1. Introduction

Social issues have influenced companies’ business strategies from a very early age, and the relationship between business and society has been addressed both in academia and in the business world (Carroll, 2008).

Since the 30s of the last century voices that extolled the fact that companies have obligations to the society in which they operate began to be heard in academic circles. Such forecasts included the works of C. Barnard (1938), J.M. Clark (1939) or H.R. Bowens (1953). At this point, in the business world, companies began to implement policies to address the social concerns of their clients, labour force, and the community, both in the United States of America (USA) and in Europe (Heald, 1970). The concept of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) began to be applied, with initiatives such as cause-related marketing, in which companies support a specific non-profit organization or social cause with a percentage of the company’s sales (Barone et al., 2000; Varadarajan & Menon, 1988), and even with companies addressing issues unrelated to their core businesses, such as the environment (Boyhan, 1992), or racism (di Norcia, 1989). Initially, these activities were an exception within the marketplace, but more recently companies began to realize the need and duty to assume a broader and stronger role in society (Korschun, 2021; Moorman, 2020).

Ample evidence suggests that consumers and other stakeholders care not only about brands being accountable for their actions, but also about brands having a strong position on the most current issues that affect society (e.g., Mason & Simmons, 2014; Skoglund & Böhm, 2019). This translated into a greater number of brands exposing a stance on problems such as gender inequality, discriminatory labour practices or environmental damages, and taking action to minimize or solve them - a phenomenon called brand activism (Sarkar & Kotler, 2018). Considering the great interest of the business world in this new strategy and the ways in which brand activism actions can generate positive outcomes for companies (e.g., Chatterji & Toffel, 2019; Kim et al., 2020), it is unsurprising that brand activism appears in a growing stream of research (American Marketing Association, 2021). However, most brand activism studies tend to describe the phenomenon itself and analyse its potential effects on brand performance and image, without establishing which factors contribute to the success or failure of these strategies.

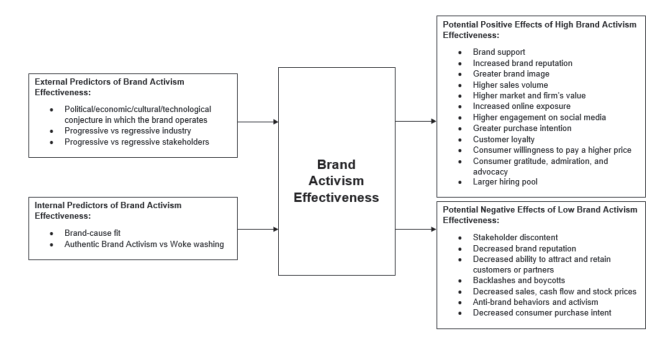

In response to this gap, this article introduces a working model that specifies the main predictors that contribute to the effectiveness of brand activism in a century of globalization and intense debate on socio-political issues, based on a literature review of the most prominent research in the field. Likewise, the working model also proposes potential positive and negative effects of these strategies, thus contributing to broaden the scope of analysis of this phenomenon and to a deeper understanding of what really underlies brand activism. The article begins by describing the background that contributed to the emergence of brand activism, then addressing brand activism as a theoretical construct. Subsequently, the theoretical model of brand activism effectiveness is proposed, which encompasses the predictors and potential effects of brand activism. For each factor, a summary of the theoretical foundations that inform its relevance to the effectiveness of brand activism is provided. Finally, the article concludes about the current challenges of this strategy and how companies can more effectively address social issues based on the discussion of the proposed framework, also developing some important directions for future research in the area.

2. Theoretical Underpinnings: The rise of Brand activism

2.1 General background

A range of factors has highlighted the need for companies to adopt socially responsible behaviour and get involved in the defence of socio-political issues. One of the most relevant is the growing stakeholder’s demands for a more responsible way of doing business (Shetty et al., 2019).

Driven by the current social inequalities and environmental catastrophes and by the greater ease of making their demands heard through the web, consumers - particularly Millennials and Generation Z - are becoming more ethically driven and showing increasingly concerns about the social and environmental policies of companies (Dauvergne, 2017; Wright, 2020). Consequently, there has been frequent consumer backlashes or boycotts to companies considered socially irresponsible (Cammarota & Marino, 2021). Likewise, if previously many workers did not show great concern with social issues or assumed that these matters were a duty of the State, nowadays employees increasingly seek to identify themselves morally with the companies they work for (Bashir et al., 2012), worrying about the social and environmental impacts of their employers (Skoglund & Böhm, 2019) and desiring to be involved in the corporate so-

cial actions and decisions (Tao et al., 2018).

For its part, while shareholder activism has mostly been interpreted in terms of returns on investment, the rise in shareholder activism over the years has also been driven by social and moral concerns (Rehbein et al., 2004). In addition, stockholders increasingly prefer to invest in socially responsible funds, recognizing these companies as economically more attractive (Rahim et al., 2011), suppliers feel more motivated to work with socially responsible companies (Mason & Simmons, 2014) and communities better accept companies with socially responsible practices (Bertoncello & Junior, 2007).

In addition, the participatory culture, enhanced by the development of new Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) and defined by individual active consumption, co-creation and feedback practices, gains a leading role in consumers’ purchasing decisions, as well as in consumer movements, resistance, activism, and anti-consumption (Kozinets & Jenkins, 2021). According to Goodyear (1999), the growing participation and dialogue between consumers and companies (a process called “consumerization”), translated into relational paradigms of proximity, interactivity and equality, led to greater consumer interest and attention to the company’s actions in the world. These new communication models, enhanced by ICT, also allowed for the personalization of brands, that is, the conception of companies and brands as an entity holding meanings, values, identity, personality, cultural positioning and purposes, and acting on an ethical level (Aaker & Fournier, 1995). In this way, brands increasingly represent points of reference in consumers’ self-identities, transmitting symbolic meanings that consumers seek to express or reinforce their psychosocial identity and self-concept (Morhart et al., 2015). As a result, consumers establish relationships with brands more often in a similar way to their social relations, assuming expectations identical to peer relationships (Bruhn et al., 2012), being also more demanding in relation to the conduct of companies, even in sociopolitical terms (Korschun, 2021).

Thus, brands began to realize the need to stand out in social terms, taking a public position on the main social causes to improve their performance and gain public support (Vredenburg et al., 2020).

2.2 Brand activism as a core construct

Brand activism has emerged as a new strategy by which companies take a clear stand on the most varied issues that affect current societies (Mukherjee & BanetWeiser, 2012). One of the most cited definitions of the concept was given by Sarkar and Kotler (2018, p. 570), who defined it as the “business efforts to promote, impede, or direct social, political, economic, and/or environmental reform or stasis with the desire to promote or impede improvements in society”. In this way, an activist brand can act in multiple issues, including social, legal, economic, environmental, political and workplace subjects, either in a progressive or conservative manner (Sarkar & Kotler, 2018; Vredenburg et al., 2020).

From an organizational perspective, Sarkar and Kotler (2018) see brand activism as a natural evolution of CSR and Environmental, Social and Governance programs, but while these two strategies are marketing/corporate-driven, brand activism is driven by society and its values. Thus, while CSR focuses on what it means to be a good corporate citizen, brand activism focuses on the biggest and most pressing issues facing society, which requires companies to keep up to date with the most recent concerns of their stakeholders (Paine, 2020). At the same time, while CSR policies are usually part of a business strategic plan, brand activism often concerns sporadic or accidental actions (Mukherjee & Althuizen, 2020). In addition, activism goes beyond the company fulfilling its social responsibility to involve advocacy, as companies proactively seek to change public opinion, trying to raise awareness and galvanize additional support around the issue, for example by trying to get support from activist groups or other institutions (Manfredi-Sánchez, 2019).

Nowadays, more and more companies take an activist role by openly expressing their views about socio-political issues (Shetty et al., 2019), not only through their communication campaigns, but also through concrete actions that contribute to minimize these problems, such as donating to the cause, lobbying for the cause or adopting internal practices that support the cause (Wright, 2020). The interest in this new approach is also evident in academia, with recent directives from the American Marketing Association (2021) and the Marketing Science Institute (2020) supporting the need to investigate this phenomenon as a way to better understand it and face the challenges of the 21st century. In fact, despite the great attention to this area in recent times, brand activism still remains a non-consensual concept in the business world and academics have shown some discrepancies in the definition of the concept, with researchers defining it as a society-driven strategy (Sarkar & Kotler, 2018), a communication strategy (Manfredi-Sánchez, 2019), a marketing (Pimentel & Didonet, 2021; Vredenburg et al., 2020) or public relations strategy (Piralova et al., 2020), a product strategy (Screti, 2017), a positioning strategy (Koch, 2020), or as encompassing cultural aspects, ignoring political ones (Shetty et al., 2019). Furthermore, the term has taken on multiple designations, such as Brand Activism (e.g., Koch, 2020; Sarkar & Kotler, 2018), CEO Activism (e.g., Chatterji & Toffel, 2019), Corporate Activism (e.g., Corcoran et al., 2016; Eilert & Cherup, 2020), Commodity Activism (e.g., Mukherjee & Banet-Weiser, 2012), Woke Brand Activism (Mirzaei et al., 2022) or Corporate Sponsored Social Activism (Mcdonnell, 2016), which proves its freshness as a marketing phenomenon and the need for more research in the area (Morgan et al., 2019).

3. Towards a model of brand activism effectiveness

Given the importance that brand activism has gained in recent years, it is essential to understand which factors contribute to the participation of brands in an age of activism and to the effectiveness of their activist campaigns, as well as the potential benefits and risks of this strategy for companies. A diagram of the proposed brand activism effectiveness model is shown in Figure 1, being divided into four basic components: External predictors of brand activism effectiveness; Internal predictors of brand activism effectiveness; Potential positive effects of high brand activism effectiveness; Potential negative effects of low brand activism effectiveness.

External predictors of brand activism effectiveness include factors external to the company and its leaders that can affect a brand’s propensity to support activist movements or extend its social responsibilities, and the sources of its ability (or lack of ability) to successfully engage in such strategies.

Internal predictors are discussed as the factors that solely depend on the brand’s activist conduct to determine the extent to which its activist strategies will be successfully implemented. These factors do not imply a brand’s ability to activism, but the way it manages these strategies.

Potential positive effects of high brand activism effectiveness concern the beneficial outcomes, already addressed in the literature, that effective activism strategies can bring to brands by causing a positive response from their stakeholders.

The model also includes some potential negative effects when brand activism effectiveness is low, which are related to the negative outcomes of an ineffective brand activism strategy, including negative responses from all stakeholder groups.

External and internal predictors thus forecast the effectiveness of brand activism actions and, indirectly, their effects, by predicting the propensity of brands to engage in activist actions and the way stakeholders perceive brand activism campaigns. On the other hand, brand activism can have positive effects (when the effectiveness of the activist strategy is high) and negative effects (when the effectiveness is low). At its core, the Brand Activism Effectiveness model’s argument is that brand activism effectiveness is motivated by a series of factors related to the external and internal environment of the brand, which must be in favourable conditions to promote the success of a brand’s activism actions. The degree of this effectiveness (high or low) will, in turn, imply whether the brand will obtain positive or negative results from its activist campaigns. Scholars have found ample evidence for the links established in the Brand Activism Effectiveness model. In the following sections, each dimension of the four main components of the model and their respective links to the effectiveness of brand activism will therefore be specified.

3.1 External predictors of brand activism effectiveness

Considering the external brand environment, the decision to participate or not in activist movements and the respective results are influenced by various macroenvironmental and market characteristics in which the company operates (Pimentel & Didonet, 2021; Shah et al., 2013).

Historically, the USA has taken a superior position in research development and practical application of CSR, the concept from which brand activism evolved (Matten & Moon, 2008). As such, American companies more explicitly embraced their responsibilities to society through voluntary programs and, more recently, through activist campaigns (Chatterji & Toffel, 2018). In other regions, such as Europe, CSR has taken on a less voluntary and individual nature, with these actions being more associated with values, rules or laws that result in requirements for companies to address stakeholder issues and define their social obligations (Matten & Moon, 2008). On the other hand, in developing countries, CSR assumes, mainly, a philanthropic character (Jamali & Mirshak, 2007).

The greatest power of American companies to address social issues is related to a political, economic, and cultural system that allows greater incentives for companies to play a relevant role in socio-political causes. State power tends to be greater in Europe than in the USA (Lijphart, 1984), and many European companies have economic relationships with governments, benefiting from public investments, while private investment is relatively higher in the USA, where the stock market is the main funding source for companies (Coffee, 2001). In addition, Pasquero (2004) argued that the social responsibilities of American companies are embedded in American culture, particularly in the traditions of individualism, democratic pluralism, moralism, and utilitarianism, while in Europe these responsibilities are embedded in social or labour protection regulations. In this way, it is more common to see ferocious brand activist actions in the USA than in other regions, for example involving economic pressures on states to reject or overturn legislation, or whether governors sign or veto bills (Chatterji & Toffel, 2018).

Additionally, the diffusion and effectiveness of corporate activist movements is also affected by discrepancies in the diffusion, availability and use of the internet around the world and by the consequent capacity of citizens and brands to participate in the Information Age (Chen & Wellman, 2004). Nowadays, activist brands increasingly turn to digital platforms to get involved in the struggle for socio-political changes, interact with their target audience in defense of certain causes and receive feedback from their brand activism campaigns (Gray, 2019; Shah et al., 2013). However, the digital divisions that accompany the diffusion of the Internet create some disparities which make it easier for some brands to participate in social movements and affect the results of their activism strategies. The so-called “digital divide” refers to the existing gap between individuals that have the resources to participate in the Information Age and those who do not (Chen & Wellman, 2004). This gap is characterized by two crucial factors: the possibility and quality of access to the Internet, and digital literacy, which is very unequal between developed and developing countries (Chetty et al., 2018). The existing constraints on the online network and the contextual economic, social and political differences between countries can not only affect the ability of brands to engage in activism, being more feasible for brand activism movements to emerge in democratic societies, with greater education, higher economic power and higher technological development (Shah et al., 2013), but it can also impact the results of brand activism campaigns. The effectiveness of brand activism can be negatively affected, for example, when approaching info-excluded audiences that, in this way, become difficult to reach, convince and mobilize through digital media (Campos et al., 2016). Still regarding external predictors, the industry in which the company operates can also affect its availability to embark on brand activism actions, as well as the effectiveness of these actions, given the greater or lesser pressure of stakeholders for the company to give an opinion and act to resolve sensitive issues (Pimentel & Didonet, 2021). For example, there are certain types of industries, such as the tobacco industry, which may be evaluated as more regressive and will not suffer so much pressure from their stakeholders to take a stand on topics such as health (Sarkar & Kotler, 2018). This greater or lesser pressure for companies to get involved in activism is also related to the characteristics of the brands’ stakeholders, which can be more progressive or conservative (Sarkar & Kotler, 2018). In fact, there are still many consumers who believe that a brand should not take a political position, promote socio-political ideas or get involved with them, which can result in a negative feeling towards activism campaigns (Cammarota & Marino, 2021). In this way, the alignment of activist actions with the values of key stakeholders, especially consumers, reduces the risks of brand activism (Korschun, 2021), as individuals tend to consider their beliefs and moral values as the prevailing, making it extremely difficult for them to change their beliefs to align with those of the brand or to accept views that are completely opposite to their own (Mukherjee & Althuizen, 2020). This point is supported by previous studies, which have shown that consumers’ negative emotions towards brands can result from a variety of reasons, including political motivations (Sandikci & Ekici, 2009)

and ideological incompatibility (Hegner et al. 2017).

Thus, stakeholders’ positive or negative response to a brand activism campaign often depends on how much the brand defends or violates social norms accepted by its audience, and whether it addresses topics relevant to their own life experiences (Baek et al., 2017). In this way, it is important for brands to understand the perspective and expectations of all stakeholders in relation to the cause they are supporting, to better predict their reaction and be prepared for it (Martins & Baptista, 2020), as well as to understand how it can affect the company-stakeholders relationship (Korschun, 2021).

Based on this literature, one can assume that the political/economic/cultural/technological conjecture in which a brand operates, the brand industry type (progressive versus regressive), and the core values of its stakeholders (progressive versus regressive) constitute key factors that determine the effectiveness of brand activism.

3.2 Internal predictors of brand activism effectiveness

From an internal management perspective, there are also some predictors that affect the success of brand activism actions. One of them is the congruence of the brand’s identity and values, its business practices and purpose with the defended cause - the so-called brand-cause fit (Becker-Olsen et al., 2006). This relationship can be ensured either through its positioning and image (Varadarajan & Menon, 1988), product line (Abitbol, 2019), or target audience (Champlin et al., 2019). Furthermore, the fact that the brand has historically been related to the defense of social issues also contributes to the perceived brand-cause fit (Cammarota & Marino, 2021).

In this way, although there are several authors who argue that brand-cause fit is insignificant for the success of activist campaigns (e.g., Das et al., 2020), or that a certain degree of incongruity between the brand and the cause can instigate more intense favorable responses, as long as the actions are perceived as authentic and altruistically motivated (e.g., Korschun, 2021; Vredenburg et al., 2020), brand activism-related literature (e.g., CSR, cause-related marketing, corporate philanthropy) has extensively documented that brands choose causes with which they have a high degree of fit, because this adjustment is also expected by stakeholders (Nan & Heo, 2007; Trimble & Rifon, 2006). Likewise, within the brand activism literature, Shetty et al. (2019) also found that, for a brand’s position on a socio-political issue to be successful, companies need to align their stance and the defended issue with their core values. The lack of this adjustment can even lead to a more critical attitude of stakeholders towards the brand/company (Nan & Heo, 2007), creating a feeling of distrust (Trimble & Rifon, 2006), as well as to skepticism towards the brand, as there is an inconsistency between prior expectations and new information (Becker-Olsen et al., 2006).

However, even when there is an adequate brand-cause fit, brand activism can be ineffective if consumers see those actions as insincere (Becker-Olsen et al., 2006). On the other hand, as mentioned above, brand activism actions with a moderate degree of incongruence with the brand’s values can still arouse very positive reactions, such as delight, if they are considered authentic initiatives (Vredenburg et al., 2020). For this reason, the construct of “authenticity” becomes crucial in brand activism and a necessary condition to achieve successful forms of activism, which must involve intangible (messages) and tangible (practical actions) commitments with a socio-political cause (Vredenburg et al., 2020).

The concept of brand authenticity has been described in the literature by several authors who associate the construction of the concept with factors such as the history of a brand, its origin, its manufacturing methods, brand credibility, as well as moral issues (Bruhn et al., 2012; Morhart et al., 2015). In the context of brand activism, Mirzaei et al. (2022) identified six dimensions for authenticity: social context independency (independent campaigns from topical and trendy social issues), inclusion (neutral messages in terms of gender, race, age, political matters, etc.), sacrifice (the extent to which a brand is prepared to forgo profit to support the cause), practice (the extent to which brands act on what they preach), fit (brand-cause fit), and motivation (perception about the brand’s intentions to defend the cause - profit-seeking and self-centred versus other-centred and genuine). In this way, to be considered authentic in activism, brands must maintain a continuous alignment between declared intentions and implemented actions, realizing how they can address the social issue in a genuine and complete way, before claiming the issue as part of their positioning strategy (Champlin et al., 2019).

Thus, Authentic Brand Activism is defined by Vredenburg et al. (2020) as the alignment of a brand’s activism messages in the traditional and digital media with prosocial corporate practices, assuming an explicit prosocial purpose and values. Sarkar and Kotler (2018) consider this alignment as a change in the management and marketing of organizations, in which companies abandon good intentions to start to act, either by establishing partnerships with NGOs whose purposes facilitate social change, including diversity of races and ethnicities in advertising campaigns, promoting the recruitment of minorities, or developing programs to combat inequalities (Wright, 2020). For the notion of authenticity in activism, it is also relevant to exist a personal conviction on the part of CEOs about the social topics covered. In this way, there will be consistency in the approach to social topics over time and coherence with these social motivations in all company practices and decisions, thus more easily involving employees and other stakeholders in the defence of the cause (Chatterji & Toffel, 2019). In contrast, when there is no coherence between brand activist messages in the media and their practical actions, when brands do not carry out substantive pro-social corporate practices or when they actively hide the absence of these practices, one can say that brands incur in an inauthentic form of brand activism, the so-called woke washing (Sobande, 2019). The term “woke” is of African American origin and a synonym for social awareness, so woke washing can be defined as brands that have an obscure or indeterminate conduct with respect to social practices (Vredenburg et al., 2020), but that adopt a strong communication regarding socio-political issues (Sobande, 2019), often without knowing and understanding it properly (Chatterji & Toffel, 2019). Frequently, these brands only engage in socio-political movements due to the pressure or urgency in responding to market expectations, ending up disconnecting their communications from their true purpose, values and corporate practices (Campbell, 2007), which gives rise to an opportunistic involvement that can result in the perception of brand activism as false, inauthentic or even misleading (Vredenburg et al., 2020).

Thus, one should expect that a brand activism strategy with a high brand-cause fit and/or a high degree of authenticity (Authentic Brand Activism) will be more likely to be effective than an activist strategy with a low fit between the brand and the cause and/or a low degree of authenticity (woke washing).

3.3 Potential positive effects of brand activism

Given the great expectation on the part of all stakeholders for brands to assume greater social responsibility and the potential of brand activism to fostering “win-win-win” situations for companies, stakeholders, and society, it would be expected that the number of firms taking an active position on social issues would increasingly grow (Hodgson & Brooks, 2007) and that the feedback from the public would be mostly positive (Eyada, 2020; Shetty et al., 2019). In fact, several studies demonstrated the impact of effective brand activism on brand support (Cammarota & Marino, 2021; Joo et al., 2019), brand reputation (Vredenburg et al., 2020), sales volume (Martinez, 2018) and even on market value (Linnane, 2018). Other positive effect that come from brands engaging with activist causes include increased exposure by third party blogs and influencers (Eyada, 2020), greater purchase intention and customer loyalty (Chatterji & Toffel, 2019; Corcoran et al., 2016), greater consumer willingness to pay a higher price (Shetty et al., 2019), higher engagement on social media (Gray, 2019), consumer gratitude, admiration and advocacy towards the brand (Joo et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2020), a larger hiring pool due to the increased awareness of values (Eyada, 2020), increased firm’s value (Vrangen & Rusten, 2019) and greater brand image (Abdallah et al., 2018). As previous research has shown, when the effectiveness of brand activism strategies is high, these actions can lead to multiple positive effects, such as increased brand support and brand reputation, greater brand image, higher sales volume, higher market and firm’s value, increased online exposure, higher engagement on social media, greater purchase intention, customer loyalty, greater consumer willingness to pay a higher price, consumer gratitude, admiration, and advocacy, and a larger hiring pool.

3.4 Potential negative effects of brand activism

Despite its potential positive effects, brand activism can also be misperceived by stakeholders, being still considered a risky strategy for brands (Eilert & Cherup, 2020). Brand activism concerns controversial or polarizing causes or events, where the public opinion is disparate, so taking a stand about them means taking risks that many brands are not ready to carry (Cammarota & Marino, 2021; Moorman, 2020). In fact, by choosing to address social issues, the company’s positioning on these topics become part of the brand’s identity, which can have positive but also negative effects for the brand, since companies are likely to deal with stakeholder discontent if they don’t agree with the company’s opinion or feel offended by it (Barros, 2019). This can lead several companies to choose not to defend any socio-political cause, for fear of the negative effects that this may have on the company’s ability to attract and retain customers or partners (Moorman, 2020).

Likewise, as brands engage in activist movements, the reasons driving these actions are increasingly scrutinized, which in some cases can lead to negative reactions from stakeholders (especially consumers), such as backlashes or boycotts, if they consider the brand’s activist actions as a mere marketing strategy or a way to increase products/services sales and generate profits (Eyada, 2020). This can, in turn, result in a decrease in sales, cash flow and stock prices (Farah & Newman, 2009), may affect brand reputation (Klein et al., 2004), lead to anti-brand behaviors and activism (Cammarota & Marino, 2021; Hollenbeck & Zinkhan, 2006) and cause a decrease in consumer’s purchase intentions (Klein et al., 2003).

Research thus suggests that, when the effectiveness of brand activism is low, this strategy can have some negative effects, such as stakeholder discontent, decreased brand reputation, decreased ability to attract and retain customers or partners, backlashes and boycotts, decreased sales, cash flow and stock prices, anti-brand behaviors and activism, and decreased consumer purchase intent.

4. Conclusion and guidelines for future research

The study of brand activism is still a recent field in strategic communication, and it is still very focused on the definition of the concept and its outcomes. Nevertheless, the factors behind the success or failure of brand activism actions were still little explored, and a compilation of the predictors and effects of this strategy is needed so that they can be empirically tested.

The purpose of this article was precisely to debate what can help or hinder brands to initiate and be successful in their activism campaigns, in addition to referring important effects that these actions may have. In this sense, a theoretical model of the effectiveness of brand activism was developed, highlighting the predictors that contribute to the effectiveness of brand activism, and its potential positive and negative effects. Specifically, this working model denotes that the political, economic, cultural, and technological conjecture in which the brand operates, the brand industry, the core values of its stakeholders, the ability to establish a good fit between the brand and the supported cause, and the authenticity demonstrated by the brand in the defence of the cause can determine the success of a brand’s activism actions, also influencing the outcomes of this strategy. The potential effects of brand activism, both positive and negative, were also drawn from an extensive literature review and may be hypothetically related to any predictors of the effectiveness of brand activism.

The introduction of a working model that compiles and relates causes and effects of the effectiveness of brand activism allows not only testing the relationships established between the variables, but also a better understanding of the current challenges of brand activism and how brands can overcome them to create a successful activist strategy.

On the one hand, it is considered that, to achieve positive results with their activist actions, brands must act in a democratic political, economic, cultural, and technological environment, conducive to activist actions, being able to use all possible means to address social causes and support activist movements and engaging in online and offline communication campaigns, in order to reach a wider audience and really contribute to the debate and resolution/improvement of the addressed issues. Brands should also understand which topics should or should not be covered considering its type of industry, as well as the social needs of their stakeholders and how they look at the social problems the brand intends to claim. This can be done through social listening practices, in order to address these topics in a way that the public understands and accepts. On the other hand, and to achieve effectiveness, brands must ensure consistency between their identity, values and purposes and the defended cause or, at least, that they address the issue in an authentic way, with the sincere responsibility to contribute to the cause. This may involve the creation of public-private partnerships to establish positive social changes or the implementation of internal practices that promote the defended position, promoting real social change. It is only by gaining a perception of authenticity on the part of all stakeholders that companies can acquire legitimacy in their activism efforts, which can be achieved, for example, by ensuring that brand activism practices are verified and attested by third-party certifications, adopting specific marketing metrics to monitor the results of these actions.

In an effort to characterize what underlies the effectiveness of brand activism and its possible outcomes, the proposed theoretical model establishes key directions for future research, namely by empirical testing the effect of external and internal predictors on the propensity for brands to engage in activism and the success of their activist actions, namely regarding the positive or negative generated effects. This can be done, for example, through comparative case studies, with brands operating in different geographic and technological contexts, from diverse industries and with different stakeholders and activism strategies. In addition, the model may also be refined in the future, through the introduction of variables that moderate and/or mediate the effect of predictors on outcomes, as the brand’s previous reputation, as well as through the study of new predictors (e.g., adopted communication strategies) or outcomes (e.g., promotion of prosocial attitudes of stakeholders).