Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Media & Jornalismo

versão impressa ISSN 1645-5681versão On-line ISSN 2183-5462

Media & Jornalismo vol.20 no.36 Lisboa jun. 2020

ARTIGO

The shape of crowdfunding calls for Journalism: a content analysis on Kickstarter (2010-2018)

Qual é a configuração dos projetos de crowdfunding em Jornalismo? Uma análise de conteúdo de projetos no Kickstarter (2010-2018)

¿Cuál es la configuración de los proyectos de crowdfunding en Jornalismo? Un análisis de contenido de proyectos en Kickstarter (2010-2018)

Carolina Dalla Chiesa*,

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0452-6045

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0452-6045

Mariana Scalabrin Müller**

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3993-384X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3993-384X

*Erasmus University Rotterdam (ESHCC/EUR)

**Communication and Society Research Centre (CECS)

ABSTRACT

The media landscape has drastically changed during the past decade with the emergence of new models and platforms allowing citizens to become amateur journalists and news publishers. Alongside traditional players, newcomers and do-it-yourself initiatives emerged in this market with the help of platforms that seek to engage with a potential audience and offer alternative funding means, such as crowdfunding. Success cases and innovative examples abound in the literature, often on a case-based analysis, showing the potential this funding model has to support local projects and investigative journalism. It is the aim of this paper to descriptively unveil the characteristics of such calls via a content analysis using the Kickstarter website, as this typically represents the reward-based crowdfunding model. This study contributes to discuss not only the features of calls but, furthermore, to which extent crowdfunding seems to emerge novel ways of creating and sharing media content.

Keywords: crowdfunding; journalism; content analysis; kickstarter

RESUMO

O ambiente dos media transformou-se radicalmente durante a década passada com a emergência de novos modelos e plataformas que permite aos cidadãos tornarem-se jornalistas. Juntamente das corporações tradicionais de media, novos entrantes e iniciativas “do-it-yourself” emergem no mercado com a ajuda de plataformas que buscam conectar uma demanda em potencial e oferecer alternativas de financiamento, como crowdfunding (ou financiamento coletivo). Casos de sucesso e exemplos inovadores abundam na literatura, maioritariamente apresentada com base em estudos de caso, os quais mostram o potencial deste modo de financiamento para o auxílio a projetos locais e investigativos. É objetivo deste artigo mostrar descritivamente as características desses projetos por meio de uma análise de conteúdo que usa como base a plataforma Kickstarter, um caso em geral representativo dos projetos de crowdfunding. Este estudo contribui não apenas para a discussão das características do jornalismo nos financiamentos coletivos, mas também para a crítica sobre se este meio traz contribuições para novos modos de criação e distribuição de conteúdo.

Palavras chave: financiamentos coletivos; análise de conteúdo; jornalismo; kickstarter

RESUMEN

El panorama de los medios ha cambiado drásticamente durante la última década con la aparición de nuevos modelos y plataformas que permiten a los ciudadanos convertirse en periodistas aficionados y editores de noticias. Junto con los jugadores tradicionales, los recién llegados y las iniciativas de bricolaje surgieron en el mercado con la ayuda de plataformas que buscan conectarse con una audiencia potencial y ofrecer medios de financiación alternativos, como el crowdfunding. Los casos de éxito y los ejemplos innovadores abundan en la literatura, a menudo en un análisis basado en casos, que muestra el potencial de este modelo de financiación para apoyar proyectos locales y periodismo de investigación. El objetivo de este documento es revelar descriptivamente las características de tales llamadas a través de un análisis de contenido utilizando el sitio web Kickstarter, ya que este es generalmente un caso representativo del modelo de crowdfunding basado en recompensas en todo el mundo. Este estudio contribuye a debatir no solo las características de las llamadas sino, además, hasta qué punto el crowdfunding parece generar formas novedosas de crear y compartir contenido.

Palabras clave: financiamentos colectivos; análisis de contenido; periodismo; kickstarter

1. Introduction

Journalism media and printed publishing have suffered considerable transitions in the past decades with the advent of digitization and new technologies (Pavlik, 2013). Innovation in format and content opened up a myriad of ways through which information can be spread out. Such innovations usually entail transformations in the funding systems, even though traditional media groups typically remain in the market coexisting with numerous small players of the so-called “niche” markets (Cool & Sirkkunen, 2013). One of the most recent and still underdeveloped innovations in funding systems for all sorts of cultural content comes from crowdfunding initiatives, in which a large number of supporters back the pre-production of content either via subscription or subject to a one-time payment that allows them exclusive access to content.

Crowdfunding is an emerging and still growing system for financing projects of various motivations (Mollick & Kuppuswamy, 2014). It has primarily evolved from the cultural sectors to other areas such as design, technology and, remarkably, journalism and publishing. The literature on crowdfunding had so far delved extensively into the overall characteristics of crowdfunding campaigns across many areas without paying close attention to features within sectors. Much work remains to be done as pointed out by Short et al. (2017). It is our aim to focus on the features of crowd-funding journalism: its main characteristics, results and innovative aspects.

Crowdfunding is a new alternative model that has called the attention of creators for its relatively easy way to overcome demand uncertainty and bypass traditional gatekeepers (Leboeuf & Schwienbacher, 2018). Before making substantial financial commitments, entrepreneurs are able to test the audience’s acceptance for certain products and prevent the risks associated with an unknown demand (Hoffman & Lecamp, 2015). Even with these benefits, not all sectors equally benefit from crowdfunding platforms. On Kickstarter (2019)[1], for instance, journalism projects appear with the lowest success rates[2] (22%) in comparison to the other fourteen areas available on this website. It is worth recognizing, therefore, the patterns within this particular sector and critically assessing its potential to bring about any innovation in formats or content to journalism calls.

This paper unfolds a content analysis as suggested by Neuendorf (2002) in line with the categorization of crowdfunding calls’ features according to our theoretical framework. Our main results point out to a predominance of products with various themes (politics, environmental, social, etc.), largely online distributed, of not-investigative nature and budget-transparent (although without sophisticated information). We aim to contribute to the field of digital journalism and new forms of funding by critically assessing the projects made available on such platforms. The past decades have seen striking innovative practices in journalism with regard to platform development. Those have intended to reach broader audiences without restraining their operations to paper-based news. Notwithstanding, these new platforms do not always unveil relevant, innovative and appealing content for a wider public. Our conclusions draw on the fact that much remains to be done in order for innovative practices to actually emerge and expand.

2. Conceptual Framework

The central concepts supporting our analyses are based on the literature review of (a) what innovation in journalism entails - from the format, content and funding point of view - and (b) definitions of crowdfunding and its relation to innovation. The second section is comprised of our content analysis and discussions about the ways that amateur and do-it-yourself (DIY) project creators had chosen to deliver content.

2.1. What is innovation in Journalism?

It is not a novelty that digital formats had populated the online landscape in all sorts of forms and content, as Bocskowski (2004) contends. From new platforms to special online editions, the world of publishing media has drastically changed during the past decades forcing companies to restructure operations and digitalize content. Oftentimes, this happens in a similar process as compared to traditional media companies, although new platforms bring about additional digitized distribution and fewer intermediaries. Not so often, these changes have happened in the realm of funding schemes as media groups largely rely on reengineering with lean structures. Digitalization allowed this market to become denser as the requisites to start an online media company are lower than the typical media firm. In this sense, journalism potentially becomes more spread with the advent of both independent platforms and large companies that migrate their operations to online environments.

As any innovation is driven by technological advancements and particular socio-economic contexts (Schumpeter, 1949), it is key to seek definitions of what innovation in journalism entails specifically. From a conceptual point of view, innovation in journalism should be tied to quality commitment to quality and high ethical standards (Pavlik, 2013), therefore, subject to the act of professionals and citizen journalists who generate content. In Pavlik’s (2013) point of view, such content is fueled with quality, engagement, digitally optimized, reported with new methods and ethical in its essence. Also, the notion of “sustainable innovative journalism” is supported by a few pillars described, namely: research, commitment to freedom, accuracy, and ethics.

Innovation research in media organizations had been carried through by scholars like Lewis and Usher (2013) and Gynnild (2014) from the perspective of open source initiatives and computational tools. In general, the notion of innovation is associated with that of the “entrepreneur” as a person or a firm that exploits opportunities and transforms them into business with sizable options for profiting (Schumpeter, 1949). It can be observed, however, that not every online initiative is profitable or seek profitability, or even that journalists consider themselves entrepreneurs. Notwithstanding, entrepreneurial journalism has led to a situation of part-time and freelance jobs without social security. Other critical points of view[3] in regard to journalism after digitalization are also present in the literature as for instance in the work of Salamon (2019) which discusses the uncertainties from the lenses on individualism-collectivism action. From that perspective, changes in the creation and distribution of content had transformed the labor market towards the emergence of the freelancer and self-made journalist, in line with do-it-yourself and “long-tail” arguments (Anderson, 2006).

As Storsul and Krumsvik (2013) indicate, media innovation comprises the notions of product innovation, process innovation, position innovation, paradigmatic innovation[4] and social innovation. Taking into account economic and sociological innovation research, Dogruel (2013) points out four characteristics to media innovation: 1) newness; 2) economic or societal exploitation; 3) communicative implications; 4) complex social process. Some of these aspects are more evident than others in online projects, as often bottom-up or “long-tail” producers coming out of niche markets may lack the resources or the intention to build up formal businesses. And so, many journalism projects happen “under the radar”: a market exchange environment regarded as amateur and non-professional.

Furthermore, the last important shift with regard to innovative forms of journalism has come from novel ways of data gathering and reporting information as for instance the manipulation of big data (Lewis, 2015), which requires the development of hard skills (e.g. coding). This seems to be the path forward on data analysis for journalists in the forthcoming decade, considering that the plethora of information requires high levels of curation and organization in order for the common reader to interpret them.

2.2. Crowdfunding and Journalism

New online funding tools, such as crowdfunding, came to address the funding gap for early-stage entrepreneurs with the help of digitalization (Cumming & Hornuff, 2018). Crowdfunding emerges in early 2000 as an innovative way through which entrepreneurs, artists, independent creators and amateurs can rely on “the crowd” to support creative projects and introduce new goods in a market where the access to funds might be restricted to agents who present established quality signals. Crowdfunding is thus considered one of the most important financial innovations due to its novel way of allowing entrepreneurs to access funds that would not be available otherwise (Kuti & Madarasz, 2014). By sharing the risks of a venture and pre-testing demand, entrepreneurs can ideally share content before a product is finalized.

Many are the models through which crowdfunding happens and platforms greatly differ in their goals and services. Reward-based crowdfunding platforms are typically used those who wish to pre-finance their production phase, and reward backers with a product, service or experience instead of profit[5]. If a consistent number of people are involved in this phase, the entrepreneur realizes important goals: market validation, acquisition of funds to financing his activities and information gathering. Commonly, these calls entail an all-or-nothing scheme in which the funds are retrieved to the backer in case the project does not manage to reach its goal. Therefore, there is less uncertainty on the backer’s side who is often pledging funds to an unknown and not yet produced item. Considering the prospective nature of crowdfunding, it is important to portray signals of quality that help to reduce uncertainty and ensure credibility in the eyes of the supporters.

It has been previously discussed that quality signals increase the chance of success in crowdfunding campaigns such as campaign description, visuals, range of rewards, language and others (Mollick, 2014; Lee et al., 2019). Mollick and Kuppuswamy (2014) noticed that entrepreneurs who used crowdfunding for their projects turned out to be very innovative. While innovation is easy to define in some crowdfunding categories (e.g. technology, design), it is harder to distill how we can recognize innovation in journalism, for instance. The possibilities that crowdfunding offers to journalism do not seem different than any publishing endeavor that goes online via crowdsourcing. In line with the literature on the early-stage funding gap (Cumming & Hornuff, 2018), this alternative funding scheme reduces entry-barriers for newcomers, sometimes acting as an “informational tool” (Viotto da Cruz, 2016) for established entrepreneurs who wish to test markets.

Within journalism initiatives, crowdfunding has been timidly discussed with case-studies of very successful endeavors. In 2015, for example, the New Media and Society journal edition (Bennet, Chin & Jones, 2015) innovates in bringing the discussion of crowdsourcing for new media. It laid out the tone of the studies: case-based analyses such as Hills (2015), studies about the moral economy of crowdfunding and civic campaigns examples (Scott, 2015; Stiver et al., 2014) and analyses of the norms of independence and objectivity in producing autonomous journalism content (Hunter, 2015). Oftentimes, the rationale of a socially-driven motivation is discussed in crowdfunding calls as for instance in Koçer (2015) and Davies (2015), which shows a comprehensive social-politically informed concern with regards to the content of the calls[6].

In other areas, the behavior of backers has been widely analyzed as well, often by arguing that the predominance of social motivations, warm-glow and prosocial drive of supporters outweighs the financial and economic aspects of the calls (Dai & Zhang, 2019). Directly or indirectly, this impacts on the way campaigns are portrayed or on potential hints to founders in regards to what are the common success factors of crowdfunding calls. However, little is known in regards to sector-specific patterns, or to which extent certain areas address more or less the so-called “innovativeness” and “socially-driven” components of crowdfunding. This is what we intend to address in the forthcoming sections by first laying out the methodological procedures we had undertaken in this study.

3. Methodology

One of the most known platforms using the reward-based model is Kickstarter[7] (Mollick, 2014) - from which we extracted our data. From its inception, as much as 4 billion USD have been pledged to various creative projects funding more than 155 thousand projects. Up to this point, cultural and creative industries largely use the reward-based model (European Commission, 2017). Kickstarter reinforces that it values innovation, mainly in terms of creativity, and acknowledges its impact on the creative economy which is at the heart of innovation (Kickstarter, 2019). Moreover, Kickstarter is seen by the overall media as a matchmaker for innovation-driven entrepreneurs and innovation-hungry consumers (Mollick, 2016). Our focus, thus, relies on this platform to discuss if that is also applicable for journalism projects and to which extent the so-called positive aspects of crowdfunding are also available on such calls.

3.1. Data collection and Sampling

Our paper follows a content analysis as suggested by Neuendorf (2002) in which we first select the database from which we draw our units of observations, then we clean the database in order to extract the repetitive information and, finally, we categorize each observation with the codebook prepared to analyze the crowdfunding calls. Regarding data collection, all projects were web-scraped on Kickstarter. The web-scraping process focused only on Journalism projects (as selected by a tag with the title “journalism” on the website). This filtering process via the website allowed us to access only our intended sample regardless of the success of calls.

The data collection happened from November to December 2018 and retrieved projects that were already finished or almost finished by using Winautomation software in which a piece of code is developed to navigate through the website in order to collect the HTML source codes of each hyperlink of a project. In total, were collected 294 hyperlinks launched between 2010 and 2018. From these projects, 197 were determined by Kickstarter as successful (reached the goals), 68 as unsuccessful (not reached the goal), 15 as canceled, 13 as live and one as suspended. Considering our aim, we selected only the 197 projects that were successful. With regard to the label journalism applied available at Kickstarter, we primarily relied on the platform’s label and then revised their actual adherence to a journalist content. From our revision of 197 successful projects, 21 were not related to any journalism content[8], two were unavailable (the content was not available for further look anymore) and two were repeated collected links. This resulted in a total of 172 (N) projects to code.

In order to define the sample size required for the intercoder reliability test, we applied an equation proposed by Lacy and Riffe (1996, p.965) with a confidence interval of 95% and an expected 80% of coincidence. As a result, 48 projects were coded by a second coder, besides the usual Content Analysis procedure. The final result was 95,1% of coincidence between coders, which validates the intercoder reliability expected for this sample.

3.2. Coding scheme

With the aim to unveil the main characteristics of successful Journalism calls on Kickstarter seven variables focused on product features (Subtheme, Platform, Format, Launched or Not Launched, Budget transparency and Investigative proposal) were structured. As the rewards could drastically differ between them and the nonjournalistic products (T-shirts, mugs, bags, memorabilia for instance), calls that focus on the latter were not included in this analysis as they do not represent core journalistic products.

The code “Subtheme” was constructed taking into account multiple journalistic sections as Politics, Economy, Health, Environment, Culture, Security, General News, Sports, Education, International, Science, and Travel. As the essential goal as to identify the predominant subtheme for which project added specific sections like Local News, Social Problems, Food, and History. The coding of a project with “More than one” or “Unclear” tags, which excluded the need for the choice of a single subtheme by the coder, was also allowed. In general, we looked into both the texts and rewards offered by the calls in order to determine the main theme under scrutiny. Even though oftentimes the calls offer various products, our focus was on the journalistic content.

Given that news’ formats of storytelling are considered as a territory of innovation in Journalism (Pavlik, 2013), variables like “Platform” and “Format” were structured, respectively, to represent projects developed only via online, offline or both means; and to identify the predominance of the content format (text, photograph, video or audio). Specific cases in which the product was previously available to the audience were treated distinctly, considering that backers could access the product and decide to support them or not. Therefore, all the projects were categorized into two options: Launched or Not Yet Launched. Calls whose projects were said to exist already were categorized as “Launched”, which means that founders requested funds to implement specific features or expand it. “Not Yet Launched” referred to projects that requested upfront funds in order to start up after the goal was reached.

Another feature that could influence the donations is the “budget transparency” - as this is a relevant item for crowdfunding projects (Carvajal et al, 2012). The distinct features of transparency (percentage of spend, use of infographics, name of providers, for instance) were not taken into account, although different levels of transparency in our sample (e.g. calls that specified any destination for resources were coded as transparent, which means that we do not critically assess whether the intended level of transparency is sufficient or not) were recognized. Thus, the goal was to observe if the projects at least informed the way in which money would be spent afterwards.

As for the last code “Investigative journalism” we searched for information that would detail the intention of the project founders regarding covering topics of special interest such as: politically or socially driven investigations, any content of public interest that could entail a broad social relevance. Based on the premise that ensuring the long-term viability of news refers to the quality of content - particularly accuracy in reporting truth (Pavlik, 2013) - our sample was coded with a variable called “Investigative Proposal”.

The coding scheme was applied to all projects based on the reading of their descriptions and rewards. This process was defined by following guidelines from previous literature that analyzes calls based on the explicit content, without doubleguessing or morally questioning the extent to which the text is trustworthy or not[9]. We followed the same approach also because it is virtually impossible to tell if project founders delivered the promised products as expected only based on the latent content displayed via the platform by doing a cross-sectional study.

Furthermore, the analysis unfolds in two ways. First, by presenting the descriptive results of the calls (frequencies and percentages), to later, then, discuss the relevance of such results in light of the literature we presented above. The analysis aims at both providing the features of the calls and critically assessing what it means for journalism as a field of studies and occupation to rely on alternative funding tools such as crowdfunding.

4. Main descriptives

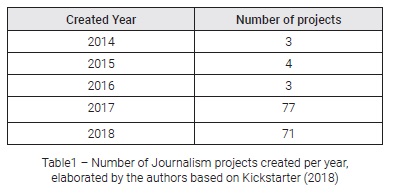

In this section, we unfold the basic descriptive of our sample and its distribution which are divided into the following aspects: timeframe, geographical locations, themes, platform (online/offline), and media delivered. Furthermore, we describe specifically the features related to transparency and investigative proposals. Regarding the projects’ creation date (Table 1 ), the majority (n=148) was launched in the most recent years: 2017 and 2018. Even considering the accumulated stock of projects until 2016, this subtotal (n=24) does not reach half of the 2017 project volume. We see, therefore, an increasing interest in this funding model probably pushed by the increasing number of publications (academic and non-academic) about the matter. Similar patterns are seen in other cultural and creative industries as the statistics on Kickstarter (2019) website shows.

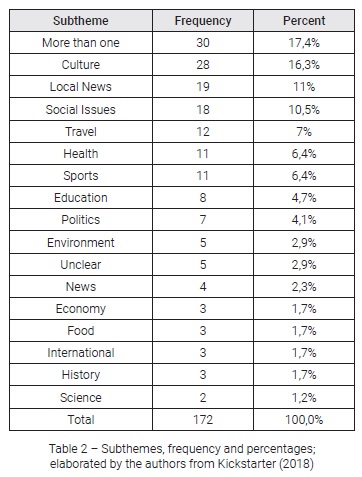

In what comes to geographical location, the prevalence of projects from the United States is noticeable in comparison with all the other countries in the sample, consistent with the origin of the analyzed platform. There are 103 projects from distinct regions in the US, 28 projects from the United Kingdom and only seven from Canada. Followed by Sweden (6), Mexico (4), Germany (3), Australia (2), France (2) and other countries with just one project. As shown in Table 2 below, despite the prevalence of projects classified with “More than one” subtheme, Culture was identified as the most frequent single subtheme with 16,3% of the cases, followed by Local News (11%) and Social Issues (10,5%).

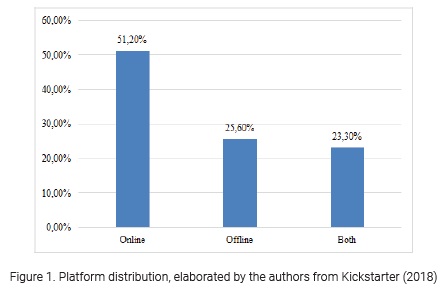

Figure 1 below shows the prominence of digital products (51,2%) which is a remarkably balanced result for a media that mostly depends on online interactions. This typically means that having an online funding tool does not necessarily result in online products.

5. On the formats of the calls: the media and its products

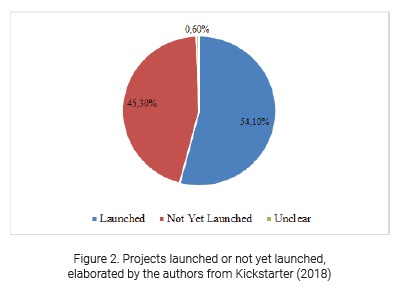

Figure 2 below depicts the breakdown information between projects that involved existing products and others that appeared for the first time online. As the image shows, a predominance of existing cases is at stake denoting possibly lower levels of innovation in those cases.

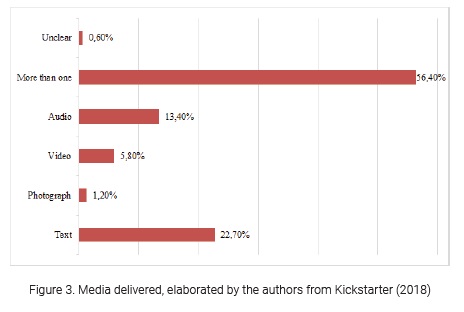

The proportion of launched products at the moment of the crowdfunding campaign creation is higher in the case of online products (59,1%) as compared to 38,6% in the case of offline products. These numbers, however, vary regarding the media being put forward and the theme chosen by the project founder. Our descriptive data shows that the majority chooses more than one type of content format, generally text, and audios in the form of podcasts. Our review of projects on Figure 3 shows that there is a relevant sample of projects that use podcasts[10] accompanied with video to release their content, in line with existing distribution available through YouTube. On the other hand, such devices are also complementary as they allow for monetization of pre-existing projects.

6. On the content of the calls: investigative and transparent components

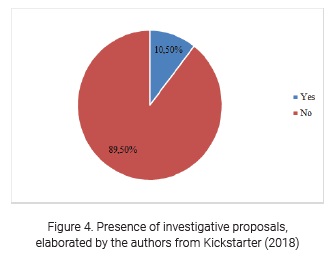

Transparency and investigative journalism are often cited as important features of digital journalism (Franklin, 2014). Whilst many media groups indeed embrace these principles, we aimed to understand if the crowdfunding calls were also adhering to it. As for the investigative component, we do not see a relevant societal contribution being made in this case as the public good aspect of the calls is fairly absent (see Figure 4). Despite the narratives of democratization of access to finance and the possibility that local initiatives take over the blank spaces left by traditional media groups - which comes along with crowdfunding schemes - this rationale does not seem to be applicable in the case of our projects. However, we note that, whenever an investigative component was present, they referred to politics and social causes, which boosted the appeal of the call and potentially engaged largely with the audience.

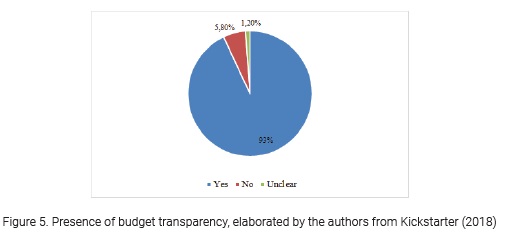

Our coding on budget transparency was designed to detect any mentions of how crowdfunded resources would be spent[11]. As our standard was deliberately set as very low, the majority appears as transparent in Figure 5. We must critically observe that because the coding considered any slight evidence of transparency as the presence of transparency, the projects that showed the destination of the funds in a fairly limited way, such as simply mentioning the main destination of the resource, were deemed transparent. Rarely in the analyzed sample, founders dedicated time to display percentages of any detailed information about the usage of the money. Even more scarce are the projects that display graphics and visualization to increase the credibility of the call. We hypothesize that such behavior can be rooted in two main reasons: (a) credibility happens outside the online call so that founders have their own social network that supports the project despite the low levels of transparency, and (b) project founders may simply not know how to manage transparent communications with the audience. However, this would require further verification in future researches.

7. The path forward: future concerns on crowd-funding Journalism

The future of journalism is often portrayed as part of a digitalized world in which content is created and distributed via online means. The inescapable “age of digital media” (Franklin, 2014) shows that every aspect of the production, reporting, and reception of news is changing for the businesses of news. Oftentimes, this changing landscape of media production also puts into perspective the role of big players, traditional media companies and businesses that had to change their operations in order to adapt themselves to a new environment.

What this study unveils is that, first of all, audiences not only decide to engage with media but to also create content themselves: this is what typically defines amateurism movements in the process of becoming professionalized and seeking for funds (even if limited) to better realize their goals. Creators act on that in their own platforms, social media, and websites. However, as this is typically a sidetrack from their main occupation, media products such as the ones observed in our database see in crowdfunding a possibility to fund a small initiative quickly, even though the financial rewards of such campaigns are generally low[12].

Consequently, this funding tool shows certain benefits and limitations that we intend to suggest for journalism practice[13]. On the positive side, crowdfunding journalism projects allow the democratization of media production and the diversification of the market by means of more competition. The democratization principle has been already discussed regarding crowdfunding, even though not specifically in Journalism (Mollick & Robb, 2016). If extended to media production, it simply means that more people get the chance to distribute news and minimally fund operations even though the majority do not seem to act professionally in the field of journalism. This reinforces the argument that new media journalism is increasingly made with multiple revenue streams, low-pay or even no-pay content (Franklin, 2014). Furthermore, this argument comes attached to more individual labor structures (Salamon, 2019) often criticized as “neoliberal” in essence and erratic, which may, to a certain extent, harm the muchneeded financial sustainability of content production and distribution - especially in the case of investigative journalism.

Journalism calls seem to be widely supported in donation-based examples that show local audiences interacting with small-scale media production. This also possibly means that the sustainability of self-funded journalism made within crowdfunding is extra-dependent on close social networks interested in the topic. We assume that in many cases, agents remain doing amateur journalism as an occupation based on volunteer purposes, this way not so often reaching other domains. Our analysis of budgetary transparency reveals zero projects requesting money for their own labor, which means that only distribution costs are covered, and projects’ continuation might be uncertain.

Furthermore, the product innovation component seems to be fairly limited and does not necessarily translate into innovation in news content. For example, zero projects entailed any big data component - a feature of the so-called future of journalism. We cannot conclude surely if this is the case from our sample due to the limitations of our coding strategy. Moreover, the presence of innovation in ways of gathering information is mostly absent, which makes us interpret that the medium per se (the crowdfunding platform) may not replace the lack of process and product-oriented innovative drive. When innovation traces appeared in our sample, they referred to allowing more parties to also collect information - in line with crowdsourcing or cocreation initiatives[14] Given that the discussion of product innovation and financial sustainability aspects come as consequences of our study but not as a purely coding strategy, we suggest that more research should be conducted in order to fully verify the features that impact in the alternative content production also from external factors, outside the realm of information available on platforms. In this sense, external quality components, social network influences and previous career evidence may possibly undermine or enhance the possibilities that certain projects become more successful than others, or that some calls depict more sustainability and innovation than others in their forms and content.

Conclusions

This paper aimed at describing the features of crowdfunding calls for Journalism comprehensively including almost all the databases on Kickstarter for this category. Via a content analysis, we coded units of observation in order to evaluate a series of aspects: themes, transparency, digital or non-digital content, pre-existing products and novelties. We observed a predominance of some level of transparency (even though not sophisticated), a majority of online releases, and non-investigative cases in nature. This unveils an interesting field for further research given that: (a) a number of aspects were not covered in our study (e.g. the memorabilia offered alongside the journalistic product), and (b) the nature of the journalism work funded via these platforms is yet to be discovered: motivations, difficulties, reasoning and, most importantly, if this is a central or peripheral occupation in the project founders’ perspective. Even though our study does not delve into these specificities, it shows that empirically there is still fundamental research to be done in order to be able to portray the features of do-it-yourself publishing.

The study also shows that alternative funding schemes such as crowdfunding are increasingly accessed and that, even though the sustainability of the model is still debatable, it does offer concrete options for start-up initiatives that might become profitable firms or non-profit media institutions. Some of these initiatives, although, may simply remain as single projects and amateur production withholding their own value, which should not be seen as undermining the value of a democratic funding tool. In a nutshell, even though the quality and variety of projects are wide, consumers and enthusiasts both benefit from having more options than less available for pre-purchase. Nonetheless, the extent to which such developments may happen in this dynamic market still remains to be seen. Our research, so far, points out a few aspects to further observe both empirically and theoretically, mostly in relation to the contexts, peculiarities and consequences of digitalizing news via democratization of production.

REFERENCES

Anderson, C. W., Downie, L., & Schudson, M. (2016). The news media: What everyone needs to know. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Anderson, C. (2006). The long tail: Why the future of business is selling less of more. New York: Hyperion. [ Links ]

Belleflamme, P., Lambert, T., & Schwienbacher, A. (2014). Crowdfunding: tapping the right crowd.Journal of Business Venturing, 29(5), 585-609. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.07.003. [ Links ]

Bennett, L., Chin, B., & Jones, B. (2015). Crowdfunding: A New Media & Society special issue.New Media & Society, 17(2), 141-148. DOI: 10.1177/1461444814558906. [ Links ]

Bocskowski, P.J. (2004). Digitizing the News: Innovation in Online News Organizations. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.

Carvajal, M., García-Avilés, J.A. & González, J.L. (2012). Crowdfunding and Non-profit Media. Journalism Practice, 6(5-6), 638-647. DOI: 10.1080/17512786.2012.667267. [ Links ]

Cook, C. & Sirkkunen, E. (2013). What’s in a Niche? Exploring the Business Model of Online Journalism. Journal of Media Business Studies, 10(4), 63-82. DOI: 10.1080/16522354.2013.11073576. [ Links ]

Cumming, D. & Hornuf, L. (Eds). (2018). The Economics of Crowdfunding, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dai, H., & Zhang, D. J. (2019). Prosocial Goal Pursuit in Crowdfunding: Evidence from Kickstarter.Journal of Marketing Research, 56(3), 498-517. DOI: 10.1177/0022243718821697. [ Links ]

Davies, R. (2015) Three provocations for civic crowdfunding. Information, Communication & Society, 18(3), 342-355. DOI: 10.1080/1369118X.2014.989878. [ Links ]

Dogruel, L. (2013). Opening the Black Box - The conceptualising of Media Innovation. In T. Storsul & A. H. Krumsvik (Eds), Media Innovations - A Multidisciplinary Study of Change (pp. 29-43). Göteborg: Nordicom. [ Links ]

European Commission (2017). Crowdfunding: reshaping the crowd’s engagement in culture, Retrieved from https://europa.eu/capacity4dev/crowdfunding/documents/new-report-crowdfunding-reshaping-crowds-engagement-culture. [ Links ]

Franklin, B. (2014). The Future of Journalism In an age of digital media and economic uncertainty. Journalism Studies, 15(5), 481-499. DOI: 10.1080/1461670X.2014.930254. [ Links ]

Gynnild, A. (2014). Journalism Innovation Leads to Innovation Journalism: The Impact of Computational Exploration on Changing Mindsets. Journalism, 15(6), 713-730. DOI: 10.1177/1464884913486393. [ Links ]

Hills, M. (2015). Veronica Mars, fandom, and the ‘Affective Economics’ of crowdfunding poachers. New Media & Society, 17(2), 183-197. DOI: 10.1177/1461444814558909. [ Links ]

Hoffman, J. & Lecamp, L. (2015). Independent Luxury: The four innovation strategies to endure in the consolidation jungle. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Hunter, A. (2015). Crowdfunding independent and freelance journalism: Negotiating journalistic norms of autonomy and objectivity. New Media & Society, 17(2), 272-288. DOI: 10.1177/1461444814558915. [ Links ]

Kickstarter (2019). Kickstarter. Retrieved from https://www.kickstarter.com/ [ Links ]

Kickstarter (2019). Kickstarter Stats. Retrieved from https://www.kickstarter.com/help/stats?ref=hello [ Links ]

Kim, P. H., Buffart, M., & Croidieu, G. (2016). TMI: Signaling credible claims in crowdfunding campaign narratives. Group and Organization Management, 41(6), 717-750. DOI: 10.1177/1059601116651181. [ Links ]

Koçer, S. (2015). Social business in online financing: Crowdfunding narratives of independent documentary producers in Turkey. New Media & Society, 17(2), 231-248. DOI: 10.1177/1461444814558913. [ Links ]

Kuti, M. & Madarász, G, (2014). Crowdfunding. Public Finance Quarterly, 59(3), 355-366.Retrieved from https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:pfq:journl:v:59:y:2014:i:3:p:355-366 [ Links ]

Lacy, S. & Riffe, D. (1996). Sampling Error and Selecting Intercoder Reliability Samples for Nominal Content Categories. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 73(4), 963-973. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769909607300414 [ Links ]

Leboeuf, G. & Schwienbacher, A. (2018). Crowdfunding as a New Financing Tool. In D. Cumming & L. Hornuf (Eds.), The Economics of Crowdfunding: Startups, Portals and Investor Behavior (pp. 11-28). NY: Springer Publishing. [ Links ]

Lee, C., Bian, Y., Karaouzene, R. and Suleiman, N. (2019). Examining the role of narratives in civic crowdfunding: linguistic style and message substance. Industrial Management and Data Systems, 119(7), 1492-1514. DOI: 10.1108/IMDS-08-2018-0370.

Lewis, S. (2015). Journalism in an Era Of Big Data. Digital Journalism, 3(3), 321-330. DOI: 10.1080/21670811.2014.976399. [ Links ]

Lewis, Seth C., and Usher, N. (2013). Open Source and Journalism: Toward New Frameworks for Imagining News Innovation. Media, Culture & Society, 35(5), 602-619. DOI: 10.1177/0163443713485494.

Mollick, E. (2014). The dynamics of crowdfunding: determinants of success and failure. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(1), 1-16. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.06.005. [ Links ]

Mollick, E. (2016). The unique value of crowdfunding is not money-it’s community. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2016/04/the-unique-value-of-crowdfunding-is-not-money-its-community [ Links ]

Mollick, E. & Kuppuswamy, V. (2014). After the Campaign: Outcomes of Crowdfunding. UNC Kenan-Flagler Research Paper No 2376997. DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.2376997. [ Links ]

Mollick, E., Robb, A. (2016). Democratizing Innovation and Capital Access: The Role of Crowdfunding. California Management Review, 58(2), 72-87. DOI: 10.1525/cmr.2016.58.2.72. [ Links ]

Neuendorf, K. A. (2002). The content analysis guidebook. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Pavlik, J.V. (2013). Innovation and The Future of Journalism. Digital Journalism, 1(2), 181-193. DOI: 10.1080/21670811.2012.756666. [ Links ]

Salamon, E. (2019). Digitizing freelance media labor: A class of workers negotiates entrepreneurialism and activism. New Media & Society, 22(1), 105-122. DOI: 10.1177/1461444819861958. [ Links ]

Schumpeter, J.A. (1949). Economic theory and entrepreneurial history. In Wohl, R. R. (Ed.), Change and the entrepreneur: postulates and the patterns for entrepreneurial history, Research Center in Entrepreneurial History. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Stiver, A., Barroca, L., Minocha, S., Richards, M., & Roberts, D. (2015). Civic crowdfunding research: Challenges, opportunities, and future agenda. New media & society, 17(2), 249271. DOI: 10.1177/1461444814558914. [ Links ]

Storsul, T., & Krumsvik, A. H. (2013). What is media innovation? In T. Storsul & A. H. Krumsvik (Eds), Media Innovations - A Multidisciplinary Study of Change (pp. 13-26). Göteborg: Nordicom. [ Links ]

Scott, S. (2015). The moral economy of crowdfunding and the transformative capacity of fan-ancing. New Media & Society, 17(2), 167-182. DOI: 10.1177/1461444814558908. [ Links ]

Short, J. C., Ketchen, D. J., McKenny, A. F., Allison, T. H., & Ireland, R. D. (2017). Research on Crowdfunding: Reviewing the (Very Recent) past and Celebrating the Present. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(2), 149-160. DOI: 10.1111/etap.12270. [ Links ]

Viotto da Cruz, J. (2018) Beyond Financing: Crowdfunding as an Informational Mechanism. Journal of Business Venturing, 33(3), 371-393. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.02.001. [ Links ]

Received | Submetido: 2019.10.30. Accepted | Aceite: 2020.04.20.

Biographical notes

Carolina Dalla Chiesa is PhD candidate and Lecturer and Cultural Economics where she researches funding models and tools for the creative sectors. She teaches and researches the Economics of Creative Industries and the role of Digitalization in arts-related products.

Email: dallachiesa@eshcc.eur.nl

Address: Burgemeester Oudlaan 50, 3062 PA Rotterdam

Mariana Scalabrin Müller is a PhD candidate at Doutoramento FCT: Tecnologia Cultura e Sociedade with the support of FCT Foundation. Master in Communication Science from Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS).

Ciência ID: F410-7B6F-CD6F. Email: marianasmuller@gmail.com

Address: Universidade do Minho, Centro de Estudos de Comunicação e Sociedade, Campus de Gualtar - 4710-057 Braga, Portugal

Notas

[1] Further statistics can be checked on the website: https://www.kickstarter.com/help/stats

[2] Success rates are defined as the percentage of projects that manage to reach their goals faced a total of successful and unsuccessful calls.

[3] Even though we critically assess the extent to which crowdfunding seems to innovate journalism, our focus does not lay on understanding the rationale behind the freelance worker, but to generally observe latent patterns in crowdfunding calls

[4] The notion of Business model innovation (including the use of funding tools) is considered a type of paradigmatic innovation according to this framework.

[5] Belleflamme et al (2014) distinguish crowdfunding between the profit-sharing schemes and the pre-ordering calls. Both greatly differ in their economic and managerial consequences. The second type is what we call “reward-based” as the result of a contribution is the good itself, not its future success. In some cases, calls also include memorabilia and ancillary rewards to the main product offered.

[6] For Carvajal, García-Avlles and Gonzales (2012) this is represented in the emergence of new media models interested in preserving the public interest of journalism via non-profit institutions and community-funded platforms.

[7] The US-based platform Kickstarter (2018a) typically accepts projects related to all cultural and creative industries without barriers as long as projects abide by legal regulations.[8] For that, we use the definition of Anderson, Downie and Schudson (2016, p.60-61) in order to support what is a journalism product: “...news is not necessarily journalism, in which newsworthy information and comment is gathered, filtered, evaluated, edited, and presented in a credible and engaging forms, whether writing, photography, video, or graphics. At its best, journalism puts the news into context, investigates, verifies, analyzes, explains, and engages. It embodies news judgment oriented to the public interest.”.

[9] Previous literature has focused, for instance, in linguistic cues and signals of credibility via quantitative studies (Kim, Buffart & Croidieu, 2016; )[10] One remarkable example is of the Kenyan football documentary, released in the form of a podcast, available at: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/693974637/kenyan-football-unveiled-a-podcast-documentary

[11] As such, budget transparency can be seen as limited given that just mentioning the desired destination of funds may not be sufficient to express credibility. The lower importance of this item could, then, entail that consumers trust more on these projects possibly due to close social networks.

[12] In most cases, reward-based projects in our database do not fund labor. Consequently, activities such as these potentially remain within the realm of self-funded ideas rarely becoming a business or accessing any funds otherwise.

[13] The pros and cons of crowdfunding in general as a funding scheme has been already well discussed by Mollick (2014), Agrawal et al. (2014), and Belleflamme et al. (2014), widely cited papers in crowdfunding literature.

[14] One remarkable example is the project “In Focus” (available at: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/939655723/infocus) that gave cameras to homeless people in order to incentivize them to produce creative content, and, furthermore, share it.