Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Media & Jornalismo

versão impressa ISSN 1645-5681versão On-line ISSN 2183-5462

Media & Jornalismo vol.19 no.34 Lisboa jun. 2019

https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-5462_34_14

ARTIGO

Personal traits behind the intention to Donate Blood

Traços pessoais por detrás da intenção de Doar Sangue

Ana Margarida Barreto*

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7465-327X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7465-327X

*Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas. Instituto de Comunicação da NOVA

ABSTRACT

Understanding the impact of personal traits on prosocial behavior becomes vital for the development of effective advertising messages to the target audience. Hence, this exploratory study was developed to contribute to a better understanding of the motivations of actual and potential blood donors, by analyzing and comparing the effect of some of the most prominent personal traits for predicting or explaining prosocial behavior (blood donation).

125 participants from generation Y answered an online survey that besides asking about their blood donation intention also pertained to establish a relation with their personality traits by considering: attribution theory, self-image, social responsibility, altruism, social influence, and empathy. We also take into consideration the possible effect of framing.

According to our findings, blood donors are positively influenced to donate blood by self-image and internal attribution. On the other hand, nondonors are only positively influenced by self-image.

Keywords: blood donation; prosocial behavior; motivators

RESUMO

A compreensão do impacto dos traços pessoais no comportamento pró-social torna-se vital para o desenvolvimento de mensagens publicitárias eficazes junto do público-alvo. Este estudo exploratório foi por isso desenvolvido com o fim de contribuir para uma melhor compreensão sobre as motivações dos dadores de sangue actuais e potenciais, analisando e comparando o efeito de algumas das características pessoais mais proeminentes na previsão ou explicação do comportamento pró-social (doar sangue).

125 participantes da geração Y responderam a um inquérito on-line que, além de questionar sobre a sua intenção de doar sangue também estabelecia uma relação com os seus traços de personalidade considerando: teoria da atribuição, auto-imagem, responsabilidade social, altruísmo, influência social e empatia. Também foi tida em consideração o possível efeito do enquadramento da mensagem.

De acordo com os nossos resultados, os dadores de sangue são influenciados positivamente pela auto-imagem e pela atribuição interna. Por outro lado, os não dadores de sangue são positivamente influenciados apenas pela auto-imagem.

Palavras-chave: doação de sangue; comportamento pró-social; motivações

Introduction

Despite an increase of reported blood donations in recent years, a severe shortage of donated blood remains a critical issue (World Health Organization, June 2017). In many countries more than 50% of blood supply is collected from family/replacement or paid donors, which is why recently the World Health Organization, the International Federation of Red Cross and the Red Crescent Societies have set the ambitious aim to achieve 100% voluntary blood donation.

Particular consideration is necessary to increase the percentage of voluntary, or un-paid, donations, as currently only represents 30% of the global blood supply. This is a key issue because for every donation of blood three lives can be saved[1]. Understanding motivations is central to understanding, and consequently influencing, voluntary behavior change (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Accordingly, the purpose of this paper is to further elucidate the internal motivations for donating blood as a means to developing more effective campaigns. We particularly focus our research on students. Previous research identified younger donors, chiefly donors pertaining to “Gen Y”, as a particularly difficult segment who are difficult to acquire and exhibit low retention rates (Russell-Bennett, Hartel, Russell, & Previte, 2012). It is therefore appropriate to focus specifically on this segment.

Increasing Blood Donations as an Issue in Social Marketing

While an important topic for health professionals, blood donation has been a relatively minor topic in social marketing, with only a small number of papers examining ways of increasing the behavior from a social marketing perspective (Truong, 2014). Of these, Polonsky et al (2015) examined blood donation from migrant populations, a analogously hard to reach and motivate population as Gen Y. Their findings highlighted the importance of removing barriers as a “hygiene factor” for increasing blood donations, though noted that this alone is not sufficient to motivate people to donate. Previously, Russel-Bennet et. al. (2013) suggested improvements in service quality as a means to increase blood donations, while Beerli-Palacio and Martín-Santana (2009) suggested that providing information is key to increase the disposition to donate blood. Kidwell and Jewell (2003) studied blood donation amongst university students as an example of the applicability of the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB), and highlighted internal control factors as the most likely to influence behaviour. Contradicting the importance of TPB, Holdershaw et al (2011) find that TPB is a poor predictor of actual behaviour. The gap between intention and actual behaviour has also been highlighted by Griffin et al. (2014), with a call for more research focusing on motivational factors. However, it should be noted that previous experience with blood donations has been consistently noted to be a contributor to future blood donations by the aforementioned studies.

Apart from internal factors, external rewards, have also been studied. In their Cochrane review, Mortimer et al. (2013) find that, although public financial incentives (PFI) show a positive impact on blood donations, such impact on future donations is negative where PFIs are withdrawn.

Few studies have analyzed blood donation from the social marketing and social promotion/advertising perspective so far. One recent exception is the work of Healy & Murphy’s (2017) on social marketing advertising messages to increase the supply of blood among young donors and non-donors. The authors found that young people found most effective advertising messages that stressed the altruistic nature of donating blood. While to non-donors the advertisements that could be more effective were the rational-based fear advertisements that challenged their excuses and complacency to donate. On the other hand, Ferguson and Lawrence (2016) found that blood donation is not pure altruism (caring about the welfare of others at personal expense) but rather a mixture of warm-glow giving (finding the act of donation emotionally rewarding) and reluctant altruism (cooperation in the face of free-riding rather than punishment of free-riders). For Kolins & Herron (2003) the way to achieve growth in blood donor numbers lies with a market-type approach with targeted marketing campaigns aiming young people.

Hence, the contribution this paper makes is therefore two-fold: Firstly, by focusing on the personality traits as a guide to developing promotional material, we further contribute to the literature on the subject of blood donations. Secondly, by researching motivations of Gen Y blood donors, we contribute to an understanding of this hard to reach, and hard to motivate target group, which seems to be more prompt to express their individuality through practices that resemble sharing rather than giving (Urbain et al., 2013).

Establishing the Personality Traits

As the aim of this paper is to understand the effect of some personality traits on blood donation intention of Gen Y blood donors, we decided to test six potential motivating factors (empathy, altruism, social responsibility, social influence, self-image, attribution) with a view to providing social marketers with assistance in order to develop potentially successful social marketing campaigns, and more specifically promotional campaigns designed to encourage Gen Y blood donors.

Empathy, or the “affective response that stems from the apprehension or comprehension of another’s emotional state or condition, (…) similar to what the other person is feeling or would be expected to feel” (Eisenberg, 2010, p.1) has been discussed as a possible factor influencing prosocial behavior (Einolf, 2008), but very few studies have tried to understand if and how it impacts blood donation behavior or donation intention. One example is Karacan et al (2013) study that showed that empathic concern had no effect as a predictor for blood donation motivation.

Within the blood donation literature, altruism has been traditionally highlighted as not having a strong effect on blood donation (c.f. Evans & Ferguson, 2014). However, this finding is not consensual, since it contradicts a recent study that highlighted that altruism is the biggest reason why young people donate blood (Healy & Murphy, 2017).

Social responsibility, or “feelings of moral obligation to act pro-socially” (De Groot & Steg, 2009, p. 443), have also been associated with increasing intentions to perform a range of prosocial behaviors, including blood donations (Ibid.). However, as it happens with empathy, there is still no sufficient empirical evidences in the literature on the impact of social responsibility on blood donation behavior. In fact, while this motivator has traditionally been linked with prosocial behaviors, Griffin, Grace and O'Cass (2014) study actually points out that individuals may be socially responsible, may find the blood donation issue important, may evaluate the issue positively, and yet, be non-donors.

According to Sojka and Sojka (2008) study, social influence has been one of the most frequently reported reasons for giving blood the first time (47.2% of donors were influenced by a friend), while the most commonly reported motive for donating blood (among general reasons/motives with highest ranking of importance) were general altruism’ (40.3%), social responsibility/obligation’ (19.7%) and influence from friends’ (17.9%). These findings are in line with the ones from Griffin, Grace and O'Cass (2014). Focused on comparing individual characteristics, attitudes, and feelings of blood donors and nondonors, the authors found that the relationship between susceptibility to interpersonal influence and attitude towards the issue was significant only for donors, but it was a negative relationship, supporting the view that donors are less likely to be influenced by social pressure.

Self-image, or the totality of internalized images and ideas a person holds about themselves, also plays an important part when guiding behavior, a relationship that has a longstanding tradition within the marketing literature and is considered fundamental when designing persuasive marketing strategies (Sirgy, 1982). For example, people who consider themselves as moral consumers, tend to look for and respond more favorably to marketing strategies emphasizing principles aligned to their values.

According to attribution theory, the perception that a person may have about who asks for help can be crucial in deciding whether to assist or not. This theory explains that in this situations people make a kind of judgment, the "attribution", internal (ability, effort) or external (task difficulty, luck), on the behavior of others or themselves, attributing causes to events. Attributions can be directed to the fact that a person is in need or can be made on the character of the person who helps (Heider, 1958, and Jones and Davis, 1965, cited by Batson and Powell, 2003). For instance, in Decety et al. (2010) study participants were significantly more sensitive to the pain of individuals who had contracted AIDS as the result of a blood transfusion as compared to individuals who had contracted AIDS as the result of their drug addiction. In Conner et al. (2013) study perceived behavioral control, combined with anticipated negative affective reactions, cognitive attitude, anticipated positive affective reactions and subjective norms, was found to be a significant predictor of intentions to donate blood. In short, the perception that the benefactor has about the person or institution asking for help can sometimes be decisive in the decision to help or not.

Methodology

In order to better understand the motivational factors that should be used to guide social marketing, especially social advertising campaigns a survey was developed and administered to 125 undergraduate students at a Portuguese university.

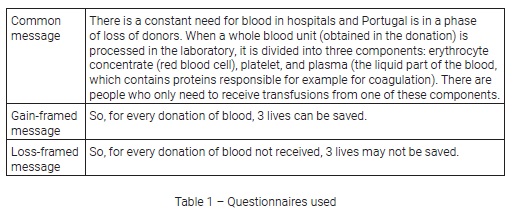

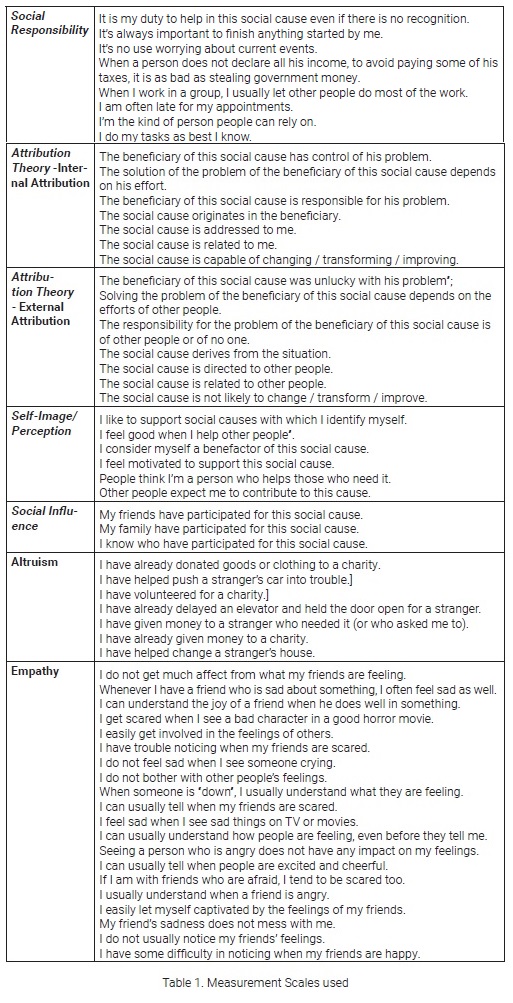

The survey started with a brief introductory text about blood donations. In order to avoid framing effects, the text concluded with either a gain-framed or loss-framed message (see Table 1). Respondents were randomly assigned to see either a loss- or a gain-framed conclusion message (gain-frame: 70 students; loss-frame: 55 students).

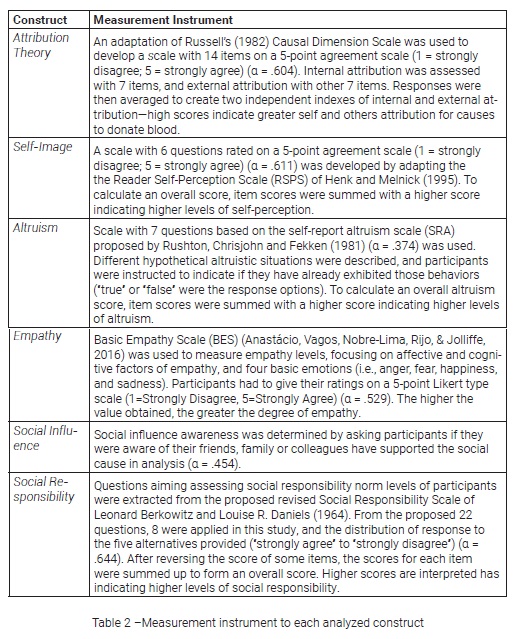

Following on from this, the respondents were asked about their blood donation intention and if they had previously given blood. This was followed by questions designed to measure their motivational factors in a randomized order (see attachment). The questions used for this were based on the sources given in Table 2. All questions used can be found on Table 1 in Attachments.

Results

4. Results:

Of all participants, 88.8 per cent expressed a donation intention, despite the fact that the majority have not donated blood before (72 per cent). Moreover, the majority of both groups exposed to a gain-framed message (87 per cent) and to a loss-framed message (91 per cent) agreed on donating blood. Not surprisingly, the ANOVA showed no significant main effect of the gain-and loss-framed messages on the intention scores (p = .511).

In order to evaluate the possible impact of personality traits with respect to each the already mentioned theories on blood donation intention two binominal logistic regression model were employed (for current donors and non-donors) that included blood donation intention as dependent variable, social influence index, self-concept score, social responsibility score, internal and external attribution scores, and empathy and altruism scores as predictors (independent variables).

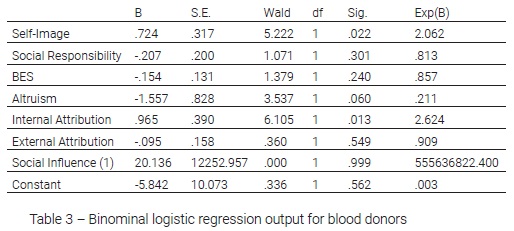

For current donors, the explained variation in the dependent variable based on this binominal logistic regression model ranges from 36.7% to 68.5% (Cox & Snell R2 and Nagelkerke R2 methods, respectively). The Hosmer & Lemeshow test of the goodness of fit suggests the model is a good fit to the data, that is, the estimated values are close to the values observed, so the model fits the data with a Chi- square value of 1.420 (8) and p=0.994 (>.05).

Our data suggest that for current blood donor’s self-image (b = .725, p = .022) and internal attribution (b = .965, p = .013) added significantly to the model/prediction, but the remaining variables did not add. Moreover, internal attribution seems to be the variable that most significantly impact the depended variable (donation intention), positively (Table 3).

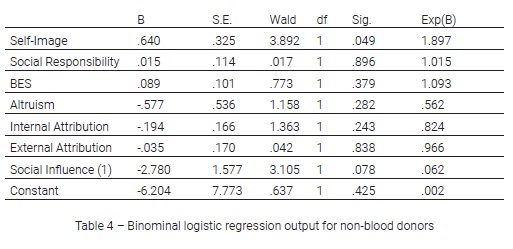

For non-donors, the explained variation in the dependent variable based on this logistic regression model ranges from 13.6% to 29.9% (Cox & Snell R2 and Nagelkerke R2 methods, respectively). The Hosmer & Lemeshow test of the goodness of fit suggests the model is a good fit to the data, that is, the estimated values are close to the values observed, so the model fits the data with a Chi- square value of 6.056 (7) and p=0.533 (>.05).

Our data suggest that for this group self-image (b = .640, p = .049) added significantly to the model/prediction, but the remaining variables did not add significantly to the model/prediction (Table 4).

5. Discussion of Results

The main purpose of this study was to contribute to a better understanding of actual and potential blood donors’ motivations by analyzing and comparing the effect of some of the most prominent personal traits for predicting or explaining intention to donate blood (attribution theory, self-image, social responsibility norm, altruism, social influence and empathy), as well as the effect of framing on the decision to be (or not) a blood donor.

According to our findings, actual blood donors are positively influenced by both internal attribution and self-image, while potential donors (who have not donated blood) seem to be (positively) influenced only by self-image.

According to the theory of self-perception, people act prosocially for the happiness they expect to feel when helping others. When people reflect on experiences of donations, they tend to see themselves as benefactors, rather than seeing themselves as beneficiaries, developing prosocial behavior, fulfilling and affirming the desire to help (Freedman and Fraser, 1966; Daryl Bem, 1972). This perception contributes to strength their values and their identities as careful, attentive, and prosocial individuals. So, by seeing themselves as benefactors, people feel happier and more motivated to help (Verplanken and Holland, 2002).

We interpret our own actions the way we interpret others’ actions, and our actions are often socially influenced and not produced out of our own free will, as we might expect (Bem, 1972). So, when we talk about self-image or self-perception it is almost impossible to neglect the role of social influence in one’s mind. Moreover, previous studies (Reid and Wood, 2008; Nook et al., 2016) have concluded that social influence has an impact on participants’ blood donation intention and that this influence could be affected by prior experience (Sojka and Sojka, 2008). Interestingly, our data suggests that social influence has no effect on donation intention.

It is worth mention that this data comes from a self-report survey. Despite the fact that answers were collected anonymously, it is plausible that our participants may wanted to show a version of themselves aligned with what society expects from them or approves. Yet, the gap between attitude and action (when what people say and what they do are different) is well known in the literature applied to social domains (see for instance Carrington et al, 2010). As Carrington et al (2010) proposes, many of us do intend to act more ethically than we end up actually doing, being hampered by various constraints and competing demands before we perform as we would like.

People tend to see cause and effect relationships. Apparently, past donors when they assign the cause of a behavior to internal characteristics, rather than to outside forces show higher blood donation intention. On the other hand, situational or environment features of the event (external attribution) seem not to affect donation intention. In other words, when the attribution of causality or causal locus is perceived as internal seems to trigger an emotional state that lead to help (Weiner, 1980).

Altruism, empathy, and social responsibility had no effect on blood donation intention. Although at first glance counter-intuitive, this observation confirms previous findings from the literature. Griffin, Grace and O'Cass (2014) concluded that individuals may be socially responsible, may find the blood donation issue important, may evaluate the issue positively, and yet, be nondonors. In addition, previous literature suggested that, in the context of blood donation, altruism is multifaceted and complex and does not reflect pure altruism (Evans and Ferguson, 2014). Previous studies have also suggested that empathic concern may not be an important motivator for planned helping decisions and decisions to help others who are not immediately present (Einolf, 2008; Forgiarini et al., 2011; Decety and Cowell, 2015; Melloni et al., 2014).

Finally, our data also suggest that message frames (gain vs. loss) had no main effect on donation intention. Again, intuitively surprising, this observation contradicts the findings from other researchers (Reinhart, Marshall, Feeley, and Tutzauer, 2007; Cao, 2016), so it should be taken consciously. Perhaps the lengthy framing rather than a small quick and easy message may have contributed to this result and little attention has been paid by participants to the second part of the message with either a gain-framed or loss-framed.

6. Conclusion and Research Agenda

Understanding personality traits is vital when developing advertising messages that resonate with the target audience. Historically, blood donation campaigns tend to appeal to altruistic motives for giving blood, such as “give the gift of blood” or “save a life, give blood”. However, for Gen Y donors, this type of motivational appeal may not be suitable, as neither existing nor potentially new donors appear to be motivated by altruism. Instead, based on these findings, future campaigns should be more focused on the self-image of the donor and less on the victim, as well on internal attribution in the case of actual donors.

Hence, following McVittie, Harris, and Tiliopoulos (2006) call for a better understanding of blood donation intentions, this paper contributes to the debate by highlighting the vital role of self-image (for both donors and non-donors) and internal attribution (donors), while at the same time opening up avenues for future research.

This study has some limitations, yet it stills contributes to the debate. The most prominent finding of the study is that self-perception /image has a stronger and positive impact on pro-social behavior (blood donation intention) than other motivators, such as social influence, social responsibility norm, altruism, social learning and empathy. As mentioned before, to our knowledge no previous study attempted to understand the relation between self-image and blood donation behavior or intention among donors and no donors. Hence, by confirming the positive relation between both variables in both conditions we believe we are promoting the need for more empirical evidences in this domain.

The dependent variable (donation intention) is dichotomous. Future studies could benefit from a continuous measure, which could deal with the ceiling effect found in this study (90% of the participants responded positively). Also, several scenarios are needed to increase the accuracy of the measurements. Hence, more studies are needed that can shed more light on the effects of social influence on the analyzed domain, as well as understanding the negative impact of altruism and social responsibility perception warrants examination. For instance, could the type of relation between the sender and the receiver determine the effectiveness of a social campaign?

It has been argued that, with repeated performance, past behavior can also be a predictor of intentions and behavior (e.g., Conner & Armitage, 1998; Conner, Warren, Close, & Sparks, 1999; Conner et al., 2002). We have asked participants if they have donated, but we did not ask them how many times.

Also, participants were primed with a particular framing, but our data suggest that message frames (gain vs. loss) had no main effect on donation intention, contradicting past observations (Reinhart, Marshall, Feeley, and Tutzauer, 2007; Cao, 2016). Hence, future research should look to how long framing effect last.

Finally, one should bear in mind the difference between intention and action, which stress the need for new studies that can confirm or reduce this attitude-action gap on blood donation.

REFERENCES

Anastácio, S., Vagos, P., Nobre-Lima, L., Rijo, D., & Jolliffe, D. (2016). The Portuguese version of the Basic Empathy Scale (BES): Dimensionality and measurement invariance in a community adolescent sample. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 13(5), 614-623. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2016.1167681 [ Links ]

Batson, C. D., & Powell, A. A. (2003). Altruism and Prosocial Behavior. In T. Millon, & J. M. Lerner, Handbook of Psychology (pp. 463-484). New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken. [ Links ]

Beerli-Palacio, A., & Martín-Santana, J. D. (2009). Model explaining the predisposition to donate blood from the social marketing perspective. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 14(3), 205-214. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.352 [ Links ]

Bem, D. J. (1972). Self-perception theory. Advances in experimental social psychology, 6, 1-62. [ Links ]

Cao, X. (2016). Framing charitable appeals: the effect of message framing and perceived susceptibility to the negative consequences of inaction on donation intention. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 21(1), 3-12. [ Links ]

Conner, M., & Armitage, C. (1998). Extending the theory of planned behavior: A review and avenues for further research. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28, 1429-1464. [ Links ]

Conner, M., Godin, G., Sheeran, P., & Germain, M. (2013). Some feelings are more important: Cognitive attitudes, affective attitudes, anticipated affect, and blood donation. Health Psychology, 32(3), 264. [ Links ]

Conner, M., Norman, P., & Bell, R. (2002). The theory of planned behaviour and healthy eating. Health Psychology, 21, 195-201. [ Links ]

Conner, M., Warren, R., Close, S., & Sparks, P. (1999). Alcohol consumption and the theory of planned behavior: An examination of the cognitive mediation of past behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29(8), 1676-1704. [ Links ]

De Groot, J. I. M., & Steg, L. (2009). Morality and Prosocial Behavior: The Role of Awareness, Responsibility, and Norms in the Norm Activation Model. The Journal of Social Psychology, 149(4), 425-449. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.149.4.425-449 [ Links ]

Decety J, Cowell JM. (2015) Empathy, justice, and moral behavior. AJOB Neuroscience. 6, 3-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/21507740.2015.1047055 [ Links ]

Decety J, Echols S, Correll J. (2010) The blame game: the effect of responsibility and social stigma on empathy for pain. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 22, 985-997. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2009.21266 [ Links ]

Einolf, C. J. (2008). Empathic concern and prosocial behaviors: A test of experimental results using survey data. Social Science Research, 37(4), 1267-1279. [ Links ]

Eisenberg, N. (2010). Empathy-related responding: Links with self-regulation, moral judgment, and moral behavior. Prosocial motives, emotions, and behavior: The better angels of our nature, 129-148.

Evans, R., & Ferguson, E. (2014). Defining and measuring blood donor altruism: a theoretical approach from biology, economics and psychology. Vox Sanguinis, 106(2), 118-126. https://doi.org/10.1111/vox.12080 [ Links ]

Ferguson, E., & Lawrence, C. (2016). Blood donation and altruism: the mechanisms of altruism approach. ISBT Science Series, 11(S1), 148-157. [ Links ]

Forgiarini, M., Gallucci, M., & Maravita, A. (2011). Racism and the empathy for pain on our skin. Frontiers in psychology, 2, 108. [ Links ]

Freedman, J. L., & Fraser, S. C. (1966). Compliance without pressure: the foot-in-the-door technique. Journal of personality and social psychology, 4(2), 195. [ Links ]

Griffin, D., Grace, D., & O’Cass, A. (2014). Blood Donation: Comparing Individual Characteristics, Attitudes, and Feelings of Donors and Nondonors. Health Marketing Quarterly, 31(3), 197-212. https://doi.org/10.1080/07359683.2014.936276

Healy, J., & Murphy, M. (2017). Social Marketing: The Lifeblood of Blood Donation?. In The Customer is NOT Always Right? Marketing Orientations in a Dynamic Business World (pp. 811-811). Springer, Cham.

Healy, J., & Murphy, M. (2017). Social Marketing: The Lifeblood of Blood Donation?. In The Customer is NOT Always Right? Marketing Orientationsin a Dynamic Business World (pp. 811-811). Springer, Cham.

Heider, F. (1958). The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations. New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

Henk, W. A., & Melnick, S. A. (1995). The Reader Self-Perception Scale (RSPS): A new tool for measuring how children feel about themselves as readers. The Reading Teacher, 48(6), 470-482. [ Links ]

Holdershaw, J., Gendall, P., & Wright, M. (2011). Predicting blood donation behaviour: further application of the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Social Marketing, 1(2), 120-132. https://doi.org/10.1108/20426761111141878 [ Links ]

Jones, E. E., & Davis, K. E. (1965). From acts to dispositions the attribution process In person perception1. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 219-266). Academic Press.

Karacan, E., Seval, G. C., Aktan, Z., Ayli, M., & Palabiyikoglu, R. (2013). Blood donors and factors impacting the blood donation decision: motives for donating blood in Turkish sample. Transfusion and Apheresis Science, 49(3), 468-473. [ Links ]

Kidwell, B., & Jewell, R. D. (2003). An examination of perceived behavioral control: Internal and external influences on intention. Psychology and Marketing, 20(7), 625-642. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.10089 [ Links ]

Kolins, J., & Herron, R. (2003). On bowling alone and donor recruitment: lessons to be learned. Transfusion, 43(11), 1634-1638. [ Links ]

Martín-Santana, J. D., Reinares-Lara, E., & Reinares-Lara, P. (2018). Using Radio Advertising to Promote Blood Donation. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 30(1), 52-73. [ Links ]

McVittie, C., Harris, L., & Tiliopoulos, N. (2006). " I intend to donate but…": Non-donors' views of blood donation in the UK. Psychology, health & medicine, 11(1), 1-6.

Melloni, M., Lopez, V., & Ibanez, A. (2014). Empathy and contextual social cognition. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 14(1), 407-425. [ Links ]

Mortimer, D., Ghijben, P., Harris, A., & Hollingsworth, B. (2013). Incentive-based and non-incentive-based interventions for increasing blood donation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010295 [ Links ]

Nook, E. C., Ong, D. C., Morelli, S. A., Mitchell, J. P., & Zaki, J. (2016). Prosocial conformity: Prosocial norms generalize across behavior and empathy. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(8), 1045-1062. [ Links ]

Polonsky, M., Francis, K., & Renzaho, A. (2015). Is removing blood donation barriers a donation facilitator?: Australian African migrants’ view. Journal of Social Marketing, 5(3), 190-205. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSOCM-08-2014-0054

Reid, M., & Wood, A. (2008). An investigation into blood donation intentions among non-donors. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 13(1), 31-43. [ Links ]

Reinhart, A. M., Marshall, H. M., Feeley, T. H., & Tutzauer, F. (2007). The persuasive effects of message framing in organ donation: The mediating role of psychological reactance. Communication Monographs, 74(2), 229-255. [ Links ]

Rushton, J. P., Chrisjohn, R. D., & Fekken, G. C. (1981). The altruistic personality and the self-report altruism scale. Personality and individual differences, 2(4), 293-302. [ Links ]

Russell-Bennett, R., Hartel, C., Russell, K., & Previte, J. (2012). It’s all about me! Emotional ambivalence Gen-Y blood-donors (pp. 43-43). Presented at the Proceedings from the AMA SERVSIG International Service Research Conference, Hanken School of Economics.

Russell-Bennett, R., Wood, M., & Previte, J. (2013). Fresh ideas: services thinking for social marketing. Journal of Social Marketing, 3(3), 223-238. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSOCM-02-2013-0017 [ Links ]

Russell, D. (1982). The Causal Dimension Scale: A measure of how individuals perceive causes. Journal of Personality and social Psychology, 42(6), 1137. [ Links ]

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68. [ Links ]

Sirgy, M. J. (1982). Self-Image/Product-Image Congruity and Advertising Strategy. In V. Kothari (Ed.), Proceedings of the 1982 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual Conference (2015th ed., pp. 129-133). Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16946-0_31 [ Links ]

Sojka, B. N., & Sojka, P. (2008). The blood donation experience: self-reported motives and obstacles for donating blood. Vox sanguinis, 94(1), 56-63. [ Links ]

Truong, V. D. (2014). Social Marketing: A Systematic Review of Research 1998-2012. Social Marketing Quarterly, 20(1), 15-34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524500413517666 [ Links ]

Urbain, C., Gonzalez, C., & Gall-Ely, M. L. (2013). What does the future hold for giving? An approach using the social representations of Generation Y. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 18(3), 159-171. [ Links ]

Verplanken, B., & Holland, R. W. (2002). Motivated Decision Making: Effects of Activation and Self-Centrality of Values on Choices and Behaviour. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 443-447. [ Links ]

Weiner, B. (1980). A Cognitive (Attribution)- Emotion- Action Moel of Motivated Behavior: An Analysis of Judgments of Help-giving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2 (39), pp. 186-200.

World Health Organisation. 2010. Towards 100% voluntary blood donation - A global framework for action. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/bloodsafety/publications/9789241599696_eng.pdf?ua=1 . [ Links ]

World Health Organisation. 2017. Blood safety and availability. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blood-safety-and-availability . [ Links ]

Recebido | Received | Recebido: 2018.08.15

Aceite | Accepted | Aceptación: 2018.01.10

Notas

[1] When a whole blood unit (obtained in the donation) is processed in the laboratory, it is divided into three components: erythrocyte concentrate (red blood cell), platelet, and plasma (the liquid part of the blood, which contains proteins responsible for example for coagulation). Some people only need to receive transfusions from one of these components.

Biographical note

Ana Margarida Barreto holds a PhD degree from New University of Lisbon where she teaches Marketing, Consumer Behavior, and Strategic Communication. She completed a post-doc at Tel Aviv University where she studied attention, perception and memory, and fieldwork as a visiting scholar at University of Texas at Austin, University of Westminster, King’s College of London, and Columbia University. She is also part of the coordination team of ICNOVA and is the founder and coordinator of the research group on Strategic Communication and Decision-Making Processes of that center. Her work has been recognized with many invitations to take part in the review panel of worldwide journals, such as Communications: The European Journal of Communication Research, European Journal of Marketing, Journal of Business Research, Cogent Social Sciences, Information Processing & Management, etc, having received twice in three years the Outstanding Reviewer Award at the Emerald Literati Network Awards for Excellence (2015 and 2017). Ana Margarida Barreto has also worked for five years in communication and advertising, both in Portugal and in Spain.

Email: ambarreto@fcsh.unl.pt

Address:: Instituto de Comunicação da NOVA, Av. de Berna, 26-C - Lisboa 069-061, Portugal