INTRODUCTION

The Mediterranean Dietary Pattern (MDP) includes nutritional and sociocultural aspects typical of the countries with Mediterranean features, reflecting their great diversity of cultures and traditions (1). However, some dietary characteristics stand out: i) the predominant consumption of plant-based food, such as vegetables, fruit, whole grain cereals, pulses and nuts; ii) the use of olive oil as the main source of fat; iii) the moderate intake of dairy products, mainly yogurt and cheese; iv) the moderate consumption of fish and eggs; v) the low intake of meat, preferring poultry meat over red meat, which is reserved only for special occasions and vi) the low to moderate wine intake with main meals (2-4). Traditionally, the predominant cooking techniques were stews and soups typically seasoned with olive oil and aromatic herbs (2). In addition, the MDP also includes the choice of fresh and local products that respect seasonality and biodiversity (1, 4, 5), socializing with family and friends during the mealtime and sharing recipes from generation to generation (2, 4).

Currently, it is known that an optimal adherence to the MDP is associated with better control and lower risk of developing different types of chronic and degenerative diseases with a possible effect on the increase of life expectancy and quality of life (6-9). Specifically, among adolescents, a higher level of adherence to the MDP may be related to enhanced quality of life and well-being (10), as well as improved cognitive skills (11) and better academic performance (12). Similarly, there also seems to be an inverse relationship between the adherence to the MDP and body mass index (BMI) (13,14), waist circumference (13), and total body fat (13). Despite all these benefits, over the past few years, MDP has been abandoned by young people in Mediterranean countries (15, 16). On the other hand, a “Western” dietary pattern, richer in saturated fat, refined cereals and processed food (17) has emerged (18-20). This phenomenon is called “Nutrition Transition” and is associated with an increased prevalence of overweight and obesity (2, 20, 21). In Portugal, this trend is also present (22) in children and adolescents, leading to low levels of adherence to the MDP (23, 24), although studies about this subject are still scarce. Moreover, adolescence is a transition stage in which psychological, social and physiological changes of great importance take place. Eating habits acquired during this phase are crucial as they usually persist into adulthood and can have an impact on the individual’s future health (25,26).

Internationally, several studies have been carried out to understand the factors associated with the dietary habits of children and adolescents; yet, in Portugal, this subject remains scarcely developed. It is essential to study the factors associated with MDP adherence among Portuguese adolescents in order to design and develop public health intervention programs that can minimize the impact of “Nutrition Transition” and the associated diseases and maximize the adherence to the MDP, since it is a healthy dietary pattern with proven benefits (27-30). Therefore, this study aimed to analyze the adherence to the MDP and its associated factors in a sample of adolescents from the north of Portugal.

METHODOLOGY

Study design: Cross-sectional study carried out between January and March 2020 in Vila Nova de Gaia, a city located in the north of Portugal. Population and sampling: The study population was composed of adolescents attending the 5th to the 12th school grades from a city located in the north of Portugal. From a total of 14 public school groups (selected by convenience of access), the five which had both primary school and high school were chosen. From these five school groups, the nearest (more urban) and the furthest (more rural) from the coast were selected to obtain a sample as heterogeneous as possible.

Within the schools included, the students’ classes were randomly selected and all the students in these classes (n = 860) were invited to participate. Of these, 240 students accepted to participate on the investigation (participation rate of 27.9%).

A minimum sample size of 141 participants was defined so that with α = 0.05 and β = 0.15 a correlation coefficient of 0.25 or higher would be significant. Of the 240 students who accepted to participate, 33 (13.8%) did not fulfilled the data collection questionnaires, 20 (8.3%) were not Portuguese, one (0.4%) was vegetarian and another was coeliac. Thus, the final sample comprised 185 adolescents aged between 10 and 19 years with Portuguese nationality and without any special educational needs that would prevent them from completing data collection independently and without specific diets (for example, vegetarianism) or diets conditioned by the presence of diseases (such as celiac disease or allergy to cow’s milk protein).

Data collection: Data collection was performed during the school season, from January to March 2020. The personal data of each participant was initially collected, namely, sex, age, weight and height (self-reported), location of the school (coast versus inland), adolescent’s level of education, parent’s level of education, total household monthly income and composition.

Regarding the education of the mother and the father, students had to indicate whether they had completed the 1st cycle of primary school (until 4th grade), 2nd cycle of primary school (until 6th grade), 3rd cycle of primary school (until 9th grade), high school (until 12th grade), Bachelor, Master or Doctorate degree. The “Parents’ education” variable was created by selecting the highest degree of school education completed by both parents.

For household composition, adolescents had to report the number of people living in the same house permanently (including themselves). In relation to the total household monthly income, students had the option to select “< 500€”, “500 to 999€”, “1000 to1999€”, “≥ 2000€” or “Do not know/Do not want to answer”.

Using the reported weight and height data, BMI was calculated using the following formula: [body weight (kg)/height (m) 2]. Then, the BMI percentiles for sex and age (P) were determined according to the World Health Organization (WHO) (31) reference growth curves for children and adolescents aged 5 to19 years. BMI of adolescents was then classified as underweight (P < 3rd), normal weight (P 3rd to 85th), pre obesity (P 85th to 97th) or obesity (P > 97th). Due to the low number of participants, those in the “Underweight” category (n = 2) were excluded and “BMI classification” was divided into 3 groups: “Normal weight”, “Pre-obesity” and “Obesity”.

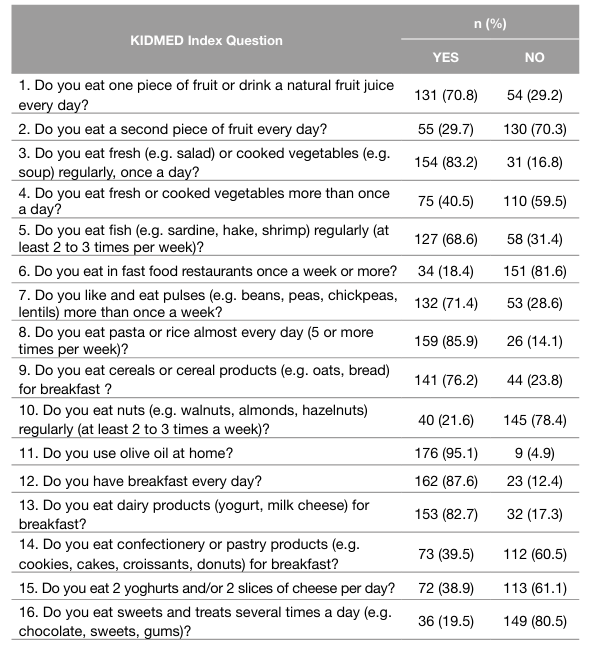

To measure adherence to the MDP, the KIDMED Index was used. A translated and cross culturally adapted version (32,33) derived from the original one developed by Serra-Majem et al. (34) was self-administered to the target population. The KIDMED is an index based on MDP principles consisting of 16 closed-ended questions, with the associated total score ranging from -4 to 12. A positive answer to questions with a negative connotation with MDP adherence (n = 4) are scored -1 point, while questions with a positive connotation (n = 12) are scored +1 point. The sum of the scores for all the questions allows the classification of the adherence to the MDP as low (≤ 3 points), moderate (4 to 7 points) and high/optimal (≥ 8 points). The “Adherence to the MDP” was transformed into a dichotomous variable by combining participants with low and moderate adherence into a single category.

Statistical analysis: Statistical analysis was performed through SPSS® version 26.0 for Windows. The descriptive analysis consisted of calculating the mean and standard deviation (SD) for quantitative variables and the absolute frequencies (n) and percentages (%) for categorical variables. The quantitative variables’ normality was analyzed through the skewness and kurtosis coefficients. Results were considered statistically significant when the significance level (p) was below 0.05.

Fisher’s Exact Test was used for comparing proportions of independent samples. Binary logistic regression was performed to study the predictors of high adherence to the MDP; the 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and the respective Exp(β) were also calculated.

Ethics: The present research work used secondary data from the study “Reproducibility and validity of the Mediterranean Diet Quality Index (KIDMED Index) in a sample of Portuguese adolescents” (32) whose execution was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Ethic Committee from the Institute of Public Health of the University of Porto (number CE19127).

Moreover, authorization from the Portuguese Government’s Education General-Direction through the system of monitoring surveys in the school environment (registration number 0702600001) and from the school groups directors were obtained. Written informed consents from the adolescent’s tutors, as well as authorization from the adolescents themselves were obtained, to rightfully proceed on gathering data. The participants had the right to leave the investigation at any given time, without any need for further explanation.

RESULTS

Sample characterization and adherence to the MDP: The sample consisted of 185 adolescents, mostly female (60%), with an average age of 13.85 (SD = 2.5) years and 38.4% attending the 7th to 9th grade. Regarding the BMI classification, more than half of the sample is classified as normal weight (62.2%). The number of members in the household ranged from 2 to 11, with an average of 4 people. In addition, most of the adolescents (54.5%) belong to a household whose total income is between 500 and 1999€ per month. Furthermore, 23.0% had at least one parent who had completed more than the 12th grade. Regarding MDP adherence, 63.2% of students had low/moderate adherence while 36.8% showed high adherence. The average KIDMED Index Score was 6.8 (SD = 2.0) points. Regarding the features with higher proportion of adherence, most adolescents use olive oil at home (95.1%), eat breakfast every day (87.6%), and eat pasta or rice almost every day (85.9%). On the other hand, most adolescents don’t eat nuts regularly (78.4%), don’t eat a second piece of fruit every day (70.3%), and don’t eat 2 yoghurts and/or 2 slices of cheese per day (61.1%) (Table 1).

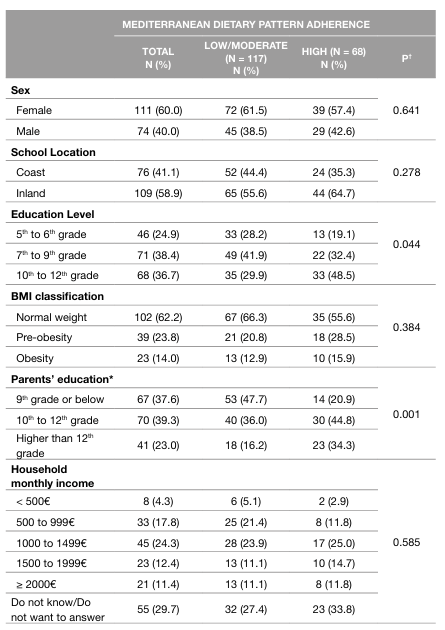

Factors associated with MDP adherence: Higher MDP adherence is associated with the school year attended by the adolescents, with 48.5% of those with high adherence attending the 10th to 12th grades, while only 29.9% of adolescents with low/moderate adherence attended those higher grades (p = 0.044; Table 2). The education level completed by the parents was also related to MDP adherence: 47.7% of adolescents with low/moderate adherence but 20.9% of those with high adherence had parents with the 9th grade or below (p = 0.001; Table 2).

Table 2 Sample characterization, total and according to the level of adherence to the Mediterranean Dietary Pattern (n = 185)

BMI: Body Mass Index

*Highest degree of school education completed by any parent

† Fisher’s exact Test

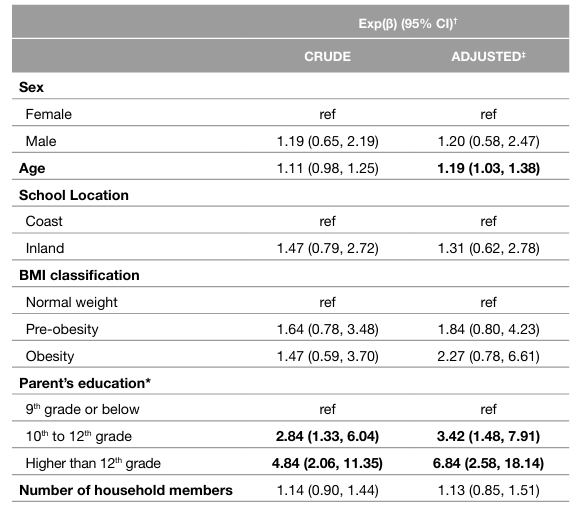

The results obtained by binary logistic regression are presented in Table 3. Regarding the quality of the model, R2N = 0.197 and p = 0.002 were obtained for the adjusted binary logistic regression. Through unadjusted binary logistic regression, it was found that the higher the parent’s educational level, the more likely adolescents are to have a high level of adherence to the MDP. When the model is adjusted, this effect remains statistically significant, revealing that adolescents whose parents completed 10th to 12th grade are 3.42 times more likely to have high adherence to the MDP than those whose parents only finished 9th grade or below. Likewise, students whose parents have completed higher than 12th grade are 6.84 times more likely to demonstrate optimal adherence to the MDP compared with the reference group. Regarding age, in the adjusted model, it was noticed that the older the adolescent, the more likely they are to have high adherence to the MDP (Exp(β) = 1.19; 95% CI = 1.03, 1.38) (Table 3).

Table 3 Factors predicting Mediterranean Dietary Pattern adherence (n = 185)

BMI: Body Mass Index

Exp(β: Exponentiation of the β coefficient

ref: Reference

95% CI: 95% Confidence Interval

*Highest degree of school education completed by any parent

† From binary logistic regression models

‡ Adjusted for all the other variables present in the table.

DISCUSSION OF THE RESULTS

The results of this study highlight the need to improve MDP adherence among adolescents from north of Portugal, since only 36.8% can be classified as having high adherence. These results are in line with others obtained in the north of Portugal, where 42.1% and 40.8% of the adolescents showed high adherence to MDP (24,35). Interestingly, a study carried out in a sample aged between 11 and 16 years from Algarve reports a much higher level of adherence with 52.5% of adolescents showing high adherence and only 5.4% having a low adherence (36).

The need to improve adherence to the MDP of adolescents crosses several Mediterranean countries. In Spain, the high adherence ranges from 30.9% in the south of the country (37) and 26% in the Catalonia region (38). In northern Italy, only 19.6% of adolescents have high adherence to the MDP (39), while in the south this value is even lower, standing at 9.1% (13). In Greece, the high level of MDP adherence among young people ranges from 8.3% (14) to 21% (40).

Adolescents are moving away from MDP by reducing their consumption of fruits, vegetables, pulses and fish (41,42), and increasing the intake of “fast food”, sweets and soft drinks (15), which confirms the occurrence of “Nutrition Transition” (43). The results of the KIDMED Index reinforce this premise since 39.5% of the adolescents consume pastry and confectionery products for breakfast and only 29.7% eat a second piece of fruit every day; similarly, only 40.5% report eating vegetables more than once a day. Although 87.6% of the participants eat breakfast every day, data from a WHO report shows that adolescents’ daily breakfast intake has been decreasing, with Portugal having the largest decline among 13-year-old girls compared to data from 2014 (26). This data reflects the need to promote the MDP among children and adolescents, as it is at this stage of life that the dietary habits prevailing during adulthood are created and can influence the development of several chronic diseases (26).

In this study, it was found that adolescents whose parents completed a higher level of education were more likely to have a better level of adherence to the MDP. Several authors confirm the association between parents’ education and a better quality of diet, related to a high level of adherence to the MDP (14, 44). The basis of this association is thought to be the fact that a higher education level of parents means a higher socioeconomic level and, therefore, more financial availability to buy healthy food (14, 42). This idea is supported by the study conducted by Alburquerque et al. which shows that increased MDP adherence is associated with a higher dietary cost (23). Higher education of parents can also lead to deeper knowledge about food and nutrition, which promotes the adherence to a healthier dietary pattern (45). In this study, MDP adherence is not associated with the total household monthly income, probably due to the low response rate to this item. However, it is described that one of the main determinants of the degree of adherence to the MDP is the socioeconomic level (46). Reflecting on this issue, it is clear that reducing educational and economic inequalities could have a positive impact on the adoption of healthier eating habits (26).

Concerning age, in contrast with our findings, some studies pointed to a decrease in adherence as age increases (24,47). However, this association is not always clear since a systematic review (48) does not support the hypothesis that MDP adherence varies considerably with age. In the present study, older adolescents were more likely to have high MDP adherence than younger adolescents. Similar results were reported in the study by Archero et al. where primary school children were found to make unhealthier food choices, resulting in lower adherence to the MDP (39).

According to the present study, sex, school group location, BMI and number of household members are not related to MDP adherence. Regarding the influence of sex on the level of MDP adherence, scientific evidence showed no significant differences in adolescence (16, 47, 49), except in one study conducted on a representative sample of the young Greek population, in which female adolescents had higher adherence to the MDP (14). Although our results do not establish an association between MDP adherence and BMI classification, Mistretta et al. reported that good MDP adherence was associated with a 29% decrease in the possibility of adolescents being overweight or obese (13). On the other hand, a systematic review (6) emphasizes that this relationship is not consistent for this age group. The results presented in our study may be affected by the fact that weight and height are self-reported since there is a trend to underestimate weight (50, 51) and overestimate height, which will affect the accuracy of BMI classification (51). In addition, self-reporting of weight and height in younger adolescents may also potentially add great errors in BMI classification. Concerning the school groups’ locations, the closest to the coast is situated in a more urban area and the furthest in a more rural area. Thus, it would be expected that in more rural areas the MDP adherence would be higher as described in the literature (42, 52). Contrary to expectation, this association did not achieve statistical significance, possibly because the schools considered more rural are still a part of a city that is mainly an urban environment.

Strength and limitations: This research work has some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. Its cross-sectional design does not allow the establishment of causal relationships. Also, anthropometric data were self-reported, which may cause problems, specifically in younger adolescents. The main strengths of this study are the fact that KIDMED Index was self-administered, avoiding interviewer bias. Moreover, the version of KIDMED Index applied was previously translated and adapted to the target population and the sample was as heterogeneous as possible including students from two school groups with different characteristics, adolescents of different school years (5th to 12th) and ages (10 to 19 years old). Finally, it should be noted that studies on MDP adherence among Portuguese adolescents are still scarce. Thus, the main contribution of this research work is that it generates hypotheses about this subject that can be used as the baseline for future investigation.

CONCLUSIONS

Taking into account the high proportion of adolescents with low/ moderate adherence to the MDP, it is crucial to design and implement public health intervention programs in order to maximize their adherence to a healthier dietary pattern. This study identifies the groups that could benefit the most from these intervention programs that enhance MDP adherence, in this case, the younger adolescents and those whose parents have a lower level of education. Reflecting on the role of parents in the acquisition of healthy lifestyles, it would be important and beneficial for them to participate in these intervention programs, especially for those with a lower educational level.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

IJ: Participated in the formulation of the research question, designing the study, data analysis, interpreting the findings and writing the manuscript; RP: Participated in data analysis, interpreting the findings and in the reviewing process; MR: Participated in the formulation of the research question, designing the study, generating and gathering the data and in the reviewing process; and SR: Participated in the formulation of the research question, designing the study, interpreting the findings and in the reviewing process. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.