INTRODUCTION

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by synovial inflammation with production of autoantibodies, malformation and destruction of several joints, cartilage and bone (1, 2). Pain, swelling, stiffness and reduced function in peripheral joints are the most common symptoms, and the main responsible for compromising the quality of life of these patients (2, 3).

RA is one of the most common autoimmune diseases and its prevalence varies by geographic region (3, 4). The prevalence of RA is higher in Western countries, particularly in North America and Europe where RA affects about 0.5% to 1% of people, with variation among different populations (2-4). In Portugal, the prevalence ranges between 0.8% to 1.5%, being more common in women, especially post-menopausal women (5).

Genetic and environmental factors are considered the main causes for development of RA (4). Environmental factors such as smoking, air pollution, diet and viral infections contribute to the development of systemic autoimmunity (4). The association of these factors with genetic predisposition increases the risk of RA (4).

Eating habits can represent both a risk factor and a protective factor for RA (4). The Western diet is associated with an increased risk of RA, since this dietary pattern is characterized by high intake of refined carbohydrates, red meat, trans and saturated fats, and by a low proportion of omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acids, which may increase the inflammatory condition (4). The influence of diet on the development of RA has been widely studied because specific foods can induce pro- inflammatory effects while other may have anti-inflammatory effects (4). In addition, diet also impacts the composition of gut microbiota. A diet rich in animal protein and saturated fat contributes to the increase of the bacterium Prevotella copri spp in the gut microbiota, which is related to the development of RA, once this bacterium induces pro-inflammatory cytokines and increases intestinal permeability (6). Therefore, high levels of this bacterium in the early stages of RA may be an important mechanism linking dysbiosis to the pathogenesis of RA (4, 6, 7).

The most used strategies in the management of RA are based on pharmacological therapy, with the use of immunosuppressants that aim to prevent or reduce symptoms (2). However, in several cases there is no improvement, with persistent disabling symptoms, such as pain and fatigue (2). Besides, although pharmacological treatment has improved substantially in the recent decades, there is no cure for RA and the most of patients need pharmacological treatment throughout their lives (3). Furthermore, the drugs used are frequently associated with significant side effects, such as insulin resistance and weight gain, which in turn increases the risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and general morbidity (8).

RA has been shown to be associated with an impairment of nutritional status with multifactorial etiology (9). In addition to the classical symptoms that characterize RA, the disease has also been associated with gastrointestinal disorders, including early satiety, mucosal ulcers, dyspepsia, nausea, diarrhea, and constipation. In the most severe cases of RA, there is also an increased risk of nutritional deficiencies, especially folic acid, vitamin D, zinc, retinol-binding protein and thyroxine-binding prealbumin, frequently caused by higher disease activity and glucocorticoid therapy (10). Glucocorticoid therapy affects the digestion and absorption of nutrients and can also lead to intestinal problems, such as acid reflux, ulcers and even kidney failure (10, 11). The clinical condition of RA patients, particularly at an advanced stage, may lead to the development of malnutrition, and in most severe cases to rheumatoid cachexia (11).

Malnutrition has been shown to reduce the quality of life of these patients, as well as increase the risk of morbidity, hospitalization and even mortality (11). In the case of hospitalized patients, one out of three RA patients can be at nutritional risk (11).

RA patients frequently associate the consumption of some foods with the worsening of symptoms (12). Therefore, they tend to eliminate those foods from their diet (12). Elimination diets are often implemented by these patients (12). Foods, such as meat, fish, eggs, cottage cheese, rice, beans, peas and chickpeas are often left out. In addition, the “nightshades”, i.e., foods that contain solanine, such as tomato, potato, eggplant and peppers are often eliminated from daily diet (12, 13). It is worth noticing that most of these dietary restrictions are empirical and not based on scientific evidence (12, 13). Moreover, these strategies may even lead to unbalanced dietary patterns (12).

Nutrition therapy has been studied as a form of additional treatment to pharmacological therapy (5).

The anti-inflammatory diet is based on the principles of Mediterranean Diet (MD), consisting of foods rich in antioxidants, namely polyphenols, carotenoids and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), of low glycemic index foods, and the use of extra virgin olive oil as the main source of fat (14). In addition, this diet promotes low consumption of foods rich in trans fat and saturated fat, sugary drinks, alcoholic beverages, red and processed meat (14). Among the nutrients that have demonstrated benefits as decrease of inflammation and relieve of symptoms are omega-3 PUFAs, monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), vitamins and minerals, and several phytochemicals (2, 5).

Beyond the anti-inflammatory diet concept, other dietary interventions have been studied as potentially beneficial in the treatment of RA, including the elimination or fasting diet, the vegetarian diet, the gluten free diet and the MD (8).

The aim of this literature review was to analyze the implementation, applicability, benefits, as well as limitations of the anti-inflammatory diet in RA.

METHODOLOGY

In order to collect information for this literature review, a literature search was carried out using the PubMed database, between the month of November 2021 and the month of August 2022. The search terms used were: “((inflammation AND diet*) OR anti-inflammatory diet) AND (arthritis, rheumatoid OR rheumatoid arthritis)”. Inclusion criteria were defined as publications from the last 10 years, studies conducted in adult humans about the effect of anti-inflammatory diet on RA, and were excluded from this review, studies in animals, research on nutritional supplementation and studies that included other types of pathologies. A total of 234 articles were found, of which 216 articles were excluded for non-compliance with the inclusion criteria.

Finally, 18 articles were selected. Through the bibliographic references of the selected articles, it was possible to obtain 9 more articles as a result of snowball research.

Anti-inflammatory Diet

The anti-inflammatory diet is based on the MD and as such consists in abundance of fruit, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, olive oil as the main source of fat, a moderate amount of fish, meat and dairy products and low consumption of red meat, processed foods, foods high in saturated fat, sugary drinks and alcohol (14, 15). This is reflected in a diet rich in some nutrients and bioactive compounds with anti- inflammatory properties and antioxidant effects, such as vitamin D, PUFAs, MUFAs, polyphenols, carotenoids and flavonoids (14-16).

The anti-inflammatory diet has been recently studied and has been associated with decreasing symptoms of RA, namely preventing sensitive and swollen joints, poor physical function, pain, weight loss and preventing high disease activity (2, 3, 14, 16-20). These positive effects are associated with the abundance of nutrients with antioxidant effects, which can have an impact on inflammatory processes and thereby mitigate symptoms (20). There is a reduction of oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokine levels, with increasing of short-chain fatty acid producing bacteria that has benefits the structure of the intestinal barrier (20).

In a single-blinded controlled crossover trial conducted by Vadell et al. (2020), participants aged 18-75 years, with disease duration ≥ 2 years, were randomly assigned to the intervention group (anti-inflammatory diet) and control group (control diet) (2). After a 4 month washout period, the diet was switched (2). The main foods composing the anti- inflammatory diet were fish, vegetables, potatoes, whole grains, fruit such as pomegranate and blueberries, and low-fat dairy products (2). During the study participants received weekly food items to prepare breakfast, one snack, and one main dish. In relation to the meals not provided, participants in the intervention group were instructed to limit meat intake to a maximum of three times a week, eat more than five servings of fruit and vegetables per day, particularly berries, and consume low-fat dairy products and whole grains (2). Both diets provided the same amount of energy and carbohydrates relative to fat. The intervention diet provided mainly unsaturated fat, while the control diet provided mainly saturated fat, in addition, the intervention diet provided lower amounts of protein in contrast to the control diet (2). Disease activity score calculator for rheumatoid arthritis (DAS28) was applied at the screening visit, and blood samples were collected before and after each period of the diet, for evaluation of erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein. After the intervention period, there was a significant reduction in the disease activity, a higher reduction than during the control period (2). There were no significant differences for tender and swollen joints (2). However, in this study 56% participants showed improvement in joint pain after the intervention period, compared to 39% of participants with improvement after the control period (2).

These results reinforced the positive effects of anti-inflammatory diet in patients with RA as a complementary therapy to pharmacological intervention (2).

According to results published by Hulander et al. (2021), patients with RA also showed a significant decrease in tumor necrosis factor ligand superfamily member 14 (TNFSF14), a protein that induces osteoclasts proliferation and promotes bone destruction in RA, after an anti- inflammatory diet intervention (3). Another aspect is fat mass loss in overweight or obese patients who implement the anti-inflammatory diet, which can reduce inflammation associated with adipose tissue (14, 18).

Wadell et al. (2021) reported that anti-inflammatory diet also improved the health-related quality of life (HrQoL) in 50 RA patients (17). In addition, these authors also found a significant improvement in physical functioning of patients after intervention with an anti-inflammatory diet (17).

Bustamante et al. (2020), through an observational study, found that applicability of the anti-inflammatory diet had high adherence among patients with RA (16).

Tedeschi et al. (2017) analyzed how foods affect RA symptoms through a prospective longitudinal study of 300 RA patients (19). The authors found that 24% individuals reported that at least one food item affected their symptoms (19). The most mentioned foods associated with the improvement of symptoms were blueberries, strawberries, fish and spinach (16, 19). Other foods, such as red meat, soft drinks, and sweet desserts seemed to negatively affect RA symptoms (16, 20). PUFAs are abundant in the anti-inflammatory diet and have been the most studied nutrients due to the anti-inflammatory properties (18). PUFAs also influence the functions of lymphocytes and monocytes, which regulate inflammatory pathways in chronic inflammatory diseases, such as RA, thus verifying a significant reduction of inflammatory biomarkers, such as IL-6 (20).

Regarding specifically the effect of PUFAs intake in RA, Giuseppe et al. (2013) conducted a prospective cohort study among a sample of 32,232 women during a mean 7,5 years follow-up period. This study results showed that a daily intake of PUFAs higher than 0,21g reduced the risk of developing RA by 35% (21).

Other results also report that PUFAs significantly reduce RA symptoms, namely morning stiffness (20, 22-24) .

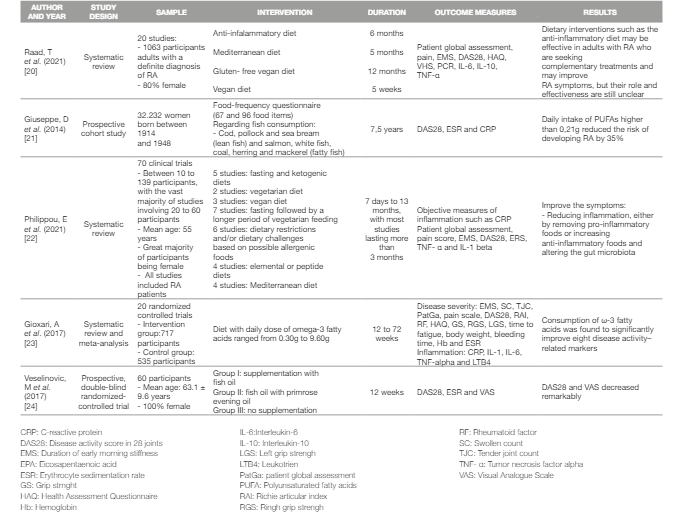

The results of the studies regarding the effect of PUFAs in RA are summarized in Table 1.

CRITICAL ANALYSIS

Studies have shown that dietary habits can act as an environmental trigger in genetically susceptible individuals, leading to the development of RA. However, dietary changes can also contribute to ameliorate symptoms (22).

Special attention should be paid to patients who make dietary changes autonomously and without scientific basis, since patients with RA have an impairment of nutritional status, particularly those in an advanced stage (17, 22, 25). In addition, eviction diets, which RA patients often do, without any follow-up or recommendation from a health professional, contribute to the development of unbalanced diets, thus increasing impairment nutritional status and clinical status (22).

The use of specific dietary patterns or isolated nutrient supplementation may have different effects, once in a dietary pattern several nutrients together in the food matrix may have more beneficial and potentiated effects in the body (25).

The association between diet, microbiota and gut permeability has been shown to be associated with the inflammatory response induced by intestinal dysbiosis, contributing to the development of rheumatic diseases (6, 22, 26, 27). Diet can directly affect the immune response, stimulating or inhibiting inflammatory processes, due to food-derived molecules interacting with the gastrointestinal epithelial barrier, mucosal immune system and gut microbiota, and induce local and systemic modifications (7).

Evidence also demonstrates that dietary therapy can improve well- being and decrease psychological distress (22).

Despite the benefits demonstrated by current evidence, adverse effects were also observed in some patients during the intervention periods with the anti-inflammatory diet, namely heartburn, stomachache, nausea, and diarrhea, these effects may be caused by increased of some citric fruit, as well by increased of fiber intake compared to previous to the intervention (2, 3, 17, 20).

According to current evidence, the effect of PUFAs explain part of the beneficial effects associated to the anti-inflammatory diet in RA. However, it is worth noticing that the effect of isolated PUFAs (i.e. PUFAs supplementation) differs from the effect of PUFAs inserted in a food source. The anti-inflammatory diet is a food pattern and the combination of different compounds instead of single nutrients presents a synergic effect that can be useful for the nutritional management of RA.

For the implementation of the anti-inflammatory diet, it is important to take into account not only the clinical status of these patients, but also their usual dietary pattern, clinical history, nutritional status, tolerance, and the predisposition to adhere to it, since the greater the adherence, the greater the success of the nutritional intervention. In this way, nutritional education is essential for better intervention.

More high-quality studies investigating the effects of an anti- inflammatory diet on RA are needed, particularly randomized controlled trials. Also, the inclusion of objectively measured outcomes instead of self-reported ones would improve results consistency. Moreover, standardized procedures would allow the comparability of the results from different studies.