INTRODUCTION

Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most common cause of physical impairment among children (1). It can be defined as a group of permanent and unalterable disorders of movement and posture due to non-progressive disturbances during the development of the central nervous system (CNS). These problems are accompanied by disturbances of sensation, perception, cognition, behavior and communication, as well as epilepsy and other secondary musculoskeletal problems (2). CP occurs in about 2 to 3 per 1000 live births (1) and its risk is higher among males (3). CP has a multifactorial etiology, and its risk factors are grouped into prenatal (responsible for most CP cases), perinatal and postnatal (4, 5).

Feeding difficulties are very common in CP, and their severity is related to the magnitude of brain injury (6, 7). Dysphagia, which refers to the difficulty in swallowing a liquid [oropharyngeal dysphagia (OPD)] or solid bolus (esophageal dysphagia) on the normal course from the mouth to the stomach (8), is one of the most frequent in CP. It is due to an injury in the area of the brain responsible for controlling the muscles in the oropharynx and esophagus and whose coordination is fundamental in the normal process of swallowing (6). OPD is the most common type of dysphagia in CP (6): it affects about 43% of children with CP (9), and both its prevalence and severity increase with age (10). Its clinical manifestations are very diverse, ranging from coughing to nasal regurgitation and alterations of voice quality, among others (11). In addition to the increased time to finish meals, associated stress and dehydration, individuals have an increased risk of food aspiration, which can lead to recurrent pulmonary infections, pneumonia and, in more severe cases, malnutrition and even death (6).

An early detection of dysphagia is important, given the severity of its consequences on the health and quality of life of individuals. The initial evaluation of on OPD consists on anamnesis and physical examination, which may be complemented with further exams such as endoscopy or videofluoroscopy (12, 13). Despite videofluoroscopy is considered the reference method in the diagnosis of dysphagia (13 - 15) it requires trained personnel, specific equipment, among other conditions, and therefore is difficult to be used in all individuals (16), which may lead to underdiagnosis, especially in early stages.

Some scales based on signs and symptoms of dysphagia may be useful for screening this condition; however, they need to be adjusted and validated prior to their use in a specific population or group (12). The Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10) is an example of such a scale and has several advantages: it was developed with the purpose of being an easy-to-use tool, quickly administered and able to assess the severity of symptoms, quality of life and treatment efficacy, regardless of the type of dysphagia (17, 18). In addition, this tool is also useful to assess clinical responses to treatment (17, 18).

The EAT-10 is composed by ten items, which comprise emotional (three items) physical (four items) and functional characteristics (three items) (18). For each item, the degree of difficulty in swallowing is measured in a scale ranging from 0 (“no problem”) to 4 (“severe problem”). The total score is obtained by the sum of the scores of all items and can vary between 0 and 40. A total score equal to or higher than 3 indicates an anomaly in swallowing (17). Both the original (17) and the Portuguese (19) version of the EAT-10 present good psychometric properties. However, for the Portuguese version these were studied only for patients aged 40 years or above and mostly with dysphagia following stoke or dementia (19). Moreover, we are not aware that this or other scale is validated and adapted for the evaluation of dysphagia in the Portuguese population with CP.

OBJECTIVES

This research aims to study the psychometric characteristics of the EAT-10 in a sample of Portuguese individuals with CP aged between 11 and 61 years and, based on this, to adapt this tool to be used in CP patients.

METHODOLOGY

Ethical Procedures

The study was carried out in accordance with all ethical requirements stated by the Helsinki Declaration and by applicable legislation, and was approved by the Direction of the Associação do Porto de Paralisia Cerebral, which is responsible for the ethical evaluation of reseach studies carried out in the Centro de Reabilitação da Associação do Porto de Paralisia Cerebral (CRAPPC). Potential participants were informed of the study’s main aims and procedures, and any doubts were clarified, after which written informed consent was obtained from the participant or their legal representative.

Study Design and Sample

This cross-sectional study used a convenience sample of 75 users of the CRAPPC aged between 11 and 61 years (10.7% aged from 11 to 17 years), considering as inclusion criteria having a clinical diagnosis of CP. In order to compare the results with a group with no increased risk of dysphagia, a control group was used, consisting of 75 caregivers of users and collaborators of the CRAPPC aged between 15 and 70 years; following the procedure used in the original scale’s validation study, the inclusion criteria for this group was the absence of past medical history of voice, swallowing, reflux, airway, neurologic, rheumatologic, hematologic or neoplastic disorders (17). The presence of any condition that could influence the ability to answer the scale or free and informed participation was considered as exclusion criteria for both groups. There were no refusals to participate or missing data in any of the groups.

Data Collection

Data collection took place from April to June 2017. All participants were approached in the facilities of the CRAPPC. The questionnaire was self-administred in a written format, unless in cases when there were difficulties in writing, and included information on sex, age, if the participant had ever performed tests to assess swallowing, and the Portuguese version of the EAT-10 (19).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with IBM® SPSS® Statistics, version for Windows®. Descriptive statistics consisted on absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies, or means and standard deviations (SD). Normality of cardinal variables was assessed using skewness and kurtosis. The internal consistency of the scale was measured using Cronbach´s alpha coefficient. The scale was submitted to factor analysis by principal component extraction method (without rotation). The factor analysis models were validated using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) sampling adequacy measure and Bartlett’s test. The scree plot method (20) was used to determine the number of components to be retained. Both internal consistency and factor analysis were performed only in the group with CP. Fisher's exact test was used to compare proportions (sex and percentage of participants scoring 0 on the scale) between groups. Student’s t-test was used to compare mean age and Mann-Whitney’s test to compare mean ranks of the scale’s total score between groups. The null hypothesis was rejected when the level of critical significance for its rejection (p) was below 0.05.

RESULTS

The proportion of males did not significantly differ between groups (CP: n = 45, 60.0%; control: n = 42, 56.0%; p = 0.741). Participants with CP were significantly younger than those in the control group (mean age= 30 years, SD = 10 vs. 36 years, SD = 13; p = 0.004). All participants from both groups reported never having done any evaluation of their swallowing process. The answer “no problem” was the most prevalent for all items in both groups. Among participants with CP this proportion varied from 77.3% (item 9) to 98.7% (item 7). As for the control group, scores different from 0 were found only for items 1 (1.3%), 5 (5.3%), 9 (2.7%) and 10 (1.3%).

Internal Consistency and Factor analysis

Table 1 shows the results of the internal consistency analysis. As item 1 presented a negative and very weak (|r| < 0.2) item-total correlation (25) we opted to exclude it, thus reducing the scale to nine items. The Cronbach's alpha (α = 0.749) reveals that the EAT-9 (version of the EAT-10 after the removal of item 1) has an adequate internal consistency.

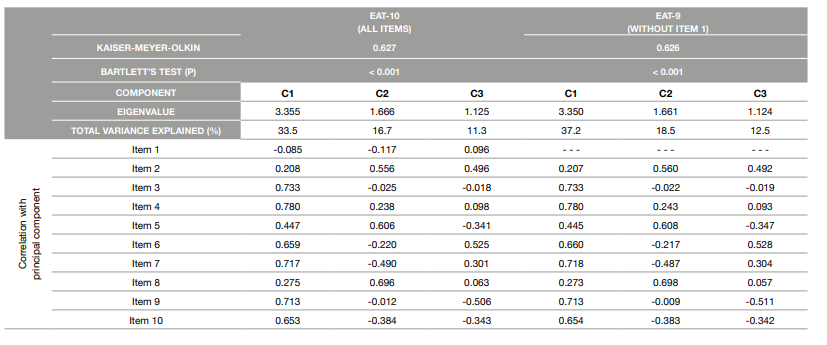

Table 2 presents the results of the factor analysis. Both the KMO and the Bartlett’s test indicate a good adequacy of the models. Despite the fact that the factor analysis generated three components with eigenvalues higher than 1, the scree plot analysis clearly suggested a unifactorial solution, with the latent factor explaining 37.2% of the total variance. In line with the results from the internal consistency analysis, the correlation of item 1 with this factor supports its exclusion.

Comparison Between Groups

Participants with CP scored higher on the EAT-9 than the control group (p <0.001). In the control group, 92.0% (n = 69) of the participants obtained a total of 0 on the scale, while in the group with CP this proportion was of 53.3% (n = 40). The maximum values obtained were of 5 in the control group, and 19 in the group with CP. In the group with CP, 28.0% (n = 21) of the participants had a score on the EAT-9 indicative of anomaly in swallowing (i.e., equal to or higher than 3, as in the original version), while in the control group only one participant (1.3%) presented such a score.

DISCUSSION OF RESULTS

This study investigated the psychometric characteristics of the EAT-10 among Portuguese individuals aged 11 to 61 years old with CP diagnosis, and resulted in an adapted version for use in this population (EAT-9). Despite the fact that the analysis led to the exclusion of one of the items that constituted the original scale, the EAT-9, adapted version for the Portuguese population with CP, maintained a unifatorial structure. As described in previous studies, this scale was easily and rapidly answered (about 2 minutes) and its total score was easily calculated (12, 16, 17). Overall, the EAT-9 showed adequate psychometric properties for the Portuguese population with CP.

The results of translation and/or validation studies of the EAT-10 in several countries showed a good internal consistency of the scale (α > 0.8) (17 - 19, 22 - 25). In the current study, despite the Cronbach's alpha value for the EAT-9 version (α = 0.749) was lower that those reported in previous studies, it still reveals an adequate internal consistency of the scale. As mentioned, other translation and validation studies of the EAT-10 were previously carried out in Portuguese samples. In one of these studies, developed among individuals with dysphagia due mostly to stroke, the Cronbach's alpha was 0.75 (12), a very similar value to that obtained in our study.

The validation study of the EAT-10 for the Portuguese population (from which the EAT-10 version used in this research was obtained) was developed in a sample of 315 participants with symptoms of dysphagia (most of them caused by stroke and head and neck cancer) and 205 controls (19). The Cronbach's alpha reported in that study was very high (α = 0.95) and no item was excluded. This may indicate the usefulness of studying the psychometric characteristics of this scale in subgroups of the population with specific conditions that may predispose individuals to a higher risk of some dysphagia symptoms, such as the population with CP, independently of the existence of studies based on samples with a great variety of problems that can cause or trigger disturbances in swallowing. Moreover, this scale has been understudied among children and adolescents. Despite the existence of a pediatric version (which will be more suitable for younger age groups), while it is not available for individuals with CP the EAT-9 may provide an adequate way to minimize the lack of a more specific scale.

Weight loss is frequent in the population with CP, and may be due to difficulties in chewing, frequent vomiting, difficulties in swallowing, lack of oro-motor control, absence of sucking reflex (26), hypertonia with incorrect body posture or hypotonia, high energy expenditure due to a state of muscular tone (27), among others. Given this great diversity of causes, it is possible that swallowing problems are not perceived as responsible for weight loss, which may explain the results leading to the exclusion of item 1 (“My swallowing problem has caused me to lose weight”) from the scale. Despite the exclusion of one item from the original scale, we consider that, before further research is done, for both clinical and research purposes a total score equal to or higher than 3 should continue to be used as indicating an anomaly in swallowing. As expected, participants in the control group presented lower total scores in the EAT-9 than those with CP. While only one participant in the control group presented a total score equal to or higher than 3, in the CP group more than a quarter of the participants had score indicating anomalies in the swallowing process. These results are in line with the literature reporting a higher proportion of individuals with swallowing problems among the population with CP (9,28). Moreover, it is worth noticing that all participants reported never having performed any tests to assess their swallowing process, which may indicate an underdiagnosis of dysphagia among the population. This probable underdiagnosis reinforces the need to use screening tools to identify of individuals with symptoms of dysphagia, so that they are referred to more detailed evaluations and subsequent treatment, thus avoiding or reducing complications.

In Portugal few health units have specialized methods for confirming dysphagia, such as videofluoroscopy of swallowing (29). When it is not possible to perform such tests, tools such as the EAT-10 (or the EAT-9) can be a solution. When adapted and validated for use among specific populations, this scale may be used as a first-line screening tool in the detection of problems of swallowing, dysphagia or individuals predisposed to nutritional and pulmonar complications that need to be referred for a more exhaustive and accurate evaluation (1, 16, 30).

Although the EAT-9 can be used among the Portuguese population with CP, many individuals are not able to answer the scale, which is a limiting factor of this tool in the evaluation of the risk and/or presence of swallowing problems. Nevertheless, a pediatric version of the EAT-10, answered by caregivers, has already been developed, and showed adequate psychometric characteristics (31). Thus, the adaptation of this scale for Portuguese individuals with CP and their caregivers may be an alternative to overcome this problem.

Limitations and Strenghts

A potential limitation should be considered when interpreting the results. We found significant differences in age between the two groups. However, we consider that the magnitude of this difference was possibly not enough to have a major impact on the results comparing the two groups.

Besides the fact that, to our best knowledge, this is the first research adapting the EAT-10 to be used among Portuguese individuals with CP, other strengths should be highlighted. Compared with most studies within this population, the size of the sample used may be considered large. Moreover, the use of a control group made possible to compare individuals with CP and participants with no specific condition or pathology associated to dysphagia.