INTRODUCTION

Food and nutrition labelling in prepacked foods is a source of information to the consumer in terms of food safety and nutrition (1, 2). The food product label conveys a set of mandatory information that defines it, namely the name of food, the country of origin or place of provenance, the lot number, the net quantity, the name or business name and address of the food business operator, the ingredient list, the allergens information, the type, quality and quantity of the ingredients and categories of ingredients (QUID), the nutrition labelling, the date of minimum durability, special storage conditions and/or instructions for use, as compulsory (3 - 6). The nutrition or health claims, the front-of- pack nutrition labelling and others are non-mandatory information (3, 7, 8). In recent years, labelling has gained significant importance as an effective tool in protecting consumers’ health, since it has information that, when properly used, can lead to conscious and healthy food choices (9). The influence of food environments as a collective physical, economic, political, and socio-cultural context can influence individuals' consumption choices and nutritional status, leading to a healthier diet and general well-being through food labelling (4, 10, 11). Consequently, it must be a requirement to create food labels that are clear and can be trusted. Regarding this situation, the European Parliament and of the Council on the 25th of October 2011 implemented the Food Information to Consumers (FIC) - Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 (3, 12, 13). The focus of the existing guidelines has been changing, in order to safeguard the consumer’s well-being through transversal rules in the entire food system and its operators. Since the implementation of the FIC Regulation, food and nutrition labelling rules were harmonized and became necessary to study the possible simplification of the nutrition declaration. Therefore, a smaller risk of the prevalence of non-communicable diseases can be avoided by choosing energy- dense foods, sugar-sweetened drinks, processed and prepacked foods, encouraged by consumption trends and/or individual food choices (14 - 16). While the regulation was in the development stage, a series of investigations were occurring to understand how information can be used and interpreted (17). Labelling is an important tool for professionals in the food and nutrition area (12). However, the reading and usage of the label information may vary, according to the area of activity, professional backgrounds, interests, motivations, and individual knowledge. Nevertheless, there was a need to study the vision and position of the professionals in the food area regarding this matter. It is known that they can be direct or indirect intervenient in the food supply chain, directly in the food production process or in the consumption stage (with an underlining role as food educators, researchers, or regulators), or indirectly in both.

OBJECTIVES

This paper aimed to analyse the differences in food and nutrition professionals’ opinions and suggestions regarding nutrition labelling on prepacked foods, established by Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011.

METHODOLOGY

A cross-sectional study was conducted, using an observational design (18, 19). Study population: The target population were Portuguese professionals in the food and nutrition area. The recruitment strategy for the participation of the professionals was through contacting several Portuguese entities in the food and nutrition area (N=45), namely policy decision-makers and regulatory entities (governmental and non-governmental organizations) of food-related area (N=7); public health associations in the food and nutrition area (N=5); food business associations/ entities (N=3), higher education institutions with bachelor's, post-graduate, master’s, and doctoral degrees in the food area (N=18), scientific journals or other communication channels (N=5); and, certification entities (N=7)). Sampling: A non-probabilistic and convenience sampling was applied to recruit Portuguese food and nutrition professionals. This method was chosen to cover as many professionals as possible and considering that not all professionals had an equal participation opportunity. Moreover, to avoid multiple responses by the same professional, a brief warning was given at the beginning of the survey: "In case of receiving this request through different organizations/ entities, please respond only once". The eligibility criteria required was being 18 years old and over, living and working in Portugal and having a professional activity in the food and nutrition area. Data collecting tool: An online self-administered survey was developed, using the software LimeSurvey® available at the Faculty of Nutrition and Food Sciences of the University of Porto. The survey, which was written in Portuguese, was organized into five sections and 24 questions (fourteen closed questions on a 5-points Likert type scale, six multiple-choice and four open-ended questions). This was developed after reviewing the relevant literature used in previous studies related to general food labelling and included the new food labelling rules (3). The five sections included: 1) Section A - The general perspective of the food professionals regarding labelling; 2) Section B - The new regulation: content, presentation, and legibility; 3) Section C - Mandatory “back-of-pack” nutrition labelling: comparisons of the main changes; 4) Section D - Future uses of “front-of-pack” nutrition labelling: additional forms of expression and presentation of the nutrition declaration; and 5) Section E - Participants’ sociodemographic characteristics. The average survey completion time was twelve to fifteen minutes. It was available from December 2016 to April 2017. Participants: Using the institutional or professional contact, the food and nutrition Portuguese entities were contacted to assist in the dissemination of the study through its members, clarifying the study’s setting (study objective, an academical focused investigation, target population, safeguard of the collected information and the anonymity of the participants) and appealing to their participation (via email with the survey link). Participants were instructed to give their professional opinion according to their area of activity. Evaluated data: Firstly, a general analysis of the survey answers was conducted. Secondly, for this paper, two questions were analysed in deep, namely, the question “As a food professional, do you consider that changes in the presentation and content of the nutrition information provide an accessible and clear reading/understanding for the consumer?” (a 5-points agreement Likert type scale) and the open-ended question “If you do not agree, what would you change?". The professionals’ suggestions given by the open-ended question regarding nutrition labelling on prepacked food were analysed and categorized by subject. Lastly, a comparison between the group of professionals who make suggestions and those who did not, regarding the survey’s answers was done. Statistical data analysis: Different methods and statistical tests were performed, using IBM SPSS® Statistics version 24 software. Statistical significance was set at 0.05. A descriptive statistical analysis was carried out. Differences between groups were assessed using the Mann-Whitney U test and the chi-square test.

RESULTS

The sample (N=297) of Portuguese professionals who participated in the study included women (81.1%), married (53.2%), with an average age of 39 years (SD=12.1), between 18 and 75 years old, with higher education (99.9%) and 46.0% from the “Food and Nutrition Sciences” course.

Evaluation of the Professionals’ Opinion Regarding Accessibility and Clarity of Nutrition Labelling for the Consumer

Out of a total of 297 participants, 10.1% (N=30) strongly disagreed or disagreed that the nutrition labelling changes would favour a better reading and understanding by the consumers, and 11.1% (N=33) replied to the open-ended question, with suggestions for improvements in nutrition labelling.

Analysis of the Suggestions Provided in the Open-ended Question to Improve Nutrition Labelling

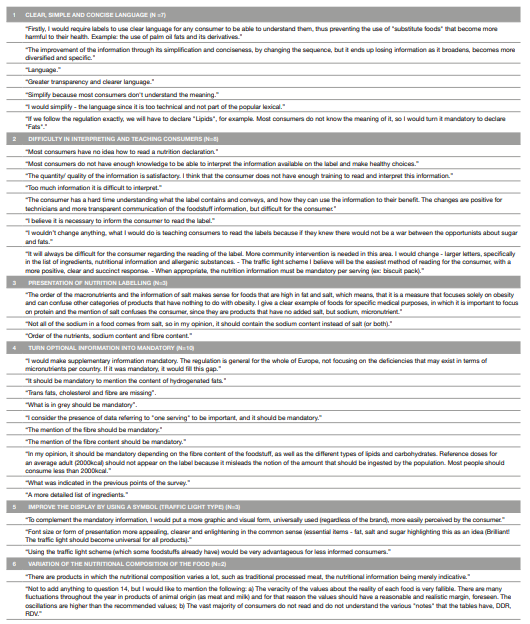

The given answers (N=33) were grouped by subject (Table 1): 1) Clear, simple and concise language (N=7), 2) Difficulty in interpreting and teaching consumers (N=8), 3) Presentation of nutrition labelling (N=3), 4) Turn mandatory the optional information (N=10), 5) Improve the display using a nutrition symbol (traffic light type) (N=3), and lastly, 6) Variation of the nutritional composition of the food (N=2).

Comparison Between the Professionals Who Gave Suggestions and Those Who Did Not

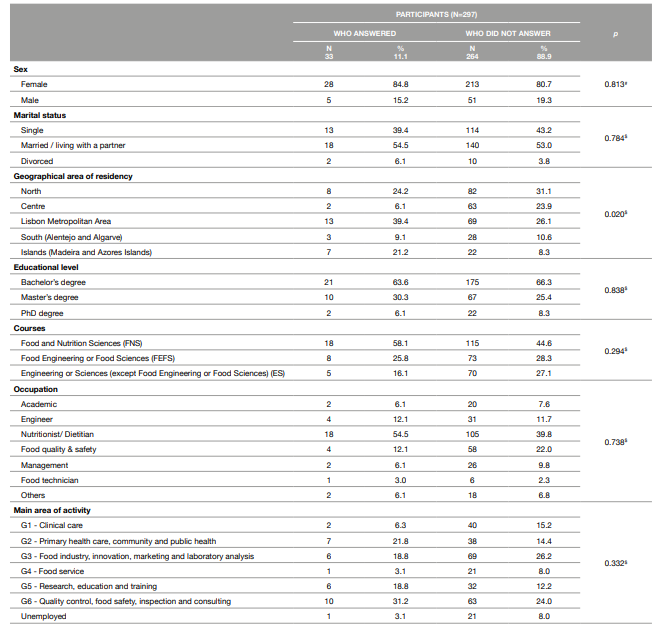

A comparison of the sociodemographic characteristics between the professionals who answered versus those who did not answer the open-ended question was carried out. Significant differences were not found (Table 2), except for the geographical area of residency, verifying that the probability of those who made suggestions is greater in the Lisbon metropolitan area and Islands.

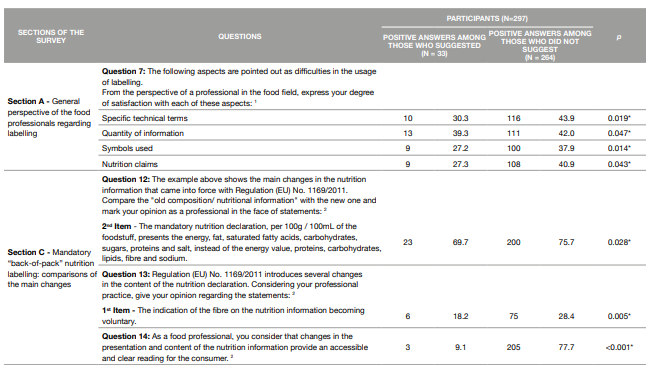

The significant differences between groups of professionals who made suggestions (N=33, 11.1%) and those who did not (N=264, 88.9%) are presented in Table 3 (non-significant results were omitted for brevity). A comparative analysis of the positive survey answers (by positive it entails only the levels of agreement 4 and 5 in the Likert scale) between both professional groups was performed.

Those who made suggestions were less satisfied with the current information on the label, namely the specific technical terms (p=0.019), the quantity of information (p=0.047), the symbols used (p=0.014), and the nutritional claims (p=0.043). They agreed less with the changes in the presentation order of the mandatory “back-of- pack” nutrition labelling (p=0.028), as well as the fibre content being voluntary (p=0.005). Furthermore, only a minority of those who made suggestions believed that adjustments in the presentation and content of the nutrition labelling provided a more accessible and clear reading to the consumer (9.1%) (p<0.001).

Table 2: Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants who answered versus those who did not answer the open-ended question

*Analyse Descriptive Statistics-Crosstabs $(X2) Pearson or # Fisher's Exact Test

Table 3: A comparative analysis of the positive survey answers between those professionals’ who suggested and those who did not suggest in the open-ended question

*Analyse Descriptive Statistics - Mann-Whitney Test.

1The values presented correspond to the sum of all positive answers namely "satisfied" and "highly satisfied".

2The values presented correspond to the sum of all positive answers namely "agree" and "strongly agree".

DISCUSSION OF RESULTS

The professionals’ suggestions given by the open-ended question regarding nutrition labelling on prepacked food were analysed, resulting in six categories which were grouped by subject. From these categories, two sets of suggestions were proposed. The first one was to simplify the information of the nutrition labelling, in order to promote the reading and usage by the consumers with low nutritional literacy (subject 1, 2 and 5). These professionals suggested that it is necessary to turn the language into a clearer, simpler, and more concise one as presented “would simplify the language” (subject 1) and improve the display by using a symbol as cited “The traffic light should become universal for all products” (subject 5) since the current form of presentation is difficult to interpret (subject 2). This information has to be explained to the consumer “to inform the consumer to read the label” (subject 2) or the consumer should be instructed on how to read, interpret and use the information available “I would do is teaching consumers to read the labels” (subject 2). Both suggested actions focus on the consumer’s education and its empowerment regarding the use of food and nutrition labelling, as it had already been mentioned (1, 12, 20). The difficulties on label usage have been previously reported, mainly in studies with consumers (21 - 24). While the EU regulation harmonizes food labelling rules, it is necessary to improve the reading, usage and understanding of the available information to the consumer. Given the complexity of the information and the low nutritional literacy, the most favourable option becomes a symbol on the front-of-pack, as a means of simplifying nutritional information and leading conscious food choices (25, 26).

The second improvement included the need to promote the accuracy and the usefulness of the nutrition labelling as it is currently presented (subject 3, 4 and 6). In this case, it was advocated the adjustment of the presentation of the nutrition labelling (subject 3), to turn optional

information into mandatory (subject 4), and to consider the variation of the nutritional composition of the food (subject 6). All these suggestions tend to propose more detailed information related to the nutritional presentation as mentioned “it should be mandatory depending on the fibre content of the foodstuff, as well as the different types of lipids and carbohydrates” in subject 4 and “Order of the nutrients, sodium content and fibre content” in subject 3). The aspects listed (what to present in the nutrition declaration, optional and/or mandatory presence of certain nutrients, forms of presentation, the indication of the portion, DDR) lead to the discussion of issues such as the type, content, and presentation of the information that appears on the label. Since December 2014, the implementation of the mandatory nutritional information by the FIC regulation showed that there is no relevant data that allows the evaluation of the usefulness and relevance of it in the back-of-pack (25, 27). The previous studies before the implementation of the regulation raised a series of needs, expectations and uses regarding the information available to the consumers (28 - 30). It was assumed that having unanimous information would be difficult, but the commitment would be to simply the information considered most important on a first phase. In the second phase, the public health goal was the priority, it aimed to provide accurate and easy-to-understand front-of-pack nutrition information (26, 31). The analysis of the mandatory information on labelling became a secondary matter (25). In this study, a relevant concern was “the nutritional composition varies a lot, such as traditional processed meat …” and “The veracity of the values about the reality of each food is very fallible. There are many fluctuations throughout the year in products of animal origin (as meat and milk) and for that reason the values should have a reasonable and realistic margin, foreseen.”, demonstrating a need to consider the nutritional variation of the food composition.

Regarding the differences between the group of food and nutrition professionals who made suggestions and those who did not, it was found that those who gave suggestions were less satisfied with the current information on the label, namely the specific technical terms, the quantity of information, the used symbols, and the nutritional claims. Comparably, this group of professionals showed less agreement with the changes implemented by Regulation (EU) No. 1169/ 2011, such as the presentation order of the mandatory nutrition information and the optional indication of the fibre content. They also presented less agreement with the alterations in the presentation and in the content of the back-of-pack nutrition labelling, which may provide a more accessible and enlightening reading for the consumer. Some professionals are not still that satisfied with its presentation because it may provide too much detail for the consumers (the specific technical terms, the quantity of information, the used symbols, and the nutritional claims), possibly because they may have low nutrition literacy.

This study had several methodological considerations.

In the study design, the collection of data resulted in a convenience sample, thus non-probabilistic. Since the total number of professionals working in the food and nutrition area in Portugal is unknown and there is no practical way to contact them, it is not possible to guarantee that all professionals were reached. Nevertheless, the main entities in this area were contacted to reach the largest possible number of professionals. The choice of entities in the food and nutrition area was done by researching the ones that would be relevant and representative of the sector, authorities, and food’ associations, which could reach a larger spectrum of professionals.

Limitations regarding the data collection procedure were related to using an online self-administered survey since the comprehension errors could not be clarified. This might constitute an accessibility limitation for some professionals, on one hand, but on the other hand, as an advantage, an online procedure allowed the collection of a larger sample from different geographic locations of the country quickly and conveniently (1, 32). Concerning the nature of the sampling, it is important to consider the possible bias associated with the results obtained, since the opinion/ suggestions may have been given by a minority "interested" on this topic, which chose to respond to the survey and presented an answer to the open question.

Even though the mentioned limitations, some strong points should also be considered as the web-based surveys became a common and reliable method for information gathering and the target population (food and nutrition professionals), who has not been the focal point of many investigations on food consumption and nutrition. These professionals can bring relevant health-related and political inputs, as users of the food and nutrition labelling information.

CONCLUSIONS

This analysis contributed to the understanding of the professionals' concerns regarding the changes in food and nutrition labelling scope since they have the ability to see and perceive food and nutrition labelling as an important tool as users, as to be used by the consumer.

According to the suggestions of the food and nutrition professionals about the presentation and content of the nutrition information established by Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011, two sets of suggestions were proposed. The simplification of the nutrition labelling information and the promotion of the accuracy and the usefulness of the nutrition labelling as it is currently presented, provide more perceptible and useful information to the consumer. The development of nutrition labelling educational tools, as a way of promoting consumer’s empowerment, which ultimately leads to healthier food choices and improves nutrition literacy.