INTRODUCTION

Palliative Care (PC) is the active, coordinated, and holistic care of individuals across all ages with serious health related suffering due to severe illness, and especially of those near the end of life. It aims to improve the quality of life of patients, their families, and caregivers. It is a care that includes prevention, early identification, comprehensive assessment, and management of physical issues, including pain and other distressing symptoms, psychological and spiritual distress, and social needs. It provides support to help patients live as fully as possible until death by facilitating effective communication, helping patients and their families determine goals of care (1). PC is applicable throughout the course of an illness, according to the patients´ needs and intends neither to hasten nor postpone death. It affirms life and recognizes dying as a natural process. It provides support to the family and the caregivers during the patient’s illness, and in their own bereavement. PC is delivered recognizing and respecting the cultural values and beliefs of the patient and the family and it is applicable throughout all health care settings and in all levels. PC also requires specialist PC with a multiprofessional team for referral of complex cases (1). According to some authors the nutrition of the PC patients is usually altered so eating-related distress arises in all life limiting diseases sooner or later. It is highly recommended the inclusion of dietitians/nutritionists as members of the PC teams or at least that they work closely with the team to give the best and the most comprehensive and holistic nutritional care to patients as food and nutrition issues contribute to patients’ total pain (2-46). From the literature consulted, dietitians/nutritionists´ roles in PC have been poorly investigated. However, more recently it seems they have been given more attention. Thus, dietitians/nutritionists develop their jobs with more scientific, technical rigour and from a clinical and ethical point of view it is necessary that they develop and define properly their professional competences in PC (2, 14-29).

OBJETIVES

To identify a set of professional competences of dietitians/nutritionists in the field of PC.

METHODOLOGY

A systematic literature review, adapted from the PRISMA methodology, was conducted. The identification of publications was initiated through searches in the databases Pubmed, CINAHL, Academic Search Complete, and Web of Science. The keywords used were “nutrition” and “palliative care”. By convenience a complementary manual search of publications that did not emerge in previous search was added. Working documents and guidelines from professional associations and working groups in nutrition and PC fields were also searched. Regarding the exclusion criteria, the following types of publications were defined: letter to the editor, comments, editorials, and case studies. The selection of publications presumed, at least, one of the following inclusion criteria: the publication includes core competences in the area of PC; the publication specifically refers to the dietitian/nutritionist competences in PC; the publication describes nutritional interventions in the area of PC in a cross-sectional perspective, including oral feeding, artificial nutrition, assessment of nutritional status, meanings of food, emerging ethical issues; the publication indicates interventions of the nutritional forefield in the area of nutritional support related to PC. The selection process of publications was initiated by reading of the title and abstract, after which, in the selected publications, the document was completely read and subsequently the competences were extracted. A total of 7472 potentially relevant publications were identified initially through research in the databases mentioned above. In addition, to complement the research carried out, 13 more references were included through manual search, relevant to the theme that was intended to be investigated and met the criteria previously defined. Thus, a total of 7485 publications were analysed, excluding 4 publications because they were duplicated. Based on the reading of the title and abstract, 7379 of these publications were excluded, because they did not address the theme that was intended to investigate. Thus, 106 publications initially appeared to meet the selection criteria. However, after their full reading, 32 met at least one of the previously established inclusion criteria. For rejected publications, the justifications are: articles directed only to the nursing area (n=17), articles directed only to the medical area (n=14), brief reference to nutrition (n=8), german language (n=4), nutrition and palliative sedation (n=4), prevalence and impact of artificial nutrition (n=4), home PC with brief reference to nutrition (n=3), parental perceptions (n=3), perceptions of health professionals (n=3), paediatric PC (n=3), neonatal PC (n=2), nutrition for cognitive improvement (n=2), emotional impact of eating on health professionals (n=2), survival and quality of life (n=1), parenteral nutrition (n=1), editorial (n=1), and hastening death (n=1).

RESULTS

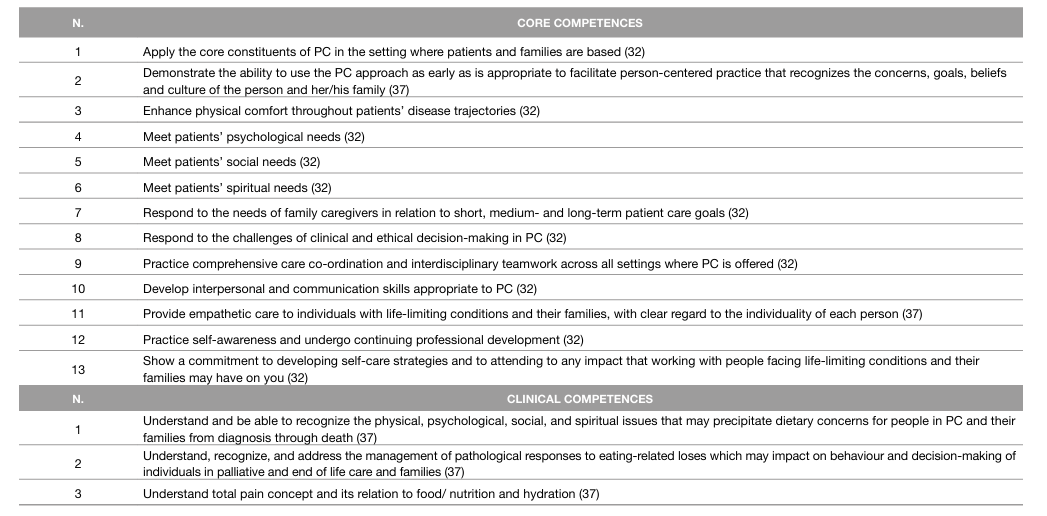

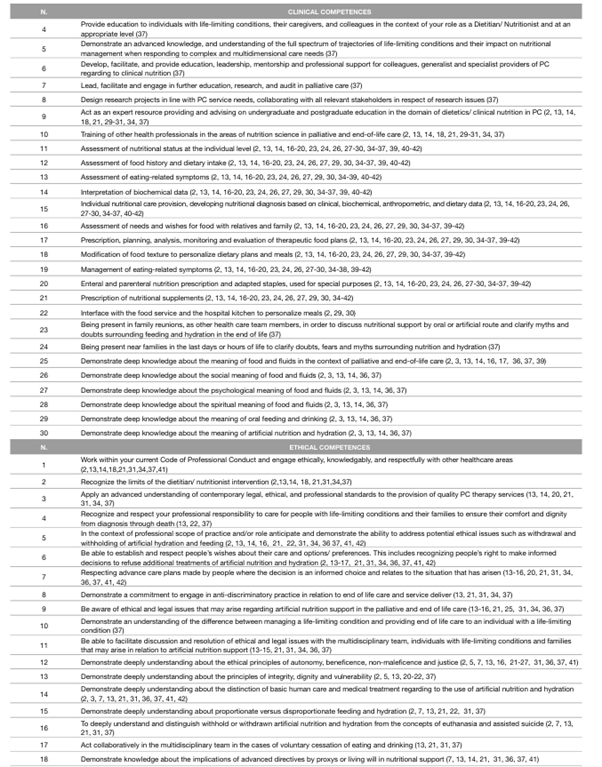

From the set of publications were found: 18 literature reviews (2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, 16, 17, 22-27, 33, 35-37, 41), 3 original articles (15, 19, 30), 2 book chapters (13, 18), 2 position statement (21, 31), 1 guideline article (34), 2 professional articles (29, 42), 2 books (20, 39), 1 white paper (32), and 1 taskforce document (37). After being identified the competences were written and grouped in three dominions according to the area they were associated with: the core competences mainly defined by the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) (32) and by the PC Competence Framework Steering Group of Dublin (37); the clinical competences regarding the area of clinical nutrition; and the ethical competences where all the subjects related to ethical issues were included. After the organisation and writing of competences in these dominions, the results were: 13 core competences, 30 clinical competences, and 18 ethical competences (Table 1).

DISCUSSION OF THE RESULTS

Core Competences

Some authors state that to work in PC, dietitians/nutritionists must have a combination of multiple attributes, including aptitude and technical competence which allows them to comply with philosophy and principles of PC and understand the total pain (32, 36). The empathy, interest in PC, the willing to work in this area within a multidisciplinary context and a good communication capacity were also allocated as essential personal characteristics to work in such a complex area of human care as long as taking care and cope with themselves because of their contact with complex and emotional clinical cases (30, 32, 37).

Clinical Competences

The following competences were identified: nutritional assessment, diagnosis, intervention, and monitoring. However, the first fundamental clinical competence is the ability to understand the food phenomenon as multidimensional and a part in the total pain concept, recognizing food has a social, cultural, emotional, religious, and spiritual meaning, and changes during the trajectory of the disease can be a factor of eating--related distress for patients, family members and caregivers. It is their competence to assess unique dietary needs for each patient considering the social determinants of health, ethnicity, culture, gender, sexual orientation, language, religion, age, and their respective preferences. Also in this context, the dietitians/nutritionists assess the patients and family members/carers capacities and needs in relation to food education for specific purposes with dietitians/nutritionists as a source of credible information (2, 3, 13, 14, 16-21, 28-31, 36,37, 41-43).

The literature states that it is the dietitians/nutritionists’ responsibility to define objectives and to establish realistic nutritional goals and treatment plans, making appropriate adjustments in the nutrition care process, collaborating in the discharge plans, establishing comfort feeding, or prescribing oral nutritional supplements or artificial nutrition, when appropriate (21, 29, 30, 37). It is also pointed out as a competence the advice on ways of preparation, supplementation, and flexibilization of food routine and previous dietary restrictions (36). Another clinical competence is the articulation with the hospital kitchen. Thus, regarding the area of cooking and distribution of meals, dietitians/ nutritionists can modify eating routines and schedules where meals can be customized appropriately (29, 30).

Dietitians/nutritionists also have as competences the participation and promotion of research and audit within the service (29, 30, 37). Also in the training aspect, dietitians/nutritionists are capable to train colleagues in the nutrition service as well as other health professionals (29, 30, 37). Within the last hours and days of life, dietitians/nutritionists have as specific clinical competence the ability to support the wishes of patients and clarify any doubts and myths regarding nutrition in the end-of-life and agonic phase that family members and caregivers may have (37).

Ethical Competences

The literature points out that dietitians/nutritionists who deal with PC patients and family members have skills at a level of patient-centered care adding the ethical dimension to their clinical nutrition practice and applying the principles of autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, justice, integrity, vulnerability and dignity according to patients’ proxys, values, religion, spirituality, and culture perspective of their own quality of life and goals (2, 5, 7, 13-15, 31, 32, 34, 37, 41).

Dietitians/nutritionists have the competence to work respecting their code of ethics and considering the limits of their intervention and respect for the other professional areas of the multidisiciplinary team. In addition, they should be able to define and at the same time respect the wishes of the patient related to food choices and preferences, and in this context, they should recognise the importance of properly informed consent and decision-making (2, 5, 37).

Dietitians/nutritionists have the duty to protect life so they must participate and collaborate in the ethical deliberation process of issues related to food and nutrition support (31). As ethical competences, they must develop several essential dimensions: the dimension of knowledge in the area of clinical nutrition, moral reasoning, legislation, involving possible emerging ethical issues, religious, and cultural values, to the policies of the institution where PC takes place; the dimension of practical knowledge: the analysis and evaluation of the ethical issues, critical thinking, ability to negotiate and to communicate, being a facilitator of ethical discussion and deliberation and ethical decision-making capacity; the dimension of attitudes: empathy, patient, ability to approach the team, to comfort despite the uncertainty of clinical situations and comfort despite possible negative feelings of the patient and family members regarding to the dietitian as an healthcare professional; the virtues dimension: integrity, respect and compassion (21, 31).Other authors also state that dietitians/nutritionists have a responsible and active role in ethics deliberation of issues related to voluntary cessation of eating and drinking and with issues surrounding the withholding and withdrawing of artificial nutrition and hydration (21, 31, 32, 34, 37, 41). Some authors also affirm that dietitians/nutritionists have a fundamental role not only in promoting the use of advanced directives and referring patients to a competent professional area to elaborate them (37).

Limitations

The fact that a blind evaluation methodology was not used by more than one reviewer of the publications to be included in this review and in the identification of competences could represent a limitation, because this would allow a more accurate assessment, limiting the investigators’ biases. The review was not carried out in all existing databases and languages may also have interfered with the results of this review, as other relevant articles could possibly have been found. It is also important to highlight the difficulties experienced in the process of systematic literature review. These difficulties consisted of the scarcity of publications that addressed, identified, and described exclusively professional roles and competences of nutritionists/dietitians in PC. In addition, the fragmentation and poor development of this theme among the literature was also a limitation.

CONCLUSIONS

Although the nutrition care process is a responsibility from many healthcare professionals, it is only enhanced through the action of dietitians/nutritionists since they are the professionals who aggregate knowledge and expand the technical competence of nutritional care and support offered by the multidisciplinary team. An interesting future research would consist in submitting the competences found to an expert panel of nutritionists/dietitians and obtaining consensus about this issue by the Delphi Method.