list. The Astronomical Observatory of Kazan Federal University was excluded from the analysis, as this building does not represent the institution’s core identity.

To structure the analysis, the HQ model proposed by Urde et al. (2007) was employed with modifications tailored to the analysis of institutional videos. The HQ model includes - as a reminder - five main dimensions: trajectory (representation of historical achievements and institutional milestones); longevity (references to the institution’s time of existence); values (explicit statements of principles, mission, and vision); symbols (visual or discursive references to representative elements such as buildings, logos, or emblems); and history (use of historical references as part of the institutional narrative).

5. Results

5.1. University of Coimbra

Founded in 1290, the University of Coimbra is one of the oldest academic institutions in Europe. Its main building, Palace of Schools, was originally a royal palace built in the 10th century and converted into a university headquarters in the 16th century. The predominant architectural style is Manueline, with influences from renaissance and baroque styles (Dias, 1988), highlighted by the emblematic University Tower, a symbol of the institution. During the 18th century, under the reign of King João V, the Joanina Library was built, a masterpiece of Portuguese baroque architecture. The university was designated a “UNESCO World Heritage Site” in 2013 (Universidade de Coimbra, n.d.).

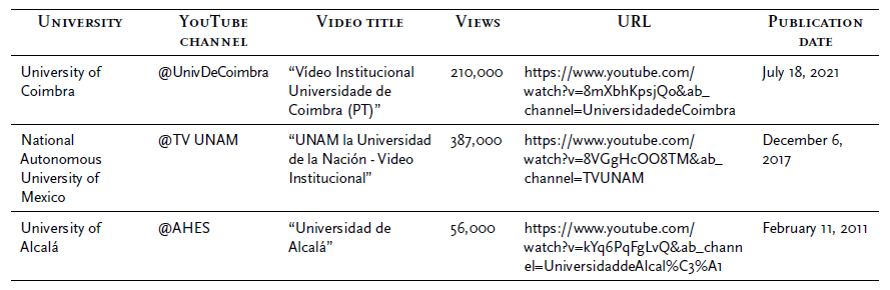

The institutional video of the University of Coimbra constructs a narrative that combines history, values, and architectural symbols to highlight its relevance as one of the oldest universities in the world. From the outset, the narrator emphasizes its longevity: “we were born more than 730 years ago from the idea of a king who was also a poet and wanted to share his passion for knowledge” (00:00:27-00:00:38). This statement, accompanied by an aerial view of Coimbra’s historic center, connects the university’s foundation with a long-term cultural and academic vision, underscoring its historical role in promoting knowledge. In the video, a student walks toward the statue of King Dinis, the university’s founder and a key figure in its institutional legacy (Figure 1).

Source. From “Vídeo Institucional Universidade de Coimbra” [Video], by Universidade de Coimbra (@ UnivDeCoimbra), 2021, 00:00:27, YouTube. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8mXbhKpsjQo)

Figure 1 Screenshot from “Vídeo Institucional Universidade de Coimbra” by Universidade de Coimbra, 2021, YouTube

The symbolic dimension is evident in both discursive and visual references to its architectural heritage: “our initial idea was born, grew, and expanded throughout the city in top-level buildings and facilities” (0:01:01-0:01:08). This statement is enriched with shots showing both exterior views of the campus and emblematic interiors, such as the central courtyard and the library.

The connection with cultural heritage is also reflected in the historical and symbolic context of the city: “in the city of Pedro and Inês” (00:01:54-0:01:56). This brief but significant reference evokes the tragic love story of Pedro I of Portugal and Inês de Castro, one of the most iconic narratives in Portuguese literature and tradition. In this context, the video integrates images of students playing traditional Portuguese music in the central courtyard, where architecture serves as the backdrop (Figure 2).

Source. From “Vídeo Institucional Universidade de Coimbra” [Video], by Universidade de Coimbra (@ UnivDeCoimbra), 2021, 00:01:56, YouTube. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8mXbhKpsjQo)

Figure 2 Screenshot from “Vídeo Institucional Universidade de Coimbra” by Universidade de Coimbra, 2021, YouTube

Regarding values, the discourse emphasizes innovation, diversity, and shared learning: “we help forge ideas that open horizons and build bridges” (00:00:39-00:00:43). These words, accompanied by images of students in classrooms and laboratories, project a vision of academic collaboration. The future-oriented outlook is also evident in phrases like: “with our eyes on the future, in the region and in the world” (00:01:08- 00:01:11), which alternates views of historical buildings with contemporary activities on campus. Additionally, the university’s commitment to sustainability is reinforced by the statement “permanent renewal with environmental awareness” (00:03:06-00:03:09), accompanied by scenes showcasing the integration of green spaces on campus.

The convergence of knowledge and cultures is expressed through the idea that “the convergence of ideas, knowledge, and nationalities presents unique opportunities for learning and innovation” (00:02:08-00:02:15), while the video features images of multicultural interactions and academic activities. The voice-over concludes with an aspirational message: “we will inspire, awaken, guide, and provide all the necessary tools for ideas to be born, grow, and help make the world a better place” (00:02:55-00:03:05), emphasizing the university’s global impact. At this moment, the camera returns to shots of the historic center (Figure 3), closing the narrative circle with architecture as the protagonist.

Source. From “Vídeo Institucional Universidade de Coimbra” [Video], by Universidade de Coimbra (@ UnivDeCoimbra), 2021, 00:03:18, YouTube. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8mXbhKpsjQo)

Figure 3 Screenshot from “Vídeo Institucional Universidade de Coimbra” by Universidade de Coimbra, 2021, YouTube

5.2. National Autonomous University of Mexico

The National Autonomous University of Mexico was founded in 1910. However, its main campus, University City, was built between 1949 and 1952 under the direction of Mexican architects such as Mario Pani and Enrique del Moral. The architectural style combines modernism and functionalism, featuring murals by artists like Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros, which integrate art and education. The campus is an emblematic example of 20th-century architecture in Latin America and was designated a “UNESCO World Heritage Site” in 2007. Its design reflects Mexican cultural identity and its commitment to social values (UNESCO World Heritage, n.d.).

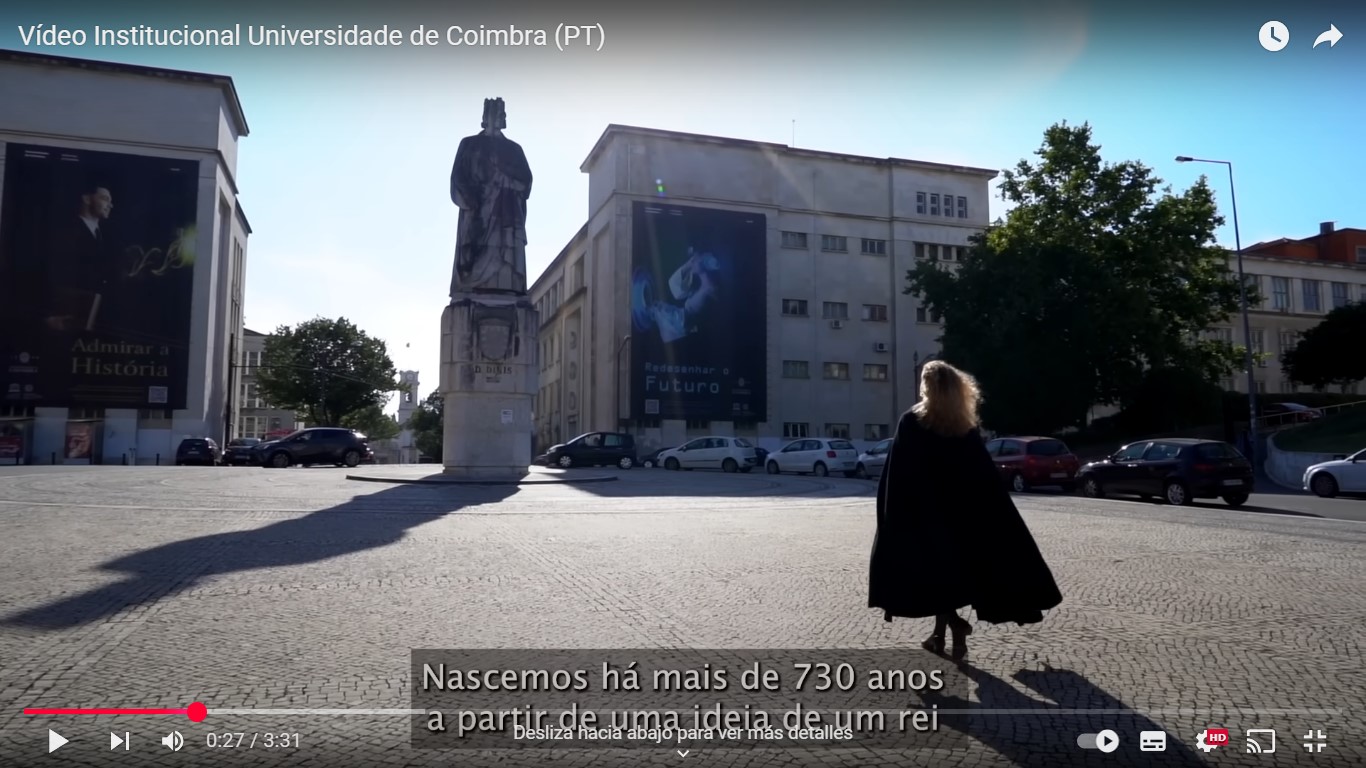

The National Autonomous University of Mexico institutional video constructs its narrative around the combination of history, values, and achievements, positioning the university as an educational and cultural benchmark in Mexico and worldwide. From the very first minutes, the voice-over emphasizes its historical relevance with statements such as: “we are a fundamental educational project in history, in the present, and for the future of Mexico” (00:00:32-00:00:37). This statement highlights its significant role in the country’s development, linking a vision of continuity between past, present, and future.

This historical narrative is visually reinforced through aerial shots emphasizing the iconic central campus. In particular, the Central Library, adorned with murals by Juan O’Gorman (Figure 4), serves as a powerful visual symbol that evokes the institution’s historical and cultural richness.

Source. From “UNAM la Universidad de la Nación - Video Institucional” [Video], by TV UNAM (@ tvunam), 2017, 00:03:15, YouTube. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8VGgHcOO8TM)

Figure 4 Screenshot from “UNAM la Universidad de la Nación - Video Institucional” by TV UNAM, 2017, YouTube

The National Autonomous University of Mexico’s trajectory is also emphasized through notable milestones: “in 2009, we were honored with the Prince of Asturias Award, and the three Nobel Prize winners that Mexico has given to the world passed through our classrooms” (00:01:54-00:02:08). These statements are reinforced by footage of the central administration building, where David Alfaro Siqueiros’ mural, “el pueblo a la universidad, la universidad al pueblo” (the people to the university, the university to the people), not only adorns its façade but also symbolizes the dynamic relationship between the university and Mexican society. Close-up shots of the university’s coat of arms on the main building further strengthen its institutional identity.

Regarding institutional values, the video explicitly conveys a commitment to diversity, inclusion, and pluralism: “we are a public university and are open to the world regardless of religious beliefs, race, sexual orientation, gender, political ideology, or economic status” (00:02:55-00:03:05). This message reinforced with shots of the sculpture garden, featuring works by Helen Escobedo, Mathias Goeritz, and Manuel Felguérez, reflects a creative environment that fosters innovation. The voice-over further emphasizes these values with phrases such as: “we are driven by the desire to learn and share in an environment of diversity, respect, and unity” (00:01:18-00:01:25), while the iconic steps of the Central Library serve as the backdrop for a dance performance, symbolizing the university’s vibrant cultural life (Figure 5).

Source. From “UNAM la Universidad de la Nación - Video Institucional” [Video], by TV UNAM (@ tvunam), 2017, 00:01:06, YouTube. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8VGgHcOO8TM)

Figure 5 Screenshot from “UNAM la Universidad de la Nación - Video Institucional” by TV UNAM, 2017, YouTube

The longevity of the National Autonomous University of Mexico is addressed by highlighting its impact on the lives of millions of Mexicans: “we are the best-designed mechanism of social capillarity and are part of the biography of millions of Mexicans” (00:03:05-00:03:11).

Finally, the symbolic dimension plays a leading role in the video. The central campus is presented not only as an educational space but also as a place of connection between tradition and modernity: “our central campus is a World Cultural Heritage site, and we have buildings of immense historical value” (00:03:12-00:03:23). The Central Library, with its monumental façade, and the Rectory building are recurring features in the footage (Figure 6), emphasizing architecture’s role as a vehicle that communicates the institution’s identity and values.

Source. From “UNAM la Universidad de la Nación - Video Institucional” [Video], by TV UNAM (@tvunam), 2017, 00:00:08, YouTube. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8VGgHcOO8TM)

Figure 6 Screenshot from “UNAM la Universidad de la Nación - Video Institucional” by TV UNAM, 2017, YouTube

5.3. University of Alcalá

The University of Alcalá was founded in 1499 by Cardinal Cisneros to reform higher education in Spain. Its main building, San Ildefonso College, is a masterpiece of Spanish renaissance architecture, designed by architects such as Pedro Gumiel and Rodrigo Gil de Hontañón. The richly decorated plateresque façade is one of the most outstanding examples of this style in Spain. The university played a crucial role in the dissemination of humanism and was the site where the first edition of the Complutensian Polyglot Bible was printed. Designated a “UNESCO World Heritage Site” in 1998, its architecture and intellectual legacy make it a symbol of the Spanish renaissance (Rivera, 2016).

The institutional video of the University of Alcalá employs a classic audiovisual narrative that reinforces its identity as a historic and prestigious institution. From the very first seconds, its foundation in 1499 by Cardinal Cisneros is highlighted: “the University of Alcalá was founded by Cardinal Cisneros in the year 1499. Some of the greatest names in Spanish culture, such as Lope de Vega, Francisco de Quevedo, and Tirso de Molina, have passed through its halls” (00:00:02-00:00:17). This statement is complemented visually by a majestic aerial view of the main building (Figure 7), the San Ildefonso College, which opens and closes the video, emphasizing its historical and architectural significance.

Source. From “Universidad de Alcalá” [Video], by Universidad de Alcalá (@uahes), 2011, 00:00:09, YouTube. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kYq6PqFgLvQ)

Figure 7 Screenshot from “Universidad de Alcalá” by Universidad de Alcalá, 2011, YouTube

The historical dimension is expanded with references to the city’s cultural context: “the city where Cervantes was born is infused with university activity, providing an exceptional setting for academic life and numerous meeting spaces for culture, the arts, and knowledge” (00:00:28-00:00:40). This segment accompanied by shots of the historic centre’s streets, including a close-up of the statue of Don Quixote, evokes the figure of Cervantes as a cultural symbol of the university’s surroundings (Figure 8).

Source. From “Universidad de Alcalá” [Video], by Universidad de Alcalá (@uahes), 2011, 00:00:28, YouTube. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kYq6PqFgLvQ)

Figure 8 Screenshot from “Universidad de Alcalá” by Universidad de Alcalá, 2011, YouTube

The video also highlights the Paraninfo as an emblematic space: “the University Auditorium witnesses the annual presentation of the most important award in Spanish literature, the Cervantes Prize, as well as the King of Spain Human Rights Award” (00:01:14-00:01:26). In this case, the camera pans across space, highlighting its architectural richness and its significance as the setting for culturally and institutionally significant events.

Regarding values, the video reinforces its commitment to academic excellence and internationalization: “the University of Alcalá promotes high-quality research in all fields of knowledge” (00:02:23-00:02:28), as well as its student-centered approach: “the priority of the University of Alcalá is its students” (00:03:43-00:03:46). These messages are combined with shots showing a historic building repurposed as a fine arts workshop. Additionally, the video concludes with a synthesis of its values: “today, the University of Alcalá is a symbol of tradition and progress, of humanism and science, of growth and sustainability” (00:04:25-00:04:37).

The symbolic dimension assumes special prominence, incorporating visual elements that connect the university to its medieval tradition. For example, a close-up shot shows the sign of Porta Coeli guesthouse, designed with the Vitor typeface, a resource that evokes the university’s medieval heritage and underscores the link between past and present. This deliberate use of symbolism reinforces the narrative of historical continuity and institutional prestige.

Finally, in terms of trajectory, the video highlights its global recognition: “in 1998, the University and the historic center of the city of Alcalá de Henares were declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site” (00:00:17-00:00:26). This mention, accompanied by a panning shot of the main façade of the San Ildefonso College (Figure 9), reinforces its positioning as an academic and cultural reference.

Source. From “Universidad de Alcalá” [Video], by Universidad de Alcalá (@uahes), 2011, 00:00:50, YouTube. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kYq6PqFgLvQ)

Figure 9 Screenshot from “Universidad de Alcalá” by Universidad de Alcalá, 2011, YouTube

Overall, the University of Alcalá constructs a narrative that integrates history, architectural symbols, and values to project a strong identity intricately linked to its heritage legacy. Visual references to architecture and the city’s cultural elements complement the verbal discourse, reinforcing the perception of the university as an institution that harmonizes tradition and modernity.

6. Conclusions

This research illustrates that architecture plays a central and multifaceted role in shaping the corporate identity of heritage universities. Through the qualitative discourse analysis of institutional videos from the University of Coimbra, the National Autonomous University of Mexico, and the University of Alcalá, it is demonstated that architecture functions not only as a physical space but, more importantly, as a key symbolic element in institutional communication. This symbolism serves to reinforce each institution’s legitimacy, continuity, and prestige, thus anchoring their corporate identity within a broader heritage framework.

In direct response to the first RQ, the study found that all five dimensions of the HQ model - trajectory, longevity, core values, symbols, and history as identity - are clearly represented across the analyzed videos. Nevertheless, the symbolic dimension, especially architecture, stands out as the most recurrent and visually dominant element. The emblematic buildings of each university act as narrative anchors, visually and discursively legitimizing their cultural and academic heritage. This aligns with Capriotti’s (1999) and Costa’s (1977) views on institutional image as a constructed accumulation of perceptions shaped by intentional communication and symbolic references.

Regarding the second RQ, results reveal that architecture goes beyond conveying historical narratives; it strategically embodies and projects institutional values. Coimbra’s Palace of School and Joanina Library symbolize a legacy of academic excellence and multicultural openness. The National Autonomous University of Mexico’s University City and its iconic murals convey an identity deeply rooted in modernism, public education, and social commitment. Meanwhile, the University of Alcalá leverages the renaissance grandeur of the San Ildefonso College to position itself as a bastion of humanism and Spanish university tradition. These findings reinforce Rodrich Portugal’s (2012) assertion that institutional communication integrates various dimensions - history, symbolism, values - to build and maintain a favorable reputation.

Ultimately, this study shows that architectural heritage is not merely an aesthetic or historical feature; rather, it is a strategic asset and branding tool that significantly enhances the differentiation and positioning of heritage universities in a competitive global context. By integrating architecture prominently in their audiovisual narratives, these universities consolidate a corporate image that bridges tradition and innovation, appealing simultaneously to internal and external stakeholders. This dual role of architecture - both as tangible heritage and as a symbol imbued with meaning - affirms its pivotal function in institutional identity construction and heritage brand management.

This study focuses on the communicative intention of universities in constructing their institutional image, without addressing how these messages are received or interpreted by their audiences. Future research could therefore explore reception, analyzing how architectural heritage and symbolic elements are perceived by different stakeholders. It would also be relevant to expand the corpus beyond official institutional videos, incorporating other audiovisual and communicative formats - such as content disseminated on social media - which today play an increasingly prominent role in shaping institutional identity. Moreover, the analytical model applied here could be extended to other institutional brands whose identity is firmly anchored in their physical environment.

texto em

texto em